Abstract

Background

Clinically distinct autoimmune phenotypes share genetic susceptibility factors. We investigated the prevalence of familial autoimmunity among subjects with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), childhood systemic lupus erythematosus (cSLE) and juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM) in the CARRA Registry, the largest multicenter observational Registry for pediatric rheumatic disease.

Methods

Children with JIA, cSLE and JDM enrolled in the CARRA Registry between May 2010 and May 2012 were investigated for differences in proportion of subjects who had first-degree relatives (FDR) with autoimmunity. If a significant difference was detected, pairwise comparisons, adjusted for multiple comparisons, were made.

Results

There were 4677 JIA, 639 cSLE and 440 JDM subjects. The proportion of subjects having FDR with any autoimmune disease in the JDM group (20.5 %) was less compared to subjects with JIA (31.8 %, p < 0.001) or SLE (31.9 %; p < 0.001). Significantly greater proportion of JIA cases had FDR with inflammatory arthritis (13 %) compared to cSLE (9.2 %, p = 0.007) or JDM (4.3 %, p <0.001). Significantly greater proportion of cSLE cases had FDR with SLE (11.1 % vs. 1.7 % for JIA and 1.1 % for JDM p < 0.001) or type-I diabetes (7.4 % for cSLE vs. 3.1 % for JIA and 3.0 % for JDM p < 0.001).

Conclusion

Higher proportions of subjects with JIA and cSLE have FDR with autoimmunity compared to those of JDM. Relatives of cSLE cases had an increased prevalence of SLE, and relatives of JIA cases were enriched for inflammatory arthropathies demonstrating distinct patterns of familial autoimmunity among these phenotypes.

Background

Autoimmune disorders are relatively common, estimated to affect 5 to 10 % of the population. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), childhood onset systemic lupus erythematosus (cSLE) and juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM) are examples of autoimmune disorders affecting the pediatric population. Although autoimmune disorders are clinically distinct phenotypes, there is substantial evidence to suggest that they may share common genetic susceptibility factors. Variants in PTPN22 and STAT4 genes exemplify genetic variants associated with multiple autoimmune phenotypes [1–4].

There is also clinical evidence for the clustering of autoimmunity in individuals and families [5, 6]. For instance, children with JIA have increased prevalence of autoimmune thyroiditis and type 1 diabetes [7, 8]. Relatives of children with JIA,, cSLE and JDM have a higher prevalence of autoimmunity [9–11]. In some instances, two autoimmune phenotypes show inverse relationships. While RA, autoimmune thyroiditis and type 1 diabetes were comorbid more often than expected, there was reduced comorbidity of multiple sclerosis and RA [6]. Our objective was to investigate the prevalence of familial autoimmunity among subjects with JIA, cSLE and JDM in the CARRA Registry, the largest multicenter observational Registry for pediatric rheumatic disease. We sought to explore if there were distinct patterns of familial clustering of autoimmune diseases among these phenotypes

Subjects and methods

Children with JIA, cSLE and JDM from pediatric rheumatology clinics in the US were enrolled in the CARRA Registry between May 2010 and May 2012. Demographic and disease-related data were collected from time of diagnosis to enrollment visit as previously described [12–14]. Demographic variables including gender, race and ethnicity, as well as quality of life measures were collected by self-report by patients and/or parents via a questionnaire. Family history information included the presence of an autoimmune disease in any first degree relative of the proband. Specifically the following disorders was queried: SLE, psoriasis, Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis, ankylosing spondylitis/spondyloarthropathy, acute anterior uveitis, JIA, RA, multiple sclerosis, autoimmune thyroiditis, celiac disease, and type 1 diabetes. In addition, an “other autoimmune disorders” category was included. ANA status, age at onset of disease, age at diagnosis and age at enrollment were available by chart review. Institutional Review Board approval was given for this study by Emory University. CARRA sites also had local IRB approval to provide data to the CARRA Registry.

