Abstract

Purpose:

To compare the effects of bevacizumab and ranibizumab on the visual function and macular thickness in the contralateral (untreated) eye of patients with bilateral diabetic macular edema (DME).

Materials and Methods:

Thirty-nine patients with bilateral DME, who had been treated with both bevacizumab and ranibizumab in the same eye, were considered retrospectively for this study. Recorded outcome measurements included the best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) assessment with the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) chart and the central subfield macular thickness (CSMT) measurement of the contralateral, uninjected eye before and at 4 weeks after the injections.

Results:

The median BCVA of the uninjected eye was 50 ETDRS letters and the median CSMT was 459 μm preceding the bevacizumab injection whereas at the control appointment, 4 weeks after the injection, the median BCVA had increased to 52 letters (P = 0.098), and the median CSMT had decreased to 390 μm (P = 0.036). The mean interval between the bevacizumab and ranibizumab treatments was 4.79 1.52 months. The measurements of the untreated eye after the ranibizumab treatment showed that the median BCVA decreased from 55 to 52 letters, and the median CSMT increased from 361 μm to 418 μm (P = 0.148 and P = 0.109, respectively).

Conclusions:

In contrast to ranibizumab, the intravitreal administration of bevacizumab resulted in a statistically significant decrease in macular thickness in the untreated eye in patients with bilateral DME.

Keywords: Antivascular endothelial growth factor treatment, bevacizumab, diabetic retinopathy, macular edema, ranibizumab

Introduction

One of the main causes of loss of vision in patients diagnosed with diabetes is the development of diabetic macular edema (DME).[1,2] DME is associated with high levels of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in the vitreous humor.[3] Recent research studies have focused on anti-VEGF medications for the treatment of DME; bevacizumab (Avastin) (Genentech, San Francisco, CA, USA) and ranibizumab (Lucentis) (Genentech, San Francisco, CA, USA) are the two most widely used VEGF inhibitors.[3,4,5,6] Bevacizumab is a full-length antibody of 149 kDa that binds to all subtypes of the VEGF-A. On the other hand, ranibizumab is an antigen-binding (Fab) fragment of a humanized monoclonal antibody with a molecular weight of 48 kDa that also binds all the isoforms of VEGF-A.[2,3] The differences in the molecular weight and structure of bevacizumab and ranibizumab influence their penetration, half-lives, and efficacy.

The plasma levels of VEGF in patients were found to be significantly reduced after the intravitreal injection of bevacizumab.[7,8] This finding suggested that the body clears anti-VEGF after intravitreal administration, which prompts the question of whether or not there is an effect on the contralateral eye after intravitreal use. However, there are few studies regarding the pharmacokinetics and distribution of these agents after intravitreal injection, particularly in human eyes.

In a pilot study, the intravitreal administration of bevacizumab was found to have no significant effect on the contralateral eye in patients with bilateral DME.[9] However, in some cases with macular edema, an effect on the contralateral eye has been observed after this intravitreal anti-VEGF injection.[10,11,12,13] Since the pharmacokinetic properties of an intravitreally administered drug and the function of the blood-retinal barrier may vary from one person to another (and may change in the presence of ocular disease), it is difficult to assess and compare the crossover effect of these two agents when used intravitreally. Therefore, we performed this study to compare the visual and structural outcomes on the contralateral, uninjected eye after one intravitreal injection of bevacizumab and one of ranibizumab to the treated (same) eye of patients with bilateral DME at selected points in time.

Materials and Methods

This retrospective review was carried out on patients who were in the follow-up stage of a diagnosis of DME at the retina clinic. Data was collected from January 2012 to April 2013, and patients with bilateral DME who received a single dose (injection) of bevacizumab and who did not attend the scheduled repeat intravitreal bevacizumab injections were considered for enrollment. Among them, patients who visited the retina clinic after at least 3 months and who planned to receive monthly intravitreal ranibizumab injections for their DME were included in the study. The Local Ethics Committee approved this study, which was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Exclusion criteria were (a) those with a history or evidence of a macular pathology such as age-related macular degeneration (ARMD) or a vascular occlusive disease affecting the macula, (b) treatment with any other intravitreal drug injections or laser photocoagulation within 3 months (previously) to either eye, (c) any associated pathology such as an epiretinal membrane or vitreomacular traction, or (d) any history of retinal surgery.

