Abstract

An IncN plasmid (p541) from Escherichia coli carried a Citrobacter freundii-derived sequence of 4,252 bp which included an ampC-ampR region and was bound by two directly repeated IS26 elements. ampC encoded a novel cephalosporinase (CMY-13) with activity similar to that of CMY-2. AmpR was likely functional as indicated in induction experiments.

The most widespread plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamases among enterobacteria are those derived from the chromosomal cephalosporinases of Citrobacter freundii. The respective bla genes are carried by various plasmids that may differ in size, self-transfer capability, and antibiotic resistance patterns (15). Recently, we reported on a self-transferable, multiresistant plasmid of 50 kb (p541) from Escherichia coli that encoded an AmpC-type enzyme and the VIM-1 metallo-β-lactamase. The blaVIM-1 gene was located in a class 1 integron (In-e541) (12). The presence of two bla genes encoding potent β-lactamases in the same plasmid prompted us to further characterize p541.

Sequencing of the ampC-carrying region.

Plasmid p541 was transferred by transformation into E. coli DH5α. Replicon typing was performed by Southern blot hybridization using inc-rep probes specific for the major incompatibility groups as previously described (4). Plasmid p541 reacted with only the repN probe and was consequently assigned to the IncN group.

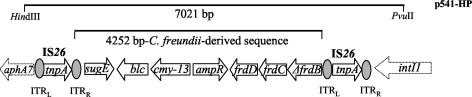

Fragments of p541, produced after partial digestion with HindIII, were ligated into the chloramphenicol-resistant phagemid pBC-SK(+) (Stratagene), and the resulting plasmids were used to transform E. coli DH5α. A recombinant plasmid (p541-H) with a 10,850-bp insert conferred the antibiotic resistance pattern of p541. Based on the sequence of In-e541 (12), the insert was further restricted by PvuII yielding a fragment of 7,021 bp (Fig. 1). A pBC-SK(+) derivative containing the latter fragment (p541-HP) conferred a cephalosporinase phenotype (Table 1).

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of the HindIII-PvuII fragment of plasmid p541 including a C. freundii chromosomal fragment encompassed by IS26 elements. Arrows indicate the direction of transcription. This structure is included in the sequence presented for GenBank accession no. AY339625. ITRR, right ITR; ITRL, left ITR.

TABLE 1.

MICs of β-lactam antibiotics

| Antibiotica | MIC (μg/ml) for E. coli DH5α strains carrying plasmid (β-lactamase[s])

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p541 (CMY-13 + VIM-1) | p541 + pNH5 (CMY-13 + VIM-1) | p541-H (CMY-13 + VIM-1) | p541-HP (CMY-13) | pCMY-13 (CMY-13) | pCMY-2 (CMY-2) | pBC-SK (+) | |

| AMP | ≥1,024 | ≥1,024 | ≥1,024 | ≥1,024 | ≥1,024 | ≥1,024 | 2 |

| TIC | ≥1,024 | ≥1,024 | ≥1,024 | ≥1,024 | ≥1,024 | ≥1,024 | 4 |

| PIP | 512 | 256 | 512 | ≥1,024 | 512 | 512 | 1 |

| TZP | 256 | 128 | 256 | 128 | 128 | 128 | 1 |

| CXM | ≥1,024 | ≥1,024 | ≥1,024 | 512 | ≥1,024 | 512 | 4 |

| FOX | ≥1,024 | 512 | ≥1,024 | 512 | ≥1,024 | ≥1,024 | 4 |

| CTX | 128 | 64 | 256 | 256 | 256 | 256 | 0.06 |

| CRO | 256 | 256 | 256 | 256 | 512 | 512 | ≤0.03 |

| CAZ | 512 | 256 | 512 | 256 | 512 | 256 | 0.12 |

| FEP | 64 | 32 | 64 | 1 | 2 | 1 | ≤0.03 |

| CPO | 64 | 64 | 64 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.06 |

| ATM | 2 | 1 | 8 | 64 | 64 | 32 | 0.06 |

| IPM | 8 | 8 | 8 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.12 |

| MEM | 1 | 1 | 1 | ≤0.03 | 0.06 | 0.06 | ≤0.03 |

AMP, ampicillin; TIC, ticarcillin; PIP, piperacillin; TZP, piperacillin-tazobactam (inhibitor fixed at 4 μg/ml); CXM, cefuroxime; FOX, cefoxitin; CTX, cefotaxime; CRO, ceftriaxone; CAZ, ceftazidime; FEP, cefepime; CPO, cefpirome; ATM, aztreonam; IPM, imipenem; MEM, meropenem.

