Abstract

Osteoporosis is a global health problem that leads to an increased incidence of fragility fracture. Recent dietary patterns of Western populations include higher than recommended intakes of n–6 (ω-6) polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) relative to n–3 (ω-3) PUFAs that may result in a chronic state of sterile whole body inflammation. Findings from human bone cell culture experiments have revealed both benefits and detriments to bone-related outcomes depending on the quantity and source of PUFAs. Findings from observational and randomized controlled trials suggest that higher fatty fish intake is strongly linked with reduced risk of fragility fracture. Moreover, human studies largely support a greater intake of total PUFAs, total n–6 (ω-6) fatty acid, and total n–3 (ω-3) fatty acid for higher bone mineral density and reduced risk of fragility fracture. Less consistent evidence has been observed when investigating the role of long chain n–3 (ω-3) PUFAs or the ratio of n–6 (ω-6) PUFAs to n–3 (ω-3) PUFAs. Aspects to consider when interpreting the current literature involve participant characteristics, study duration, diet assessment tools, and the primary outcome measure.

Keywords: bone health, fatty acids, osteoporosis, women's health, α-linolenic acid, arachidonic acid, eicosapentaenoic acid, docosahexaenoic acid, bone mineral density, fracture

Introduction

Osteoporosis.

Fragility fractures resulting from osteoporosis—characterized by a low skeletal mass and poor bone microarchitecture—often result in substantial morbidity and reduced overall quality of life. Women and men alike begin to lose bone mass in adulthood, whereas women tend to experience a loss of bone mineral and compromised bone structure at a greater rate as they approach menopause due to the loss of endogenous estrogen production. Together, the loss of bone mineral and deterioration of bone structure results in a higher risk for fragility fracture. At least 1 in 3 women and 1 in 5 men will suffer a fragility fracture during their lifetime. In the United States, >2 million osteoporosis-related fragility fractures occurred in 2005. By 2025, it is projected that the number of fractures and associated costs, including rehabilitation programs and long-term care, will rise by 50% (1). In addition to the economic burden, incident fractures can markedly compromise an individual’s quality of life. Clinically relevant reductions to health-related quality of life scores persist up to a year after fracture, and these reductions are more prolonged after hip or vertebral fracture (2–6). A fragility fracture will alter all aspects of daily life, including such simple tasks as reaching, twisting, and bending.

Worldwide, the incidence of fragility fracture varies substantially by geographical region. In 2000, there were an estimated 9 million new osteoporotic fractures worldwide, with the Americas and Europe alone accounting for 51% of the worldwide burden (7). Age-adjusted incidence rates of hip fracture among women from rural Asian countries reached only 50% of Caucasian rates, whereas rates in urbanized Asian countries were similar to white American women (8). The regional variation may be attributed to differences in lifestyle, including dietary patterns that may involve different intakes of macronutrients, micronutrients, and bioactives–all of which can influence bone health. Of specific interest is the association of PUFA intake with bone health. Most (9–14) but not all (15–17) observational studies suggest that diets high in fish and seafood, rich sources of the long chain n–3 PUFAs, are associated with benefits to bone health in postmenopausal women.

Metabolism, recommended intake, and food sources of PUFAs.

The n–6 and n–3 series of PUFAs are of particular interest because they contribute to the structure and the function of the phospholipid bilayers in cellular membranes and function as the precursors of lipid-mediated signaling molecules. These different functions may influence bone cell metabolism. Currently, there are DRIs for the 2 essential fatty acids: linoleic acid (LA2; 18:2n–6) and α-linolenic acid (ALA; 18:3n–3). The adequate intake for LA and ALA for women and men age 50–70 y is 11 g/d and 14 g/d and 1.1 and 1.6 g/d, respectively (18). LA and ALA compete for the same pool of elongase and desaturase enzymes for their conversion to the longer chain and less saturated fatty acids: arachidonic acid (AA; 20:4n–6), EPA (20:5n–3), and DHA (22:6n–3). This conversion is relatively inefficient, with 21% and 9% of ALA converted to EPA and DHA, respectively (19).

Although there is no DRI for the long chain PUFAs, it is suggested that we consume at least 2 servings of fish/wk, which provides ~0.3–0.45 g EPA and DHA/d (18). Moreover, consumption of a 10:1 ratio of n–6 to n–3 fatty acids for women and a 8.75:1 ratio for men is recommended as part of a healthy lifestyle (18). Of the n–6 fatty acids, LA is present in many edible plant oils, including corn, soybean, and canola oil and is the predominant PUFA consumed in Western diets (20), whereas meat, poultry, and dairy are rich sources of AA. Omega-3 fatty acids, primarily ALA, contribute ~10% of the total PUFA intake (this total includes both n–3 and n–6 PUFA intake) (20) and are found in high concentrations in flaxseed, walnuts, soy, and n–3 fortified food products.

It has been estimated that the present PUFA ratio in the average Western diet ranges from 15 through 17 to 1 (21), whereas Canadian data indicate the dietary intakes are in the range of 7 or 8 to 1 (22). In Canada, approximately half of all edible oil consumed is canola oil, rich in MUFAs with a PUFA ratio of ∼2:1 (23). The preferential edible oil in the United States is soybean oil (24), which is made up of over 50% LA, resulting in a PUFA ratio of ~7:1 (23). Diet patterns and supplement use of a population are influenced by public health messages, food technology innovations, availability, geographical region, and economic burden. For instance, recommendations for PUFA intake vary by country and its governing health organization. Current n–3 PUFA dietary intake recommendations for adults as set by selected global governing bodies are summarized in Table 1. Most of these current recommendations are based on established benefits to cardiovascular health, i.e., lowering total blood and LDL-cholesterol concentrations (34). Benefits to bone health have been observed at or above the upper threshold of the current DRI for n–3 PUFAs as ALA in postmenopausal women. This suggests that the n–3 PUFA (ALA) recommendations set out for general health and heart health similarly support bone health in the female adult population. Less consistent findings exist when interpreting the implications to bone health from various ranges of EPA and DHA intakes.

TABLE 1.

Current n–3 PUFA recommendations for general health in the adult population as set by different organizations throughout the world1

| Organization (reference) | n–3 PUFA recommendations |

| International | |

| FAO/WHO (25) | 0.5–2% Energy from n–3 PUFAs |

| 0.25–2 g EPA + DHA/d | |

| Canada and/or United States | |

| Institute of Medicine (18) | 1.1–1.6 g total n−3 PUFAs/d (10% from EPA + DHA) |

| Dietitians of Canada (26) | 1.1–1.6 g total n−3 PUFAs/d |

| 500 mg EPA + DHA/d | |

| Health Canada (27) | 2 Servings of fish/wk |

| Suggested sources: char, herring, mackerel, salmon, sardines, trout | |

| American Heart Association (28) | At least 2 servings of fish (fatty)/wk |

| Include oils and foods rich in ALA | |

| American Diabetes Association (29) | ≥2 Servings of fish/wk |

| Europe | |

| French Agency of Food and Health Safety (30) | 0.8% Energy from n–3 PUFAs 0.05% Energy from DHA 500 mg EPA + DHA/d |

| Nordic Nutrition Recommendations (31) | >1% Energy from n–3 PUFAs |

| Asia-Pacific | |

| National Heart Foundation of Australia (32) | 2 g ALA/d 500 mg EPA + DHA/d |

| National Institute of Health and Nutrition, Japan (33) | 1.8–2.2 g total n−3 PUFAs/d (>1 g EPA + DHA/d) |

ALA, α-linolenic acid.

Current Methodologies for Measuring Bone Health in Human Studies

In a clinical setting, the diagnosis of osteoporosis is largely based on bone mineral density (BMD) as measured by DXA. Although BMD is an important factor, most fragility fractures occur in individuals with T-scores for BMD that are above the defining osteoporotic threshold (35–37). To better predict an individuals risk of fragility fracture, the fracture risk assessment tool FRAX was developed by the WHO to estimate an individuals 10-y major osteoporotic and hip fracture probability (38). In Canada, the CAROC (Canadian Association of Radiologists and Osteoporosis Canada) system uses a similar criteria to categorize 10-y major osteoporotic fracture risk as low (<10%), moderate (10–20%), or high (>20%) based on individual patient risk factors combined with their BMD score (39). Although these tools are ideal for individual risk assessment, current studies investigating dietary fat and bone health are limited to reports of fracture incidence, BMD, and biochemical markers of bone metabolism.

Fragility fracture incidence.

Ultimately, the incidence of fragility fracture is the most clinically relevant assessment tool when attempting to quantify the effect of a dietary pattern in a population. This method requires a very large sample size and a long duration of study (>3 y), which may not be ideal for some experimental designs. Studies in this review reporting fragility fracture as a main outcome have had follow-up periods 5.2 to 24 y in length.

BMD by DXA.

