Abstract

Objectives

This study investigated the association between employment status and depression.

Methods

Data from the Korea Welfare Panel Study (KOWEPS) collected from 2008 to 2011 were used. A total of 7368 subjects were included in this study after exclusion of subjects with missing data and those who were self-employed or could not work. Depression was assessed using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). Employment status, age, sex, region, education, marital status, income, head of household, self-rated health, smoking status, drinking habits, and the current year's and the previous year's CES-D scores were included in the model as independent variables. A generalised linear mixed-effects model for longitudinal binary data was used.

Results

Compared with those who were permanently employed, individuals who moved from permanent to precarious employment (OR 1.45, 95% CI 1.23 to 1.70) or to unemployment (OR 1.78, 95% CI 1.30 to 2.43) and from precarious employment to unemployment (OR 1.65, 95% CI 1.32 to 2.06) showed a significantly increased the odds of having depression. Continuing precarious employment (OR 1.54, 95% CI 1.30 to 1.83) or unemployment (OR 1.45, 95% CI 1.23 to 1.70) also significantly increased the odds of having depression. These results were particularly identified in men and head of household women. The effects were not significant among non-head of household women.

Conclusions

Precarious employment and unemployment were clearly associated with having depression. In addition, in view of our findings, policy makers should consider sex and head of household status when developing welfare policies. The inequity between precarious jobs and permanent jobs should be tackled.

Keywords: depression, job status, Asian

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A negative change in employment status as well as continuing precarious employment or unemployment are associated with having depression.

The strengths of this study are its ability to identify association by using 5-year longitudinal data and, because the Korea Welfare Panel Study relies on a national sample, the results can be generalised to the Korean population as a whole.

These results were most pronounced in men, and in head of household women, while non-head of household women were not affected by employment status.

To reduce the impact of the healthy-worker effect, we excluded subjects who reported that they were ‘not able to work’, but this effect may have nonetheless influenced our results.

It was not possible to classify the types of precarious employment in detail, and we unable to determine whether unemployment was voluntary.

Introduction

For more than a decade, globalisation, international competition and the use of skill-based technology have caused structural changes1 that have led to changes in the labour market.2 Specifically, the complexity of work arrangements, including the use of contract and temporary workers, has increased, leading to reduced job security.3 4 Temporary employment and other flexible or atypical work arrangements may have beneficial as well as adverse effects.5 Some people prefer atypical work in order to make the best use of their time.

However, income insecurity and the risk associated with seasonal employment also cause various adverse effects. Several studies have reported that precarious employment, changes in employment status, and unemployment had negative influence on health.6–8 Employment status is a key factor affecting socioeconomic status which in turn is associated with health outcome.9 Temporary employment has an adverse effect on mental health due to employment instability and the poor quality of temporary jobs. Indeed, unstable work often involves undesirable jobs and/or low wages.10 Additionally, the health effects of precarious employment may depend on the degree of instability.11 Unemployment status was related to psychological status such as anxiety, depression and lowered health outcomes due to job loss.12

In Korea, the precarious employment rate has increased and job security has decreased over recent years. The labour market was severely affected by the economic crisis of 1997–1998, which was caused by a current account deficit, inadequate corporation cash flows, weakening bank finances and low international reserves.13 The Korean government was rescued by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) which imposed an austerity plan. Most of the financial institutions were restructured, research and development costs and the investment ratio were reduced, and 66.9% of corporations were restructured by the IMF. Under the IMF plan, the Korean government had to improve the flexibility of the labour market, so that corporations could fire workers more easily than before, and the number of temporary workers and work hours increased.14 Some 58% of Korean workers were permanently employed in 1992–1996, but this fell to below 48% in 2000. The temporary employment rate has gradually increased since the economic crisis of 1997, by 24.4% from 2003 to 2013.15 In 2011, it was 27.1%, second only to Chile among OECD countries.

