Abstract

Objectives

Our aim was to explore readiness to engage in exercise among people living with HIV and multimorbidity.

Design

We conducted a descriptive qualitative study using face-to-face semistructured interviews with adults living with HIV.

Setting

We recruited adults (18 years or older) who self-identified as living with HIV and 2 or more additional health-related conditions from a specialty hospital in Toronto, Canada.

Participants

14 participants with a median age of 50 years and median number of 9 concurrent health-related conditions participated in the study. The majority of participants were men (64%) with an undetectable viral load (71%).

Outcome measures

We asked participants to describe their readiness to engage in exercise and explored how contextual factors influenced their readiness. We analysed interview transcripts using thematic analysis.

Results

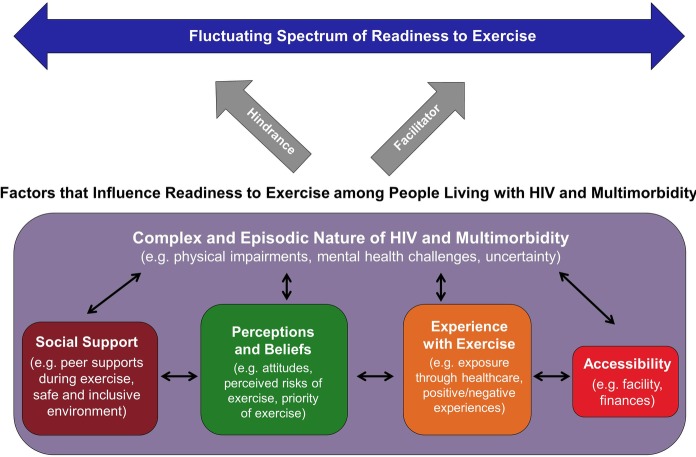

We developed a framework to describe readiness to engage in exercise and the interplay of factors and their influence on readiness among adults with HIV and multimorbidity. Readiness was described as a diverse, dynamic and fluctuating spectrum ranging from not thinking about exercise to routinely engaging in daily exercise. Readiness was influenced by the complex and episodic nature of HIV and multimorbidity comprised of physical impairments, mental health challenges and uncertainty from HIV and concurrent health conditions. This key factor created a context within which 4 additional subfactors (social supports, perceptions and beliefs, past experience with exercise, and accessibility) may further hinder or facilitate an individual's position along the spectrum of readiness to exercise.

Conclusions

Readiness to engage in exercise among people living with HIV is a dynamic and fluctuating construct that may be influenced by the episodic nature of HIV and multimorbidity and 4 subfactors. Strategies to facilitate readiness to exercise should consider the interplay of these factors in order to enhance physical activity and subsequently improve health outcomes of people with HIV and multimorbidity.

Keywords: QUALITATIVE RESEARCH, REHABILITATION MEDICINE, exercise, multi-morbidity, episodic disability

Strengths and limitations of this study.

To our knowledge, this is the first qualitative study to explore readiness to engage in exercise among people living with HIV and multimorbidity.

Using a qualitative approach with one-on-one semistructured interviews provided valuable insight into the perspectives, attitudes and conditions that influence readiness to engage in exercise among people living with HIV.

Healthcare providers may use this Framework to consider the interplay of factors that may enhance or hinder physical activity among people living with HIV and multimorbidity.

This study was conducted at a specialty HIV hospital in an urban setting in Canada; hence, it is unclear how the results may transfer to the experiences of people living with HIV and multimorbidity in low-income or rural settings.

Additional factors, beyond those outlined in this study, may impact readiness to engage in exercise among people living with HIV and multimorbidity and further research should endeavour to explain the relationships between factors.

Introduction

As people living with HIV (PLWH) are living longer, they are susceptible to developing health conditions arising from HIV, long-term use of highly active antiretroviral therapy and ageing.1 2 As a result, multimorbidity, defined as the simultaneous occurrence of two or more medical conditions, is becoming increasingly common among PLWH.3–7 The combination of HIV, ageing and associated multimorbidity can create a myriad of physical, cognitive, mental and social health-related challenges for PLWH.8–11 Collectively these health-related challenges may be conceptualised as disability.10–13 The Episodic Disability Framework describes the unique dimensions of disability experienced by PLWH, including fluctuating physical impairments and uncertainty.12 13 Disability may be exacerbated or alleviated by intrinsic (living strategies, personal attributes) and extrinsic (social support, stigma) contextual factors and may impact overall health for PLWH.13 Hence, the Episodic Disability Framework serves as a valuable resource and lens to understand the health-related challenges among people living longer with HIV and added multimorbidity, particularly as they relate to engagement in health-promoting behaviours.

