Abstract

Introduction

Knee osteoarthritis (OA) is one of the most common chronic diseases worldwide and is associated with significant pain and disability. Clinical practice guidelines consistently recommend weight management as a core aspect of care for overweight and obese patients with knee OA; however, provision of such care is suboptimal. Telephone-based interventions offer a novel approach to delivery of weight management care in these patients. The aim of the proposed study is to assess the effectiveness of referral to a telephone-based weight management and healthy lifestyle programme, previously shown to be effective in changing weight, in improving knee pain intensity in overweight or obese patients with knee OA, compared to usual care.

Methods and analysis

A parallel, randomised controlled trial will be undertaken. Patients with OA of the knee who are waiting for an outpatient orthopaedic consultation at a tertiary referral public hospital within New South Wales, Australia, will be allocated to either an intervention or a control group (1:1 ratio). After baseline data collection, patients in the intervention group will receive a 6-month telephone-based intervention, and patients in the control group will continue with usual care. Surveys will be conducted at baseline, 6 and 26 weeks post-randomisation. The study requires 60 participants per group to detect a two-point difference in pain intensity (primary outcome) 26 weeks after baseline.

Ethics and dissemination

The study is approved by the Hunter New England Health Human Research Ethics Committee (13/12/11/5.18) and the University of Newcastle Human Research Ethics Committee (H-2015-0043). The results will be disseminated in peer-reviewed journals and at scientific conferences.

Trial registration number

ACTRN12615000490572, Pre-results.

Keywords: PAIN MANAGEMENT

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The protocol describes the first randomised trial to assess the effectiveness of a telephone-based weight loss intervention for managing patients with knee osteoarthritis who are waiting for orthopaedic consultation.

The trial uses a robust pragmatic design replicating usual practice. The results will be highly informative for healthcare decision and generalisable to routine practice.

The telephone-based model may exclude some patients with severe disabling symptoms who do not have independent mobility.

Background

Osteoarthritis (OA) of the knee is the most common joint condition and causes significant amounts of disability worldwide.1 2 The aetiology of OA is multifactorial including mechanical, inflammatory, metabolic and social factors leading to chronic pain, stiffness and reduced joint function.3 According to the 2010 Global Burden of Disease Study, OA contributed to more than 17 million years lived with disability, 83% of which was attributed to OA of the knee.2 In 2013, there were over 240 million cases of OA reported worldwide.4 As a consequence, OA imposes a significant economic burden on individuals and society.5 6 The cost of OA has previously been recorded to account for between 1% and 2.5% of the gross national product in the UK, the USA, Canada, France and Australia.7 The knee is the most common and burdensome joint affected by OA, with a lifetime prevalence of knee OA of 40% in men and 47% in women.8

There are many risk factors for knee OA, including non-modifiable factors such as being female, or aged over 45 years, and advancing age, and modifiable behavioural factors such as excess weight, inactivity and joint injury.8 Being overweight or obese is the single most important modifiable behavioural risk factor for the onset and progression of knee OA.9–11 Increased mechanical load on joints, increased inflammatory mediators contributing to joint degradation and other systemic metabolic effects9 12 are suggested as underlying mechanisms for the relationship between excess weight and OA. Importantly, weight loss interventions reduce pain and disability in overweight or obese patients with knee OA.13 14 A systematic review and meta-analysis of four randomised controlled trials (RCT) reported that behavioural weight loss interventions lead to moderate improvements in pain and physical function (pooled effect sizes 0.2 and 0.23, respectively) for adults with knee OA who are overweight or obese.14 Further analysis showed that achieving at least 5% weight loss was a precursor to symptom improvement.14

Clinical practice guidelines consistently recommend several core treatments for patients with knee OA including routine provision of weight loss care; advice and education about the condition; and advice on general low-impact aerobic fitness and muscle strengthening exercises.15–19 Guidelines recommend that these treatments be provided to all patients with knee OA irrespective of age, comorbidity, stage or severity of the condition or the setting of care, and prior to surgical interventions.15–19 However, the provision of such care across all healthcare settings is suboptimal.20–23 Data from the Australian Bettering the Evaluation and Care of Health Study reveals, on average, that only 18 in 100 people with knee OA attending a general practitioner (GP) were provided with lifestyle management (including weight management), while 12 in 100 were referred for orthopaedic consultation.21 A recent Australian study of patients with hip or knee OA awaiting orthopaedic consultation found that only 20% felt they had received education about their condition, prognosis and treatment options.22 Although 89% of patients were overweight or obese, only 22% reported that they engaged in weight loss strategies, and <25% had been supported to undertake physical activity.22 These results indicate that the majority of patients are referred for orthopaedic consultation without having previously attempted any lifestyle modification, and in particular, weight loss interventions.22 24