Intravitreal injection protocol for ranibizumab and bevacizumab injections

The exclusion criteria for the injections of ranibizumab and bevacizumab included any history of myocardial infarction or cerebrovascular incident, evidence of a severe cardiac disease, a history of stroke, a history of a chronic ocular or periocular infection, uncontrolled hypertension, or pregnancy. Intravitreal injections were performed at the same institution by the same ophthalmologists (Berker Bakbak, Banu Turgut Ozturk). Using a sterile lid speculum, 1.25 mg (0.05 mL) of bevacizumab was injected through the pars plana. In the second injection time, 0.5 mg (0.05 mL) of ranibizumab was injected through the pars plana.

Outcomes

The preinjection best-corrected visual acuities (BCVAs) were determined using the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) chart (at 4 m and 1 m), intraocular pressure (IOP) measurements, slit lamp and fundus examination findings, and central subfield macular thickness (CSMT) measurements using time domain optical coherence tomography (OCT, Carl Zeiss Meditec, San Leandro, CA, USA). The examination findings during the control visits after 1 day and 4 weeks following the injections were reviewed as well. The first visit was done to assess any complications and included IOP measurements with an air-puff tonometer, a slit-lamp examination, and a dilated fundus examination. During the second visit, the BCVA and OCT measurements were also performed. The primary outcome variables included any BCVA and CSMT changes in either eye after the bevacizumab and ranibizumab injections.

Statistical analysis

A statistical analysis was carried out using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) program (15.0, Windows) (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The visual acuities and CSMT values were compared using the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U-test and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. A probability (P) value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A review of all of the patients with DME who met the inclusion criteria yielded a total of 39 patients. The mean age of these 39 patients (16 males and 23 females; 41.1% and 58.9%, respectively) was 56.9 ± 11.58 years old. Five patients had type 1 diabetes mellitus (DM), and the remaining 34 were diagnosed with type 2 DM.

Eleven patients (28.2%) exhibited nephropathy as a DM-related complication, and 25 patients (64.1%) had controlled hypertension. The diabetic retinopathy was in the preproliferative stage in 21 of the patients (53.8%).

No complications, including issues such as endophthalmitis, traumatic lens injury, raised IOP, or retinal detachment, were associated with the intravitreal injections. Before the bevacizumab injection, the median (baseline) BCVA for the treated eyes was 48 (18–68) ETDRS letters, which increased to 52 (18–76) ETDRS letters after the injections. The median CSMT of 473 (297–682) μm before the bevacizumab injection decreased to 337 (249–566) μm after the treatment. These changes in the BCVA and CSMT in the eyes treated with bevacizumab were found to be statistically significant (P = 0.029 and P = 0.005, respectively).

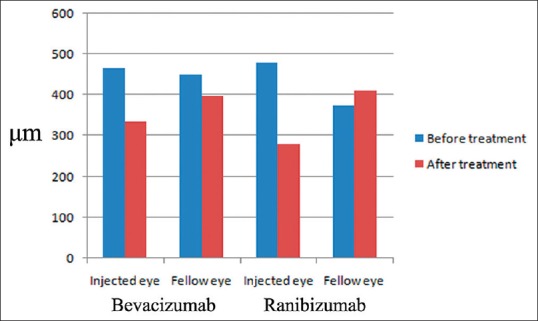

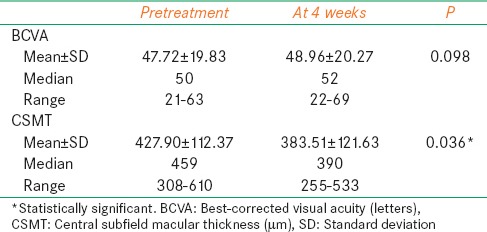

In the uninjected (fellow) eyes, the median BCVA was 50 (21–63) ETDRS letters and the median CSMT was 459 (308–610) μm preceding the bevacizumab injection. At the 4th week control follow-up after the injection, the median BCVA had increased to 52 (22–69) ETDRS letters, and the median CSMT had decreased to 390 (255–533) μm. There was no statistically significant change in the BCVA (P = 0.098); however, the decrease in the CSMT was found to be statistically significant at P = 0.036 [Figure 1 and Table 1].

Figure 1.

A comparison of the changes in the macular thickness in treated and untreated eyes of the same patients, before (baseline) and at 4 weeks after the intravitreal bevacizumab and ranibizumab injections. Note that a statistically significant decrease in the central subfield macular thickness was seen with the bevacizumab administration, but not with the ranibizumab. μm: Microns

Table 1.

