Abstract

Objective

South Korean police officers have a greater workload compared to their counterparts in advanced countries. However, few studies have evaluated the occupational challenges that South Korean police officers face. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the police officer's job characteristics and risk of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among South Korean police officers.

Design

Cross-sectional study.

Setting

Police officers in South Korea.

Participants

3817 police officers with a traumatic event over a 1-year period.

Main outcome measures

Officers with a response to the Impact of Event Scale (revised Korean version) score of ≥26 were classified as high risk, and we evaluated their age, sex, department and rank, as well as the frequency and type of traumatic events that they experienced.

Results

Among the respondents, 41.11% were classified as having a high risk of PTSD. From the perspective of the rank, Inspector group (46.0%) and Assistant Inspector group (42.7%) show the highest frequencies of PTSD. From the perspective of their working division, Intelligence and National Security Division (43.6%) show the highest frequency, followed by the Police Precinct (43.5%) and the Traffic Affairs Management Department (43.3%). It is shown that working in different departments was associated with the prevalence of PTSD (p=0.004).

Conclusions

The high-risk classification was observed in 41.11% of all officers who had experienced traumatic events, and this frequency is greater than that for other specialised occupations (eg, firefighters). Therefore, we conclude that groups with an elevated proportion of high-risk respondents should be a priority for PTSD treatment, which may help increase its therapeutic effect and improve the awareness of PTSD among South Korean police officers.

Keywords: MENTAL HEALTH, PUBLIC HEALTH

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Few studies have evaluated the occupational challenges that South Korean police officers face.

They have great workloads compared to their counterparts in advanced countries and they are assumed to be exposed to a high risk of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

This study included 3817 respondents, which is a much larger sample size than those in the previous South Korean and overseas studies.

What we found in this study was that among the respondents of 3817 policemen in the Republic of Korea, 41.11% were classified as having a high risk of PTSD and that this frequency is greater than that for other specialised occupations (eg, firefighters).

According to the results of our study, groups of Korean policemen who were high-risk respondents should be a priority for PTSD treatment, which may help increase its therapeutic effect and improve the awareness of PTSD among South Korean police officers.

Objective

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a type of anxiety disorder that involves a psychological response after experiencing a traumatic life-threatening event. In this context, trauma can be defined as damage to the psyche after overwhelming stress that exceeds one's ability to cope, and the American Psychiatric Association has recognised PTSD as a type of anxiety disorder since the 1980s.1–4 Furthermore, PTSD is a major anxiety disorder that frequently occurs among professionals who are exposed to traumatic events, such as military veterans, emergency medical technicians and firefighters, as well as people who have experienced large-scale disasters.5–7

Police officers are often the first emergency personnel to arrive at the scene of various crimes, such as murder, robbery, sexual abuse and suicide. This exposure increases their risk of injury or witnessing the injury of their colleagues, compared to the general population. Therefore, police officers perform a high-risk job that carries a high risk of experiencing PTSD.8

In 2012, South Korea had 102 386 police officers, with an average age of 41.8 years.9 In 2010, there were 8549, 511 police emergency calls, while in 2011there were 9 951 202 police emergency calls, which corresponds to a 16.4% increase. Furthermore, the number of reported cases is increasing every year.10 In contrast, the police force's annual growth rate has been approximately 1% since 2000, and each South Korean police officer serves approximately 498 people. Other developed countries have a much lower ratio, with each police officer serving approximately 351 persons in the USA, 347 persons in France and 320 persons in Germany. Therefore, these data indicate that South Korea is experiencing a shortage of police officers.11 The most recent study that analysed the relationship between the policemen who had experienced traumatic events and the symptoms of PTSD was reported in Germany. In this study, the frequency of PTSD symptoms of German police officers was closely related to that of those who had experienced traumatic events.12 The prevalence of PTSD in the general population is approximately 3–6%.13 In addition, PTSD can occur in any age group. Furthermore, the most common symptoms of PTSD are falling into a state of panic after recurring flashbacks of the traumatic event, insomnia and avoidance.2 However, very few PTSD studies have dealt with a police officers’ case. Therefore, the present study was conducted among South Korean police officers, in order to determine the severity of their PTSD, and evaluated the relationship with age, sex, rank and department. Using this information, we hope to further our understanding of PTSD among police officers and its organisational characteristics.

