Abstract

Introduction

Primary insomnia (PI) is commonly defined as a state of having disturbed daytime activities due to poor night-time sleep quality. Studies have demonstrated that it is a disorder of 24 h hyperarousal, expressed in terms of physiological, cognitive and cortical activation. Acupuncture is considered to be beneficial to restore the normal sleep–wake cycle. The aim of the trial is to assess the therapeutic effects of acupuncture on sleep quality and hyperarousal state in patients with PI.

Methods and analysis

This study is a randomised, patient-assessor-blinded, sham controlled trial. –88 eligible patients with PI will be randomised in a ratio of 1:1 to the intervention group (real acupuncture) and control group (sham acupuncture, superficial insertion at irrelevant acupuncture points). Acupuncture intervention will be given to all participants three times a week for 4 weeks, followed up for 8 weeks.

The primary outcome measures are the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) and Hyperarousal scale (HAS). The secondary outcomes are Fatigue scale-14 (FS-14), polysomnography (PSG), heart rate variability (HRV) and Morning Salivary Cortisol Level (MSCL). Outcomes will be evaluated at baseline, post-treatment period and 8 weeks follow-up. All main analyses will be carried out on the basis of the intention-to-treat principle.

Ethics/dissemination

This protocol has been approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of Beijing Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital (Beijing TCM Hospital) on 5 January 2015. The permission number is 2014BL-056-02. The study will present data concerning the clinical effects of treating primary insomnia with acupuncture. The results will help to demonstrate if acupuncture is an effective therapy for improving sleep quality in association with a decreased hyperarousal level as a possible underlying mechanism. The findings from this study will be shared with the healthcare professionals, general public and relevant organisations through publication of manuscripts and conference presentations.

Trial registration number

ISRCTN16079489; Pre-results.

Keywords: primary insomnia, Acupuncture, Sleep quality, Hyperarousal state, RCT

Background

As a common clinical condition, primary insomnia1 is defined as a symptom of prolonged sleep latency, difficulties in maintaining sleep, the experience of non-refreshing or poor sleep coupled with impairments of daytime functioning,2 including reduced alertness, fatigue, exhaustion, dysphoria and other symptoms. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders further defines the condition to be not attributable to a medical, psychiatric or environmental cause. Chronic insomnia (with symptoms at least 3 nights a week for at least 1 month) presents a substantially increased risk for other psychiatric disorders, especially depression,3 as well as for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.4 The prevalence of insomnia disorder is approximately 10–20%, with approximately 50% having a chronic course.5

Although primary insomnia is considered a sleep disorder, its pathophysiology suggests hyperarousal during sleep and wakefulness.6 Evidence of hyperarousal in insomniacs includes elevated whole-body metabolic rate during sleep and wakefulness, elevated cortisol and adrenocorticotropic hormone during the early sleep period, reduced parasympathetic tone in heart rate variability and increased high-frequency electroencephalographic activity during non-rapid eye movement sleep.7 Genetic, environmental, behavioural and physiological factors have been proposed to contribute to the aetiology and pathophysiology of hyperarousal-induced insomnia.5

For chronic insomnia, hypnotic medications (benzodiazepine receptor agonists in particular) and cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) have been first-line treatments. Although benzodiazepine receptor agonists are efficacious in the short-term management of insomnia, there is very limited evidence of their long-term treatment efficacy.8 Also, various adverse effects related to their use have been reported, including residual daytime sedation, cognitive impairment and medication dependence.9 CBTs, although clinically effective, are not widely used due to intense labour and lack of trained therapists.9 The guidance for clinicians in choosing the best treatment is limited so far, and the search for better treatment modality is ongoing.

As a major component of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), acupuncture has been used in the treatment of insomnia in China for thousands of years. The systematic reviews indicated that acupuncture could be effective against insomnia. New comprehensive and more strictly designed clinical studies, meanwhile, were encouraged to give more evidence.10–13

The previous trials of treatment of insomnia mostly focused on the effects of sleep quality; daytime functioning was not highly considered. Our pilot study suggested that verum acupuncture was more effective in increasing sleep quality and daytime functioning than sham acupuncture.14 Huang's systematic review indicated that acupuncture could modulate autonomic tone and central activation by its direct effects on peripheral nerves and muscles. Acupuncture may have great relevance for the modulation of sleep and wakefulness via a potential neural and/or hormonal mechanism.15

It has been suggested that patients with insomnia may benefit from treatment of their arousal level.16 However, the hyperarousal state was not evaluated in previous trials. On the basis of the results of our previous study and the consideration that acupuncture may reduce the level of hyperarousal, we designed this randomised controlled trial to investigate the efficacy of acupuncture on sleep quality and hyperarousal state for insomnia. A hyperarousal state will be assessed multidimensionally, including cognitive functions, autonomic nervous system activities and hypothalamic pituitary adrenocortical (HPA) axis functioning.