Statistical methods

All statistical analyses were conducting using SAS 9.3 (Cary, NC). Statistical significance was assessed at 0.05 unless otherwise noted. Demographic and disease characteristics are summarized using means and standard deviations or counts and frequencies for each autoimmune disorder (subgroup), as appropriate. Demographic characteristics were compared among the three groups using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) models for continuous data and Chi-square tests for categorical data. For each autoimmune disorder (JIA, cSLE, and JDM), we calculated the proportion of children that had a first-degree relative with any type of autoimmunity. To determine if subjects with JIA, cSLE, or JDM had a different proportion of first-degree relatives with autoimmunity, we performed Chi-square tests or Fisher Exact tests if the frequencies were small (n < 5). When a significant difference was detected, post-hoc pairwise comparisons, adjusted for multiple comparisons, were made among the three groups to determine which groups significantly differed using a significance level of 0.05/3 = 0.017. Additionally, Chi-square tests were used to compare the proportion of children within JIA categories [15] (systemic, rheumatoid factor (RF)-negative polyarticular JIA, RF-positive polyarticular JIA, persistent oligoarticular JIA, extended oligoarticular JIA, psoriatic JIA, ERA, and undifferentiated JIA) that had a first-degree relative with autoimmunity. While we investigated if overall differences in the prevalence of familial autoimmunity existed between the different categories of JIA, we were not powered to perform pairwise comparisons between sets of JIA categories. Finally, the total number of familial autoimmune diseases was tabulated for each patient. The Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance was used to determine if number of familial autoimmune diseases significantly differed by disease group. Additionally, the number of familial autoimmune diseases was categorized into the following categories: 0, 1–2, 3 or more and compared among the three disease groups.

Results

Patient characteristics

The sample consisted of 5756 patients with JIA (n = 4677), cSLE (n = 639) or JDM (n = 440) from the CARRA registry. The majority of the patients were classified as having JIA (81.3 %), being female (73.3 %) and Caucasian (85.3 %). The average age of patients in the dataset at enrollment was 11.9 years (±4.8) and the average age at onset of symptoms was 7.1 years (±4.7). Table 1 provides a summary of patient demographics for the entire sample and broken down by disease group (JIA, cSLE and JDM). Patients with a diagnosis of JDM or JIA were younger than patients with a diagnosis of cSLE (JDM: 11.9 ± 4.4 years; JIA: 11.0 ± 4.4; cSLE: 16.0 ± 3.2 years; p < 0.001) and had a younger-age at onset of symptoms (p < 0.001). Additionally, cSLE patients were more likely to be female and African-American or Asian compared to patients with JIA or JDM. Other differences were found between groups related to quality of life measures and ANA positivity.

Table 1.

Comparison demographics groups among disease groups

| Characteristic | Total | JIA | SLE | JDM | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number | 5,756 | 4,677 | 639 | 440 | |

| Female gender N (%) | 4,218 (73.3) | 3,368 (79.9) | 532 (83.4) | 318 (72.3) | <0.001 |

| Age at enrollment (years) | 11.9 ± 4.8 | 11.4 ± 4.8 | 16.0 ± 3.2 | 11.0 ± 4.4 | <0.001 |

| Age onset of symptoms (years) | 7.1 ± 4.7 | 6.5 ± 4.5 | 12.3 ± 3.2 | 6.6 ± 3.8 | <0.001 |

| Race N (%) | |||||

| AA a | 551 (9.6) | 269 (5.8) | 225 (35.2) | 57 (13.0) | <0.001 |

| AI b | 95 (1.7) | 73 (1.6) | 12 (1.9) | 10 (2.3) | 0.476 |

| Asian | 197 (3.4) | 116 (2.5) | 69 (10.8) | 12 (2.7) | <0.001 |

| NH c | 36 (0.6) | 25 (0.5) | 8 (1.3) | 3 (0.7) | 0.096 |

| White | 4,912 (85.3) | 4,244 (90.7) | 307 (48.0) | 361 (82.1) | <0.001 |

| Other | 222 (3.9) | 146 (3.1) | 51 (8.0) | 25 (5.7) | <0.001 |

| Ethnicity (Non-Hispanic) N (%) | 5,059 (87.9) | 4,214 (90.1) | 464 (72.6) | 381 (86.6) | <0.001 |

| Overall Well-being Score | 2.3 ± 2.3 | 2.3 ± 2.3 | 2.6 ± 2.5 | 2.1 ± 2.3 | <0.001 |

| PGA | 1.6 ± 1.9 | 1.6 ± 1.9 | 2.0 ± 1.9 | 1.6 ± 1.9 | <0.001 |

| CHAQ | 0.34 ± 0.51 | 0.35 ± 0.51 | 0.24 ± 0.46 | 0.36 ± 0.63 | <0.001 |

| ANA N (% positive)d | 2,802 (56.2) | 2,012 (49.7) | 577 (96.5) | 213 (62.3) | <0.001 |

aAA – African American or Black, bAI- American Indian or Alaskan Native

cNH- Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, dIndicates missing data

