Abstract

Objectives

The aims of the current study were to assess the prevalence of household cigarette gifting and sharing, and to evaluate the relationship between secondhand smoke (SHS) exposure, and cigarette gifting and sharing, in Zhejiang, China.

Design

A repeat cross-sectional design.

Setting

10 sites in 5 cities in Zhejiang, China.

Participants

Two surveys were conducted with adults in Zhejiang, China, in 2010 (N=2112) and 2012 (N=2279), respectively. At both waves, the same questionnaire was used; respondents were asked questions on residence, number of family smokers, indoor smoking rules, household income and cigarette gifting and sharing.

Results

The findings revealed that more than half of respondents’ families (54.50% in 2010, 52.79% in 2012) reported exposure to SHS. Many families (54.73% in 2010, 47.04% in 2012) shared cigarettes with others, and a minority (14.91% in 2010, 14.17% in 2012) reported their family giving cigarettes as a gift. There was a significant decrease in cigarette sharing from 2010 to 2012, irrespective of household with SHS exposure status; and the cigarette gifting was significantly decreased in household without SHS exposure.

Conclusions

Compared to households without SHS exposure, the prevalence of cigarette gifting and sharing in households with SHS exposure was more obvious. Encouraging and promoting a smoke-free household environment is necessary to change public smoking customs in Zhejiang, China.

Keywords: Secondhand smoke, cigarette gifting and sharing, cross-sectional study

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study in Zhejiang to assess the actual prevalence of household cigarette gifting and sharing among 18–59-year-olds.

There was a significant decrease in cigarette sharing from 2010 to 2012, irrespective of households with secondhand smoke (SHS) exposure status; and cigarette gifting was significantly decreased in households without SHS exposure.

The prevalence of cigarette gifting and sharing in households with SHS exposure is more obvious; encouraging and promoting a smoke-free household environment is necessary to change this custom.

The repeat cross-sectional design prohibits causal associations, and we rely on self-report measures, which may be subject to recall bias and social desirability.

The SHS exposure at home is relatively difficult to measure, and this study only used self-reporting to measure it, which potentially limits the findings.

Introduction

China is the world's largest consumer of tobacco products, with an estimated 301 million smokers.1 The annual number of death caused by tobacco use now exceeds 1 million and is expected to increase in the coming decades.2 Since the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control came into force in 2006, the Chinese government has focused attention on tobacco control and attempted to reduce its use by conducting programmes such as ‘Smoke-Free Olympics’3 and by passing smoke-free legislation.4 5 However, these tobacco control efforts have been hampered by the practices of gifting and sharing cigarettes, which are well accepted and pervasive across China.6

Smoking is a very common societal phenomenon in China. The sharing and gifting of cigarettes are parts of an extremely important social activity as they are perceived as conveying politeness to others.7 Compared to casual sharing of cigarettes, the formal gifting of cigarettes is more prevalent, especially during the Mid-Autumn Festival and Chinese New Year, as it shows respect for the recipient. Gifting and sharing cigarettes have become parts of Chinese custom, and they have become major detrimental factors by failing to motivate smokers to quit and increasing smoking among non-smokers.8–10

Zhejiang is a small province in China, with a developed economy and dense population. High SHS exposure at home (60.9%) and in public (65.3%) has been reported11 in Zhejiang, and the local government has implemented a number of tobacco control measures12 13 to reduce smoking in public. In the provincial capital city, Hangzhou, the municipality expanded a smoking ban to hospitals, kindergartens, schools, libraries and stadiums, in 2010. Local Centers for Disease Control printed the poster ‘Giving Cigarettes is Giving Harm’,14 which was disseminated across Zhejiang in 2011. They also launched a health promotion campaign, in 2012, making graphic warnings on cigarette packets mandatory, to educate smokers about the risks of smoking, which has been an effective approach.15 These campaigns provided knowledge about tobacco to the public, with the aim of building a health-first and people-oriented culture, and to create a non-smoking social atmosphere.