Visual acuity and CSMT values of untreated eyes before and after bevacizumab injection

Intravitreal ranibizumab was administered to the same eye after a mean period of 4.79 ± 1.52 (3–6) months. In the treated eye, the pretreatment median BCVA of 46 (20–73) ETDRS letters increased to 53 (22–78) ETDRS letters after the treatment, and the preinjection median CSMT of 483 (298–670) μm declined to a level of 265 (214–563) μm after the treatment. Statistical analyses revealed significant changes in both the BCVA and CSMT (P = 0.008 and P < 0.001, respectively).

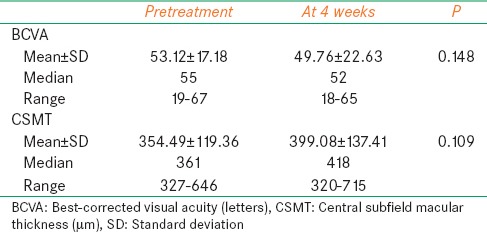

The measurements of the untreated (fellow) eye after the ranibizumab treatment showed that the median BCVA decreased from 55 (19–67) to 52 (18–65) ETDRS letters, and the median CSMT increased from 361 (327–646) μm to a level of 418 (320–715) μm. The changes in the BCVA and CSMT were found to be statistically insignificant (P = 0.148 and P = 0.109, respectively) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Visual acuity and CSMT values of untreated eyes before and after ranibizumab injection

Discussion

VEGF plays a key role in the pathogenesis of DME.[5,6,14] Several reviews have been conducted on the efficacy of the two anti-VEGFs, bevacizumab and ranibizumab, in the treatment of DME.[1,2,3,5] Bevacizumab is a full-length humanized antibody that binds all types of VEGF-A. It is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of various cancers, but it is used off-label intravitreally to treat ocular diseases, including proliferative diabetic retinopathy and DME. Ranibizumab, a recombinant humanized monoclonal IgG1 antibody, is approved for choroidal neovascularization in the context of ARMD and DME. Despite their widespread clinical applications, the pharmacokinetics of intravitreal bevacizumab and ranibizumab concerning untreated eyes has not been extensively studied.

In the present study, we found a statistically significant decrease in the CSMT in untreated eyes after the injection of bevacizumab but not after ranibizumab. This finding suggests that there is a systemic penetration of bevacizumab from human eye injections, and it supports a previous study that demonstrated a significant reduction in plasma VEGF after an intravitreal injection with bevacizumab but not ranibizumab.[7,8]

In an experimental study, Bakri et al.[15] found small amounts of bevacizumab in the serum and in the (fellow) uninjected eye. Avery et al.[12] reported that some of their patients with bilateral proliferative diabetic retinopathy had a regression of neovascularization in both eyes when injected with intravitreal bevacizumab in only one eye. Similar results were observed after unilateral intravitreal bevacizumab injections in the cases of bilateral persistent diffuse DME or bilateral uveitic cystoid macular edema.[11,16] A pilot study on bilateral DME suggested no significant effects in the contralateral, uninjected eye; however, the researchers emphasized the small sample size and low confidence in their own study.[9] In addition to all, Sharma et al. found that an intravitreal dexamethasone injection seems to have bilateral effect after unilateral injection, which pointed out the effect of unilateral intravitreal injection on the fellow eye.[17]

In this study, intravitreal ranibizumab administration in patients with DME was found to produce no statistically significant change in the BCVA and CSMT in the contralateral (uninjected) eye. We also compared these results (in which a statistically significant decrease in CSMT was found) to those for the untreated eyes after the treatment with bevacizumab in the same patients.