Self-management strategies, such as physical activity and exercise, can address disability and optimise health outcomes for PLWH.14 15 Engaging in aerobic and progressive resistance exercise is safe and can improve overall fitness in PLWH who are medically stable.16–19 Despite these benefits, a large proportion of PLWH are not engaging in physical activity or exercise on a regular basis; however, the reason for this disparity is unclear.20

When exploring exercise as a self-management approach for PLWH, it is important to consider the concept of readiness as it relates to health behaviour change. Readiness can be understood as an individual's predisposition to engage in a health behaviour change or the indication of a central motivating force.21 The transtheoretical model (TTM) suggests that health behaviour change occurs with individuals moving through five stages of readiness: precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action and maintenance.22–24 Basta et al22 investigated the distribution of the TTM stages of change in exercise behaviour among PLWH and found approximately 40% of the sample were in the precontemplation, contemplation or preparation stages. While this approach provided meaningful insight into the applicability of the TTM, it did not capture the factors that impact engagement, or reasons why PLWH are or are not engaging in exercise.22 Our aim was to explore readiness to engage in exercise among PLWH and multimorbidity.

Methods

We conducted a descriptive qualitative study employing face-to-face semistructured interviews.25 26 We recruited adults 18 years of age or older, living with HIV who self-identified as having at least two additional health-related challenges from a specialty hospital in Toronto, Canada,27 using flyers that were posted on site as well as distributed in person on site. Members of the team identified themselves to potential participants as students in the Department of Physical Therapy at the University of Toronto (AS, KV, DE, DK, PL) who were advised by a team of faculty and community advisors throughout the research (KKO, SCC, PJ).

Data collection

We developed an interview guide to explore the perspectives and attitudes of PLWH and multimorbidity regarding their readiness to engage in exercise (see online supplementary additional file 1). Interviews were conducted at the specialty hospital in pairs by five members of the team (AS, KV, DE, DK, PL); one interviewer and the other took field notes. Each interview was audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Transcripts were checked for accuracy by the interviewer.

bmjopen-2015-010029supp1.pdf (357.6KB, pdf)

We also administered a self-reported demographic questionnaire asking participants about their age, gender, year of diagnosis, concurrent health conditions, and their perceived readiness to engage in exercise (see online supplementary additional file 2).28 29 Using the TTM, we devised an item on the demographic questionnaire asking participants to identify which statement best described their level of exercise activity: (1) I currently do not exercise and I do not intend to start exercise in the next 6 months; (2) I currently do not exercise, but I am thinking about starting to exercise in the next 6 months; (3) I currently exercise some, but not regularly; (4) I currently exercise regularly, but I have only begun doing so within the past 6 months; (5) I currently exercise regularly, and have done so for longer than 6 months; and (6) I have exercised regularly in the past, but I am not doing so currently.29 See online supplementary additional file 2 for the demographic questionnaire that includes the concurrent health condition and TTM item.

bmjopen-2015-010029supp2.pdf (265.7KB, pdf)

Data analysis

We analysed interview transcripts using thematic analysis.30 Each transcript was independently coded by a pair of researchers, and then jointly reviewed to ensure comprehensibility of the coding process. We used the detailed coding of the first three transcripts to inform the development of a coding scheme used to analyse remaining transcripts. The coding scheme continued to develop as new codes emerged from the analysis of subsequent interviews. All data and codes were imported into NVivo V.10 qualitative software for data management (QSR International. NVivo qualitative data analysis software. V.10; 2012).

We developed coding summaries and then grouped similar codes into broader themes and organised themes as they related to readiness to exercise. All transcripts were coded in pairs by five members of the team (AS, KV, DE, DK, PL); a smaller subset of transcripts were coded and discussed by all members of the team. We employed an audit trail, reflexive dialogue and multiple group discussions of the analyses of codes and themes to enhance analytical rigor.31

Results

Fourteen participants took part in a one-on-one semistructured interview (each approximately 60 min in length) between January and May 2015. The majority of participants were men (64%), with an undetectable viral load (71%), and median age of 50 years (table 1). Participants were living with a median of nine self-reported concurrent health conditions in addition to HIV. Participants ranged from 57% in the contemplation and preparation stages to 28% in the action and maintenance stages on the TTM.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants (n=14)

| Characteristic | Number of participants |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Man | 9 |

| Woman | 5 |

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 50 (46, 53) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Caucasian | 5 |

