Abstract

Background:

Vitamin C levels are low in pregnancy. The purpose of this study was to determine serum Vitamins C levels among pregnant women attending antenatal care at a General Hospital in Dawakin Kudu, Kano, and this can help further research to determine the place of Vitamin C supplementation in pregnancy.

Methods:

This was a prospective study of 400 pregnant women who presented for antenatal care in General Hospital Dawakin Kudu, Kano, Nigeria. Research structured questionnaire was administered to 400 respondents. Determination of serum Vitamin C was done using appropriate biochemical methods.

Results:

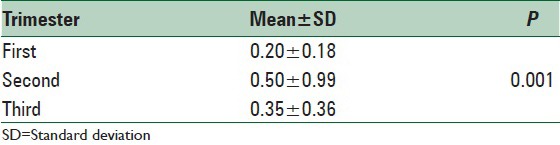

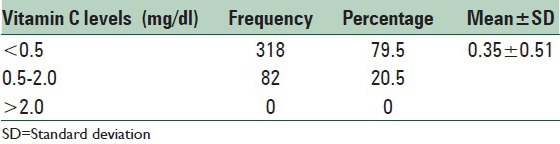

Vitamin C deficiency was found in 79.5% of the participants. The values for Vitamin C were 0.20 ± 0.18 mg/dl during the first trimester, 0.50 ± 0.99 mg/dl in the second trimester, and 0.35 ± 0.36 mg/dl in the third trimester and P = 0.001.

Conclusions:

There is a significant reduction in the serum Vitamins C concentration throughout the period of pregnancy with the highest levels in the second trimester. Therefore, Vitamin C supplementation is suggested during pregnancy, especially for those whose fruit and vegetable consumption is inadequate.

Keywords: North-west Nigeria, pregnant women, Vitamin C

INTRODUCTION

Vitamin C, also known as ascorbic acid, like other vitamins is an organic substance, which is required by the body in small amounts to maintain life and health.[1] It acts as a catalyst in the formation of hormones, enzymes, blood cells, neurotransmitters, and genetic materials.[1] It is also essential to complete the metabolism of carbohydrates, proteins, and fats. The body's need for Vitamin C is met by diet, especially fruits. Vitamin C has antioxidant properties and as such either blocks the initiation of free radical formation or inactivate (scavenge) free radical.[2]

Vitamin C levels in the third trimester has been shown to be lower than the levels in the first and second trimester due to physiological changes in pregnancy leading to hemodilution[3] and deficiency of Vitamin C may be associated with some complications in pregnancy.[4]

Vitamin C supplementation has been shown in some studies to reduce the risk of premature rupture of placental membranes and premature births, gestational hypertension, intrauterine growth retardation, and gestational diabetes in addition to other health benefits.[5,6,7,8,9] Furthermore, because Vitamin C enhances iron absorption,[10,11] the low serum ascorbate can lead to a decrease in the absorption and subsequent utilization of iron which is required for the proper maintenance of pregnancy and fetal growth.

Data from Nigeria on Vitamin C status among pregnant women are few. The purpose of this study was to determine serum Vitamins C levels among pregnant women attending antenatal care at a General Hospital in Dawakin Kudu, Kano, Nigeria, and this can help further research to determine the place of Vitamin C supplementation in pregnancy.

METHODS

This was a prospective study of 400 pregnant women at various maternal ages, gestational ages and parities done between 31 November 2009 and 30 March 2011. Ethical approval for the research was obtained from General Hospital, Dawakin Kudu, Kano, Nigeria. Informed consent was obtained from the participants.

Dawakin Kudu is a rural community in Kano State, Nigeria, and about 10 km from Kano, the commercial nerve center of Northern Nigeria. Most of the women are homemakers.

Research structured questionnaire was administered to 400 respondents randomly selected and this showed various sociodemographic indices.

Documented prevalence of 32.26% (20 out of 62) from previous study was used.[12] This study was chosen because it was done in a similar setting in Nigeria. The sample size was rounded up to 450 pregnant women to account for dropout. Participants with confounders such as hypertensive diseases and diabetes mellitus were excluded.

Whole blood sample (5 ml) was collected from the 400 participants and drawn directly into a plain blood sample container. Centrifugation at 2500–3000 rpm for 5 min was done to obtain plasma. They were labeled and covered with aluminum foils. Storage was in a deep freezer for 1 month. Determination of serum Vitamin C level, according to Roe and Kuether, 1943,[13] and normal range was 0.5–2 mg/dl.

