Abstract

Over half of all antibiotics target the bacterial ribosome—Nature's complex, 2.5 MDa nanomachine responsible for decoding mRNA and synthesizing proteins. Macrolide antibiotics, exemplified by erythromycin, bind the 50S subunit with nM affinity and inhibit protein synthesis by blocking the passage of nascent oligopeptides. Solithromycin (1), a third-generation semi-synthetic macrolide discovered by combinatorial copper-catalyzed click chemistry, was synthesized in situ by incubating either E. coli 70S ribosomes or 50S subunits with macrolidefunctionalized azide 2 and 3-ethynylaniline (3) precursors. The ribosome-templated in situ click method was expanded from a binary reaction (i.e., one azide and one alkyne) to a six-component reaction (i.e., azide 2 and five alkynes) and ultimately to a sixteen-component reaction (i.e., azide 2 and fifteen alkynes). The extent of triazole formation correlated with ribosome affinity for the anti (1,4)-regioisomers as revealed by measured Kd values. Computational analysis using the Site-Identification by Ligand Competitive Saturation (SILCS) approach indicated that the relative affinity of the ligands was associated with the alteration of macrolactone+desosamine-ribosome interactions caused by the different alkynes. Protein synthesis inhibition experiments confirmed the mechanism of action. Evaluation of the minimal inhibitory concentrations (MIC) quantified the potency of the in situ click products and demonstrated the efficacy of this method in the triaging and prioritization of potent antibiotics that target the bacterial ribosome. Cell viability assays in human fibroblasts confirmed 2 and four analogs with therapeutic indices for bactericidal activity over in vitro mammalian cytotoxicity as essentially identical to solithromycin (1).

Keywords: target-guided synthesis, in situ click chemistry, ribosome, macrolide antibiotics

INTRODUCTION

Bacterial resistance to antibiotics is a formidable 21st century global public health threat.1-3 If left unaddressed, we risk moving toward a “post-antibiotic” era.4 While resistance is a natural consequence of antibiotic use (and abuse), the rate at which pathogenic bacteria have evaded multiple classes of drugs (including those of last resort) has markedly outpaced the rate at which new drugs have been introduced. Macrolides are among the safest and most effective antibiotic classes. To date, three generations have been developed with only the lattermost targeting bacterial resistance.5,6

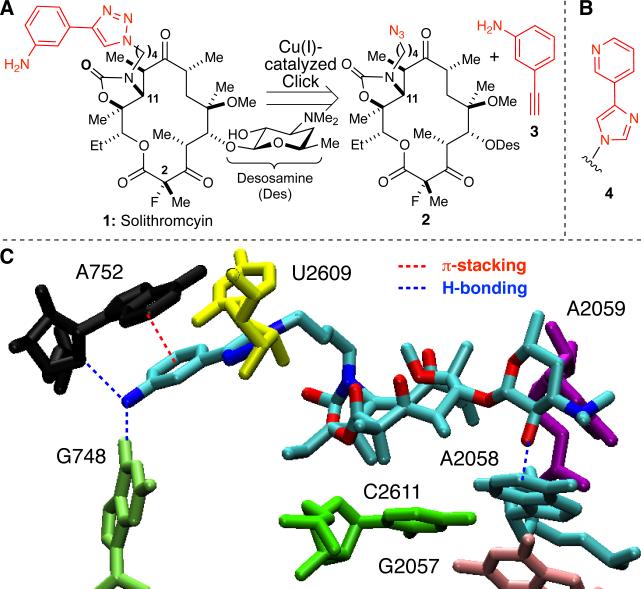

Solithromyin (1), one of the most potent macrolide antibiotics (Figure 1A), was prepared from the Cu(I)-catalyzed Huisgen [3+2] dipolar cycloaddition (i.e., “click”) reaction of azide 2 and 3-ethynylaniline (3).8 Inspiration for 1 came from the erythromycin-derived ketolide telithromycin, which possesses a structurally related pyridyl-imidazole side-chain 4 (Figure 1B).9

Figure 1.

(A) Retrosynthetic analysis of solithromycin (1) yields azide 2 and aromatic alkyne 3; (B) side-chain 4 from telithromycin; (C) Rendering of 1 and key 23S rRNA residues (Cate et al., PDB = 3ORB) using VMD.7

Over half of all known antibiotics, including macrolides, target the bacterial ribosome.10 Macrolides reversibly bind near the peptidyl transferase center of the 50S subunit with low nanomolar affinity and inhibit protein synthesis by blocking the passage of nascent oligopeptides.11,12 The structure of the E. coli 70S ribosome-solithromycin (1) complex confirmed both the location and mode of binding.13 Like other macrolides, 1 interacts with specific 23S rRNA residues via the macrolactone ring and desosamine sugar; moreover, the biaryl side-chain attached at N11 engages in π-stacking interactions with the A752-U2609 base pair and H-bonding with A752 and G748 (Figure 1C). Accordingly, we reasoned these molecular interactions could be leveraged in the ribosome-templated synthesis of solithromycin (1) from fragments 2 and 3 (Figure 1A); our target-guided synthesis strategy is illustrated in Scheme 1.14

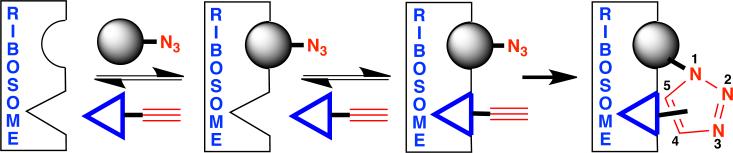

Scheme 1.

Ribosome-templated in situ click strategy for antibiotic synthesis. Sequential and proximal binding of azide- and alkyne-bearing fragments (e.g., 2 and 3, respectively) leads to irreversible anti (1,4)- and/or syn (1,5)-triazole formation by co-localization. The order in which the azide- and alkyne-functionalized fragments bind the target is determined by the individual binding affinities.