Family history of autoimmune disease

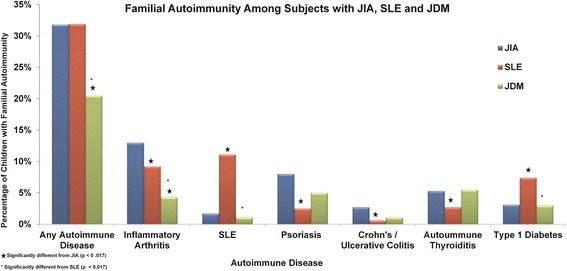

We compared the proportion of children with first-degree relatives with various autoimmune diseases among the three diagnosis groups (Fig. 1 and Table 2). The proportion of patients having first degree relatives with any autoimmune disease in the JDM group (20.5 %) was significantly less compared to patients with JIA (31.8 %, p < 0.001) and patients with cSLE (31.9 %; p < 0.001). There were no statistically significant differences in the proportion of JIA, cSLE and JDM patients with first degree relatives that had autoimmune thyroiditis, multiple sclerosis, acute anterior uveitis or other autoimmune disorders.

Fig. 1.

Familial autoimmunity among subjects with JIA, cSLE and JDM. Proportion of cases with JIA, cSLE and JDM that report having first degree relatives with various autoimmune disorders. Asterisks denote differences that are statistically significant after correction for multiple testing

Table 2.

Comparison of cases with JIA, cSLE and JDM with autoimmune disorders among first-degree relatives

| Family history of disease | Disease group | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| JIA | cSLE | JDM | ||

| (N = 4,677) | (N = 639) | (N = 440) | ||

| Any autoimmune disease | 1,488 (31.8) | 204 (31.9) | 90 (20.5)a b | <0.001 |

| Inflammatory Arthritis -(AS, Spondyloarthropathy, JIA, RA) | 608 (13.0) | 59 (9.2)a | 19 (4.3)a b | <0.001 |

| Ankylosing spondylitis | 61 (1.3) | 1 (0.2)a | 2 (0.5) | 0.014 |

| Spondyloarthropathy | 36 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.015 |

| JIA | 241 (5.2) | 14 (2.2)a | 4 (0.9)a | <0.001 |

| RA | 340 (7.3) | 50 (7.8) | 15 (3.4)a b | 0.007 |

| Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis | 126 (2.7) | 4 (0.6)a | 5 (1.1) | 0.002 |

| Acute anterior uveitis | 15 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.169 |

| Psoriasis | 372 (8.0) | 16 (2.5)a | 22 (5.0) | <0.001 |

| SLE | 77 (1.7) | 71 (11.1)a | 5 (1.1)b | <0.001 |

| Multiple Sclerosis | 45 (1.0) | 7 (1.1) | 5 (1.1) | 0.905 |

| Autoimmune thyroiditis | 248 (5.3) | 17 (2.7)a | 24 (5.5) | 0.015 |

| Celiac | 36 (0.8) | 5 (0.8) | 6 (1.4) | 0.439 |

| Type 1 Diabetes | 147 (3.1) | 47 (7.4)a | 13 (3.0)b | <0.001 |

| Other autoimmune | 214 (4.6) | 32 (5.0) | 20 (4.6) | 0.893 |

All values are N (%)

aSignificantly different from JIA (p < 0.017)

bSignificantly different from SLE (p < 0.017)

JIA versus cSLE

Compared to subjects with cSLE, a significantly greater proportion of patients with JIA had first-degree relatives with any inflammatory arthritis (p = 0.007), ankylosing spondylitis (p = 0.016), JIA (p = 0.001), psoriasis (p < 0.001), Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis (p = 0.002), and autoimmune thyroiditis (p = 0.005). In contrast, compared to JIA, a significantly higher proportion of patients with cSLE had first-degree relatives with SLE (p < 0.001) and type-I diabetes (p < 0.001). A similar proportion of cases with JIA and cSLE had FDR with RA (7.3 % vs 7.8 %, p = ns).