Although studies in China have indicated that the acts of gifting and sharing cigarettes are major contributors to China's high tobacco usage,9 there are few studies to quantitatively assess the prevalence of cigarette gifting and sharing. Such a study is urgently needed to assess the impact of this practice in China. We employed a repeat cross-sectional design and obtained representative data to assess the prevalence of cigarette gifting and sharing, through an in-depth analysis of data from the Tobacco Control China survey, regarding cigarette gifting and sharing.

Methods

Study design

Data came from The Epidemiology and Intervention Research for Tobacco Control in China.16 The baseline survey was conducted between May and October 2010, and a total of 2112 interviewees were included and interviews completed (effective rate 92.31%). The final survey was conducted between May and October 2012, and a total of 2279 interviewees were included and interviews completed (effective rate 93.02%). Fieldwork was conducted in Mandarin through face to face interviews with informed consent obtained from the respondents, and up to three visits per household were made to interview targeted individuals within that household. All survey interviewers and supervisors were trained by the Peking Union Medical College staff. The training sessions took place in small groups and were given by the same trainers to ensure consistency. Before the interview, mapping and listing were conducted by local Centers for Disease Control staff to identify selected households.

Participants

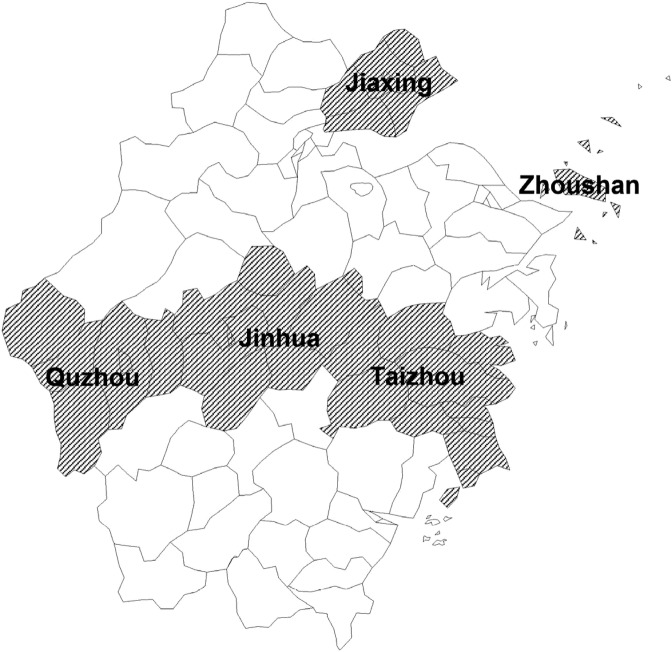

Cross-sectional samples of 18–59-year-olds were drawn from Zhejiang households by a multistage stratified cluster sampling design. The five regions were selected based on their geographic locations (see figure 1). In the first stage, each region was further divided into urban and rural areas, making 10 strata in total; urban districts or rural counties/county-level cities were selected, using a probability proportional to size (PPS) sampling method. In the second stage, each stratum was partitioned into several segments of around 50 households, and 6 segments were randomly selected from each stratum using the PPS method. In the third stage, every household in the selected segment was visited. Finally, one eligible household member 18–59 years old from each participating household was randomly sampled for an interview.

Figure 1.

The geographical distribution of the five regions in Zhejiang.

Variables

Cigarette gifting was a dependent variable used in this analysis and was measured by asking if respondents agreed with the following statements: ‘Did your family give cigarettes to others as a gift in the last year?’. Response categories were ‘yes’ and ‘no’.

Cigarette sharing was a dependent variable used in this analysis and was measured by asking if respondents agreed with the following statements: ‘Did your family share cigarettes with others in the last year?’. Response categories were ‘yes’ and ‘no’.

Relevant independent variables included in the analysis were obtained through self-report and were residence (urban, rural), number of family smokers (none, one smoker, two and more smokers) and indoor smoking rule (allowed, not allowed but exceptions, never allowed, no rules) and household income was measured by asking if respondents’ family had cars (one or more, none).