Traditionally, behavioural interventions targeting weight and activity have been provided to patients in clinical face-to-face programmes.25 While such face-to-face interventions have achieved weight loss between 5% and 12% when targeting behaviour changes including diet and exercise in people with knee OA,14 26 these modes of delivery have limited accessibility and reach due to the lack of availability of clinicians to provide interventions, their high cost, and the time and travel requirements for patients.27 28 The development of more accessible modes of care could improve the delivery of care to support behaviour change, weight loss and increased physical activity for patients with knee OA. Encouragingly, behavioural interventions for physical activity, diet and weight loss delivered by telephone have been shown to be just as effective as face-to-face interventions in the general population,27 29 yet their reach is far greater. Systematic reviews have found strong evidence to support the efficacy of telephone-delivered interventions for improving the behavioural determinants of weight, diet and physical activity in both healthy participants and those with chronic disease.30 31 Four RCTs using telephone-based coaching interventions to reduce pain in adults with knee OA have been conducted.29 32–34 These multicomponent interventions targeted several patient behaviours such as mobility, medication compliance, stress control, weight management, improved sleep quality and increased communication with healthcare providers with the goal to improve overall self-management. These previous studies provide evidence to support telephone as an effective and acceptable modality for care delivery among this patient group.29 32–34 While weight loss is a core recommendation for patients with knee OA, and was included in one of the prior studies as a small subcomponent, none of these previous studies primarily focused on weight loss. We have chosen to test this in a pragmatic trial by referring patients to an existing telephone-based weight loss intervention.

The primary objective of this trial is to assess the effectiveness of referral to a telephone-based weight management and healthy lifestyle programme in reducing the intensity of knee pain in overweight or obese patients with knee OA who are referred for outpatient orthopaedic consultation, compared with usual care. Secondary objectives are to assess if the intervention improves disability and function, anthropometry (weight, body mass index (BMI) and waist circumference), quality of life, diet, physical activity and healthcare usage compared with usual care at 26 weeks.