Target-guided in situ click chemistry is predicated on the selective, proximal binding of azide- and alkyne-bearing fragments, which lowers the activation energy of irreversible 1,2,3-triazole ligation by co-localization.15 Unlike the copper-catalyzed click reaction that exclusively provides the anti (1,4)-triazole16 or the ruthenium-catalyzed variant that exclusively provides the syn (1,5)-triazole,17 the in situ click process selectively provides the regioisomer that establishes optimal non-covalent interactions with the target (Scheme 1). Accordingly, the resultant cycloadduct is expected to have greater affinity for the target than the individual fragments.14 In this regard, in situ click chemistry represents an extension of fragment-based drug design wherein the target directly participates in the synthesis of its own inhibitor18,19 and has been successfully employed in the discovery of potent inhibitors for a number of targets, including: acetylcholine esterase,20,21,22,23 carbonic anhydrase,24 HIV-protease,25 chitinase,26 protein-protein interactions,27 DNA-recognition,28 EthR (a transcriptional regulator in M. tuberculosis),15,29,30 and a toxic RNA, which was formed in cellulo.31 Moreover, in situ click chemistry has been used extensively to create antibody-like protein capture agents.32-37

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

To test our hypothesis that bacterial ribosomes can template the Huisgen reaction, we synthesized azide 2 using known methods.38 Escherichia coli 70S ribosomes, 50S and 30S ribosomal subunits were isolated as described.39 After optimizing the concentrations of ribosomes, azide 2, and commercial 3-ethynylaniline (3) in tris(hydroxymethyl)-aminomethane (Tris) buffer, we found that 5 [.proportional]M 70S ribosomes or 50S subunits, 5 μM azide, and 5 mM alkyne at rt for 24–48 h resulted in the formation of 1 and its syn (1,5)-regioisomer (~2:1 ratio) in 12 ± 4-fold greater amounts than in the absence of 70S ribosome or 50S subunit (Figure 2). Analysis was performed on an Agilent 6520B Q-TOF LC-MS instrument wherein extracted ion chromatograms were used to locate and quantify the masses of interest (normalized to highest value).

Figure 2.

In situ click experiments with E. coli 70S ribosomes, 50S ribosomal subunits, 70S ribosomes with inhibitor azithromycin (AZY, 25 μM) and negative controls (30S ribosomal subunits, BSA, or buffer only). Mass counts (normalized) correspond to the combined anti-1 (solithromycin, SOL) and syn-1 regioisomer ions.

Retention times of both anti (1,4)- and syn (1,5)-regioisomers were confirmed independently by chemical synthesis via thermal cycloaddition; moreover, solithromycin (1) was exclusively prepared by Cu(I)-catalysis.40 Several lines of evidence strongly support the involvement of the large ribosomal subunit in the in situ click reaction: (1) in the absence of 70S ribosomes or 50S subunits (i.e., only buffer), there was 12 ± 4-fold less product formation, with the mass counts found corresponding to the thermal cycloaddition background reaction; (2) the 30S subunits, which do not possess a macrolide-binding site, also displayed mass counts similar to background; (3) the presence of ribosomal inhibitor azithromycin (AZY, 25 μM), which competes for the binding site with azide 2, blocks 70S ribosome-dependent product formation; (4) replacing ribosomes with bovine serum albumin (BSA), a standard negative control used to rule out non-specific binding, resulted in mass counts similar to those of the background cycloaddition; and finally, (5) the regioisomer ratio was ~1:1 in all control reactions (i.e., 30S, BSA, and buffer alone) and in the inhibition experiment with AZY, whereas in the presence of 70S ribosomes or 50S ribosomal subunits, the product ratio was 2:1 favoring 1. Such selectivity is a hallmark of the orientational (i.e., regioselective) nature of target-guided in situ click chemistry.29