Methods

This study used the Impact of Event Scale (revised Korean version; IES-R-K) questionnaire as a part of a ‘Police Officer Stress Survey’ that was conducted by the Korea National Police Agency among active police officers during August 2012. That survey was administered via the police intranet and responses were received from 20 780 officers; the present study evaluated secondary data from that survey.

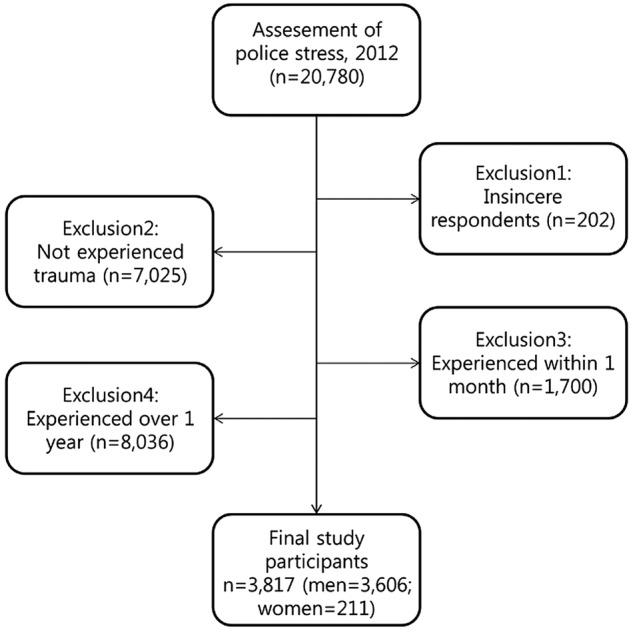

Among the responses, we excluded 202 incomplete surveys, 7025 responses from officers who indicated that they had not experienced a traumatic event, and 1700 responses from officers who had experienced a traumatic event within 1 month (these responses did not meet the criteria for PTSD). Furthermore, we excluded 8036 responses that indicated that the traumatic event had been experienced >1 year before the survey, as our goal was to evaluate data that reflected the current departmental characteristics of active officers. Therefore, this study evaluated data from 3817 responses (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram depicting study population.

The survey included questions regarding age, sex, rank and department, as well as three questions that were used to identify whether the respondent had experienced a traumatic event. These three questions evaluated the respondent's experience with a firearm, direct experience of a traumatic event and witnessing of a traumatic event. Indirect trauma means a case where the participant witnessed the event; on the other hand, direct trauma means a case where the participant him/herself experienced the event.

If the respondent answered ‘yes’ to any of the three questions, they were asked to complete the IES-R-K questionnaire. The original IES questionnaire was developed by Horowitz to study the process of adjustment among burn patients, and is now widely used to identify persons who have a high risk of PTSD. The original questionnaire has been translated into Korean and has been tested to confirm its validity.14–16 To identify respondents with a high risk of PTSD, the 22 questions of the IES-R-K questionnaire were assigned a score of 0–4; respondents with a total score of ≥26 were classified as high risk.17

All analyses were performed using SAS software (V.9.3; SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina, USA). The χ2 test was used to evaluate the age, sex, department, rank and frequency and type of traumatic event experienced by the reference group and the other groups. We also used logistic regression by grade and department.

Results

The general characteristics of the respondents are listed in table 1. Regarding age, 1574 officers were in their 40s (41.24%), 1237 officers were in their 30s (32.41%), 709 officers were in their 50s (18.57%) and 297 were in their 20s (7.78%). The majority of respondents were men (n=3606; 94.47%), and only 211 women (5.53%) were included.

Table1.