Heart rate variability (HRV) is a tool for autonomic nervous system (ANS) activity monitoring. It has been demonstrated that patients with insomnia showed modifications of heart rate and HRV parameters, consistent with increased sympathetic activity.17 Bonnet and Arand18 have found increased low-frequency power (LF) and decreased high-frequency power (HF) in insomniacs compared with contro1 across all sleep stages. Acupuncture has been shown to modify autonomic nervous system activities, as indicated by changes in HRV LF, HF as well as their ratio (LF/HF) in various studies.19–21 Therefore, we will use HRV as a tool to observe how acupuncture affects the ANS related to sleep cycles in this trial.

Insomnia has also been associated with a 24 h increase of adrenocorticotropic hormone and cortisol secretion, consistent with a disorder of central nervous system hyperarousal.22 Morning salivary cortisol level (MSCL) is correlated with sleep parameters.23 We will monitor its change via acupuncture as an indication of effects on HPA axis.

Methods

Objective

To demonstrate if acupuncture is an effective therapy for primary insomnia in association with a decreased hyperarousal level as a possible underlying mechanism.

Hypotheses

The verum acupuncture intervention, compared with the sham acupuncture intervention, will significantly improve sleep quality, as indicated by both subjective (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, PSQI) and objective (polysomnography, PSG) measurements after treatment.

Sleep improvements will be associated with changes of hyperarousal state, as measured by Hyperarousal scale (HAS), HRV and MSCL.

The verum acupuncture intervention, compared with the sham acupuncture intervention, will significantly reduce levels of fatigue during the daytime.

Trial design

This is a patient-assessor-blinded, single-centre, randomised and sham controlled trial which conforms to the CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials)24 and STRICTA (Standards for Reporting Interventions in Clinical Trials of Acupuncture) guidelines25 for acupuncture studies.

Participants and recruitment

Participants will be recruited from the outpatient clinic of Beijing TCM Hospital. Assuming a 20% dropout rate, a total of 88 eligible patients will be randomised in a ratio of 1:1 to the invention and control group and receive treatments for 4 weeks.

Inclusion criteria

Over 18 and under 65 years old

Primary insomnia by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV-TR) criteria

Reports of clinical symptoms of persistent insomnia (3 or more nights per week) for 3 months or longer

Score of 8 or above on the PSQI, 33 or above on the HAS

Not being treated with psychoactive medications

No problem with communication and intelligence

Signed the written informed consent form for the clinical trial

Exclusion criteria

Diagnoses of epilepsy, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, kidney failure, hypertension, metabolic diseases or benign prostatic hyperplasia

Diagnoses of depression, anxiety, schizophrenia or other severe mental disorders

Diagnoses of other sleep disorders, or discovery of any other sleep disorder on PSG at the baseline, such as obstructive sleep apnoea, rapid eye movement (REM) sleep disorder or restless legs syndrome

Pregnancy, breastfeeding or woman of childbearing age not on a proper method of birth control

Has had acupuncture for insomnia treatment in the past month

Alcohol and/or other drug abuse or dependence

Randomisation and allocation concealment

The central randomisation will be performed by the Research Center of Clinical Epidemiology, the Peking University Third Hospital. The random allocation sequence was generated with a block of 4. Randomisation numbers will be sealed in a predetermined computer-made randomisation opaque envelope. The patients’ screening sequence numbers will be printed outside the envelope, whereas the group names will be printed inside. All envelopes will be numbered consecutively and connected. Researchers who screen the eligible patients after baseline will separate the envelopes from the strain and open them according to the patients’ screening sequence numbers, and then assign the patients to either the treatment group or the control group.

Blinding

This is a patient-assessor-blinded trial, in which patients are not aware of their group assignments. The follow-up assessors will be blinded to the patients’ group assignments as well. Although acupuncturists will not be blinded to the group assignments, they will not be involved in the outcome assessments or data analyses.

