Abstract

Introduction

Residual pain is a major factor in patient dissatisfaction following total hip arthroplasty or total knee arthroplasty (THA/TKA). The proportion of patients with unfavourable long-term residual pain is high, ranging from 7% to 34%. There are studies indicating that a preoperative degree of central sensitisation (CS) is associated with poorer postoperative outcomes and residual pain. It is thus hypothesised that preoperative treatment of CS could enhance postoperative outcomes. Duloxetine has been shown to be effective for several chronic pain syndromes, including knee osteoarthritis (OA), in which CS is most likely one of the underlying pain mechanisms. This study aims to evaluate the postoperative effects of preoperative screening and targeted duloxetine treatment of CS on residual pain compared with care-as-usual.

Methods and analysis

This multicentre, pragmatic, prospective, open-label, randomised controlled trial includes patients with idiopathic hip/knee OA who are on a waiting list for primary THA/TKA. Patients at risk for CS will be randomly allocated to the preoperative duloxetine treatment programme group or the care-as-usual control group. The primary end point is the degree of postoperative pain 6 months after THA/TKA. Secondary end points at multiple time points up to 12 months postoperatively are: pain, neuropathic pain-like symptoms, (pain) sensitisation, pain catastrophising, joint-associated problems, physical activity, health-related quality of life, depressive and anxiety symptoms, and perceived improvement. Data will be analysed on an intention-to-treat basis.

Ethics and dissemination

The study is approved by the local Medical Ethics Committee (METc 2014/087) and will be conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (64th, 2013) and the Good Clinical Practice standard (GCP), and in compliance with the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (WMO).

Trial registration number

2013-004313-41; Pre-results.

Keywords: PAIN MANAGEMENT, REHABILITATION MEDICINE

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first randomised controlled trial to assess preoperative as well as early and late postoperative effects of a substantial preoperatively targeted duloxetine regimen.

By using a pragmatic trial design involving a care-as-usual control group, more insight will be gained into the effectiveness of duloxetine, with patient-centred end points focusing on everyday relevancy.

Owing to the pragmatic trial design, the direct effect of the duloxetine substance cannot be measured; instead, the effect of the total ‘targeted treatment package’ is measured.

Background and rationale

Total joint replacement (TJR) is considered to be a safe, successful and cost-effective procedure for the treatment of advanced osteoarthritis (OA).1–3 Despite its success, the overall incidence of dissatisfaction is high, as 7% of patients with total hip arthroplasty (THA) and 20% of patients with total knee arthroplasty (TKA) are dissatisfied 1 year after arthroplasty.4 5 The main factors associated with patient-perceived level of dissatisfaction after TJR are level of residual pain, functional outcome and accomplished level of preoperative expectations.4–7 Of all factors, residual pain seems to be the most prominent cause of dissatisfaction.4 5 7 8 The proportion of patients with unfavourable long-term residual pain is high, ranging from 7% to 23% after THA and 10% to 34% after TKA.9

Over the past decades, it has become clear that OA pain varies among patients with OA, from intermittent to constant pain and from nociceptive to neuropathic pain-(NP) like symptoms.10 These variations may be explained by OA-induced changes in the biochemical environment around peripheral joint nociceptors and joint structures.11 It is thought that these changes could lead to hyperexcitability of the peripheral (peripheral sensitisation) and ultimately the central nervous system (central sensitisation, CS).11–13 CS can be defined as an ‘increased responsiveness of nociceptive neurons in the central nervous system’, ‘this may include increased responsiveness due to dysfunction of endogenous pain control systems’.13a In a subset of patients, it is hypothesised that CS combined with peripheral articular nerve disruption is accountable for, or at least associated with, joint-related NP-like symptoms such as allodynia and hyperalgesia, and other characteristics such as spontaneous pain, widespread pain, referred pain and temporal summation.12–14

There are indications that preoperative signs/symptoms suggesting CS are associated with poorer postoperative outcomes and residual pain after TJR.15–17 Lundblad et al16 found less favourable pain relief 18 months after TKA in patients with preoperative features of possible CS such as low pain thresholds at remote sites (secondary hyperalgesia) and high preoperative visual analogue scale (VAS) scores for pain at rest (spontaneous pain). Wylde et al15 17 further showed that CS-associated features such as multiple-site pain and preoperative pain sensitisation at remote sites (secondary hyperalgesia) are independent determinants of residual pain 12 and 18 months after TKA. Hence, it is hypothesised that preoperative-targeted treatment of CS could be beneficial towards decreasing the level of residual postoperative pain.

There is preclinical18 19 and clinical evidence that duloxetine, a centrally acting antidepressant, is efficacious in the treatment of chronic pain conditions in which CS is most likely one of the prominent underlying pain mechanisms, such as diabetic peripheral NP,20 21 fibromyalgia22 and chronic low back pain.23 The mechanism of pain inhibition is thought to be related to the amelioration of serotonin and norepinephrine activity in the central nervous system.24 There is also preclinical25 and clinical evidence that duloxetine is beneficial for lowering chronic knee OA pain compared with a placebo.26–31 The observed knee OA pain relief was due to a direct analgesic effect and not due to mood improvement.