DXA is currently the gold standard in clinical practice for the diagnosis of osteoporosis by the WHO guidelines (40). A DXA scan quantifies the amount of bone mineral, termed bone mineral content (in g), within a defined area (e.g., hip, spine, wrist) and from these values BMD (in g/cm2) is derived. Because BMD is dependent on bone size, comparison of raw values across individuals or across studies must be interpreted with caution. DXA is advantageous in clinical practice because of its low radiation dose, fast and simple operation, and relatively low cost. Although DXA measurements are limited to quantitative outcomes that, as discussed earlier, are arguably not a reliable predictor of fracture risk on their own, assessment of bone structure is now sometimes assessed by using high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography (HR-pQCT). Low-trauma fragility fractures in postmenopausal women have been associated with negative changes to trabecular and cortical microarchitecture as assessed by HR-pQCT, but most of these associations were independent of BMD as measured by DXA (41). Although HR-pQCT results are powerful in their precision, they require specialized equipment and trained personnel and are currently limited to analysis of the axial skeleton. This newer measurement of bone structure was not used in the studies discussed in this review.

Bone-derived biochemical markers.

Derived from the cellular and the noncellular compartments of bone and measured in blood or urine, biochemical markers are considered a noninvasive measure of bone cell activity and overall bone turnover. These biochemical markers are classified as either bone formation or bone resorption markers. Generally, bone formation markers are products of the osteoblast or from collagen synthesis, whereas bone resorption markers are osteoclast-specific proteins or are produced as a result of collagen breakdown (42). These markers can be measured more frequently (in weeks) than BMD measurements (in months-years) and thus are often reported as main outcomes in randomized controlled trials (RCTs). A limitation to these markers can be their high intervariability.

Eicosanoid Production and Function in Human Cell Culture Models

PUFA-derived signaling molecules.

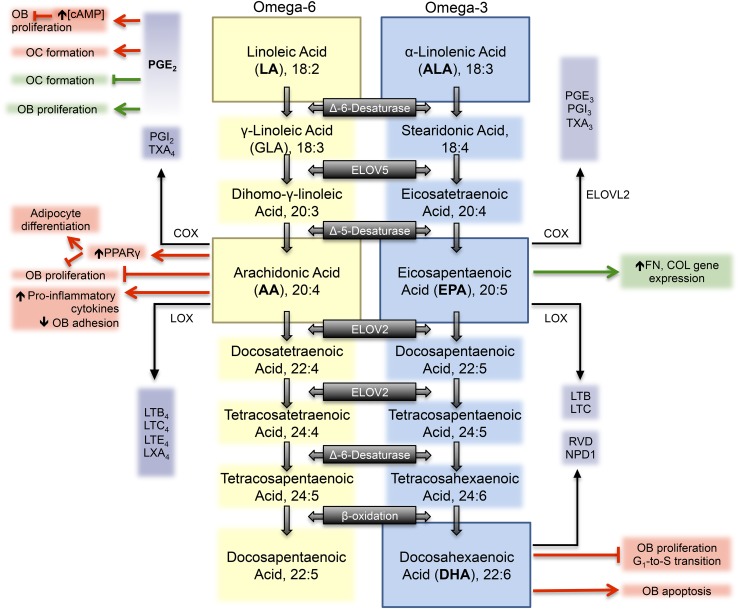

The long chain PUFAs—AA, EPA, and DHA—are substrates of the enzymes cyclooxygenase (constitutive cyclooxygenase-1 and inducible cyclooxygenase-2) and lipoxygenase for the production of small signaling molecules that can be either pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory in nature (Figure 1). Catalyzed by the cyclooxygenase and lipoxygenase enzymes, EPA and DHA are substrates for the production of 3-series prostaglandins, thromboxanes, and resolvins, generally considered to have anti-inflammatory properties. AA is the major n–6 PUFA precursor of the pro-inflammatory eicosanoid pathway, which gives rise to the 2- and 4-series of prostaglandins, thromboxanes, and leukotrienes. Dihomo-gamma-linolenic acid, (20:3n–6), AA, and EPA are the main substrates of the cyclooxygenase enzymes and generate the 1-, 2- and 4-, and 3-series of prostaglandins, respectively (Figure 1). These substrates are in direct competition for this key conversion enzyme and its isozymes, but cyclooxygenase exhibits the greatest specificity for AA such that PGE2 is preferentially produced (43).

FIGURE 1.

Metabolism of the essential n–6 (LA) and n–3 (ALA) PUFAs. AA and EPA or DHA are substrates for the production of eicosanoids generally considered to be pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory in nature, respectively, and have a variety of effects in human bone cell culture. Omega-6 PUFAs, omega-3 PUFAs, and their downstream eicosanoids are depicted by yellow, blue, and purple colored boxes, respectively. Outcomes generally considered to be supportive of bone health are highlighted in green boxes. Outcomes generally considered to be detrimental to bone health are highlighted in red boxes. AA, arachidonic acid; ALA, α-linolenic acid; COL, type 1 collagen; COX, cyclooxygenase; ELOV, elongase; FN, fibronectin; GLA, γ-linoleic acid; LA, linoleic acid; LOX, lipooxygenase; LTB, leukotriene-B; LTC, leukotriene-C; LTE, leukotriene-E; LXA, lipoxin-A; NPD1, neuroprotectin D1; OB, osteoblast; OC, osteoclast; PGI, prostacyclin I; RVD, D-series resolvin; TXA, thromboxane-A.

PGE2 production is stimulated in response to treatment with AA, and both cyclooxygenase-1 and cyclooxygenase-2 isozymes are involved in this AA-stimulated PGE2 production (44). In vitro, PGE2 exhibits biphasic properties and at low concentrations (10−11 to 10−9 M) is a potent stimulator of bone formation and of proliferation in primary human bone cultures, whereas at higher concentrations (10−7 M) it inhibits proliferation via cAMP production and signaling (45, 46). Although it is generally well accepted that PGE2 enhances the differentiation of murine osteoclast precursors into mature osteoclasts (47–49), the effects of PGE2 on human osteoclast formation remains controversial. With the use of the same low dose of PGE2 (10−8 M), 2 independent studies concluded that incubation with PGE2 induces osteoclast formation and bone resorption in primary human bone marrow cultures in vitro (50, 51), whereas a third strongly stated that PGE2 inhibits osteoclast formation from human CD14+ hemopoetic cells (47). The discrepancy in these studies may lie in the primary cell types isolated as well as the culture procedure followed to induce osteoclastogenesis in vitro.

PGE2 is also highly responsive to mechanical loading and is rapidly released from mechanically stimulated osteocytes in order to initiate the Wnt/β-catenin anabolic pathway (52, 53). In an in vitro setting, strain applied to human osteoblast–like cells caused an increase in PGE2 and osteoprotegerin release, and a decrease in macrophage-colony stimulating factor (M-CSF) production (54). Sclerostin, a potent inhibitor of bone formation, has been shown to downregulate in response to mechanical strain, and this process is mediated by PGE2 signaling (55).

As a consequence of greater specificity of cyclooxygenase for n–6 PUFAs, an overproduction of n–6 fatty acid–derived eicosanoids can occur when AA concentrations are in excess. Current dietary ratios consumed in Western populations (21, 22) provide an excess of n–6 PUFAs, which may lead to a chronic state of sterile inflammation within the body that has been linked to chronic disease states such as cancer, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease (56–61).

Actions of fatty acids on human osteoblast–like cell lines.

In vitro experiments involving supplementation of cell culture media with individual fatty acids have been conducted to understand how free fatty acids modulate the activity and function of specific bone cell types. Studies involving SFAs, primarily palmitic acid (16:0) and stearic acid (18:0), suggest that they are harmful to human osteoblast–like cells in culture by inducing apoptosis through Caspase 3/7 signaling and by reducing markers of osteoblast activity (62–65). Also, incubating human SaOS-2 and MG-63 cells in rabbit serum, which consists of a concentrated mixture of palmitic, oleic, and linoleic acids, stimulated adipocyte-differentiation through activation of PPARs to a greater extent (35-fold higher) than incubation in FBS alone (66). Together, these findings suggest a detrimental effect of SFA on the human osteoblast in cell culture.

Very few studies, to our knowledge, have investigated the effect of the essential n–6 fatty acid, LA, in human-derived bone cell culture. Treatment of human mesenchymal stem cell–derived osteoblasts with LA had no effect on markers of apoptosis or function (64). More data exist regarding the effect of AA in the synthesis and signaling of PGE2. Proliferation of primary human osteoblasts and osteoblast-like cells has been shown to decrease when exposed to AA in concentrations ranging from 3 to 20 μmol/L (67, 68), with no indication of structural damage to the cells or to apoptosis. This inhibition in cell proliferation may be due to an increased mRNA and protein expression of PPARγ, a known regulator of mesenchymal stem cell differentiation into the adipocyte-lineage (69, 70) as observed following a 3-wk incubation with AA (30 μmol/L) (71). Exposure to AA has also been shown to increase the mRNA expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1α, IL-1β, TNF-α, M-CSF, and IL-16 in a time- and dose-dependent manner, eliciting maximal effects following a 3-h incubation with 75 μmol AA/L (72, 73). AA may also modulate osteoblast function through cell adhesion. The ability of the osteoblast to adhere has a direct effect on the cells response to surrounding stimuli and to its metabolism. Cellular adhesion was found to temporarily decrease in the presence of 75 μmol AA/L with no changes to the pattern of extracellular matrix mRNA expression (74).