To achieve blinding, both real and sham acupuncture groups will use the same kind of disposable, sterile steel needles (1.5-infiliform needle, 0.32 mm×40 mm); same number of needles per session (10–12 needles); same skin disinfection process with 75% alcohol; and retention for 30 min.

Intervention

Intervention group

Participants in the intervention group will receive acupuncture therapy three times a week for 4 weeks (shown in table 1). Du-20, DU-24, GB-13 and EX-HN1 will be punctured at a depth of 10 mm obliquely. SP-6 will be punctured 10 mm straightly, while PC6 and HT-7 will be inserted 5 mm perpendicularly. Needle manipulation will be applied to achieve ‘De Qi’. Needle retention will be 30 min.

Table 1.

Details of interventions

| Intervention group | Control group | |

|---|---|---|

| Points | Baihui (DU-20), Shenting (DU-24), Benshen (GB-13), Sishencong (EX-HN1), Neiguan (PC6), Sanyinjiao (SP6), Shenmen(HT7), all unilateral | Binao (LI-14), Shousanli (LI-10), Yangchi ((SJ4), Waiguan (SJ5), Fengshi (GB31), Futu (ST32) and Liangqiu (ST-34), all unilateral. |

| Depth description | Depth of needle insertion was at least 5–10 mm | Depth of needle insertion was at 2 mm |

| Needle retention time | 30 min | 30 min |

| Needle type | Stainless steel needles (0.32×40 mm, HuaTuo, China) | Stainless steel needles (0.32×40 mm, HuaTuo, China) |

| Frequency and duration of treatment sessions | Three times a week for 4 weeks | Three times a week for 4 weeks |

| Needle stimulation | De-qi sensation felt by practitioner and patient | Without De-qi sensation |

Control group

Participants in the control group will receive sham acupuncture therapy three times a week for 4 weeks. Sham acupuncture will be conducted by needling the acupoints of LI-14, LI-10, SJ4, SJ5, GB31, ST32 and ST-34. Stainless steel needles of the same specifications as the intervention group will be inserted superficially at a depth of 1 mm at the acupuncture points and kept for 30 min. According to the literature review, the acupoints in the control group have no therapeutic effect for insomnia. Meanwhile, manual stimulation and De qi will be avoided to minimise its placebo effect.

Outcome measures

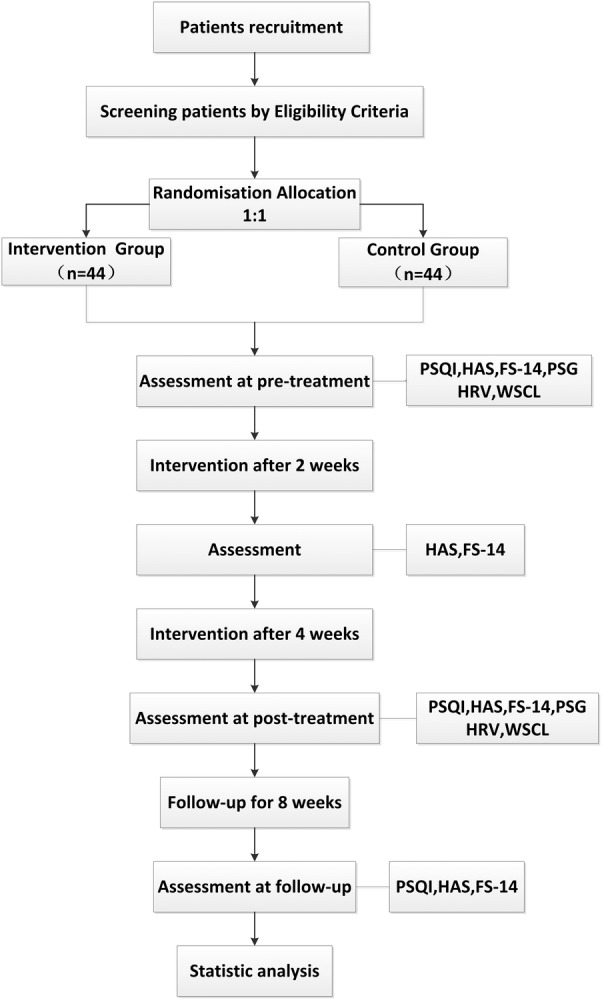

(All outcome measures are shown in table 2 and figure 1). PSQI, HAS, Sleep Diary, Fatigue scale (FS-14), PSG, HRV and MSCL will be the outcomes used to assess efficacy. Adverse events will be recorded to assess safety.