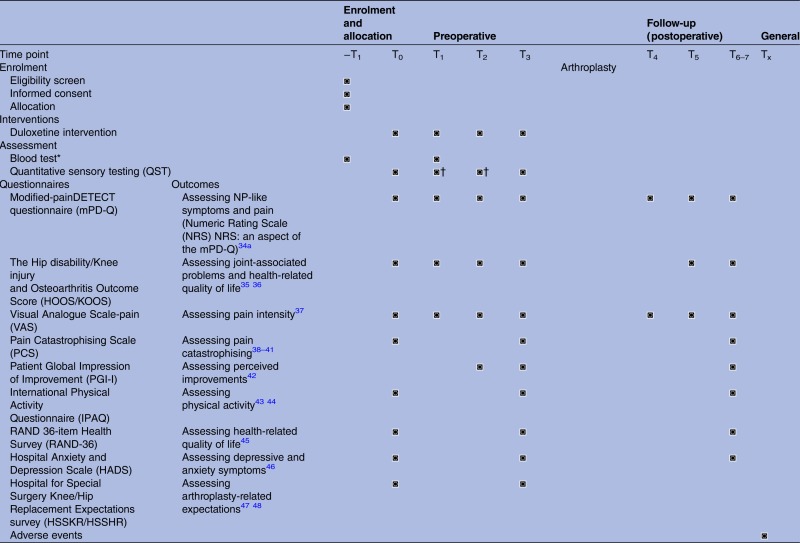

On the basis of the observed relationship between preoperative signs/symptoms indicating CS and negative postoperative outcomes, this study aims to evaluate the postoperative effects of preoperative-targeted duloxetine treatment of CS on residual pain after THA/TKA compared with care-as-usual. The primary objective is therefore to determine the effect of preoperative-targeted duloxetine treatment on residual pain 6 months after THA/TKA. The secondary objectives are to determine the effect at different preoperative and postoperative follow-up time points (table 1) on: pain, NP-like symptoms, (pain) sensitisation, pain catastrophising, joint-associated problems, physical activity, health-related quality of life, depressive and anxiety symptoms, perceived improvement and arthroplasty-related expectations.

Table 1.

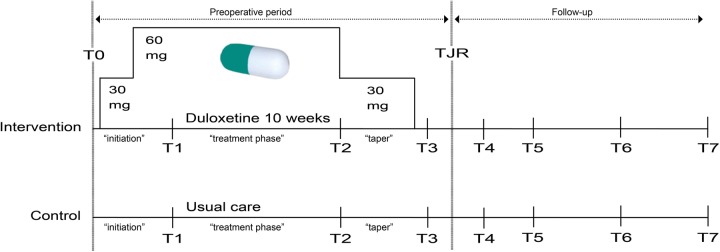

Schematic timeline

|

*Blood test at T1 is only applicable to the duloxetine intervention group.

†Only applicable to the duloxetine intervention group.

−T1, screening; T0, baseline; T1, days 14–17; T2, days 56–60; T3, 0–2 days preoperative; T4, days 2–3 postoperative; T5, weeks 5–7 postoperative; T6–7, 6 and 12 months postoperative ±2 weeks; Tx, no specific time point.

Methods and design

This study is a multicentre (University Medical Center Groningen (UMCG), Martini Hospital Groningen (MH) and Medical Center Leeuwarden (MCL)), pragmatic, open-label randomised controlled trial. After signing informed consent, eligible patients will be randomly allocated by means of a web-based system (ALEA, FormsVision, Abcoude, the Netherlands) to an intervention or a control group (figure 1). The intervention will consist of 10 weeks of preoperative duloxetine treatment (7 weeks on target dosage). This treatment period was chosen on the basis of two large placebo-controlled randomised control trials (RCTs) among patients with knee OA which showed that the main pain-relieving effect of duloxetine reached a plateau after 7 weeks on target dosage.27 28 To reduce the risk of developing side effects,32 the first week of treatment will be initiated with half of the target dose (30 mg/day). In the second week, there will be up-titration to the target dosage of 60 mg/day (2×30 mg/day capsule). The last two treatment weeks (weeks 9 and 10) are a drug-tapering phase: duloxetine dosage will be lowered to 30 mg/day to reduce the risk of developing discontinuation symptoms.33 In the control group, participants will receive no specific intervention and solely receive standard preoperative care-as-usual. However, in the perioperative and early postoperative period usage of agents to address specifically NP (like gabapentinoids) will be discouraged (by communicating this with the anaesthesiologist that is responsible for the participants’ pain management). Since, usage of these agents could potentially interfere with the study outcome(s). As the current waiting period for surgery is around 2–3 months, no significant treatment delay is expected. For each participant, the duration of the clinical trial will be around 15 months, including baseline visit, a ±11-week preoperative period and a 1-year postoperative follow-up period (table 1, figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic scheme: preoperative period, ±11-week including 10 weeks of duloxetine and a preoperative duloxetine-free period; follow-up period, postoperative up to 1 year; ‘initiation’, 2-week period, first week: 30 mg/day duloxetine, second week: 60 mg/day duloxetine; ‘treatment phase’, 6-week period, 60 mg/day duloxetine; ‘taper’, 2-week period, 30 mg/day duloxetine; TJR, total joint replacement (arthroplasty).

Patient selection and study population

When placed on the waiting list for THA/TKA, patients will be asked to fill in a questionnaire about NP-like symptoms (the modified-painDETECT questionnaire (mPD-Q)34 34a). The mPD-Q is derived from the original painDETECT questionnaire49 and is composed of seven items evaluating pain quality, one item evaluating pain pattern, and one item evaluating pain radiation. The score result is an aggregated score ranging from −1 to 38 points.49 Patients who are experiencing a possible or likely NP phenotype (mPD-Q score >12 points) and who are willing to consider participation will receive written information about the study. After about 2 weeks, the researchers will call the patients to ask if they have any questions regarding the study; if patients are willing to participate, they will be checked for inclusion and exclusion criteria (TB and WR).

