Abstract

Background:

The sensitivity of cervical cytology for detection of glandular lesions is reported to be low. We conducted this study to assess the diagnostic accuracy of cervical Papanicolaou (Pap) smears for uterine glandular lesions and to compare the diagnostic utility of conventional and liquid-based cytology (LBC) smears for glandular lesions.

Materials and Methods:

Archived histopathology records of all cases reported as endocervical and endometrial adenocarcinoma in the study period were identified and the available corresponding Pap smears (in preceding 1 year) were retrieved. In addition, the Pap smears reported as glandular cell abnormalities (GCA) during the same study period were retrieved. The overall prevalence of GCA, sensitivity, and specificity of Pap smears for the detection of GCA was calculated. The diagnostic accuracy of conventional and LBC smears for the diagnosis of GCA was also compared.

Results:

The prevalence of GCA in our study was 0.32%. The overall specificity of Pap smears for the diagnosis of GCA was 60.8%, this was not significantly different between conventional and LBC smears (P = 0.4). The overall sensitivity of Pap smears for the detection of GCA was 41.8%; LBC smears had significantly better sensitivity as compared to conventional smears for the detection of endometrial as compared to endocervical adenocarcinoma (P < 0.05).

Conclusions:

The prevalence of GCA in Pap smears is low. The specificity of Pap smears, for diagnosis of GCA, was found to be moderate. However, the overall sensitivity of Pap smears for the detection of GCA was low, though better for LBC as compared to conventional smears.

Keywords: Endocervical adenocarcinoma, endometrial adenocarcinoma, glandular lesions, liquid-based cytology, Papanicolaou smears

INTRODUCTION

Cervical cytology by Papanicolaou (Pap) smears is perhaps the most successful cancer-screening test developed to-date. It not only helps in achieving a rapid and early diagnosis of cervical cancer, but also leads to a significant reduction in morbidity and mortality. Pap smears have a high sensitivity for the detection of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and its precursor lesions.[1] This has led to a substantial decrease in the overall incidence of cervical SCC. However, glandular lesions on Pap smears pose a greater diagnostic challenge to cytopathologists, with low reported sensitivity rates.[2] The major hurdles to accurate cytodiagnosis are lesser representation of the glandular lesions on Pap smears and the well-known look-alikes of glandular lesions, which often lead to false positive diagnosis.[3,4]

Although glandular cells are often seen on Pap smears, glandular cell abnormalities (GCA) are reported in only a very small fraction (<1%) of all the routine Pap smears. This low rate notwithstanding, clinically significant lesions have been reported in 18–83% of patients with GCA detected on Pap smears.[5,6,7,8,9] Thus, it is extremely important to correctly identify GCA on Pap smears, followed by immediate colposcopic assessment and fractional curettage.

Following the development of liquid-based cytology (LBC), the sensitivity of Pap smears for the detection of GCA has improved. This is mainly due to better sampling, complete transfer of cells into the liquid medium, lesser obscuration by blood and inflammatory cells, and better preservation and visualization of even few scattered abnormal cells.[10,11,12]

Therefore, the present study was undertaken to assess the utility of Pap smears in cytodiagnosis of uterine glandular lesions.

Aims and objectives

Primary objective: To assess the diagnostic accuracy of cervical Pap smears for uterine glandular lesions

Secondary objective: To compare the diagnostic accuracy of conventional and liquid-based cervical samples for uterine glandular lesions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

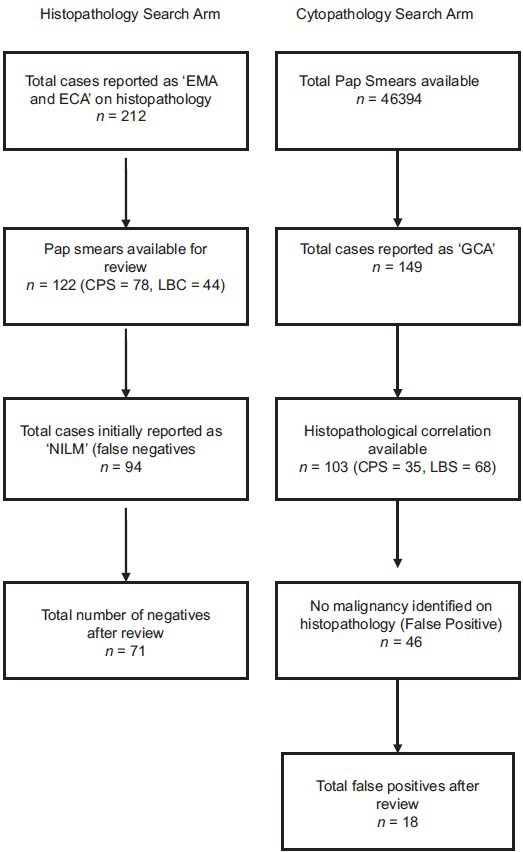

This was a retrospective study, conducted over a period of 3 years (2012–2014) in the Department of Cytology and Gynecologic Pathology at a tertiary care institute. A two-pronged search strategy was adopted [Figure 1]:

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing search methodology adopted in the study

The “histopathology search” arm: Archived histopathology records of all cases reported as endometrial adenocarcinoma (EMA) or endocervical adenocarcinoma (ECA) within the study period were identified and their corresponding Pap smears, if available within preceding 1 year of the diagnosis, were retrieved

The “cytopathology search” arm: Archived records of all Pap smears reported during the study period were searched for GCA and the Pap smears of such cases were retrieved.

