Abstract

Background

Multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (MDRAB) is difficult to treat and eradicate. Several reports describe isolation and environmental cleaning strategies that controlled hospital MDRAB outbreaks. Such interventions were insufficient to interrupt MDRAB transmission in two intensive care unit-based outbreaks in our hospital. We describe strategies that were associated with termination of MDRAB outbreaks at the NIH Clinical Center.

Methods

In response to MDRAB outbreaks in 2007 and 2009, we implemented multiple interventions, including stakeholder meetings, enhanced isolation precautions, active microbial surveillance, cohorting, and extensive environmental cleaning. We conducted a case-control study to analyze risk factors for acquiring MDRAB. In each outbreak, infection control adherence monitors were placed in MDRAB cohort areas to observe and correct staff infection control behavior.

Results

Between May 2007 and December 2009, 63 patients acquired nosocomial MDRAB; 57 (90%) acquired one or more of four outbreak strains. Of 347 environmental cultures, only 2 grew outbreak strains of MDRAB from areas other than MDRAB patient rooms. Adherence monitors recorded 1330 isolation room entries in 2007, of which 8% required interventions. In 2009, around-the-clock monitors recorded 4892 staff observations, including 127 (2.6%) instances of nonadherence with precautions requiring 68 interventions (1.4%). Physicians were responsible for more violations than other staff (58% of hand hygiene violations and 37% of violations relating to gown and glove use). Each outbreak terminated in temporal association with initiation of adherence monitoring.

Conclusions

Although labor-intensive, adherence monitoring may be useful as part of a multifaceted strategy to limit nosocomial transmission of MDRAB.

Keywords: Acinetobacter, adherence monitor, isolation precautions, outbreak

Introduction

Multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (MDRAB) infections are serious and increasingly frequent complications of hospital care, causing nosocomial outbreaks attributed to environmental contamination and person-to-person transmission.1–6 Outbreaks caused by these and other highly-resistant gram-negative bacilli are among the most vexing problems facing medicine and healthcare epidemiology.

The NIH Clinical Center (CC), a 240-bed clinical research hospital providing care for a largely immunosuppressed patient population, experienced two significant outbreaks of MDRAB infection in a two-year period. Both outbreaks were based in the hospital’s 18-bed medical-surgical intensive care unit, where the nurse-to-patient ratio is about 1:1. The first outbreak began in the summer of 2007 and persisted for six months, despite escalating infection control interventions. After 11 months of inactivity, MDRAB transmission recurred in 2008, when two historical strains reemerged at low levels of transmission. In August 2009, a recently imported strain led to a second outbreak.

We describe the successful termination of two MDRAB outbreaks that occurred two years apart. In both instances, outbreak termination was temporally associated with the use of dedicated infection control adherence monitors. We report the successful management of these outbreaks to underscore several points: 1) these organisms can be eradicated from institutions without having them become endemic pathogens; 2) a multidisciplinary team approach is crucial to outbreak management; and 3) strategies that increase adherence to traditional isolation precautions details, such as dedicated adherence monitors, although resource-intense, may be important components of any intervention designed to reduce risks for transmission, especially in high-risk settings.

Methods

Engaging Stakeholders

During each outbreak, we convened a team involving all potential hospital-based stakeholders and met frequently to address the problem. The team included intensivists, surgeons, ICU nurses, microbiologists, respiratory therapists, housekeeping staff, nutrition staff, infectious diseases specialists, hospital administration, and hospital epidemiology staff. The purpose of these meetings was to analyze the epidemic as it was occurring, share data from the outbreak investigation, generate additional ideas about interventions and develop a consensus about a uniform approach to controlling MDRAB spread. The frequency of the meetings naturally declined as each outbreak slowed down.

Infection Control Interventions

Early in each outbreak, a set of infection control interventions was selected by consensus and implemented simultaneously. Interventions implemented in each outbreak and between outbreaks are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