Inclusion criteria

To be eligible to participate in this study, a patient must be an adult (age >18 years) diagnosed with primary hip/knee OA (based on clinical and radiological American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria) and having a possible or likely NP phenotype (mPD-Q score >12) at the time of screening. The latter criterion is included to identify patients who are most likely more at risk for developing residual pain, as research showed that characteristics of CS are more prevalent in patients with hip/knee OA with a possible or likely NP phenotype.50 51 On the basis of previous research, we anticipate that about 20–40% of the patients who will be screened experience a possible or likely NP phenotype.34 51–54

Exclusion criteria

Candidates who meet any of the following criteria will be excluded from participation:

General exclusion criteria:

Surgical hip or knee joint procedures performed in the past yeari;

Intra-articular knee/hip injection or knee/hip arthroscopy in the past 3 monthsi;

Cognitive and/or neurological disorders that could interfere strongly with questionnaire surveys (eg, dementia)ii;

An unstable and/or severely ill patient who is likely to be hospitalised during the course of the study or the illness compromises study participation significantlyii;

Planned or intended THA or TKA procedure within the study duration (current planned arthroplasty not included)iii;

A history of significant peripheral nerve injuryiv;

Previous exposure to duloxetinev.

Duloxetine-related exclusion criteria:

Allergy to the duloxetine capsule (or another serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors s (SNRI));

Usage of non-selective monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or SNRIs in the past year;

Usage of strong cytochrome P450 1A2 (CYP1A2) inhibitors;

History of peptic ulcer disease or bleeding disorder (or another substantial risk factor for bleeding, such as usage of coumarin derivatives);

Impaired liver function (alanine aminotransferase (ALAT) or aspartate aminotransferase (ASAT) >100 IU/L or elevated prothrombin time (international normalised ratio) >1.5), or known liver cirrhosis or liver transplantation;

Severe renal impairment (creatinine clearance–estimated glomerular filtration rate <30 mL/min), previous renal transplantation or under renal dialysis;

Psychiatric disorders, severe depression/major depressive disorder (based on Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) score >15 on the depression subscale)vi;

A history of alcohol or other substance abuse (excluding nicotine and caffeine) or dependence within the 5 years prior to enrolment;

History of cardiac arrhythmias, cardiac failure, myocardial infarction or irregular heartbeat at baseline (by checking radial pulse rhythm);

Hyponatraemia (<135 mmol/L) or a history of frequent hyponatraemias;

History of uncontrolled hypertension, blood pressure >180 mm Hg systolic or >110 mm Hg diastolic at baseline;

History of glaucoma (or increased intraocular pressure), uncontrolled thyroid disease or history of uncontrolled seizures;

Currently pregnant or lactating, or planning to become pregnant within the study period (self-assessed), unwillingness to comply with reproductive precautions; women who could become pregnant must be willing to comply with approved birth control measures.

Study procedures

Preoperative period

Baseline (T0)

Patients will visit the researcher of the outpatient clinic of their own hospital to screen for the following exclusion criteria: severe depression (based on HADS score >15 on the depression subscale), uncontrolled hypertension, hyponatraemia, impaired liver or renal function and pregnancy (applicable to women with childbearing potential; hCG-urine dipstick and, when screened positive, hCG will be obtained in serum). If all of the inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria are fulfilled, informed consent will be obtained and randomisation will follow. Randomisation in the web-based system will be executed by the local researcher (3 site-specific researchers). A stratification factor will be the type of arthroplasty (hip/knee). After randomisation, there is a baseline assessment, including patient characteristics and baseline values for outcome measures (see table 1). This is thus a pragmatic trial, so no restrictions will be imposed on usage of escape (pain) medication or other medication. However, in the perioperative and early postoperative period usage of agents to address specifically NP (like gabapentinoids) will be discouraged. Therefore local care-as-usual will be slightly modified for participants in the MH and MCL, since these two hospitals use gabapentinoids in the perioperative and early postoperative period (in a subset of patients).

Intervention group: ‘duloxetine’

Time point T0: medication period 1—‘initiation’

For safety reasons and to improve adherence, medication release takes place at three different time points. Since the risk of side effects is higher at the beginning of treatment, the first study period is relatively short (2 weeks). Prior to medication release, the participant will be informed and warned about possible side effects. The participant will also receive a chart to record usage and side effects. This chart will be collected at every subsequent preoperative visit.

Time point T1: medication period 2—‘treatment phase’

This time point follows after 2 weeks of usage. Participants will visit the outpatient clinic of their hospital and will receive a limited set of pain-related questionnaires (table 1), which they have to fill in prior to the visit. The visit will further consist of sensitisation measurements (quantitative sensory testing, QST) followed by duloxetine treatment evaluation. Drug accountability will be reported and any unused medication will be collected, registered and destructed following local protocol. Subsequently, duloxetine (60 mg/day) for the following 6 weeks will be handed over. Serum sodium level will be obtained once more to monitor for duloxetine-induced hyponatraemia, a complication that can occur early on after duloxetine initiation.56 57

Time point T2: medication period 3—‘taper phase’

This time point is defined as 8 weeks after duloxetine initiation and marks the beginning of the drug-tapering phase. This visit is identically structured as the previous mentioned time point T1. Medication (duloxetine 30 mg/day) for the final two treatment weeks will be handed over. Explicit warning will be given about discontinuation symptoms.