Basic characteristics of study population according to trauma experience and experience period

| Category of trauma experience |

Experience period |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Character | Shooting experience | Direct trauma | Indirect trauma | 1–6 months | 6–12 months | Total |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| 20–29 | 2 (0.05) | 173 (4.53) | 122 (3.20) | 181 (4.74) | 116 (3.04) | 297 (7.78) |

| 30–39 | 24 (0.63) | 891 (23.34) | 322 (8.44) | 655 (17.16) | 582 (15.25) | 1237 (32.41) |

| 40–49 | 109 (2.86) | 1204 (31.54) | 261 (6.84) | 910 (23.84) | 664 (17.40) | 1574 (41.24) |

| Over 50s | 57 (1.49) | 493 (12.92) | 159 (4.17) | 400 (10.48) | 309 (8.10) | 709 (18.57) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Man | 189 (4.95) | 2659 (69.66) | 758 (19.86) | 2046 (53.60) | 1560 (40.87) | 3606 (94.47) |

| Woman | 3 (0.08) | 102 (2.67) | 106 (2.78) | 100 (2.62) | 111 (2.91) | 211 (5.53) |

| Department of work | ||||||

| Police Administration Department | 3 (0.08) | 77 (2.02) | 30 (0.79) | 30 (0.79) | 80 (2.10) | 110 (2.88) |

| Public Security Department | 4 (0.10) | 104 (2.72) | 24 (0.63) | 48 (1.26) | 84 (2.20) | 132 (3.46) |

| Traffic Affairs Management Department | 18 (0.47) | 223 (5.84) | 59 (1.55) | 166 (4.35) | 134 (3.51) | 300 (7.86) |

| Investigation Department | 11 (0.29) | 191 (5.00) | 61 (1.60) | 113 (2.96) | 150 (3.93) | 263 (6.59) |

| Detective Division | 23 (0.60) | 243 (6.37) | 89 (2.33) | 224 (5.87) | 131 (3.43) | 355 (9.30) |

| Police Precinct | 90 (2.36) | 1223 (32.04) | 344 (9.01) | 1040 (27.25) | 617 (16.16) | 1657 (43.41) |

| Intelligence and National Security Division | 3 (0.08) | 64 (1.68) | 11 (0.29) | 28 (0.73) | 50 (1.31) | 78 (2.04) |

| Riot Police Company | 1 (0.03) | 34 (0.89) | 23 (0.60) | 23 (0.60) | 35 (0.92) | 58 (1.52) |

| Office of Inspection & Public Complaints | 0 (0.00) | 21 (0.55) | 12 (0.31) | 14 (0.37) | 19 (0.50) | 33 (0.86) |

| Public Safety Department | 39 (1.02) | 581 (15.22) | 211 (5.53) | 460 (12.05) | 371 (9.72) | 831 (21.77) |

| Grade | ||||||

| Police Officer | 6 (0.16) | 416 (10.90) | 242 (6.34) | 396 (10.37) | 268 (7.02) | 664 (17.40) |

| Senior Police Officer | 10 (0.26) | 398 (10.43) | 127 (3.330 | 278 (7.28) | 257 (6.73) | 535 (14.02) |

| Assistant inspector | 100 (2.62) | 1187 (31.10) | 254 (6.65) | 874 (22.90) | 667 (17.47) | 1541 (40.37) |

| Inspector | 67 (1.76) | 673 (17.63) | 198 (5.19) | 526 (13.78) | 412 (10.79) | 938 (24.57) |

| Senior inspector | 9 (0.24) | 78 (2.04) | 33 (0.86) | 64 (1.68) | 56 (1.47) | 120 (3.14) |

| Over Superintendent | 0 (0.00) | 9 (0.24) | 10 (0.26) | 8 (0.21) | 11 (0.29) | 19 (0.50) |

| Total | 192 (5.03) | 2761 (72.33) | 864 (22.64) | 2146 (56.22) | 1671 (43.78) | 3817 (100.00) |