It was a complicated situation for female employees: 70% of female employees were irregularly employed in 2000, compared to 57% in 1995.16 Ma's study17 showed that the economic crisis affected Korean women's return to work after childbirth and their career prospects. In an unstable economic environment, women who are married or have children are usually encouraged to work.18 Also globalisation has pushed employers to replace low-skilled workers with workers from low-wage economies. There were almost 1 114 000 foreign workers in Korea in 2012, revealing that the impact of globalisation was disadvantageous for temporary workers. There is public concern that globalisation exacerbates inequality.19 Even after the economic crisis, the Korean labour market has become vulnerable to the worldwide economy due to weak domestic consumption and a high level of dependence on exports. In the context of the growth of skill-based technologies and globalisation, traditional labour market mechanisms did not operate in Korea, creating the need for flexibility in the labour market. The atypical employment ratio has been increasing due to the strong legal protection in place for permanent employees.5 20

This Korean labour market situation may affect mental health and thereby contribute to the increasing rate of suicide, one of the major problems currently facing the Korean healthcare system. Indeed, the suicide rate in Korea is the highest among OECD countries,21 having increased from 10.2 per 100 000 in 1985 to 31.2 per 100 000 in 2010.22

Therefore, our study objective was to assess the effects of employment status on mental health, particularly depression. We hypothesised that unstable employment, such as precarious employment and unemployment, would have more negative effects on mental health than permanent employment.

Methods

Study population

This study analysed data from the Korea Welfare Panel Study (KOWEPS) collected from 2008 to 2012. The data from KOWEPS, an ongoing longitudinal study that produces nationally representative data, are published annually. KOWEPS started in 2006 with 18 856 Korean participants from 7072 households,23 with a follow-up rate of 73.6% in 2012 compared to households in 2006.

In our study, data (N=9336) from 2009 were considered the baseline data. Data in 2008 were included as lagged data in the baseline data. Subjects who were self-employed (N=1299), unable to work (N=1996), under 18 years of age (N=2) or disabled (N=1321) were excluded. Those with missing variables (N=669) were then excluded to give a final total of 7368 included subjects. Ethical approval was not required as KOWEPS provides secondary data that are publicly available for scientific use and do not contain private information.

Variables

The dependent variable in this study was depression, which we evaluated with the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D).24 25 KOWEPS used a 11-item self-report questionnaire which is comparable with the 20-item CES-D.26 In this study, the 11-item CES-D score was multiplied by 20/11. CES-D scores range from 0 to 60, with a score above 16 usually indicating depressive symptoms.27 28 The CES-D has good sensitivity and specificity and high internal consistency for identifying risk of depression.29

Changes in employment status, the primary independent variable, were measured in terms of three categories: permanent employment, precarious employment and unemployment. Precarious employment was defined as employment with a work contract for part-time work, indirect employment, employment with a work contract of limited duration, or employment with a terminable or unsustainable contract. Permanent employment was defined as direct full-time employment with no fixed term and a sustainable contract. In this study, the definition of unemployed included all subjects who were without work regardless of whether they were looking for work or not.

Age, sex, region, education, marital status, income, head of household, self-rated health, smoking status, Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) score and year were used as covariates. These are known risk factors for depression.30 31 Region was divided into Seoul, metropolitan, city and rural areas. Education was categorised into four groups: elementary school or less, middle school, high school, and university or more. Marital status was categorised as single, divorced or separated, widowed and married. Co-habiting outside marriage is unusual in South Korean culture, and so was not considered in our study. Income was analysed in quartiles, and head of household was included to distinguish whether a subject was the actual breadwinner or not. Self-rated health was categorised into very bad or bad, average, good and very good. We combined very bad and bad because of the small number of subjects in the former category. Smoking status was categorised into never, past and current. AUDIT scores were categorised into 0–7, 8–15 and 16 or over.32

Statistical analysis

Student’s t tests and χ2 tests were used to analyse the relationship of general characteristics and employment status with depression score at baseline. A generalised linear mixed-effects model with a logit link function, random intercept for longitudinal binary data was used to identify the association between employment change and depression status. The regression equation was logit(depressionit)=intercept+β1▵employment_statusit+β2CES-Dit−1+β3Xit, where depressionit is the dependent variable during time period t for participant i, Xit represents covariates, and ▵employment_statusit represents change in employment status from previous year to current year for that participant, which included nine categorical variables: permanent→, precarious→permanent, permanent→precarious, precarious→, unemployed→precarious, unemployed→permanent, unemployed→, precarious→unemployed and permanent→unemployed. We added the scores on the CES-Dit−1 to control for the previous year's CES-D scores. Subgroup analyses for sex and head of household were conducted. All analyses were performed using SAS program V.9.4 (Cary, North Carolina, USA), and PROC GLIMMIX was used to fit a generalised linear mixed-effects model for longitudinal binary data.