Time point T3: preoperative status

Participants will receive the full set of questionnaires by mail (see table 1), which they have to fill in the day before surgery. The questionnaires will be collected on the day of admission to the hospital. At the moment of collection, sensitisation measurements (QST) will be performed (see table 1). Since concomitant usage of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and SNRIs is associated with diminished platelet function and therefore with perioperative bleeding,58 surgery will be performed a minimal 4 days after last duloxetine usage (arthroplasty window, days 5–8).

Control group: ‘care-as-usual’

Time points T1, T2, T3

Time points T1 and T2 are defined as 2 weeks and 8 weeks after baseline (T0), respectively. Participants will receive a set of questionnaires at both time points (see table 1) by mail, which they have to fill in. After completion, they are asked to send them back by mail. Time point T3 is identical to time point T3 of the intervention group.

Follow-up

Follow-up procedures will be identical for both study groups (see figure 1). Time points T4 and T5, 2 days and 6 weeks postoperatively, consist of limited sets of pain-related questionnaires (see table 1). At T4, questionnaires will be collected at the ward, and at T5 at the outpatient clinic during the regular appointment with their orthopaedic surgeon. When collection at the hospital is not possible, the participant will receive the set of questionnaires by mail, to be filled in and sent back. Time points T6 and T7, 6 and 12 months postoperatively, will consist of the full set of questionnaires (see table 1), which participants will receive by mail and have to send back.

Criteria for withdrawal

Participants have the right to withdraw at any point during treatment without prejudice. The investigator or regulatory authority can discontinue a participant's participation in the trial at any time if medically or otherwise necessary. It is not advisable to discontinue duloxetine treatment abruptly, especially when taking 60 mg/day. A participant who wishes to discontinue must contact the investigator to obtain discontinuation advice.

Adverse events (AEs) and data safety monitoring

All AEs reported spontaneously by the participant or observed by the investigators or staff will be recorded. In case of a serious AE (SAE), the sponsor will report the SAE to the accredited medical ethics committee. Since every participant will undergo elective total hip or knee arthroplasty (THA/TKA), this potential SAE will not be seen as an SAE and this procedure and the related hospitalisation will not be reported as an SAE. However, prolonged hospitalisation (>14 days) will be reported as an SAE. Rehospitalisation (for any reason) will also be reported and handled as an SAE. Suspected unexpected serious adverse reactions (SUSARs) will be reported to the medical ethics committee and all AEs will be followed until they are gone, or until a stable situation has been achieved. The sponsor decided (approved by the medical ethics committee) that, on the basis of the standards set by national regulations (Nederlandse Federatie van Universitair Medische Centra (NFU) standards59), no Data and Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) will be installed, as the risk profile of duloxetine is well known and duloxetine is already registered as an analgesic agent in the USA by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use within patients with OA.55 However, if more than one SUSAR is observed, contact will be sought with the medical ethics committee to re-evaluate the study. No additional participants will be included during the re-evaluation period. The conduct and management will be monitored by an independent trained and educated monitor. On the basis of the negligible risk profile, minimal monitoring is required (according to the NFU standards59: one site visit per year).

Outcome measures

The following characteristics will be retrieved from patient questionnaires, physical examination, the hospital information system or medical records:

Patient characteristics

Gender, age, patient-reported height (cm) and weight (kg), family status, highest reached level of education, duration of OA pain symptoms, American Society of Anesthesiologists classification, Kellgren-Lawrence grade, previous joint procedures or injury, number of painful joint/body regions, comorbidities, smoking and alcohol consumption, and pain medication consumption.

Arthroplasty-related characteristics

Method of anaesthesia, type of arthroplasty, surgical approach, postoperative analgesic consumption and arthroplasty-related complications.

Safety parameters

(Severe) AEs, vital signs (blood pressure, pulse) and clinical laboratory testing.

Primary outcome

Primary outcome is the amount of residual pain 6 months after THA/TKA. The amount of (residual) pain will be measured with the pain subscale of the Hip disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (HOOS) or the Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS). These Dutch questionnaires are proven to be valid and reliable.35 36 The key postoperative time point 6 months was chosen as this is in practice considered as the first possible time point to evaluate the ‘success’ of the arthroplasty.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary objectives are to determine the effect at different preoperative and postoperative follow-up time points (see table 1) on pain, NP-like symptoms, pain catastrophising, joint-associated problems, physical activity, health-related quality of life, depressive and anxiety symptoms, perceived improvement and arthroplasty-related expectations. These outcomes will be assessed by means of several questionnaires at multiple follow-up time points (see table 1). In addition to questionnaires, QST will be performed at several preoperative time points to assess pain and sensitisation. Two QST modalities will be used: mechanical temporal summation (MTS) and blunt pressure pain thresholds (PPTs). Assessment will be performed at two locations, one close to the affected hip/knee and one at a location remote from the affected hip/knee (contralateral forearm).60 These two QST modalities will be executed by the local researcher. The researcher follows a standard operating procedure (SOP), based on the DFNS-QST protocol.61 Multiple OA studies made use of segments of this protocol (or nearly identical procedures).50 51 62 63

Mechanical temporal summation

MTS, a wind-up-like pain to repetitive non-invasive mechanical stimulation, is a clinical manifestation of central integration and is believed to be a sensitive measure of CS.63 64 The perceived intensity of a single pinprick stimulus (Optihair2 von frey filament 256mN, Marstock Nervtest, Germany) will be compared with that of a series of 10 repetitive stimuli at the same physical intensity (1/s applied within an area of 1 cm2). The entire procedure will be repeated three times. The wind-up ratio is calculated as the ratio: mean rating of the three series divided by the mean rating of the three single stimuli.

