Abstract

Sunitinib is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor that is used as an anticancer drug in renal cell carcinoma (RCC), pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours (PNETs) and gastrointestinal stromal tumour. Elevated liver enzymes are frequently observed during treatment but acute liver failure is uncommon. We describe a case of fulminant acute liver failure and acute kidney injury during treatment with sunitinib for metastatic RCC.

Background

Sunitinib is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor with antitumour and antiangiogenic activity. The drug targets platelet-derived growth factor, vascular endothelial growth factor, stem cell growth factor (c-KIT) and FLT3 receptor kinases. Sunitinib is a major substrate for hepatic cytochrome CYP3A4 and is excreted into faeces (70–84%) and urine (16%). Common adverse effects are bone marrow depression, fatigue, stomatitis, abdominal discomfort, diarrhoea, skin rash, hand-foot syndrome, hypertension and hypothyroidism. Although elevated liver enzymes and increased serum creatinine frequently occur during treatment with sunitinib, overt hepatic or renal failure is exceedingly rare.

Case presentation

A 79-year-old Caucasian man was admitted to our hospital with acute-onset jaundice during the eight cycle of sunitinib treatment for metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC). His condition had suddenly deteriorated 1 week before admission, with progressive fatigue and malaise.

One year earlier, he had presented with RCC as a coincidental finding during hospital admission for severe diverticulitis. His medical history was otherwise unremarkable except for paroxysmal atrioventricular nodal re-entry tachycardia, for which he used metoprolol 50 mg daily. CT scan revealed a large mass in the right kidney, with three metastatic lesions in the right lung. He underwent an uncomplicated sigmoid resection and nephrectomy. Pathological examination revealed a 9 cm large Fuhrman grade 3 clear cell RCC with extension into the perinephric fat and renal vein; the sigmoid showed inflammation without malignancy. After recovery from surgery, CT scan showed progression of the pulmonary metastases and a new (probably metastatic) liver lesion. Therefore, the patient was started on treatment with sunitinib 50 mg/day (for 4 weeks followed by 2 weeks off treatment). After five cycles, the dose was reduced to 37.5 mg/day because of adverse effects (mainly fatigue, stomatitis and diarrhoea). Further treatment with sunitinib was uneventful (including normal serum liver enzymes and bilirubin at each treatment cycle), and evaluation CT scan performed <10 days before hospital admission for acute-onset malaise and jaundice showed ongoing slight decrease of the pulmonary metastases and disappearance of the liver lesion, and was otherwise unremarkable including normal findings of liver and left kidney.

On admission, we saw an ill-appearing icteric man with a pulse rate of 82 bpm, blood pressure 165/101 mm Hg, oxygen saturation 100% and body temperature 35.5°C. Physical examination was otherwise normal. Laboratory assessment revealed striking abnormalities including acute liver and kidney failure, metabolic acidosis and disseminated intravascular coagulation (table 1).

Table 1.

Laboratory values in the patient

| 28 Days before admission | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Normal ranges | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haemoglobin | 6.2 | 8.0 | 7.0 | (7.5–10.0 mmol/L) | |

| Leucocytes | 3.8 | 7.4 | 9.1 | 9.1 | (4.3–10.0×109/L) |

| Platelets | 145 | 20 | 29 | 25 | (150–400×109/L) |

| Prothrombin time | 28 | 58 | 54 | (8–11 s) | |

| APTT | 34 | 50 | 50 | (20–30 s) | |

| Fibrinogen | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.5 | (2.0–4.5 g/L) | |

| D-Dimer | >3200 | >3200 | |||

| Creatinine | 118 | 266 | 341 | 378 | (55–95 µmol/L) |

| Total bilirubin | 7 | 92 | 157 | 182 | (0–17 µmol/L) |

| Direct bilirubin | 55 | 122 | 144 | (0–17 µmol/L) | |

| ASAT | 18 | 2640 | 4105 | 5964 | (0–37 IU/L) |

| ALAT | 15 | 1844 | 2511 | 3565 | (0–31 IU/L) |

| LDH | 226 | 3386 | 5005 | 6721 | (0–450 IU/L) |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 60 | 78 | 70 | 80 | (25–120 IU/L) |

| γ-GT | 25 | 35 | 47 | (0–35 IU/L) | |

| Lactate | 8.7 | 11.6 | 5.7 | (0.5–2.2 mmol/L) |

ALAT, alanine aminotransferase; APTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; ASAT, aspartate aminotransferase, LDH, lactate dehydrogenase, γ-GT, γ glutamyltransferase.

Ultrasonography showed normal aspect of the abdominal organs with normal liver blood flow. Chest X-ray showed the known metastatic lesions but no infiltrates and no signs of cardiac decompensation. ECG showed a right bundle block without signs of ischaemia. Multiple blood and urine cultures were negative. Acute viral hepatitis was excluded with serological studies for hepatitis A, B, C and E, along with cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus. Our patient had used no medications (including complementary/alternative products) other than metoprolol and sunitinib, which he had discontinued shortly before admission. Nonetheless, the patient's condition deteriorated rapidly, and 4 days after admission, he died in a hepatic coma. Permission for autopsy was not obtained.

