Abstract

Cyclin G-associated kinase (GAK) is a serine/threonine kinase that features high homology outside its kinase domain with auxilin. Like auxilin, GAK has been shown to be a cofactor for uncoating clathrin vesicles in vitro. We investigated epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor-mediated signaling in cells, in which GAK is down-regulated by small hairpin RNAs. Here, we report that down-regulation of GAK by small hairpin RNA has two pronounced effects on EGF receptor signaling: (i) the levels of receptor expression and tyrosine kinase activity go up by >50-fold; and (ii) the spectrum of downstream signaling is significantly changed. One very obvious result is a large increase in the levels of activated extracellular signal-regulated kinase 5 and Akt. These two effects of GAK down-regulation result from, at least in part, alterations in receptor trafficking, the most striking of which is the persistence of EGF receptor in altered cellular compartment along with activated extracellular signal-regulated kinase 5. The alterations resulting from GAK down-regulation can have distinctive biological consequences: In CV1P cells, down-regulation of GAK results in outgrowth of cells in soft agar, raising the possibility that loss of GAK function may promote tumorigenesis.

Cyclin G-associated kinase (GAK), also known as auxilin II (1, 2), is a 160-kDa protein, which is highly homologous to auxilin I, with the notable exception of a kinase domain found at the N terminus of GAK, and totally absent in auxilin I. Unlike auxilin I, which has been reported to be expressed only in neurons, GAK is ubiquitously expressed. In vitro GAK, like auxilin I, is known to assist heat shock cognate 70 (Hsc70) in uncoating clathrin-coated vesicles (3, 4). Thus, GAK is thought to function in trafficking just after the step regulated by dynamin. GAK also represents a major portion of the kinase activity in clathrin-coated vesicles (5). GAK has been reported to phosphorylate the μ2 subunit of adaptor protein (AP)2, as has AAK1, the protein kinase most closely related to GAK in its catalytic domain (4–9). In the case of AAK1, phosphorylation of μ2 has been shown to have functional consequences in promoting the recruitment of AP2 to internalization motifs found on membrane-bound receptors (9). Overexpression of either GAK or AAK1 is sufficient to impair internalization of the transferrin receptor (4, 7, 10). Thus, GAK may function in both the ultimate disassembly of clathrin-coated vesicles through its auxilin homology domains and in their formation through its kinase domain although there is no direct evidence that GAK can mimic AAK1 in regulating vesicle formation (6–9). Because so many kinases play key regulatory roles, it occurred to us that GAK might represent an important regulatory point in receptor trafficking. We were particularly interested to see whether GAK might regulate receptor tyrosine kinases, such as the EGF receptor (EGFR), because this class of receptor is key to normal cell function and transformation, and because the signaling and trafficking of receptor tyrosine kinases is well characterized.

EGFR-mediated signaling results in cell proliferation or differentiation. Elevated levels or inappropriate activation of the EGFR is associated with increased propensity for cell transformation and tumor formation (11, 12). Upon ligand stimulation, EGFRs are activated by autophosphorylation, internalized, at least in part through clathrin-mediated endocytosis, and sorted to early, and subsequently, late endosomes (13–16). Internalized receptors then are delivered to the lysosome and degraded or recycled to the cell surface. As the receptor transits this three-dimensional path through the cell's interior, various EGF-mediated signaling molecules are activated including extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1/2 (ERK1/2) via the Ras/raf pathway (11, 17–21), and Akt via the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway (22–24). Previous studies have indicated that blocking receptor trafficking at a particular point can have significant effects on receptor signaling. For instance, studies by Vieira et al. (25) showed that expression of a dominant negative allele of dynamin, a GTPase involved in clathrincoated vesicle fission, inhibits endocytosis of EGFR, and consequently, ERK1/2 activation is attenuated. However, the roles of trafficking events subsequent to formation of clathrin-coated vesicles in the regulation of EGFR signaling remain relatively unknown.

In the present report, we examine the effects of down-regulating GAK expression upon EGFR signaling. By using small hairpin RNA to reduce GAK levels by >90%, we find that both the levels of EGFR in the cells and the signaling downstream from the receptor are strikingly altered. At least some of these dramatic changes are likely due to changes in receptor trafficking. At the biological level, GAK down-regulation can have significant effects on cell growth. These results suggest that GAK plays a pivotal role in regulating not only receptor trafficking but also receptor signaling and function.

Materials and Methods

DNA-Based RNA Interference (RNAi) Constructs and Cell Culture. The retroviral pSuper vector used in the study was the same as that described in Brummelkamp et al. (26). Selected sequences were submitted to blast searches against the human genome sequence to ensure only GAK mRNA is targeted. For generation of stable GAK knockdown cells, HeLa (a human cervix epithelioid carcinoma cell line, American Type Culture Collection) or CV1P (an African green monkey kidney cell line) cells were infected with the retroviral pSuper vectors containing either one of two hairpin constructs capable of generating 19-nt duplex RNAi oligonucleotides corresponding to human GAK sequences starting at the 145th base in the coding sequence (denoted 145) or the 525th base (denoted 525). Cells were cultured in DMEM with 10% FCS, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin in 10% CO2 humidified incubator. When necessary, 1.5 μg/ml puromycin was included for selection. A431 cells (a human epidermoid carcinoma cell line, American Type Culture Collection) are also used to compare the expression level of EGFR.