Methods

Study design and setting

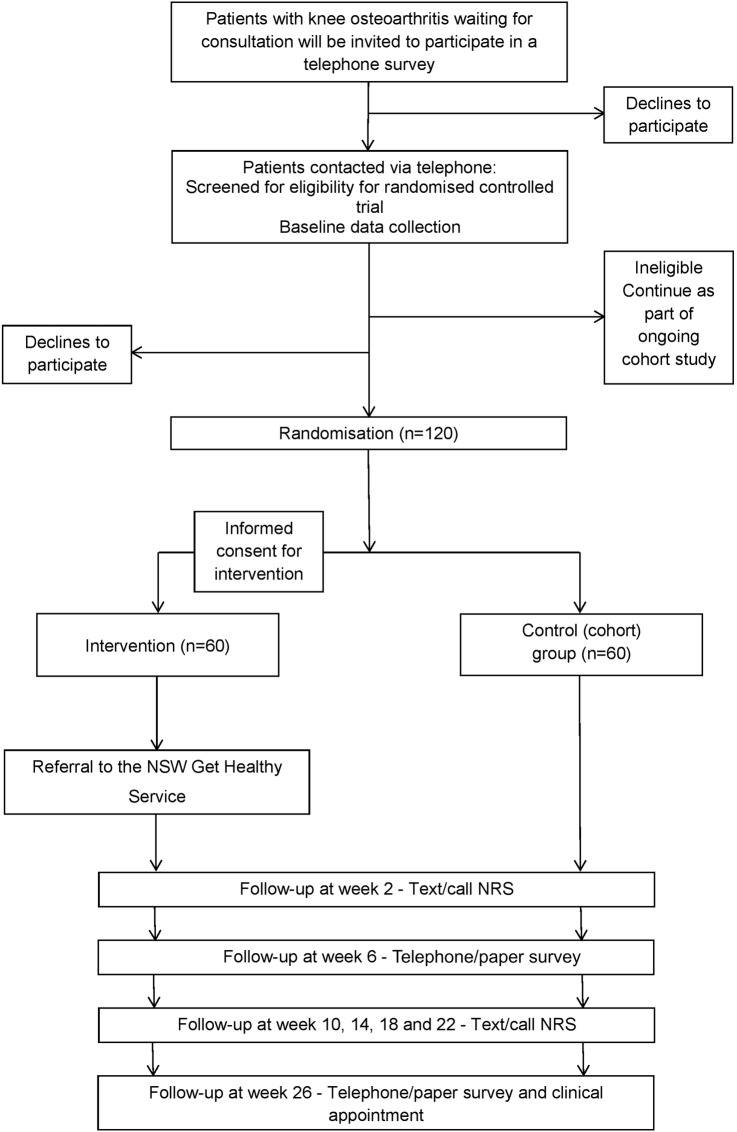

The study will employ a parallel group randomised controlled design (figure 1). The trial is part of a cohort multiple RCT,35 which has been embedded into routine service. This pragmatic design uses participants from our existing cohort of patients waiting for orthopaedic consultation; patients are randomised to be offered a new clinical intervention (intervention group), or to remain part of the cohort (control group). As the trial is presented as routine service, only the patients randomised to the intervention group are made aware of the intervention components. The control group is unaware of the intervention group and is asked to participate in routine follow-up for the cohort, and is informed that a clinical appointment will be available in the next 6 months. The design and conduct of this trial will adhere to the requirements of the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT).36

Figure 1.

Flow diagram describing progress of participants through the study.

Participants and recruitment

The trial will involve 120 patients with OA of the knee who are waiting for an outpatient orthopaedic consultation at a tertiary referral public hospital within New South Wales (NSW), Australia. In Australia, patients referred for orthopaedic consultation are categorised according to urgency of consultation: urgent—to be seen within 30 days; semi-urgent—to be seen within 90 days; and non-urgent—to be seen within 12 months.37

All patients over 18 years of age who are overweight or obese, waiting for an outpatient orthopaedic consultation for knee OA will be sent a letter inviting them to take part in a telephone survey as part of the ongoing cohort study. Patients will be provided a telephone number to contact if they do not wish to take part in the survey, or can refuse on receipt of the telephone call. Patients consenting to the telephone survey will be screened for eligibility for the study by trained interviewers. If eligible, patients will be asked to complete the baseline survey at the time of the call.

Patients triaged as either semi-urgent or non-urgent will be screened for eligibility. Eligible patients will be those who meet the following criteria:

Complaint of pain in the knee due to knee OA (as per referral) lasting longer than 3 months;

Aged 18 years or older;

Classified as overweight or obese with a self-reported BMI between ≥27 and <40 kg/m2;

Have access to and can use a telephone;

Knee pain from OA severe enough to cause at least average knee pain intensity of ≥3 of 10 on a 0–10 numerical rating scale (NRS) over the past week, or moderate level of interference in activities of daily living (adaptation of item 8 of the 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF36)38).

Patients will be excluded if they:

Have a known or suspected serious pathology as the underlying cause of their knee pain (eg, fracture, cancer, inflammatory arthritis such as rheumatoid arthritis, gout or infection);

Have a previous history of obesity surgery;

Are currently participating in any prescribed, medically supervised or commercial weight loss programme;

Have had knee surgery in the past 6 months, or planned surgery in the next 6 months;

Are unable to walk unaided;

Are unable to comply with the study protocol that requires them to, adapt meals or exercise, due to non-independent living arrangements;

Any medical or physical impairment, apart from knee pain, precluding safe participation in exercise such as uncontrolled hypertension, or morbid obesity (BMI>40);

Cannot speak or read English sufficiently to complete the study procedures.

Random allocation and blinding

Prior to randomisation, all patients are informed that the programme will involve regular phone calls/text messages to monitor their condition and any habits that affect their pain. Eligible patients from the cohort will be randomised to an intervention or a control group (1:1 ratio). The randomisation schedule will be generated a priori by an independent statistician using SAS V.9.3 through the SURVEYSELECT procedure. To randomise patients into the study, trained interviewers will open an opaque envelope containing the patient's group allocation while the patient is still on the telephone. Participants randomised to the intervention group will be informed that they can receive a clinical intervention now and those in the control group remain part of the cohort, but be told they will be offered clinical services in 6 months’ time. Envelopes will be prepared by a staff member independent from the study. Patient progress through the study is outlined in figure 1. Patients will be informed they can discontinue at any time without implications for orthopaedic care.