Table 2.

Time of visits and data collection

| Baseline | Treatment phase |

Follow-up phase 8th week | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| -1th Week | 0 Week | 2nd Week | 4th Week | ||

| Patients | |||||

| EEG | × | ||||

| HAMA,HAMD | × | ||||

| Sign the informed consent | × | ||||

| Medical history | × | ||||

| Randomisation | × | ||||

| Intervention | × | × | × | ||

| Sleep diary | × | × | × | ||

| Primary outcomes | |||||

| PSQI | × | × | × | ||

| HAS | × | × | × | × | |

| Secondary outcomes | |||||

| FS-14 | × | × | × | × | |

| PSG+HRV | × | × | |||

| MSCL | × | × | |||

| Adverse events | × | × | × | ||

FS-14, Fatigue scale-14; HAMA, Hamilton Anxiety scale; HAMD, Hamilton Depression scale; HAS, Hyperarousal scale; HRV, heart rate variability; MSCI, morning salivary cortisol level; PSG, polysomnography; PSQI, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study process. FS-14, Fatigue scale-14; HAMA, Hamilton Anxiety scale; HAMD, Hamilton Depression scale; HAS, Hyperarousal scale; HRV, heart rate variability; MSCI, morning salivary cortisol level; PSG, polysomnography; PSQI, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index.

Primary outcome

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

The PSQI is a self-rated questionnaire that assesses sleep quality and disturbance over a 1-month time interval.26 The items are divided into seven ‘component’ scores: sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleeping medication and daytime dysfunction. A lower global score reflects a better quality of sleep.27

Hyperarousal scale

The HAS is a 26-item self-report that measures information processing, tendencies to introspect, think about feelings, respond intensely to unexpected stimuli, and other behaviours that putatively involve cortical arousal.28 The higher the scores, the more heightened the state of arousal. A normal mean HAS score was reported to be 30.8.29 HAS can be used to assess the effect on cognitive and somatic hyperarousal.30

Secondary outcome

Sleep diary

One-week sleep diaries will be collected at baseline, 3 weeks after treatment and at the end of the follow-up. Patients will be asked to estimate the time taken to go to bed on the previous night, wake-up time, the time it took to fall asleep, the number of times they awoke after sleep onset, the feeling after getting up, total sleep time, factors that interfere with sleep, etc.

Fatigue scale-14

Fatigue is one of the main consequences of chronic insomnia reported by previous studies.31–33 FS-14 is a standardised questionnaire31 to reflect physical fatigue and mental figure. The higher the score, the worse the level of fatigue is.

Polysomnography

All patients will be evaluated for three nights (2 nights at 0 week and 1 night at 4th week) in a sleep laboratory with sound-attenuated, light-controlled and temperature-controlled rooms. During this evaluation, patients will be allowed to sleep ad libitum based on their habitual sleep time, with the recording time range from 22:00 to 7:00. This procedure included the following: EEG, bilateral electroculogram, submental electromyogram, oronasal airflow, thoracic and abdominal movements, arterial oxygen saturation (SaO2), snoring, ECG, leg movements and body position recordings. All PSG data will be collected and stored using an E-Series digital system (Compumedics, Abbotsford, Australia). All the computerised sleep data will be further edited by an experienced PSG technologist blinded to the group assignments. Sleep stages, respiratory events and periodic limb movements will be scored according to the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events V.2.0.34

Heart rate variability

The HRV study will be carried out on the EKG trace obtained in the PSG study during night-time and 24 h-long distance Holter monitor at baseline and post-treatment. Sampling rate will be 256 Hz, with a digital resolution of 16 bits per sample. Impedance will be kept below 5 KΩ. HRV will be evaluated at different sleep stages defined by PSG.

Morning salivary cortisol level

Patients will be required to provide one saliva specimen collection between 06:00–08:00 (30 min after awakening) at baseline and after treatment. The collection tubes will be kept in a −20°C freezer until being shipped to a laboratory (Zhongtonglanbo Clinical Examination Laboratories, Beijing) for analysis by chemiluminescence immunoassay. Patients will be told not to eat, drink, brush their teeth or engage in strenuous activity 1 h before saliva sampling.