| Aboriginal/first nation | 2 |

| Other | 3 |

| Not identified | 4 |

| Highest education level achieved | |

| Master's degree | 1 |

| College degree | 2 |

| Some college credits completed | 7 |

| Bachelor's degree | 2 |

| Less than high school | 1 |

| Not reported | 1 |

| Year of HIV diagnosis, median (IQR) | 1991 (1988, 1998) |

| Currently taking antiretroviral therapy | 14 |

| Viral load | |

| Undetectable | 10 |

| Detectable | 2 |

| Unknown | 2 |

| Self-reported concurrent health conditions (in addition to HIV). Number of participants living with… | |

| 2–5 conditions | 3 |

| 6–10 conditions | 5 |

| 11–15 conditions | 3 |

| 16 or more conditions | 3 |

| Median number of concurrent health conditions (IQR) | 9 (6, 12) |

| Most commonly self-reported concurrent health conditions. Number of participants living with… | |

| Addiction | 7 |

| Asthma | 5 |

| Cancer | 5 |

| Eye disorder | 5 |

| Hepatitis C | 5 |

| Mental health conditions (eg, anxiety, depression) | 4 |

| Muscle pain | 4 |

| Joint pain | 4 |

| Hypertension | 3 |

| Peripheral neuropathy | 2 |

| Arrhythmia | 2 |

| Frailty | 2 |

| Hepatitis B | 2 |

| Neurocognitive decline | 2 |

| Self-reported stage of change for exercise (TTM) | |

| Precontemplation | 0 |

| Contemplation | 2 |

| Preparation | 6 |

| Action | 1 |

| Maintenance | 3 |

| Relapse | 1 |

| Unknown | 1 |

TTM, transtheoretical model; IQR, interquartile range.

Framework of readiness to exercise in PLWH and multimorbidity

We developed a Framework to describe readiness to engage in exercise and the factors that influence participation among PLWH and multimorbidity (figure 1). In this Framework, readiness is described as a dynamic spectrum ranging from not thinking about exercise, to routinely engaging in daily exercise. Readiness can fluctuate based on many factors, including one key factor and four subfactors. The influence of each factor is not strictly positive or negative. Rather, each has the capacity to hinder or facilitate readiness to engage in exercise at any given time.

Figure 1.

Framework of readiness to engage in exercise among people living with HIV and multimorbidity. Readiness is a fluctuating and dynamic spectrum that is influenced (hindered or facilitated) by the complex and episodic nature of HIV and multimorbidity (physical impairments, mental health challenges, and uncertainty) and four subfactors (social support, perceptions and beliefs, experience with exercise, accessibility).

The complex and episodic nature of living with HIV and multimorbidity emerged as an overarching factor that influenced participants’ readiness. This key factor encompassed physical impairments, mental health challenges and uncertainty that resulted from the health-related consequences (or disability) from HIV and concurrent health conditions experienced by PLWH. The complex and episodic nature of HIV and multimorbidity created a context within which four additional subfactors (social supports, perceptions and beliefs, past experience with exercise, and accessibility) may influence an individual's position along the fluctuating spectrum of readiness. Bidirectional arrows between the subfactors indicate that these circumstances do not occur in isolation; rather each has the capacity to influence the other subfactors and influence readiness to engage in exercise.

Readiness to exercise in PLWH and multimorbidity

Participants expressed a diverse range of perspectives regarding their position on the readiness to exercise spectrum (figure 1). Some participants indicated they were not ready to exercise, and often expressed a lack of motivation or interest in exercise:

There's a part of me that's [like] ‘what's the point’. (INT-11)

Several participants described themselves as ready to engage, but were aware of the limitations they faced due to HIV and multimorbidity:

As of right now with my current abilities I feel I am ready to exercise in limited ways that respect what my body can and cannot do. (INT-1)

Other participants described themselves as more ready, including one participant who was actively engaged in exercise:

I'm kind of at the point now where I basically have to go to the gym. I don't even think about it, it's just like routine, it's religious now. (INT-3)

The opinions articulated through the interviews supported the view of readiness to engage in exercise as a dynamic construct that fluctuated over time:

There has to be a proper balance and you have to learn what your body can take and what it can't. And that changes over time as well. I myself was a very active person and at the moment I'm not. But I will be again. (INT-1)

The majority of participants felt ready to engage in exercise amidst the unique circumstances they faced, particularly related to the complexity of living with HIV and multimorbidity:

Readiness [to exercise] for me is like when you're ready, despite all the other health conditions, substance use issues, life factors, housing situation. […] People are complicated. (INT-8)

When describing readiness to engage in exercise, participants described why they were or were not exercising, and the specific factors that made them more or less ready to engage.