Inclusion criteria

From the histopathology search arm, Pap smears (both conventional and LBC) of cases reported as EMA or ECA were included

From the cytopathology search arm, Pap smears (conventional and LBC), reported as GCA, including atypical glandular cells – not otherwise specified (AGC-NOS), AGC – favor neoplasm (AGC-FN), EMA, and ECA were included.

Exclusion criteria

Pap smears reported as negative for any intraepithelial lesion or malignancy (NILM) in the cytopathology search arm, unsatisfactory smears or those with glandular or squamous epithelial cell abnormality, but without a follow-up histopathological diagnosis were excluded.

Analysis of smears

From the cytopathology search arm, all included Pap smear reports were analyzed against their histopathology report to know the cytology-histopathology correlation. Similarly, from the histopathology search arm, all included cases of malignancy reports were analyzed against their corresponding Pap smear reports. Discordant cases from both search arms were then reviewed together by two cytopathologists, keeping in mind the histological diagnosis, to see if a revised cytological diagnosis could be offered. GCA negative cases, which were positive for malignancy, were reviewed as per The Bethesda System (TBS) 2001 guidelines.

Outcome measures

The following outcome measures were studied:

Prevalence of GCA: Calculated as a percentage of total number of Pap smears reported as having GCA, divided by the total number of Pap smears reported in the study period

“True positive” smear: A Pap smear was labeled as true positive if it was reported as GCA and the follow-up histopathology report was positive for malignancy

“False positive” smear: A Pap smear was labeled as “false positive” if it was reported as GCA, but the follow-up histopathology report was negative for malignancy. The overall percentage of false positives and the histological diagnosis in such cases were documented. The rate of false positives was compared between conventional and LBC smears; only those cases which remained as false positive after review were included for the comparative analysis

“False negative” smears: A Pap smear was labeled as “false negative” if the histopathology report showed malignancy, but the Pap smear was reported as NILM. The overall percentage of false negatives and the histological diagnosis in such cases were documented. The rate of false negative GCA was compared between conventional and LBC smears; only those cases, which remained as false negative after review, were included for the comparative analysis.

RESULTS

The “histopathology search” arm

Out of a total of 21,632 histopathological specimens processed during the study period, a total of 212 EMA and ECA were identified from the histopathology records. Of these, there were 163 endometrioid types of EMA, 16 endometrial papillary serous carcinoma, 5 endometrial clear cell carcinomas, and 28 endocervical (ECA) adenocarcinoma.

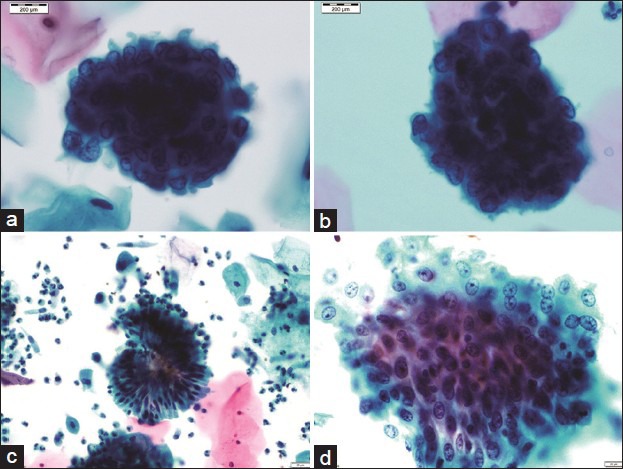

Pap smears predating the histopathological diagnosis were available for 122 cases; of these, 78 were conventional and 44 were LBC samples. On initial reporting, 28/122 (22.9%) smears were reported as having an epithelial cell abnormality. Out of these, 13 were reported as adenocarcinoma, 2 as AGC-FN, 7 as AGC-NOS, 3 as high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion, and 3 as atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS) [Table 1].

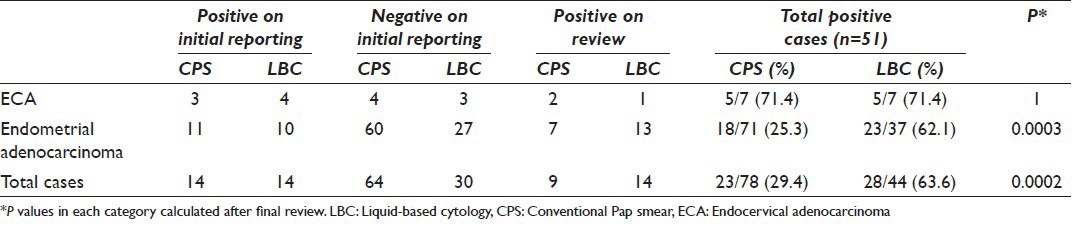

Table 1.