SHS exposure at home

In this study, SHS exposure at home was identified if a respondent reported anyone smoking inside his or her household at least once per month. The question ‘How often does anyone smoke inside your house?’ was used to evaluate the level of SHS exposure at home. A total of five options were available for this question, namely: Daily=1, Weekly=2, Monthly=3, More than monthly=4, Never=5. The respondents who selected 1, 2 or 3 were defined as their family experiencing SHS exposure.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using SPSS V.18.0. Logistic regression was conducted to examine differences in cigarette gifting and sharing by year, while controlling for potentially confounding variables. For each dependent variable (cigarette gifting and sharing), logistic regressions were run for the total sample and each SHS group (household with SHS exposure, household without SHS exposure). Each analysis compared responses in 2012 with 2010, controlling for residence, indoor smoking rules, household income and number of family smokers. Logistic regressions on the total sample were also controlled for household with SHS exposure status.

Ethics

Ethics approval was obtained from the Institute of Basic Medical Sciences of the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, and the Internal Review Boards at Zhejiang Center for Disease Control and Prevention (Hangzhou, China). In each household surveyed, the informed consent form was discussed with the participant, and signed by him or her, once they agreed to participate.

Results

General information

The study was conducted in 10 counties/county-level cities, and valid interviews were conducted with 2112 respondents in 2010, and 2279 respondents in 2012. Half of the respondents’ families (50.66% in 2010, 48.35% in 2012) came from urban settings. Many respondents’ families (40.06% in 2010, 46.42% in 2012) reported one smoker at home, and a significant minority had two and more smokers (7.01% in 2010, 8.69% in 2012). Only one-seventh of respondents’ families (13.92% in 2010, 16.85% in 2012) had no-smoking rules inside the house, and about one-fifth of respondents’ families (21.07% in 2010, 22.73% in 2012) had cars (details see table 1).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics of family, Survey (2010) and Survey (2012)

| 2010 |

2012 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic | N | Per cent | N | Per cent |

| Residence | ||||

| Urban | 1070 | 50.66 | 1102 | 48.35 |

| Rural | 1042 | 49.34 | 1177 | 51.65 |

| Family smoker amounts | ||||

| None | 1118 | 52.94 | 1023 | 44.89 |

| One smoker | 846 | 40.06 | 1058 | 46.42 |

| Two and more smokers | 148 | 7.01 | 198 | 8.69 |

| Indoor smoking rules | ||||

| Allowed | 792 | 37.50 | 796 | 34.93 |

| Not allowed, but exceptions | 494 | 23.39 | 522 | 22.90 |

| Never allowed | 294 | 13.92 | 384 | 16.85 |

| No rules | 532 | 25.19 | 577 | 25.32 |

| Households having cars | ||||

| One or more | 445 | 21.07 | 518 | 22.73 |

| None | 1667 | 78.93 | 1761 | 77.27 |

| Overall | 2112 | 2279 | ||

SHS exposure at home

Table 2 shows the level of SHS exposure at home, in 2010 and 2012. More than half of the respondents’ families (54.50% in 2010, 52.79% in 2012) reported exposure to SHS. The statistical analysis was of no significance (χ2=1.29, p>0.05). More than one-third of the respondents’ families (37.22% in 2010, 33.96% in 2012) were exposed to SHS almost daily.

Table 2.

SHS exposure at home, Survey (2010) and Survey (2012)

| How often does anyone smoke inside your home? | 2010 |

2012 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Per cent | N | Per cent | |

| Daily | 786 | 37.22 | 774 | 33.96 |

| Weekly | 204 | 9.66 | 275 | 12.07 |

| Monthly | 161 | 7.62 | 154 | 6.76 |

| More than monthly | 491 | 23.25 | 494 | 21.68 |

| Never | 470 | 22.25 | 582 | 25.54 |

| SHS | 1151 | 54.50 | 1203 | 52.79 |

SHS, secondhand smoke.