Results

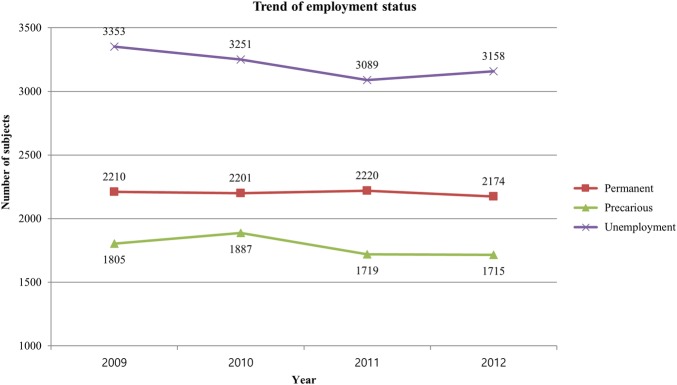

Table 1 presents the general characteristics of study participants at baseline by employment status. There were statistically significant differences in the distribution of all general characteristics among subjects who were permanently employed, precariously employed and unemployed at baseline. Depressive symptoms were most prevalent in the unemployed group, followed by the precariously employed group; depressive symptoms were least prevalent among those who were permanently employed. Figure 1 illustrates trends in employment status and shows that the rate of precarious employment has decreased over time. A total of 1805 subjects were precariously employed in 2009 compared to 1715 in 2012.

Table 1.

General characteristics of study participants at baseline (2009) (n=7368)

| Permanent employment (n=2210) | Precarious employment (n=1805) | Unemployment (n=3353) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | p Value | |

| Age (years) | <0.001 | |||

| ≤24 | 42 (9.1) | 112 (24.3) | 307 (66.6) | |

| 25–34 | 646 (42.0) | 313 (20.4) | 579 (37.6) | |

| 35–44 | 847 (43.9) | 450 (23.3) | 634 (32.8) | |

| 45–54 | 466 (33.8) | 450 (32.6) | 464 (33.6) | |

| ≥55 | 209 (10.2) | 480 (23.3) | 1369 (66.5) | |

| Sex | <0.001 | |||

| Men | 1461 (47.1) | 799 (25.7) | 843 (27.2) | |

| Women | 749 (17.6) | 1006 (23.6) | 2510 (58.9) | |

| Region | <0.001 | |||

| Rural | 281 (21.2) | 226 (17.0) | 819 (61.8) | |

| City | 830 (33.4) | 597 (24.0) | 1059 (42.6) | |

| Metropolitan | 622 (29.4) | 578 (27.3) | 916 (43.3) | |

| Seoul | 477 (33.1) | 404 (28.1) | 559 (38.8) | |

| Education | <0.001 | |||

| College | 1247 (43.8) | 517 (18.2) | 1084 (38.1) | |

| High school | 769 (30.3) | 736 (29.0) | 1037 (40.8) | |

| Middle school | 113 (15.4) | 252 (34.2) | 371 (50.4) | |

| Elementary | 81 (6.5) | 300 (24.2) | 861 (69.3) | |

| Marital status | <0.001 | |||

| Married | 1558 (31.4) | 1109 (22.4) | 2292 (46.2) | |

| Bereaved | 72 (23.6) | 144 (47.2) | 89 (29.2) | |

| Divorced or separated | 42 (9.0) | 132 (28.3) | 293 (62.7) | |

| Single | 538 (32.9) | 420 (25.7) | 679 (41.5) | |

| Income | <0.001 | |||

| Q1 (high) | 1083 (45.6) | 430 (18.1) | 860 (36.2) | |

| Q2 | 750 (33.4) | 602 (26.8) | 893 (39.8) | |

| Q3 | 336 (18.7) | 555 (30.9) | 906 (50.4) | |

| Q4 (low) | 41 (4.3) | 218 (22.9) | 694 (72.8) | |

| Head of household | <0.001 | |||

| No | 870 (19.4) | 950 (21.2) | 2659 (59.4) | |

| Yes | 1140 (42.4) | 855 (31.8) | 694 (25.8) | |

| Self-rated health | <0.001 | |||

| Very good | 616 (41.4) | 328 (22.1) | 543 (36.5) | |

| Good | 1254 (33.0) | 962 (25.3) | 1580 (41.6) | |

| Normal | 272 (19.6) | 352 (25.4) | 761 (54.9) | |

| Bad and very bad | 68 (9.7) | 163 (23.3) | 469 (67.0) | |

| Smoking | <0.001 | |||

| Never | 1104 (22.6) | 1112 (22.8) | 2669 (54.6) | |

| Past | 376 (43.8) | 213 (24.8) | 269 (31.4) | |

| Current | 730 (44.9) | 480 (29.5) | 415 (25.5) | |

| AUDIT score | <0.001 | |||

| 0–7 | 1355 (24.3) | 1297 (23.2) | 2927 (52.5) | |

| 8–15 | 616 (46.6) | 368 (27.8) | 338 (25.6) | |

| ≥16 | 239 (51.2) | 140 (30.0) | 88 (18.8) | |

| Depression (depressive symptoms) | <0.001 | |||

| No | 2005 (32.0) | 1493 (23.9) | 2761 (44.1) | |

| Yes | 205 (18.5) | 312 (28.1) | 592 (53.4) | |

| Total | 2210 (30.0) | 1805 (24.5) | 3353 (45.5) |

p Values were obtained from χ2 tests.