Cytological diagnoses of 122 cases of histopathologically proven uterine adenocarcinomas

A total of 94/122 (77.0%) samples were initially reported as “NILM” [Figure 2]. These 94 cases were reviewed in view of follow-up histopathological diagnosis [Table 2]. After review, 23 of these cases were re-classified as GCA, with 16 cases as adenocarcinoma, 6 as AGC-FN, and 1 as AGC-NOS. Thus, after review, 51/122 Pap smears (41.8%) were reported as having epithelial cell abnormality. Out of these 51 true positive smears, 23/78 (29.5%) were conventional smears and 28/44 (63.6%) were LBC samples, thereby indicating the detection rate of GCA to be 2.2 times higher with LBC samples as compared to conventional smears; this difference was found to be statistically significant (P < 0.05). In the subgroup of ECA, the detection rate for LBC and conventional smears was similar (71.4%). However, in the subgroup of EMA, the detection rate for LBC was significantly higher than conventional smears (LBC = 62.1%; conventional = 25.3%; P = 0.0003) [Table 3].

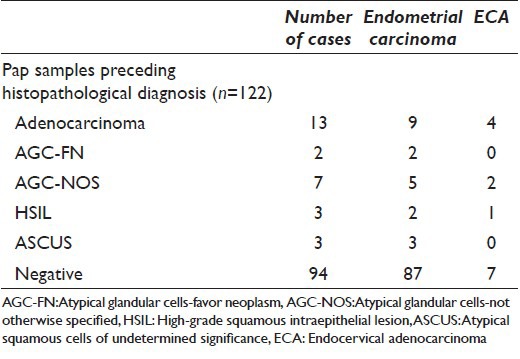

Figure 2.

A panel of microphotographs of SurePath™ liquid-based cytology Pap samples: (a) Benign endometrial cell cluster with top-hat appearance, reported as negative for any intraepithelial lesion or malignancy (Pap, ×100); (b) endometrial cell cluster showing mild nuclear enlargement with occasional cells having conspicuous nucleoli, reported as atypical glandular cell (Pap, ×100); (c) inverted rosette of benign endocervical cells, reported as negative for any intraepithelial lesion or malignancy (Pap, ×40); (d) a flat sheet of endocervical cells showing reactive atypia with prominent nucleoli, reported as atypical glandular cell (Pap, ×40)

Table 2.

Cytological diagnosis after review of false negative Pap smears

Table 3.

Detection rates of endometrial adenocarcinoma and ECA for conventional and LBC smears

The total number of negative smears, even after review, was 71 and therefore the overall sensitivity of Pap smears for detection of GCA was found to be 41.8%.

Cytopathology search arm

A total of 46,394 Pap smear records were identified during the study period, 33,154 were conventional smears (71.5%), and 13,240 (28.5%) were SurePath™ LBC samples. Out of these, 149 (0.3%) smears were reported as GCA, as per TBS 2001.

Out of 149 GCA smears, 96 (64.4%) were reported as AGC-NOS, 14 (9.4%) as AGC-FN, and 39 (26.2%) as adenocarcinoma. Follow-up histopathology samples were available in 103 patients (141 biopsies/resection specimens). Out of these 103 cases, 35 were conventional smears and 68 were LBC samples.

A total of 57/103 (55.3%) patients were positive for malignancy on histopathology [true positives, Table 4]. There were 10 cases of ECA [Figure 3] and 27 cases of EMA [Figure 4], 6 cases of endometrial papillary serous carcinoma, 3 cases of ovarian papillary serous carcinoma, 2 cases of complex atypical hyperplasia, and 1 case of metastatic carcinoma. Four smears (3 reported as adenocarcinoma and 1 as AGC-FN) were reported as SCC (n = 3) and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia-3 (n = 1) on follow-up histopathology. Four smears (2 reported on cytology as AGC-FN and 2 as adenocarcinoma) turned out to be carcinosarcoma on histopathology. Even after review, in view of follow-up histopathology, the sarcomatous component could not be identified in these cases.