The Police Precinct had the greatest number of respondents (n=1657; 43.41%). The Public Safety Department had 831 respondents (21.77%), the Detective Division had 355 respondents (9.30%), the Investigation Department had 263 respondents (6.89%), the Traffic Affairs Management Department had 300 respondents (7.86%), the Public Security Department had 132 respondents (3.46%) and the Police Administration Department had 110 respondents (2.88%). The Intelligence and National Security Division had 78 respondents (2.04%), the Riot Police Company had 58 respondents (1.52%), and the Office of Inspection & Public Complaints had 33 respondents (0.86%). This study included 1541 Assistant Inspectors (40.37%), 938 Inspectors (24.57%), 664 police officers (17.40%), 535 senior police officers (14.02%) and 120 senior Inspectors (3.14%). Only 19 respondents held a rank at or above the level of Superintendent.

The majority of respondents had experienced a direct traumatic event (n=2761), 864 respondents had experienced an indirect traumatic event and 192 respondents had been involved in a shooting. Experience with a firearm (2.86%) and an experience of a direct traumatic event (31.54%) were most common among respondents who were in their 40s, and an experience of an indirect traumatic event was most common among respondents in their 30s (8.44%). Male officers reported 189 cases involving firearm usage, and only three cases involving firearm usage were reported among female officers. Men were more likely to experience both a direct traumatic event (69.66%) and an indirect traumatic event (19.86%).

The Police Precinct reported the highest frequency of being involved in a shooting (2.36%), and the Public Safety Department reported the next highest frequency (1.02%). In addition, the Police Precinct had the most frequent exposure to a direct traumatic event (32.04%), and the Public Safety Department reported the next highest frequency (15.22%). Furthermore, the Police Precinct reported the highest frequency of an indirect traumatic event (9.01%) and the Public Safety Department reported the next highest frequency (5.53%). Assistant Inspectors and Inspectors reported the highest frequencies of being involved in a shooting (2.62% and 1.76%, respectively). Similarly, Assistant Inspectors and Inspectors reported the most frequent exposure to a direct traumatic event (31.10% and 17.63%, respectively; table 1).

When we evaluated the timing of these traumatic event experiences, 2146 respondents (56.22%) reported experiencing a traumatic event during the past 1–6 months, and 1671 respondents (43.78%) reported experiencing a traumatic event during the past 6–12 months. When we evaluated respondents who scored ≥26 on the IES-R-K (n=1569; 41.11%), the high-risk classification was most common among respondents who were in their 50s (48.38%) and 40s (43.4%). In contrast, the high-risk classification was observed in 29.51% of respondents who were in their 30s and in 27.61% of respondents who were in their 20s. This difference was statistically significant (p<0.001).

The Police Precinct had the greatest proportion of high-risk respondents (45.95%), and 43.59% of the Intelligence and National Security Division respondents were classified as high risk. The proportions of high-risk respondents were 43.33% in the Traffic Affairs Management Department, 42.24% in the Public Safety Department, 37.46% in the Detective Division, 36.50% in the Investigation Department, 34.09% in the Public Security Department, 33.33% in the Office of Inspection & Public Complaints, 29.31% in the Riot Police Company and 28.18% in the Police Administration Department. These differences were statistically significant (p=0.004).

Inspectors were the most likely to be classified as high risk (45.95%), and 42.7% of Assistant Inspectors were classified as high risk. The proportions of high-risk respondents were 41.12% among senior police officers, 35.83% among senior Inspectors, 32.23% among police officers and 16.67% among respondents with a rank of superintendent or higher. These differences were statistically significant (p<0.001; table 2).

Table2.

