Abstract

Study Objective

To examine adolescent and young adults’ priorities, values and preferences affecting the choice to use intrauterine contraception (IUC).

Design and participants

Qualitative exploratory semi-structured interviews with 27 females 16–25 years old on the day of their IUC insertion. Analysis was done using a modified grounded theory approach.

Setting

Outpatient adolescent medicine clinic located within an academic children’s hospital in the Bronx, New York

Results

We identified four broad factors affecting choice: (1) personal, (2) IUC device-specific, (3) health care provider (HCP), and (4) social network. The majority of the participants perceived an ease with a user-independent method and were attracted by the IUC’s high efficacy, potential longevity of use and the option to remove the device prior to its’ expiration. Participants described their HCP as being the most influential individual during the IUC decision-process via provision of reliable, accurate contraceptive information and demonstration of an actual device. Of all people in their social network, mothers played the biggest role.

Conclusions

Adolescents and young women choosing IUC appear to value IUCs’ efficacy and convenience, their relationship with and elements of clinicians’ contraceptive counseling, and their mother’s support. Our results suggest that during IUC counseling, clinicians should discuss these device-specific benefits, elicit patient questions and concerns, and use visual aids including the device itself. Incorporating the factors we found most salient into routine IUC counseling may increase the number of adolescents and young women who choose IUC as a good fit for them.

Keywords: adolescent, contraception, contraception decision making, counseling, decision making, female, Intrauterine Devices, qualitative research, reproductive health

Introduction

Although the United States (U.S.) adolescent pregnancy rate is decreasing overall,1 the U.S. rate is still among the highest in the developed world.2 Annually over half a million U.S. 15–19 year olds become pregnant.3 More than 80% of adolescent pregnancies are unplanned.4 Issues around contraception access and utilization contribute to the unplanned pregnancy rate. Recent studies have found that the use of highly effective contraceptives such as intrauterine contraception (IUC) can decrease adolescent unplanned pregnancy.5–7 Although current professional guidelines recommend IUC as a potential first line contraceptive for adolescents 8–10 only 5% of contracepting U.S. women aged 15–24 use IUC.11

Adolescents and young women select a contraceptive based upon their priorities, values and preferences.12,13 Understanding what an individual may value or prefer in regards to specific contraceptives can help clinicians tailor their contraceptive counseling and support informed contraception choice. Several studies have examined adolescents’ knowledge, beliefs, and interest in IUC from the perspective of non-IUC users.14–17 There is limited data about the experiences of adolescents or young women who actually use IUC. In a qualitative study out of St Louis, adolescents and young women who were relatively new IUC users reported that they chose IUC because of the device’s effectiveness, potential long duration of use and convenience.18 Brown et. al interviewed adolescents one to 24 months after initiating IUC in order to examine their IUC adoption process. When weighing whether to choose IUC, these adolescents described a process of IUC awareness, reaction, information gathering, adoption and adjustment in which the clinician played a significant role.19 In another study, post-partum adolescent IUC users said that supportive clinicians or family members as well as perceived reproductive autonomy facilitated their IUC use.20 We found no published studies involving adolescents and young adults conducted contemporaneously with their initiation of IUC use. Exploring factors affecting IUC choice concurrent with method initiation reduces recall bias and thus results in a more accurate description of the most salient factors influencing choice. Therefore we designed an exploratory qualitative interview study with adolescents and young women on the day of their scheduled IUC insertion. Our objective was to examine their priorities, values, preferences and key factors affecting the choice to use IUC. We were specifically interested in elucidating factors that could potentially improve IUC counseling.

Materials and Methods

This study was approved by the Albert Einstein College of Medicine Institutional Review Board.

Setting

We recruited females 16 years and older who had an IUC insertion appointment at an outpatient adolescent medicine clinic located within an academic children’s hospital in the Bronx, New York. The adolescent medicine clinic has an IUC insertion service which is staffed by AJ (last author), an adolescent medicine specialist. Patients do not need a referral to attend this clinic, nor do they need to be a patient within the hospital system. However, most patients who access the adolescent clinic for IUC insertion are either referred from a provider within the hospital system or by a friend who had an IUC inserted in the clinic. Seventy percent of the patients who schedule an IUC insertion appointment arrive for their appointment.