Key factor: complex and episodic nature of HIV and multimorbidity

Participants expressed how living with the episodic nature of HIV and multimorbidity created complexity—understood as the day-to-day challenges associated with managing multiple health conditions. Here we describe physical impairments, mental health challenges and uncertainty as separate, but inter-related concepts that relate to the disability experience and influence readiness to engage in exercise.

Physical impairments

Participants discussed how living with physical impairments factored into their perceived ability, willingness and motivation to exercise. The disability experience was complicated by day-to-day variations of pain, fatigue and side effects of treatment. For some participants, these circumstances created obstacles barring their readiness to exercise:

My body is aching and sore, my lungs are sore, it’s hard to catch a good breath, so it’d be hard to exercise because of that. (INT-7)

[Exercise] should be a number one priority, but […] it’s not. Because you’re living with so much. (INT-1).

In contrast, others described exercise as a beneficial self-management approach when living with HIV and other chronic conditions:

I feel [exercise is] even more important now, ‘cause I think [it can] be a real positive to longevity and one's overall health […] I feel it was important before [but] it’s even more now [since being diagnosed with HIV], just like eating well. (INT-9)

Mental health challenges

The variable impact of multimorbidity on readiness was demonstrated by participants’ descriptions of living with mental health conditions, such as depression. For one participant, living with depression hindered readiness to engage consistently in exercise:

I usually start [exercising] but I end up losing interest real quick […] I lose interest in things quite easily. It’s part of the depression. (INT-7)

Alternatively, another participant expressed how living with depression helped him identify the utility of exercise as a management strategy, which positively impacted his readiness:

I can tell the difference when I don’t go [exercise] and when I do go. My moods are so different, it’s like day and night […] when my moods are really positive, my whole body is in a different state. (INT-3)

Further, other participants saw exercise as a way to overcome depression and improve their overall well-being:

The long term survivor needs to be exercising because we’ve been here so long and been through so much […]exercise actually helps stimulate the body and the brain hormones to help lift out of depression and keep a positive attitude. It makes it easier to help maintain and set goals and […] see the actual physical return. (INT-1)

Uncertainty

Participants expressed how living with an episodic illness, involving fluctuating levels of well-being and health crises, influenced their readiness to engage in exercise. For some, these fluctuations in health created an element of uncertainty that made it difficult to institute new health-promoting behaviours and resulted in barriers to readiness to exercise:

[Exercise is] very tiring and you have to be dedicated [with] a strict routine. At this time, […] it’s not possible [to have a] strict routine because every day is a different day when you’re sick or not sick. […] You're too sick to [exercise] and then you get into a rut where you're used to not doing it. (INT-5)

Some explained that although the episodic nature of HIV and multimorbidity limited their ability to exercise from time to time, the impact was temporary and did not significantly affect their position on the readiness spectrum:

[I'm not currently exercising] only because […] I’m going though these [chemotherapy] treatments, cause if I wasn't going though these treatments, I’d be going [to the gym] everyday. (INT-3)

Subfactors that influence readiness to exercise

Four subfactors additionally influenced readiness to exercise among PLWH and multimorbidity.

Social support

Participants described the importance of social support as facilitating readiness to exercise. Several participants indicated that having someone to exercise with would improve their willingness to engage. Some participants elaborated on the benefit of social support from the PLWH community:

[Exercising] with other people that are going through the HIV, other people that are struggling with motivation, weak bodies, you know, so we kind of talk to each other, understand each other. (INT-7)

Some described how an HIV-specific exercise programme would facilitate their readiness by creating a safe and inclusive environment, eliminating the challenges associated with disclosure:

Disclosing is not easy. If you get somebody that doesn’t know and doesn’t like it. You’re screwed. Alienated. In front of the whole gym. There is still right now stigma. (INT-5)

Perceptions and beliefs

Participants indicated that their readiness to engage in exercise were influenced by their perceptions and beliefs about exercise, often expressed through the prioritisation and perceived risks of exercise. One participant described how complexity and uncertainty made it difficult to prioritise exercise:

There are different priorities being placed around, and exercise is there, but if there’s a health crisis, sometimes it [exercise] can't be a number one priority that it should be. (INT-1)

Some participants described exercise as part of self-care such as eating, personal hygiene and sleeping. For others, exercising was a low priority, despite expressing knowledge that exercise was something they ‘should’ be doing:

[On my list of priorities exercise is] pretty low […] I don't think about it often to be honest. I should, but I don't […] Exercise would be last, I think. (INT-12)

Overall, the complex and episodic nature of HIV and multimorbidity can result in physical challenges and uncertainty that make exercising a potentially risky endeavour. Several participants expressed perceived risks associated with engaging in exercise, including fear of falling and overexertion leading to illness and fatigue:

Those are the kind of things that pop into my head [regarding exercise] […] am I going to hurt myself, how am I going to feel after, is it going to decimate me for the rest of the day? (INT-11)

Experience with exercise

Participants reported diversity in their experiences with physical activity, ranging from walking to a previous nationally ranked athlete. The impact of these experiences on participants’ readiness to engage was dependent on the positive or negative nature of past experiences. For one participant, having positive experiences with exercise was associated with increased sense of ability and readiness to engage in the future:

It's the feeling of accomplishment that helps fight the depression that makes you not want to [exercise]. And gives you the ability to see, yes I can do this, it is achievable, and I can take the next step. (INT-1)

Another participant described a negative experience that deterred him from continuing to exercise in a public facility:

These men kept hitting on me all the time, especially in the showers and the locker rooms, you know, I got tired of it so I stopped going. (INT-7)

For some, initial exposure to exercise occurred through the healthcare system during periods of health crises. One participant described how education through physiotherapy improved his readiness to engage in exercise:

Education is […] a very important part [of readiness][…]I know for me, through my various physiotherapies I was taught, I was educated, […] I saw the benefits. (INT-1)

However, not all participants received education through the healthcare system:

My doctors never talk to me about [exercise]. It's kind of odd, eh? Never. (INT-12)

Accessibility

When describing the conditions that influenced readiness to engage in exercise, most participants expressed the importance of accessibility. For some, a perceived lack of financial accessibility created obstacles to engagement and hindered their readiness to exercise:

[Gyms] cost money. Many of us are on very limited incomes. And […] simply cannot afford […] the gym […] you sit at home and you want to do something but you have no money so you can’t take the bus to get there […], so accessibility is very important. (INT-1)

For those with mobility restrictions stemming from HIV and multimorbidity, physical accessibility (or lack thereof) influenced readiness to engage in exercise:

I still get scared though going to the gym on my own […] cause there's no lockers for people with wheelchairs […] [the gym] has a staircase to get into the aqua fit pool. I can't do the staircase. (INT-11)

Collectively, the influence of social support, perceptions and beliefs, experiences with exercise and accessibility on readiness to exercise was regulated by the health-related consequences of the complex and episodic nature of HIV and multimorbidity.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first qualitative study to explore readiness to exercise among PLWH who live with multimorbidity. Participants described a range of perspectives regarding readiness to engage in exercise. We developed a Framework to conceptualise readiness as a dynamic, fluctuating spectrum that is influenced (facilitated or hindered) by one key factor (the complex and episodic nature of HIV and multimorbidity) and four subfactors (social supports, perceptions and beliefs, experience with exercise, and accessibility) for PLWH and multimorbidity. The TTM that describes readiness to engage in behaviour change was used to inform our approach and inspired our conceptualisation of readiness as a spectrum.22 24 While this Framework was developed specifically for PLWH and multimorbidity, the salient factors identified within it may be applicable to those living with other chronic and episodic illnesses to better understand readiness to engage in exercise.32

Participants reported a median of nine comorbidities which may reflect the high levels of multimorbidity among PLWH associated with ageing with HIV and the long-term use of antiretroviral therapy.2 3 Some participants described that living with concurrent health conditions facilitated their exercise engagement, as it promoted a sense of overall well-being to counteract the impacts of living with multimorbidity. This finding challenges the notion of multimorbidity primarily acting as a barrier to exercise engagement.33 Future research may explore if the number, type and clusters of concurrent health conditions impact readiness to engage in exercise for PLWH.

Day-to-day challenges including physical impairments and pain played an important role in willingness and ability to exercise. Similar to the dimensions of disability experienced by PLWH, participants in this study expressed that complexity was exacerbated by the uncertainty of living with an episodic illness involving fluctuating and unpredictable periods of wellness.12 13 Participants voiced similar views to older adults who described the complexity of uncertainty of ageing, HIV and associated health challenges.34

Participants in this study described how their perceptions and beliefs about exercise (including the perceived risks associated with engaging in exercise) impacted their readiness. Similar perceptions including fear of exercise correlated negatively with physical activity levels among individuals with other chronic conditions.35 Social support and an inclusive environment positively influenced readiness to exercise, similarly found in the literature as factors that reduced fear of stigma and facilitated engagement in health-promoting behaviours for PLWH.36–38 Education and exercise history are important to exercise adherence for the general population and others living with chronic illness and comorbidity,38 39 suggesting educational programmes can help to improve engagement in health-promoting behaviours among PLWH and multimorbidity.35 39–41 Finally, financial constraints40 and inaccessibility of the exercise environment, such as difficulty using standard exercise equipment, were similarly documented as barriers to physical activity among people living with chronic conditions.42 43

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this study is the first to explore readiness to engage in exercise in a population now living with a growing number of concurrent health conditions. Our qualitative approach allowed for valuable insight to be drawn about the salient factors influencing readiness and facilitated the development of a Framework to demonstrate the interplay between these factors. We conducted a constant comparative analysis whereby data collection and analysis occurred concurrently. This enabled us to cease data collection after 14 interviews, the point which no new categories emerged from the data as they related to readiness to exercise.