Abs. The following Abs were used: mAb clone 1C2 (anti-GAK, Medical & Biological Laboratories); mAb clone MA1 065 (anti-clathrin heavy chain, Affinity BioReagents, Golden, CO); mAb clone14 (anti-EEA1, BD Transduction Laboratories); 4G10 (antiphosphotyrosine, Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY); mAb EGFR (528) Ab (Santa Cruz Biotechnology); polyclonal EGFR (1005) Ab (Santa Cruz Biotechnology); polyclonal phospho-p42/44 mitogen-activated protein kinase (Thr-202/Tyr-204) Ab (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA); polyclonal p42/44 Ab (Cell Signaling Technology); polyclonal phospho-ERK5 (Thr-218/Tyr-220) Ab (Cell Signaling Technology); polyclonal ERK5 Ab (Sigma); polyclonal phospho-Akt (Ser-473) or (Thr-308) Abs (Cell Signaling Technology); and polyclonal Akt Ab (Cell Signaling Technology).

Western Blot Analysis and Immunoprecipitation. Cells were seeded in 100-mm dishes and grown to ≈75% confluence in a 10% CO2 humidified incubator. The next day, cells were serum-starved with DMEM without serum for 24 h wherever necessary. Cells were incubated with 50 ng/ml EGF (Upstate Biotechnology) for indicated times. Cells were then harvested and lysed with Nonidet P-40 lysis buffer (50 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.5/150 mM NaCl/1% Nonidet P-40/5 μg of leupeptin per ml/5 μg of pepstatin per ml/0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride/1 mM sodium fluoride/100 μM sodium vanadate/10 mM β-glycerol phosphate) for 10 min on ice. Extracts were cleared of cell debris by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min in a microcentrifuge at 4°C. Equal amounts of protein lysate from each dish of cell lines was immunoprecipitated by mAb EGFR (528) Ab (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 2 h and then 45 μl of protein A Sepharose beads for 45 min. The beads were washed three times with Nonidet P-40 lysis buffer. For Western blotting, the immunoprecipitates or protein lysates were boiled with one third volume of 3× SDS buffer (150 mM Tris·HCl, pH 6.8/300 mM DTT/6% SDS/0.3% Bromophenol blue/30% glycerol) and separated on a 7.5% or 10% SDS polyacrylamide gel wherever applicable, followed by transfer to a poly(vinylidene difluoride) membrane. The blots were then blocked with 5% dry milk or 2% gelatin (for 4G10) and incubated with various Abs in appropriate dilutions as follows: EGFR Ab, phopho-ERK5, ERK5, phopho-p42/44, and p42/44; phospho-Akt, total Akt, and antiphosphotyrosine Ab (4G10) overnight or 45 min (4G10), washed with Tris-buffered saline-Tween (150 mM NaCl/10 mM Tris·HCl/0.2% Tween 20), then incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit or anti-mouse secondary Ab (Amersham Biosciences) for 30 min, washed again, and developed by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Biosciences). The signals were visualized by exposure to Kodak X-Omat blue XB-1 film.

Cell Surface-Associated EGFR Assay. Cells were seeded in 60-mm dishes and grown to ≈75% confluence in a 10% CO2 humidified incubator. The next day, cells were serum-starved with DMEM without serum for 24 h. Cells were stimulated with 50 ng/ml EGF (Upstate Biotechnology) for the indicated times. Biotinylation of intact cells were carried out as described by Levy-Toledano et al. (27). Briefly, cells were rinsed with cold PBS twice and incubated on ice for 2 min. Cells were then incubated with 3 ml of biotinylation buffer [0.4 mg/ml NHS-LC-biotin (Pierce) in 50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 8.5/110 mM NaCl/0.1% NaN3] on ice for 20 min with occasional mixing. Cells were then washed three times with ice-cold PBS buffer plus 0.1% NaN3 (pH 7.4). Cells lysates were immunoprecipitated with mAb EGFR Ab and subsequently, Western blotting was performed as described above. The blot was then incubated with streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase (Amersham Biosciences) for 30 min, and washed and developed by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Biosciences). The signals were visualized by exposure to Kodak X-Omat blue XB-1 film.

EGF Internalization Assay and Indirect Immunofluorescence. Cells stably expressing a DNA-based RNAi construct targeting GAK were seeded on eight-well Labtek chamber slides. Twenty-four hours later, cells were serum-starved in DMEM without serum overnight. The next day, cells were incubated with 0.5 μg/ml tetramethylrhodamine-conjugated EGF (Molecular Probes) for 1 h on ice and then for 40 min at 37°C. Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, washed with PBS, permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min, and blocked with 10% goat serum for 1 h. Primary Abs were applied for 1 h and cells were then washed with PBS. Cy2-conjugated secondary Abs (The Jackson Laboratory) were applied and incubated for 1 h. The same cells were then counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; 1 μg/ml, Sigma) and mounted with Fisher Scientific mounting media. Cells were visualized with a Zeiss confocal microscope LSM510META/NLO at ×63 magnification and images were captured by Zeiss confocal microscope software Version 3.2.