Other outcome

Any adverse events (described as unfavourable or unintended signs, symptoms or diseases occurring after treatment) related to acupuncture treatment will be observed and reported by patients and practitioners during each patient visit. In addition, all vital signs and adverse events will be measured and recorded at each visit.

Setting

The trial will be conducted in Beijing TCM Hospital between 1 June 2015 and 31 January 2017.This protocol has been approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of the Beijing TCM Hospital on 5 January 2015.The permission number is 2014BL-056–02.

Figure 1 and table 2 describe the trial protocol. The eligibility of prospective participants will be determined by a researcher who is not involved in the assessment or treatment of the participants.

On the first arrival for screening meeting, patients will be given more detailed information about the procedures of the study. An ECG test will be performed to test the heart rate. All patients will be required to complete the Hamilton Anxiety scale (HAMA), Hamilton Depression scale (HAMD), HAS. Subjective sleep outcome will be collected as measured by PSQI. Patients without an abnormal heart rate and obvious depression and anxiety, with a score of 8 or above on the PSQI and a score of 33 or above on the HAS will be diagnosed as patients with clinical insomnia. Inclusion and exclusion criteria will be reassessed. One-week sleep diaries will be required to be collected prior to their second visit for the baseline evaluation in order to see whether they had experienced insomnia recently.

On the second visit, an expert will check the patients’ sleep diaries. If the patients really have experienced insomnia, they will be required to complete the test of PSG. The PSG is highly recommended as an objective tool for assessing insomnia. Patients without other sleep disorders such as obstructive sleep apnoea, REM sleep disorder and restless legs syndrome will be enrolled and registered into the clinical trial. They will be asked to provide written informed consent and complete the tests of FS-14, HRV and MSCL prior to first treatment.

Two weeks after the treatment, HAS will be measured again and changes in physical fatigue and mental fatigue will be observed using FS-14. Four weeks after the treatment, all patients will complete FS-14, HAS, PSQI, HRV, PSG and MSCL. 1-week sleep diaries will be collected 3 weeks after the treatment. At the end of the follow-up period, data of FS-14, HAS and the sleep diary for the 7th week will be collected for the last time. Results will be analysed by professionals blinded to the group allocation.

Statistical methods

Sample size

According to our previous pilot study, the global score of PSQI after 4 weeks’ treatment in the acupuncture group was 8.60±2.25, and that in the control group was 9.83±1.88.11 On the basis of 0.8 power to detect a significant difference (α=0.01, two-sided), 36 participants will be required for each group, which is calculated by PASS11. Allowing for a 20% withdrawal rate, we plan to enrol a total of 88 participants with 44 participants in each group.

Statistical analysis

De-identified outcome data will be analysed by a statistician blinded to group allocations using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) V.19.0 statistical software package. Significant levels will be set at p<0.05.

Data analysis of baseline characteristics and of primary and secondary outcomes will be based on the intention-to-treat principle. χ2 Test will be conducted for the case of proportions and independent sample t tests will be analysed for testing the baseline differences between the two groups. A repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) will be used to compare the effect of real and sham acupuncture. Missing data will be replaced according to the principle of the last observation carried forward.

Patient safety

Any adverse events (described as unfavourable or unintended signs, symptoms or diseases occurring after treatment) related to acupuncture treatment will be observed and reported by patients and practitioners during each patient visit. In addition, all vital signs and adverse events will be measured and recorded at each visit.

Quality control

All acupuncturists and assessors will be required to undergo special training prior to the trial to guarantee consistent practices. The training programme will include diagnoses, inclusion and exclusion criteria, location of the acupuncture points, acupuncture manipulation techniques and completion of case report forms. Dropouts and withdrawals from the study will be recorded through the intervention and follow-up periods. This trial will be monitored by the scientific research department of Beijing TCM Hospital. Periodic monitoring will guarantee accuracy and quality throughout the study.