JIA versus JDM

Compared to patients with JDM, a significantly greater proportion of patients with JIA had first-degree relatives with JIA (p < 0.001), RA (p = 0.002), and any inflammatory arthritis (p < 0.001) (Table 2).

cSLE versus JDM

Compared to patients with JDM, a significantly higher proportion of patients with cSLE had first-degree relatives with any inflammatory arthritis (p = 0.003), RA (p = 0.003), SLE (p < 0.001), and type-1 diabetes (p < 0.001) (Fig. 1 and Table 2).

We also calculated the mean and median number of familial autoimmune diseases a child had for each diagnosis group (Table 3). Overall, there was a difference in the distribution of the number of familial autoimmune diseases with JDM having significantly fewer familial diseases compared to JIA (p < 0.001) and cSLE (p < 0.001). In addition, after classifying the number of familial diseases into 0, 1–2, and 3 or more, we showed that children with JIA or cSLE were more likely to have at least 1 familial autoimmune disease reported compared to children with JDM (p < 0.001).

Table 3.

Comparison of the number of autoimmune disease (family history) among disease groups

| Outcome | Level | Disease group | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JIA | SLE | JDM | |||

| (N = 4,677) | (N = 639) | (N = 440) | |||

| # of autoimmune diseases in family | |||||

| Mean ± SD | -- | 0.4 ± 0.8 | 0.4 ± 0.7 | 0.3 ± 0.6 | <0.001 |

| Median | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| (Range) | (0 – 14) | (0 – 5) | (0 – 4) | ||

| # of autoimmune diseases in family | 0 | 3189 (66.2 %) | 435 (68.1 %) | 350 (80.8 %) | <0.001 |

| 1-2 | 1377 (29.4 %) | 192 (30.1 %) | 82 (18.6 %) | ||

| 3+ | 111 (2.4 %) | 12 (1.9 %) | 8 (1.8 %) | ||

Family history of autoimmunity among subjects with JIA categories

We then compared the proportion of familial autoimmunity among first-degree relatives of children with the different JIA categories (Table 4). Overall, there were significant differences in the proportion of any familial autoimmunity among the JIA categories (p < 0.001). Additionally, among the categories, there was a significant difference in the proportion of children with first-degree relatives with a history of psoriasis (p < 0.001), ankylosing spondylitis (p < 0.001), spondyloarthropathy (p < 0.001), Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis (p = 0.001), acute anterior uveitis (p = 0.005), JIA (p = 0.047), RA (p < 0.001), and any inflammatory arthritis (p < 0.001).

Table 4.

Comparison of cases with different JIA categories with autoimmune disorders among first-degree relatives

| Family history of disease | JIA categorya | P-valueb | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 4441) | |||||||||

| Systemic | Poly RF(−) | Poly RF(+) | Oligo persistent | Oligo extended | Psoriatic | ERA | Undiff | ||

| (N = 355) | (N = 1313) | (N = 294) | (N = 1293) | (N = 340) | (N = 273) | (N = 451) | (N = 122) | ||

| Any autoimmune disease | 77 (21.7) | 408 (31.1) | 87 (29.6) | 344 (26.6) | 97 (28.5) | 146 (53.5) | 186 (41.2) | 54 (44.3) | <0.001 |

| Inflammatory arthritisc | 26 (7.3) | 169 (12.9) | 36 (12.4) | 137 (10.6) | 36 (10.6) | 5 2 (19.1) | 97 (21.5) | 24 (19.7) | <0.001 |

| Ankylosing spondylitis | 0 (0.0) | 4 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 7 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.7) | 37 (8.2) | 5 (4.1) | <0.001 |

| Spondyloarthropathy | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.3) | 3 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (1.8) | 17 (3.8) | 2 (1.6) | <0.001 |