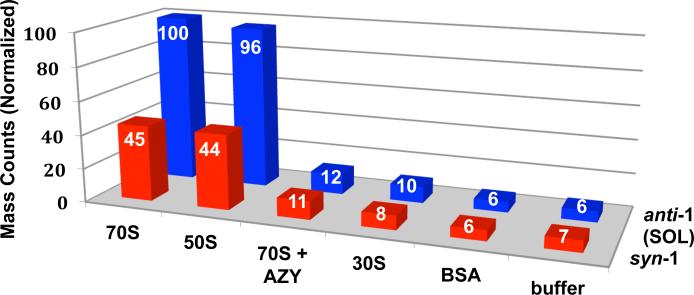

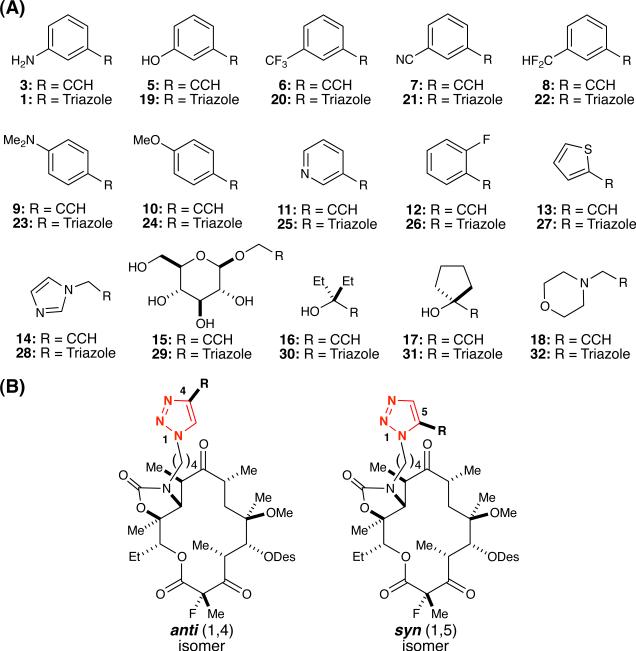

Having established the utility of in situ click chemistry in binary experiments (i.e., one azide, one alkyne) for the synthesis of solithromycin (1), we selected a small library of structurally diverse alkynes for competition experiments (Table 1A). The library of fifteen alkynes (Table 1A) contained both aromatic (e.g., 3, 5–14) and non-aromatic (e.g., 15–18) functionalities, including 3-ethynylaniline (3) used in the synthesis of solithromycin (1). Aromatic alkynes were selected based on the potential to engage in π-stacking interactions with the 23S rRNA A752-U2609 Watson-Crick base-pair, and to allow assessment of the impact of a hydrogen bonding network established between the aniline in 1 and A752 (PDB 3ORB).13 The non-aromatic alkynes included structural motifs that could bind rRNA via hydrogen bond donors (e.g., 15–17), acceptors (e.g., 15–18), or by forming electrostatic interactions (i.e., salt bridges) between the protonated amine in 32, derived from morpholine 18, and negatively-charged phosphates. As shown in Figure 2, triazoles from the in situ click reaction with azide 2 and the alkynes (Table 1A) can yield anti (1,4)- and/or syn (1,5)-regioisomers, depending on the positioning of alkyne fragments that make optimal interactions with rRNA (Table 1B, represented as ‘R’).

Table 1.

Structures of (A) alkyne fragments in the library and (B) regioisomeric anti (1,4)- and syn (1,5)-triazoles derived from in situ click experiments (R = Fragment).

Experiments were then undertaken to determine the ribosome binding affinity of azide 2 and the anti (1,4)-triazoles (Table 1B). To this end, anti-triazoles 1, 19–32 were prepared by Cu(I)-catalysis as template-guided synthesis only provides analytically detectable quantities.40 Products derived from the in situ click method are anticipated to possess greater target affinity, compared to the individual fragments, due to the additivity of binding energies (Scheme 1),14 such that triazoles formed in the greatest amounts (i.e., highest mass counts) should possess higher affinity. To quantify binding affinity, dissociation constants (Kd) of the anti-regioisomers of triazoles 1, 19–32 and azide 2 for 70S E. coli ribosomes were measured by an established fluorescence polarization competition assay using BODIPY-functionalized erythromycin.11 The results showed an eight-fold range of anti-triazole affinities, wherein 1, 19, 21–25, 27–28, and 32 bound more strongly than azide fragment 2 while anti-triazoles 20, 26, 29–31 were weaker binders than 2 (Table 2, Figure S1).

Table 2.

Rank-ordering of anti-triazoles 1, 19–32 and azide fragment 2 by dissociation constants (Kd) for 70S E. coli ribosomes determined by fluorescence polarization, along with experimental ΔG values (kcal/mol) and calculated normalized Ligand Grid Free Energies (LGFEs, kcal/mol) from SILCS. LGFEs are calculated for the total molecule, side-chain, and macrolactone+desosamine (Macro+Des) components. The side-chain is defined as the four-carbon alkyl linker and functionalized triazole extending from N11. Predictive indices (PIs) are calculated for each type of LGFE.45

| Cmpd | Kd (nM) | ΔG (kcal/mol) | Total LGFE (kcal/mol) | Side-chain LGFE (kcal/mol) | Macro+Des LGFE (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOL (1) | 0.6 ± 0.1 | –12.54 | –49.67 | –16.20 | –35.38 |

| 32 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | –12.41 | –51.83 | –17.09 | –35.30 |

| 19 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | –12.24 | –48.72 | –14.01 | –35.33 |

| 25 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | –12.22 | –48.70 | –14.87 | –35.57 |

| 23 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | –12.13 | –52.16 | –17.19 | –34.27 |

| 24 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | –12.06 | –50.83 | –15.50 | –34.86 |

| 28 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | –12.02 | –47.80 | –14.27 | –35.83 |

| 21 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | –12.00 | –50.82 | –16.23 | –35.24 |

| 22 | 1.7 ± 0.2 | –11.94 | –52.61 | –17.81 | –35.08 |

| 27 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | –11.91 | –47.93 | –13.64 | –34.70 |

| Azide 2 | 2.1 ± 0.4 | –11.82 | –38.85 | –5.04 | –35.85 |

| 31 | 2.4 ± 0.2 | –11.74 | –49.49 | –5.15 | –34.80 |

| 30 | 2.5 ± 0.3 | –11.73 | –48.96 | –3.91 | –35.37 |

| 26 | 2.5 ± 0.2 | –11.72 | –49.18 | –15.39 | –34.93 |

| 20 | 3.5 ± 0.5 | –11.53 | –52.86 | –18.55 | –34.91 |

| 29 | 5.0 ± 0.4 | –11.32 | –52.90 | –18.10 | –34.81 |

| PI | N/A | N/A | –0.22 | –0.14 | 0.37 |

In order to rationalize the relatively narrow range of measured Kd values despite significant differences in the structures of the alkynes, we performed a computational analysis to understand the relative alkyne contributions to the binding affinities using the Site-Identification by Ligand Competitive Saturation (SILCS) approach.41-44 SILCS maps the free energy affinity pattern of macromolecules onto a grid and may be used to quantitatively estimate relative binding affinities of ligands, yielding ligand grid free energies (LGFE). Details of the SILCS calculation and LGFE analysis are presented in the supporting information. Notably, the LGFE scores represent an atom-based free energy approximation allowing estimation of the contributions of different regions of molecules to binding affinity. Presented in Table 2 along with the experimentally-determined Kd and ΔG values (ΔG=–RTlnKd) are the calculated LGFE scores for anti-triazoles 1, 19–32, and azide 2, including (1) the total LGFE score of each compound; (2) the LGFE contributions of the respective side-chains; and, (3) the LGFE contributions of macrolactone and desosamine (Macro+Des) components. Analysis of the ability of the three LGFE metrics to predict the relative order of binding was then undertaken by calculating the predictive indices (PIs), which measures how well molecular modeling calculations track the ordering of the experimental binding values (see supporting information for details). The index varies from −1 (wrong prediction) to 0 (random) to +1 (perfect prediction).45