There are conflicting results in the literature regarding the contralateral eye effects of intravitreal ranibizumab injections. A retrospective observational study has demonstrated a visual improvement in the contralateral eyes of patients with ARMD after intravitreal ranibizumab injection.[18] Acharya et al.[13] observed the beneficial effect of ranibizumab in both eyes of patients (two of three patients) who were treated unilaterally for uveitis-related CME. However, Bakri et al.[19] found no ranibizumab in either the serum or the fellow uninjected eye after a 0.5 mg intravitreal injection. Similarly, Gamulescu and Helbig observed no therapeutic effect of ranibizumab in the untreated fellow eye in patients with ARMD.[20] A Phase III clinical trial of ranibizumab for ARMD also showed no effect on the rate of choroidal neovascularization development in the untreated eyes.[21]

We are unaware of any previous studies that have evaluated a crossover effect (in the eye contralateral to the treatment eye) of bevacizumab and ranibizumab in patients with bilateral DME. The effects of both agents in the treated eyes of our patients support the previous studies in which bevacizumab and ranibizumab effectively reduced the macular thickness and improved the visual acuity in the treated eyes.[1,2,3] However, this result raises the question of why only bevacizumab administration affected the untreated eye. The exact mechanism of how intravitreally administered anti-VEGFs affect an uninjected eye has not been elucidated thus far. One possible mechanism for this is that the anti-VEGF enters the bloodstream via the choroidal blood flow.[12,13] In contrast, other researchers have suggested that bevacizumab enters the eye from the systemic circulation through the anterior route, where it diffuses into the vitreous humor.[9] Ranibizumab has a smaller molecular weight when compared with bevacizumab, so it is possible that it may pass to the fellow eye more easily. However, experimental studies using rabbits have demonstrated that no ranibizumab was detected in the serum or the fellow eye, whereas bevacizumab was found in both the serum and the fellow eye.[15,19] Nevertheless, the rabbit retina is less vascular than a human's, which may result in altered pharmacokinetics when compared with the human condition. Another reason that bevacizumab might have a contralateral effect while ranibizumab does not concern the systemic half-lives of the two drugs. A longer half-life increases the exposure in the contralateral eye, improves penetration, and enables a possible clinical effect.

Aflibercept, also known as VEGF-Trap eye, is a soluble fusion protein that binds all isoforms of VEGF-A and VEGF-B as well as placental growth factor.[22] Intravitreal injection of 2 mg of aflibercept is currently approved for the treatment of DME. Due to the molecular structure of aflibercept, it has a prolonged intravitreal half-life.[23] In a study comparing serum pharmacokinetics of three anti-VEGFs, bevacizumab and aflibercept demonstrated greater systemic exposure and produced a marked reduction in plasma-free VEGF in comparison to ranibizumab, which was quickly cleared.[23]

Our study has some limitations. Since ranibizumab has a shorter lifetime than bevacizumab, it is possible that the effect of ranibizumab may have decreased by the 4-week follow-up. Therefore, a 2nd -week visit including OCT measurement should be performed to achieve an equitable assessment. In addition, for a proper comparison of the two anti-VEGFs, HbA1c levels should have been obtained prior to both the bevacizumab and the ranibizumab injection to see whether any change was present.

Our previous study using 55 patients with bilateral DME demonstrated that compared with ranibizumab, the intravitreal administration of bevacizumab resulted in a greater decrease in the macular thickness of the untreated eye in patients with bilateral DME.[24] However, in that study, we administered either bevacizumab or ranibizumab to two different groups of patients. Since the pharmacokinetic properties of an intravitreally administered anti-VEGF and the blood-retinal barrier function may vary from one person to another and change in the presence of an ocular disease, we compared the crossover effect of the agents in the same patients for this study. Further investigation, including the analysis of the serum and vitreous levels of the anti-VEGF agents, will be the best study design for the comparison.