Blunt PPT

An algometer (Force Ten FDX 25 Digital force gage, Wagner, instruments, Greenwich, CT, USA; 1 cm2 flat rubber tip) will be used to quantify the pain threshold. PPTs are proven to be highly reliable at painful, non-painful and remote body sites.62 65 66 PPTs are considered to be a reflection of peripheral sensitisation/nociceptive processes at the site of the joint.60 At a remote site, it is considered to reflect systemic altered pain processing/CS.60 The PPTs at each site will be assessed three times and the average of those measurements will be noted.

Handling and storage of data and documents

Personal data will be handled confidentially. Every participant will receive a unique code; this code contains the number of the hospital (UMCG/MH/MCL) followed by a sequence number. Data of each participant will be collected under this unique code. A unique participant identification list will be used to link the data to the participant. The key to the code is safeguarded by the principal investigator. All source documents will be entered in an electronic case report form (OpenClinica). The retention period of the data and documents is 20 years.

Sample size

Sample-size calculation is performed with HOOS/KOOS pain as the primary outcome measure. On the basis of a previous OA study, the common SDs for the pain subscale scores of the HOOS and KOOS are 17.7 and 17.2, respectively.67 Since the smallest change score for the KOOS to be considered clinically relevant is 10 points (on a 0–100 scale),68 power calculation is based on this difference. To detect this difference with 80% power (two-sided significance level of 0.05), a total of 47 participants is needed per group. Taking into account the possibility of 20% protocol violators and/or dropouts, inclusion of 59 participants per group is aimed for (total group: 118 participants). It is anticipated that this sample could be obtained between October 2014 and the end of 2016.

Statistical considerations

All statistical analyses will be conducted by using the IBM SPSS (V.22). Descriptive statistics will be used to describe the demographic and baseline characteristics of the participants. Continuous variables will be summarised using means and SDs. Discrete variables will be summarised by proportions and percentages.

For the primary end point, a Student's t test (or a non-parametric equivalent in case of a skewed distribution) will be used to determine possible differences in pain on the KOOS/HOOS at 6 months postoperatively between the two groups. Generalised Estimating Equation (GEE) analysis will be used to determine possible differences in pain between the two groups over time, adjusted for relevant covariates. For the secondary end points, Student's t tests (or a non-parametric equivalent in case of a skewed distribution) will be used to determine possible differences in secondary outcome variables at multiple follow-up time points (see table 1) between the two groups. GEE analyses will be used to determine possible differences in secondary outcome variables between the two groups over time, adjusted for relevant covariates. All data analyses will be done on an intention-to-treat basis. A p value of <0.05 is considered statistically significant.

Dissemination

This study will be conducted according to the principles of the latest Declaration of Helsinki, the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (WMO) and the Good Clinical Practice standard (GCP). The study is investigator-initiated. No arrangements are made between the subsidising party and the investigator concerning publication of the research data. Independently of the outcome, the results of the study will be published in international peer-reviewed scientific journals. Patient data will be presented anonymously in any publication or scientific journal. All substantial amendments (modification to the protocol that is likely to affect the safety or the scientific value of the trial) will be notified to the local METc and to the competent authority Centrale Commissie Mensgebonden Onderzoek (CCMO).

Discussion

The Duloxetine in Osteoarthritis (DOA) study is, as far as we know, the first pragmatic randomised controlled clinical trial assessing the preoperative as well as the early and late postoperative effects of a substantial preoperative-targeted duloxetine regimen. To date, only one study has assessed the early and late postoperative effects of a single-dose or dual-dose perioperative duloxetine regimen in a TKA patient group.69 In this study, no significant differences on pain scores were observed up to 6 months postoperatively between two perioperative 60 mg doses of duloxetine and placebo. Our study differs significantly from this and other studies that focus on diminishing the risk of residual pain. First, in this study, only those patients will be included who are probably at a higher risk for developing residual pain, based on having a higher chance of experiencing preoperative CS. This entails a more tailored approach, as we think not all OA patients are centrally sensitised and could benefit from a targeted preoperative treatment package. Second, in general, previous studies on residual postoperative pain are based on the theory70 71 that surgery-induced tissue injury and acute postsurgical pain probably result in CS and residual pain, whereas our study is based on the theory that the preoperative CS status induced by long-lasting OA is key and, as a consequence, should be addressed preoperative instead of perioperative/postoperative. Furthermore, we believe that our chosen pragmatic trial design has validity to assess the effects of the treatment regimen, as it mimics real-life status with a care-as-usual control group as much as possible. Moreover, the end points of this pragmatic RCT are focused on the relevancy to everyday life, like hip-specific and knee-specific pain, function and quality of life. For these reasons, pragmatic randomised trials are an increasingly popular design to test implementation interventions.72 Conversely, owing to the design used, it will not be possible to analyse the direct effect of the duloxetine substance but rather the effect of the total targeted treatment package. Hence, this study is powered for the effect measured in the total group; only limited hip-specific/knee-specific conclusions can be drawn. However, no significant group differences are anticipated due to the shared underlying pain mechanism. Knowledge gained from this study can potentially improve postoperative pain relief and rehabilitation after TJR. Moreover, owing to an extensive preoperative treatment period, it could provide specific insight into the effectiveness of duloxetine in patients with advanced hip and knee OA with possible NP/CS.