As shown in Table 2, the total and side-chain LGFE scores were not predictive whereas the Macro+Des LGFE yielded a satisfactory level of predictability. While somewhat unexpected, these results suggest that the binding of the ligands is dominated by the macrolactone and desosamine moieties, which are common to all of the triazole compounds. This hypothesis is consistent with the similarities in Kd values, with the relative binding affinities being associated with the ability of the unique side-chains to alter the interactions of the macrocycle and desosamine moieties with rRNA, rather than the side-chains directly interacting with rRNA themselves. Further support is found in the relative binding of known ketolides in which the addition of a side-chain did not markedly increase efficacy. For example, clarithromycin—the precursor to telithromycin (4) and solithromycin (1)—has a Kd value of 1.7 nM despite the absence of a side-chain (see supporting information).11,13 The significance and utility of the side-chains in congeners 1 and 4 is demonstrated by bacterial ribosomes that acquire resistance from either mutation or modification, which render first-generation antibiotics erythromycin and clarithromycin ineffective due to markedly decreased binding affinity.13,46,47

Detailed analysis revealed several important structure-activity relationships within the library. Specifically, meta- or 3-substituted aromatic and/or heteroaromatic groups with the ability to engage in hydrogen bonding provided the best boost in affinity relative to the azide alone (e.g., 1,19, 21–22, 25). In contrast, the 3-substituted trifloromethylphenyl, and 2-fluorophenyl triazoles, 20 and 26, respectively, with no capacity for hydrogen bonding, failed to enhance affinity. In addition, the nonaromatic triazoles 29, 30, and 31 all showed decreased binding as compared to 2, indicating that moieties that participate primarily in hydrogen bond interactions but cannot participate in π-stacking do not stabilize macrocycle+desosamine–rRNA interactions. These results suggest that the ability of the side-chain to participate in both π-stacking and hydrogen bonding leads to stabilization of macrolactone+desosamine–rRNA interactions. We attribute the relatively high binding activity of the nonaromatic morpholine-containing triazole 32, which bound only slightly less tightly than solithromycin (1, SOL), to the presence of a basic amine that can interact electrostatically with rRNA. Lastly, the five-membered heteroaromatics 27–28 showed increased binding and thus represent an interesting, novel class to explore.

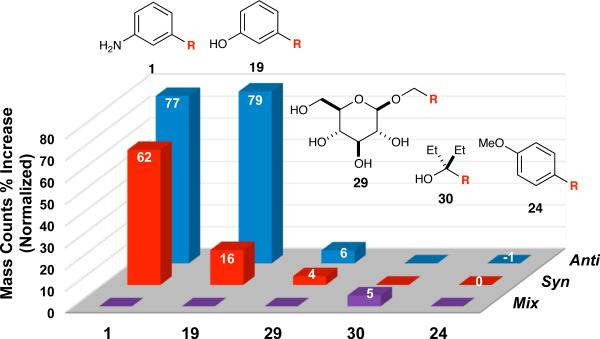

Guided by the Kd values, two in situ click experiments were designed wherein azide 2 was incubated with five different alkynes in the presence of 50S E. coli ribosomal subunits to test whether the target could differentiate between triazoles with Kd values lower than azide 2 and those with higher Kd values. The first experiment included 3-ethynylaniline (3), which is the precursor to solithromycin (1), along with 5, 10, 15, and 16 (2 mM each; 10 mM total), 10 μM azide 2, and 10 μM 50S E. coli ribosomal subunits at rt for 48 h. Azide and ribosomal subunit concentrations were doubled relative to the binary experiment to ensure sufficient product formation under competitive reaction conditions. The results (Figure 3) show that 1 provides the greatest combined mass counts, with the anti-regioisomer (solithromycin, 1) being preferred over syn-1. Phenol-functionalized triazole 19, which possessed a low Kd for the anti-regioisomer, was also formed in significant amounts. This fact establishes the importance of aromatic fragments with the capacity for hydrogen bonding with rRNA at the meta-position, again drawing an analogy to 1. Triazole formation from glucosyl alkyne 15 resulted in small amounts of both syn- and anti-29. Aliphatic compound 30 was not formed in significant amounts, which we attribute to the absence of π-stacking interactions. Interestingly, triazole 24 was formed in the lowest amount, even though it is capable of π-stacking and has a Kd lower than that of azide 2. We posit this phenomenon is most likely due to competitive product inhibition arising from 1 and 19, which are two of the tightest binders in the library.14,21

Figure 3.

In situ click experiment with azide 2 and alkynes 3, 5, 10, 15, and 16, yielding triazoles 1, 19, 24, 29, and 30, respectively. Mix represents unresolved anti- and syn-isomers. Normalized mass count percent increases (provided in the bars) are calculated from the ratio of the ribosometemplated reaction to the background reaction. Results are an average of two experiments. The remainder of the molecule is abbreviated as ‘R’.

