Abstract

Using measured free fraction and 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) values for the human immunodeficiency virus protease inhibitors lopinavir (LPV) and ritonavir (RTV) in tissue culture media with various protein concentrations ranging from 5 to 50%, we estimated serum-free IC50 values for each drug. The range of serum-free IC50 values (0.64 to 0.77 ng/ml for LPV and 3.0 to 5.0 ng/ml for RTV) did not exhibit a trend with increasing protein concentrations, despite a 10-fold difference in the free fraction value (0.006 to 0.063) for LPV and a 5-fold difference in the free fraction value (0.013 to 0.057) for RTV. The mean serum-free IC50 by the MTT-MT4 assay (0.69 ng/ml for LPV and 4.0 ng/ml for RTV) may be the most accurate parameter for the estimation of the inhibitory quotient (IQ), a relative measure of in vivo potency defined as the ratio of the minimal free drug concentration in plasma (Ctrough,free) for a specific patient population and the serum-free IC50. Using this approach, we calculated the average IQs for protease inhibitor-naïve patients for LPV and RTV to be 67 and 5.6, respectively.

Regardless of the therapeutic category, drugs exist in plasma in a dynamic equilibrium between drug bound to plasma proteins and unbound or free drug. The two major binding proteins are serum albumin and alpha-1 acid glycoprotein (AGP), though emerging evidence suggests that drug binding to lipoproteins, immunoglobulins, complement, and other plasma proteins may also be important. In humans, serum albumin (66 kDa) is present at approximately 40 mg/ml (600 μM) and AGP (40 kDa) is present at approximately 0.8 mg/ml (20 μM). In general, albumin binds acidic drugs with a high capacity, whereas basic drugs are often selectively bound to AGP with a high affinity. Due to the higher relative abundance of albumin, binding to albumin is less easily saturable than AGP binding. Since a protein-bound drug is generally considered to be too large to pass through most cell membranes to exert pharmacological actions, protein binding can affect the potency of drugs that exert pharmacological actions intracellularly. The magnitude of this effect can be estimated by the reduction of in vitro potency of a compound in the presence or absence of exogenously added serum (19).

Lopinavir (LPV) is a potent human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) protease inhibitor (PI) that is widely used for the therapeutic treatment of HIV infection as a coformulated combination with ritonavir (RTV), another PI that also enhances LPV levels in plasma by virtue of its inhibition of cytochrome P450-mediated metabolism (15, 28). Previous studies have shown that LPV and RTV are extensively bound to both albumin and AGP (19; A. Hsu, R. Bertz, D. Hickman, M. Emery, G. Kumar, J. Denissen, S. Vasavanonda, A. Molla, D. Kempf, G. R. Granneman, and E. Sun, 8th Conf. Retrovir. Opportunist. Infect., abstr. 753, 2001). Thus, the free fractions of LPV and RTV in HIV-infected patient plasma, determined by ultrafiltration, are 1.12 ± 0.21% and 1.99 ± 0.20%, respectively (Hsu et al., 8th Conf. Retrovir. Opportunist. Infect.). For an estimation of the effect of serum binding on the in vivo antiviral activity of LPV and RTV, the in vitro potency of each drug in a medium consisting of 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) and 50% heat-treated human serum (HS) in RPMI 1640 medium has been determined (19). Upon the addition of 50% HS, the mean 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) of LPV increased from 17 to 93 nM and that of RTV increased from 68 to 1,340 nM (19). However, the relatively modest attenuation of the activity of LPV (ca. six- to sevenfold) was lower than was anticipated based on the free fraction in human plasma, calling into question the relevance of in vitro assays that utilize 50% HS.

More generally, all currently available PIs except indinavir (IDV) are bound extensively to albumin and/or AGP, and the addition of HS or purified albumin or AGP attenuates the in vitro antiviral activity of these PIs to various degrees (3, 4, 17, 19). Clinical data also support the attenuation of potency by protein binding in vivo (5, 10). Assessing the effect of serum binding on the activity of PIs is essential for accurate estimations of the inhibitory quotient (IQ). Originally envisioned as a pharmacodynamic model for the in vivo activity of antibacterial agents (8), the IQ has been adapted for PIs as the minimal total drug concentration in plasma (Ctrough)/IC50 ratio. The IQ has been shown to be predictive of the virologic response to PI-based antiretroviral therapy (13, 29); however, there is wide disagreement on the optimal method for estimating the IQ based on in vitro assays (2, 20, 26). In vitro tissue culture assays maximally tolerate ca. 50% HS and may thus underestimate the effect of serum binding. In addition, the degree of attenuation of activity following the exogenous addition of purified serum proteins at physiological concentrations sometimes differs from that observed with HS. Furthermore, the effect of binding to the 10% FCS present in the culture medium has generally been ignored, even though the free fraction of different drugs may vary widely. Finally, disease, age, and other altered physiological states can often result in altered plasma compositions, the effect of which is difficult to assess in vitro. Consequently, there is a need for a standardized method for accurately assessing the relationship of in vitro activity and the IQ by quantitatively accounting for serum binding.