Recruitment

Potential participants were approached by a research assistant after checking in for their appointment but before they saw the clinician for counseling and device insertion. If the patient expressed interest in participating in the study, she was taken to a private room to discuss the project in more detail. If she agreed to participate, an IRB approved oral informed consent script was read; the participant gave oral consent. There was no incentive for participation.

Interview guide

Since little is known about our topic, SER (first author) and AJ designed an exploratory qualitative interview study 21. SER and AJ developed an interview guide informed by the existing literature and in consultation with experts in the field. The guide included open-ended questions with probes covering the following broad categories: Contraceptive experience; Contraceptive priorities; Reason for selecting IUC now; Interaction with clinician; Social networks’ influence; Knowledge of female reproductive anatomy, Knowledge of IUC mechanism of action; and Pregnancy desires.

Data collection

SER, is an experienced qualitative researcher. She trained FK and MF (authors) in interview technique. Willing participants were consented and interviewed by either FK or MF in a private space. Interviews were conducted in English, lasted 15–25 minutes, were recorded and later transcribed. SER and FK reviewed interviews as they were completed and initially made minor refinements to the interview guide 22. To supplement our qualitative data, we extracted de-identified electronic medical record data routinely collected during the IUC insertion visit including participant’s demographics, pregnancy and contraception use history.

Data analysis

Thematic analysis and coding scheme development

We employed a modified grounded theory analysis approach overall 21. Using an iterative process of analysis starting with initiation of data collection, SER and FK reviewed transcripts within a week of data collection to assess the interview guide’s effectiveness, identify emerging themes, develop a preliminary explanatory model and assess for saturation. We interviewed until reaching saturation. SER and MF (first author) conducted final analysis via independently reading every transcript, identifying themes, reviewing transcripts excerpt by excerpt to refine a coding template, and developing an explicit codebook.

Achieving reliability

After completing the codebook, SER and MF independently coded all the data and worked together until reaching conceptual coherence of the coding attributes. AJ (second author) coded a sub-set of the data and was consulted when SER and MF had discordant results. An explicit effort was made to search for disconfirming cases. Transcripts were entered in Dedoose qualitative software (www.dedoose.com) and codes applied.

Results

During the 13 clinical sessions that interviews were conducted (spanning July 2013-July 2014), 36 patients presented for IUD insertions. Because of clinic flow issues, we were only able to invite 27 patients to be interviewed. All 27 agreed to be interviewed and completed their interview.

Prior to their insertion appointment, nine participants received contraceptive counseling with AJ (last author), eight with other adolescent medicine providers, and 10 were referred from other general pediatric providers. For those 10, their IUC insertion appointment was their first contact with the adolescent medicine clinic.

Participants’ median age was 19 years, 56% were Latina, 22% had ever been pregnant, and 67% had Medicaid insurance. All but one of our 27 participants had used at least one contraceptive method prior to the IUD. Most had tried multiple methods. The most common prior methods were condoms (92%), followed by the oral contraception (58%). The one participant who had never used contraception had never been sexually active. She wanted an IUD to treat dysmenorrhea. Twenty-two percent of participants had a chronic medical condition that limited their contraceptive options or made pregnancy high risk. Nineteen percent chose the IUD primarily to reduce menstrual bleeding. Seven of the 27 participants who intended to get the IUD at the time of the interview did not have an IUD inserted that day. These seven participants are included in our analysis because at the time of their interview they intended to have an IUD inserted, and so discussed their decision-making process. Demographic characteristics as well as reasons for not having the IUD inserted are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of adolescents and young adults interviewed

| Number of participants (N=27) | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (median, range) | 19 | (16–25) |

| Latina | 15 | 56% |

| Has Medicaid insurance | 18 | 67% |

| Current Student | 25 | 93% |

| Ever Pregnant | 6 | 22% |

| If ever pregnant, pregnancy outcome: | ||

| Singleton birth | 1 | 17% |

| Twin birth | 2 | 33% |

| Abortion/miscarriage | 3 | 50% |

| Used contraception at last intercourse | 23 | 85% |

| Ever used contraception prior | 26 | 96% |

| If ever used contraceptives, type:* | ||

| Condom | 24 | 92% |

| Oral contraceptive | 15 | 58% |

| Medoxyprogesterone injection | 7 | 27% |

| Vaginal ring | 4 | 15% |

| Transdermal patch | 3 | 12% |

| IUD, prior | 2 | 8% |

| Emergency Contraception | 2 | 8% |

| History of chronic medical condition with some contraceptive contraindications or making pregnancy high risk | 6 | 22% |