The effect of n–3 PUFAs on human bone cells, similar to that of the n–6 PUFAs, is complex. In the osteoblast-like cell line, although treatment with EPA alone (75 μmol/L) caused no change to inflammatory cytokine mRNA expression, simultaneous treatment with AA caused a significant inhibitory effect on the AA-induced cytokine expression (72). Positive effects of 75 μmol EPA/L were also observed in MG-63 cells, whereby treatment caused no changes to cellular adhesion compared with control, but increases in the gene expression of some extracellular matrix proteins were found (74).

DHA caused a dose-dependent (10–50 μmol/L) decrease in osteoblast proliferation as measured by thymidine incorporation (68). However, this decrease in proliferation cannot be fully attributed to PPARγ-regulated differentiation, because DHA had no effect on PPARγ protein concentrations in primary human osteoblast cells (71). In support of this finding, in MG-63 human osteoblast–like cells, lower amounts of DHA (1–6 μmol/L) caused a dose-dependent inhibition of cell proliferation and induced apoptosis to a greater degree than control or treatment with AA or PGE2 (67). These inhibitory effects of DHA may be attributed to its inhibition of the G1-to-S-phase transition in the cell cycle (68). Other mechanisms of inhibition may be through the role of PUFAs as second messengers, which may interrupt downstream signaling involved in proliferation. Long chain PUFA incorporation into the cell membrane will alter the fluidity and permeability of the membrane itself, and the sensitivity of the membrane-associated proteins, which may also decrease the proliferative process.

Overall, treatment with SFA, AA, or DHA results in detrimental outcomes to human osteoblast cell cultures, including decreased proliferation and more apoptotic events. No changes to the expression pattern of osteoblast specific proteins or to cytokines have been observed in the limited studies treating cells with LA. Generally, the expression of inflammatory cytokines is reduced with ALA and/or EPA treatment.

Findings from Observational Studies

Multiple large observational studies have investigated the associations between dietary patterns and bone-related outcomes. Specifically, individual fatty acid intake, ratio of fatty acid intake, or fish consumption has been quantified and compared to either the risk of fragility fracture, BMD, or a combination of these outcomes to identify associations. Although the majority of studies show a positive association, there are many aspects of the studies under review to consider when interpreting findings (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Aspects to consider when reviewing observational studies assessing the effect of PUFA intake on bone health1

| Participant baseline characteristics | Age, sex, ethnicity, BMI, physical activity, years since menopause, hormone therapy use, previous fracture incidence, protein intake, vitamin D intake, and calcium intake are all variables that modulate bone health |

| Dietary patterns | FFQ: captures habitual dietary patterns; generally is less detailed than other methods (75); is more likely to overestimate intake; is less expensive |

| 24-h Recall, food diaries: capture a snapshot of dietary patterns; time consuming | |

| Dietary patterns and supplement use: may change over time with changing public health recommendations | |

| Accessibility to fresh food items: changes with season, geographical region, and economic burden | |

| Follow-up time: wide range of average follow-up times among studies (3–24 y) | |

| Ability of the diet assessment tool to accurately estimate intake of FA chain length and saturation index, i.e., n–3 PUFAs from plant or animal sources | |

| Sensitivity of the diet assessment tool to differentiate between FA sources, i.e., dark fish vs. fried fish vs. canned fish, etc. | |

| Range of intake: variation of dietary intake among the sample population must be wide enough to establish distinct subgroups of intake | |

| Primary outcome measure | Fracture risk: clinically relevant measure; results may be masked by a short follow-up period, error in self-reporting fractures, or changes to fall incidence with dietary patterns |

| BMD by DXA: measures skeletal site–specific effects; changes may be observed without concomitant changes in fracture incidence | |

| HR-pQCT: nondestructive imaging techniques that allow for the 3-dimensional quantification of bone structure and strength may be a more sensitive measure of bone health; not used in the studies relevant to this review |

BMD, bone mineral density; HR-pQCT, high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography.

Fatty acid intake and risk of hip fracture.

Examination of the association between dietary intake of PUFAs and the risk of hip fracture has resulted in conflicting findings in several large observational studies. Analysis of the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS), in which postmenopausal women were followed for 24 y, showed a significant age-adjusted reduction in risk of hip fracture (RR 0.78, 95% CI; 0.64, 0.94) among women in the highest quintile of total n–3 PUFA intake (1.6 g/d) compared with those in the lowest quintile (0.9 g/d) (13). EPA and DHA intake also showed a significant age-adjusted, hip fracture risk reduction (RR 0.88, 95% CI; 0.72, 1.07) between women in the highest (0.37 g/d) and the lowest (0.07 g/d) quintile of intake. After further multivariate-adjustment, all associations were lost. No associations with ALA, the major constituent of total n–3 PUFAs in the diet, were observed with hip fracture risk. Inverse associations between LA intake and hip fracture risk were found among women in the highest (12.1 g/d) compared with the lowest (6.8 g/d) quintile of intake. The multivariate-adjusted relative risk was lower (RR 0.81, 95% CI; 0.67, 0.98) in the highest than in the lowest quintile of LA intake among women. Although LA has long been considered a precursor of pro-inflammatory eicosanoids, which have a negative impact on bone metabolism, these results suggest a benefit to consuming >6.8 g/d, and possibly up to 12.1 g/d. Although a significant reduction in risk was observed between the highest and lowest quintile of intake, a modest reduction in risk was evident in the second quintile, with little to no additional benefit with higher intake of LA (13). These findings support a minimum requirement of >6.8 g LA intake/d to provide a benefit to bone health in women and that intake as high as 12.1 g/d does not cause a detriment. These data support the previously discussed cell data showing that PGE2 may have a concentration-dependent influence on bone formation and bone resorption.

In another large cohort of 137,486 postmenopausal American women enrolled in the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI), a higher intake of total PUFAs, supplied primarily from n–6 fatty acids, was associated with a lower total fracture risk after an average follow-up of 7.8 y (76). Age-adjusted total fracture rates decreased with increasing n–3 PUFA intake when stratified by quartiles, and the lowest hip fracture rates were associated with the highest n–3 intake (2.1 g/d). ALA was the main n–3 PUFA in the diet, with women consuming an average of 1.27 g/d and an average EPA + DHA intake of 0.13 g/d. A significant reduction in total fracture risk was observed in women in the highest quartile of ALA consumption when adjusted for age and ethnicity but not with further adjustment. Although women with the highest intake of EPA + DHA (0.17 g/d) experienced a lower risk of hip fracture in a model adjusted for age and ethnicity, an increased risk of total fractures was reported after multivariate adjustment. The multivariate model adjusted for factors including family history of fracture, medication use, previous fracture incidence, vitamin intake, exercise, parity, and smoking status. To clearly elucidate the degree to which each factor contributes to the changing risk of fracture, backward selection statistical analysis could be done retrospectively. Because the intake of EPA + DHA was very low in this population (0.08–0.17 g/d), it is not possible to examine associations at higher PUFA intakes. Also, when women were categorized by total n–3 PUFA intake at baseline, although those in the highest quartile of intake experienced fewer falls in the previous 12 mo than others, these women had greater BMI and participated in less physical activity than those in the first and second quartile. Women in the highest quartile also consumed less protein than those in the first and third quartile. It is well established that high BMI, physical activity, and protein intake provide benefits to bone health by increasing BMD and reducing fracture risk (77–79). Similar to associations observed with ALA intake, high consumption of n–6 PUFAs (6.94 g/d), predominately in the form of LA, was also associated with a decrease in total fracture risk compared with that of women in the lowest quartile (0.61 g/d) of n–6 PUFA consumption (76). Together, these data suggest a higher intake of ALA and total n–6 PUFAs is associated with a lower risk of fragility fracture.

Ratio of fatty acid intake and risk of hip fracture.

As discussed earlier, LA and ALA and their longer chain derivatives share common enzymes; however, the metabolically active products have roles as pro- and anti-inflammatory mediators in the body (Figure 1) (57, 80). These 2 contrasting groups of pro- and anti-inflammatory mediators suggest the importance of the PUFA ratio in the diet. The NHS and WHI considered the PUFA ratio in their analyses. Results from these 2 large cohorts show no significant associations with the dietary ratio of total n–6 to n–3 fatty acids and hip fracture risk. In the NHS, the ratio varied from <6.7 in the lowest quintile to >8.9 in the highest (13). This range may have been too narrow to detect any differences in fragility fracture risk in the population. From the WHI, dietary PUFA ratios spanned 0.49–39.01 with a mean ratio of 7.6 (76). But, a 7% reduction in relative risk of total fractures was discovered in this population of postmenopausal women when the total n–6:n–3 PUFA ratio was >6.4 compared with those with a PUFA intake ratio <6.4. This data provides support for the importance of attaining a minimum daily dietary intake of n–6 PUFAs for the proper maintenance of bone health.

Fish consumption and risk of fracture.