The sequence of the HindIII-PvuII insert was determined on both strands by a primer walking approach using an ABI PRISM 377 sequencer (Applied Biosystems). It included 4,252 bp that resembled a segment from C. freundii OS60 (GenBank accession no. U21727) containing seven open reading frames (ORFs) (Fig. 1). The first two ORFs encoded putative polypeptides identified as SugE (105 amino acids ⇄, 100% identity) and Blc (177 aa, 98.3% identity) from C. freundii (accession no. U21727). The third ORF (1,143 bp) exhibited >92% homology with the ampC genes of C. freundii and the respective plasmidic cephalosporinases (1). The encoded polypeptide (381 aa) possessed the characteristic motifs of class C β-lactamases (14) and was most similar to the plasmid-mediated CMY-2 (97.4% identity, 98.2% similarity) (3) and the AmpC of C. freundii GN346 (96.5% identity, 98.6% similarity) (accession no. X91840 and D13207, respectively). The calculated isoelectric point (pI) of the putative mature polypeptide (361 aa) was 9.1, in agreement with that determined by isoelectric focusing (pI of 9.0) (12). This novel AmpC variant was designated CMY-13. An ORF of 873 bp, showing an opposite direction of transcription, was identified upstream of blaCMY-13. The putative polypeptide (291 aa) differed by eight residues (97% identity) from the AmpR of C. freundii, the transcriptional regulator of ampC expression (accession no. AY125469) (10). None of these differences was located in the helix-turn-helix region or in other positions important for AmpR function (reviewed in reference 7). The blaCMY-13-ampR intercistronic sequence was identical to that of C. freundii OS60 (accession no. U21727). The remaining three ORFs were identified as frdD, frdC, and a 5′-end-deleted version of frdB (ΔfrdB) constituting part of the fumarate operon that is adjacent to ampC-ampR in C. freundii.

Comparison of CMY-13 with CMY-2.

CMY-13 and CMY-2 were expressed under isogenic conditions. p541-HP and the blaCMY-2-carrying plasmid pMEL (1, 6) were used as templates in PCR with primers P1 (5′-CCGGAATTCTAAGTGTAGATGACAACAGGAAAA-3′) and P2 (5′-CCGGAATTCTTATATCTGCTGCTAAATTTAACCG-3′) containing EcoRI restriction sites (shown in boldface type). Amplicons (1,324 bp) comprising identical parts of the ampC-ampR intercistronic region and the respective blaCMY genes were restricted with EcoRI and ligated into pBC-SK(+). The resulting plasmids, pCMY-13 and pCMY-2, were introduced into E. coli DH5α. Determination of MICs by an agar dilution method (14) showed that CMY-13 and CMY-2 conferred comparable resistance levels to β-lactams, suggesting similar substrate specificities (Table 1).

Inhibition profiles were compared by using tazobactam and Ro 48-1220 as inhibitors and nitrocefin as a reporter substrate as described previously (18). Tazobactam 50% inhibitory concentration values for CMY-13 and CMY-2 were 10.5 and 12 μM, respectively. The 50% inhibitory concentration of Ro 48-1220 was 0.7 μM for both enzymes. Therefore, CMY-13 was considered to be functionally equivalent with the plasmid-mediated, C. freundii-derived AmpC variants represented by CMY-2 (1).

Induction of CMY-13.