Basic characteristics of study population according to risk of PTSD

| Character | High-risk PTSD | Normal and low-risk PTSD | Total | p Value† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||||

| 20–29 | 82 (27.61) | 215 (72.39) | 297 (100.0) | <0.001* |

| 30–39 | 463 (37.43) | 774 (62.57) | 1237 (100.0) | |

| 40–49 | 681 (43.27) | 893 (56.73) | 1574 (100.0) | |

| Over 50s | 343 (48.38) | 366 (51.62) | 709 (100.0) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Man | 1480 (41.04) | 2126 (58.96) | 3606 (100.0) | 0.106 |

| Woman | 89 (42.18) | 122 (57.82) | 211 (100.0) | |

| Department of work | ||||

| Police Administration Department | 31 (28.18) | 79 (71.82) | 110 (100.0) | 0.004* |

| Public Security Department | 45 (34.09) | 87 (65.91) | 132 (100.0) | |

| Traffic Affairs Management Department | 130 (43.33) | 170 (56.67) | 300 (100.0) | |

| Investigation Department | 96 (36.50) | 167 (63.50) | 263 (100.0) | |

| Detective Division | 133 (37.46) | 222 (62.54) | 355 (100.0) | |

| Police Precinct | 721 (43.51) | 936 (56.49) | 1657 (100.0) | |

| Intelligence and National Security Division | 34 (43.59) | 44 (56.41) | 78 (100.0) | |

| Riot Police Company | 17 (29.31) | 41 (70.69) | 58 (100.0) | |

| Office of Inspection & Public Complaints | 11 (33.33) | 22 (66.67) | 33 (100.0) | |

| Public Safety Department | 351 (42.24) | 480 (57.76) | 831 (100.0) | |

| Grade | ||||

| Police Officer | 214 (32.23) | 450 (67.77) | 664 (100.0) | <0.001* |

| Senior Police Officer | 220 (41.12) | 315 (58.88) | 535 (100.0) | |

| Assistant inspector | 658 (42.70) | 883 (57.30) | 1541 (100.0) | |

| Inspector | 431 (45.95) | 507 (54.05) | 938 (100.0) | |

| Senior inspector | 43 (35.83) | 77 (64.17) | 120 (100.0) | |

| Over Superintendent | 3 (15.79) | 16 (84.21) | 19 (100.0) | |

| Total | 1569 (41.11) | 2248 (58.89) | 3817 (100.0) | |

*p Value: <0.05.

†p Value by χ2 test.

PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

The department expected to have a higher OR according to the above department task is investigation, detective, traffic affairs, Police Precinct, task force and Public Safety. However, the results of the actual analysis shows that ORs for Traffic Affairs Management Department, Police Precinct, Public Safety are significantly increased for police administration investigation, detective and task force and for information security department. After adjustment for gender, age and class, the highest OR was Traffic Affairs Management Department (OR 1.92) followed by intelligence and national security departments (OR 1.90) (table 3).

Table 3.

Association between grade, department and high risk of PTSD

| Crude OR |

Adjusted OR |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI |

| Grade | ||||

| Police Officer | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Senior Police Officer | 1.46* | 1.15 to 1.86 | 1.56* | 1.23 to 1.99 |

| Assistant inspector | 1.56* | 1.29 to 1.89 | 1.69* | 1.38 to 2.06 |

| Inspector | 1.78* | 1.45 to 2.19 | 1.91* | 1.54 to 2.37 |

| Senior inspector | 1.17 | 0.78 to 1.76 | 1.24 | 0.82 to 1.87 |

| Over Superintendent | 0.39 | 0.11 to 1.36 | 0.42 | 0.12 to 1.48 |

| Department† | ||||

| Police Administration Department | 1.00 | |||

| Public Security Department | 1.31 | 0.76 to 2.28 | 1.24 | 0.71 to 2.16 |

| Traffic Affairs Management Department | 1.94* | 1.21 to 3.12 | 1.88* | 1.17 to 3.03 |

| Investigation Department | 1.46 | 0.90 to 2.37 | 1.43 | 0.88 to 2.33 |

| Detective Division | 1.52 | 0.95 to 2.43 | 1.43 | 0.89 to 2.29 |

| Police Precinct | 1.96* | 1.28 to 3.00 | 1.92* | 1.25 to 2.94 |

| Intelligence and National Security Division | 1.96* | 1.06 to 3.62 | 1.90* | 1.03 to 3.50 |

| Riot Police Company | 1.05 | 0.52 to 2.13 | 1.00 | 0.49 to 2.02 |

| Office of Inspection & Public Complaints | 1.27 | 0.55 to 2.93 | 1.27 | 0.55 to 2.94 |

| Public Safety Department | 1.86* | 1.20 to 2.88 | 1.78* | 1.15 to 2.76 |

Adjusted by gender, age.