Although intake of individual fatty acids and their association with fracture provide us with specific information regarding the benefits of PUFA consumption on fracture risk, it is important to also consider the association with a food source, such as fish. Fatty fish are rich sources of EPA and DHA, although the amount of each vary widely among fish species. Moreover, dark fish (e.g., swordfish, salmon, mackerel, sardines) are also a good source of vitamin D, critical for bone health. In the 18-y follow-up study of the NHS, consisting of over 72,000 postmenopausal women, consumption of a 85–142 g serving of dark fish >1 time/wk resulted in a 33% lower risk of hip fracture than did consumption of dark fish <1 time/mo (9). Separate analysis of the same population of white American women, followed for 24 y rather than 18 y, showed a significant reduction in age-adjusted hip fracture risk among women who consumed >5 servings/wk of fish compared with those who consumed <1 serving/mo (13). In a large study of adult men and women enrolled in the Oxford cohort of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC), total fracture rates for self-identified fish eaters were similar to meat eaters and vegetarians (81). The different self-reported dietary groups consumed similar amounts of calcium, which may at least partially help to explain the similarity in fracture rates observed over the 5.2-y follow-up period, although protein and vitamin D intake was considerably higher in meat-eaters than in the other dietary groups (82).

Fatty acid intake and BMD.

In a recent 3-y prospective study of postmenopausal women from Finland (83), a significant increase in multivariate-adjusted lumbar spine BMD was observed with increasing intake of certain PUFA types. From the lowest to highest quartiles of intake of total PUFAs, LA, ALA, and total n–6 fatty acid, an increase in BMD of the lumbar spine was observed. A similar significant pattern was observed for total body BMD with increasing LA, total n–6 fatty acid, and total n–3 fatty acid intake. No associations were found for EPA + DHA, or AA intake with lumbar spine or total body BMD. Similarly, in a pooled population of older men and women, above average total n–3 fatty acid intake (>1.27 g/d) was associated with greater femur neck BMD and total femur BMD (84). Authors of the study further identified men in the highest quartile of EPA + DHA, EPA, or DHA intake lost significantly less femur neck BMD than those in the lowest quartile of intake over a 4-y follow-up (12). No associations were observed with ALA intake, suggesting that it is the long chain n–3 PUFAs that are most strongly associated with bone health in this study. In another cross-sectional study of postmenopausal Japanese women, total n–3 fatty acid intake, where the primary source of n–3 PUFAs was from fish, was positively associated with lumbar spine BMD (85). The average daily n–3 PUFA intake was 2.7 g/d, and these findings were independent of bone resorption and formation markers. Results from a secondary analysis of 266 postmenopausal women enrolled in the Bone Estrogen Strength Training (BEST) Study found negative associations with total body and lumbar spine BMD and total fat, PUFAs, n–6 fatty acid, LA, n–3 fatty acid, and ALA in women receiving hormone replacement therapy (HRT) after multiple regression analysis (86). These associations were not seen in women who did not receive HRT. In women not receiving HRT, the only observed positive association was between AA intake (0.11 g/d) and trochanter BMD. In both HRT users and nonusers, a significant negative association in total body BMD was observed with increasing tertiles of n–6 and n–3 fatty acid intake (86).

Most recently, the association of n–3 PUFA supplement use and BMD was examined in a diverse data set of the US population with the use of the NHANES (2005–08) data set (87). In a population of 2125 men and women over 60, use of n–3 fatty acid supplements showed a positive association with lumbar spine BMD, but not femur neck or total femur BMD measured with the use of DXA. Within this study, only 15% of individuals reported using n–3 fatty acid supplements (87).

Ratio of fatty acid intake and BMD.

In a fully adjusted model of analysis of postmenopausal women not using HRT enrolled in the Rancho-Bernardo study, the ratio of total n–6 to total n–3 PUFAs was negatively associated with total hip and lumbar spine BMD (88). The population of mid-upperclass, white residents of Southern California who participated in this study consumed a relatively low ratio of total n–6 to n–3 fatty acids (mean ± SD: 7.9 ± 2.2) made up of 10.2 and 1.3 g n−6 and n−3 PUFAs/d, respectively. Men consumed a mean ± SD total PUFA ratio of 8.4 ± 2.5, which was significantly greater than the average intake by women, and no associations were observed with BMD at either hip or spine. Similarly, in a population of 554 postmenopausal women with generally low LA intake (5.9 g/d), there was an interaction of HRT on the inverse relation between the ratio of LA to ALA and BMD of lumbar spine and total body (83). In this study, relations between PUFA intakes and BMD were analyzed by using the entire population as well as within HRT users and nonusers, separately. Exogenous hormone replacement has a profound effect on the skeleton following menopause and may mask any effects of dietary patterns. HRT users in this study used hormone replacement drugs for an average of 11 y and, as a result, their adjusted mean BMD at the lumbar spine and hip was almost always greater than nonusers in the same dietary quartile of PUFA intake (83). Similarly, HRT users in the BEST Study had greater BMD at all skeletal sites measured, but regardless of the use of HRT, no associations were found between PUFA ratio (HRT users: 8.62; HRT nonusers: 8.27) and BMD (86).

In the Framingham Osteoporosis Study, significant associations between quartiles of dietary ratios of n–6 to n–3 PUFAs and BMD were not found in either men or women. However, men in the highest quartile of AA intake experienced significantly less loss of BMD at the femur neck over a 4-y follow-up period when they were also classified as being in 1 of the 3 highest quartiles for EPA + DHA intake (12), implying a benefit to a lower ratio of AA to EPA + DHA when AA is high.

Fish consumption and BMD.

The observational studies that used BMD as a surrogate measure of risk of fracture to determine the association between fish and bone health have provided conflicting results. A study of 632 postmenopausal Japanese women found no significant difference in lumbar spine BMD between women who consumed fish >5 times/wk and those who consumed fish <5 times/wk (16). The authors of this study did not clarify the type of fish consumed, but do suggest that both groups may have exceeded the intake level necessary to provide any further benefit. In Japan, a dietary goal of 1 g EPA + DHA/d has been recommended by the National Institute of Health and Nutrition, which may help to explain the already high quantities of fish intake in this study (33). Another large cohort of 5201 men and women found a negative effect of more frequent intake of tuna and other fish, citing a slightly lower average femur neck BMD between the highest (≥3 servings/wk, corresponding to 0.59 g EPA + DHA/d) and lowest (<1 serving/mo, 0.05 g EPA + DHA/d) quintiles of intake where average intake was 1.6 servings/wk (15). There was no association between EPA + DHA intake and risk of fracture in this population. In this study of older (average age 72.8 y), community-dwelling participants, although more frequent fish intake was negatively associated with femur neck BMD, these associations were not paralleled with an increased fracture incidence when stratified by intake of EPA + DHA (15).

In direct contrast, 3 prospective studies—2 cohorts of Chinese populations and the Framingham Osteoporosis cohort—reported a positive effect of higher fish consumption on BMD (10–12). An intake of 250 g/wk or greater (roughly 3 servings/wk) of seafood, including fish and shellfish, was associated with a greater total body and hip BMD in rural Chinese postmenopausal women (10). Similarly, a dose-dependent linear relation was observed between intakes of sea fish (nonfreshwater or shellfish) and BMD or bone mineral content at the whole body, total hip, femur neck, trochanter, and intertrochanter in 685 postmenopausal women (11). This association corresponded to a significantly lower odds ratio of osteoporosis at the whole body, total hip, femur neck, and intertrochanter for women consuming the highest (64.7 g/d) compared with those in the lowest (0.6 g/d) quintile of intake of sea fish (11). In the Framingham Osteoporosis Study, consumption of ≥3 servings of fish/wk was associated with the maintenance of femur neck BMD in older men and women over a 4-y follow-up period (12). This association can be mainly attributed to dark fish consumption, because both men and women with high intakes of dark fish lost significantly less femur neck BMD than did men and women with moderate or low intakes. These associations were also observed with total fish intake in both men and women, but were not significant. In the Framingham Osteoporosis Study, the type of fish consumed was mainly tuna and white and other fish, while dark fish accounted for 12% of intake in women and 17% in men (12).

The conflicting results in these studies of fish consumption and BMD may be attributed to the type of fish consumed. In those prospective studies citing no benefit with fish intake, the subtype of fish was not classified (16, 80) or was classified as either tuna or other broiled or baked fish or fried fish (15). Benefits were observed in those studies quantifying fish and shellfish (10), sea fish (11), or total fish, dark fish + tuna, dark fish, or tuna intakes (12). The positive effects of fish consumption in these studies may be attributed to their displacement of low-quality food items from the diet, the high vitamin D concentrations and/or the high content of long chain n–3 PUFAs found within these types of fish.

Findings from RCTs.