Theoretically, the determination of in vitro antiviral activity in a serum-free environment (IC50,free) coupled with the direct measurement of the free fraction in individual patient plasma samples should improve estimates of individual IQs, provided that only free drug is active. However, the in vitro IC50,free of PIs cannot be determined directly because FCS is required in the tissue culture medium to promote cell growth. Therefore, we have investigated a novel approach for quantitatively estimating the IC50,free of LPV and RTV that can be applied to other PIs and to many other classes of pharmaceutical compounds. This approach imputes IC50,free based on experimentally observed IC50 values (IC50,total) and free fractions for an appropriate concentration range.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

RPMI 1640 medium and 100× penicillin-streptomycin solution (PS) were obtained from Gibco BRL. FCS was obtained from JRH Bioscience. [14C]LPV (83.0 μCi/mg; labeled at the carbonyl carbon beta to the 2,6-dimethylphenoxy group and stored in ethanol) and [14C]RTV (35.56 μCi/mg; uniformly labeled in the valine group and stored in ethanol) were synthesized by John Uchic and Bruce Surber and purified (>99%) by Jia Du of the Drug Metabolism Department, Abbott Laboratories. Three stock solutions, with final concentrations of 0.02, 0.2, and 2.0 mg of labeled drug/ml, were prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide by dilution with appropriate amounts of cold drug in dimethyl sulfoxide. The radiochemical purity of the stock solutions was determined to be >98% by high-performance liquid chromatography with radioactivity flow detection. The stability of both drugs after incubation in the medium for the duration of the experiment was confirmed (≥98%) by the same method. All other materials were obtained commercially.

Protein binding.

FCS was combined with RPMI 1640-PS solution to prepare test media with 5, 10, 20, and 50% FCS, exactly analogous to the antiviral assay. Appropriate aliquots of the stock solutions were added to the FCS-medium aliquots to give initial [14C]LPV and [14C]RTV concentrations of approximately 0.1, 1.0, and 10.0 μg/ml. The spiked FCS aliquots were equilibrated for 15 min at 37°C before being loaded into dialysis cells. At least 2 ml of each spiked medium was incubated at 37°C for 3 h during the course of equilibrium dialysis. One milliliter was extracted and characterized by high-performance liquid chromatography to determine the drug stability in the test medium.

The binding affinities of [14C]LPV and [14C]RTV were determined with an equilibrium dialysis system (Spectrum Medical Industries, Los Angeles, Calif.) using 1-ml cells and a Spectra/Por 2 membrane with a molecular mass cutoff of 12,000 to 14,000 Da. Before being used, the membranes were soaked in distilled water for at least 15 min and then in 30% aqueous ethanol for 20 min. After being rinsed to remove the residual ethanol, the membranes were placed in the dialyzing medium (5, 10, 20, or 50% 0.02 M phosphate buffer [pH 7.4], containing 0.6% NaCl, in RPMI 1640-PS medium) for at least 15 min. The membranes were then placed between the two cell halves, and the cells were placed into the carrier. Triplicate cells were filled with dialyzing medium on the right side and with 5, 10, 20, or 50% FCS (about 1 ml)-containing [14C]LPV or [14C]RTV on the left side. The cell carrier was rotated at about 20 rpm for 3 h in a water bath maintained at approximately 37°C. Preliminary experiments established that equilibrium was attained in human plasma by 3 h (data not shown). At the end of the designated time interval, samples were removed from each side of the cells and saved for radioassays. The solutions were added to and removed from the cells via PE10 tubing attached to a 30-gauge needle and a 1-ml syringe.

Duplicate aliquots of all FCS and dialyzing medium samples were assayed directly in Insta-Gel (Packard) scintillation cocktail and counted in a Tri-Carb (Packard) model 2500TR liquid scintillation analyzer. Correction for quenching was done by automatic external standardization. The protein binding was calculated according to the following formula:

|

|

|

Determination of IC50 of LPV and RTV against wild-type HIV-1 (MTT-MT4 tissue culture system). Anti-HIV activity was assessed with the IIIB strain of wild-type HIV type 1 (HIV-1) in MT4 cells in media containing 5, 10, 20, and 50% FCS (identical to the media described above). The inhibition of HIV-1IIIB was measured in MT4 cells with a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.003, using 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) uptake as a measure of the HIV-induced cytopathic effect (19, 24). IC50 values for each of the four FCS concentrations were determined in two sets of six-replicate measurements.

Determination of Ki of LPV and RTV for wild-type HIV-1 protease.