| If has chronic medical condition, type:* | ||

| Diabetes | 3 | 38% |

| Lupus | 1 | 13% |

| Coagulopathy | 1 | 13% |

| Migraine with aura | 1 | 13% |

| Kidney disease | 1 | 13% |

| Scleroderma | 1 | 13% |

| Selecting IUD primarily for control of menorrhagia | 5 | 19% |

| IUD Inserted on day of study interview | 20 | 74% |

| If IUD inserted, type: | ||

| Levonorgestrel | 18 | 90% |

| Copper | 2 | 10% |

| If IUD not inserted, reason: | ||

| Adolescent changed her mind | 2 | 28% |

| Insertion attempted, failed | 2 | 28% |

| Selected Implantable instead | 1 | 14% |

| PID diagnosis within prior three months** | 1 | 14% |

| Pregnant | 1 | 14% |

Some respondents have used more than one contraceptive prior and/or have more than one chronic disease. No respondent ever used implantable contraception.

Per CDC MEC recommendations, current PID diagnosis is contraindication to IUD insertion

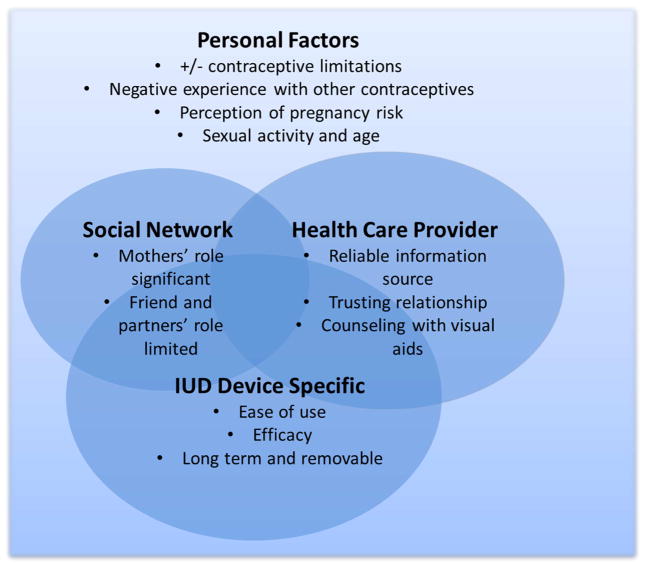

During our analytic process, we identified four broad factors affecting our participant’s choice for IUC. These factors do not comprise a theoretical framework, but rather represent the set of factors that affected our respondent’s decision process: Personal, Device-Specific, Health Care Provider, and Social Network factors. To differing degrees, our respondents value components of all these factors during their decision making process. As depicted in Figure 1, the factors overlap; they do not function in isolation. Below we describe each factor in more detail.

Figure 1.

Factors affecting adolescent and young adult’s choice to use intrauterine contraception

Personal Factors

Personal factors include characteristics about the patient herself including her medical history, contraceptive experiences, perception of pregnancy risk and age. Among all our factors, personal factors have the greatest overlap with the others.

Participants fell into two broad groups based on medical history; those who had a chronic disease which either limits their contraceptive options or makes pregnancy high risk (N= 6), and those who did not (N=21). Other than this difference in contraception options or pregnancy risk, the two groups did not appear to differ in any substantive way in the factors they valued during their IUC decision-making process.

Regardless of their medical history, virtually all participants described negative experiences with side effects of or adherence issues with other contraceptives. Eleven participants had already tried three or more contraceptive methods. Even those who tried numerous contraceptive methods were optimistic that IUC would be a good fit for them. One 20 year-old participant, who has used five other types of contraception, stated: “I have broken down every [contraceptive] option I had and I feel like I’m only left with the IUD so I’m just hoping it works.” Interviewer: “Are you thinking this is your last resort or is something you actually…?” Participant: “No I really want [the IUD] and I feel like it is my best option.”