Although observational studies of the population identify associations between dietary habits and bone health, they do not allow for causal relations to be investigated. A few RCTs have determined whether a cause and effect relation exists between dietary PUFA intake and markers of bone health in postmenopausal women. Most studies have shown either a benefit or a null effect of PUFA supplementation to bone health. Aspects to consider when reviewing findings from RCTs are shown in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Aspects to consider when reviewing RCTs assessing the effect of PUFA intake and bone health1

| Inclusion criteria | Participant characteristics: age, sex, ethnicity, BMI, physical activity, and previous fracture incidence are all variables that modulate bone health |

| Menopausal status: bone turnover is largely imbalanced during the 5- to 10-y period coinciding with the menopausal transition, with different rates of bone loss occurring at different skeletal sites (94) | |

| HRT use: dietary fats may act in concert with exogenous estrogens | |

| Anti-fracture medication: drugs such as bisphosphonates or selective estrogen receptor modulators will impact the efficiency of a nutritional intervention | |

| Baseline dietary patterns | Habitual PUFA intake and supplement use: lifelong exposure to certain PUFAs may impact the ability of an intervention to alter bone health above a threshold |

| Baseline calcium and vitamin D: most RCTs provide all groups with calcium and vitamin D supplements, which may mask any additional effect of an intervention if baseline values are lower than recommended | |

| Intervention | PUFA intervention: PUFA type and source (food or supplement), PUFA amount, PUFA ratio |

| Study length: experimental intervention must be of sufficient duration to detect changes in the primary outcome measure | |

| Primary outcome measure | Imaging technique used: BMD by DXA, 3-dimensional quantification of bone structure and strength by HR-pQCT |

| Site-specific effects: regions of the skeleton may not respond uniformly to an intervention (e.g., hip, lumbar spine, appendicular limbs) | |

| Biochemical markers of bone turnover: including circadian variation of markers, sampling in a fed or fasted-state, intra-individual variability. To reduce variability, it is useful to measure multiple markers as well as the longitudinal change in markers in the same subject over time |

BMD, bone mineral density; HR-pQCT, high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography; HRT, hormone replacement therapy; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

One of the first trials investigated the effects of either evening primrose oil (EPO), a natural source of the n-6 PUFA gamma-linoleic acid, fish oil, or the combination of oils on serum biochemical markers of elderly women with osteoporosis (89). In this study, 4 g fish oil/d for 16 wk showed a beneficial effect in women through an increase in serum osteocalcin and procollagen concentrations, biochemical markers of bone turnover and formation, respectively, compared with no supplementation (89). The combination of aerobic exercise and 1 g EPA + DHA supplementation caused an increase in BMD at the lumbar spine and femur neck after 24 wk in postmenopausal women (90). Coinciding with this increase in BMD from baseline, PGE2 concentrations were decreased, and significant negative correlations were observed between BMD of lumbar spine or femur neck and concentrations of PGE2. This correlation suggests that higher PUFA intake and aerobic exercise may increase bone mineral by reducing inflammatory eicosanoid production. In support of this mechanism, TNF-α and IL-6 concentrations were attenuated with EPA + DHA supplementation alone and when combined with exercise (90). More support of long chain n–3 PUFAs on bone health comes from a study investigating the effect of 2.52 g EPA/d and 1.68 g DHA/d compared with 4 g safflower oil control/d in postmenopausal women receiving aromatase inhibitors for the treatment of estrogen-positive breast cancer (91). Following 12 wk of treatment, women in the EPA + DHA group experienced a significant decrease in serum C-terminal telopeptide, and this marker of bone resorption was positively correlated with serum AA and with serum long chain n–6-to-n–3 fatty acid ratios and negatively correlated with serum EPA + DHA concentrations (91). Of importance to note, all women received a 1000-mg calcium supplement and 800 IU vitamin D/d, and not all women experienced a similar trend in response, suggesting that these women were nonresponders and were retroactively removed from the analyses. Although the women enrolled in the previously discussed RCTs were not provided supplemental calcium or vitamin D, baseline concentrations of calcium and serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D were similar among all groups (89–91).

Conversely, ancillary analysis of a large RCT consisting of 190 men and women consuming either 1.48 g EPA + DHA/d or olive oil placebo found no change in C-terminal telopeptide (92). Although average fasting plasma concentrations of n–3 PUFAs increased over the 12-wk study, no association was found with this marker of bone resorption. This finding could be due to the variability in participant characteristics, which included both men and women of a wide age range, of which only 75% were over 50 y. It is possible that men may respond differently to EPA + DHA supplementation than women, and the hormonal status of a woman may alter her responsiveness.

Unlike studies of long chain n–3 PUFA supplementation, there is insufficient evidence to suggest a positive effect of ALA on postmenopausal bone health. In 1 study of 179 women with at least 6 mo of amenorrhea, neither 40 g of flaxseed or wheat germ placebo incorporated into the diet prevented the progressive bone loss observed over 12 mo in early menopausal women (93). Although this study saw no change in lumbar or femoral neck BMD by DXA between the 2 groups, this could be attributed to the good health of the participants and their interest in health and diet, inferred by the recruitment criteria of the study. Also, bone loss at the hip and lumbar spine over the menopausal transition is most dramatic during late perimenopause (3–11 mo amenorrhea) and postmenopause (>12 mo amenorrhea) (94), which coincides with the relatively early stage the menopausal transition women from this study were classified in (93). Similarly, no change in lumbar or hip BMD was observed after 12 wk of resistance training with and without the supplementation of 30 mL flaxseed oil/d (~6.9 g ALA/d) (95). The design of this trial could not distinguish the effect of diet alone on bone health because all 51 Canadian men and women, 23 of whom were postmenopausal females, underwent resistance training. Flaxseed supplementation trials of 40 g whole ground flaxseed/d for 3 mo (roughly 9.2 g ALA/d) (96) and 25 g/d for 4 mo (roughly 5.8 g ALA/d) (97) in postmenopausal women resulted in no effect on biomarkers of bone metabolism when compared with their wheat placebo or wheat and soy supplementation controls, respectively.

To establish the long-term effect of a complex combination of PUFAs in an elderly population of women with osteoporosis, supplementation with 6 g EPO and fish oil was compared with 6 g coconut oil/d over 18 mo (98). The PUFA supplement consisted of ~68% n–6 fatty acid and 7% long chain n–3 fatty acid, whereas the coconut oil treatment was rich in SFAs. Both interventions resulted in significant increases in markers of bone formation (procollagen, bone specific alkaline phosphatase) and decreases in markers of bone turnover (osteocalcin) and resorption (deoxypyridinoline). The similar findings observed with both treatments may be attributed to the calcium supplement (600 mg) provided to all women enrolled in the study. Upon entrance into the study, the average daily calcium intake was 653 ± 249 mg, below the 1998 RDA of 800 mg and the current DRI (United States, Canada) of 1200 mg for women over 70 y of age. Thus, their bone health likely benefited from this calcium supplementation, rather than the fatty acid intervention. Interestingly, PUFA supplementation with EPO was able to preserve lumbar spine BMD and increase femur neck BMD over the 18-mo treatment period, whereas coconut oil caused a 3.2% and 2.1% decrease in lumbar spine and femur neck BMD, respectively. Because of the beneficial effects observed with PUFA supplementation, 21 women remained in the study for a total of 36 mo, and those in the coconut oil group were reallocated to receive EPO and fish oil. After 36 mo, lumbar spine and femur neck BMD was preserved in those women who had consistently been supplemented with the PUFA combination and was increased in the women switched to the PUFA supplement (98). In contrast, a study of 45 postmenopausal women consuming either 1 g calcium with 4 g EPO and 440 mg fish oil, or calcium alone found a decrease in total body BMD by 1% in both groups over 12 mo and no between-group differences in urinary markers of bone turnover (99). The women recruited in this study already had an average baseline calcium intake of ~900 mg/d, which may have masked any effect attributed to the fatty acid supplementation.

To our knowledge, the only randomized crossover control trial to assess the effect of the ratio of n–6 to n–3 PUFAs on bone health comes as ancillary data from a larger study designed to evaluate the effect of PUFAs in the diet on cardiovascular disease (100). Three diets were used, lasting a period of 6 wk and separated by a 3-wk washout period. All diets consisted of 35% fat as energy based on 2400 kcal/d and differed by PUFA ratio. As a control, created to mimic the average American diet, a ratio of 9.5 for LA to ALA was consumed. Two experimental diets consisted of ratios of 3.5 and 1.6, respectively. At study endpoint, the lowest ratio of dietary n–6 to n–3 yielded a significantly lower serum N-terminal telopeptide concentration. This treatment diet also reduced serum concentrations of the inflammatory marker, TNF-α, and a positive correlation was observed between N-terminal telopeptide concentrations and TNF-α concentrations across all diets. Although bone resorption rates seem to be positively affected by PUFA ratio, serum bone specific alkaline phosphatase concentrations were not changed with this diet. Although the crossover design is powerful, this study included 23 participants, of which only 3 were postmenopausal women and all were at high risk for cardiovascular disease. These results suggest the need for more controlled feeding studies with crossover design, particularly studies including postmenopausal women, to evaluate how the quantity and ratio of n–6 to n–3 PUFAs modulates bone health.

Summary

Findings from human studies largely show that greater intake of total PUFAs, total n–6 PUFAs, total n–3 PUFAs, and fish is associated with higher BMD or lower risk of fragility fracture in women (Table 4). Less consistent benefits to bone health are associated with higher intake of long chain n–3 PUFAs or when the dietary ratio of n–6 to n–3 PUFAs is considered. The strongest evidence for benefits to bone is from studies of fish intake. Regular consumption of fish and seafood not only provides high quantities of PUFAs but can also be rich sources of protein, vitamin D, calcium, and other vitamins and minerals, all of which are necessary for the maintenance of strong, fracture-resistant bones.

TABLE 4.