Various concentrations of PIs were preincubated at room temperature with 5 nM recombinant HIV-1 protease for 10 min in a buffer consisting of 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.0), 125 mM potassium acetate, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM EDTA, 0.25 mg of bovine serum albumin/ml, and 5% dimethyl sulfoxide in a white 96-well plate. Reactions were initiated by the addition of the fluorogenic substrate (3.5 μM final concentration) DABCYL-GABA-Ser-Gln-Asn-Tyr-Pro-Ile-Val-Gln-EDANS (18). The fluorescence changes were monitored for 30 min at room temperature by use of a Fluoroskan II plate reader equipped with a 355 nm-485 nm filter pair. Initial velocities were plotted against inhibitor concentrations and fit to the following equation (22) by nonlinear regression to establish the Ki values:

|

where A = αVmax[S]/2(Km + [S]) (α is a factor to convert fluorescence units to a molar concentration); Ki′ = Ki(1 + [S]/Km); and It and Et represent the total inhibitor and active enzyme concentrations, respectively.

RESULTS

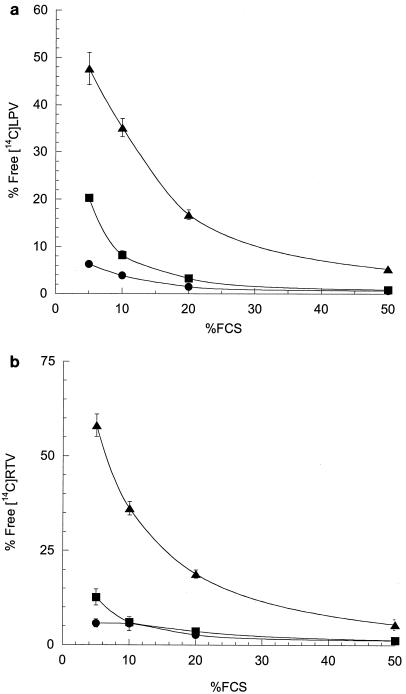

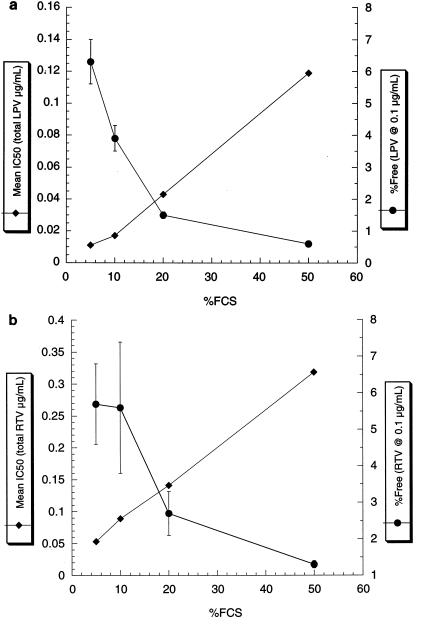

In order to determine the IC50,free of LPV and RTV, we first measured the free fraction of each drug in media containing different amounts of FCS. The protein binding of both LPV and RTV to FCS was saturable, with the free fraction of LPV ranging from 0.6% at 0.1 μg of drug/ml with 50% FCS to 47.7% at 10 μg of drug/ml with 5% FCS (Fig. 1). Notably, under conditions that are normally used for antiviral determinations (10% FCS), LPV (from 0.1 to 10 μg/ml) was 65 to >95% bound, indicating that even in the absence of HS, in vitro IC50 values underestimate the innate (serum-free) potency of this compound. Similarly, the free fraction of RTV ranged from 1.3 to 58.1%, indicating that both drugs are substantially bound by 5 to 50% FCS. The IC50 values for both LPV and RTV based on the total drug concentration (IC50,total) increased incrementally as the % FCS in the medium increased. The general inverse relationship between the free fraction at 0.1 μg of drug/ml and the IC50 over a range of 5 to 50% FCS is shown in Fig. 2. The mean IC50,total of LPV ranged from 0.011 to 0.119 μg/ml (Table 1), and the mean IC50,total of RTV ranged from 0.053 to 0.318 μg/ml (Table 2). Since the IC50,total values for both drugs at the highest levels of serum only marginally exceeded 0.1 μg/ml (the lowest concentration at which the free fraction could be accurately determined), the free fractions determined at that drug concentration (0.1 μg/ml) were used to calculate the IC50,free values. Extrapolation and interpolation of the free fraction of each drug to the concentration representing the IC50,total provided similar results, indicating that the free fractions of both drugs (over the range of IC50,total values) did not deviate significantly from those determined at 0.1 μg/ml (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Effect of FCS on free fractions of [14C]LPV and [14C]RTV in RPMI 1640-PS. Binding was determined at 0.1 (•)-, 1 (▪)-, and 10 (▴)-μg/ml drug concentrations. The means of triplicate experiments are shown with error bars indicating the standard deviations. When no error bars are apparent, the errors fall within the area of the symbol. Percent free is the free fraction × 100. (a) LPV; (b) RTV.

FIG. 2.

Effect of FCS on drug IC50 (♦) and mean % free drug (at 0.1 μg/ml; •) in RPMI 1640-PS. For IC50 values, the symbols represent the means of duplicate determinations. For protein binding, the means of triplicate experiments are shown with error bars indicating the standard deviations. When no error bars are apparent for protein binding, the errors fall within the area of the symbol. (a) LPV; (b) RTV.

TABLE 1.