Discussion

We present a case of lethal acute liver failure in a patient treated with sunitinib for RCC. During treatment, liver enzymes were monitored frequently and showed no abnormalities throughout the first seven 6-week cycles of treatment. Recent CT scan and actual ultrasonography showed a normal aspect of the liver, with signs of neither venous occlusion nor biliary obstruction. Bacterial infection was very unlikely as the cause of this patient's fulminant liver failure, and acute viral hepatitis was excluded with serological tests. In this case, no explanation for acute liver failure was found other than the use of sunitinib.

Fulminant liver failure associated with treatment using sunitinib is rare and the underlying mechanism is unclear. We suggest that the fulminant liver failure in this case was a type B adverse drug reaction to sunitinib. In contrast to type A, type B reactions are idiosyncratic, unpredictable, usually uncommon, dose independent and unrelated to the drug's known pharmacology.1

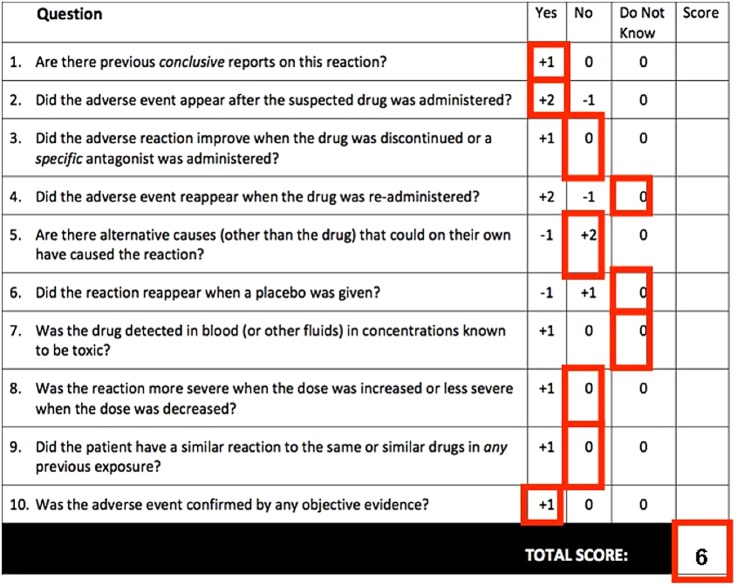

Using the Naranjo adverse effect probability scale, the relationship between sunitinib and hepatotoxicity in this case can be rated as ‘probable’ (figure 1).2 A higher causality association could not be reached due to the fulminant clinical course (ie, no improvement after drug discontinuation and re-challenge not possible). In general, causality assessment can be complicated by lack of validated assessment systems, incomplete information and difficulty interpreting data.3

Figure 1.

Naranjo Adverse Drug Reaction Probability Scale. Scores based on the presented case.

A recent meta-analysis of sunitinib adverse events in metastatic RCC described elevated liver enzymes in 40% of 5658 patients. Grade III/IV elevated liver enzymes occurred in 3% of patients and no fatal hepatotoxicity was reported.4 We found four cases of liver failure in patients treated with sunitinib. Mermershtain et al5 described a patient with acute liver failure during the first cycle of sunitinib for RCC. Another case report mentioned sunitinib-related acute liver failure in a woman with RCC during the fifth treatment cycle, which was reversible after discontinuation of the drug.6 The third case described a patient treated with nine cycles of sunitinib for metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumour, who developed liver failure and died after 4 days.7 Finally, a case of fatal liver failure was reported in a patient with ovarian cancer.8

In conclusion, we report a case of fulminant acute liver failure associated with sunitinib treatment for metastatic RCC. Other reasonable causes of acute hepatic failure were excluded and the cause–effect relationship was rated as probable according to the Naranjo scale. Although frequent monitoring of liver tests continues to be advisable during treatment with sunitinib, it would not have prevented the lethal acute hepatotoxicity in this patient.

Learning points.

Elevated serum liver enzymes occur frequently during sunitib treatment but acute liver failure has rarely been described.

Acute liver failure seems to be dose independent and can occur unexpectedly.

Clinicians should be aware of liver failure as a complication of treatment with sunitinib, even after multiple cycles of treatment.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.de Graaff LC, van Schaik RH, van Gelder T. A clinical approach to pharmacogenetics. Neth J Med 2013;71:145–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drugs reactions. Clinical Clin Pharmacol Ther 1981;30:239–45. 10.1038/clpt.1981.154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meyboom RH, Hekster YA, Egberts AC et al. Causal of casual? The role of causality assessment in pharmacovigilance. Drug Saf 1997;17:374–89. 10.2165/00002018-199717060-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ibrahim EM, Kazkaz GA, Abouelkhair KM et al. Sunitinib adverse events in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Int J Clin Oncol 2013;18:1060–9. 10.1007/s10147-012-0497-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mermershtain W, Lazarev I, Shani-Shrem N et al. Fatal liver failure in a patient treated with sunitinib for renal cell carcinoma. Clin Genitourin Cancer 2013;11:70–2. 10.1016/j.clgc.2012.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mueller EW, Rockey ML, Rashkin MC. Sunitinib-related fulminant hepatic failure: case report and review of the literature. Pharmacotherapy 2008;28:1066–70. 10.1592/phco.28.8.1066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weise AM, Liu CY, Shields AF. Fatal liver failure in a patient on acetaminophen treated with sunitinib malate and levothyroxine. Ann Pharmacother 2009;43:761–6. 10.1345/aph.1L528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taran A, Ignatov A, Smith B et al. Acute hepatic failure following monotherapy with sunitinib for ovarian cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2009;63:971–2. 10.1007/s00280-008-0814-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]