OUTBREAK CONTROL INTERVENTIONS

| 2007 OUTBREAK | BETWEEN OUTBREAKS | 2009 OUTBREAK |

|---|---|---|

| Daily to weekly stakeholder meetings | Intermittent, smaller stakeholder meetings | Weekly stakeholder meetings |

| Broad hand hygiene and isolation education | Hand hygiene and isolation education | Broad hand hygiene and isolation education |

| Monitored hand gel consumption | ||

| Enhanced contact isolation of all MDRAB patients; empiric enhanced contact isolation of all ICU patients | Enhanced contact isolation of all MDRAB patients; empiric enhanced contact isolation of all ICU patients only when MDRAB patient in the ICU | Enhanced contact isolation of all MDRAB patients; empiric enhanced contact isolation of all ICU patients |

| Active surveillance on all ICU patients during and following ICU stay | Active surveillance on all ICU patients only when MDRAB patient in the ICU | Active surveillance on all ICU patients during ICU stay |

| Geographic and nurse cohorting of MDRAB patients | Geographic cohorting of MDRAB patients | Geographic and nurse cohorting of MDRAB patients |

| Extensive environmental cleaning of the ICU | Extensive environmental cleaning of the ICU | Extensive environmental cleaning of the ICU |

| Strongly encouraged antimicrobial stewardship | Encouraged antimicrobial stewardship | |

| Periodic environmental cultures | Periodic environmental cultures | |

| Isolation adherence monitors | Isolation adherence monitors |

Enhanced Contact Isolation

Given the initial failure of contact precautions to arrest transmission of MDRAB, all ICU patients, including those not known to have MDRAB infection or colonization, were placed on enhanced contact isolation. Precautions included universal use of gowns and gloves for all staff and visitors entering patient rooms, restrictions on patient activity outside rooms, restrictions on staff and visitor traffic, use of disposable meal trays, dedicating equipment for single-patient use, fastidious cleaning of shared equipment, and double-cleaning of vacated rooms. Documented MDRAB carriers who were discharged from the hospital were empirically placed on enhanced contact isolation at any readmission or outpatient visit.

Active Surveillance

During both outbreaks, we performed active surveillance cultures on ICU patients not already known to be MDRAB colonized or infected. Throat and groin swabs (BBL CultureSwab with Stuart’s Transport Medium, Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD) were performed on ICU admission and then twice weekly. During the 2007 outbreak, surveillance culture-negative patients transferred to another unit remained in enhanced contact isolation until they had three additional negative paired surveillance cultures over a week. Because of the low yield of these post-ICU-discharge cultures (no new carriers were identified using this technique), that practice was not resumed during the 2009 outbreak.

Environmental Cultures

Environmental surveillance cultures were collected using different methodologies in 2007 and 2009. In 2007, cotton-tipped swabs were moistened with sterile saline and surfaces vigorously scrubbed. In 2009, in an attempt to increase environmental culture yield, 2”x 2” squares of sterile gauze were moistened with Fastidious broth (Hardy Diagnostics, Santa Maria, CA) then, using sterile gloves, applied systematically to high-touch surfaces in patient rooms. The gauze was then re-immersed in broth. Two squares of gauze were used per sample and two samples were taken in each room; one included the bed and environmental items proximal to the bed, the second included environmental items distal from the bed and bathroom.

Additional ICU sampling using the same technique was performed on shared equipment and areas such as portable monitors, electrocardiography machines, hemodialysis machines, handrails, nursing station surfaces, portable computer workstations, and IV pumps.

Microbiologic Methods

Clinical and surveillance swab specimens were inoculated onto blood agar and MacConkey agar, and incubated at 35–37°C for 48 hours in an air incubator supplemented with 5–7% CO2. Environmental specimens collected on moistened gauze pads were incubated overnight in Fastidious broth and then subcultured onto blood agar and MacConkey agar. Suspicious colonies were evaluated using Gram’s Stain and organisms morphologically consistent with Acinetobacter underwent identification and susceptibility testing.

Isolates of MDRAB from clinical, surveillance, and environmental samples were typed and compared using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) following lysozyme lysis, DNA extraction, and subsequent digestion by Apa1 restriction enzyme (Promega, Madison, WI).13

Adherence Monitors

Because transmission continued to occur despite the aforementioned interventions and intermittent monitoring by infection control staff, the hospital assigned four nurses to monitor adherence to recommended infection control precautions for six weeks in late 2007. One nurse at a time was stationed conspicuously directly outside MDRAB cohorted ICU rooms for 12 hours daily on intermittent weekdays. Infection control staff trained each nurse to monitor and correct prospectively behaviors of staff and visitors entering and leaving isolation rooms, including hand hygiene, proper use of gloves and gown, and equipment disinfection. The nurses were asked to document observations and interactions with staff members and visitors.

Similarly, three months following the onset of the 2009 outbreak, the hospital hired five contract nurses as round-the-clock adherence monitors. After training, monitors were stationed conspicuously directly outside the MDRAB cohorted ICU rooms for 10 weeks. Monitors recorded job categories of staff members entering rooms of MDRAB infected and colonized patients, in addition to details of each entry and exit.