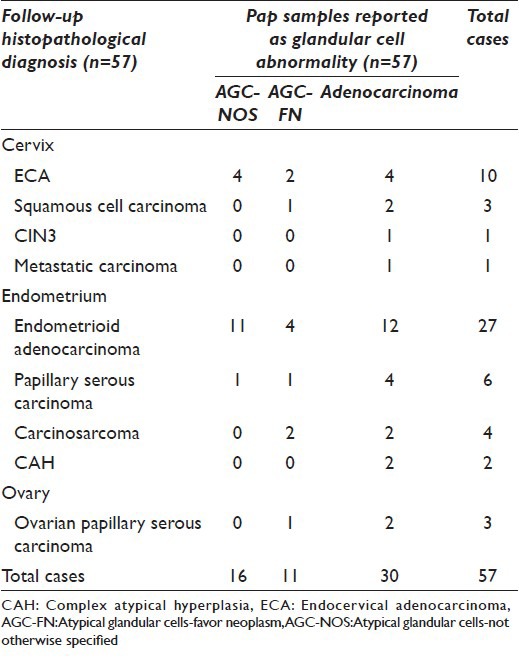

Table 4.

Histopathological correlation of true positive Pap smears

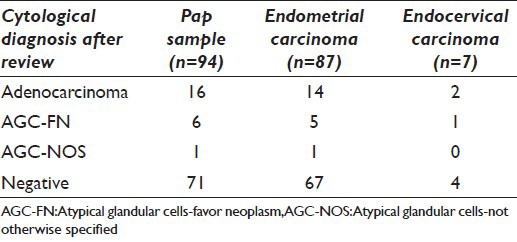

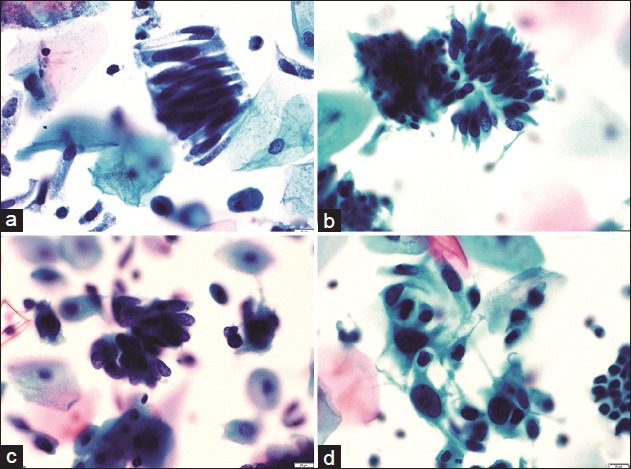

Figure 3.

A panel of microphotographs of SurePath™ liquid-based cytology Pap samples reported as endocervical adenocarcinoma: (a) A pseudo-stratified strip of endocervical cells showing cigar-shaped nuclei (Pap, ×40); (b and c) clusters of endocervical cells showing feathering, nuclear crowding, and snake and egg appearance (Pap, ×40); (d) dispersed population of atypical endocervical cells showing nuclear pleomorphism (Pap, ×40)

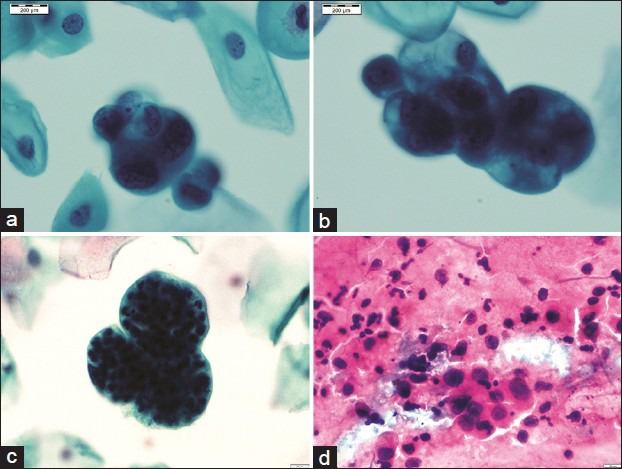

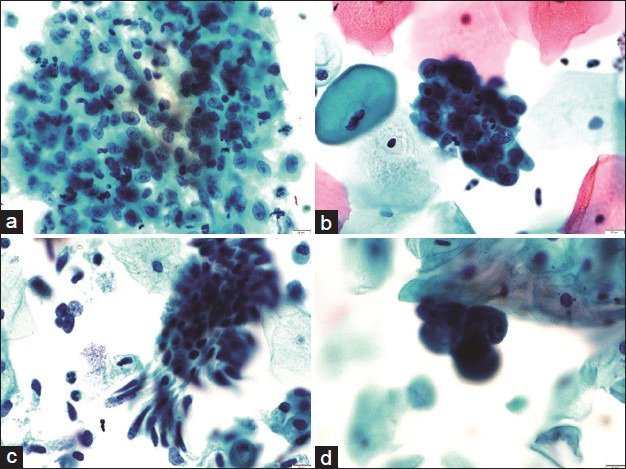

Figure 4.