Information regarding comorbidities was gathered through participant self-report and thus may either over-represent or under-represent concurrent health conditions experienced by participants.44 However, our intention was not to quantify complexity in this population, but rather to explore participants’ experiences living with HIV and multimorbidity using a qualitative approach. Future work may specifically determine how the number or type of comorbidities may influence readiness to exercise among PLWH.

Additionally, this study was conducted in an urban specialty HIV hospital. Results may not be broadly applicable to PLWH and multimorbidity in the broader community. Furthermore, it is unclear how these findings may transfer to the experiences of PLWH in rural settings or low-income countries. Future research should explore the concept of readiness to exercise in the developing context where there is an emerging role of exercise for PLWH with access to antiretroviral therapy.45 Further, additional factors, beyond those outlined in the Framework, may influence readiness to engage in exercise among PLWH and multimorbidity. Identifying such factors and their relationship to those in the Framework is an area for future research.

Implications for practice

Exploring readiness to engage in exercise among PLWH and multimorbidity is important for understanding and promoting engagement as a beneficial self-management strategy for PLWH.46 Although exercise can be effective and safe for PLWH,16–19 many are not meeting physical activity guidelines of engaging in 150 min of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity per week.20 47

To promote engagement in exercise, PLWH and healthcare providers should consider how factors influence readiness as articulated in the Framework. Opportunities exist for healthcare providers to educate and recommend exercise as a self-management strategy for PLWH and multimorbidity.48 49 Exercise recommendations can emphasise flexible and adaptable forms of engagement to account for fluctuations in health and address the complexity and uncertainty articulated by PLWH; models successfully employed by individuals with multiple sclerosis.50 51 Education from healthcare providers can focus on addressing perceptions and beliefs about exercise, including fear of physical injury and overexertion to help enhance physical activity among PLWH.

Conclusions

A diverse range of perceptions exist related to readiness to engage in exercise among PLWH and multimorbidity. Readiness to exercise is a dynamic and fluctuating construct that is primarily influenced by the health-related consequences of the complex and episodic nature of HIV and multimorbidity as well as social supports; perceptions and beliefs; experience with exercise; and accessibility. Healthcare providers should consider the interplay of these factors in order to enhance physical activity and subsequently improve overall health outcomes of PLWH and multimorbidity.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the participants for graciously offering their time to make this study possible as well as Casey House staff for assisting with recruitment and provision of interview space for this study. The authors acknowledge Ayesha Nayar for her assistance in this research. This research was completed in partial fulfillment of the requirements for an MScPT degree at the University of Toronto.