The presence of an intact ampC-ampR in p541 implied that CMY-13 production could be inducible. To test this hypothesis, E. coli DH5α cells carrying plasmids p541, p541-H, and p541-HP were used. An E. coli DH5α(p541) transformed with pNH5, a plasmid encoding AmpD from Enterobacter cloacae (8), was also used. Induction was performed by adding imipenem at 1 μg/ml in broth cultures 3 h before harvesting the cells. β-Lactamases were extracted by ultrasonic treatment. The protein concentration was determined by a protein assay kit (Bio-Rad). Hydrolysis of nitrocefin was assessed by spectrophotometry. VIM-1 β-lactamase was blocked by adding EDTA in the respective extracts at a final concentration of 1 mM. Preliminary testing with E. coli DH5α(p541-HP) extracts had indicated that the use of EDTA as described above did not significantly affect cephalosporinase activity.

Induction of E. coli DH5α(p541) caused a 3.5-fold increase in cephalosporinase activity. Lower levels of induction were observed for the clones harboring p541-H and p541-HP (2.0- and 1.7-fold increase, respectively). Also, the transformation of E. coli DH5α(p541) with pNH5 resulted in lower basal amounts of AmpC which were marginally induced by imipenem (1.2-fold increase) (Table 2). AmpD processes muropeptides that act as cofactors for AmpR activation of ampC transcription (7). Increased AmpD activity is expected to reduce AmpC production in the presence of a functional AmpR. These results indicated that ampR in p541 was likely functionally contributing to the regulation of CMY-13 production. Plasmid-mediated, inducible cephalosporinases from Morganella morganii (DHA-1 and DHA-2) and Enterobacter (ACT-1) have been reported previously (2, 5, 16). In this study, the plasmidic location of a functional ampC-ampR system originating from C. freundii is described for the first time.

TABLE 2.

Induction of β-lactamase activity in CMY-13-producing strains

| Strain | Cephalosporinase activity (U/mg of protein)a

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Uninduced | Induced | Inducibility (fold) | |

| E. coli DH5α(p541)b | 1.04 | 3.62 | 3.5 |

| E. coli DH5α(p541, pNH5)b | 0.63 | 0.76 | 1.2 |

| E. coli DH5α(p541-H)b | 2.49 | 5.05 | 2.0 |

| E. coli DH5α(p541-HP) | 3.19 | 5.52 | 1.7 |

| E. coli DH5α | <0.01 | NDc | |

One unit of activity was defined as 1 μmol of substrate hydrolyzed per min. Each value was the mean of three independent measurements not differing more than 10%.

Extracts were pretreated with EDTA as described in the text.

ND, Not determined.

Genetic environment of the C. freundii-derived sequence.

The C. freundii-derived segment was bounded by two directly repeated IS26 elements (Fig. 1). Each 820-bp-long IS26 comprised a transposase gene (tnpA) (705 bp) flanked by characteristic inverted terminal repeats (ITRs) (11, 13). The left-hand IS26 was preceded, up to the HindIII site, by a 755-bp sequence identical to the 5′ end of an aphA7 gene (9). aphA alleles code for aminoglycoside phosphotransferases and occur as parts of various IS26-containing transposons (17, 21). The right-hand IS26 was inserted within frdB, causing its deletion at the 5′ end. The sequence immediately after the right-hand ITR corresponded to the 5′CS of the VIM-1-encoding integron (12). The 5′ conserved sequence (CS) lacked the first 113 bp of the common 5′ end due to the IS26 insertion.