All outcome assessors will be blind to group allocation.

Intervention group

Intervention participants will receive advice and education about the benefits of weight loss and physical activity for their conditions by trained interviewers as part of the baseline telephone survey. Interviewers will then refer participants to the NSW Get Healthy Information and Coaching Service within 1–2 days after completing the baseline telephone survey (GHS; www.gethealthynsw.com.au).39 The referral to GHS will be provided to the service by the research team on the participants’ behalf. The GHS is an existing, free, population-wide telephone-based health coaching service provided by the NSW Government to support adults in NSW to make sustained healthy lifestyle improvements including diet, physical activity and achieving or maintaining a healthy weight.39 The GHS was launched in 2009 as part of the NSW response to the Australian Better Health Initiative.40 A pre-post study assessing the effectiveness of the GHS in the general population reported significant reductions in weight, BMI and waist circumference, and significant improvements in physical activity and nutrition-related behaviours, in those who completed the programme.39

The service consists of 10 individually tailored coaching calls delivered by university qualified health coaches, including dieticians, exercise physiologists, and physiotherapists, over a 6-month period.39 Participants will each be assigned a personal health coach to complete the 10 coaching calls. The support provided is based on national dietary and physical activity guidelines.41 42 Coaching calls are based on behaviour change and self-regulation principles and are designed to provide ongoing support using motivational interviewing principles, overcoming barriers, setting goals and making positive and sustainable lifestyle and behaviour changes.43 Coaching calls are provided on a tapered schedule, with a higher intensity of calls occurring in the first 12 weeks of the programme (6 calls) to guide, monitor and improve uptake, and the remaining calls to maintain adherence and avoid relapse.44 The frequency of the coaching calls is tailored to the participant's individual needs, with each call lasting between 10 and 15 min.39 Participants will also be posted printed support materials, including an information booklet and coaching journal. All participants will complete a short medical screening survey during their initial telephone call, and medical clearance from a GP will be obtained when required before commencing the programme as per existing service protocols.39

To ensure that the GHS health coaching is relevant for people with knee OA, health coaches will be provided training by a study investigator (CW) in evidence-based management recommendations for OA of the knee (2 h interactive training session) and provided with information resources to guide specific advice to be provided to study participants. The training session includes the topics of diagnosis, prognosis and evidence-based management strategies including the role of a healthy lifestyle and weight loss. The information provided is contained within international clinical practice guidelines for knee OA. Resources also detailed guideline-recommended advice about the nature of the condition, the diagnosis, prognosis and evidence-based treatments (ie, weight loss, exercise), as well as common misconceptions about OA and its management.

Control group

Participants allocated to the control group will continue on the usual care pathway and take part in data collection as part of the cohort study. Currently, no active management of knee OA patients waiting for an outpatient orthopaedic consultation is provided by the hospital; however, patients will be informed that a face-to-face appointment will be available in 6 months to determine the need for further care. Control group patients will also be asked to monitor their condition via phone calls during the 6 months.

Data collection procedures

Participants will be followed for 6 months and be asked to complete three self-reported questionnaires at baseline (pre-randomisation), week 6, and 26 weeks post-randomisation, to collect primary and secondary outcome data. All participants will be mailed a questionnaire 1 week prior to the 6-week and 26-week time point, and then asked to provide responses in one of two ways: via telephone or returned postal questionnaire. The baseline questionnaire will be completed via telephone only. Participants will also be asked to record the primary outcome ‘pain intensity’ at weeks 2, 10, 14, 18 and 22. Participants will be asked to provide this data via telephone or reply to text message, whichever their preference. During the 6-month telephone survey, participants will be asked to attend a face-to-face follow-up appointment (intervention group) or initial appointment (control group) with a health professional.

Measures

Baseline demographic characteristics

At baseline, participants will be asked demographic items including age, Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander status, employment status, country of origin, highest level of education, health insurance status, and current medical conditions. Length of time waiting for consultation (days) and triage classification will be obtained from hospital records.