Summary of the findings concerning PUFA intakes and bone-related outcomes1

| PUFA | DRI males, females 51–70 y | Quantity | Bone-related outcome | Reference |

| Total PUFAs | 15.6 g/d, 12.1 g/d | Quartile 1 (0.71–5.16% energy) vs. quartile 4 (7.90–31.84% energy) | Decreased total fracture risk | (76) |

| Quintile 1 (7.9 g/d) vs. quintile 5 (13.9 g/d) | Decreased hip fracture risk | (13) | ||

| Quartile 1 (≤7.11 g/d) vs. quartile 4 (>10.24 g/d) | Increased lumbar spine BMD2 | (83) | ||

| 11.26 g/d | No association with lumbar spine and total body BMD2 | (86) | ||

| Total n–6 PUFAs | 14 g/d, 11 g/d | Quartile 1 (0.61 g/d) vs. quartile 4 (6.94 g/d) | Decreased total fracture risk | (76) |

| Quintile 1 (6.9 g/d) vs. quintile 5 (12.4 g/d) | Decreased hip fracture risk | (13) | ||

| Quartile 1 (4.89 g/d) vs. quartile 4 (6.89 g/d) | Increased lumbar spine and total body BMD2 | (83) | ||

| Tertile 1 (<8.51 g/d) vs. tertile 3(>11.46 g/d) | Decreased total body BMD2 | (86) | ||

| LA | 14 g/d, 11 g/d | Quintile 1 (6.8 g/d) vs. quintile 5 (12.1 g/d) | Decreased hip fracture risk | (13) |

| Quartile 1 (4.8 g/d) vs. quartile 4 (6.77 g/d) | Increased lumbar spine and total body BMD2 | (83) | ||

| 9.78 g/d | No association with lumbar spine and total body BMD2 | (86) | ||

| Total n–3 PUFAs | 1.6 g/d, 1.1 g/d | >1.27 g/d | Increased femur neck and total femur BMD | (84) |

| Quintile 1 (0.9 g/d) vs. quintile 5 (1.6 g/d) | Decreased hip fracture risk | (13) | ||

| Quartile 1 (1.31 g/d) vs. quartile 4 (2.21 g/d) | Increased total body BMD2 | (83) | ||

| Mean: 2.7 g/d | Increased lumbar spine BMD | (85) | ||

| Tertile 1 (<0.99 g/d) vs. tertile 3 (>1.40 g/d) | Decreased total body BMD2 | (86) | ||

| ALA | 1.6 g/d, 1.1 g/d | 40 g flaxseed/d (12 mo) | No benefit to bone loss at lumbar spine or femur neck | (93) |

| Quartile 1 (0.08 g/d) vs. quartile 4 (0.84 g/d) | Decreased total fracture risk | (76) | ||

| Quintile 1 (0.7 g/d) vs. quintile 5 (1.2 g/d) | No change in fracture risk | (13) | ||

| Quartile 1 (1.02 g/d) vs. quartile 4 (1.73 g/d) | Increased lumbar spine BMD2 | (83) | ||

| 1.11 g/d | No association with lumbar spine and total body BMD2 | (86) | ||

| EPA + DHA | Up to 10% of AMDR consumed as EPA and/or DHA | 4 g fish oil/d compared with 4 g EPO/d (16 wk) | Increased concentrations of serum OC and procollagen | (89) |

| Decreased concentrations of serum BSAP | ||||

| Quintile 1 (0.145 g/d) vs. quintile 5 (0.519 g/d) from fish | No effect on BMD | (15) | ||

| No effect on hip fracture risk | ||||

| Quartile 1 (0 g/d) vs. quartile 4 (0.09 g/d) | Decreased hip fracture risk | (76) | ||

| Increased total fracture risk3 | ||||

| 1.0 g/d (24 wk) | Decreased concentrations of TNFα and IL-6 | (90) | ||

| 1.48 g/d (12 wk) | No change in concentration of CTX | (92) | ||

| Quintile 1 (0.07 g/d) vs. quintile 5 (0.37 g/d) | Decreased hip fracture risk3 | (13) | ||

| 0.15 g/d From supplements | Increased lumbar spine BMD | (87) | ||

| 0.18 g/d | No association with lumbar spine and total BMD2 | (86) | ||

| Ratio of n–6 to n–3 PUFAs | 8.75:1, 10:1 | 6 g EPO + fish oil combination/d (18 mo) | Increased concentrations of serum procollagen and BSAP | (98) |

| Decreased concentrations of serum OC and urinary deoxypyridinoline | ||||

| Preservation of lumbar spine BMD | ||||

| Increased femur neck BMD | ||||

| 4 g EPO + 0.44 g fish oil/d (12 mo) | No benefit to total body BMD loss | (99) | ||

| Mean ± SD n–6 to n–3 PUFA: 7.9 ± 2.2 | Inverse association with total hip (LA to ALA only) and lumbar spine BMD2 | (88) | ||

| Mean ± SD LA to ALA: 8.4 ± 2.3 | ||||

| LA to ALA: 9.5 vs. 3.5 vs. 1.6 (6 wk) | Decreased concentrations of NTx and TNFα | (100) | ||

| n–6 to n–3 PUFAs > 6.43 | Decreased total fracture risk | (76) | ||

| Greater AA intake when EPA + DHA intake is above 0.14 g/d | Increased femur neck BMD | (12) | ||

| LA to ALA: 3.61 to >5.13 | Inverse association (NS) with lumbar spine BMD2 | (83) | ||

| Mean n–6 to n–3 PUFAs: 8.27 | Negative association with total body BMD2 | (86) | ||

| Mean LA to ALA: 9.15 | ||||

| Fish | 2 servings of fish/wk. Suggested sources: char, herring, mackerel, salmon, sardines, trout | 3–4 servings/wk | Decreased hip fracture risk | (101) |

| Quartile 1 (<1 serving/mo) vs. quartile 4 (>1 serving/wk) | Decreased hip fracture risk | (9) | ||

| ≤5 servings/wk vs. >5 servings/wk | No difference in lumbar spine BMD | (16) | ||

| >250 g Seafood/wk | Increased hip and total body BMD | (10) | ||

| Quintile 1 (0.6 g/d) vs. quintile 5 (64.7 g/d) from sea fish | Positive dose-dependent relation with hip, spine, and whole body BMD and BMC | (11) | ||

| Decreased hip and total fracture risk | ||||

| Quartile 1 (<1 serving/mo) vs. quartile 4 (≥3 servings/wk) | Decreased femur neck BMD | (15) | ||

| ≥3 servings/wk | Maintenance of femur neck BMD | (12) | ||

| Quintile 1 (<1 serving/mo) vs. quintile 5 (≥5 servings/wk) | Decreased hip fracture risk3 | (13) |

AA, arachidonic acid; ALA, α-linolenic acid; AMDR, acceptable macronutrient distribution range; BMC, bone mineral content; BMD, bone mineral density; BSAP, bone-specific alkaline phosphatase; CTX, C-terminal telopeptide; EPO, evening primrose oil; HRT, hormone replacement therapy; LA, linoleic acid; OC, osteocalcin; NTx, N-terminal telopeptide.

Women not receiving HRT only.

Significant associations were lost after full multivariate adjustment of the model.

Acknowledgments

WE Ward is a Canada Research Chair in Bone and Muscle Development. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used: AA, arachidonic acid; ALA, α-linolenic acid; BMD, bone mineral density; EPO, evening primrose oil; HR-pQCT, high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography; HRT, hormone replacement therapy; LA, linoleic acid; NHS, Nurses’ Health Study; RCT, randomized controlled trial; WHI, Women’s Health Initiative.