Footnotes

Contributors: KKO developed and planned the study with SCC. Both possess expertise in qualitative methodology, HIV and exercise research. KKO and SCC supervised AS, KV, DE, DK and PL. PJ, who possesses expertise in exercise and qualitative methodology, had an advisory role throughout. AS, KV, DE, DK and PL developed the protocol, collected and analysed the data as part of their involvement in the MScPT curriculum at the University of Toronto. AS, KV, DE, DK and PL (MScPT students) developed skills in qualitative research methodology including attending lectures; completing readings on qualitative research study design; understanding steps of recruitment, data collection and analysis; completing a literature review; developing the research protocol; interview guide and demographic questionnaire; and considering the ethical issues associated with this research. All steps were closely reviewed and guided by the advisors on the team (KKO, SCC, PJ). All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This research was funded by a Connaught New Researcher Award at the University of Toronto. KKO is supported by a New Investigator Award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) (Funding Reference Number: MSH-122796).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: University of Toronto HIV/AIDS Research Ethics Board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Hasse B, Ledergerber B, Furrer H et al. Morbidity and aging in HIV-infected persons: the Swiss HIV cohort study. Clin Infect Dis 2011;53:1130–9. 10.1093/cid/cir626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kendall CE, Wong J, Taljaard M et al. A cross-sectional, population-based study measuring comorbidity among people living with HIV in Ontario. BMC Public Health 2014;14:161 10.1186/1471-2458-14-161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guaraldi G, Silva AR, Stentarelli C. Multimorbidity and functional status assessment. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2014;9:386–97. 10.1097/COH.0000000000000079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guaraldi G, Orlando G, Zona S et al. Premature age-related comorbidities among HIV-infected persons compared with the general population. Clin Infect Dis 2011;53:1120–6. 10.1093/cid/cir627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Justice AC. HIV and aging: time for a new paradigm. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2010;7:69–76. 10.1007/s11904-010-0041-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fortin M, Lapointe L, Hudon C et al. Multimorbidity is common to family practice: is it commonly researched? Can Fam Physician 2005;51:244–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edmiston N, Passmore E, Smith DJ et al. Multimorbidity among people with HIV in regional New South Wales, Australia. Sex Health 2015;12:425–32. 10.1071/SH14070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rusch M, Nixon S, Schilder A et al. Impairments, activity limitations and participation restrictions: prevalence and associations among persons living with HIV/AIDS in British Columbia. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2004;2:46 10.1186/1477-7525-2-46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siegel K, Lekas HM. AIDS as a chronic illness: psychosocial implications. AIDS 2002;16(Suppl 4):S69–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Myezwa H, Stewart A, Musenge E et al. Assessment of HIV-positive in-patients using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) at Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital, Johannesburg. Afr J AIDS Res 2009;8:93–105. 10.2989/AJAR.2009.8.1.10.723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Myezwa H, Buchalla CM, Jelsma J et al. HIV/AIDS: use of the ICF in Brazil and South Africa—comparative data from four cross-sectional studies. Physiotherapy 2011;97:17–25. 10.1016/j.physio.2010.08.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Brien KK, Bayoumi AM, Strike C et al. Exploring disability from the perspective of adults living with HIV/AIDS: development of a conceptual framework. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2008;6:76 10.1186/1477-7525-6-76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O'Brien KK, Davis AM, Strike C et al. Putting episodic disability into context: a qualitative study exploring factors that influence disability experienced by adults living with HIV/AIDS. J Int AIDS Soc 2009;12:5 10.1186/1758-2652-2-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Swendeman D, Ingram BL, Rotheram-Borus MJ. Common elements in self-management of HIV and other chronic illnesses: an integrative framework. AIDS Care 2009;21:1321–34. 10.1080/09540120902803158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holman H, Lorig K. Patient self-management: a key to effectiveness and efficiency in care of chronic disease. Public Health Rep 2004;119:239–43. 10.1016/j.phr.2004.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O'Brien K, Nixon S, Tynan AM et al. Aerobic exercise interventions for adults living with HIV/AIDS. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;(8):CD001796 10.1002/14651858.CD001796.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O'Brien K, Tynan AM, Nixon S et al. Effects of progressive resistive exercise in adults living with HIV/AIDS: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. AIDS Care 2008;20:631–53. 10.1080/09540120701661708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gomes-Neto M, Conceição CS, Oliveira Carvalho V et al. A systematic review of the effects of different types of therapeutic exercise on physiologic and functional measurements in patients with HIV/AIDS. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2013;68:1157–67. 10.6061/clinics/2013(08)16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gomes Neto M, Ogalha C, Andrade AM et al. A systematic review of effects of concurrent strength and endurance training on the health-related quality of life and cardiopulmonary status in patients with HIV/AIDS. Biomed Res Int 2013;2013:319524 10.1155/2013/319524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schuelter-Trevisol F, Wolff FH, Alencastro PR et al. Physical activity: do patients infected with HIV practice? How much? A systematic review. Curr HIV Res 2012;10:487–97. 10.2174/157016212802429794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lindsay-Reid E, Osborn RW. Readiness for exercise adoption. Soc Sci Med Med Psychol Med Sociol 1980;14:139–46. 10.1016/0160-7979(80)90027-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Basta TB, Reece M, Wilson MG. The transtheoretical model and exercise among individuals living with HIV. Am J Health Behav 2008;32:356–67. 