Data obtained were analyzed using SPSS version 17 statistical software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive statistics was used for quantitative variables. Mean serum Vitamins C concentrations between trimesters were compared using one-way ANOVA and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

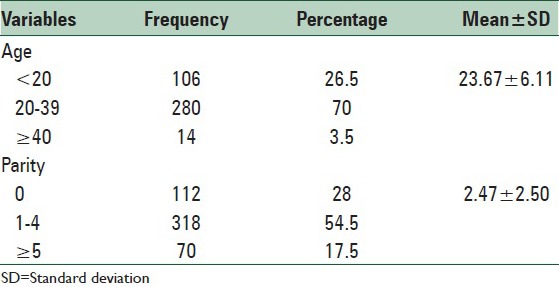

Results are shown in Tables 1–3. Out of 450 participants, 400 completed the study. Participants who could not be followed-up or who developed confounders such as hypertensive diseases or diabetes mellitus were dropped. Majority of the women were aged 20–39 years with a mean of 23.67 ± 6.11. Most were in the 1–4 parity range. Seventy-nine and half percentage (79.5%) of the women had Vitamin C deficiency. The values for Vitamin C were 0.20 ± 0.18 mg/dl during the first trimester, 0.50 ± 0.99 in the second trimester, and 0.35 ± 0.36 mg/dl in the third trimester. The differences between the vitamins from one trimester to the other were statistically significant (P < 0.05).

Table 1.

Age and parity distribution

Table 3.

Pattern of serum Vitamins C levels in mg/dl across trimesters

Table 2.

Serum Vitamins C levels of the study sample

DISCUSSION

The present study reports that majority of the women were aged 20–39 years and a mean of 23.67 ± 6.11 was reported. The previous study reported mean age of 27.2 ± 6.5 years.[14] The association between the status of Vitamin C and maternal age has been studied, and the highest levels were found among the age group 22–25 years and the lowest levels in the age group 34–37 years.[6]

Majority of the women in this study were in the 1–4 parity range. Some local studies have reported that the serum Vitamin C levels decrease with parity because multiparous women in our environment may have depleted vitamin storage from frequent pregnancies at short intervals.[15]

The present study reports low serum Vitamin C levels among this cohort of pregnant women and this was significant across the three trimesters. This study reports a prevalence of Vitamin C deficiency of 79.5%. A previous study from the northwestern part of Nigeria reported a lower prevalence of 32.3%.[12] This difference may be related to the high parity, inadequate nutrition, and nutritional taboos among Northern Nigeria pregnant women. A similar prevalence of 75% was earlier reported from a rural setting in India.[16] Similar studies found significant reduction in serum Vitamin C in pregnant Nigerians.[17,18] Contrary to other studies, plasma Vitamin C decline during pregnancy did not follow a linear trend with time.[17,18] Vitamin C deficiency may be accounted partly by the physiological hemodilution of pregnancy, inadequate intake, and the use of Vitamin C to combat the oxidative stress of pregnancy.[19]

This study has shown deficient Vitamin C status among pregnant women attending antenatal clinic at General Hospital Dawakin Kudu, Kano, and there is a significant reduction across trimesters. Although data on Vitamin C supplementation in pregnancy are conflicting,[20,21,22] Vitamin C supplementation can be suggested during pregnancy, especially for those whose fruit and vegetable consumption is inadequate because of aforementioned benefits. Vitamin C supplementation could also help to prevent the development of such complications of pregnancy such as gestational hypertension, intrauterine growth retardation, and gestational diabetes, conditions all known to be associated with high levels of oxidative stress.[23] Studies from less-developed economies where Vitamin C deficiency among pregnant mothers is prevalent showed significant benefit of Vitamin C supplementation during pregnancy in reducing low birth weight and small for gestational age births.[7,24] Vitamin C may be protective against development of preeclampsia.[25,26] It has also been shown that supplementation with Vitamins C and E after preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM) is associated with a statistically significant increase in difference in the number of days before delivery.[27] However, another study was of the contrary and does not support Vitamin C use for management or prevention of PPROM.[28]

Decision as to which micronutrients are of greatest concern in developing countries requires a more systematic and comprehensive approach.[29]