A panel of microphotographs of Pap samples reported as endometrial adenocarcinoma: (a and b) Three-dimensional clusters of atypical endometrial cells showing nucleomegaly, irregular nuclear membranes, and prominent nucleoli (Pap, ×100); (c) bag of polymorphs (Pap, ×100); (d) conventional smears showing loosely cohesive cluster of atypical glandular cells with dispersed population of similar cells (Pap, ×40)

A total of 46/103 (44.7%) patients, reported originally on cytology as having glandular cell abnormality, were negative for malignancy on follow-up histopathology [false positives, Table 5]. For these 46 cases, there were 42 biopsies/curettage and 4 hysterectomy specimens. Of these, 11 were reported as adenocarcinoma, 9 as AGC-FN, and 26 as AGC-NOS, on cytology [Figure 2]. All these cases with a false positive diagnosis on cytology were reviewed. After review, a revised cytological diagnosis of NILM was given in 28 cases (1 case of adenocarcinoma, 6 of AGC-FN, and 21 of AGC-NOS). Thus, the total false positive cases after review were 18 (17.5%). Of the remaining 18 cases, the initial diagnosis of adenocarcinoma (10 cases) was changed to AGC-FN in 8 cases and AGC-NOS in 2 cases; the initial diagnosis of AGC-FN (3 cases) was changed to AGC-NOS in 2 cases and was unchanged in 1 case; all cases of AGC-NOS remained unchanged. Although the number of false positive cases was more with LBC samples (n = 13), as compared to conventional smears (n = 5), this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.5).

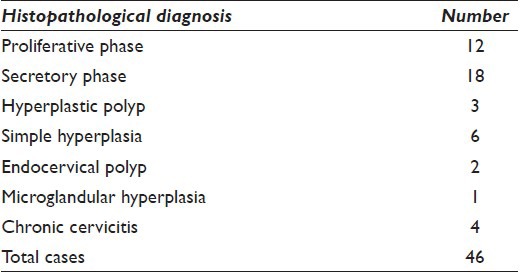

Table 5.

Histopathological diagnosis in false positive Pap smears

The overall specificity of Pap smears for GCA after final review was 60.9%. The specificity was more for LBC samples (63.9%) as compared to conventional smears (50%); however, this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.4).

DISCUSSION

Although Pap smear is a very efficient screening tool for the cervical cancer, the detection rates for glandular lesions are lower, more so for endometrial lesions as compared to endocervical lesions.[13,14]

Lower detection rates of glandular abnormalities in cervical smears may be due to the fact that cervical sampling was designed to evaluate the transformation zone and squamous precancerous lesions. The collection devices used may not be well suited to sample endocervical, lower uterine, and endometrial lesions. Often, only a few cells or occasional clusters of atypical cells are seen on Pap smears in endometrial and other extra-cervical lesions without accompanying tumor diathesis, mainly due to low numbers of exfoliated atypical cells and associated degenerative changes. Moreover, in contrast to squamous lesions, the cellular changes associated with adenocarcinoma of endocervical or endometrial type and their precursor lesions are much more diverse. This contributes to the poor inter-observer reproducibility of their diagnoses.[15,16,17,18,19] To add to the diagnostic difficulty, reactive cellular changes due to innumerable causes can mimic glandular abnormality in cervical smears.[3,4,20] Although rare, glandular lesions can sometimes co-exist with squamous lesions and may be masked by, the more prominent, squamous abnormality.

GCAs recognizable on Pap smears can be of endocervical, endometrial, or extra-uterine origin. These include a variety of lesions including AGC-NOS, AGC-FN, endocervical adenocarcinoma in situ, and endocervical, endometrial, and extra-uterine adenocarcinoma. The diagnostic category of AGC was introduced in the 1988 Bethesda system.[21] Even after more than two decades of its inception, it still remains a diagnostic challenge for the cytopathologists.

Columnar cells of both endocervical and endometrial origin can exhibit significant cytological changes even in the absence of malignancy. Other benign mimics include - follicular cervicitis, microglandular hyperplasia, endometriosis, benign endometrial and endocervical polyps, tubal metaplasia, vaginal tubal prolapse, endometrial hyperplasia, and intrauterine device-related reactive changes.[3,4,7,8,20] This emphasizes the need for the cytopathologists to be cognizant of possible glandular lesions in Pap smears and their diagnostic pitfalls. Among the glandular lesions, sensitivity as well as positive predictive value of cervical cytology, after comparison with follow-up histology is better for endocervical lesions as compared to endometrial lesions and extrauterine malignancies.[22,23] This could be attributable to less frequent exfoliation of malignant cells from the endometrium, sampling being done from the cervix and not the endometrium, exfoliated cells being degenerated, and obscured by inflammation and blood in conventional Pap smears.[24,25]

In our study, the overall incidence of GCA was found to be 0.32%. This is similar to other studies in the literature, which report GCA to be an infrequent diagnosis with the incidence generally being <1%.[6,20,26]

Geldenhuys and Murray evaluated the sensitivity and specificity of the Pap smears for glandular lesions of the cervix and endometrium and found that 80% of Pap smears with ECA and 22% with EMA had positive findings within an year of the histologic diagnosis, with 51% overall positivity.[27] In our study, we observed an overall positivity (after review) of 41.8%.