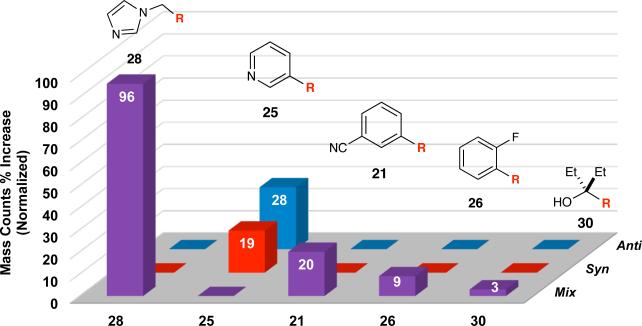

The second, five-alkyne in situ click experiment featured alkynes bearing a range of functional groups such as alcohol 16, imidazole 14, pyridine 11, nitrile 7, and fluoride 12, selected to determine how the ribosome-templated reaction would perform in the presence of alkynes that yield triazoles binding more weakly than 1. The results from the experiment are shown in Figure 4. Imidazole-functionalized triazole 28, as a mixture of syn- and anti-regioisomers, was detected in the greatest amount, consistent with the low Kd value for the anti-isomer, followed by 25 then 21. In contrast, triazoles 26 and 30 were not detected in significant quantities. Taken together, the two five-alkyne in situ click experiments demonstrate that the ribosome can template the formation of tighter-binding triazoles in greater quantity.

Figure 4.

In situ click experiment with azide 2 and alkynes 7, 11–12, 14, and 16 yielding triazoles 21, 25–26, 28, and 30, respectively. Mix represents unresolved anti- and syn-isomers. Normalized mass count percent increases (provided in the bars) are calculated from the ratio of the ribosometemplated reaction to the background reaction. Results are an average of two experiments. The remainder of the molecule is abbreviated as ‘R’.

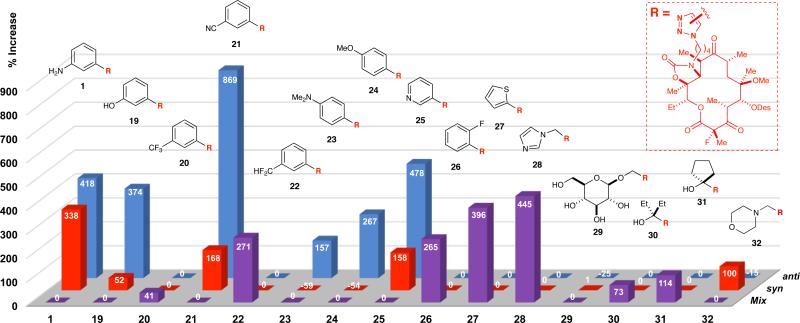

The successful execution of five-alkyne in situ click experiments justified a greater exploration of chemical space while expanding the scope of the method. To this end, we initiated experiments with fifteen alkynes, which would yield thirty congeners (Figure 5). These included alkynes from the two five-alkyne experiments, along with six additional alkynes (i.e., 6, 8–9, 13, 17–18). To ensure complete alkyne solubilization, the concentration of each member was decreased from 2 mM to 1 mM, and the concentrations of azide 2 and 70S E. coli ribosomes were maintained at 10 μM each. The fifteen-component alkyne mixture (15 mM total) was sonicated for 1–5 min to obtain a homogenous solution, prior to the addition of azide 2 and ribosomes, and the reaction mixture was incubated at rt for 48 h. Consistent with the five-alkyne in situ click reactions, we detected the formation of triazoles with Kd values lower than 2 (i.e., better binders than the azide fragment) including solithromycin (1), 19, 21–25, 27, and 28 (Figure 5). All of these cycloadducts were derived from aromatic alkynes, again underscoring the significance of π-stacking interactions with the A752-U2609 base pair. The only aromatic triazole that was not detected in appreciable quantity was trifluoromethyl congener 20. However, its Kd value (Table 2) was the second highest of the library, further illustrating selectivity in the in situ click process. Non-aromatic triazoles 29, 30, and 31 were not detected in significant quantities. In addition, morpholine-functionalized 32 was not detected in significant quantities, despite the fact that it binds ribosomes as well as 1. We attribute this observation to the basicity of N-propargyl morpholine (18), which, though its pKa is 5.55,48 could be protonated when bound to the ribosome due to electrostatic interactions with phosphate residues. Such binding could effectively sequester this fragment and preclude coupling with 2. Competitive product inhibition, which was observed in both five-alkyne competition experiments (vide supra), may account for the modest formation of triazoles 20, 29–32.

Figure 5.

In situ click experiment with azide 2 and alkynes 3, 5–18 yielding triazoles 1 and 19–32, respectively. Mix represents an unresolved mixture of anti- and syn-isomers. Mass count percent increases (provided in the bars) are calculated from the ratio of the ribosome-templated reaction to the background reaction. Results are an average of five experiments.

Curiously, the ribosome-templated synthesis of solithromycin (1) gave slightly different syn/anti ratios for the binary reaction (~2:1) versus the five- and fifteen-alkyne competition experiments, the latter two of which gave similar syn/anti ratios (~1.24/1). We also observed this reaction-dependent change in regioisomer ratios with phenol 19 and pyridine 25. The isolation of nitrile 21 as a ‘mix’ in Figure 4 and subsequent resolution thereof [i.e., ~5:1 (anti/syn)] in Figure 5 is attributed to chromatographic issues and not the reaction per se.49 The modulation of regioisomer ratios illustrates the complex nature of in situ click competition experiments wherein the alkyne mixtures, which are in mM concentrations, are likely modifying the architecture of the macrolide-binding site via direct or allosteric interactions with rRNA. Finally, the marked and reproducible ribosome-templated formation of nitrile 21 in the fifteen-alkyne (Figure 5) vis-à-vis the five-alkyne experiment (Figure 4) is striking. This result is difficult to rationalize in terms of Kd or LGFE and may arise from the complexity of the reaction mixture. To probe this, we are currently investigating ten-alkyne mixtures that are more consistent with the prior art.20-25

We next assessed the mechanism of action of azide 2 and anti-triazoles 1, 19–32 and evaluated their antibiotic activities using (1) in vitro protein synthesis assays using a cell-free system50 and (2) minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) assays for azide 2, anti-triazoles 1, and 19–32 (Table 3).51 As the ribosome-templated in situ click process delivers bivalent inhibitors possessing greater potency than their monovalent components, it is important to determine the selectivity of the newly formed cycloadducts for bacterial versus mammalian ribosomes. To this end, we evaluated anti-triazoles 1 (solithromycin), azide 2, and four analogs from our library using a mammalian cell toxicity assay with human fibroblasts.