References

- 1.Burge R, Dawson-Hughes B, Solomon DH, Wong JB, King A, Tosteson A. Incidence and economic burden of osteoporosis-related fractures in the United States, 2005–2025. J Bone Miner Res 2007;22:465–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abimanyi-Ochom J, Watts JJ, Borgstrom F, Nicholson GC, Shore-Lorenti C, Stuart AL, Zhang Y, Iuliano S, Seeman E, Prince R, et al. Changes in quality of life associated with fragility fractures: Australian arm of the International Cost and Utility Related to Osteoporotic Fractures Study (AusICUROS). Osteoporos Int 2015;26:1781–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borgström F, Zethraeus N, Johnell O, Lidgren L, Ponzer S, Svensson O, Abdon P, Ornstein E, Lunsjo K, Thorngren KG, et al. Costs and quality of life associated with osteoporosis-related fractures in Sweden. Osteoporos Int 2006;17:637–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barcenilla-Wong AL, Chen JS, Cross MJ, March LM. The impact of fracture incidence in health related quality of life among community-based postmenopausal women. J Osteoporos 2015;2015:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hagino H, Nakamura T, Fujiwara S, Oeki M, Okano T, Teshima R. Sequential change in quality of life for patients with incident clinical fractures: a prospective study. Osteoporos Int 2009;20:695–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hallberg I, Rosenqvist AM, Kartous L, Lofman O, Wahlstrom O, Toss G. Health- related quality of life after osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int 2004;15:834–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnell O, Kanis JA. An estimate of the worldwide prevalence and disability associated with osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int 2006;17:1726–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lau EM, Lee JK, Suriwongpaisal P, Saw SM, Das De S, Khir A, Sambrook P. The incidence of hip fracture in four Asian countries: the Asian Osteoporosis Study (AOS). Osteoporos Int 2001;12:239–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feskanich D, Willett WC, Colditz GA. Calcium, vitamin D, milk consumption, and hip fractures: a prospective study among postmenopausal women. Am J Clin Nutr 2003;77:504–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zalloua PA, Hsu YH, Terwedow H, Zang T, Wu D, Tang G, Li Z, Hong X, Azar ST, Wang B, et al. Impact of seafood and fruit consumption on bone mineral density. Maturitas 2007;56:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen YM, Ho SC, Lam SS. Higher sea fish intake is associated with greater bone mass and lower osteoporosis risk in postmenopausal Chinese women. Osteoporos Int 2010;21:939–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farina EK, Kiel DP, Roubenoff R, Schaefer EJ, Cupples LA, Tucker KL. Protective effects of fish intake and interactive effects of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid intakes on hip bone mineral density in older adults: the Framingham Osteoporosis Study. Am J Clin Nutr 2011;93:1142–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Virtanen JK, Mozaffarian D, Willett WC, Feskanich D. Dietary intake of polyunsaturated fatty acids and risk of hip fracture in men and women. Osteoporos Int 2012;23:2615–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Calderon-Garcia JF, Moran JM, Roncero-Martin R, Rey-Sanchez P, Rodriguez-Velasco FJ, Pedrera-Zamorano JD. Dietary habits, nutrients and bone mass in Spanish premenopausal women: the contribution of fish to better bone health. Nutrients 2013;5:10–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Virtanen JK, Mozaffarian D, Cauley JA, Mukamal JK, Robbins J, Siscovick DS. Fish consumption, bone mineral density, and risk of hip fracture among older adults: the cardiovascular health study. J Bone Miner Res 2010;25:1972–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muraki S, Yamamoto S, Ishibashi J, Oka H, Yoshimura N, Kawaguchi H, Nakamura K. Diet and lifestyle associated with increased bone mineral density: cross-sectional study of Japanese elderly women at an osteoporosis outpatient clinic. J Orthop Sci 2007;12:317–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fujiwara S, Kasagi F, Yamada M, Kodama K. Risk factors for hip fracture in a Japanese cohort. J Bone Miner Res 1997;12:998–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids (Macronutrients). Washington (DC): The National Academies Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burdge GC, Wootton SA. Conversion of alpha-linolenic acid to eicosapentaenoic, docosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acids in young women. Br J Nutr 2002;88:411–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kris-Etherton PM, Taylor DS, Yu-Poth S, Huth P, Moriarty K, Fishell V, Hargrove RL, Zhao G, Etherton TD. Polyunsaturated fatty acids in the food chain in the United States. Am J Clin Nutr 2000; 71(1, Suppl)179S–88S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simopoulos AP. Evolutionary aspects of diet, the omega-6/omega-3 ratio and genetic variation: nutritional implications for chronic diseases. Biomed Pharmacother 2006;60:502–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Health Canada. Canadian Community Health Survey, Cycle 2.2, Nutrition. Nutrient Intakes from Food Provincial, Regional and National Summary Data Tables, Volume 1, 2, and 3. Ottawa, Canada: Minister of Health Canada; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 23.McDonald BE. Canola oil: nutritional properties. Winnipeg, Canada: Canola Council of Canada; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 24.List GR. Effects of nutrition labeling on edible oil processing and consumption patterns in the US. Lipid Technology 2013;25:55–7. [Google Scholar]

- 25.FAO-WHO. Fats and fatty acids in human nutrition. FAO Report of an expert consultation. FAO Food Nutr Pap 2010;91:1–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kris-Etherton PM, Innis S, American Dietetic Association, Dietitians of Canada. Position of the American Dietetic Association and Dietitians of Canada: dietary fatty acids. J Am Diet Assoc 2007;107:1599–611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Health Canada (2011) Eating well with Canada’s Food Guide – A Resource for Educators and Communicators. [cited 2015 Sep 4]. Available at: http://www.healthcanada.gc.ca/foodguide.

- 28.Kris-Etherton PM, Harris WS, Appel LJ, American Heart Association. Fish consumption, fish oil, omega-3 fatty acids, and cardiovascular disease. Circulation 2002;106:2747–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.American Diabetes Association, Bantle JP, Wylie-Rosett J, Albright AL, Apovian CM, Clark NG, Franz MJ, Hoogwerf BJ, Luchtenstein AH, Mayer-Davis E, Mooradian AD, et al. Nutrition recommendations and interventions for diabetes: a position statement of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2008;31: Suppl 1:S61–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martin A. The “apports nutritionnels conseilles (ANC)” for the French population. Reprod Nutr Dev 2001;41:119–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nordic Council of Ministers. Nordic nutrition recommendations 2012. Integrating nutrition and physical activity, version 5 edition. [cited 2015 Sep 4]. Available from: https://www.norden.org/en/theme/nordic-nutrition-recommendation/nordic- nutrition-recommendations-2012.

- 32.National Heart Foundation of Australia. Position statement on fish, fish oils, n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and cardiovascular health. Heart Foundation. [cited 2015 Sep 4]. Available from: http://www.heartfoundation.org.au/SiteCollectionDocuments/Fish-position-statement.pdf.

- 33.Tsubota-Utsagi M, Imai E, Nakade M, Tsuboyama-Kasaoka N, Morita A, Tokudome S. Dietary reference intakes for Japanese. National Institute of Health and Nutrition. [cited 2015 Sep 4]. Available from: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/bunya/kenkoy/sessyu-kijun.html.

- 34.Mozaffarian D, Micha R, Wallace S. Effects on coronary heart disease of increasing polyunsaturated fat in place of saturated fat: a systematic review and meta- analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS Med 2010;7:e1000252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Siris ES, Chen YT, Abbott TA, Barrett-Conner E, Miller PD, Wehren LE, Berger ML. Bone mineral density thresholds for pharmacological intervention to prevent fractures. Arch Intern Med 2004;164:1108–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cranney A, Jamal SA, Tsang JF, Josse RG, Leslie WD. Low bone mineral density and fracture burden in postmenopausal women. CMAJ 2007;177:575–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Langsetmo L, Goltzman D, Kovacs CS, Adachi JD, Hanley DA, Kreiger N, Josse R, Papaioannou A, Olszynski WP, Jamal SA, et al. Repeat low-trauma fractures occur frequently among men and women who have osteopenic BMD. J Bone Miner Res 2009;24:1515–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kanis JA, Oden A, Johansson H, Borgstrom F, Strom O, McCloskey E. FRAX and its applications to clinical practice. Bone 2009;44:734–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Siminoski K, Leslie WD, Frame H, Hodsman A, Josse RG, Khan A, Lentle BC, Levesque J, Lyons DJ, Tarulli G, et al. Recommendations for bone mineral density reporting in Canada: a shift to absolute fracture risk assessment. J Clin Densitom 2007;10:120–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.World Health OrganizationAssessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis. WHO Technical Report Series 843. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 1994. [PubMed]