AUDIT, Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test.

Figure 1.

Trend of employment status (2009–2012).

Table 2 presents the results of the generalised linear mixed-effects model, which showed that the odds of having depression was increased among those whose employment status changed to unemployed or precarious. After adjusting all covariates, the permanent→unemployed (OR 1.78, 95% CI 1.30 to 2.43) and precarious→unemployed (OR 1.65, 95% CI 1.32 to 2.06) groups had the highest ORs for depressive symptoms compared to those who retained their permanent employment status. The odds of having depression was increased in those whose employment status became worse, and also in those who remained precariously employed or unemployed compared to those who remained permanently employed. Continuing precarious employment (OR 1.54, 95% CI 1.30 to 1.83) and moving from unemployment to precarious employment (OR 1.34, 95% CI 1.07 to 1.68) also increased the odds of having depression compared to continuing permanent employment. Subjects who transitioned to permanent employment had the same odds of having depression as those with uninterrupted permanent employment. Furthermore, subjects who were female, lived in a city or metropolitan area, had a lower educational level, were unmarried, had a lower household income, had bad self-rated health status, were a current smoker, and had a high AUDIT score were more likely to have depression symptoms.

Table 2.

The association between employment status change and depression

| Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| ≤24 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 25–34 | 0.90 (0.73 to 1.11) | 1.01 (0.78 to 1.29) |

| 35–44 | 0.84 (0.68 to 1.03) | 0.87 (0.66 to 1.15) |

| 45–54 | 1.24 (1.01 to 1.52) | 0.91 (0.68 to 1.22) |

| ≥55 | 2.08 (1.72 to 2.52) | 0.70 (0.52 to 0.96) |

| Sex | ||

| Men | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Women | 1.80 (1.64 to 1.97) | 1.83 (1.56 to 2.15) |

| Region | ||

| Rural | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| City | 0.81 (0.72 to 0.91) | 1.13 (0.99 to 1.29) |

| Metropolitan | 0.82 (0.72 to 0.93) | 1.13 (0.99 to 1.30) |

| Seoul | 0.87 (0.76 to 0.99) | 1.29 (1.11 to 1.50) |

| Education | ||

| College | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| High school | 1.66 (1.48 to 1.86) | 1.15 (1.01 to 1.30) |

| Middle school | 2.49 (2.15 to 2.89) | 1.21 (1.01 to 1.46) |

| Elementary | 4.04 (3.59 to 4.54) | 1.25 (1.04 to 1.50) |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Bereaved | 3.53 (2.99 to 4.18) | 1.71 (1.42 to 2.07) |

| Divorced or separated | 3.48 (3.06 to 3.97) | 1.31 (1.10 to 1.55) |

| Single | 1.02 (0.91 to 1.14) | 1.28 (1.08 to 1.52) |

| Income | ||

| Q1 (high) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Q2 | 1.50 (1.32 to 1.70) | 1.21 (1.06 to 1.39) |

| Q3 | 2.81 (2.49 to 3.17) | 1.69 (1.47 to 1.94) |

| Q4 (low) | 5.80 (5.11 to 6.58) | 2.24 (1.90 to 2.65) |

| Head of household | ||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 1.28 (1.17 to 1.39) | 1.05 (0.91 to 1.21) |

| Self-rated health | ||

| Very good | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Good | 1.19 (1.05 to 1.35) | 1.11 (0.97 to 1.28) |

| Normal | 2.67 (2.32 to 3.06) | 1.89 (1.60 to 2.23) |

| Bad and very bad | 6.35 (5.50 to 7.32) | 3.60 (3.02 to 4.29) |

| Smoking | ||

| Never | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Past | 0.73 (0.66 to 0.80) | 1.01 (0.85 to 1.20) |

| Current | 0.95 (0.86 to 1.06) | 1.37 (1.15 to 1.63) |

| AUDIT score | ||

| 0–7 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 8–15 | 0.83 (0.74 to 0.94) | 1.34 (1.17 to 1.55) |