Discussion

The aim of this trial is to investigate the efficacy of acupuncture on sleep quality and hyperarousal state for primary insomnia. Effectiveness indicators will be subjective and objective sleep duration and quality, ANS functioning by HRV measurements, and physiological changes in HPA axis state by morning cortisol level measurement. This trial will attempt to associate the effects of acupuncture on primary insomnia with its effects on hyperarousal state measured at multiple dimensions. We believe that this will be the first attempt in a clinical trial of primary insomnia investigating clinical effects as well as possible underlying mechanisms of acupuncture.

HRV will be used to assess changes in the ANS. Different sleep stages may have differences in autonomic tone when it occurs in the proximity of SWS or REM sleep.14 One of the strengths of this study is that we will measure HRV in each sleep stage separately. Using HRV and PSG together to evaluate HRV in different stages of wake and sleep, allowing a better description of the fluctuations of autonomic arousal of insomniacs in the course of the wake–sleep cycle.17

The use of an appropriate control group is critical in designing a high-quality clinical trial. Points selection is crucial for efficiency. The results of our previous trial have shown that the acupuncture points selected in the intervention group may improve both nocturnal sleep and daytime functioning. According to the literature review and clinical experiences, the acupoints in the sham group are mainly for local disease and have no therapeutic effect for insomnia.

In addition, the function of ‘De qi’ will be considered in the trial; it is based on subjective reporting of the patient (soreness, numbness, fullness, radiating sensation, etc) and is regarded as a sign of efficacy according to TCM. Most contemporary acupuncturists still seek De qi and believe it is fundamental to efficacy.35 The placebo effect produced by sham acupuncture was considered to have less influence on the disease, although needle pricking might induce non-specific physiological reactions.14

Our study will produce data on the treatment of primary insomnia with acupuncture. The results will help to demonstrate if acupuncture is an effective therapy for improving sleep quality or not, while observing its possible mechanistic associations. We will test the hypothesis that the effect of acupuncture on insomnia will be associated with inhibiting the hyperarousal state. The results of the trial might guide better selective use of acupuncture modality as a treatment for insomnia in the future.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere appreciation to Yi Yang, Guangxia Shi, Cun-zhi Liu for their helpful advice on the research design. They would like to express their gratitude to the acupuncture experts Hui-lin Liu for acupuncture operation.