Contributors: TB, WR, TMvR, SKB, IvdA-S and MS participated in the design of the study and research protocol. TB and WR will coordinate the study, are responsible for data acquisition, and will conduct statistical analysis. IvdA-S will provide statistical consultation. TB, WR, TMvR, AJtH, BD, WPZ, SKB, IvdA-S and MS were involved in the writing, editing and approval of the final manuscript.

Funding: This work is supported and financed by the Dutch Arthritis Foundation. (project number BP 12-3-401).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The local Medical Ethics Committee of UMCG has approved the trial (METc 2014/087), which is registered in the Dutch Trial registry (NTR 4744) and in the EudraCT database (2013-004313-41).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

This factor likely interferes significantly with the baseline measure.

This factor likely interferes significantly with participating adequately in a randomised controlled trail with multiple time points.

This factor significantly influences multiple postoperative outcome measures.

This factor will probably influence pain quality in the lower extremities.

This factor likely influences the patient's expectations of the duloxetine treatment.

Major depressive disorder is an exclusion criterion, since it is associated with an increased risk of suicide in the early stages of depression treatment by duloxetine.55

References

- 1.Ng C, Ballantyne J, Brenkel I. Quality of life and functional outcome after primary total hip replacement. A five-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2007;89:868–73. 10.1302/0301-620X.89B7.18482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Learmonth ID, Young C, Rorabeck C. The operation of the century: total hip replacement. Lancet 2007;370:1508–19. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60457-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Räsänen P, Paavolainen P, Sintonen H et al. Effectiveness of hip or knee replacement surgery in terms of quality-adjusted life years and costs. Acta Orthopaedica 2007;78:108–15. 10.1080/17453670610013501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scott C, Howie C, MacDonald D et al. Predicting dissatisfaction following total knee replacement: a prospective study of 1217 patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2010;92:1253–8. 10.1302/0301-620X.92B9.24394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anakwe RE, Jenkins PJ, Moran M. Predicting dissatisfaction after total hip arthroplasty: a study of 850 patients. J Arthroplasty 2011;26:209–13. 10.1016/j.arth.2010.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bourne RB, Chesworth BM, Davis AM et al. Patient satisfaction after total knee arthroplasty: who is satisfied and who is not? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2010;468:57–63. 10.1007/s11999-009-1119-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mannion AF, Kämpfen S, Munzinger U et al. The role of patient expectations in predicting outcome after total knee arthroplasty. Arthritis Res Ther 2009;11:R139 10.1186/ar2811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baker PN, van der Meulen JH, Lewsey J et al. , National Joint Registry for England and Wales. The role of pain and function in determining patient satisfaction after total knee replacement. Data from The National Joint Registry for England and Wales. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2007;89:893–900. 10.1302/0301-620X.89B7.19091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beswick AD, Wylde V, Gooberman-Hill R et al. What proportion of patients report long-term pain after total hip or knee replacement for osteoarthritis? A systematic review of prospective studies in unselected patients. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000435 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neogi T. The epidemiology and impact of pain in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil 2013;21:1145–53. 10.1016/j.joca.2013.03.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malfait AM, Schnitzer TJ. Towards a mechanism-based approach to pain management in osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2013;9:654–64. 10.1038/nrrheum.2013.138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dimitroulas T, Duarte RV, Behura A et al. Neuropathic pain in osteoarthritis: a review of pathophysiological mechanisms and implications for treatment. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2014;44:145–54. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2014.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thakur M, Dickenson AH, Baron R. Osteoarthritis pain: nociceptive or neuropathic? Nat Rev Rheumatol 2014;10:374–80. 10.1038/nrrheum.2014.47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13a. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2014.47. http://www.iasp-pain.org/Taxonomy#Centralsensitization (accessed 12 Dec 2015) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lluch E, Torres R, Nijs J et al. Evidence for central sensitization in patients with osteoarthritis pain: a systematic literature review. Eur J Pain 2014;18:1367–75. 10.1002/j.1532-2149.2014.499.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wylde V, Hewlett S, Learmonth ID et al. Persistent pain after joint replacement: prevalence, sensory qualities, and postoperative determinants. Pain 2011;152:566–72. 10.1016/j.pain.2010.11.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lundblad H, Kreicbergs A, Jansson K. Prediction of persistent pain after total knee replacement for osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2008;90:166–71. 10.1302/0301-620X.90B2.19640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wylde V, Palmer S, Learmonth I et al. The association between pre-operative pain sensitisation and chronic pain after knee replacement: an exploratory study. Osteoarthr Cartil 2013;21:1253–6. 10.1016/j.joca.2013.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iyengar S, Webster AA, Hemrick-Luecke SK et al. Efficacy of duloxetine, a potent and balanced serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor in persistent pain models in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2004;311:576–84. 10.1124/jpet.104.070656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mico JA, Berrocoso E, Vitton O et al. Effects of milnacipran, duloxetine and indomethacin, in polyarthritic rats using the Randall-Selitto model. Behav Pharmacol 2011;22:599–606. 10.1097/FBP.0b013e328345ca4e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raskin J, Pritchett YL, Wang F et al. A double blind, randomized multicenter trial comparing duloxetine with placebo in the management of diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain. Pain Med 2005;6:346–56. 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2005.00061.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wernicke JF, Pritchett YL, D'souza DN et al. A randomized controlled trial of duloxetine in diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain. Neurology 2006;67:1411–20. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000240225.04000.1a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arnold LM. Duloxetine and other antidepressants in the treatment of patients with fibromyalgia. Pain Med 2007;8(Suppl 2): S63–74. 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2006.00178.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Skljarevski V, Zhang S, Desaiah D et al. Duloxetine versus placebo in patients with chronic low back pain: a 12-week, fixed-dose, randomized, double-blind trial. J Pain 2010;11: 1282–90. 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Citrome L, Weiss-Citrome A. A systematic review of duloxetine for osteoarthritic pain: what is the number needed to treat, number needed to harm, and likelihood to be helped or harmed? Postgrad Med 2012;124:83–93. 10.3810/pgm.2012.01.2521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chandran P, Pai M, Blomme EA et al. Pharmacological modulation of movement-evoked pain in a rat model of osteoarthritis. Eur J Pharmacol 2009;613:39–45. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sullivan MD, Bentley S, Fan MY et al. A single-blind, placebo run-in study of duloxetine for activity-limiting osteoarthritis pain. J Pain 2009;10:208–13. 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chappell AS, Ossanna MJ, Liu-Seifert H et al. Duloxetine, a centrally acting analgesic, in the treatment of patients with osteoarthritis knee pain: a 13-week, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Pain 2009;146:253–60. 10.1016/j.pain.2009.06.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chappell AS, Desaiah D, Liu Seifert H et al. A double blind, randomized, placebo controlled study of the efficacy and safety of duloxetine for the treatment of chronic pain due to osteoarthritis of the knee. Pain Pract 2011;11:33–41. 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2010.00401.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hochberg MC, Wohlreich M, Gaynor P et al. Clinically relevant outcomes based on analysis of pooled data from 2 trials of duloxetine in patients with knee osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol 2012;39:352–8. 10.3899/jrheum.110307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frakes EP, Risser RC, Ball TD et al. Duloxetine added to oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for treatment of knee pain due to osteoarthritis: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Curr Med Res Opin 2011;27:2361–72. 10.1185/03007995.2011.633502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abou-Raya S, Abou-Raya A, Helmii M. Duloxetine for the management of pain in older adults with knee osteoarthritis: randomised placebo-controlled trial. Age Ageing 2012;41:646–52. 10.1093/ageing/afs072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dunner DL, Wohlreich MM, Mallinckrodt CH et al. Clinical consequences of initial duloxetine dosing strategies: comparison of 30 and 60 mg QD starting doses. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp 2005;66:522–40. 10.1016/j.curtheres.2005.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.http://www.fk.cvz.nl/Preparaatteksten/D/duloxetine.asp (accessed 2 Dec 2013).