*p<0.05.

PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

Discussion

Overseas studies of PTSD have used the IES to analyse the proportion of individuals who have a high risk of PTSD after experiencing a traumatic event. For example, those studies have found that 22.2% of American firefighters and 17.3% of Canadian firefighters have a high risk of PTSD.18 19 South Korean research also found that 20 (13.7%) of 146 surveyed firefighters in Seoul had a high risk of PTSD.20 In contrast, a 2007 survey of active South Korean police officers revealed that 33.3% of respondents had a high risk of PTSD (using the IES).21 In this study, we used the IES-R-K to evaluate the proportion of police officers who had a high risk of PTSD, and found that 41.11% of the respondents were classified as high risk. This proportion is similar to, or higher than, the proportion of high-risk persons who were involved in other large-scale disasters or events, such as the 9/11 terrorist attack, the Kobe earthquake in Japan or the Tokyo subway sarin attack.6 15

In South Korea, the official police divisions are the Police Administration Department, the Public Security Department, the Traffic Affairs Management Department, the Investigation Department, the Detective Division, the Police Precinct, the Intelligence and National Security Division, the Riot Police Company, the Office of Inspection & Public Complaints and the Public Safety Department.22 The following divisions contained a relatively high proportion of respondents in the high-risk category: the Traffic Affairs Department, the Police Precinct, the Intelligence and National Security Division and the Public Safety Department. Interestingly, the duties of officers in the Intelligence and National Security Division are typically office-related. In this case, the probability of experiencing a traumatic event during normal working conditions appears to be low. However, officers in the division occasionally deployed for the site of demonstration. It is possible that these employees experience a more severe traumatic event during their deployments at the spot where the violence occurs.

Only 30% of the respondents from the Investigation Department and Detective Division were classified as high risk, which was unexpected, as these departments had been assumed to have a high proportion of PTSD. This discrepancy may be due to the nature of our cross-sectional data, which only evaluated a traumatic event during a 1-year period. Therefore, these data may be inadequate to analyse the cumulative effects of traumatic event exposure comprehensively, which may explain that unexpected finding. In contrast, officers from the Police Precinct, the Public Safety Department and the Traffic Affairs Management Department often experience both direct and indirect traumatic events, and this exposure most likely explains the relatively high proportion of individuals with a high risk of PTSD in those departments.

The Department of Police Administration is set as the reference group because the department is responsible for clerical duties. Traffic Affairs Department, Police Precinct department, Information Security and Public Safety Department showed higher ORs in comparison with Police Administration Department. In Korea, nearly every police unit, especially a police station, is officially divided into Police Administration, Public Security, Traffic Affairs, Investigation, Detective, Police Precinct, Intelligence and National security, Task force, Office of Inspection & Public Complaints and Public Safety Department.

If the role of each department is simply summarised, the Police Administration Department is conducting the matter related to service code or security and personnel, police information service and routine work, such as clerical work. The Public Security Department takes charge of the work of Public Security related to the election, operation and management of the mobile task force and security patrol, public security planning and supervision, escorts VIP from other country and former president guard and so on. The Traffic Affairs Management Department implements traffic enforcement, traffic management and license-related tasks such as reissuing of driver’s license or traffic accident investigation services. The Investigation Department performs the planning or managing of criminal crackdown, registration of the incident, criminal investigation and forensic investigation. The Detective department deals with tasks such as homicide, violence, forensic identification and drug crime. The Police Precinct takes charge of Police Precinct tasks, concerning mostly with the Patrol Division Unit. The Information Security Department deals with information technology security tasks and collects various information related to crime and demonstration scene. These police officers conduct the investigation of demonstrations scene, are committed to the scene alone and equipped with a radio and other device, without any weapon. The Task Force Team is responsible for the suppression of special situations and the Office of Inspection & Public Complaints deals with the inspection of the internal police corruption and audit. The Public Safety Department conducts the planning and administration of the Police Precinct administration and guidance, 112 patrol cars and security vehicles operation, 112 call control and management of related equipment.