Cigarette gifting and sharing

The prevalence of cigarette gifting and sharing in households with SHS exposure was higher than that in households without SHS exposure (for details see table 3). Between 2010 and 2012, there was a significant decrease (54.73–47.04%) in household cigarette sharing (AOR=0.61, p<0.01), significantly for both household with SHS exposure (73.50% in 2010, 66.08% in 2012, AOR=0.56, p<0.01) and household without SHS exposure (32.26% in 2010, 25.74% in 2012, AOR=0.69, p<0.01).

Table 3.

Household cigarette gifting and sharing, Survey (2010) and Survey (2012)

| Total sample |

Household with SHS exposure |

Household without SHS exposure |

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cigarette gifting and sharing | Percentages |

Test of differences by year* |

Percentages |

Test of differences by year† |

Percentages |

Test of differences by year† |

||||||||||||

| 2010 |

2012 |

2010 |

2012 |

2010 |

2012 |

|||||||||||||

| N | Per cent | N | p Value | AOR | Per cent | N | Per cent | N | Per cent | AOR | p Value | N | Per cent | N | Per cent | AOR | p Value | |

| Cigarette sharing | 1156 | 54.73 | 1072 | 47.04 | 0.61 | <0.01 | 846 | 73.50 | 795 | 66.08 | 0.56 | <0.01 | 310 | 32.26 | 277 | 25.74 | 0.69 | <0.01 |

| Cigarette gifting | 315 | 14.91 | 323 | 14.17 | 0.92 | 0.32 | 214 | 18.59 | 232 | 19.29 | 1.01 | 0.90 | 101 | 10.51 | 91 | 8.46 | 0.73 | <0.05 |

*p Values are based on logistic regressions, testing differences 2012 vs 2010 after controlling for residence, indoor smoking rules, household income, family smoker amounts and household with SHS exposure status.

†p Values are based on logistic regressions, testing differences 2012 vs 2010 after controlling for residence, indoor smoking rules, household income and number of family smokers.

AOR, adjusted ORs; SHS, secondhand smoke.

Respondents reporting ‘their family give cigarettes to others as a gift’, were 14.91% and 14.17%, in 2010 and 2012, respectively, with no significant difference. There was no difference for household with SHS exposure (18.59% in 2010, 19.29% in 2012, AOR=1.01, p=0.90), but there was a significant difference in household without SHS exposure (10.51% in 2010, 8.46% in 2012, AOR=0.73, p<0.05).

Discussion

The present study, to the best of our knowledge, is the first to assess the prevalence of household cigarette gifting and sharing in Zhejiang, one of the most densely populated provinces in China (463.7/km2).17 The major findings of the current study include: (1) more than half of respondents’ families reported exposure to SHS, which shows no sign of slowing; (2) it seemed to be a downward trend for household cigarette sharing, but the proportion was still high (47% in 2012); (3) one of seven families gave cigarettes to others as a gift, a number that has held steady in recent years; and (4) the prevalence of cigarette gifting and sharing in households with SHS exposure was higher than that in households without SHS exposure.

Our previous research11 indicated that the SHS exposure at home in Zhejiang remained very serious. The household was the main place where women and children were exposed to SHS,18 19 and SHS remained in household air for a considerable period after a cigarette was smoked,20 which may adversely affected health. Therefore, we should engage in campaigns to create smoke-free households, and this may be particularly true in China.

As we know, cigarette gifting and sharing have influenced current tobacco control efforts in China, and strongly contributed to smoking initiation as well as failure to quit smoking among Chinese.8 9 The study revealed a significant decrease in cigarette sharing from 2010 to 2012, regardless of whether the household had SHS or not. This may be due to local government authorities implementing tobacco control practices, which was well accepted locally. Many smoke-free intervention programmes12 13 were conducted to make public places smoke-free. People have begun to reduce cigarette sharing before the external environment becomes smoke-free.