- 34.Hochman JR, Gagliese L, Davis AM et al. Neuropathic pain symptoms in a community knee OA cohort. Osteoarthr Cartil 2011;19:647–54. 10.1016/j.joca.2011.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34a.Rienstra W, Blikman T, Mensink FB et al. The Modified painDETECT Questionnaire for Patients with Hip or Knee Osteoarthritis: Translation into Dutch, Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Reliability Assessment. PloS one 2015;10:e0146117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Groot IB, Favejee MM, Reijman M et al. The Dutch version of the Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score: a validation study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2008;6:16 10.1186/1477-7525-6-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.De Groot IB, Reijman M, Terwee CB et al. Validation of the Dutch version of the Hip disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score. Osteoarthr Cartil 2007;15:104–9. 10.1016/j.joca.2006.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Price DD, McGrath PA, Rafii A et al. The validation of visual analogue scales as ratio scale measures for chronic and experimental pain. Pain 1983;17:45–56. 10.1016/0304-3959(83)90126-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sullivan MJ, Bishop SR, Pivik J. The pain catastrophizing scale: development and validation. Psychol Assess 1995;7:524 10.1037/1040-3590.7.4.524 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lame IE, Peters ML, Kessels AG et al. Test-retest stability of the Pain Catastrophizing Scale and the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia in chronic pain over a longer period of time. J Health Psychol 2008;13:820–6. 10.1177/1359105308093866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Crombez G, Eccleston C, Baeyens F et al. When somatic information threatens, catastrophic thinking enhances attentional interference. Pain 1998;75:187–98. 10.1016/S0304-3959(97)00219-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Crombez G, Vlaeyen JW, Heuts PH et al. Pain-related fear is more disabling than pain itself: evidence on the role of pain-related fear in chronic back pain disability. Pain 1999;80:329–39. 10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00229-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guy W. ECDEU assessment manual for psychopharmacology. US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Public Health Service, Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration, National Institute of Mental Health, Psychopharmacology Research Branch, Division of Extramural Research Programs, 1976:217–22. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Booth ML, Ainsworth BE, Pratt M et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2003;195:3581–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Blikman T, Stevens M, Bulstra SK et al. Reliability and validity of the Dutch version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire in patients after total hip arthroplasty or total knee arthroplasty. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2013;43:650–9. 10.2519/jospt.2013.4422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vander Zee KI, Sanderman R, Heyink JW et al. Psychometric qualities of the RAND 36-Item Health Survey 1.0: a multidimensional measure of general health status. Int J Behav Med 1996;3:104–22. 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0302_2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spinhoven P, Ormel J, Sloekers P et al. A validation study of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in different groups of Dutch participants. Psychol Med 1997;27:363–70. 10.1017/S0033291796004382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van den Akker-Scheek I, van Raay JJ, Reininga IH et al. Reliability and concurrent validity of the Dutch hip and knee replacement expectations surveys. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2010;11:242 10.1186/1471-2474-11-242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mancuso CA, Graziano S, Briskie LM et al. Randomized trials to modify patients’ preoperative expectations of hip and knee arthroplasties. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2008;466:424–31. 10.1007/s11999-007-0052-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Freynhagen R, Baron R, Gockel U et al. Pain DETECT: a new screening questionnaire to identify neuropathic components in patients with back pain. Curr Med Res Opin 2006;22: 1911–20. 10.1185/030079906X132488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gwilym SE, Keltner JR, Warnaby CE et al. Psychophysical and functional imaging evidence supporting the presence of central sensitization in a cohort of osteoarthritis patients. Arthritis Rheum 2009;61:1226–34. 10.1002/art.24837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hochman J, Davis A, Elkayam J et al. Neuropathic pain symptoms on the modified painDETECT correlate with signs of central sensitization in knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil 2013;21:1236–42. 10.1016/j.joca.2013.06.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shigemura T, Ohtori S, Kishida S et al. Neuropathic pain in patients with osteoarthritis of hip joint. Eur Orthop Traumatol 2011;2:73–7. 10.1007/s12570-011-0070-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ohtori S, Orita S, Yamashita M et al. Existence of a neuropathic pain component in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. Yonsei Med J 2012;53:801–5. 10.3349/ymj.2012.53.4.801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Valdes AM, Suokas AK, Doherty SA et al. History of knee surgery is associated with higher prevalence of neuropathic pain-like symptoms in patients with severe osteoarthritis of the knee. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2014;43:588–92. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2013.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cymbalta (duloxetine hydrochloride) FULL PRESCRIBING INFORMATION. http://pi.lilly.com/us/cymbalta-pi.pdf (accessed 18 Nov 2013).