Mean LPV IC50,total, % free LPV, and derived LPV IC50,free in medium containing 5 to 50% FCS

| % FCS in culture medium | LPV IC50,total (ng/ml) | LPV free fraction (%)a | LPV IC50,free (ng/ml)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 11 ± 7 | 6.3 ± 0.7 | 0.69 ± 0.44 |

| 10 | 17 ± 4 | 3.9 ± 0.4 | 0.68 ± 0.14 |

| 20 | 43 ± 15 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 0.64 ± 0.23 |

| 50 | 119 ± 21 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.77 ± 0.14 |

Free fraction of 0.1-μg/ml LPV for each FCS concentration (mean ± SD; n = 3).

Calculated as the product of the mean LPV free fraction and the individual LPV IC50,total (mean ± SD; n = 2). The mean LPV IC50,free for all FCS concentrations was 0.69 ± 0.06 ng/ml.

TABLE 2.

Mean RTV IC50,total, % free RTV, and derived RTV IC50,free in medium containing 5 to 50% FCS

| % FCS in culture medium | RTV IC50,total (ng/ml) | RTV free fraction (%)a | RTV IC50,free (ng/ml)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 53 ± 26 | 5.7 ± 1.1 | 3.0 ± 1.5 |

| 10 | 89 ± 14 | 5.6 ± 1.8 | 5.0 ± 0.8 |

| 20 | 141 ± 40 | 2.7 ± 0.6 | 3.8 ± 1.1 |

| 50 | 318 ± 66 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 4.0 ± 0.8 |

Free fraction of 0.1-μg/ml RTV for each FCS concentration (mean ± SD; n = 3).

Calculated as the product of the mean RTV free fraction and the individual RTV IC50,total (mean ± SD; n = 3). The mean RTV IC50,free for all FCS concentrations was 4.4 ± 0.8 ng/ml.

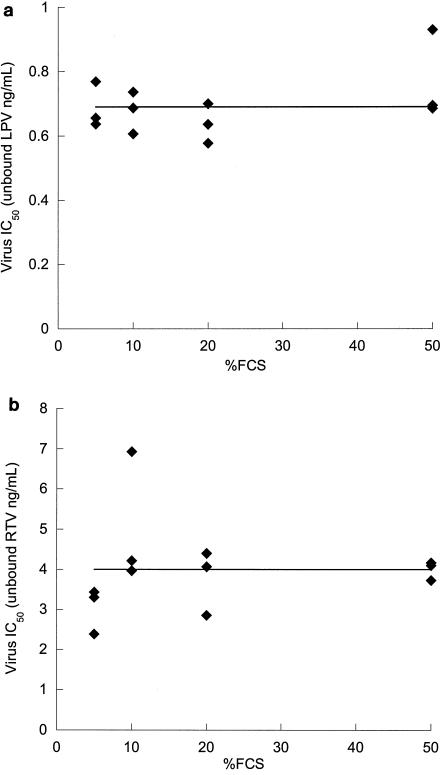

The IC50,free for each set of in vitro conditions was calculated as the product of the IC50,total and the free fraction. These data are summarized in Tables 1 and 2 for LPV and RTV, respectively. Importantly, the serum-free IC50 values for both drugs remained constant over a wide range (from 5 to 50%) of FCS concentrations (Fig. 3), representing a 10-fold range in free fractions for LPV and a 5-fold range in free fractions for RTV (P = 0.24 and 0.92 for linear regression lines based on the null hypothesis that the slope = 0 for LPV and RTV, respectively). The average IC50,free values for LPV and RTV against the wild-type virus across the range of 5 to 50% FCS were 0.00069 μg/ml (0.69 ng/ml) and 0.0040 μg/ml (4.0 ng/ml), respectively.

FIG. 3.

Estimation of serum-free IC50 of LPV and RTV. Each symbol represents the product of the mean IC50,total for virus inhibition (n = 2) and the fraction of unbound drug in the medium determined in triplicate at 0.1 μg/ml by equilibrium dialysis. The horizontal lines represent the mean IC50,free values. (a) LPV; (b) RTV.

The IC50,free values determined in the present study were used to calculate the mean IQs for LPV and RTV by using the following equation: IQ = Ctrough × free fraction100% human plasma/IC50,free. For LPV, the free fraction determined by equilibrium dialysis was 0.0066 and the Ctrough after a combined 400- and 100-mg (LPV and RTV, respectively) dose given twice a day (BID) was 7.7 and 5.5 μg/ml, with and without regard to food, respectively (R. Bertz, C. Renz, C. Foit, J. Swerdlow, X. Ye, O. Jasinsky, A. Hsu, G. R. Granneman, and E. Sun, 2nd Int. Workshop Clin. Pharmacol. HIV Ther., abstr. 3.10, 2001; Hsu et al., 8th Conf. Retrovir. Opportunist. Infect.). For RTV, the free fraction was 0.006 and the Ctrough after a 600-mg dose given BID was 3.9 μg/ml, with no demonstrable effect of food (Bertz et al., 2nd Int. Workshop Clin. Pharmacol. HIV Ther.; Hsu et al., 8th Conf. Retrovir. Opportunist. Infect.). Therefore, the mean IQs for LPV in patients with wild-type HIV calculated by the IC50,free method were 67 and 52, with and without regard to food, respectively, and the mean IQ for RTV (600 mg BID) in patients was 5.6, with or without food. These values were comparable to the IQs that were previously estimated by using IC50 values determined in the presence of 50% HS and 10% FCS (78 for LPV and 3.9 for RTV) (23; Bertz et al., 2nd Int. Workshop Clin. Pharmacol. HIV Ther.), suggesting that IC50 values determined with 50% HS provide a reasonable approximation of the activities of these PIs in vivo.