The findings indicated that cigarette gifting has remained unchanged in recent years, and the proportion was about one-seventh. Gifting cigarettes was most prevalent in China during the Mid-Autumn Festival and Chinese New Year,21 the proportion was 74% in Hunan22 and 67.9% in Jiangsu.23 And some previous studies24 25 also indicated that the prevailing cigarette gifting custom should be drastically changed. It is ubiquitous throughout the country, even as part of Chinese custom.9 We also started a mass media campaign called ‘Giving Cigarettes is Giving Harm’14 in 2011, which has helped fight the tobacco epidemic.26 However, it was not effective in Zhejiang. One possible interpretation might be the differences in the economy: Zhejiang is one of the traditional hubs for China’s private economy, and cigarette gifting plays an important role in economic activities.

This paper also found that the prevalence of cigarette gifting and sharing in households with SHS exposure was more obvious. As we know, the family is the cell of society, and the family environment is a microcosm of social environments. If we want to change the custom of cigarette gifting and sharing in China, we should encourage and promote smoke-free households first. For example, we could use mass media to highlight the high risks for women and children, which has been well-documented27 28 in the USA and India.

In terms of potential limitations, the repeat cross-sectional design prohibits causal associations, and we relied on self-report measures, which may be subject to recall bias and social desirability. The characteristics of the interviewee, such as age and gender, would induce the reporting bias, actually. We trained all the interviewers before field investigation, and reinforced quality control to improve the data quality and to reduce this bias. Household income could not be easily measured, therefore we used family car ownership to estimate household income, which has been shown to have a positive correlation between household income and car ownership in China.29 SHS exposure at home was also relatively difficult to measure, and this study only used self-reporting to measure it, which potentially limited the findings. Assessment would be better accomplished using a combination of several methods, such as self-reporting and indoor particulate matter 2.5 (fine particles 2.5 mm in diameter and smaller) level measurements.

Conclusion

In summary, a repeat cross-sectional study with multistage stratified cluster sampling was employed to study household cigarette gifting and sharing. The results showed that the prevalence of cigarette gifting and sharing in households with SHS exposure was more obvious, and this should encourage and promote smoke-free household environments to change public smoking customs in Zhejiang, China.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the Institute of Basic Medical Sciences at the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & School of Basic Medicine, China CDC and the local CDC representatives in each city, for their role in the field work and data collection.

Footnotes

Contributors: YX conceived and designed the experiments. YX analysed the data. SX, QW and YG contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools. YX wrote the paper. All the authors were actively and substantially involved in drafting the article and final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: This work was supported by a grant from the NIH project “Epidemiology and Intervention Research for Tobacco Control in China” (R01 RFA-TW-06-006).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Li Q, Hsia J, Yang GH. Prevalence of smoking in China in 2010. N Engl J Med 2011;364:2469–70. 10.1056/NEJMc1102459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang GH. Monitoring epidemic of tobacco use, promote tobacco control. Biomed Environ Sci 2010;23:420–1. 10.1016/S0895-3988(11)60001-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stewart E. IOC praises efforts to reduce air pollution in Beijing 2008. http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2008/aug/07/china.olympics2008 (accessed 25 Jun 2014).

- 4.China Daily Online. Chinese city spearheads national smoking ban 2010. http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2010-09/08/content_11275815.htm (accessed 25 Jun 2014).

- 5.World Health Organization. WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic 2013. http://www.who.int/tobacco/global_report/2013/report.pdf (accessed 25 Jun 2014).