BrdUrd Incorporation Assay. Cells grown on chamber slides were serum-starved overnight and labeled with BrdUrd for 15 h. Cells were fixed and permeabilized as described above. Cells were then incubated with a mAb (Amersham Biosciences) against BrdUrd for 1 h. Cy2-conjugated secondary Abs (The Jackson Laboratory) were applied and were incubated for 1 h. Cells were washed and counterstained with DAPI (1 μg/ml, Sigma) and mounted with Fisher Scientific mounting media. BrdUrd-positive cells were counted among DAPI-stained cells in at least 10 randomly selected fields on each slide under a Nikon Eclipse TE300 fluorescence microscope.

Soft Agar Assay. A total of 5 × 104 CV1P cells (vector control or 525) as single-cell suspensions in 2 ml of 0.27% Bacto agar were overlayed on top of 0.6% agar in 60-mm culture dish. In each experiment, at least two or more duplicate plates were prepared for each cell line. DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS and 1% streptomycin/penicillin was used as media for agar. Colonies were counted after incubation at 37°C in a 10% CO2-humidified incubator for 21 days under a Nikon SMZ microscope (magnification: ×7).

Results

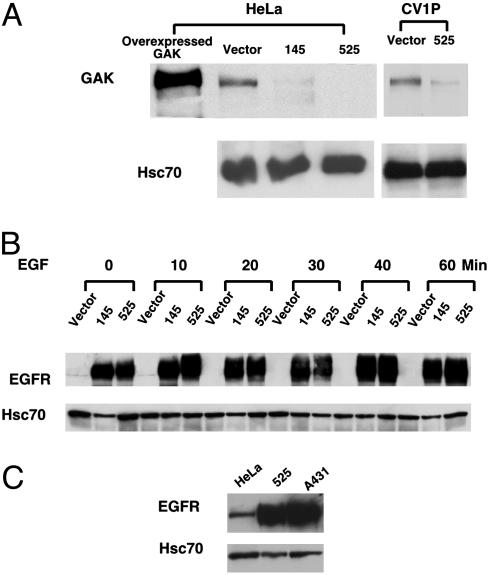

Down-Regulation of GAK by Small Hairpin RNA Dramatically Enhances EGFR Expression. We used small hairpin RNA techniques to down-regulate endogenous GAK in mammalian cells. To compare our findings with earlier work using dominant-negative dynamin constructs (25), we focused our studies on EGFR signaling in HeLa cells. We also down-regulated GAK in CV1P cells to assess the biological consequences of GAK down-regulation. Here, we report data obtained from HeLa cells in which GAK expression was stably down-regulated through either of two different RNAi constructs. We have obtained similar signaling results by using oligonucleotide-based methodologies to transiently down-regulate GAK in HeLa, COS7, and CVIP cells (data not shown). For generation of stable GAK knockdown in HeLa and CV1P cells, cells were infected with retroviral pSuper vectors containing either one of two hairpin constructs capable of generating 19-nt duplex RNAi oligonucleotides corresponding to human GAK sequences starting at the 145th base in the coding sequence (denoted 145) or the 525th base (denoted 525, ref. 26). As shown in Fig. 1A, GAK protein levels in the resulting HeLa knockdown cell lines were reduced at least 90% compared with GAK levels in vector control cells (The 525 construct was slightly better than the 145 construct). In CV1P cells, however, only the 525 cell line, but not the 145 cell line, shows a significant reduction in GAK expression (Fig. 1A and data not shown). We tried to test the possibility of reversing the phenotypes observed upon GAK knockdown through GAK reexpression; however, expression of the wild-type human GAK by using available promoters resulted in GAK accumulation in apparent vesicular aggregates (4).

Fig. 1.

Down-regulation of GAK dramatically increases EGFR expression in HeLa cells. (A) GAK expression was stably down-regulated in HeLa and CV1P cells. Cells were infected with retroviral pSuper vectors encoding either one of two hairpin constructs capable of generating 19-nt duplex RNAi oligonucleotides corresponding to human GAK sequences, starting at the 145th base in the coding sequence (denoted 145) or the 525th base (denoted 525). Western blotting of total cell lysates was carried out by using a mAb against GAK. As a positive control, a lysate from cells transiently overexpressing GAK was included. Levels of Hsc70 were used as loading controls. (B) EGFR expression was dramatically enhanced in GAK knockdown cells. Cells were serum-starved overnight and stimulated with 50 ng/ml EGF for the indicated times. EGFR was detected by Western blotting using an Ab against it. (C) The level of EGFR expression in GAK knockdown cells was ≈75% of that of A431 cells. Cells were serum-starved overnight and EGFR expression was detected as described in B. Levels of Hsc70 were used as loading controls.

We first characterized the gross levels of EGFR expression in the HeLa knockdown cells. To our surprise, in GAK knockdown cells under serum starvation, EGFR levels were significantly increased (>50-fold) compared with the vector control cells (Fig. 1B). To better characterize the level of EGFR overexpression in GAK knockdown cell lines, we compared the EGFR numbers in knockdown cells with those in the tumor cell line A431, known to express high levels of EGFR. Fig. 1C shows that the level of EGFR expression in knockdown cells is about three fourths of that seen in A431 cells [reported to be 2 million EGFR molecules per cell (28)]. We also measured the levels of EGFR expression as a function of time after EGF stimulation. Normally, after cells are treated with EGF, the EGFR is internalized and degraded rapidly in lysosomes (29). However, the elevated level of EGFR in knockdown cells persisted for hours after EGF stimulation (Fig. 1B and data not shown). This lack of down-regulation seen upon GAK knockdown may explain the enhanced levels of EGFR expression. A pulse–chase experiment showed that the half-life of the EGF stimulated EGFR in knockdown cells is longer than 4 h (versus <1 h in control cells; data not shown).