Table 3.

Evaluation of azide 2, anti-triazoles 1 (SOL) and 19–32 using minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) assays (μg/mL) against E. coli and S. pneumoniae strains. Compounds are rank-ordered by potency in MIC assays against E. coli then S. pneumoniae strains. MIC values determined in three independent experiments; translation values in two independent experiments. Analysis of the data in Table 3 reveals that the poorest-performing compounds (32, 20, and 29, shown in red) against both strains correlate with the binding data; in fact, 20 and 29 had the highest Kd values. The polarity of 29 and 32 may be contributing to poor uptake and/or permeability. Predictive indices (PIs) are calculated for the MICs against each strain with respect to Kd values.

| Cmpd | Kd (nM) | ΔG (kcal/mol) | MIC E. coli DK pKK 3535 | MIC E. coli DK A2058G | MIC S. pneumo ATCC 49619 | MIC S. pneumo 655 mefA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 27 | 1.8 | −11.9 | 1 | 1 | 0.004 | 0.5 |

| 19 | 1.1 | −12.2 | 2 | 1 | 0.002 | 0.5 |

| 28 | 1.5 | −12.0 | 2 | 2 | 0.032 | 4 |

| SOL (1) | 0.6 | −12.6 | 2 | 2 | 0.006 | 0.375 |

| Azide 2 | 2.1 | −11.8 | 2 | 2 | 0.002 | 0.25 |

| 24 | 1.4 | −12.1 | 2 | 2 | 0.005 | 1 |

| 26 | 2.5 | −11.7 | 2 | 2 | 0.002 | 0.5 |

| 25 | 1.1 | −12.2 | 2 | 2 | 0.016 | 0.5 |

| 22 | 1.7 | −12.0 | 2 | 4 | 0.004 | 1 |

| 23 | 1.3 | −12.1 | 4 | 4 | 0.008 | 1 |

| 21 | 1.6 | −12.0 | 4 | 4 | 0.016 | 1 |

| 31 | 2.4 | −11.7 | 4 | 4 | 0.016 | 2 |

| 30 | 2.5 | −11.7 | 4 | 4 | 0.032 | 2 |

| 20 | 3.5 | −11.5 | 4 | 4 | 0.016 | 2 |

| 32 | 0.8 | −12.4 | 8 | 8 | 0.063 | 4 |

| 29 | 5 | −11.3 | 32 | 32 | 4 | 4 |

| PI | N/A | N/A | 0.46 | 0.48 | 0.34 | 0.44 |

For the in vitro translation inhibition studies, all of the compounds were assayed at 1 μM. Given that the 70S concentration in the cell-free protein synthesis (CFPS) reactions are 1.5 ± 0.2 μM (RTS100 kit, 5PRIME)50 and 1.4 ± 0.1 μM (Expressway Mini kit, Invitrogen, see supporting information), we would expect these low- to sub- nM affinity compounds to bind 70S stoichiometrically, negating any differences in affinity and yielding an expected inhibition of approximately 70 ± 10%. Indeed, all of the compounds, including the azide, inhibited the CFPS reaction in the range of 48 ± 16% (see supporting information). This inhibition is toward the lower end of the predicted range, which may be due to inhibitor sequestration by other components in these heterogeneous lysate-based mixtures, reducing the effective inhibitor concentration. Differential sequestration between compounds could also explain the variation observed between the best inhibitor (32, 64 ± 14% inhibition) and the worst inhibitor (29, 32 ± 5% inhibition).

For the MIC assays, we tested solithromycin (1, SOL), azide 2, and anti-triazoles 19–32 against various strains of E. coli, S. pneumoniae, and S. aureus.52 Strains ATCC 29213 (S. aureus) and ATCC 49619 (S. pneumoniae) served as quality control strains with values for SOL (1), giving results closely matching published values.51 The results in Table 3 show that thiophene-functionalized triazole 27 was two-fold more potent than SOL against E. coli DK pkk3535 strain and A2058G strains and that the relatively high affinity (low Kd) phenolfunctionalized triazole 19 was two-fold more potent than SOL in the S. pneumoniae ATCC wild-type and E. coli mutant DK A2058G strains.53 Comprehensive structure-activity relationship studies of these two analogs could result in the discovery of novel, potent antibiotics. In addition, three of the poorest-performing compounds against both S. pneumoniae strains (20, 29, 30 shown in red) include two, 20 and 29, having the highest Kd values. Consistent with this are the Predictive indices (PIs) of the Kd values in Table 3 for the MIC values, indicating affinity to be a reasonable predictor of functional activity.45 However, adduct 32 (also shown in red) is less potent than would be expected from its Kd value, which could indicate an uptake problem. Taken together, these results indicate satisfactory levels of selectivity in the ribosome-templated in situ click process. It is important to note that while solithromycin (1) and the library of analogs prepared herein maintained their efficacy against resistant E. coli and S. pneumoniae strains (Table 3), this was not the case for all resistant strains tested (see Tables S5 and S6, supporting information).