Primary outcome: pain intensity

Participants will be asked to score their average knee pain intensity over the past week using a NRS of 0–10, where 0 represents ‘no pain’ and 10 represents ‘the worst possible pain’.45 Pain intensity will be collected at baseline, weeks 2, 6, 10, 14, 18, 22 and 26 post-randomisation (see table 1). The NRS is a valid and reliable measure of pain intensity in adults with OA.46

Table 1.

Trial measures

| Domain | Measurement | Time point (weeks) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary | ||

| Pain intensity | Average knee pain intensity over the past week using a numerical rating scale of 0–1045 46 | 0, 2, 6, 10, 14, 18, 22, 26 |

| Secondary | ||

| Disability and function | Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index47 | 0, 6, 26 |

| Subjective weight | Self-reported weight (kg) | 0, 6, 26 |

| Objective weight | Measured to the nearest 0.1 kg48 | 26 |

| Body mass index | Body mass index calculated as weight/height squared (kg/m2)49 | 0, 26 |

| Waist circumference | Measured to the nearest 0.1 cm48 | 26 |

| Quality of life | Short Form Health Survey V.250 | 0, 6, 26 |

| Perceived change in condition | Global Perceived Effect scale (−5 to 5 scale)51 | 6, 26 |

| Emotional distress | Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-2152 | 0, 26 |

| Sleep quality | Item 6 from the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index53 | 0, 6, 26 |

| Physical activity | The Active Australia Survey54 | 0, 6, 26 |

| Diet | Short food frequency questionnaire55 | 0, 6, 26 |

| Alcohol consumption | Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test56 | 0, 6, 26 |

| Smoking status | Self-reported current smoking status57 | 0, 6, 26 |

| Pain attitudes | Survey of Pain Attitudes58 | 0, 6, 26 |

| Fear avoidance beliefs | Fear Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire59 | 0, 26 |

| Health care usage | Medication use and healthcare used | 0, 6, 26 |

| Economic | Quality of life, healthcare usage, absenteeism (days off normal work due to knee pain in the past 6 weeks) | 0, 6, 26 |

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcomes include:

Physical function, measured using the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC);47

Self-reported weight (kg);

Objective weight (kg) measured to the nearest 0.1 kg by a trained research assistant using International Society for the Advancement of Kinanthropometry (ISAK) procedures;48

BMI calculated as weight/height squared (kg/m2);49

Waist circumference measured by a trained research assistant using ISAK procedures taken at the level of the narrowest point between the inferior rib border and the iliac crest using a flexible tape measure to the nearest 0.1 cm;48

Quality of life, measured using the 12-item Short Form Health Survey V.2 (SF12.v2);50

Global perceived change in symptoms, measured using the Global Perceived Effect scale (−5 to 5 scale);51

Emotional distress, measured using the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21;52

Sleep quality, measured using item 6 from the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index;53

Health behaviours: physical activity, measured using the Active Australia Survey,54 reported as the frequency and total minutes spent participating in physical activity; dietary intake, measured using a short food frequency questionnaire;55 alcohol consumption measured using the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test;56 and self-reported current smoking status;57

Attitudes and beliefs, measured using the Survey of Pain Attitudes;58 and the Fear Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire;59

Healthcare usage, including knee pain medication use (name and duration) and type of health service used for knee pain including number of sessions.

See table 1 for data collection time points for secondary outcomes.

Intervention and data integrity

The delivery of the intervention will be assessed using data provided by the GHS including commencement, the number, length and timing of coaching calls and achievement of identified goals. Patient-reported receipt of care (as well as additional care) will be collected at all time points. Participants will be monitored for adverse events throughout the intervention period. All adverse events will be recorded and serious adverse events will be assessed and managed on a case-by-case basis according to Good Clinical Practice guidelines.60 Trial data integrity will be monitored by regularly scrutinising data files for data omissions and errors. Manually entered data (ie, data not recorded directly by participant) will be double entered, and the source of any inconsistencies will be explored and resolved in consultation with the lead investigator (CW).