We also investigated whether the IC50,free provides a more accurate assessment of the inherent potency of PIs than the IC50,total. To this end, we determined the Kis of LPV and RTV for purified HIV protease at pH 7.0 by using a fluorogenic assay. For comparison, we measured the Ki of IDV, a PI that is only ca. 60% bound in human plasma (1) and is likely to be largely unbound in culture medium containing only 10% FCS (hence, we assume that the IC50,total reasonably approximates the IC50,free). The ratio of IC50,total (measured with 10% FCS) to Ki varied widely among the three PIs (range, 68 for IDV to 2,070 for LPV) (Table 3), suggesting that there is no strong correlation between the inherent enzymatic inhibitory potency and the IC50,total. In contrast, the IC50,free/Ki ratios for LPV and RTV were remarkably similar (84 and 28, respectively) to the IC50,total/Ki ratio of IDV (68) (Table 3). These results provide additional evidence that only the free concentration of PIs contributes to their antiviral activity.

TABLE 3.

IC50/Ki ratios for PIs

| Drug | Ki (pg/ml)a | IC50,total (ng/ml) | IC50,free (ng/ml) | IC50,total/Ki ratio | IC50,free/Ki ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LPV | 8.2 ± 3.9 | 17 ± 4b | 0.69 ± 0.06c | 2,070 | 84 |

| RTV | 154 ± 22 | 89 ± 14d | 4.4 ± 0.8c | 578 | 28 |

| IDV | 337 ± 69 | 23 ± 5e | NDf | 68 | NDf |

Ki values were determined from a 13-point dose-response curve (see Materials and Methods). The numbers reported are means ± standard errors.

Mean ± SD (n = 2).

Mean ± SD (n = 4).

Mean ± SD (n = 3).

Previously determined IC50 for wild-type HIVIIIB in 10% FCS-containing culture medium (13).

ND, not done.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we determined the serum-free IC50 of LPV and RTV, two HIV PIs that are commonly used for the treatment of HIV infection. As the free fractions of the two drugs declined upon an incremental increase in FCS in the medium, the observed IC50,total values increased accordingly. Notably, these results confirm the findings of others by different methods that the pharmacological activity of PIs (and likely that of drugs of many other classes) is exclusively a function of the free (unbound) concentration, since the product of the IC50, total and the free fraction was a constant value over a wide range of free fractions. Consequently, a single IC50 value combined with a single free fraction determination using that tissue culture medium (e.g., 10% FCS) should be sufficient for a relatively rapid estimation of the IC50,free. The serum-free IC50 values for LPV and RTV determined by this method with the MT4-MTT tissue culture system (0.69 and 4.0 ng/ml, respectively) provide a new estimate of in vitro activity that is independent of protein binding. As such, these values are useful for assessing LPV and RTV in vivo activity when binding to patient plasma is taken into account.

The results presented here resolve the apparent inconsistency between measurements of the free fractions of PIs in human plasma and the observed attenuation of in vitro activity upon the addition of HS to the tissue culture medium. For example, LPV is >98% bound in human plasma, but its potency is only affected ca. sevenfold in the presence of 50% HS (18). However, the inconsistency in these findings is based on the assumption that binding by the 10% FCS present in the assay medium that does not contain HS is insignificant. The present study demonstrates that PIs can be substantially bound by relatively small amounts of FCS (0.1 μg of LPV or RTV/ml is ca. 96 and 94% bound, respectively, in 10% FCS). Consequently, the observed shift in IC50 between “low serum” (i.e., 10% FCS) and “high serum” (10% FCS plus 50% HS) conditions reflects the incremental change in free fractions between the two experimental conditions. The free fraction of LPV in 10% FCS measured in this study (3.9%) is approximately sixfold higher than that observed in medium containing 10% FCS plus 50% HS (0.65%) (Hsu et al., 8th Conf. Retrovir. Opportunist. Infect.), which is entirely consistent with the observed change in IC50. These results also indicate that IC50 values determined in 50% HS plus 10% FCS are a relatively reliable approximation of the serum-adjusted activity of these PIs, since the free fractions in the above medium are not expected to differ greatly from the free fractions in 100% human plasma.