Footnotes

Contributors: JG, WH and L-pW, contributed to the design of the study, drafting and editing of the manuscript. JG and C-yT wrote the first manuscript for this trial. WH edited the final manuscript. G-LW and FZ participated in the design of the trial and will conduct the acupuncture operation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: Beijing Scientific Committee (Z141107002514066) and Beijing Municipal Administration of Hospitals (ZYLX201412).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: This protocol has been approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of the Beijing TCM Hospital approved on 5 January 2015. The permission number is 2014BL-056-02.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. The international statistical classification of diseases and related health problems (ICD-10)[M]. World Health Organization, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fortier-Brochu E, Beaulieu-Bonneau S, Ivers H et al. Insomnia and daytime cognitive performance: a meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev 2012;16:83–94. 10.1016/j.smrv.2011.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baglioni C, Battagliese G, Feige B et al. Insomnia as a predictor of depression: a meta-analytic evaluation of longitudinal epidemiological studies. J Affect Disord 2011;135:10–19. 10.1016/j.jad.2011.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sofi F, Cesari F, Casini A et al. Insomnia and risk of cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2014;21:57–64. 10.1177/2047487312460020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buysse DJ. Insomnia. JAMA 2013;309:706–16. 10.1001/jama.2013.193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Riemann D, Spiegelhalder K, Feige B et al. The hyperarousal model of insomnia: a review of the concept and its evidence. Sleep Med Rev 2010;14:19–31. 10.1016/j.smrv.2009.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonnet MH, Arand DL. Hyperarousal and insomnia: state of the science. Sleep Med Rev 2010;14:9–15. 10.1016/j.smrv.2009.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Riemann D, Perlis ML. The treatments of chronic insomnia: a review of benzodiazepine receptor agonists and psychological and behavioral therapies. Sleep Med Rev 2009;13:205–14. 10.1016/j.smrv.2008.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Institutes of Health State. National Institutes of Health State of the Science Conference statement manifestations and management of chronic insomnia in adult, June 13–15, 2005. Sleep 2005;28:1049–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ernst E, Lee MS, Choi TY. Acupuncture for insomnia? An overview of systematic reviews. Eur J Gen Pract 2011;17:116–23. 10.3109/13814788.2011.568475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bezerra AG, Pires GN, Andersen ML et al. Acupuncture to treat sleep disorders in postmenopausal women: a systematic review. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2015;2015:563236 10.1155/2015/563236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao K. Acupuncture for the treatment of insomnia. Int Rev Neurobiol 2013;111:217–34. 10.1016/B978-0-12-411545-3.00011-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lan Y, Wu X, Tan HJ et al. Auricular acupuncture with seed or pellet attachments for primary insomnia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Complement Altern Med 2015;15:103 10.1186/s12906-015-0606-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guo J, Wang LP, Liu CZ et al. Efficacy of acupuncture for primary insomnia: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2013;2013:163850 10.1155/2013/163850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang W, Kutner N, Bliwise DL. Autonomic activation in insomnia: the case for acupuncture. J Clin Sleep Med 2011;7:95–102. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bonnet MH, Arand DL. Hyperarousal and insomnia. Sleep Med Rev 1997;1:97–108. 10.1016/S1087-0792(97)90012-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farina B, Dittoni S, Colicchio S. Heart rate and heart rate variability modification in chronic insomnia patients. Behav Sleep Med 2013;11:1–17. 10.1080/15402002.2013.741027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bonnet MH, Arand DL. Heart rate variability in insomniacs and matched normal sleepers. Psychosom Med 1998;60:610e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Litscher G, Cheng G, Cheng W et al. Sino-European transcontinental basic and clinical high-tech acupuncture studies—part 2: acute stimulation effects on heart rate and its variability in patients with insomnia. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2012;2012:916085 10.1155/2012/916085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chung JW, Yan VC, Zhang H. Effect of acupuncture on heart rate variability: a systematic review. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2014;2014:819871 10.1155/2014/819871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee S, Lee MS, Choi JY et al. Acupuncture and heart rate variability: a systematic review. Auton Neurosci 2010;155:5–13. 10.1016/j.autneu.2010.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vgontzas AN, Chrousos GP. Sleep, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, and cytokines: multiple interactions and disturbances in sleep disorders. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2002;31:15–36. 10.1016/S0889-8529(01)00005-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Backhaus J, Junghanns K, Hohagen F. Sleep disturbances are correlated with decreased morning awakening salivary cortisol. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2004;29:1184–91. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2004.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 2010;340:c332 10.1136/bmj.c332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.MacPherson H, Altman DG, Hammerschlag R et al. Revised Standards for Reporting Interventions in Clinical Trials of Acupuncture (STRICTA): extending the CONSORT statement. Acupunct Med 2010;28:83–93. 10.1136/aim.2009.001370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH et al. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res 1989;28:193–213. 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Backhaus J, Junghanns K, Broocks A et al. Test-retest reliability and validity of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index in primary insomnia. J Psychosom Res 2002;53:737–40. 10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00330-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hammad MA, Barsky AJ, Regestein QR. Correlation between somatic sensation inventory scores and hyperarousal scale scores. Psychosomatics 2001;42:29–34. 10.1176/appi.psy.42.1.29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pavlova M, Berg O, Gleason R et al. Self-reported hyperarousal traits among insomnia patients. Psychosom Res 2001;51:435–41. 10.1016/S0022-3999(01)00189-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Regestein Q, Pavlova M, Casares F. Validation of the hyperarousal scale in primary insomnia subjects. Sleep Res 1996;25:344. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chalder T, Berelowitz G, Pawlikowska T et al. Development of a fatigue scale. J Psychosom Res 1993;37:147–53. 10.1016/0022-3999(93)90081-P [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buysse DJ, Thompson W, Scott J et al. Daytime symptoms in primary insomnia: a prospective analysis using ecological momentary assessment. Sleep Med 2007;8:198–208. 10.1016/j.sleep.2006.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shekleton JA, Rogers NL, Rajaratnam SM. Searching for the daytime impairments of primary insomnia. Sleep Med Rev 2010;14:47–60. 10.1016/j.smrv.2009.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosenberg RS, Van Hout S. The American Academy of Sleep Medicine inter-scorer reliability program: sleep stage scoring. J Clin Sleep Med 2013;9:81–7. 10.5664/jcsm.2350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kong J, Gollub R, Huang T et al. Acupuncture De Qi, from qualitative history to quantitative measurement. J Altern Complement Med 2007;13:1059–70. 10.1089/acm.2007.0524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]