In summary, we found that in contrast to ranibizumab, the intravitreal administration of bevacizumab resulted in a statistically significant decrease in the macular thickness of the untreated eye in patients with bilateral DME.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Ford JA, Elders A, Shyangdan D, Royle P, Waugh N. The relative clinical effectiveness of ranibizumab and bevacizumab in diabetic macular oedema: An indirect comparison in a systematic review. BMJ. 2012;345:e5182. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zechmeister-Koss I, Huic M. Vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors (anti-VEGF) in the management of diabetic macular oedema: A systematic review. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012;96:167–78. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-300674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ozturk BT, Kerimoglu H, Bozkurt B, Okudan S. Comparison of intravitreal bevacizumab and ranibizumab treatment for diabetic macular edema. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2011;27:373–7. doi: 10.1089/jop.2010.0195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goyal S, Lavalley M, Subramanian ML. Meta-analysis and review on the effect of bevacizumab in diabetic macular edema. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2011;249:15–27. doi: 10.1007/s00417-010-1452-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singh R, Ramasamy K, Abraham C, Gupta V, Gupta A. Diabetic retinopathy: An update. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2008;56:178–88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chun DW, Heier JS, Topping TM, Duker JS, Bankert JM. A pilot study of multiple intravitreal injections of ranibizumab in patients with center-involving clinically significant diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:1706–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carneiro AM, Costa R, Falcão MS, Barthelmes D, Mendonça LS, Fonseca SL, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor plasma levels before and after treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration with bevacizumab or ranibizumab. Acta Ophthalmol. 2012;90:e25–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2011.02240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zehetner C, Kirchmair R, Huber S, Kralinger MT, Kieselbach GF. Plasma levels of vascular endothelial growth factor before and after intravitreal injection of bevacizumab, ranibizumab and pegaptanib in patients with age-related macular degeneration, and in patients with diabetic macular oedema. Br J Ophthalmol. 2013;97:454–9. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2012-302451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Velez-Montoya R, Fromow-Guerra J, Burgos O, Landers MB 3 r rd, Morales-Catón V, Quiroz-Mercado H. The effect of unilateral intravitreal bevacizumab (avastin), in the treatment of diffuse bilateral diabetic macular edema: A pilot study. Retina. 2009;29:20–6. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e318186c64e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu Z, Sadda SR. Effects on the contralateral eye after intravitreal bevacizumab and ranibizumab injections: A case report. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2008;37:591–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al-Dhibi H, Khan AO. Bilateral response following unilateral intravitreal bevacizumab injection in a child with uveitic cystoid macular edema. J AAPOS. 2009;13:400–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Avery RL, Pearlman J, Pieramici DJ, Rabena MD, Castellarin AA, Nasir MA, et al. Intravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin) in the treatment of proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:1695.e1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.05.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Acharya NR, Sittivarakul W, Qian Y, Hong KC, Lee SM. Bilateral effect of unilateral ranibizumab in patients with uveitis-related macular edema. Retina. 2011;31:1871–6. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e318213da43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Selim KM, Sahan D, Muhittin T, Osman C, Mustafa O. Increased levels of vascular endothelial growth factor in the aqueous humor of patients with diabetic retinopathy. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2010;58:375–9. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.67042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bakri SJ, Snyder MR, Reid JM, Pulido JS, Singh RJ. Pharmacokinetics of intravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin) Ophthalmology. 2007;114:855–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scartozzi R, Chao JR, Walsh AC, Eliott D. Bilateral improvement of persistent diffuse diabetic macular oedema after unilateral intravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin) injection. Eye (Lond) 2009;23:1229. doi: 10.1038/eye.2008.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharma A, Sheth J, Madhusudan RJ, Sundaramoorthy SK. Effect of intravitreal dexamethasone implant on the contralateral eye: A case report. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2013;7:217–9. doi: 10.1097/ICB.0b013e31828993a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rouvas A, Liarakos VS, Theodossiadis P, Papathanassiou M, Petrou P, Ladas I, et al. The effect of intravitreal ranibizumab on the fellow untreated eye with subfoveal scarring due to exudative age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmologica. 2009;223:383–9. doi: 10.1159/000228590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bakri SJ, Snyder MR, Reid JM, Pulido JS, Ezzat MK, Singh RJ. Pharmacokinetics of intravitreal ranibizumab (Lucentis) Ophthalmology. 2007;114:2179–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gamulescu MA, Helbig H. Lack of therapeutic effect of ranibizumab in fellow eyes after intravitreal administration. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2010;26:213–6. doi: 10.1089/jop.2009.0126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barbazetto IA, Saroj N, Shapiro H, Wong P, Ho AC, Freund KB. Incidence of new choroidal neovascularization in fellow eyes of patients treated in the MARINA and ANCHOR trials. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;149:939–946.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2010.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martin DF, Maguire MG. Treatment choice for diabetic macular edema. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1260–1. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1500351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Avery RL, Castellarin AA, Steinle NC, Dhoot DS, Pieramici DJ, See R, et al. Systemic pharmacokinetics following intravitreal injections of ranibizumab, bevacizumab or aflibercept in patients with neovascular AMD. Br J Ophthalmol. 2014;98:1636–41. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2014-305252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bakbak B, Ozturk BT, Gonul S, Yilmaz M, Gedik S. Comparison of the effect of unilateral intravitreal bevacizumab and ranibizumab injection on diabetic macular edema of the fellow eye. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2013;29:728–32. doi: 10.1089/jop.2013.0049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]