Case-Control Study

Following the 2007 outbreak, we performed a matched case-control study to identify risk factors for MDRAB infection and colonization. MDRAB patients were matched 1:2 to controls by date of admission to the same hospital unit in which the corresponding case patient’s first positive culture was obtained. Clinical data, including demographic parameters, immune status, antibiotic exposure, and other treatment variables were extracted from medical records for the 6-week period before the positive culture. Descriptive statistics and frequency distributions were used to characterize subjects. Comparisons between groups were made using analysis of variance or conditional logistic regression analyses, as appropriate. Univariate conditional logistic regression analyses assessed each variable independently, and multivariable analyses using forward selection were performed for identifying key risk factors for MDRAB colonization and infection. Data were analyzed using SAS v 9.1 (Carey, NC), and p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Magnitude and Impact of Outbreaks

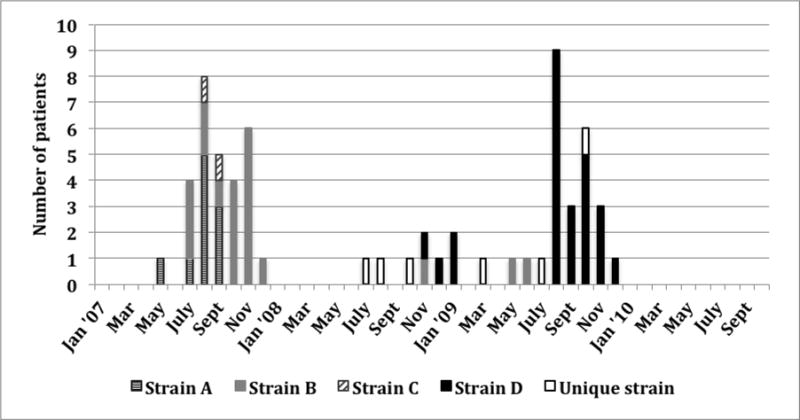

Sixty-three patients were infected or colonized with MDRAB between May 2007 and December 2009 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Epidemic curve of MDRAB acquisition by strain and by month, January 2007 through October 2010.

Patients who acquired more than one strain of MDRAB were classified with the strain they acquired first, or, if both were detected simultaneously, with the strain that predominated on followup cultures.

In the first outbreak, MDRAB was isolated from 29 inpatients between May and December 2007, (18 clinical cultures and 11 surveillance cultures). All but two MDRAB patients had ICU stays overlapping those of other MDRAB patients. (The two non-ICU patients overlapped with MDRAB patients on other wards to which they were transferred.)

Following the 2007 outbreak, no instances of MDRAB colonization or infection with outbreak strains occurred during the ensuing 11 months. From November 2008 to July 2009, two strains of MDRAB were transmitted intermittently, with seven newly affected patients.

In the second outbreak, MDRAB was isolated from 22 patients between August and November 2009,(14 clinical cultures,8 surveillance cultures). All but three had ICU stays overlapping with other MDRAB patients.

In both outbreaks, MDRAB patients were almost uniformly immunosuppressed, and had multiple risk factors for infection. Of 63 patients, 22 (35%) had undergone stem cell transplantation. Among 34 patients (56%) who died following MDRAB acquisition, MDRAB was judged to be the direct cause of death in 11 and to have contributed to death in 11 additional patients.

Since termination of the 2009 outbreak in December 2009, only one new MDRAB isolate (unrelated to all previous isolates by PFGE) has been identified. None of the epidemic strains from either epidemic have been recovered in culture for the past 16 months.

Strain typing

Strain typing showed that 57 patients (90%) were infected or colonized with outbreak strains. In the 2007 outbreak, three strains affected 28 patients: strain A (11; 39%) predominated early in the outbreak, strain B (17; 61%) in the latter three months, and strain C in four cases (14%). Five patients (17%) harbored more than one strain (Figure 1). One patient had a strain with a unique pulsotype.

From November 2008 to July 2009, we observed intermittent transmission of the 2007 outbreak Type B strain to four patients, another five patients with unique MDRAB pulsotypes, as well as introduction of a new strain (strain D). This latter isolate was first identified in November 2008 from a clinical culture from a patient who had received extensive care at another facility. That patient’s strain was subsequently recovered from two other patients who used the same hydrotherapy tub as the index patient. Environmental cultures obtained from the tub yielded the identical MDRAB strain. No other patients used the tub during the outbreak period.