Although the above-described structure resembles a composite transposon, the absence of target site duplications suggests that the two elements might be inserted independently. Notably, a bla-associated IS26 located in the 5′ CS of a class 1 integron as in p541 has been described in three additional multiresistant plasmids: pSEM (an IncL/M plasmid from Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium encoding SHV-5; GenBank accession no. AJ245670) (19), p1658/97 (an IncF plasmid from E. coli also encoding SHV-5; accession no. AF550679), and pAK33 (an E. coli plasmid encoding IBC-1 β-lactamase; accession no. AY260546) (20). No marked target selectivity has been described for IS26 (11). It can be hypothesized that the IS26-Δ5′ CS sequence was part of a common mobile structure which spread among distinct plasmids and evolved through the acquisition of gene cassettes and IS26-mediated transposition or recombination events.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The described nucleotide sequence has been deposited in GenBank under accession no. AY339625.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barlow, M., and B. G. Hall. 2002. Origin and evolution of the AmpC β-lactamases of Citrobacter freundii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1190-1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnaud, G., G. Arlet, C. Verdet, O. Gaillot, P. H. Lagrange, and A. Philippon. 1998. Salmonella enteritidis: AmpC plasmid-mediated inducible β-lactamase (DHA-1) with an ampR gene from Morganella morganii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2352-2358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bauernfeind, A., I. Stemplinger, R. Jungwirth, and H. Giamarellou. 1996. Characterization of the plasmidic β-lactamase CMY-2, which is responsible for cephamycin resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:221-224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Couturier, M., F. Bex, P. L. Bergquist, and W. K. Maas. 1988. Identification and classification of bacterial plasmids. Microbiol. Rev. 52:375-395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fortineau, N., L. Poirel, and P. Nordmann. 2001. Plasmid-mediated and inducible cephalosporinase DHA-2 from Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 47:207-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gazouli, M., L. S. Tzouvelekis, E. Prinarakis, V. Miriagou, and E. Tzelepi. 1996. Transferable cefoxitin resistance in enterobacteria from Greek hospitals and characterization of a plasmid-mediated group 1 β-lactamase (LAT-2). Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:1736-1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanson, N. D., and C. C. Sanders. 1999. Regulation of inducible AmpC beta-lactamase expression among Enterobacteriaceae. Curr. Pharm. Des. 5:881-894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Honore, N., M.-H. Nicolas, and S. T. Cole. 1989. Regulation of enterobacterial cephalosporinase production: the role of a membrane-bound sensory transducer. Mol. Microbiol. 3:1121-1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee., K. Y., J. D. Hopkins, and M. Syvanen. 1991. Evolved neomycin phosphotransferase from an isolate of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Mol. Microbiol. 5:2039-2046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lindquist, S., F. Lindberg, and S. Normark. 1989. Binding of the Citrobacter freundii AmpR regulator to a single DNA site provides both autoregulation and activation of the inducible β-lactamase gene. J. Bacteriol. 171:3746-3753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mahillon, J., and M. Chandler. 1998. Insertion sequences. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:725-774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miriagou, V., E. Tzelepi, D. Gianneli, and L. S. Tzouvelekis. 2003. Escherichia coli with a self-transferable, multiresistant plasmid coding for the metallo-β-lactamase VIM-1. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:395-397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mollet, B., S. Iida, J. Sepherd, and W. Arber. 1983. Nucleotide sequence of IS26, a prokaryotic mobile genetic element. Nucleic Acids Res. 11:6319-6330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2000. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically, 5th ed. Approved standard M7-A5. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 15.Philippon, A., G. Arlet, and G. A. Jacoby. 2002. Plasmid-determined AmpC-type β-lactamases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reisbig, M. D., and N. D. Hanson. 2002. The ACT-1 plasmid-encoded AmpC β-lactamase is inducible: detection in a complex β-lactamase background. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 49:557-560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tauch, A., S. Krieft, J. Kalinowski, and A. Puhler. 2000. The 51,409-bp R-plasmid pTP10 from the multiresistant clinical isolate Corynebacterium striatum M82B is composed of DNA segments initially identified in soil bacteria and in plant, animal, and human pathogens. Mol. Gen. Genet. 263:1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tzouvelekis, L. S., M. Gazouli, E. E. Prinarakis, E. Tzelepi, and N. J. Legakis. 1997. Comparative evaluation of the inhibitory activities of the novel penicillanic acid sulfone Ro 48-1220 against β-lactamases that belong to groups 1, 2b, and 2be. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:475-477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Villa, L., C. Pezzela, F. Tosini, P. Visca, A. Petrucca, and A. Carattoli. 2000. Multiple-antibiotic resistance mediated by structurally related IncL/M plasmids carrying an extended-spectrum β-lactamase gene and a class 1 integron. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:2911-2914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vourli, S., L. S. Tzouvelekis, E. Tzelepi, E. Lebessi, N. J. Legakis, and V. Miriagou. 2003. Characterization of In111, a class 1 integron that carries the extended-spectrum β-lactamase gene blaIBC-1. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 225:149-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wrighton, C. J., and P. Strike. 1987. A pathway for the evolution of the plasmid NTP16 involving the novel kanamycin resistance transposon Tn4352. Plasmid 17:37-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]