| JIA | 10 (2.8) | 83 (6.3) | 10 (3.4) | 67 (5.2) | 13 (3.8) | 13 (4.8) | 32 (7.1) | 5 (4.1) | 0.047 |

| RA | 17 (4.8) | 95 (7.2) | 25 (8.5) | 76 (5.9) | 24 (7.1) | 37 (13.6) | 32 (7.1) | 16 (13.1) | <0.001 |

| Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis | 4 (1.1) | 35 (2.7) | 7 (2.4) | 27 (2.1) | 6 (1.8) | 6 (2.2) | 26 (5.8) | 6 (4.9) | 0.001 |

| Acute anterior uveitis | 0 (0.0) | 7 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0.005 |

| Psoriasis | 20 (5.6) | 78 (5.9) | 11 (3.7) | 70 (5.4) | 17 (5.0) | 96 (35.2) | 31 (6.9) | 20 (16.4) | <0.001 |

| SLE | 7 (2.0) | 26 (2.0) | 5 (1.7) | 17 (1.3) | 5 (1.5) | 2 (0.7) | 7 (1.6) | 5 (4.1) | 0.338 |

| Multiple Sclerosis | 3 (0.9) | 14 (1.1) | 2 (0.7) | 10 (0.8) | 6 (1.8) | 3 (1.1) | 2 (0.4) | 3 (2.5) | 0.410 |

| Autoimmune thyroiditis | 16 (4.5) | 74 (5.6) | 17 (5.8) | 62 (4.8) | 22 (6.5) | 23 (8.4) | 17 (3.8) | 6 (4.9) | 0.198 |

| Celiac | 1 (0.3) | 7 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 15 (1.2) | 2 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (1.3) | 1 (0.8) | 0.113 |

| Type 1 Diabetes | 12 (3.4) | 41 (3.1) | 14 (4.8) | 32 (2.5) | 8 (2.4) | 11 (4.0) | 14 (3.1) | 6 (4.9) | 0.406 |

| Other autoimmune | 12 (3.3) | 68 (5.1) | 10 (3.3) | 50 (3.8) | 12 (3.5) | 14 (5.1) | 25 (5.4) | 6 (4.7) | 0.504 |

achildren with missing JIA category information were excluded. All values are N (%)

bSignificance values for overall differences between JIA categories

cInflammatory arthritis includes AS, spondyloarthropathy, JIA and RA

Discussion

Autoimmune disorders are common, estimated to affect 5-10 % of the population. Clinical and genetic studies support the hypothesis that clinically distinct autoimmune disorders share common genetic susceptibility factors [1, 16, 17]. Familial aggregation of SLE, RA and other autoimmune diseases have been reported in probands with SLE [18]. Previously studies of small cohorts have shown familial aggregation of autoimmunity in JIA, JDM and cSLE [9–11]. In a study of 69 subjects with cSLE, 32 % of subjects had one or more first degree relatives with autoimmune diseases which matches findings from our study [10]. However, there have not been systematic investigations of large cohorts of children with JIA, SLE and JDM to determine if there are specific patterns of familial clustering with these phenotypes.

Our results suggest that the prevalence of autoimmunity is increased among first degree relatives of subjects with JIA and cSLE compared to those of JDM. Relatives of subjects with cSLE had an increased prevalence of SLE, and relatives of subjects with JIA were enriched for inflammatory arthropathies. Relatives of children with cSLE also had a higher prevalence of type-1 diabetes compared to relatives of cases with JIA or JDM. These results highlight the complex nature of familial autoimmunity suggesting that while prevalence of clinically distinct autoimmune phenotypes are increased among family members of cases with JIA, cSLE and JDM, there are distinct patterns of familial clustering of diseases among these phenotypes.

Our results suggest that familial autoimmunity is lower in JDM compared to JIA or cSLE. Since the sample sizes of our JDM and cSLE cohorts were of similar magnitude, we believe that this is a true difference and not influenced by the potential number of relatives. One possible reason for this observation could be due to a potentially greater contribution of environmental factors to JDM compared to JIA or cSLE. While genome wide association studies of JIA [19] and SLE [20, 21] have resulted in the discovery of a number of associated loci both within and outside the MHC region, in inflammatory myopathies, only HLA variants are associated at genome wide levels of significance, although the sample sizes for inflammatory myopathies was modest at 1700 cases [22]. It is also possible that susceptibility genes that underlie JDM might be different compared to JIA and/or cSLE. Emerging studies of multiple autoimmune phenotypes using shared controls might allow for a better understanding of shared genetic associations between clinically distinct phenotypes, which in turn might have implications towards understanding their pathophysiology and therapy [23]. Future investigations of subjects in families with multiple autoimmune disorders to characterize shared genomic, transcriptomic and proteomic factors would further enhance our understanding of the complex relationship between different autoimmune phenotypes.