Increased sexual activity was cited by five participants as a reason for choosing IUC now. “I had sex before, but it wasn’t all the time. I did not have a [regular] sexual partner. So now that I have a boyfriend I think I should [get IUC].”

Some participants alluded non-specifically that IUC was not appropriate for them as a younger teen. For example, one participant specifically said that when she was younger the idea of having a device in her uterus for five years was a deterrent.

IUC Device-Specific Factors

The ease or “low-maintenance” of a user-independent method was valued by 19 participants. This ease is juxtaposed with their past contraception challenges such as remembering to take pills consistently. “… [IUC is] just an easier thing to do. You don’t have to worry about [contraception] every month, or two weeks, or every day…sometimes you forget things. [IUC is] just the easiest way.”

Ten participants cited the high effectiveness of IUC. The phrase “most effective” method was used by a number of participants to describe the primary reason for selecting IUC. For many, this high efficacy alleviated “worry” about unintended pregnancy.

Participants also appreciated both the potential long term use of IUC as well as knowing that there is an option to remove the IUC prior to device expiration. “[With an IUC] you don’t have to worry about things for the next five years. If you want to get pregnant [before the five years are done], then all you have to do is just come and they’ll remove it.”

Health Care Provider Factors

For 11 participants their health care provider (HCP) was cited as the most influential individual during their decision-process around IUC. Over half said that their HCP was the most reliable source from which to get contraception information. Their HCP was described as providing accurate contraceptive information and as being a source of support throughout the decision-making process.

Six participants explicitly described the importance of a trusting relationship with their HCP. The quality of this relationship appeared to be an essential factor in participants’ feeling as though they received comprehensive contraception counseling as well as IUC specific counseling. Participants said their HCP described IUC risks and benefits and processed negative comments participants had heard. Thus participants felt they were making an informed contraception decision. “[My doctor is] very open, she’s real, she doesn’t hold anything back…there are pros and cons to [IUC], obviously more pros cause that’s why I’m choosing it. She was very informative…I like how she was honest with me, which is what I need. I want honest, reliable information.”

As well, participants appreciated HCPs’ use of visual aids to demonstrate the IUC size, placement, and step-by-step information about the insertion process. “What I liked about [IUC counseling] was that [the HCP] drew a little demonstration. She showed with an actual model of your uterus, she showed me what the IUC looked like. Before she was explaining it seemed like [IUC] was bigger. It was good to see the visual because it’s smaller and I see how they are going to do it. I was a little scared about getting it first, that made it easier.” A number of participants were surprised by the small size of the device, and said that knowing the size alleviated some concern about the insertion process.

A minority of participants described unsupportive HCPs. For example, two participants were told by a previous HCP that they could not have IUC due to their age and/or nuliparity

Social Network Factors

Although social network factors were the least influential of the four factors we identified, mothers played a significant role for many participants. Almost half of participants felt particularly supported by their mothers in choosing IUC. “… [my mother] has been there with me 100%. She’s been really helpful and I feel like I wouldn’t be here doing this if it wasn’t for her motivation and her support. Which is what, I think, every girl needs in this time.”

In contrast, friends and partners had limited influence. Very few consulted with their friends when considering IUC. If friends were consulted, and if someone in their friendship group had an opinion about IUC, that opinion was overwhelmingly negative. Over half mentioned their consideration of IUC to their sexual partner. While virtually all partners were described as generally supportive of the decision none explicitly influenced the decision process.

When asked about the role of the internet and commercials, eight participants gave vague answers about looking for IUC information on the internet. Only two cited a specific informational website. Eleven remembered seeing an IUC commercial or lawsuit ad which mentioned possible negative side effects of IUC. While most were not influenced by the commercial, if they had concerns, participants felt reassured after discussion with their HCP. One said that she thought that she was too young to get IUC a few years prior because the actress in an IUC commercial was older.

Discussion

This exploratory study examining salient factors affecting the decision-making process around IUC use is the first conducted with adolescents and young adults on the day of their scheduled IUC insertion. We found that personal factors such as medical history, contraceptive experience and perception of pregnancy risk played a role. As well, participants valued IUCs’ efficacy, duration and perceived ease of use, their relationship with and elements of contraceptive counseling from their HCP, and their mother’s support. Our results suggest that during contraceptive counseling about IUCs, clinician discussion of these device-specific benefits, eliciting patient questions or concerns, and using visual demonstrations of the insertion process, may help an adolescent assess whether an IUC would be a good fit for her.