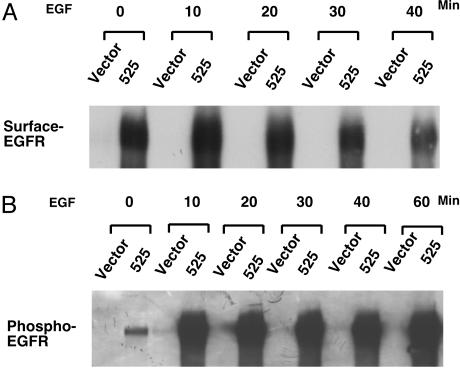

Down-Regulation of GAK Results in Elevated Levels of EGFR on the Cell Surface and Enhanced EGFR Activation. We next wished to determine whether the EGFR in GAK knockdown cells is localized at the cell surface or at some abnormal intracellular location. To examine cell-surface exposure, receptors on the surface of living cells were labeled with biotin. Subsequently, the biotinylated receptors were isolated by means of streptavidin affinity and visualized by Western blotting with an anti-EGFR antiserum. Fig. 2A shows that levels of surface accessible EGFR in knockdown cells are approximately >50-fold higher than the levels seen in controls before EGF stimulation. This finding suggests that most of the “excess” receptors in the knockdown cells are located normally, a fact which was later born out by immunofluorescence studies (see below). Surface-associated receptors displayed a significant decrease by 30 min after EGF stimulation in knockdown cells. By 60 min after EGF stimulation, the number of surface-associated EGFRs in knockdown cells had decreased dramatically, indicating that most, but not all of the receptors, had been internalized.

Fig. 2.

In GAK knockdown cells, EGFR remains surface-associated for extended periods after EGF stimulation and displays enhanced kinase activity. (A) The level of surface-associated EGFR in GAK knockdown cell remains high for a prolonged time. Cells were serum-starved overnight and incubated with 50 ng/ml EGF for indicated times. Cells were surface-labeled with biotin at the indicated times, then the biotinylated receptors were isolated by means of streptavidin affinity and visualized by Western blotting with an EGFR Ab. (B) EGFR in GAK knockdown cells displays high tyrosine kinase activity in response to EGF stimulation. Cells were serum-starved overnight and incubated with 50 ng/ml EGF for indicated times. Total EGFR in cells was immunoprecipitated with EGFR Ab and blotted with an Ab against phosphorylated tyrosine (4G10).

To examine the activation state of the EGFR in GAK knockdown cells, the level of tyrosine phosphorylation of immunoprecipitated EGFR from knockdown cells was examined after EGF stimulation. Fig. 2B shows that the EGFR in knockdown cells was highly phosphorylated on tyrosines upon EGF stimulation. There seemed to be at least 50-fold higher levels of activated receptors present compared with control cells, which indicated that most of the additional receptors were functional. Receptor activation was sustained for at least 60 min. Notably, there is a substantial level of activated EGFR in the knockdown cells even after serum starvation, indicating that a subset of the EGFR is constitutively active. Thus, down-regulation of GAK elicits dramatic effects on the level and activation of the EGFR.

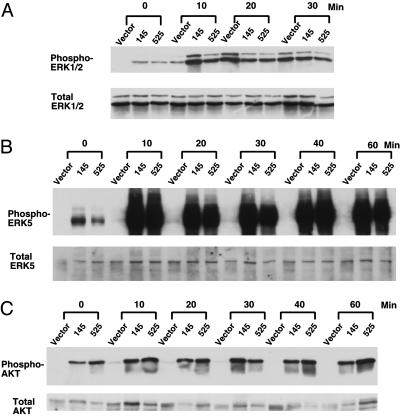

Down-Regulation of GAK Differentially Alters Signaling Downstream of the EGFR. To investigate whether EGFR signaling is also altered in GAK knockdown cells, we analyzed several known EGFR-mediated signaling pathways. Previous work by Vieira et al. (25) had indicated that overexpression of a dominant-negative dynamin allele suppresses EGFR-mediated ERK1/2 signaling, so we examined the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases in the knockdown cells. Under conditions of serum starvation, there was constitutive activation of ERK1/2 in knockdown cells but not in control cells (Fig. 3A). This finding is consistent with the presence of constitutively active EGFR in the knockdown cells. Ten minutes after EGF addition, the level of activated ERK1/2 is higher in knockdown cells than in controls. However, the difference between control and knockdown cells is diminished by 20 min after EGF stimulation, and control cells actually display higher levels of activated ERK1/2 at later times. This result is consistent with the idea that ERK1/2 activation occurs more rapidly in the knockdown cells than in control cells. On the other hand, activation of ERK5, a kinase involved in cell proliferation and survival, is greatly up-regulated in the knockdown cells (Fig. 3B and refs. 30–32). As observed in the case of ERK1/2 activation, there is a substantial level of active ERK5 under serum starvation. However, in contrast to ERK1/2 activation, activation of ERK5 is ≈100-fold higher in the knockdown cells than in controls, and this activation is sustained for >60 min (Fig. 3B and data not shown). We also examined the activation of several other signaling proteins. We found that tyrosine phosphorylation of p85, a regulatory subunit of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, was greatly elevated in knockdown cells (data not shown). Consequently, the serine/threonine kinase Akt, a downstream target of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, was highly activated in knockdown cells (Fig. 3C). On the other hand, tyrosine phosphorylation of SHC and phospholipase C γ was either suppressed (SHC) or not affected (PLC-γ) (data not shown). Whereas it is not surprising that down-regulation of GAK affects signaling, the differential regulation of ERK1/2 versus ERK5 suggests that GAK plays a more complex role in cell signaling than expected.