Sample size

Sample size was calculated using Stata sample size calculator. Using a SD of 2.7, a two-sided α of 0.025 (to account for multiple outcomes of interest—pain and weight),61 and allowing for 15% loss to follow-up, a sample of 60 participants per group will provide 90% power to detect a clinically meaningful difference of 2 in pain intensity (pain NRS) scores between intervention and control groups at 26 weeks. This sample also provides 80% power to detect a 6% weight reduction which is hypothesised to lead to a clinically meaningful reduction in pain.14 In these calculations, the increase in statistical power conferred by baseline covariates has been conservatively ignored.

Statistical analysis

The data will be analysed using an intention-to-treat principle, and by a statistician blinded to group allocation.

Primary outcome analysis

Between-group differences in pain intensity will be assessed using linear mixed models, with random intercepts for individuals to account for correlation of repeated measures. We will obtain estimates of the effect of the intervention and 95% CIs by constructing linear contrasts to compare the adjusted mean change in outcome from baseline to each time point between the treatment and control groups. Dummy coded variables representing group allocation will be used to ensure blinding of the analyses. Missing data will be assessed for randomness if this is more than 10%.

Secondary outcomes analysis

Linear mixed models will be used to assess treatment effect on secondary outcomes as per the primary outcome. We will compare the adjusted mean change (continuous variables) or difference in proportions (dichotomous variables) in outcome from baseline to each time point between the treatment and control groups.

An economic evaluation will also be undertaken. For this, data regarding patient quality of life, healthcare and community services, including estimated out-of-pocket cost, and work absenteeism will be collected over the duration of the study, see table 1 for details of these measures.

Conclusion

The present study has been designed to investigate the effectiveness of referral to a telephone-based weight management and healthy lifestyle programme to reduce pain and weight in overweight or obese patients with knee OA.

The study is a novel approach to integrating a telephone-based programme into the healthcare service delivered to patients with knee OA. The findings of this trial will determine if this more accessible model of care can be used as part of routine practice, and whether it has potential to change the management of many patients with knee OA who are referred for orthopaedic consultation.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Christopher Williams at @cmwillow

Contributors: KMO, CW, AW, JW, EC, LW and SY were responsible for the design of the study. CW and JW procured funding. All authors contributed to developing the intervention and data collection protocols and materials, and reviewing, editing, and approving the final version of the paper. KMO drafted the manuscript, and all authors have contributed to the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study is funded by Hunter New England Local Health District, and the Hunter Medical Research Institute. The project also received infrastructure support from the University of Newcastle.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The trial will be conducted in the Hunter New England region in NSW, Australia and has been approved by the Hunter New England Health Human Research Ethics Committee (13/12/11/5.18), and the University of Newcastle Human Research Ethics Committee (H-20-0043). The trial has been prospectively registered with the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12615000490572). The results will be disseminated in peer-reviewed journals and at scientific conferences.