10.5555/ajhb.2008.32.4.356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marshall SJ, Biddle SJ. The transtheoretical model of behavior change: a meta-analysis of applications to physical activity and exercise. Ann Behav Med 2001;23:229–46. 10.1207/S15324796ABM2304_2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Health Promot 1997;12:38–48. 10.4278/0890-1171-12.1.38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health 2000;23:334–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sandelowski M. What's in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Res Nurs Health 2010;33:77–84. 10.1002/nur.20362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stewart A, Chan Carusone S, To K et al. Causes of death in HIV patients and the evolution of an AIDS hospice: 1988–2008. AIDS Res Treat 2012;2012:390406 10.1155/2012/390406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O'Brien K, Solomon P, Worthington C et al. Comparison of comorbidities among adults living with HIV in Canada by age group: results from the HIV Health and Rehabilitation Survey. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol 2015;26(Suppl B):28B. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marcus BH, Simkin LR. The transtheoretical model: applications to exercise behavior. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1994;26:1400–4. 10.1249/00005768-199411000-00016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kvale S, Brinkmann S. Interviews: learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing. Sage, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lublin FD, Reingold SC. Defining the clinical course of multiple sclerosis: results of an international survey. National Multiple Sclerosis Society (USA) Advisory Committee on Clinical Trials of New Agents in Multiple Sclerosis. Neurology 1996;46:907–11. 10.1212/WNL.46.4.907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lim K, Taylor L. Factors associated with physical activity among older people—a population-based study. Prev Med 2005;40:33–40. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.04.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Solomon P, O'Brien K, Wilkins S et al. Aging with HIV and disability: the role of uncertainty. AIDS Care 2014;26:240–5. 10.1080/09540121.2013.811209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morgan AD, Peck DF, Buchanan DR et al. Effect of attitudes and beliefs on exercise tolerance in chronic bronchitis. BMJ (Clin Res Ed) 1983;286:171–3. 10.1136/bmj.286.6360.171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Solomon P, Wilkins S. Participation among women living with HIV: a rehabilitation perspective. AIDS Care 2008;20:292–6. 10.1080/09540120701660320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Capili B, Anastasi JK, Chang M et al. Barriers and facilitators to engagement in lifestyle interventions among individuals with HIV. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care 2014;25:450–7. 10.1016/j.jana.2014.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roos R, Myezwa H, van Aswegen H. “Not easy at all but I am trying”: barriers and facilitators to physical activity in a South African cohort of people living with HIV participating in a home-based pedometer walking programme. AIDS Care 2015;27:235–9. 10.1080/09540121.2014.951309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rhodes RE, Martin AD, Taunton JE et al. Factors associated with exercise adherence among older adults. An individual perspective. Sports Med 1999;28:397–411. 10.2165/00007256-199928060-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith SR, Rublein JC, Marcus C et al. A medication self-management program to improve adherence to HIV therapy regimens. Patient Educ Couns 2003;50:187–99. 10.1016/S0738-3991(02)00127-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lorig KR, Sobel DS, Stewart AL et al. Evidence suggesting that a chronic disease self-management program can improve health status while reducing hospitalization: a randomized trial. Med Care 1999;37:5–14. 10.1097/00005650-199901000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bayliss EA, Steiner JF, Fernald DH et al. Descriptions of barriers to self-care by persons with comorbid chronic diseases. Ann Fam Med 2003;1:15–21. 10.1370/afm.4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Becker H, Stuifbergen A. What makes it so hard? Barriers to health promotion experienced by people with multiple sclerosis and polio. Fam Community Health 2004;27:75–85. 10.1097/00003727-200401000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van den Akker M, van Steenkiste B, Krutwagen E et al. Disease or no disease? Disagreement on diagnoses between self-reports and medical records of adult patients. Eur J Gen Pract 2015;21:45–51. 10.3109/13814788.2014.907266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roos R, Myezwa H, van Aswegen H et al. Effects of an education and home-based pedometer walking program on ischemic heart disease risk factors in people infected with HIV: a randomized trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2014;67:268–76. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Worthington C, Myers T, O'Brien K et al. Rehabilitation in HIV/AIDS: development of an expanded conceptual framework. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2005;19:258–71. 10.1089/apc.2005.19.258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Garber CE, Blissmer B, Deschenes MR et al. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: guidance for prescribing exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2011;43:1334–59. 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318213fefb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wechsler H, Levine S, Idelson RK et al. The physician's role in health promotion—a survey of primary-care practitioners. N Engl J Med 1983;308:97–100. 10.1056/NEJM198301133080211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nixon S, Forman L, Hanass-Hancock J et al. Rehabilitation: a crucial component in the future of HIV care and support: opinion. South Afr J HIV Med 2011;12:12–17. [Google Scholar]

- 50.White LJ, Dressendorfer RH. Exercise and multiple sclerosis. Sports Med 2004;34:1077–100. 10.2165/00007256-200434150-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.White LJ, McCoy SC, Castellano V et al. Resistance training improves strength and functional capacity in persons with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2004;10:668–74. 10.1191/1352458504ms1088oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2015-010029supp1.pdf (357.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2015-010029supp2.pdf (265.7KB, pdf)