Fig. 3.

Down-regulation of GAK differentially enhances EGFR-dependent signaling. Cells were serum-starved overnight and stimulated with 50 ng/ml EGF for indicated times. Western blot analysis was carried out by probing with an Ab against phosphorylated ERK1/2 or total ERK1/2(A); and an Ab against phosphorylated ERK5 or total ERK5 (B); or an Ab against phosphorylated Akt or total Akt (C).

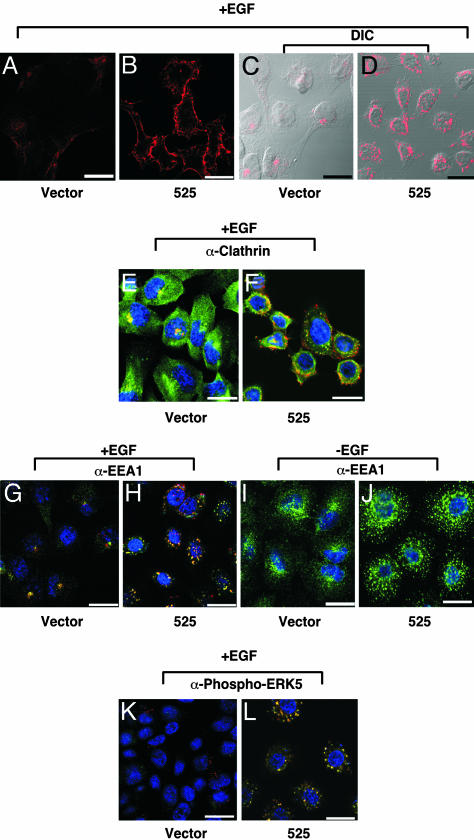

Down-Regulation of GAK Alters EGFR Trafficking. In an attempt to understand the mechanism by which down-regulation of GAK might bring about such complex effects, we examined intracellular receptor trafficking in the knockdown cells by using confocal microscopy. We first used a fluorescently labeled EGF probe to track the receptor itself. As seen in Fig. 4, if cells are left on ice after application of ligand, the EGF probe is primarily seen on the plasma membrane in both knockdown (Fig. 4B) and control cells (Fig. 4A), with a much stronger signal evident on the knockdown cells. After cells were left at 37°C for 40 min to allow EGF internalization, the probe relocalizes to the cytoplasm in the knockdown cells but is clearly mislocalized compared with controls (Fig. 4D versus C). By immunostaining with multiple markers, we found that in GAK knockdown cells, internalized EGFR was not colocalized with the clathrin AP2 (data not shown) and was partially colocalized with clathrin (Fig. 4F, compare with E). Interestingly, EGFR was well colocalized with EEA1, an early endosome marker (Fig. 4H, compared with G). We also examined whether any of these markers were relocalized in the knockdown cells in the absence of EGF stimulation. We observed that clathrin and AP2 localization was not affected (data not shown). However, EEA1 was mislocalized in knockdown cells even in the absence of EGF (Fig. 4J, compared with I). We also examined the localization of downstream signaling molecules. Whereas the relocalization of ERK1/2 to the nucleus was not significantly altered compared with EGF-treated control cells (data not shown), we observed that ERK5 colocalized with receptors in the altered endosomal compartment (Fig. 4 L compared with K).

Fig. 4.

Down-regulation of GAK alters intracellular trafficking of EGFR. Cells grown on chamber slides were serum-starved overnight. Cells were then incubated with 0.5 μg/ml rhodamine-conjugated EGF on ice for 1 h. (A–D) Cells were either fixed immediately (A and B) or incubated at 37°C in a 10% CO2 humidified incubator for 40 min (C and D), then fixed and counterstained with DAPI (blue) to localize the nucleus of the cell being studied. (E–L) Alternatively, cells were incubated with (E–H, K, and L) or without (I and J) rhodamineconjugated EGF (red signal) and fixed as described above, then incubated with primary Ab as indicated below. In each case, the Ab signal is green. Overlap of the EGF signal in red and Ab signal in green is yellow. Cells were visualized with a Zeiss LSM 510 META/NLO confocal microscope at ×63 magnification and images were captured by Zeiss confocal microscope software Version 3.2. (A and B) Enhanced levels of EGFR visualized on the surface of GAK knockdown cells. Fluorescently labeled EGF is used to visualize EGFR on the plasma membrane without internalization. (C and D) EGFR is mislocalized after EGF stimulation. Fluorescently labeled EGF is used to visualize EGFR at 40 min after stimulation. Images captured by using differential interference contrast (DIC) and fluorescence microscopy combined. (E and F) EGFR partially colocalizes with clathrin. Costaining with an Ab against clathrin in addition to fluorescently labeled EGF is used to determine the localization of clathrin in the compartment containing the EGFR. (G and H) EGFR colocalizes with EEA1 in GAK knockdown cells. Costaining with an Ab against EEA1, an early endosome marker, in addition to fluorescently labeled EGF is used to determine the degree of colocalization between EEA1 and EGFR. (I and J) EEA1 is mislocalized even in the absence of receptor stimulation. An Ab against EEA1 is used to show the status of the early endosome in the absence of EGF stimulation. (K and L) Activated ERK5 colocalizes with EGFR. Costaining with an Ab against phosphorylated ERK5 in addition to fluorescently labeled EGF is used to show the relationship between EGFR and activated ERK5. (Scale bar, 20 μM.)