- 6.Kohrman M. Depoliticizing tobacco's exceptionality: male sociality, death and memory-making among Chinese cigarette smokers. China J 2007;58:85–109. 10.1086/tcj.58.20066308 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tu SP, Walsh M, Tseng B et al. Tobacco use by Chinese American men: an exploratory study of the factors associated with cigarette use and smoking cessation. Asian Am Pac Isl J Health 2000;8:46–57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ding D, Hovell MF. Cigarettes, social reinforcement, and culture: a commentary on “Tobacco as a social currency: cigarette gifting and sharing in China.” Nicotine Tob Res 2012;14:255–7. 10.1093/ntr/ntr277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rich ZC, Xiao S. Tobacco as a social currency: cigarette gifting and sharing in China. Nicotine Tob Res 2012;14:258–63. 10.1093/ntr/ntr156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu M, Rich ZC, Luo D et al. Cigarette sharing and gifting in rural China: a focus group study. Nicotine Tob Res 2012;14:361–7. 10.1093/ntr/ntr262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu Y, WU QQ, Xu SY et al. Current research of passive smoking exposure in Zhejiang. Dis Surveill 2012;27:887–90.,897. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu Y, Zhang XW, Guo JX et al. Impact evaluation of tobacco use prevention program on middle school students in Zhejiang. Chinese J School Health 2007;28:418–20. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu Y, Wu QQ, Xu SY et al. Effectiveness evaluation of smoke-free intervention in 20 health institutions of Zhejiang province. Chinese J Health Educ 2011;27:563–7. [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Lung Foundation, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, & World Health Organization. Giving cigarettes is giving harm 2009. http://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/19/1.cover-expansion (accessed 25 Jun 2014).

- 15.Fong GT, Hammond D, Jiang Y et al. Perceptions of tobacco health warnings in China compared with picture and text-only health warnings from other countries: an experimental study. Tob Control 2010;19(Suppl 2):i69–77. 10.1136/tc.2010.036483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wan X, Stillman F, Liu HL et al. Development of policy performance indicators to assess the implementation of protection from exposure to secondhand smoke in China. Tob Control 2013;22(Suppl 2):ii9–15. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wikipedia. List of People's Republic of China administrative divisions by population density 2004. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_People's_Republic_of_China_administrative_divisions_by_population_density (accessed 25 Jun 2014).

- 18.Xiao L, Yang Y, Li Q et al. Population-based survey of secondhand smoke exposure in China. Biomed Environ Sci 2010;23:430–6. 10.1016/S0895-3988(11)60003-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.U.S Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The health consequences of involuntary exposure to tobacco smoke: a report of the Surgeon General. 2006, Atlanta, USA: http://whb.ncpublichealth.com/Manuals/counseling/Secondhand-Smoke.pdf (accessed 25 Jun 2014). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Semple S, Latif N. How long does secondhand smoke remain in household air: analysis of PM2.5 data from smokers’ homes. Nicotine Tob Res 2014;16:1365–70. 10.1093/ntr/ntu089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chu A, Jiang N, Glantz SA. Transnational tobacco industry promotion of the cigarette gifting custom in China. Tob Control 2011;20:e3 10.1136/tc.2010.038349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rich ZC, Hu M, Xiao SY. Gifting and sharing cigarettes in a rural Chinese village: a cross-sectional study. Tob Control 2014;23:496–500. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qin Y, Su J, Xiang QY et al. Effectiveness of a television advertisement campaign on giving cigarettes in a Chinese population. J Epidemiol 2014;24:509–13. 10.2188/jea.JE20130172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang J, Li C, Jia C et al. Smoking, smoking cessation and tobacco control in rural China: a qualitative study in Shandong Province. BMC Public Health 2014;14:916 10.1186/1471-2458-14-916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rich ZC, Hu M, Xiao S. Gifting and sharing cigarettes in a rural Chinese village: a cross-sectional study. Tob Control 2014;23:496–500. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang LL, Thrasher JF, Jiang Y. Impact of the ‘Giving Cigarettes is Giving Harm’ campaign on knowledge and attitudes of Chinese smokers. Tob Control 2015;24(Suppl 4):iv28–34. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sargent JD, Tanski SE, Gibson J. Exposure to movie smoking among US adolescents aged 10 to 14 years: a population estimate. Pediatrics 2007;119:e1167–76. 10.1542/peds.2006-2897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Viswanath K, Ackerson LK, Sorensen G. , et al. Movies and TV influence tobacco use in India: findings from a national survey. PLoS ONE 2010;5:e11365 10.1371/journal.pone.0011365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deng X. Private car ownership in China: how important is the effect of income. Hobart, Australia, 2007. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.508.4336&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed 28 Feb 2016). [Google Scholar]