For the cell viability assays, the potential cytotoxicity of solithromycin (1), azide (2), and analogs 19, 24, 27, and 28 against human dermal fibroblasts (GM05659, Coriell Institute, Camden, NJ)54 was measured using a commercial luciferase-coupled ATP quantitation assay (CellTiter-Glo®, Promega).55 The cells were incubated with test compounds at concentrations ranging from 50 μM to 0.88 nM for 24- and 48-hour time periods (see Figures S3–S5, supporting information). Significantly, the data showed that, like 1, compounds 24, and 27–28 showed no effect on fibroblasts after 24 or 48 hours up to low micromolar concentrations. The therapeutic indices for these compounds (i.e., bactericidal activity versus mammalian cytotoxicity) were essentially the same as that measured for solithromycin (1).

CONCLUSION

We have developed an in situ click chemistry method that employs 70S E. coli ribosomes and 50S ribosomal subunits as platforms, with the ribosome-templated synthesis of solithromycin (1) serving as proof-of-concept. The method was applied in five- and fifteen-alkyne competition experiments. Consistent with other kinetic, target-guided in situ click processes, the extent of triazole formation correlated with ribosome binding affinity (see Chart S1, supporting information). The 50S E. coli ribosomal subunit was also studied using the computational Site-Identification by Ligand Competitive Saturation (SILCS) approach. Interestingly, LGFEs associated with the macrolactone and desosamine moieties, rather than the full triazole structures, were correlated to dissociation constants for the congeners, suggesting that the side-chain indirectly impacts affinity by altering macrocycle–ribosome interaction.

The inclusion of bacterial ribosomes in the repertoire of targets represents a powerful drug discovery platform that obviates the onerous need to independently synthesize, characterize, and evaluate both syn- and anti-triazoles. Significantly, the use of ribosomes possessing known mechanisms of resistance (e.g., rRNA modification or mutation) can lead to the discovery of antibiotics that selectively target resistant over wild-type bacterial strains. Protein synthesis inhibition experiments confirmed the mechanism of action of these congeners. MIC evaluation of the in situ click products quantified antibiotic activity and firmly established this method as efficacious in the triaging and prioritization of potent antibiotic candidates targeting the bacterial ribosome. Finally, we showed that four analogs discovered using ribosome-templated in situ click chemistry (i.e., 19, 24, 27, 28) displayed similar therapeutic indices as that seen with solithromycin (1).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the NIH (AI080968, GM070855 and GM051501), the University of Maryland Computer-Aided Drug Design Center, and Temple University. We thank Prof. Paul Edelstein (Penn Medicine) for kindly providing us with wild-type and resistant S. pneumoniae strains. We thank Dr. Charles DeBrosse, Director of the NMR Facility at Temple Chemistry, for kind assistance with NMR experiments. Finally, we thank Dr. Charles W. Ross III for assistance with LC/MS experiments and for carefully reading this manuscript.