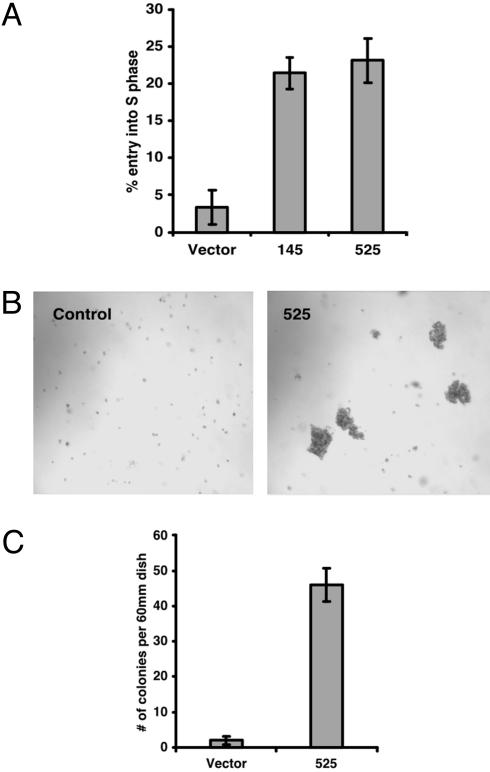

Down-Regulation of GAK Leads to Cell Proliferation and Partial Transformation. The large changes in receptor abundance, localization, and function occasioned by down-regulation of GAK might be expected to have biological consequences. We first examined HeLa cell entry into S phase under serum starvation by measuring the number of cells incorporating BrdUrd into DNA. Approximately 20% of GAK knockdown cells were BrdUrd-positive as compared with ≈3.4% of vector control cells (Fig. 5A). Thus, down-regulation of GAK exerts a significant biological effect by promoting cell proliferation in the absence of growth factors. To determine whether knocking down GAK expression would cause cell transformation, we used RNAi to down-regulate GAK in CV1P cells because HeLa cells are already transformed. Fig. 5 B and C show that knocking down GAK results in a marked increase in soft agar colony formation by using CV1P cells. Notably, the colonies seen are smaller than would be seen in fully transformed cells cultured for the same period.

Fig. 5.

Down-regulation of GAK promotes cell proliferation and cell transformation. (A) Down-regulation of GAK promotes cell proliferation under conditions of serum starvation. Cells grown on chamber slides were serumstarved overnight and labeled with BrdUrd for 15 h. Cells were fixed and incubated with an Ab against BrdUrd. BrdUrd-positive cells were counted among DAPI-stained cells in at least 10 randomly selected fields on each slide (n = 3). (B) Down-regulation of GAK transforms CV1P cells. CV1P cells (vector control and 525) were seeded in soft agar. Phase-contrast image of the colonies from a representative experiment is shown (magnification: ×7). (C) Colony numbers (colony with >50 cells) from B were counted at 21 days after cells were seeded (n = 3).

Discussion

The data presented here reveal an unexpected effect of GAK on receptor signaling, suggesting that GAK is involved in considerably more than regulating the formation and uncoating of clathrin-coated vesicles. If GAK were required for assembly of coated vesicles, we would have expected to see receptor trafficking block near the cell surface. Similarly, if GAK were simply required for uncoating, we might have expected to see EGFR trafficking blocked in clathrin-coated vesicles. In the GAK knockdown cells, receptors are found in structures containing both clathrin and early endosomal markers. This finding suggests that loss of GAK impairs the uncoating process and results in clathrin being present on vesicles from which it would normally have been stripped. However, our data further suggest that GAK plays an active role in trafficking downstream of clathrin-coated vesicles in regulating the correct functioning of the endosome. This finding is implied by the fact that the receptors apparently are trapped not at the uncoating stage but in the endosome itself. More importantly, the endosome appears to be altered in the knockdown cells even in the absence of EGF stimulation, indicating that GAK plays an important role in the normal ontogeny of the endosome.

How can we model the effects of down-regulating GAK on signaling? It is reasonable to suppose that both the increased receptor numbers and alterations in receptor signaling result at least in part from an underlying defect in receptor trafficking. The increase in numbers may simply reflect the fact that the normal degradation of the receptor in the lysosome is blocked. The signaling defect is perhaps more interesting. We wondered whether it might simply result from the increased numbers of receptors but this possibility seems unlikely for two reasons. First, in our transient experiments with GAK siRNA, we sometimes see lower levels of receptor expression but the same effects on the early endosome. Second, we checked A431 cells and found that, although they feature even higher numbers of EGFR, they did not display the alterations of the EGFR signaling reported here. It seems more likely that the altered signaling results from the fact that the receptors transit through trafficking compartments such as the early endosome extremely slowly. We note the similarity to data reported for the Trk family of receptors (33). When Trks are activated on the cell body they signal through ERK1/2. When they are activated in a long axon and take part in a prolonged journey to the cell body, ERK5 signaling is seen. We hope that with further experimentation we may find that the signaling intermediates generated in GAK knockdown cells will give us useful information on normal signaling.