Our study is one of few to describe perceived device-specific benefits and elucidate important components of the patient-HCP relationship and counseling in a group of adolescents actually initiating IUC use. IUC aspects cited as of value to our participants-- “low maintenance”, high efficacy, longevity, and possibility for device removal prior to expiration, are similar to those reported in studies of adolescent and young women’s perceptions of and theoretical interest in IUC 14–16 as well as a study of actual users.18 Our finding that respondents consider their HCP to be an important source of contraception information and influential during the IUC decision-making process is also consistent with the literature. Adolescent IUC users in California, reflecting back on their choice to use IUC, said that the relationship with their HCP played a crucial role in addressing their questions and concerns, especially concerns based on negative comments from friends.19 Participants in our study similarly were able to process friends’ negative comments when speaking with their HCP. As the California adolescents also described,19 many of our participants valued visual demonstrations during contraceptive counseling. To enhance IUC counseling, clinicians may consider demonstrating the device size and/or use a model to stimulate the insertion process in addition to eliciting patient questions and concerns.

While it appears that social networks are important for many adolescents when choosing a contraceptive in general,23,24 there is limited information about the influence of the social network when considering IUC specifically. Similar to our findings, limited partner influence and mother’s prominent role has been reported in studies of IUC choice.20,25 In contrast to the findings of some others,24,26 social network beyond the mother appeared to have limited influence on our participants’ decision process. This could be a reflection of our participants’ relationship with their HCP in relation to their social network.

Our exploratory study has a number of limitations. We interviewed adolescents at one clinic in an urban tertiary care hospital. This results in an atypically high proportion of participants with chronic disease. Adolescents with limited contraception choices based on their medical history and/or for whom pregnancy could be higher risk may chose IUC for reasons that differ from other adolescents. In addition we had a high proportion of participants who identify as Latina. Another consideration is that one provider, AJ, performed all of the insertions and nine participants met with her prior to their insertion appointment. This raises concern for this being a case study. However, most of the participants initially heard about IUC and were referred for insertion from another provider. They had not yet met AJ until after the interview. Thus AJ had no direct influence on interview responses from the majority of participants. Lastly, since we interviewed adolescents who were presenting for IUC insertion, we do not know in what way their perception about the device itself, their relationships with their HCP and/or their social network differ from those adolescents who knew of but did not choose IUC. Nor do we know how their perception differs from those women who scheduled IUC insertion but did not arrive for their insertion visit.

Despite these limitations, our results add to the literature and suggest patient-defined factors to consider during IUC counseling. When selecting a contraceptive, connecting adolescents’ contraception preferences and values with method characteristics is important. Our participants described their HCPs’ critical role during the decision making process, particularly their trust that their HCP provided the most reliable and accurate contraceptive information. For those adolescents who valued a highly effective contraceptive method, IUCs’ efficacy particularly resonated. We suggest that during IUC counseling, in addition to discussing risks and benefits, HPCs use graphics or visual demonstrations including showing an actual IUC. In addition, clinicians should elicit open conversations about adolescents’ concerns and ask what patients may have heard from their friends regarding IUC. Incorporating the factors we found most salient into routine IUC counseling with adolescents may increase the number of adolescents who make an informed preference that IUC is a good fit for them.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: Dr. Rubin’s research is supported by NIH NICHD grant K23HD067247-01 (Rubin). The NIH had no role in study design; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; the writing of the report; nor the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Disclaimers and/or conflict of interest: none

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Susan E. Rubin, Department of Family and Social Medicine, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY.

Marisa Felsher, Columbia University, Mailman School of Public Health, New York, NY.

Faye Korich, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY.