In contrast, IC50 values determined without HS (but by necessity in the presence of FCS) may vary widely for inhibitors of similar biochemical potencies (e.g., for PIs, the inhibition of HIV protease activity) partly because of large differences in free fractions in the presence of FCS. These IC50 values are therefore of limited utility in assessing in vivo potency unless the free fraction under the conditions of the assay is measured and taken into account. Likewise, the addition of purified HS proteins, e.g., AGP and albumin, provide information on the relative impact of these proteins on the in vitro IC50. However, without a measure of the free fraction, the extrapolation of in vitro activity to the estimation of in vivo potency may not be quantitative. Our results suggest that for a particular in vitro assay system, the product of the measured IC50 and the free fraction under any set of conditions (using either HS, FCS, or purified serum proteins) will give approximately the same estimated serum-free IC50.

The substantial binding of PIs to FCS also partially accounts for the discrepancy observed between the biochemical potency (Ki for HIV protease inhibition) and virological activity (IC50 in vitro). The often large difference between these values, which are based on the IC50,total, can vary substantially among different PIs (Table 3) and has generally been ascribed to limited cellular penetration. However, the IC50,free/Ki ratios for LPV and RTV (Table 3) are essentially equivalent to the IC50,total/Ki ratio for IDV, a largely unbound drug, indicating that a substantial portion of the potency gap between the biochemical and virological assays is due to binding by FCS. Thus, determination of the serum-free IC50 values provides insight into the mechanism of the antiviral activity of PIs. The remainder of the difference between Ki and IC50,free values was relatively similar for the three PIs examined (28- to 84-fold) and is presumably a combination of cellular penetration, differences in substrate and assay conditions, and the fact that more or less than 50% inhibition of HIV protease activity may be necessary for a 50% inhibition of viral replication. The consistency of IC50,free/Ki ratios across multiple PIs additionally suggests that the free concentration is wholly responsible for the PI antiviral activity.

The present results provide a pharmacologically relevant method for estimating the IQs of PIs. Previously, we demonstrated that the average IQ, as estimated by the ratio of Ctrough to IC50 (determined in 10% FCS plus 50% HS), is associated with the virologic efficacy of PIs (13, 29). The present method can account for intersubject variability in the free fraction, particularly in special populations with altered serum compositions (14, 21, 25), and allows for the estimation of individual patient IQs, if desired. The mean IQ values for LPV in patients with wild-type HIV calculated by this method are 67 and 52, with and without regard to food, respectively, and the mean IQ for RTV (600 mg BID) in patients is 5.6, with or without food. These values are similar to those that were previously calculated based on the IC50 determined in 10% FCS plus 50% HS (78 and 3.9, respectively). Thus, mean IQ values based on IC50 values determined with 50% HS have been providing a relatively realistic estimation of in vivo efficacy.

The pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic approach provided by the IQ model presented here, using the determination of the serum-free IC50, is complementary to Emax models that have been applied to the exposure-response relationships of many drugs, including HIV PIs (11, 12, 27, 30). Emax approaches for antiretroviral therapy suffer from certain limitations, however. If bioavailability is limited, the maximal effect of the dose-response curve may not be achieved (30). With potent drugs that produce large decreases in the viral load (i.e., high Emax), the maximal effects may be underestimated by the sensitivity of the viral load assay or by the limited decay rate of plasma HIV RNA during initial therapy. Moreover, an accurate determination of the in vivo 50% effective concentration requires treatment with monotherapy, at least over the short-term, which may not be practical for compounds with low genetic barriers to resistance. The IQ model potentially provides a complementary approach to characterizing pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic relationships, particularly for drugs with average levels in plasma that produce a maximal effect (e.g., boosted PIs), when estimation of the 50% effective concentration is not possible. Given our inability to cure HIV infections because integrated proviral DNA is capable of producing infectious RNA (9), a more complete suppression resulting from high therapeutic concentrations, although not easily measured in short-term studies, could significantly impact the durability of the response (7, 16). Finally, since it is based on in vitro and pharmacokinetic data (the latter of which may be estimated by using preclinical data), the IQ model may be useful for the evaluation of potential candidate compounds prior to clinical development.

The calculation of IQ by using the serum-free IC50 suffers from several limitations as well. In this study, we have used equilibrium dialysis, which gives a 1.7-fold lower free fraction than ultrafiltration (data not shown), illustrating the challenge in accurately determining the free fraction of highly bound drugs and the importance of consistency in the method employed. In addition, the IC50,free was determined by using a particular tissue culture assay. At constant serum levels (e.g., 10% FCS), in vitro assays that use different cell lines, different wild-type variants of HIV, different detection methods, and different replication systems (e.g., single versus multiple replication cycle) can produce substantially different IC50 values for a given inhibitor. In the model presented here, we have used the MT4-MTT assay (24), which uses a relatively high MOI. As such, this assay might provide a more realistic assessment of in vivo potency, as the MOI values may be large in vivo. Because of the high MOI, this assay generally produces observed IC50 values that are higher than those from some other assays, for example, single-cycle assays that are routinely used for HIV resistance testing (6). Thus, the IQ model based on this assay is conservative in that it provides a lower estimate of drug potency than many other models. Regardless of the in vitro assay employed for the calculation of the IQ, it is of utmost importance that the method be standardized to allow for comparisons of different agents and subsequently validated with clinical data. The correlation of the clinical response to LPV-RTV and IDV-RTV combinations in PI-experienced patients with the IQ of the PI suggests that this conservative model is useful for understanding PI pharmacodynamics (13, 29). However, this method may be less applicable to drugs that undergo intracellular metabolism to active forms (such as nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors). For such drugs, differences in the intracellular half-life can impact the in vivo potency in ways that may not be reflected in vitro.