When we compared the different JIA categories, we found that systemic JIA cases had lower proportion of first degree relatives with any autoimmune disease (21.7 %) compared to other JIA categories, which is consistent with the idea that systemic JIA may be phenotypically and genetically distinct from other JIA categories [24]. Since family history of psoriasis and spondyloarthropathy is part of the criteria for classifying patients into psoriatic JIA and ERA respectively, this could have biased the observed higher prevalence of autoimmunity among relatives of psoriatic JIA and ERA cases. Interestingly the prevalence of SLE, autoimmune thyroiditis, MS, celiac disease and type 1 diabetes did not differ significantly between relatives of different JIA categories.

Our study had several strengths. The data for the CARRA Registry was collected from a majority of pediatric rheumatology centers in the USA, which means our results apply to a broad population of childhood rheumatic diseases. In addition to being the first to compare familial autoimmunity among JIA, cSLE and JDM, our study comprised of large cohorts with JIA, cSLE and JDM. Our JIA cohort was also sufficiently large which allowed us to investigate differences between different JIA categories.

Our study has potential limitations as well. The CARRA Registry did not collect family history of idiopathic inflammatory myopathy specifically. This could have resulted in an underrepresentation of inflammatory myopathy in these families. However, two smaller studies of probands with idiopathic inflammatory myopathies did not find an increased prevalence of first degree relatives with inflammatory myopathy [9, 25]. Furthermore, an “other” category was included which might have expected to capture information if subjects with JDM had increased numbers of relatives with inflammatory myopathies. The CARRA Registry also did not collect individual data on which relative had the autoimmune disorder or the number of first-degree relatives to provide a denominator. We do not believe that this limitation affects our conclusion that compared to first degree relatives of JDM cases, there is increased autoimmunity among first degree relatives of patients with JIA and cSLE. Since families of probands with JIA, cSLE and JDM completed the same baseline demographic forms it is unlikely that there was bias in reporting of first degree relatives with autoimmune disorders between JIA, cSLE and JDM. The lack of data to discriminate autoimmunity status of individual relatives limits us from estimating the prevalence of autoimmunity among relatives or potential parent of origin effects, but we do not believe there to be inherent differences in number of relatives among JIA, cSLE or JDM families. Finally, our subjects are from North America, and majority (85 %) were Caucasian, which might limit the generalizability of the study to other regions and ethnicities.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have shown JIA and cSLE cases more often have first-degree relatives with autoimmunity compared to JDM cases. The demonstration that a greater proportion of JIA cases have first-degree relatives with inflammatory arthritis, and a greater proportion of cSLE cases have first-degree relatives with SLE suggests that there are distinct patterns of familial autoimmunity. Future studies, including investigation of genomic and proteomic biomarkers among subjects with different autoimmune phenotypes as well as their relatives would substantially improve our understanding of the complex interplay between different autoimmune phenotypes.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Prahalad is supported by grants from The National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS) (01-AR060893), Arthritis Foundation and The Marcus Foundation Inc. CARRA Registry is supported by grants from NIAMS (RC2-AR058934), Friends of CARRA, the Arthritis Foundation, and the Duke Clinical Research Institute. Dr. Thompson is supported by grants from NIAMS (P01-AR048929 and P30-AR0470363), The Arthritis Foundation and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Research Foundation. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIAMS or the National Institutes of Health.