Amanda M. Jacobs, The Children’s Hospital at Montefiore, Bronx, NY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- 1.Stewart A, Kaye K. Freeze Frame 2012: A Snapshot of America’s Teens. Washington, DC: National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.McKay A, Barrett M. Trends in teen pregnancy rates from 1996–2006: A comparison of Canada, Sweden, USA and England/Wales. Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality. 2010;19:43–52. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kost K, Henshaw S. US Teenage Pregnancies, Births and Abortions, 2010: National and State Trends by Age, Race and Ethnicity. Guttmacher Institute; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finer LB, Zolna MR. Unintended pregnancy in the United States: incidence and disparities, 2006. Contraception. 2011;84:478–85. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2011.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Winner B, Peipert JF, Zhao Q, et al. Effectiveness of Long-Acting Reversible Contraception. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;366:1998–2007. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Secura GM, Madden T, McNicholas C, et al. Provision of No-Cost, Long-Acting Contraception and Teenage Pregnancy. New England Journal of Medicine. 2014;371:1316–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1400506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ricketts S, Klingler G, Schwalberg R. Game Change in Colorado: Widespread Use Of Long-Acting Reversible Contraceptives and Rapid Decline in Births Among Young, Low-Income Women. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2014;46:125–32. doi: 10.1363/46e1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Committee on Adolescence. Contraception for Adolescents. Pediatrics. 2014;134:e1244–e56. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Committee on Adolescent Health Care Long-Acting Reversible Contraception Working Group. TACoO, Gynecologists Committee opinion no 539: adolescents and long-acting reversible contraception: implants and intrauterine devices. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2012;120:983–8. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182723b7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sexual and Reproductive Health Care: A Position Paper of the Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine. J Adolesc Health. 2014;54:491–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Branum AM, JJ brief Nd, editor. Trends in Long-acting Reversible Contraception Use Among US Women Aged 15–44. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gomez AM, Fuentes L, Allina A. Women or LARC First? Reproductive Autonomy And the Promotion of Long-Acting Reversible Contraceptive Methods. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2014;46:171–5. doi: 10.1363/46e1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wyatt KD, Anderson RT, Creedon D, et al. Women’s values in contraceptive choice: a systematic review of relevant attributes included in decision aids. BMC Women’s Health. 2014;14:28. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-14-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Potter J, Rubin SE, Sherman P. Fear of intrauterine contraception among adolescents in New York City. Contraception. 2014;89:446–50. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gomez AM, Clark JB. The Relationship Between Contraceptive Features Preferred by Young Women and Interest in IUDs: An Exploratory Analysis. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2014;46:157–63. doi: 10.1363/46e2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spies EL, Askelson NM, Gelman E, Losch M. Young women’s knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors related to long-acting reversible contraceptives. Womens Health Issues. 2010;20:394–9. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fleming KL, Sokoloff A, Raine TR. Attitudes and beliefs about the intrauterine device among teenagers and young women. Contraception. 2010;82:178–82. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2010.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmidt EO, James A, Curran KM, Peipert JF, Madden T. Adolescent Experiences With Intrauterine Devices: A Qualitative Study. Journal of Adolescent Health. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.05.001. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown MK, Auerswald C, Eyre SL, Deardorff J, Dehlendorf C. Identifying Counseling Needs of Nulliparous Adolescent Intrauterine Contraceptive Users: A Qualitative Approach. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2013;52:293–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weston MRS, Martins SL, Neustadt AB, Gilliam ML. Factors influencing uptake of intrauterine devices among postpartum adolescents: a qualitative study. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2012;206:40e1–e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.06.094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crabtree BF, Miller WL, editors. Doing Qualitative Research. 2. Sage Publications, Inc; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 22.DiCicco-Bloom B, Crabtree BF. The qualitative research interview. Medical Education. 2006;40:314–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Melo J, Peters M, Teal S, Guiahi M. Adolescent and Young Women’s Contraceptive Decision-Making Processes: Choosing “The Best Method for Her”. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2014.08.001. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yee L, Simon M. The Role of the Social Network in Contraceptive Decision-making Among Young, African American and Latina Women. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;47:374–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anderson N, Steinauer J, Valente T, Koblentz J, Dehlendorf C. Women’s Social Communication About IUDs: A Qualitative Analysis. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2014;46:141–8. doi: 10.1363/46e1814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuiper H, Miller S, Martinez E, Loeb L, Darney P. Urban adolescent females’ views on the implant and contraceptive decision-making: a double paradox. Family planning perspectives. 1997;29:167–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]