In summary, we have described a general method for quantitatively assessing the effect of serum binding on the activity of HIV protease inhibitors. Binding to serum proteins has previously been shown to be clinically relevant for this class of compounds (3, 4, 5, 10, 17). The present results confirm that it is only the free fraction of these agents that is active. This method also provides a quantitative approach for the comparison of IQ values for different PIs and allows for the assessment of in vivo potency within individual patients. Finally, this method provides a framework for the evaluation of other classes of drugs that are bound by serum proteins but require the presence of serum for in vitro evaluation.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge A. Molla and H. Mo, in whose laboratories the antiviral activities were determined by S. Vasavanonda. We also gratefully acknowledge Bruce Surber and John Uchic for the synthesis of radiolabeled ritonavir and lopinavir.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson, P. L., R. C. Brundage, L. Bushman, T. N. Kakuda, R. P. Remmel, and C. V. Fletcher. 2000. Indinavir plasma protein binding in HIV-1-infected adults. AIDS 14:2293-2297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Becker, S., A. Fisher, C. Flexner, J. G. Gerber, R. Haubrich, A. D. M. Kashuba, A. D. Luber, and S. C. Piscitelli. 2001. Pharmacokinetic parameters of protease inhibitors and the Cmin/IC50 ratio: call for consensus. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 27:210-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bilello, J. A., P. A. Bilello, M. Prichard, T. Robins, and G. L. Drusano. 1995. Reduction of the in vitro activity of A77003, an inhibitor of human immunodeficiency virus protease by human serum α1 acid glycoprotein. J. Infect. Dis. 171:546-551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bilello, J. A., P. A. Bilello, K. Stellrecht, J. Leonard, D. W. Norbeck, D. J. Kempf, T. Robins, and G. L. Drusano. 1996. Human serum α1 acid glycoprotein reduces uptake, intracellular concentration, and antiviral activity of A-80987, an inhibitor of the human immunodeficiency virus type-1 protease. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:1491-1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bilello, J. A., and G. L. Drusano. 1996. Relevance of plasma protein binding to antiviral activity and clinical efficacy of inhibitors of human immunodeficiency virus protease. J. Infect. Dis. 173:1524-1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Condra, J. H., C. J. Petropoulos, R. Ziermann, W. A. Schleif, M. Shivaprakash, and E. A. Emini. 2000. Drug resistance and predicted virologic responses to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease inhibitor therapy. J. Infect. Dis. 182:758-765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drusano, G. L., J. A. Bilello, D. S. Stein, M. Nessly, A. Meibohm, E. A. Emini, P. Deutsch, J. Condra, J. Chodakewitz, and D. J. Holder. 1998. Factors influencing the emergence of resistance to indinavir: role of virologic, immunologic and pharmacologic variables. J. Infect. Dis. 178:360-367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ellner, P. D., and H. C. Neu. 1981. The inhibitory quotient. A method for interpreting minimum inhibitory concentration data. JAMA 246:1575-1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Finzi, D., M. Hermankova, T. Pierson, L. M. Carruth, C. Buck, R. E. Chaisson, T. C. Quinn, K. Chadwick, J. Margolick, R. Brookmeyer, J. Gallant, M. Markowitz, D. D. Ho, D. D. Richman, and R. F. Siliciano. 1997. Identification of a reservoir for HIV-1 in patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy. Science 278:1295-1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fischl, M. A., D. D. Richman, C. Flexner, M. F. Para, R. Haubrich, A. Karim, P. Yeramian, J. Holdenwiltse, and P. M. Meehan. 1997. Phase I/II study of the toxicity, pharmacokinetics, and activity of the HIV protease inhibitor SC-52151. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. Hum. Retrovirol. 15:28-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gatti, G., E. Pontali, S. Boni, C. R. De Pascalis, M. Bassetti, and D. Bassetti. 2002. The relationship between ritonavir plasma trough concentration and virological and immunological response in HIV-infected children. HIV Med. 3:125-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gatti, G., A. Vigano, N. Sala, S. Vella, M. Bassetti, D. Bassetti, and N. Principi. 2000. Indinavir pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in children with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:752-755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsu, A., J. Isaacson, S. Brun, B. Bernstein, W. Lam, R. Bertz, C. Foit, K. Rynkiewicz, B. Richards, M. King, R. Rode, D. J. Kempf, G. R. Granneman, and E. Sun. 2003. Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic analysis of lopinavir-ritonavir in combination with efavirenz and two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors in extensively pretreated human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:350-359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kays, M. B., R. L. White, G. Gatti, and J. G. Gambertoglio. 