In our study, 4 cases having squamous cell abnormality were misclassified as having GCA on cytology and there were 6 cases that were reported as squamous epithelial cell lesions (3 HSIL, 3 ASCUS) on cytology, but turned out to be ECA on histopathology. This was mainly due to difficulty in differentiating between atypical squamous and glandular cells on cytology. Some authors, in previous studies, have observed similar difficulty in Pap smears.[5,7,28,29,30]

We had 18 (17.5%) false positive cases, even after review of the smears using stringent diagnostic criteria, as per TBS 2001. This highlights the limitation of the cervical cytology for the precise diagnosis of GCA. Similar results have been observed by previous studies in the literature.[30,31] The high rates of false positivity for GCA may be attributable to over-interpretation of the reactive atypia of the glandular cells, both endometrial and endocervical. The rate of false positivity decreased on review. These findings highlight the importance of careful analysis of all smears and the need for review by a second cytopathologist for smears reported as positive for GCA. Furthermore, we would recommend that all smears reported as positive for GCA should be followed-up with biopsy/curettage for confirmation of the diagnosis.

Majority of the cases reported as AGC-NOS (endocervical) had glandular endocervical cell clusters showing mild to moderate nuclear enlargement, finely dispersed chromatin, conspicuous nucleoli, and smooth thickened cytoplasmic membranes. These were showing reactive/repair changes, which are at times difficult to differentiate from high-grade lesions including invasive tumor. These cases were reviewed in the light of follow-up histopathology. These included cases reported on histopathology as endocervical polyps, microglandular hyperplasia, and papillary endocervicitis. The cases reported as AGC and NOS for endometrial clusters showed endometrial clusters with mild to moderate nuclear enlargement, prominent cytoplasmic vacuolation, smudgy degenerate chromatin, and occasional prominent nucleoli. These cases were reported as simple hyperplasia without atypia or endometrial polyps or proliferative/secretory endometrium on follow-up histopathology [Figure 5].

Figure 5.

A panel of microphotographs of SurePath™ liquid-based cytology Pap samples: (a) A sheet of reactive endocervical cells showing nuclear enlargement and prominent nucleoli, reported initially as atypical glandular cell-not otherwise specified; later revised to negative for any intraepithelial lesion or malignancy (Pap, ×40); (HPE: Chronic cervicitis); (b) a cluster of reactive endometrial cells showing nuclear enlargement, smudgy chromatin, and small nucleoli, reported initially as atypical glandular cell-not otherwise specified; later revised to negative for any intraepithelial lesion or malignancy (Pap, ×40), (HPE: Simple hyperplasia without atypia); (c) cluster of endocervical cells showing moderate nuclear enlargement and crowding, reported as atypical glandular cell-favor neoplasm and not changed on review (Pap, ×40), (HPE: Microglandular hyperplasia); (d) cluster of endometrial cells showing nuclear enlargement and prominent nucleoli, reported as atypical glandular cell-favor neoplasm and not changed on review (Pap, ×40), (HPE: Hyperplastic polyp)

The number of false positive cases in our study was more with LBC samples (n = 13), as compared to conventional smears (n = 5). However, this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.5). We hypothesize that this is because even if a few clusters of glandular cells depicting reactive changes are present in the sample, they are well visualized on LBC samples and are therefore often over-cautiously reported as GCA. On the contrary, even if a few scattered reactive clusters are present in the conventional smears, they are mostly overshadowed by multiple layers of more numerous squamous epithelial cells or may be obscured by the blood, mucous, and inflammatory cells.

There were 71 (58.2%) false negative cases, after review, in our study. Most of these smears did not demonstrate even occasional tumor cells, after extensive review. This might be due to the, already known, infrequent exfoliation of AGC into the cervical canal. Furthermore, we believe that low clinical suspicion and lesser number of tumor cells present in some Pap smears may be the major factors contributing to the false negative diagnoses. This emphasizes the need for slow and systematic screening of Pap smears, observing stringent criteria, with significant overlap of screened areas, so as to minimize detection errors.

An important observation of our study is that the detection rates of glandular lesions improved significantly (2.2 times higher detection in LBC samples; P = 0.0002) with the use of LBC technique. This is in keeping with previous studies.[24,25,32,33] Moreover, it was seen that the detection rate of EMA on LBC samples (62.1%) was significantly higher (2.45 times; P = 0.0003) than conventional smears (25.3%). This is mainly because of cell concentration and better preservation of cellular morphology in LBC samples, in contrast to the conventional smears.