Ethics approval: The Hunter New England Health Human Research Ethics Committee, and the University of Newcastle Human Research Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012;380:2197–223. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61689-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012;380:2163–96. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61729-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Felson DT, Lawrence RC, Dieppe PA et al. Osteoarthritis: new insights. Part 1: the disease and its risk factors. Ann Intern Med 2000;133:635–46. 10.7326/0003-4819-133-8-200010170-00016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2015;385:117–71. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Access Economics (Firm) & Diabetes Australia. The economic costs of obesity. Canberra, Australia: Diabetes Australia; Access Economics, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arthritis and Osteoporosis Victoria. A problem worth solving. Elsternwick: Arthritis and Osteoporosis Victoria, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 7.March ML, Bachmeier CJ. Economics of osteoarthritis: a global perspective. Baillieres Clin Rheumatol 1997;11:817–34. 10.1016/S0950-3579(97)80011-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson VL, Hunter DJ. The epidemiology of osteoarthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2014;28:5–15. 10.1016/j.berh.2014.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anandacoomarasamy A, Caterson I, Sambrook P et al. The impact of obesity on the musculoskeletal system. Int J Obes 2008;32:211–22. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blagojevic M, Jinks C, Jeffery A et al. Risk factors for onset of osteoarthritis of the knee in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2010;18:24–33. 10.1016/j.joca.2009.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Felson DT, Zhang Y. An update on the epidemiology of knee and hip osteoarthritis with a view to prevention. Arthritis Rheum 1998;41:1343–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sowers MR, Karvonen-Gutierrez CA. The evolving role of obesity in knee osteoarthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2010;22:533–7. 10.1097/BOR.0b013e32833b4682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bliddal H, Leeds AR, Stigsgaard L et al. Weight loss as treatment for knee osteoarthritis symptoms in obese patients: 1-year results from a randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:1798–803. 10.1136/ard.2010.142018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Christensen R, Bartels EM, Astrup A et al. Effect of weight reduction in obese patients diagnosed with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66:433–9. 10.1136/ard.2006.065904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Richmond J, Hunter D, Irrgang J et al. Treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee (nonarthroplasty). J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2009;17:591–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hochberg MC, Altman RD, April KT et al. American College of Rheumatology 2012 recommendations for the use of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies in osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res 2012;64:465–74. 10.1002/acr.21596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McAlindon TE, Bannuru RR, Sullivan MC et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2014;22:363–88. 10.1016/j.joca.2014.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Clinical Guideline Centre (NICE). Osteoarthritis: care and management in adults. London, UK: NICE, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP). Guideline for the non-surgical management of hip and knee osteoarthritis. Melbourne, VIC: RACGP, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bopf D, McAuliffe M, Shillington M et al. Knee osteoarthritis: use of investigations and nonoperative management in The Australian primary care setting. Australas Med J 2010;1:194–7. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brand C, Harrison C, Tropea J et al. Management of osteoarthritis in general practice in Australia. Arthritis Care Res 2014;66:551–8. 10.1002/acr.22197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haskins R, Henderson JM, Bogduk N. Health professional consultation and use of conservative management strategies in patients with knee or hip osteoarthritis awaiting orthopaedic consultation. Aust J Prim Health 2014;20:305–10. 10.1071/PY13064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hunter DJ. Lower extremity osteoarthritis management needs a paradigm shift. Br J Sports Med 2011;45:283–8. 10.1136/bjsm.2010.081117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.MacKay C, Davis AM, Mahomed N et al. Expanding roles in orthopaedic care: a comparison of physiotherapist and orthopaedic surgeon recommendations for triage. J Eval Clin Pract 2009;15:178–83. 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2008.00979.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shaw K, O'Rourke P, Del Mar C et al. Psychological interventions for overweight or obesity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;(2):CD003818 pub2 10.1002/14651858.CD003818.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Messier SP, Mihalko SL, Legault C et al. Effects of intensive diet and exercise on knee joint loads, inflammation, and clinical outcomes among overweight and obese adults with knee osteoarthritis: the IDEA randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2013;310:1263–73. 10.1001/jama.2013.277669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Appel LJ, Clark JM, Yeh HC et al. Comparative effectiveness of weight-loss interventions in clinical practice. N Engl J Med 2011;365:1959–68. 10.1056/NEJMoa1108660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.March L, Amatya B, Osborne RH et al. Developing a minimum standard of care for treating people with osteoarthritis of the hip and knee. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2010;24:121–45. 10.1016/j.berh.2009.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maisiak R, Austin J, Heck L. Health outcomes of two telephone interventions for patients with rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1996;39:1391–9. 10.1002/art.1780390818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eakin EG, Lawler SP, Vandelanotte C et al. Telephone interventions for physical activity and dietary behavior change: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med 2007;32:419–34. 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goode AD, Reeves MM, Eakin EG. Telephone-delivered interventions for physical activity and dietary behavior change: an updated systematic review. Am J Prev Med 2012;42:81–8. 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.08.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Allen KD, Oddone EZ, Coffman CJ et al. Telephone-based self-management of osteoarthritis: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2010;153:570–9. 10.7326/0003-4819-153-9-201011020-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Odole AC, Ojo OD. A Telephone-based physiotherapy intervention for patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. Int J Telerehabilitation 2013;5:11–20. 10.5195/ijt.2013.6125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weinberger M, Tierney WM, Booher P et al. Can the provision of information to patients with osteoarthritis improve functional status? A randomized, controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 1989;32:1577–83. 10.1002/anr.1780321212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Relton C, Torgerson D, O'Cathain A et al. Rethinking pragmatic randomised controlled trials: introducing the “cohort multiple randomised controlled trial” design. BMJ 2010;340:c1066 10.1136/bmj.c1066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chan AW, Tetzlaff JM, Altman DG et al. SPIRIT 2013 statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:200–7. 10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.MyHospitals.gov.au. About the data—Elective surgery waiting times. http://www.myhospitals.gov.au/about-the-data/elective-surgery-waiting-times (accessed 15 Sep 2015).