| ≥16 | 1.62 (1.38 to 1.91) | 2.19 (1.80 to 2.67) |

| Year | ||

| 2009 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 2010 | 0.65 (0.59 to 0.71) | 0.58 (0.52 to 0.66) |

| 2011 | 0.63 (0.57 to 0.70) | 0.66 (0.59 to 0.74) |

| 2012 | 0.55 (0.50 to 0.61) | 0.61 (0.51 to 0.72) |

| Employment status | ||

| Permanent→permanent | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Precarious→precarious | 2.86 (2.43 to 3.36) | 1.54 (1.30 to 1.83) |

| Unemployment→unemployment | 2.91 (2.53 to 3.35) | 1.45 (1.23 to 1.70) |

| Precarious→permanent | 1.68 (1.32 to 2.14) | 1.22 (0.95 to 1.56) |

| Unemployment→permanent | 1.50 (1.04 to 2.16) | 1.05 (0.71 to 1.53) |

| Unemployment→precarious | 2.60 (2.11 to 3.21) | 1.34 (1.07 to 1.68) |

| Permanent→precarious | 2.17 (1.73 to 2.73) | 1.46 (1.16 to 1.85) |

| Permanent→unemployment | 2.83 (2.09 to 3.83) | 1.78 (1.30 to 2.43) |

| Precarious→unemployment | 3.76 (3.07 to 4.62) | 1.65 (1.32 to 2.06) |

| Lag(CES-D) | 1.09 (1.09 to 1.10) | 1.07 (1.06 to 1.07) |

Estimates were obtained from a generalised linear mixed-effects model with random subject effects.

AUDIT, Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test;

CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale.

Table 3 presents the results of the subgroup analyses. While there was a general trend for those whose employment status changed to precarious and unemployment to have a higher risk of experiencing depressive symptoms, the magnitude and significance of the effect differed by sex and head of household. The results of changing to unstable employment status or remaining in unstable employment was more apparent in men than in women, and in head of households than in non-head of households. Interestingly, men who were not head of household were more likely to experience depression when they moved from unemployment to unemployment (OR 2.65; 95% CI 1.29 to 5.45). Subjects with continuous precarious employment or unemployment status and moving from precarious employment to unemployment were likely to have depressive symptoms. The effects of employment status change on depression among head of household men were not significantly different when employment status improved compared to those who remained permanently employed, but were significantly associated with worsening employment status or continuing precarious employment or unemployment. The move from permanent employment to unemployment had the highest OR for depressive symptoms (OR 2.56, 95% CI 1.48 to 4.41). Among non-head of household women, employment status was not associated with the risk of experiencing depression. However, the risk among head of household women was greater than among head of household men.

Table 3.

The association between employment status change and depression by sex and head of household*

| Men |

Women |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-head of household | Head of household | Non-head of household | Head of household | |

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Permanent→permanent | 1.00 (0.99 to 2.14 | 1.00 (0.99 to 2.14) | 1.00 (0.99 to 2.14) | 1.00 (0.99 to 2.14) |

| Precarious→precarious | 2.36 (1.26 to 4.45) | 1.47 (1.09 to 2.00) | 1.26 (0.97 to 1.65) | 2.07 (1.28 to 3.36) |

| Unemployment→unemployment | 1.84 (1.02 to 3.32) | 1.72 (1.21 to 2.45) | 1.03 (0.81 to 1.30) | 2.71 (1.63 to 4.51) |

| Precarious→permanent | 0.72 (0.23 to 2.28) | 1.45 (0.96 to 2.18) | 0.94 (0.64 to 1.40) | 1.52 (0.78 to 2.97) |

| Unemployment→permanent | 2.25 (0.94 to 5.39) | 1.00 (0.43 to 2.36) | 0.71 (0.40 to 1.25) | 1.02 (0.33 to 3.12) |

| Unemployment→precarious | 2.65 (1.29 to 5.45) | 1.22 (0.74 to 2.02) | 0.93 (0.66 to 1.29) | 2.04 (1.12 to 3.69) |

| Permanent→precarious | 1.16 (0.45 to 2.97) | 1.73 (1.18 to 2.54) | 1.06 (0.72 to 1.55) | 2.05 (1.10 to 3.83) |

| Permanent→unemployment | 1.63 (0.55 to 4.80) | 2.56 (1.48 to 4.41) | 1.04 (0.62 to 1.73) | 3.10 (1.38 to 6.97) |

| Precarious→unemployment | 2.33 (1.11 to 4.91) | 1.64 (1.05 to 2.58) | 1.39 (0.99 to 1.95) | 1.83 (1.02 to 3.30) |

*Age, sex, marital status, region, education, income, self-rated health, smoking, AUDIT, lag(CES-D) and year variables were adjusted.