- 56.Giorlando F, Teister J, Dodd S et al. Hyponatraemia: an audit of aged psychiatry patients taking SSRIs and SNRIs. Curr Drug Saf 2013;8:175–80. 10.2174/15748863113089990036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jacob S, Spinler SA. Hyponatremia associated with selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors in older adults. Ann Pharmacother 2006;40:1618–22. 10.1345/aph.1G293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.de Abajo FJ. Effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors on platelet function. Drugs Aging 2011;28:345–67. 10.2165/11589340-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kwaliteitsborging mensgebonden onderzoek 2.0, Nederlandse Federatie van Universitair Medische Centra. http://www.nfu.nl/img/pdf/NFU12.6053_Kwaliteitsborging_mensgebonden_onderzoek_2.0.pdf (accessed 18 Jul 2015).

- 60.Suokas AK, Walsh DA, McWilliams DF et al. Quantitative sensory testing in painful osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoarthr Cartil 2012;20:1075–85. 10.1016/j.joca.2012.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rolke R, Baron R, Maier C et al. Quantitative sensory testing in the German Research Network on Neuropathic Pain (DFNS): standardized protocol and reference values. Pain 2006;123:231–43. 10.1016/j.pain.2006.01.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Arendt-Nielsen L, Nie H, Laursen MB et al. Sensitization in patients with painful knee osteoarthritis. Pain 2010;149:573–81. 10.1016/j.pain.2010.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Neogi T, Frey-Law L, Scholz J et al. Sensitivity and sensitisation in relation to pain severity in knee osteoarthritis: trait or state? Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:682–8. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nie H, Arendt-Nielsen L, Madeleine P et al. Enhanced temporal summation of pressure pain in the trapezius muscle after delayed onset muscle soreness. Exp Brain Res 2006;170:182–90. 10.1007/s00221-005-0196-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wessel J. The reliability and validity of pain threshold measurements in osteoarthritis of the knee. Scand J Rheumatol 1995;24:238–42. 10.3109/03009749509100881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Walton DM, Levesque L, Payne M et al. Clinical pressure pain threshold testing in neck pain: comparing protocols, responsiveness, and association with psychological variables. Phys Ther 2014;94:827–37. 10.2522/ptj.20130369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Duivenvoorden T, Vissers M, Verhaar J et al. Anxiety and depressive symptoms before and after total hip and knee arthroplasty: a prospective multicentre study. Osteoarthr Cartil 2013;21:1834–40. 10.1016/j.joca.2013.08.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Roos EM, Lohmander LS. The Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS): from joint injury to osteoarthritis. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2003;1:64 10.1186/1477-7525-1-64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ho KY, Tay W, Yeo MC et al. Duloxetine reduces morphine requirements after knee replacement surgery. Br J Anaesth 2010;105:371–6. 10.1093/bja/aeq158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Woolf CJ, Chong M. Preemptive analgesia-treating postoperative pain by preventing the establishment of central sensitization. Anesth Analg 1993;77:362–79. 10.1213/00000539-199377020-00026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wilder-Smith OH, Arendt-Nielsen L. Postoperative hyperalgesia: its clinical importance and relevance. Anesthesiology 2006;104:601–7. 10.1097/00000542-200603000-00028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Allen K, Bierma-Zeinstra S, Foster NE et al. OARSI Clinical Trials Recommendations: design and conduct of implementation trials of interventions for osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil 2015;23:826–38. 10.1016/j.joca.2015.02.772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]