This study has several limitations. The first limitation is that the reporting periods were defined as <1, 1–6, 6–12 and >12 months. Therefore, we cannot analyse data according to the acute phase (1–3 months) and chronic phase (>3 months) of PTSD. Nevertheless, although the distinction between the acute and chronic phases may be relevant for psychiatric analysis, previous research has demonstrated that this distinction does not affect the results for high-risk screening or score calculation. Furthermore, previous studies have evaluated the proportion of high-risk respondents using the IES, regardless of the PTSD period.23 24

The second limitation is that we did not evaluate various general respondent characteristics, including education, marital status, number of dispatches, smoking, physical fitness and alcohol consumption. Therefore, we cannot determine whether the risk of PTSD was associated with social support or lifestyle habits. However, previous studies that evaluated these general characteristics also performed separate analyses to determine the proportion of high-risk respondents. Therefore, an investigation of the respondents’ general characteristics is not a prerequisite for determining the work-related characteristics of PTSD,21 25 which was the aim of this study.

The third limitation is that this study is designed by the cross-sectional study and it may have recall bias due to self-reported outcomes.

This study also has several strengths. First, we used the IES-R-K questionnaire, which has been confirmed to be reliable and valid, despite its self-administered format.26 The use of this tool also ensures that our findings can be compared with those of other studies that used the revised IES or evaluated respondents for their risk of PTSD. Second, this study included 3817 respondents, which is a much larger sample size than those in the previous South Korean and overseas studies. This large sample size most likely enhances the reliability of our findings. Third, the national South Korean police force uses a departmental structure with standardised work assignments.27 Therefore, we believe that our departmental findings are applicable to the national South Korean police force.

In conclusion, we found that 41.1% of all police officers who had experienced a traumatic event were classified as having a high risk of PTSD, and this proportion is higher than that in other emergency services (eg, firefighters). This finding indicates that PTSD-related interventions and management are needed for police officers. In addition, we observed a relatively high proportion of high-risk respondents in the Intelligence and National Security Division. This finding was noticeable, given the office-based nature of that department's work and further research is needed to assess and validate that finding. Furthermore, we found that the Investigation Department and Detective Division had unexpectedly low proportions of high-risk respondents. This finding may be related to the cross-sectional nature of this study, and further studies are needed to evaluate the cumulative effect of PTSD in these departments. We believe that this study's findings can contribute to the treatment of PTSD, as they indicate that police officers should be recognised as a priority group that requires additional interventions and management. Furthermore, we believe that these findings will help raise the self-awareness of South Korean police officers regarding their vulnerability to the effects of trauma.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere thanks to the Department of Police Administration in Korea National Police Agency and its staff for their support and cooperation. Their support made it possible to implement this project.