The authors would like to thank all participants and hospital sites that recruited patients for the CARRA Registry. The authors thank the following CARRA Registry site principal investigators and research coordinators: L. Abramson, E. Anderson, M. Andrew, N. Battle, M. Becker, H. Benham, T. Beukelman, J. Birmingham, P. Blier, A. Brown, H. Brunner, A. Cabrera, D. Canter, D. Carlton, B. Caruso, L. Ceracchio, E. Chalom, J. Chang, P. Charpentier, K. Clark, J. Dean, F. Dedeoglu, B. Feldman, P. Ferguson, M. Fox, K. Francis, M. Gervasini, D. Goldsmith, G. Gorton, B. Gottlieb, T. Graham, T. Griffin, H. Grosbein, S. Guppy, H. Haftel, D. Helfrich, G. Higgins, A. Hillard, J.R. Hollister, J. Hsu, A. Hudgins, C. Hung, A. Huttenlocher, N. Ilowite, A. Imlay, L. Imundo, C.J. Inman, J. Jaqith, R. Jerath, L. Jung, P. Kahn, A. Kapedani, D. Kingsbury, K. Klein, M. Klein-Gitelman, A. Kunkel, S. Lapidus, S. Layburn, T. Lehman, C. Lindsley, M. Macgregor-Hannah, M. Malloy, C. Mawhorter, D. McCurdy, K. Mims, N. Moorthy, D. Morus, E. Muscal, M. Natter, J. Olson, K. O’Neil, K. Onel, M. Orlando, J. Palmquist, M. Phillips, L. Ponder, S. Prahalad, M. Punaro, D. Puplava, S. Quinn, A. Quintero, C. Rabinovich, A. Reed, C. Reed, S. Ringold, M. Riordan, S. Roberson, A. Robinson, J. Rossette, D. Rothman, D. Russo, N. Ruth, K. Schikler, A. Sestak, B. Shaham, Y. Sherman, M. Simmons, N. Singer, S. Spalding, H. Stapp, R. Syed, E. Thomas, K. Torok, D. Trejo, J. Tress, W. Upton, R. Vehe, E. von Scheven, L. Walters, J. Weiss, P. Weiss, N. Welnick, A. White, J. Woo, J. Wootton, A. Yalcindag, C. Zapp, L. Zemel, and A. Zhu.

Footnotes

Competing interests

Dr. Prahalad has served on an advisory board for Novartis, but this had no bearing on the work described in this manuscript. None of the other authors have any competing interests in the manuscript.

Authors’ contributions

SP, CDL, SDT conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination. SP drafted the manuscript. CM assisted with study design and statistical analysis. LP recruited participants and organized participant data. SAH, KRS, LBV, recruited subjects and participated in data interpretation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Sampath Prahalad, Phone: (404) 727 8949, Email: sprahal@emory.edu.