- 38.Ware J, Snow K, Kosinski M et al. SF-36 health survey: manual and interpretation guide. Boston, MA: The Health Institute, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 39.O'Hara BJ, Phongsavan P, Venugopal K et al. Effectiveness of Australia's Get Healthy Information and Coaching Service®: Translational research with population wide impact. Prev Med 2012;55:292–8. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.07.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Council of Australian Governments (COAG). COAG Communique: 10th February 2006. Canberra, Australia: Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 41.National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). Australian Dietary Guidelines. Canberra: NHMRC, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brown W, Bauman A, Bull F et al. Development of evidence-based physical activity recommendations for adults (18-64 years). Report prepared for the Australian Government Department of Health 2012.

- 43.Palmer S, Tubbs I, Whybrow W. Health coaching to facilitate the promotion of healthy behaviour and achievement of health-related goals. Int J Health Promot Educ 2003;41:91–3. 10.1080/14635240.2003.10806231 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Larimer ME, Palmer RS, Marlatt GA. Relapse prevention. An overview of Marlatt's cognitive-behavioral model. Alcohol Res Health 1999;23:151–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jensen MP, Turner JA, Romano JM et al. Comparative reliability and validity of chronic pain intensity measures. Pain 1999;83:157–62. 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00101-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hawker GA, Mian S, Kendzerska T et al. Measures of adult pain: Visual Analog Scale for Pain (VAS Pain), Numeric Rating Scale for Pain (NRS Pain), McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ), Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ), Chronic Pain Grade Scale (CPGS), Short Form-36 Bodily Pain Scale (SF-36 BPS), and Measure of Intermittent and Constant Osteoarthritis Pain (ICOAP). Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011;63(Suppl 11):S240–52. 10.1002/acr.20543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bellamy N. WOMAC user guide IX. Brisbane, QLD: Nicholas Bellamy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 48.International Society for the Advancement of Kinanthropometry (ISAK). International standards for anthropometric assessment. Underdale, SA: ISAK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 49.National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI), NHLBI Obesity Education Initiative et al. The practical guide: identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, 2000. NIH publication 00-4084 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Turner-Bowker DM et al. User's manual for the SF-12v2 health survey (with a supplement documenting SF-12 health survey). Boston, MA; Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric Incorporated, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kamper SJ, Ostelo RWJG, Knol DL et al. Global Perceived Effect scales provided reliable assessments of health transition in people with musculoskeletal disorders, but ratings are strongly influenced by current status. J Clin Epidemiol 2010;63:760–6.e1. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lovibond SH, Lovibond PF. Manual for the depression anxiety stress scales. 2nd edn Sydney, NSW: Psychology Foundation, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH et al. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res 1989;28:193–213. 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). The Active Australia Survey: a guide and manual for implementation, analysis and reporting. Cat. no. CVD 22. Canberra, Australia: AIHW, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Centre for Epidemiology and Research. NSW population health survey. Sydney, NSW: NSW Department of Health, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Babor T, Higgins-Biddle J, Saunders J et al. AUDIT: the alcohol use disorders identification test. Guidelines for use in primary care. 2nd edn Geneva: World Health Organization, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shiri R, Karppinen J, Leino-Arjas P et al. The association between smoking and low back pain: a meta-analysis. Am J Med 2010;123:87.e7–35. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.05.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jensen MP, Karoly P, Huger R. The development and preliminary validation of an instrument to assess patients’ attitudes toward pain. J Psychosom Res 1987;31:393–400. 10.1016/0022-3999(87)90060-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Waddell G, Newton M, Henderson I et al. A Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ) and the role of fear-avoidance beliefs in chronic low back pain and disability. Pain 1993;52:157–68. 10.1016/0304-3959(93)90127-B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Department of Health and Ageing Therapeutic Goods Administration. The Australian clinical trial handbook: a simple, practical guide to the conduct of clinical trials to international standards of good clinical practice (GCP) in The Australian context. Canberra, Australia: Commonwealth of Australia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Proschan MA, Waclawiw MA. Practical guidelines for multiplicity adjustment in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 2000;21: 527–39. 10.1016/S0197-2456(00)00106-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]