Footnotes

Contributors: J-HL designed the study, collected and interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscript. IK suggested the study design, interpreted the data and revised the manuscript. J-UW suggested the study design, interpreted the data, and revised the manuscript. JR is the corresponding author of this article. He suggested the study design, interpreted the data and revised the manuscript. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the institutional review board of Yonsei University Graduate School of Public Health, Seoul, Korea (IRB: 2014-129).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Yehuda R. Post-traumatic stress disorder. N Engl J Med 2002;346:108–114.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Horowitz MJ, Wilner N, Kaltreider N et al. Signs and symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1980;37:85–92. 10.1001/archpsyc.1980.01780140087010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.First MB. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. DSM IV-4th edn APA, 1994:97–327. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davidson JR, Hughes D, Blazer DG et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder in the community: an epidemiological study. Psychol Med 1991;21:713–21. 10.1017/S0033291700022352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alexander DA, Klein S. Ambulance personnel and critical incidents: impact of accident and emergency work on mental health and emotional well-being. Br J Psychiatry 2001;178:76–81. 10.1192/bjp.178.1.76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galea S, Ahern J, Resnick H et al. Psychological sequelae of the September 11 terrorist attacks in New York City. N Engl J Med 2002;346:982–7. 10.1056/NEJMsa013404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolfe J, Schnurr PP, Brown PJ et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and war-zone exposure as correlates of perceived health in female Vietnam War veterans. J Consult Clin Psychol 1994;62:1235 10.1037/0022-006X.62.6.1235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Violanti JM, Paton D. Who gets PTSD? Issues of posttraumatic stress vulnerability. Charles C Thomas, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Korea National Police Statistical Yearbook. Korea: Korea National Police Agency, 2012:15–16.

- 10.Korea National Police Statistical Yearbook. Korea: Korea National Police Agency, 2012:92.

- 11.Korea National Police Statistical Yearbook: Korean National Police Agency, 2012:25.

- 12. doi: 10.1177/0886260515586358. Ellrich K, Baier D. Post-traumatic stress symptoms in police officers following violent assaults: a study on general and police-specific risk and protective factors. J Interpers Violence 2015; 0886260515586358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gradus JL. Epidemiology of PTSD. National Center for PTSD (United States Department of Veterans Affairs), 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu KK, Chan KS. The development of the Chinese version of Impact of Event Scale–Revised (CIES-R). Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2003;38:94–8. 10.1007/s00127-003-0611-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Asukai N, Kato H, Kawamura N et al. Reliabiligy and validity of the Japanese-language version of the impact of event scale-revised (Ies-RJ): four studies of different traumatic events. J Nerv Ment Dis 2002;190:175–82. 10.1097/00005053-200203000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sveen J, Low A, Dyster-Aas J et al. Validation of a Swedish version of the Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R) in patients with burns. J Anxiety Disord 2010;24:618–22. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.03.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lim HK, Woo JM, Kim TS et al. Reliability and validity of the Korean version of the Impact of Event Scale-Revised. Compr Psychiatry 2009;50:385–90. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Corneil W, Beaton R, Murphy S et al. Exposure to traumatic incidents and prevalence of posttraumatic stress symptomatology in urban firefighters in two countries. J Occup Health Psychol 1999;4:131 10.1037/1076-8998.4.2.131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Horowitz M, Wilner N, Alvarez W. Impact of Event Scale: a measure of subjective stress. Psychosom Med 1979;41: 209–18. 10.1097/00006842-197905000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kwon SC, Song J, Lee SJ et al. Posttraumatic stress symptoms and related factors in firefighters of a firestation. Korean J Occup Environ Med 2008;20:193–204. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sin SW. Levels and countermeasures of PTSD among police officers. J Korea Contents Assoc 2011;11:266–72. 10.5392/JKCA.2011.11.12.266 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Korea National Police Statistical Yearbook. Korea: Korea National Police Agency, 2012:396–7.

- 23.Stephens C, Long N. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the New Zealand police: the moderating role of social support following traumatic stress. Anxiety Stress Coping 1999;12:247–64. 10.1080/10615809908250477 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mann JP, Neece J. Workers’ compensation for law enforcement related post traumatic stress disorder. Behav Sci Law 1990;8:447–56. 10.1002/bsl.2370080410 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shin DY, Jeon MJ, Sakong J. Posttraumatic stress disorder and related factors in male firefighters in a metropolitan city. Korean J Occup Environ Med 2012;24:397–409. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eun HJ, Kwon TW, Lee SM et al. A study on reliability and validity of the Korean version of impact of event scale-revised. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc 2005;44:303–10. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moon B. The politicization of police in South Korea: a critical review. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management 2004;27:128–136. [Google Scholar]