Our results differ significantly from those of Vieira et al. (25) who observed that overexpression of dominant-negative dynamin inhibits EGFR-mediated ERK activation. Part of the differences between the effects of dominant-negative dynamin and GAK down-regulation might lie in the technical details of the two studies. Vieira et al. (25) measured EGFR signaling in HeLa cells treated with 3.5 nM EGF, whereas we are using a somewhat higher EGF concentration (8 nM). At lower levels of EGF, internalization of EGFR has been reported to occur solely through clathrin-coated vesicles, while at higher concentrations, other pathways have been reported to be operative (34). However, we have repeated our work at 4 nM EGF and observed similar effects on Erk1/2 activation as displayed in Fig. 3A (data not shown). Notably, other workers have reported that even at an EGF concentration of 10–12 M, dominant-negative dynamin does not block ERK activation (35). We think that it is likely that the major cause of differences between our data and earlier reports with dominant-negative dynamin stem from intrinsic differences between the roles of GAK and dynamin in EGFR internalization.

Most of the data shown here were obtained from HeLa cells in which GAK had been stably depleted by means of retroviral expression of small hairpin RNA to GAK. It is fair to ask whether some of the effects observed might arise secondarily in the course of long term culture. Certainly, such indirect effects of GAK depletion can occur. For instance, we know that GAK depletion by transient transfection of GAK siRNA blocks transferrin uptake, whereas cells in which GAK is stably depleted show only minor inhibition of transferrin uptake (data not shown). This effect presumably is selected for because transferrin is required for long-term survival of the cells. We have also observed that, whereas stable GAK depletion certainly causes an increase in EGFR stability as expected, it also results in an approximately 10-fold increase in the levels of mRNA for EGFR (data not shown). Thus, it is possible that some of the quantitative effects we see in EGFR levels arise secondarily. However, we would like to stress that all of the qualitative changes reported here (increased levels of EGFR protein and signaling, increased activation of ERK5, and changes in localization of EEA1) all occur in cells where GAK has been acutely depleted via transfection of siRNA oligos.

Various molecular mechanisms might underlie the observed changes in EGFR trafficking and signaling. For example, the depletion of GAK's auxilin-like activity would be expected to play a significant role in the apparent defects in clathrin uncoating. In addition the Cbl-mediated EGFR degradation pathway might be altered in GAK knockdown cells. Cbl consists of an N-terminal phosphotyrosine binding domain and a C-terminal proline-rich domain separated by a zinc-RING finger motif (36, 37). Cbl has been reported to bind to various signaling proteins, including the EGFR through its phosphotyrosine binding domain, and subsequently bring about their ubiquitination by means of the zinc-Ring finger motif (36, 37). Overexpression of Cbl promotes down-regulation of EGFR through receptor ubiquitination (38, 39). In GAK knockdown cells, c-Cbl is significantly down-regulated (data not shown). It seems likely that GAK is affecting the stability of c-Cbl, either through direct phosphorylation or through some more indirect route. GAK is also known to phosphorylate μ subunits of AP1 and AP2 in vitro (4, 9). If AP1 and AP2 are also targets of GAK in vivo, this phosphorylation might also contribute to the effects reported here. Potential effects of GAK on AP1 in particular might play a role in the effects of depleting GAK on trafficking steps distal from the membrane. Obviously other key targets for GAK may play a role in EGFR signaling. Further work will be required to delineate GAK targets in vivo.

GAK down-regulation might be expected to have effects on the internalization and signaling of other receptors as well. We have found that the effects of GAK down-regulation vary from receptor to receptor and also vary with the cell type being studied. To date, only the EGFR has been dramatically up-regulated by GAK depletion in multiple cell types. Many receptors are unaffected. For instance, in HeLa cells, neither HER2 nor IGF receptor up-regulation is observed upon GAK knockdown. Similarly, in NIH 3T3 cells, we have seen no effects on PDGF receptor after GAK knockdown. The function of receptors outside the class of receptor tyrosine kinases has even been observed to be impaired (data not shown). Even the effects that we see on EGFR in HeLa, CV1P, and COS-7 cells are not seen in all cell types. It is well known that signal transduction of various receptors varies with cell type. Therefore, it is perhaps not surprising to see different results in receptor trafficking in different cell types.

Finally, the fact that GAK down-regulation can result in enhanced soft agar growth suggests GAK may function as a tumor suppressor. Whereas the level of soft agar growth that we see in CV1P cells depleted of GAK is relatively modest, the effect of GAK loss could easily be imagined to synergize with other mutations to facilitate tumor growth. Interestingly, the GAK chromosomal locus 4p16.3 has been found to show loss of heterozygosity in multiple tumor types, including breast and colon cell carcinomas (40, 41). A more detailed analysis of the GAK gene in these and other tumors could be a target for future work.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Scott Pomeroy and Matthew C. Salanga for expert technical assistance in obtaining confocal microscope images; and Drs. Charles D. Stiles, Pamela A. Silver, Bruce Spiegelman, Sanja Sever, Helen McNamee, Joanne Chan, Danielle K. Lynch, and Grace Williams for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants CA50661 (to T.M.R.) and P30 HD18655 (to Scott Pomeroy).