The spate of MDRAB cases in 2009 was a clonal outbreak; 21 of 22 patients had strain D, and a single patient had a unique pulsotype. All strain D patients overlapped with other strain D patients in the ICU.

Environmental Cultures

In the 2007 outbreak, extensive sampling of the ICU environment (148 cultures, including staff cell phones, pagers, badges, and stethoscopes) yielded only three positive cultures. One of these (strain A) was obtained from the bed rail release button in the room of a discharged MRDAB strain A patient that had been cleaned. The other two positive cultures (strain B) were obtained from the room of a known MDRAB strain B patient prior to cleaning. One-time cultures of the identification badges and cell phones belonging to ICU personnel collected during morning rounds yielded no A. baumannii.

In April 2009, a number of inpatients units, including the ICU, were cultured for both VRE and Acinetobacter. Among 145 environmental samples, only four, all obtained from the rooms of current MDRAB patients, grew MDRAB. A few months later during the 2009 outbreak, and despite use of a culturing technique that sampled broader areas, only one of 54 environmental cultures (from a portable cardiorespiratory monitor) from the ICU yielded MDRAB (the epidemic strain D).

Case-Control Study

Among 29 patients affected by nosocomial pulsotypes in the 2007 outbreak, 28 patients were matched to 56 controls. One patient was not included because her isolate was identified as a nosocomial strain only after completion of the study. Cases and controls had no significant differences in age, race, ethnicity, or gender. Cases were significantly more likely to have undergone HSCT (9 of 28 [32%] versus 5 of 56 [9%], p=0.005).

In univariate conditional analysis, MDRAB acquisition was significantly associated with a number of clinical factors related to severe illness (Table 2). In a multivariable conditional model, no single antibiotic emerged as a significant risk factor for MDRAB acquisition. The analysis identified ICU stays of 1 week, blood product transfusion, and neutropenia as the strongest predictors (Table 2).

Table 2.

Case-Control Study of MDRAB Acquisition in 2007 Outbreak

| Clinical variable | Conditional Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| UNIVARIATE ANALYSIS | |||

| ICU stay | 24.12 | 3.15–184.51 | <0.001 |

| No. ICU days | 1.37 | 1.12–1.67 | <0.001 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 29.05 | 3.84–220.00 | <0.001 |

| Blood product transfusion | 13.49 | 3.09–58.82 | <0.001 |

| Renal failure | 4.26 | 1.48–12.25 | 0.004 |

| Neutropenia1 | 7.39 | 2.10–26.00 | 0.001 |

| Wound care | 12.56 | 2.83–55.66 | <0.001 |

| Receipt of antibiotics: | |||

| Ceftazidime | 3.35 | 1.23–9.09 | 0.014 |

| Meropenem | 10.56 | 2.38–46.89 | <0.001 |

| Aminoglycosides | 10.57 | 1.26–89.01 | 0.008 |

| Fluoroquinolones | 6.90 | 2.29–20.77 | <0.001 |

|

| |||

|

MULTIVARIABLE ANALYSIS2

| |||

| ICU stay ≥ 7 days | 45.93 | – | <0.001 |

| Blood product transfusion | 12.08 | – | 0.006 |

| Neutropenia1 | 11.01 | – | 0.048 |

Neutropenia is defined as absolute neutrophil count < 500

95% CI could not be computed due to invalid standard errors in the multiple conditional logistic regression model using forward selection

Infection Control Adherence Monitors

In the 2007 outbreak, adherence monitors documented 107 corrective interventions (8.0%) among 1330 observed entries into ICU MDRAB isolation rooms over 18 days in November-December 2007 (an average of 74 monitored room entries/day). The last MDRAB isolate was identified three weeks following the assignment of adherence monitors, and no new cases were identified in the ensuing 11 months.

In the 2009 outbreak, monitors recorded 5345 observations (an average of 76 per day), of which 4892 (91.5%) involved hospital staff entering rooms. The majority of observations (88.6%) were collected in the ICU, where nearly all MDRAB patients were located and where most nosocomial transmission occurred. At times when no MDRAB patients were in the ICU, monitors were stationed on other units to which MDRAB patients were transferred.