CONCLUSIONS

The results of our study confirm that the prevalence of GCA in Pap smears is low. Pap smears, both conventional and LBC, have moderate specificity for diagnosis of uterine glandular abnormalities. However, the overall sensitivity of Pap smears for the detection of GCA is low, although we found it to be significantly better for LBC as compared to conventional smears. Therefore, we recommend that a high index of suspicion be maintained when screening Pap smears in patients with a history suspicious of uterine glandular lesion. Future research needs to focus on improved methods of screening for uterine glandular abnormalities, in view of the low sensitivity of Pap smears.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

The authors declare that we have no competing interests.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

To give appropriate credit to each author of a paper, the individual contributions of all authors to the manuscript have been specified.

According to International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE http://www.icmje.org), “author” is generally considered to be someone who has made substantive intellectual contributions to a published study.

Authorship credit is based on (1) substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; (2) drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and (3) final approval of the version to be published. Authors meet conditions 1, 2, and 3.

We declare that each author has participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content.

All authors of this article declare that we qualify for authorship as defined by ICMJE. Each author has participated sufficiently in the work and took public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content of this article.

BB, NG, and PG were instrumental in collection and interpretation of data. WE reviewed all smears and follow-up histopathological slides to come to the conclusion. Clinical data and final interpretation was done by VS. Initial acquisition of data, PubMed search, and modification in the manuscript was done by NG and AR.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Each author acknowledges that this final version was read and approved.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

This study was conducted with approval from Institutional Review Board of the institution associated with this study as applicable. This study was a retrospective study not directly involving the patients. Authors take responsibility to maintain relevant documentation in this respect.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS (In alphabetic order)

ASCUS - Atypical squamous cells of undetermined Significance

ECA - Endocervical Adenocarcinoma

EMA - Endometrial Adenocarcinoma

GCA - Glandular Cell Abnormalities

LBC - Liquid-Based Cytology

NILM - Negative for any Intraepithelial Lesion or Malignancy

Pap - Papanicolaou

SCC - Squamous Cell Carcinoma

TBS - The Bethesda System

EDITORIAL/PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double-blind model. (authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system.

Contributor Information

Baneet Bansal, Email: bansalbaneet@aol.in.

Parikshaa Gupta, Email: parikshaa@gmail.com.

Nalini Gupta, Email: nalini203@gmail.com.

Arvind Rajwanshi, Email: rajwanshiarvind@hotmail.com.

Vanita Suri, Email: surivanita@yahoo.co.in.