Abbreviations: GAK, cyclin G-associated kinase; EGF, epidermal growth factor; EGFR, EGF receptor; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; Hsc70, heat shock cognate 70; RNAi, RNA interference; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; AP, adaptor protein.

References

- 1.Kanaoka, Y., Kimura, S. H., Okazaki, I., Ikeda, M. & Nojima, H. (1997) FEBS Lett. 402, 73–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kimura, S. H., Tsuruga, H., Yabuta, N., Endo, Y. & Nojima, H. (1997) Genomics 44, 179–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greener, T., Zhao, X., Nojima, H., Eisenberg, E. & Greene, L. E. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 1365–1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Umeda, A., Meyerholz, A. & Ungewickell, E. (2000) Eur. J. Cell Biol. 79, 336–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Korolchuk, V. I. & Banting, G. (2002) Traffic 3, 428–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conner, S. D. & Schmid, S. L. (2002) J. Cell Biol. 156, 921–929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conner, S. D. & Schmid, S. L. (2003) J. Cell Biol. 162, 773–779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Conner, S. D., Schroter, T. & Schmid, S. L. (2003) Traffic 4, 885–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ricotta, D., Conner, S. D., Schmid, S. L., von Figura, K. & Honing, S. (2002) J. Cell Biol. 156, 791–795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhao, X., Greener, T., Al-Hasani, H., Cushman, S. W., Eisenberg, E. & Greene, L. E. (2001) J. Cell Sci. 114, 353–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schlessinger, J. (2000) Cell 103, 211–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pawson, T. & Hunter, T. (1994) Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 4, 1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benveniste, M., Schlessinger, J. & Kam, Z. (1989) J. Cell Biol. 109, 2105–2115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schlessinger, J., Schreiber, A. B., Levi, A., Lax, I., Libermann, T. & Yarden, Y. (1983) CRC Crit. Rev. Biochem. 14, 93–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schreiber, A. B., Libermann, T. A., Lax, I., Yarden, Y. & Schlessinger, J. (1983) J. Biol. Chem. 258, 846–853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sorkin, A. (1998) Front. Biosci. 3, D729–D738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robinson, M. J. & Cobb, M. H. (1997) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 9, 180–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morrison, D. K., Kaplan, D. R., Rapp, U. & Roberts, T. M. (1988) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85, 8855–8859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williams, N. G., Paradis, H., Agarwal, S., Charest, D. L., Pelech, S. L. & Roberts, T. M. (1993) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90, 5772–5776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mason, C. S., Springer, C. J., Cooper, R. G., Superti-Furga, G., Marshall, C. J. & Marais, R. (1999) EMBO J. 18, 2137–2148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hindley, A. & Kolch, W. (2002) J. Cell Sci. 115, 1575–1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fruman, D. A., Meyers, R. E. & Cantley, L. C. (1998) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67, 481–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cantley, L. C. (2002) Science 296, 1655–1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klippel, A., Kavanaugh, W. M., Pot, D. & Williams, L. T. (1997) Mol. Cell. Biol. 17, 338–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vieira, A. V., Lamaze, C. & Schmid, S. L. (1996) Science 274, 2086–2089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brummelkamp, T. R., Bernards, R. & Agami, R. (2002) Cancer Cell 2, 243–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levy-Toledano, R., Caro, L. H., Hindman, N. & Taylor, S. I. (1993) Endocrinology 133, 1803–1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lokeshwar, V. B., Huang, S. S. & Huang, J. S. (1989) J. Biol. Chem. 264, 19318–19326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wiley, H. S. (2003) Exp. Cell Res. 284, 78–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abe, J., Kusuhara, M., Ulevitch, R. J., Berk, B. C. & Lee, J. D. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 16586–16590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kato, Y., Tapping, R. I., Huang, S., Watson, M. H., Ulevitch, R. J. & Lee, J. D. (1998) Nature 395, 713–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.English, J. M., Pearson, G., Hockenberry, T., Shivakumar, L., White, M. A. & Cobb, M. H. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 31588–31592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Watson, F. L., Heerssen, H. M., Bhattacharyya, A., Klesse, L., Lin, M. Z. & Segal, R. A. (2001) Nat. Neurosci. 4, 981–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sorkin, A., McClure, M., Huang, F. & Carter, R. (2000) Curr. Biol. 10, 1395–1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johannessen, L. E., Ringerike, T., Molnes, J. & Madshus, I. H. (2000) Exp. Cell Res. 260, 136–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thien, C. B. & Langdon, W. Y. (2001) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2, 294–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sanjay, A., Horne, W. C. & Baron, R. (2001) Sci. STKE 2001, PE40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dikic, I. (2003) Biochem. Soc. Trans. 31, 1178–1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yokouchi, M., Kondo, T., Houghton, A., Bartkiewicz, M., Horne, W. C., Zhang, H., Yoshimura, A. & Baron, R. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 31707–31712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shivapurkar, N., Maitra, A., Milchgrub, S. & Gazdar, A. F. (2001) Hum. Pathol. 32, 169–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shivapurkar, N., Sood, S., Wistuba, I. I., Virmani, A. K., Maitra, A., Milchgrub, S., Minna, J. D. & Gazdar, A. F. (1999) Cancer Res. 59, 3576–3580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]