Footnotes

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): A.D.M. is cofounder and CSO of SilcsBio LLC.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information. General and in situ click methods and data, computational methods, determination of Kd by fluorescence polarization with BODIPY-labeled erythromycin, cell-free translation inhibition method and data, minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) method and data, mammalian cell toxicity assay, synthetic methods including synthesis and full structural assignment of azide 2, Cu(I)-catalyzed click synthesis and characterization of anti-triazoles 1, 19–32. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Walsh C. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2003;1:65. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levy SB, Marshall B. Nature Medicine. 2004;10:S122. doi: 10.1038/nm1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Solomon SL, Oliver KB. Am. Fam. Physician. 2014;89:938. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bush K, Courvalin P, Dantas G, Davies J, Eisenstein B, Huovinen P, Jacoby GA, Kishony R, Kreiswirth BN, Kutter E, Lerner SA, Levy S, Lewis K, Lomovskaya O, Miller JH, Mobashery S, Piddock LJV, Projan S, Thomas CM, Tomasz A, Tulkens PM, Walsh TR, Watson JD, Witkowski J, Witte W, Wright G, Yeh P, Zgurskaya HI. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011;9:894. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fox JL. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006;24:1521. doi: 10.1038/nbt1206-1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wright PM, Seiple IB, Myers AG. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:8840. doi: 10.1002/anie.201310843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K. Journal of Molecular Graphics & Modelling. 1996;14:33. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernandes P, Pereira D, Jamieson B, Keedy K. Drug Future. 2011;36:751. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bryskier A. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2000;6:661. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0691.2000.00185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tenson T, Mankin A. Mol. Microbiol. 2006;59:1664. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yan K, Hunt E, Berge J, May E, Copeland RA, Gontarek RR. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005;49:3367. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.8.3367-3372.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spahn CMT, Prescott CD. J. Mol. Med. 1996;74:423. doi: 10.1007/BF00217518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Llano-Sotelo B, Dunkle J, Klepacki D, Zhang W, Fernandes P, Cate JHD, Mankin AS. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010;54:4961. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00860-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jencks WP. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1981;78:4046. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.7.4046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mamidyala SK, Finn MG. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010;39:1252. doi: 10.1039/b901969n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rostovtsev VV, Green LG, Fokin VV, Sharpless KB. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002;41:2596. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020715)41:14<2596::AID-ANIE2596>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boren BC, Narayan S, Rasmussen LK, Zhang L, Zhao HT, Lin ZY, Jia GC, Fokin VV. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:8923. doi: 10.1021/ja0749993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rees DC, Congreve M, Murray CW, Carr R. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2004;3:660. doi: 10.1038/nrd1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scott DE, Coyne AG, Hudson SA, Abell C. Biochemistry. 2012;51:4990. doi: 10.1021/bi3005126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manetsch R, Krasinski A, Radic Z, Raushel J, Taylor P, Sharpless KB, Kolb HC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:12809. doi: 10.1021/ja046382g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lewis WG, Green LG, Grynszpan F, Radic Z, Carlier PR, Taylor P, Finn MG, Sharpless KB. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002;41:1053. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020315)41:6<1053::aid-anie1053>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krasiński A, Radić Z, Manetsch R, Raushel J, Taylor P, Sharpless KB, Kolb HC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:6686. doi: 10.1021/ja043031t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grimster NP, Stump B, Fotsing JR, Weide T, Talley TT, Yamauchi JG, Nemecz A, Kim C, Ho KY, Sharpless KB, Taylor P, Fokin VV. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:6732. doi: 10.1021/ja3001858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mocharla VP, Colasson B, Lee LV, Roper S, Sharpless KB, Wong CH, Kolb HC. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;44:116. doi: 10.1002/anie.200461580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Whiting M, Muldoon J, Lin YC, Silverman SM, Lindstrom W, Olson AJ, Kolb HC, Finn MG, Sharpless KB, Elder JH, Fokin VV. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;45:1435. doi: 10.1002/anie.200502161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hirose T, Sunazuka T, Sugawara A, Endo A, Iguchi K, Yamamoto T, Ui H, Shiomi K, Watanabe T, Sharpless KB, Omura SJ. Antibiot. 2009;62:277. doi: 10.1038/ja.2009.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Namelikonda NK, Manetsch R. Chem. Commun. 2012;48:1526. doi: 10.1039/c1cc14724b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poulin-Kerstien AT, Dervan PB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:15811. doi: 10.1021/ja030494a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sharpless KB, Manetsch R. Expert Opinion on Drug Discovery. 2006;1:525. doi: 10.1517/17460441.1.6.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Willand N, Desroses M, Toto P, Dirié B, Lens Z, Villeret V, Rucktooa P, Locht C, Baulard A, Deprez B. ACS Chemical Biology. 2010;5:1007. doi: 10.1021/cb100177g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rzuczek SG, Park H, Disney MD. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:10956. doi: 10.1002/anie.201406465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Millward SW, Henning RK, Kwong GA, Pitram S, Agnew HD, Deyle KM, Nag A, Hein J, Lee SS, Lim J, Pfeilsticker JA, Sharpless KB, Heath JR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:18280. doi: 10.1021/ja2064389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Agnew HD, Rohde RD, Millward SW, Nag A, Yeo WS, Hein JE, Pitram SM, Tariq AA, Burns VM, Krom RJ, Fokin VV, Sharpless KB, Heath JR. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:4944. doi: 10.1002/anie.200900488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pfeilsticker JA, Umeda A, Farrow B, Hsueh CL, Deyle KM, Kim JT, Lai BT, Heath JR. Plos One. 2013:8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nag A, Das S, Yu MB, Deyle KM, Millward SW, Heath JR. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:13975. doi: 10.1002/anie.201305882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Farrow B, Hong SA, Romero EC, Lai B, Coppock MB, Deyle KM, Finch AS, Stratis-Cullum DN, Agnew HD, Yang S, Heath JR. Acs Nano. 2013;7:9452. doi: 10.1021/nn404296k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Deyle KM, Farrow B, Hee YQ, Work J, Wong M, Lai B, Umeda A, Millward SW, Nag A, Das S, Heath JR. Nature Chemistry. 2015;7:455. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liang CH, Yao SL, Chiu YH, Leung PY, Robert N, Seddon J, Sears P, Hwang CK, Ichikawa Y, Romero A. Biorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2005;15:1307. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grigoriadou C, Marzi S, Kirillov S, Gualerzi CO, Cooperman BS. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;373:562. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kolb HC, Finn MG, Sharpless KB. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2001;40:2004. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010601)40:11<2004::AID-ANIE2004>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Raman EP, Yu W, Lakkaraju SK, MacKerell AD., Jr. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2013;53:3384. doi: 10.1021/ci4005628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Raman EP, Yu W, Guvench O, Mackerell AD. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2011;51:877. doi: 10.1021/ci100462t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guvench O, MacKerell Jr AD. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2009;5:e1000435. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lakkaraju SK, Yu W, Raman EP, Hershfeld AV, Fang L, Deshpande DA, MacKerell AD., Jr. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2015;55:700. doi: 10.1021/ci500729k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pearlman DA, Charifson PS. J. Med. Chem. 2001;44:3417. doi: 10.1021/jm0100279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mankin AS. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2008;11:414. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dunkle JA, Xiong L, Mankin AS, Cate JHD. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010;107:17152. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007988107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Williams A, Jencks WP. J. Chem. Soc.-Perkin Trans. 2. 1974:1760. [Google Scholar]

- 49.The change in chromatographic separation of syn/anti regioisomers is a result of the reverse-phase HPLC columns, whose resolution deteriorate with multiple passage of bacterial ribosomes or ribosomal subunits. We are working to ameliorate this issue.

- 50.Rosenblum G, Chen C, Kaur J, Cui X, Goldman YE, Cooperman BS. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:e88. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reller LB, Weinstein M, Jorgensen JH, Ferraro MJ. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009;49:1749. doi: 10.1086/647952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.See supporting information for MIC evaluation against a broader panel of wild-type and resistant strains of E. coli, S. pneumoniae, and S. aureus.

- 53.DK/pKK3535 refer to a tolC(−) strain with wild-type (WT) ribosomes. DK/A2058G refer to a tolC(−) strain with a mixed population of WT and mutant ribosomes (ca. 1:1) wherein Adenine has mutated to Guanine, which represents a clinically signifcant mechanism of resistance. TolC is an outermembrane efflux pump that recognizes antibiotics (e.g., macrolides), thus making these tolC(−) E. coli DK strains useful (and relevant) models of pathogenic gram positive bacteria. Moreover, the ribosomes employed in this study are derived from E. coli.

- 54. https://catalog.coriell.org/0/Sections/Search/Sample_Detail.aspx?Ref=GM05659.

- 55. https://www.promega.com/products/cell-health-and-metabolism/cell-viability-assays/celltiter_glo-luminescent-cell-viability-assay/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.