Courtney E. McCracken, Email: courtney.mccracken@emory.edu

Lori A. Ponder, Email: lori.ponder@choa.org

Sheila T. Angeles-Han, Email: sangele@emory.edu

Kelly A. Rouster Stevens, Email: kelly.a.rouster-stevens@emory.edu

Larry B. Vogler, Email: lvogler@emory.edu

Carl D. Langefeld, Email: clangefe@wakehealth.edu

Susan D. Thompson, Email: Susan.thompson@cchmc.org

References

- 1.Remmers EF, Plenge RM, Lee AT, Graham RR, Hom G, Behrens TW, et al. STAT4 and the risk of rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:977–86. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Begovich AB, Carlton VE, Honigberg LA, Schrodi SJ, Chokkalingam AP, Alexander HC, et al. A missense single-nucleotide polymorphism in a gene encoding a protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTPN22) is associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75:330–7. doi: 10.1086/422827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bottini N, Vang T, Cucca F, Mustelin T. Role of PTPN22 in type 1 diabetes and other autoimmune diseases. Semin Immunol. 2006. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Chinoy H, Platt H, Lamb JA, Betteridge Z, Gunawardena H, Fertig N, et al. The protein tyrosine phosphatase N22 gene is associated with juvenile and adult idiopathic inflammatory myopathy independent of the HLA 8.1 haplotype in British Caucasian patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:3247–54. doi: 10.1002/art.23900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Somers EC, Thomas SL, Smeeth L, Hall AJ. Autoimmune diseases co-occurring within individuals and within families: a systematic review. Epidemiology. 2006;17:202–17. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000193605.93416.df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Somers EC, Thomas SL, Smeeth L, Hall AJ. Are individuals with an autoimmune disease at higher risk of a second autoimmune disorder? Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169:749–55. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stagi S, Giani T, Simonini G, Falcini F. Thyroid function, autoimmune thyroiditis and coeliac disease in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2005;44:517–20. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prahalad S, O'Brien E, Fraser AM, Kerber RA, Mineau GP, Pratt D, et al. Familial aggregation of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:4022–7. doi: 10.1002/art.20677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Niewold TB, Wu SC, Smith M, Morgan GA, Pachman LM. Familial aggregation of autoimmune disease in juvenile dermatomyositis. Pediatrics. 2011;127:e1239–46. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walters HM, Pan N, Moorthy LN, Ward MJ, Peterson MG, Lehman TJ. Patterns and influence of familial autoimmunity in pediatric systemic lupus erythematosus. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2012;10:22. doi: 10.1186/1546-0096-10-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prahalad S, Shear ES, Thompson SD, Giannini EH, Glass DN. Increased prevalence of familial autoimmunity in simplex and multiplex families with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:1851–6. doi: 10.1002/art.10370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ringold S, Beukelman T, Nigrovic PA, Kimura Y, Investigators CRSP. Race, ethnicity, and disease outcomes in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a cross-sectional analysis of the Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance (CARRA) Registry. J Rheumatol. 2013;40:936–42. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.121147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pelajo CF, Angeles-Han ST, Prahalad S, Sgarlat CM, Davis TE, Miller LC, et al. Evaluation of the association between Hispanic ethnicity and disease activity and severity in a large cohort of patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Rheumatol Int. 2013;33:2549–54. doi: 10.1007/s00296-013-2773-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boneparth A, Ilowite N. Comparison of renal response parameters for juvenile membranous plus proliferative lupus nephritis versus isolated proliferative lupus nephritis: a cross-sectional analysis of the CARRA Registry. Lupus. 2014;23:898–904. doi: 10.1177/0961203314531841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petty RE, Southwood TR, Manners P, Baum J, Glass DN, Goldenberg J, et al. International League of Associations for Rheumatology classification of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: second revision, Edmonton, 2001. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:390–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhernakova A, van Diemen CC, Wijmenga C. Detecting shared pathogenesis from the shared genetics of immune-related diseases. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:43–55. doi: 10.1038/nrg2489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prahalad S, Hansen S, Whiting A, Guthery SL, Clifford B, McNally B, et al. Variants in TNFAIP3, STAT4, and C12orf30 loci associated with multiple autoimmune diseases are also associated with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:2124–30. doi: 10.1002/art.24618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alarcon-Segovia D, Alarcon-Riquelme ME, Cardiel MH, Caeiro F, Massardo L, Villa AR, et al. Familial aggregation of systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, and other autoimmune diseases in 1,177 lupus patients from the GLADEL cohort. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:1138–47. doi: 10.1002/art.20999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hinks A, Cobb J, Marion MC, Prahalad S, Sudman M, Bowes J, et al. Dense genotyping of immune-related disease regions identifies 14 new susceptibility loci for juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Nat Genet. 2013;45:664–9. doi: 10.1038/ng.2614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harley IT, Kaufman KM, Langefeld CD, Harley JB, Kelly JA. Genetic susceptibility to SLE: new insights from fine mapping and genome-wide association studies. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:285–90. doi: 10.1038/nrg2571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun C, Molineros JE, Looger LL, Zhou XJ, Kim K, Okada Y, et al. High-density genotyping of immune-related loci identifies new SLE risk variants in individuals with Asian ancestry. Nat Genet. 2016;48:323–30. doi: 10.1038/ng.3496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller FW, Chen W, O'Hanlon TP, Cooper RG, Vencovsky J, Rider LG, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies HLA 8.1 ancestral haplotype alleles as major genetic risk factors for myositis phenotypes. Genes Immun. 2015;16:470–80. doi: 10.1038/gene.2015.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li YR, Li J, Zhao SD, Bradfield JP, Mentch FD, Maggadottir SM, et al. Meta-analysis of shared genetic architecture across ten pediatric autoimmune diseases. Nat Med. 2015;21:1018–27. doi: 10.1038/nm.3933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martini A. Systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Autoimmun Rev. 2012;12:56–9. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2012.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ginn LR, Lin JP, Plotz PH, Bale SJ, Wilder RL, Mbauya A, et al. Familial autoimmunity in pedigrees of idiopathic inflammatory myopathy patients suggests common genetic risk factors for many autoimmune diseases. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:400–5. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199803)41:3<400::AID-ART4>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]