- 41.Sornay-Rendu E, Boutroy S, Munoz F, Delmas PD. Alterations of cortical and trabecular architecture are associated with fractures in postmenopausal women, partially independent of decreased BMD measured by DXA: the OFELY study. J Bone Miner Res 2007;22:425–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Seibel MJ. Biochemical markers of bone turnover: part I: biochemistry and variability. Clin Biochem Rev 2005;26:97–122. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Laneuville O, Breuer DK, Xu N, Huang ZH, Gage DA, Watson JT, Lagarde M, DeWitt DL, Smith WL. Fatty acid substrate specificities of human prostaglandin- endoperoxide H synthase-1 and -2. Formation of 12-hydroxy-(9Z, 13E/Z, 15Z)- octadecatrienoic acids from alpha-linolenic acid. J Biol Chem 1995;270:19330–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Coetzee M, Haag M, Claassen N, Kruger MC. Stimulation of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) production by arachidonic acid, oestrogen and parathyroid hormone in MG-63 and MC3T3–E1 osteoblast-like cells. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 2005;73:423–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baylink TM, Mohan S, Fitzsimmons RJ, Baylink DJ. Evaluation of signal transduction mechanisms for the mitogenic effects of prostaglandin E2 in normal human bone cells in vitro. J Bone Miner Res 1996;11:1413–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lomri A, Marie PJ. Bone cell responsiveness to transforming growth factor beta, parathyroid hormone, and prostaglandin E2 in normal and postmenopausal osteoporotic women. J Bone Miner Res 1990;5:1149–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Take I, Kobayashi Y, Yamamoto Y, Tsuboi H, Ochi T, Uematsu S, Okafuji N, Kurihara S, Udagawa N, Takahashi N. Prostaglandin E2 strongly inhibits human osteoclast formation. Endocrinology 2005;146:5204–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tintut Y, Parhami F, Tsingotjidou A, Tetradis S, Territo M, Demer LL. 8-Isoprostaglandin E2 enhances receptor-activated NFkappa B ligand (RANKL)- dependent osteoclastic potential of marrow hematopoietic precursors via the cAMP pathway. J Biol Chem 2002;277:14221–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wani MR, Fuller K, Kim NS, Choi Y, Chambers T. Prostaglandin E2 cooperates with TRANCE in osteoclast induction from hemopoietic precursors: synergistic activation of differentiation, cell spreading, and fusion. Endocrinology 1999;140:1927–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Flanagan AM, Stow MD, Kendall N, Brace W. The role of 1,25- dihydroxycholecalciferol and prostaglandin E2 in the regulation of human osteoclastic bone resorption in vitro. Int J Exp Pathol 1995;76:37–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lader CS, Flanagan AM. Prostaglandin E2, interleukin 1-alpha, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha increase human osteoclast formation and bone resorption in vitro. Endocrinology 1998;139:3157–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kamel MA, Picconi JL, Lara-Castillo N, Johnson ML. Activation of beta-catenin signaling in MLO-Y4 osteocytic cells versus 2T3 osteoblastic cells by fluid flow shear stress and PGE2: Implications for the study of mechanosensation in bone. Bone 2010;47:872–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Klein-Nulend J, van der Plas A, Semeins CM, Ajubi NE, Frangos JA, Nijweide PJ, Burger EH. Sensitivity of osteocytes to biomechanical stress in vitro. FASEB J 1995;9:441–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Saunders MM, Taylor AF, Du C, Zhou Z, Pellegrini VD Jr, Donahue HJ. Mechanical stimulation effects on functional end effectors in osteoblastic MG-63 cells. J Biomech 2006;39:1419–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Galea GL, Sunters A, Meakin LB, Zaman G, Sugiyama T, Lanyon LE, Price JS. Sost down-regulation by mechanical strain in human osteoblastic cells involves PGE2 signaling via EP4. FEBS Lett 2011;585:2450–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Simopoulos AP. The omega-6/omega-3 fatty acid ratio, genetic variation, and cardiovascular disease. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2008;17: Suppl 1:131–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Simopoulos AP. The importance of the omega-6/omega-3 fatty acid ratio in cardiovascular disease and other chronic disease. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2008;233:674–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang D, Dubois RN. Eicosanoids and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2010;10:181–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tessaro FH, Ayala TS, Marins JO. Lipid mediators are critical in resolving inflammation: a review of the emerging roles of eicosanoids in diabetes mellitus. BioMed Res Int 2015;2015:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dawczynski C, Massey KA, Ness C, Kiehntopf M, Stepanow S, Platzer M, Grun M, Nicolaou A, Jahreis G. Randomized placebo-controlled intervention with n-3 LC- PUFA-supplemented yoghurt: effects on circulating eicosanoids and cardiovascular risk factors. Clin Nutr 2013;32:686–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Greene ER, Huang S, Serhan CN, Panigrahy D. Regulation of inflammation in cancer by eicosanoids. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat 2011;96:27–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kim JE, Ahn MW, Baek SH, Lee IK, Kim YW, Kim JY, Dan JM, Park SY. AMPK activator, AICAR, inhibits palmitate-induced apoptosis in osteoblast. Bone 2008;43:394–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Elbaz A, Wu X, Rivas D, Gimble JM, Duque G. Inhibition of fatty acid biosynthesis prevents adipocyte lipotoxicity on human osteoblasts in vitro. J Cell Mol Med 2010;14:982–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang D, Haile A, Jones LC. Dexamethasone-induced lipolysis increases the adverse effect of adipocytes on osteoblasts using cells derived from human mesenchymal stem cells. Bone 2013;53:520–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gunaratnam K, Vidal C, Boadle R, Thekkedam C, Duque G. Mechanisms of palmitate-induced cell death in human osteoblasts. Biol Open 2013;2:1382–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Diascro DD Jr, Vogel RL, Johnson TE, Witherup KM, Pitzenberger SM, Rutledge SJ, Prescott DJ, Rodan GA, Schmidt A. High fatty acid content in rabbit serum is responsible for the differentiation of osteoblasts into adipocyte-like cells. J Bone Miner Res 1998;13:96–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Coetzee M, Haag M, Joubert AM, Kruger MC. Effects of arachidonic acid, docosahexaenoic acid and prostaglandin E2 on cell proliferation and morphology of MG-63 and MC3T3–E1 osteoblast-like cells. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 2007;76:35–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Maurin AC, Chavassieux PM, Vericel E, Meunier PJ. Role of polyunsaturated fatty acids in the inhibitory effect of human adipocytes on osteoblastic proliferation. Bone 2002;31:260–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gimble JM, Robinson CE, Wu X, Kelly KA, Rodriguez BR, Kliewer SA, Lehmann JM, Morris DC. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma activation by thiazolidinediones induces adipogenesis in bone marrow stromal cells. Mol Pharmacol 1996;50:1087–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lecka-Czernik B, Gubrij I, Moerman EJ, Kajkenova O, Lipschitz DA, Monalagas SC, Jilka RL. Inhibition of Osf2/Cbfa1 expression and terminal osteoblast differentiation by PPARgamma2. J Cell Biochem 1999;74:357–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Maurin AC, Chavassieux PM, Meunier PJ. Expression of PPARgamma and beta/delta in human primary osteoblastic cells: influence of polyunsaturated fatty acids. Calcif Tissue Int 2005;76:385–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Priante G, Bordin L, Musacchio E, Clari G, Baggio B. Fatty acids and cytokine mRNA expression in human osteoblastic cells: a specific of arachidonic acid. Clin Sci (Lond) 2002;102:403–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bordin L, Priante G, Musacchio E, Giunco S, Tibaldi E, Clari G, Baggio B. Arachidonic acid-induced IL-6 expression is mediated by PKC alpha activation in osteoblastic cells. Biochemistry 2003;42:4485–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Musacchio E, Priante G, Buakovic A, Baggio B. Effects of unsaturated free fatty acids on adhesion and on gene expression of extracellular matrix macromolecules in human osteoblast-like cell cultures. Connect Tissue Res 2007;48:34–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bingham SA, Gill C, Welch A, Day K, Cassidy A, Khaw KT, Sneyd MJ, Key TJA, Roe L, Day NE. Comparison of dietary assessment methods in nutritional epidemiology: weighed records v. 24h recalls, food-frequency questionnaires and estimated-diet records. Br J Nutr 1994;72:619–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Orchard TS, Cauley JA, Frank GC, Neuhouser ML, Robinson JG, Snetselaar L, Tylavsky F, Wactawski-Wende J, Young AM, Lu B, et al. Fatty acid consumption and risk of fracture in the Women’s Health Initiative. Am J Clin Nutr 2010;92:1452–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.De Laet C, Kanis JA, Oden A, Johanson H, Johnell O, Delmas P, Eisman JA, Kroger H, Fujiwara S, Garnero P, et al. Body mass index as a predictor of fracture risk: a meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int 2005;16:1330–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Langsetmo L, Hitchcock CL, Kingwell EJ, Davison KS, Berger C, Forsmo S, Zhou W, Kreiger N, Prior JC. Canadian Multicenter Osteoporosis Study Research GroupPhysical activity, body mass index and bone mineral density-associations in a prospective population-based cohort of women and men: the Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study (CaMos). Bone 2012;50:401–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Darling AL, Millward DJ, Torgerson DJ, Hewitt CE, Lanham-New SA. Dietary protein and bone health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr 2009;90:1674–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Robinson JG, Stone NJ. Antiathersclerotic and antithrombotic effects of omega-3 fatty acids. Am J Cardiol 2006;98: 4A:39i–49i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Appleby P, Roddam A, Allen N, Key T. Comparative fracture risk in vegetarians and non-vegetarians in EPIC-Oxford. Eur J Clin Nutr 2007;61:1400–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Davey GK, Spencer EA, Appleby PN, Allen NE, Knox KH, Key TJ. EPIC-Oxford: lifestyle characteristics and nutrient intakes in a cohort of 33 883 meat-eaters and 31 546 non mean-eaters in the UK. Public Health Nutr 2003;6:259–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Järvinen R, Tuppurainen M, Erkkila AT, Penttinen P, Karkkainen M, Salovaara K, Jurvelin JS, Kroger H. Associations of dietary polyunsaturated fatty acids with bone mineral density in elderly women. Eur J Clin Nutr 2012;66:496–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rousseau JH, Kleppinger A, Kenny AM. Self-reported dietary intake of omega-3 fatty acids and associations with bone and lower extremity function. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009;57:1781–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nawata K, Yamauchi M, Takaoka S, Yamaguchi T, Sugimoto T. Association of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid intake with bone mineral density in postmenopausal women. Calcif Tissue Int 2013;93:147–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Harris M, Farrell V, Houtkooper L, Going S, Lohman T. Associations of polyunsaturated fatty acid intake with bone mineral density in postmenopausal women. J Osteoporos 2015;2015:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mangano K, Kerstetter J, Kenny A, Insogna K, Walsh SJ. An investigation of the association between omega-3 FA and bone mineral density among older adults: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey years 2005–2008. Osteoporos Int 2014;25:1033–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Weiss LA, Barrett-Conner E, von Muhlen D. Ratio of n-6 to n-3 fatty acids and bone mineral density in older adults: the Rancho Bernardo Study. Am J Clin Nutr 2005;81:934–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Vanpapendorp DH, Coetzer H, Kruger MC. Biochemical profile of osteoporotic patients on essential fatty acid supplementation. Nutr Res 1995;15:325–34. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tartibian B, Maleki BH, Kanaley J, Sadeghi K. Long-term aerobic exercise and omega-3 supplementation modulate osteoporosis through inflammatory mechanisms in post-menopausal women: a randomized, repeated measures study. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2011;8:71–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]