REFERENCES

- 1.Coste J, Cochand-Priollet B, de Cremoux P, Le Galès C, Cartier I, Molinié V, et al. Cross sectional study of conventional cervical smear, monolayer cytology, and human papillomavirus DNA testing for cervical cancer screening. BMJ. 2003;326:733. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7392.733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim HS, Underwood D. Adenocarcinomas in the cervicovaginal Papanicolaou smear: Analysis of a 12-year experience. Diagn Cytopathol. 1991;7:119–24. doi: 10.1002/dc.2840070203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson JE, Rahemtulla A. Endocervical glandular neoplasia and its mimics in ThinPrep Pap tests. A descriptive study. Acta Cytol. 1999;43:369–75. doi: 10.1159/000331083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chhieng DC, Elgert PA, Cangiarella JF, Cohen JM. Clinical significance of atypical glandular cells of undetermined significance. A follow-up study from an academic medical center. Acta Cytol. 2000;44:557–66. doi: 10.1159/000328530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cangiarella JF, Chhieng DC. Atypical glandular cells – An update. Diagn Cytopathol. 2003;29:271–9. doi: 10.1002/dc.10316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ajit D, Gavas S, Joseph S, Rekhi B, Deodhar K, Kane S. Identification of atypical glandular cells in Pap smears: Is it a hit and miss scenario? Acta Cytol. 2013;57:45–53. doi: 10.1159/000342744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castle PE, Fetterman B, Poitras N, Lorey T, Shaber R, Kinney W. Relationship of atypical glandular cell cytology, age, and human papillomavirus detection to cervical and endometrial cancer risks. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(2 Pt 1):243–8. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181c799a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao C, Austin RM, Pan J, Barr N, Martin SE, Raza A, et al. Clinical significance of atypical glandular cells in conventional Pap smears in a large, high-risk U.S. west coast minority population. Acta Cytol. 2009;53:153–9. doi: 10.1159/000325117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirwan JM, Herrington CS, Smith PA, Turnbull LS, Herod JJ. A retrospective clinical audit of cervical smears reported as ‘glandular neoplasia’. Cytopathology. 2004;15:188–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2303.2004.00163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burnley C, Dudding N, Parker M, Parsons P, Whitaker CJ, Young W. Glandular neoplasia and borderline endocervical reporting rates before and after conversion to the SurePath (TM) liquid-based cytology (LBC) system. Diagn Cytopathol. 2011;39:869–74. doi: 10.1002/dc.21471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ashfaq R, Gibbons D, Vela C, Saboorian MH, Iliya F. ThinPrep Pap Test™. Accuracy for glandular disease. Acta Cytol. 1999;43:81–5. doi: 10.1159/000330872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Papillo JL, Warren SB, Zarka MA. Increased specificity in the detection of glandular lesions: Decreased false positive AGUS with Thin-Prep Pap Test™. Acta Cytol. 1999;43:902. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raab SS. Can glandular lesions be diagnosed in Pap smear cytology? Diagn Cytopathol. 2000;23:127–33. doi: 10.1002/1097-0339(200008)23:2<127::aid-dc13>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gu M, Shi W, Barakat RR, Thaler HT, Saigo PE. Pap smears in women with endometrial carcinoma. Acta Cytol. 2001;45:555–60. doi: 10.1159/000327864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee KR, Darragh TM, Joste NE, Krane JF, Sherman ME, Hurley LB, et al. Atypical glandular cells of undetermined significance (AGUS): Interobserver reproducibility in cervical smears and corresponding thin-layer preparations. Am J Clin Pathol. 2002;117:96–102. doi: 10.1309/HL0B-C7Y6-AC77-ND2U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang N, Emancipator SN, Rose P, Rodriguez M, Abdul-Karim FW. Histologic follow-up of atypical endocervical cells. Liquid-based, thin-layer preparation vs. conventional. Pap smear Acta Cytol. 2002;46:453–7. doi: 10.1159/000326860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simsir A, Hwang S, Cangiarella J, Elgert P, Levine P, Sheffield MV, et al. Glandular cell atypia on Papanicolaou smears: Interobserver variability in the diagnosis and prediction of cell of origin. Cancer. 2003;99:323–30. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koonings PP, Price JH. Evaluation of atypical glandular cells of undetermined significance: Is age important? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:1457–9. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.114849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaferle JE, Malouin JM. Evaluation and management of the AGUS Papanicolaou smear. Am Fam Physician. 2001;63:2239–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wood MD, Horst JA, Bibbo M. Weeding atypical glandular cell look-alikes from the true atypical lesions in liquid-based Pap tests: A review. Diagn Cytopathol. 2007;35:12–7. doi: 10.1002/dc.20589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.The 1988 Bethesda system for reporting cervical/vaginal cytological diagnoses. National Cancer Institute Workshop. JAMA. 1989;262:931–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vuopala S. Diagnostic accuracy and clinical applicability of cytological and histological methods for investigating endometrial carcinoma. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand Suppl. 1977;70:1–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mitchell H, Giles G, Medley G. Accuracy and survival benefit of cytological prediction of endometrial carcinoma on routine cervical smears. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1993;12:34–40. doi: 10.1097/00004347-199301000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patel C, Ullal A, Roberts M, Brady J, Birch P, Bulmer JN, et al. Endometrial carcinoma detected with SurePath liquid-based cervical cytology: Comparison with conventional cytology. Cytopathology. 2009;20:380–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2303.2008.00621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schorge JO, Hossein Saboorian M, Hynan L, Ashfaq R. ThinPrep detection of cervical and endometrial adenocarcinoma: A retrospective cohort study. Cancer. 2002;96:338–43. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Solomon D, Frable WJ, Vooijs GP, Wilbur DC, Amma NS, Collins RJ, et al. ASCUS and AGUS criteria. International Academy of Cytology Task Force summary. Diagnostic cytology towards the 21st century: An International Expert Conference and Tutorial. Acta Cytol. 1998;42:16–24. doi: 10.1159/000331531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geldenhuys L, Murray ML. Sensitivity and specificity of the Pap smear for glandular lesions of the cervix and endometrium. Acta Cytol. 2007;51:47–50. doi: 10.1159/000325682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thamboo TP, Salto-Tellez M, Tan KB, Nilsson B, Rajwanshi A. Cervical cytology: An audit in a Singapore teaching hospital. Singapore Med J. 2003;44:256–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Renshaw AA. Comparing methods to measure error in gynecologic cytology and surgical pathology. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130:626–9. doi: 10.5858/2006-130-626-CMTMEI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moreira MA, Longatto Filho A, Castelo A, de Barros MR, Silva AP, Thomann P, et al. How accurate is cytological diagnosis of cervical glandular lesions? Diagn Cytopathol. 2008;36:270–4. doi: 10.1002/dc.20799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nanda K, McCrory DC, Myers ER, Bastian LA, Hasselblad V, Hickey JD, et al. Accuracy of the Papanicolaou test in screening for and follow-up of cervical cytologic abnormalities: A systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:810–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-10-200005160-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Belsley NA, Tambouret RH, Misdraji J, Muzikansky A, Russell DK, Wilbur DC. Cytologic features of endocervical glandular lesions: Comparison of SurePath, ThinPrep, and conventional smear specimen preparations. Diagn Cytopathol. 2008;36:232–7. doi: 10.1002/dc.20782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Struthers CA, Dziura B. Comparison of ThinPrep Pap with the conventional Pap in the detection of glandular abnormalities. Acta Cytol (Abstr) 1999;43:902. [Google Scholar]