AUDIT, Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale.

Discussion

Our findings revealed that a negative change in employment status as well as continuing precarious employment or unemployment can cause depression. These effects were more pronounced in men and in head of household women.

As KOWEPS examines employment status and depression using CES-D, several reports have identified the effects of employment status and depression using KOWEPS data.33–35 Kim et al33 found that changing from precarious to permanent work or from permanent to precarious work was associated with new-onset depressive symptoms among Korean women. Another previous study by Kim et al34 identified an association between becoming employed after unemployment and depressive symptoms. Jang et al's35 study also showed that employment change is associated with risk of new-onset depressive symptoms, and that the association depends on sex and head of household status. These studies examined participants who were waged workers or had short-term follow-up data. Our study reported the effects of employment status change on depression and included unemployed subjects and the comprehensive employment status change variable.

Our results are consistent with the findings of many previous studies showing the relationship between precarious employment and depression.8 10 11 Similar to the situation in the USA and the EU,10 atypical jobs in Korea are often undesirable. According to a report issued by the Korean Ministry of Employment and Labor, the wages of temporary employees were only 63.6% of those of permanent employees in 2012, and temporary employees wanted to have permanent jobs.36

Many studies have examined the effect of job loss on mental health.7 37–39 Paul and Moser37 reported that an unemployed person does not have access to the five latent functions of employment: structured time, social contact, collective purpose, status and activity. The absence of these factors causes depression. Job loss also affects heath, as stress is caused by the anticipation of termination, the termination process, unemployment, and the job search.40 Specifically, the effect of job loss was a better predictor of depression than the effect of continuing unemployment.

Our results showed that employment status did not affect the risk for depression among non-head of household women. They did not report depressive symptoms despite having lost their jobs, moving to precarious from permanent employment or continuing in unemployment. This result may be due to Korean women's interrupted careers. Although women are highly educated or skilled, many women voluntarily resign or change to precarious jobs because of gender roles related to marriage or having children. Although women with children are willing to work, relatives and family encouraged them to leave their jobs.41 Our finding is consistent with a previous study showing that job loss was less threatening to the mental health of women than of men.42

Women are not as active as men in the Korean labour market; 58.5% of all female employees in Korea were permanent workers in 2012 compared to 72.7% of men. The employee-to-population ratio of Korean women aged 15–64 years was 53.1% in 2011,15 which is low compared with the OECD average of 59.7%.43 In 2010, 54.5% of Korean women aged 15–64 years participated in the labour force,43 while the OECD average was 61.8%. The rate of participation among women in the labour force is lower than in Korea in four countries: Turkey, Mexico, Italy and Chile. However, the results of employment status change differ according to head of household status. Both men and women who are the family breadwinners become depressed when their employment status worsens.44 45 The strongest association in our study was among head of household women, who have many sources of stress. According to the study of Kim et al33, such women usually have domestic in addition to patriarchal social responsibilities. Other reasons were related to economic problems arising from single-parenthood and bankruptcy.46

Moving from unemployment to precarious employment worsens the mental health of non-head of household men. This indicates it is difficult in Korea to move from a precarious job into permanent employment. The 1-year transition probability from precarious to permanent employment in Korea was only 11.1%, while the 3-year transition probability was 22.4%.47 As it is more difficult to improve one's employment status in Korea than in 15 other OECD countries, many people seeking employment try to get a permanent, secure job.

This study has several limitations. First, to reduce the impact of the healthy-worker effect, we excluded subjects who reported that they were ‘not able to work’, but this effect may have nonetheless influenced our results. Second, it was impossible to classify the types of precarious employment in detail, and we could not determine whether unemployment or precarious employment was voluntary. So we added the head of household variable as a proxy variable to identify whether employment status was voluntary or not. Third, all data were gathered from self-report surveys, so data potentially included recall bias. The strength of this study is its ability to identify associations by using 5-year longitudinal data. Additionally, because the KOWEPS relies on a national sample, the results can be generalised to the Korean population as a whole.