CONCLUSIONS

There is a significant reduction in the serum Vitamins C concentration throughout the period of pregnancy with the highest levels in the second trimester Therefore, Vitamin C supplementation is suggested during pregnancy, especially for those whose fruit and vegetable consumption are inadequate.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledges the technical support provided by the laboratory staff of General Hospital Dawakin Kudu, during the preparation of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Klufio CA. Nutrition in pregnancy. In: Kwawukume EY, Emuveyan EE, editors. Comprehensive Obstetrics in the Tropics. Dansoman: Asante and Hittcher Limited; 2002. pp. 21–3. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halliwell B. How to characterize a biological antioxidant radicals. Res Commun. 1990;9:1–30. doi: 10.3109/10715769009148569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoshioka T. Vitamins in pregnancy. Nihon Rinsho. 1999;57:2381–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Therieko PA, Ettes SX. Plasma ascorbic acid levels in Nigerian mothers and newborn. J Trop Pediatr. 1981;27:263–6. doi: 10.1093/tropej/27.5.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casanueva E, Viteri FE. Iron and oxidative stress in pregnancy. J Nutr. 2003;133(5 Suppl 2):1700S–8S. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.5.1700S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frei B, England L, Ames BN. Ascorbate is an outstanding antioxidant in human blood plasma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:6377–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.16.6377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rumbold A, Crowther CA. Vitamin C supplementation in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;18:CD004072. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004072.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casanueva E, Ripoll C, Meza-Camacho C, Coutiño B, Ramírez-Peredo J, Parra A. Possible interplay between Vitamin C deficiency and prolactin in pregnant women with premature rupture of membranes: Facts and hypothesis. Med Hypotheses. 2005;64:241–7. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Osaikhuwuomwan JA, Okpere EE, Okonkwo CA, Ande AB, Idogun ES. Plasma Vitamin C levels and risk of preterm prelabour rupture of membranes. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;284:593–7. doi: 10.1007/s00404-010-1741-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharma DC, Mathur R. Correction of anemia and iron deficiency in vegetarians by administration of ascorbic acid. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 1995;39:403–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whitney EA, Hamilton EM. Understanding Nutrition. 3rd ed. Minnesota: West Publishing Company; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ariyo O, Keshinro OO. serum ascorbic acid levels in the third trimester of pregnancy and ascorbate content of maternal breast milk. Cont J Med Res. 2012;6:30–6. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roe JH, Kuether CA. The determination of ascorbic acid in whole blood and urine through the 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine derivative. J Biol Chem. 1943;147:399–407. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sylvester IE, Paul A. Effects of socio demographic factors on plasma ascorbic acid and alpha tocopherol antioxidants during pregnancy. Pak J Med Sci. 2009;25:755–9. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ejezie EE, Onwusi EA, Nwagha UI. Some biochemical markers of oxidative stress in pregnant Nigerian women. Trop J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;21:122–4. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chiplonkar SA, Agte VV, Mengale SS, Tarwadi KV. Are lifestyle factors good predictors of retinol and Vitamin C deficiency in apparently healthy adults? Eur J Clin Nutr. 2002;56:96–104. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Uchenna IN, Fedilis EE. Serum ascorbic acid level during pregnancy in Enugu, Nigeria. J Col Med. 2005;10:43–5. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ugwa E, Gwarzo M, Ashimi A. Oxidative stress and antioxidant status of pregnant rural women in north-west Nigeria: Prospective cohort study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015;28:544–7. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2014.924102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stark JM. Inadequate reducing systems in pre-eclampsia: A complementary role for Vitamins C and E with thioredoxin-related activities. BJOG. 2001;108:339–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2001.00100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kontic-Vucinic O, Terzic M, Radunovic N. The role of antioxidant vitamins in hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. J Perinat Med. 2008;36:282–90. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2008.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holmes VA, McCance DR. Could antioxidant supplementation prevent pre-eclampsia? Proc Nutr Soc. 2005;64:491–501. doi: 10.1079/pns2005469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chappell LC, Seed PT, Kelly FJ, Briley A, Hunt BJ, Charnock-Jones DS, et al. Vitamin C and E supplementation in women at risk of preeclampsia is associated with changes in indices of oxidative stress and placental function. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187:777–84. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.125735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olayaki LA, Ajao SM, Jimoh GA, Aremu IT, Soladoye AO. Effect of Vitamin C on malondialdehyde (MDA) in pregnant Nigerian women. J Basic Appl Sci. 2008;4:105–8. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bodnar LM, Tang G, Ness RB, Harger G, Roberts JM. Periconceptional multivitamin use reduces the risk of preeclampsia. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164:470–7. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Borna S, Borna H, Daneshbodie B. Vitamins C and E in the latency period in women with preterm premature rupture of membranes. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2005;90:16–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2005.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gungorduk K, Asicioglu O, Gungorduk OC, Yildirim G, Besimoglu B, Ark C. Does Vitamin C and Vitamin E supplementation prolong the latency period before delivery following the preterm premature rupture of membranes? A randomized controlled study. Am J Perinatol. 2014;31:195–202. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1343774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hauth JC, Clifton RG, Roberts JM, Spong CY, Myatt L, Leveno KJ, et al. Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network (MFMU). Vitamin C and E supplementation to prevent spontaneous preterm birth: A randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:653–8. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181ed721d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Swaney P, Thorp J, Allen I. Vitamin C supplementation in pregnancy – Does it decrease rates of preterm birth? A systematic review. Am J Perinatol. 2014;31:91–8. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1338171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ugwa EA. Vitamin C supplementation in pregnancy: A review of current literature. Niger J Basic Clin Sci. 2015;12:1–5. [Google Scholar]