1992. Ex vivo protein binding of clindamycin in sera with normal and elevated alpha 1-acid glycoprotein concentrations. Pharmacotherapy 12:50-55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kempf, D. J., K. C. Marsh, G. Kumar, A. D. Rodrigues, J. F. Denissen, E. McDonald, M. J. Kukulka, A. Hsu, G. R. Granneman, P. A. Baroldi, E. Sun, D. Pizzuti, J. J. Plattner, D. W. Norbeck, and J. M. Leonard. 1997. Pharmacokinetic enhancement of inhibitors of the human immunodeficiency virus protease by coadministration with ritonavir. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:654-660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kempf, D. J., R. A. Rode, Y. Xu, E. Sun, M. E. Heath-Chiozzi, J. Valdes, A. J. Japour, S. Danner, C. Boucher, A. Molla, and J. M. Leonard. 1998. The duration of viral suppression during protease inhibitor therapy for HIV-1 infections is predicted by plasma HIV-1 RNA at the nadir. AIDS 12:F9-F14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lazdins, J. K., J. Mestan, G. Goutte, M. R. Walker, G. Bold, H. G. Capraro, and T. Klimkait. 1997. In vitro effect of α1-acid glycoprotein on the anti-human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) activity of the protease inhibitor CGP 61755: a comparative study with other relevant HIV protease inhibitors. J. Infect. Dis. 175:1063-1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matayoshi, E. D., G. T. Wang, G. A. Krafft, and J. Erickson. 1990. Novel fluorogenic substrates for assaying retroviral proteases by resonance energy transfer. Science 247:954-958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Molla, A., S. Vasavanonda, G. Kumar, H. L. Sham, M. Johnson, B. Grabowski, J. F. Denissen, W. Kohlbrenner, J. J. Plattner, J. M. Leonard, D. W. Norbeck, and D. J. Kempf. 1998. Human serum attenuates the activity of protease inhibitors toward wild-type and mutant human immunodeficiency virus. Virology 250:255-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Montaner, J., A. Hill, and E. Acosta. 2001. Practical implications for the interpretation of minimum plasma concentration/inhibitory concentration ratios. Lancet 357:1438-1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morita, K., and A. Yamaji. 1995. Changes in the serum protein binding of vancomycin in patients with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection: the role of serum alpha 1-acid glycoprotein levels. Ther. Drug Monit. 17:107-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morrison, J. F., and S. R. Stone. 1985. Approaches to the study and analysis of the inhibition of enzymes by slow- and tight-binding inhibitors. Mol. Cell. Biophys. 2:347-368. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murphy, R. L., S. Brun, C. Hicks, J. T. Eron, R. Gulick, M. King, A. C. White, C. Benson, M. Thompson, H. A. Kessler, S. Hammer, R. Bertz, A. Hsu, A. Japour, and E. Sun. 2001. ABT-378/ritonavir plus stavudine and lamivudine for the treatment of antiretroviral-naive adults with HIV-1 infection: 48-week results. AIDS 15:F1-F9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pauwels, R., J. Balzarini, M. Baba, R. Snoeck, D. Schols, P. Herdewijn, J. Desmyter, and E. De Clercq. 1988. Rapid and automated tetrazolium-based colorimetric assay for the detection of anti-HIV compounds. J. Virol. Methods 20:309-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paxton, J. W., and R. H. Briant. 1984. Alpha 1-acid glycoprotein concentrations and propranolol binding in elderly patients with acute illness. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 18:806-810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Piliero, P. J. 2002. The utility of inhibitory quotients in determining the relative potency of protease inhibitors. AIDS 16:799-800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sadler, B. M., C. Gillotin, Y. Lou, and D. S. Stein. 2001. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of the human immunodeficiency virus protease inhibitor amprenavir after multiple oral dosing. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:30-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sham, H. L., D. J. Kempf, A. Molla, K. C. Marsh, G. N. Kumar, C.-M. Chen, W. Kati, K. Stewart, R. Lal, A. Hsu, D. Betebenner, M. Korneyeva, S. Vasavanonda, E. McDonald, A. Saldivar, N. Wideburg, X. Chen, P. Niu, C. Park, V. Jayanti, B. Grabowski, G. R. Granneman, E. Sun, A. J. Japour, J. M. Leonard, J. J. Plattner, and D. W. Norbeck. 1998. ABT-378, a highly potent inhibitor of the human immunodeficiency virus protease. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:3218-3224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shulman, N., A. Zolopa, D. Havlir, A. Hsu, C. Renz, S. Boller, P. Jiang, R. Rode, J. Gallant, E. Race, D. J. Kempf, and E. Sun. 2002. Virtual inhibitory quotient predicts response to ritonavir boosting of indinavir-based therapy in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients with ongoing viremia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:3907-3916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vanhove, G. F., J. M. Gries, D. Verotta, L. B. Sheiner, R. Coombs, A. C. Collier, and T. F. Blaschke. 1997. Exposure-response relationships for saquinavir, zidovudine, and zalcitabine in combination therapy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:2433-2438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]