Our results suggest that negative changes in employment status, continuing precarious employment and unemployment increase the risk for depressive symptoms. These effects were clearly identified in men and in head of household women. In view of these differences, policymakers should consider sex and head of household status in determining welfare policies. The inequity between precarious jobs and permanent jobs should be reduced as regards job security and wages,. For head of household women, opportunities for education will improve their chances of getting a job.

The comprehensive effects of employment status, including differences in employment-related motivation, on health outcomes and self-rated health in different types of industry need to be investigated in further studies.

Footnotes

Contributors: K-BY analysed the data and drafted the manuscript. E-CP and SP contributed to the research design and interpretation of results. JAK and SJK contributed to data acquisition and data management. K-hC, J-WC and J-HK contributed to data analysis methods and data management. S-YJ helped revise the final draft.

Funding: None.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Raw data are available from https://www.koweps.re.kr:442/eng/main.do or the corresponding author at soheepark@yuhs.ac. Information on data management and statistical coding is available from the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Acemoglu D. Technical change, inequality, and the labor market. J Econ Lit 2002;40:7–72. 10.1257/jel.40.1.7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gebel M, Giesecke J. Labor market flexibility and inequality: the changing skill-based temporary employment and unemployment risks in Europe. Soc Forces 2011;90:17–39. 10.1093/sf/90.1.17 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Quesnel-Vallée A, DeHaney S, Ciampi A. Temporary work and depressive symptoms: a propensity score analysis. Soc Sci Med 2010;70:1982–7. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.02.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodriguez E. Marginal employment and health in Britain and Germany: does unstable employment predict health? Soc Sci Med 2002;55:963–79. 10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00234-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grubb D, Lee J, Tergeist P. Addressing Labour Market Duality in Korea, 2007OECD Social, Employment and Migration working papers No. 61. OECD. http://www.oecd.org/korea/39451179.pdf

- 6.Hammarström A, Virtanen P, Janlert U. Are the health consequences of temporary employment worse among low educated than among high educated? Eur J Public Health 2011;21:756–61. 10.1093/eurpub/ckq135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burgard SA, Brand JE, House JS. Toward a better estimation of the effect of job loss on health. J Health Soc Behav 2007;48:369–84. 10.1177/002214650704800403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Virtanen P, Janlert U, Hammarström A. Exposure to temporary employment and job insecurity: a longitudinal study of the health effects. Occup Environ Med 2011;68:570–4. 10.1136/oem.2010.054890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prus SG. Comparing social determinants of self-rated health across the United States and Canada. Soc Sci Med 2011;73:50–9. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Virtanen M, Kivimäki M, Joensuu M et al. Temporary employment and health: a review. Int J Epidemiol 2005;34:610–22. 10.1093/ije/dyi024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Virtanen P, Liukkonen V, Vahtera J et al. Health inequalities in the workforce: the labour market core-periphery structure. Int J Epidemiol 2003;32:1015–21. 10.1093/ije/dyg319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McKee-Ryan F, Song Z, Wanberg CR et al. Psychological and physical well-being during unemployment: a meta-analytic study. J Appl Psychol 2005;90:53–76. 10.1037/0021-9010.90.1.53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kwack SY. Factors contributing to the financial crisis in Korea. J Asian Econ 1998;9:611–25. 10.1016/S1049-0078(98)90066-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mah JS. Economic restructuring in post-crisis Korea. J Socio Econ 2006;35:682–90. 10.1016/j.socec.2005.11.031 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Statistics Korea. Economically active population, 2013. http://kosis.kr/ups/ups_01List01.jsp?grp_no=&pubcode=WA

- 16.Crotty J, Lee K. A political-economic analysis of the failure of neo-liberal restructuring in post-crisis Korea. Camb J Econ 2002;26:667–78. 10.1093/cje/26.5.667 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ma L. Economic crisis and women's labor force return after childbirth: evidence from South Korea. DemRes 2014;31:511–52. 10.4054/DemRes.2014.31.18 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pettit B, Hook J. The structure of women's employment in comparative perspective. Soc Forces 2005;84:779–801. 10.1353/sof.2006.0029 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee H, Lee J. The impact of offshoring on temporary workers: evidence on wages from South Korea. Rev World Econ 2015;151:555–87. 10.1007/s10290-015-0215-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones RS, Tsutsumi M. Sustaining Growth in Korea by Reforming the Labour Market and Improving the Education System, 2009 OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 672, OECD Publishing, Paris. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/226580861153

- 21.OECD. OECD family database-OECD Health data. Paris: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim SY, Kim MH, Kawachi I et al. Comparative epidemiology of suicide in South Korea and Japan: effects of age, gender and suicide methods. Crisis 2011;32:5–14. 10.1027/0227-5910/a000046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Department of Social Welfare SNU, Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs. KOWEPS User's Guide for Sixth and Seventh Year. Korea Wellfare Panel Study, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gellis ZD. Assessment of a brief CES-D measure for depression in homebound medically ill older adults. J Gerontol Soc Work 2010;53:289–303. 10.1080/01634371003741417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Randolf LS. The CESD-D scale: a self-report major depressive disorder scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas 1977;1:305–401. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kohout FJ, Berkman LF, Evans DA et al. Two shorter forms of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression) depression symptoms index. J Aging Health 1993;5:179–93. 10.1177/089826439300500202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pandya R, Metz L, Patten SB. Predictive value of the CES-D in detecting depression among candidates for disease-modifying multiple sclerosis treatment. Psychosomatics 2005;46:131–4. 10.1176/appi.psy.46.2.131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weissman MM, Sholomskas D, Pottenger M et al. Assessing depressive symptoms in five psychiatric populations: a validation study. Am J Epidemiol 1977;106:203–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Roberts RE et al. Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) as a screening instrument for depression among community-residing older adults. Psychol Aging 1997;12:277–87. 10.1037/0882-7974.12.2.277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Everson SA, Maty SC, Lynch JW et al. Epidemiologic evidence for the relation between socioeconomic status and depression, obesity, and diabetes. J Psychosom Res 2002;53:891–5. 10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00303-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cole MG, Dendukuri N. Risk factors for depression among elderly community subjects: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry 2003;160:1147–56. 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.6.1147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Donovan DM, Kivlahan DR, Doyle SR et al. Concurrent validity of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) and AUDIT zones in defining levels of severity among out-patients with alcohol dependence in the COMBINE study. Addiction 2006;101:1696–704. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01606.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim SS, Subramanian S, Sorensen G et al. Association between change in employment status and new-onset depressive symptoms in South Korea—a gender analysis. Scand J Work Environ Health 2012;38:537–45. 10.5271/sjweh.3286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim SS, Muntaner C, Kim H et al. Gain of employment and depressive symptoms among previously unemployed workers: a longitudinal cohort study in South Korea. Am J Ind Med 2013;56:1245–50. 10.1002/ajim.22201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jang SY, Jang SI, Bae HC et al. Precarious employment and new-onset severe depressive symptoms: a population-based prospective study in South Korea. Scand J Work Environ Health 2015;41:329–37. 10.5271/sjweh.3498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ministry of Employment and Labor. Survey Report on Labor Conditions by Employment Type. Seoul: Labor Market Analysis Division, Employment Policy Bureau, Ministry of Employment and Labor, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paul KI, Moser K. Unemployment impairs mental health: meta-analyses. J Vocational Behav 2009;74:264–82. 10.1016/j.jvb.2009.01.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berchick ER, Gallo WT, Maralani V et al. Inequality and the association between involuntary job loss and depressive symptoms. Soc Sci Med 2012;75:1891–4. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.07.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Park S, Cho SI, Jang SN. Health conditions sensitive to retirement and job loss among Korean middle-aged and older adults. J Prev Med Public Health 2012;45:188–95. 10.3961/jpmph.2012.45.3.188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Deb P, Gallo WT, Ayyagari P et al. The effect of job loss on overweight and drinking. J Health Econ 2011;30:317–27. 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2010.12.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Um K, Yang S. A qualitative study on the career interrupted and the child care of married women. J Korean Home Manag Assoc 2010;29:21–40. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jeon GS, Jang SN, Rhee SJ et al. Gender differences in correlates of mental health among elderly Koreans. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2007;62:S323–9. 10.1093/geronb/62.5.S323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.OECD. OECD Employment Database. Paris: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Prince MJ, Beekman AT, Deeg DJ et al. Depression symptoms in late life assessed using the EURO-D scale. Effect of age, gender and marital status in 14 European centres. Br J Psychiatry 1999;174:339–45. 10.1192/bjp.174.4.339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jacobs S, Hansen F, Berkman L et al. Depressions of bereavement. Compr Psychiatry 1989;30:218–24. 10.1016/0010-440X(89)90041-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee H, Han K, Jeon G. Impact on quality of life of single-parent female head of household economic stress. J Korea Contents Assoc 2013;13:174–83. 10.5392/JKCA.2013.13.03.174 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.OECD. Strengthening Social Cohesion in Korea. Paris: OECD Publishing, 2013. [Google Scholar]