The 2009 monitor observations documented that the majority of staff independently complied with precautions (4781 staff observations; 95.7%). Some (68; 1.4%) responded to reminders and subsequently adhered to recommended guidelines. In 127 instances staff failed to correct behaviors and remained non-adherent despite monitor intervention, accounting for 2.6% of all staff observations. Physicians were responsible for more infection control violations than other staff categories. Five instances of noncompliance were associated with medical emergencies and 52 were associated with conduct of formal rounds by medical or surgical teams. After the initiation of round-the-clock adherence monitoring, we identified no new cases of MDRAB transmission.

Discussion

Most nosocomial Acinetobacter outbreaks occur in intensive care units,5 where patients are especially vulnerable to MDRAB due to the severity of underlying illnesses and the presence of invasive devices that provide convenient portals of entry. Despite more than 150 reports of healthcare-associated MDRAB outbreaks in the literature, we still have an incomplete understanding about the relative importance of factors contributing to its spread. The role of healthcare providers, fomites, and the inanimate environment in the spread of MDRAB remains indistinct, and likely varies from setting to setting and from outbreak to outbreak.

Based on adherence monitors’ observations and the paucity of positive cultures from our inanimate environment in both outbreaks, we conclude that nosocomial spread of MDRAB in our hospital was most likely due to transmission from healthcare worker-to-patient resulting from insufficient attention to infection prevention precautions, such as hand hygiene, proper use of personal protective equipment, and disinfection of patient equipment.15 The demographics of affected patients and the outcome of the case-control study demonstrate the severity of illness and the high degree of immune compromise among patients who acquired MDRAB outbreak strains. For such highly vulnerable patients, 37% of whom had undergone stem cell transplantation, even infrequent breaches of infection control protocol may result in spread of this hardy organism.

In our view, a crucial aspect of controlling the spread of MDRAB was engaging all potential stakeholders as a team to address the problem. These collaborative team meetings were well attended by staff at every level and from numerous departments. As a result, we were able to maintain alignment of the group throughout the investigation and interventions.16

The 2007 case-control study highlighted length of ICU stay, neutropenia, and blood product transfusion as significant risk factors in multivariable analysis. Transfusion was most likely a marker of severity of illness linked with other risk factors rather than a potential source of infection; patients who had neutropenia and prolonged ICU stays were also receiving blood product support. The results of the case-control study supported the observation that severely ill patients with long ICU stays were most vulnerable to MDRAB infection and colonization.

Other hospitals’ experiences have suggested environmental contamination as a frequent source of nosocomial MDRAB transmission.5,17–19 We did document transmission of the D strain from one patient to two others via a hydrotherapy tub, but found only a single contaminated surface in the ICU during each outbreak. The paucity of positive environmental cultures suggests that contamination of health care workers’ hands and/or inadequate adherence to other infection control precautions provided the vehicle for the spread of MDRAB in our institution. This hypothesis is supported by the adherence monitor data from 2009.

Our experiences with two large clonal outbreaks suggest that use of short-term infection control adherence monitors was temporally associated with eradicating MDRAB transmission. One possible explanation for this association is the Hawthorne effect, (i.e., that staff’s awareness of the ongoing monitoring resulted in improved adherence to recommended precautions). Whereas Manian and Ponzillo found that only 76% of 1504 surreptitiously observed staff members were compliant with barrier precautions,28 data from our adherence monitors show that the overwhelming majority of health care personnel, conspicuously observed, adhered fully to the implemented infection prevention measures. Our monitors were proactive in correcting infection control behavior; their presence and interventions surely altered staff behavior. A second possibility for the association is the documented seasonality of nosocomial MDRAB outbreaks.24–27

Our monitors successfully corrected behavior in several dozen cases. In nearly twice as many instances, staff (primarily physicians) remained non-compliant despite the monitors’ interventions. Such non-compliance could permit continued MDRAB spread. Poor adherence to infection control measures also was associated with large medical teams making interdisciplinary rounds. We surmise that herd behavior involved with this activity likely sanctioned the abandonment of infection control measures and overrode the better judgment of health care workers. This mentality may potentially put patients at risk.

Limitations of this report include the simultaneous implementation of a menu of infection control interventions, the fact that we used a few different methods in each outbreak, and the absence of historical or contemporaneous controls to show the effectiveness of our interventions, including adherence monitoring. We do not know what proportion of the staff, patient, and visitor movements were actually captured by the adherence monitors, though in the second outbreak we did have monitors 24 hours a day. Round-the-clock monitoring is not feasible as a component of routine infection prevention. Its expense limits its generalizability as a tool for outbreak control, The total cost for the adherence monitors for the 10-week outbreak in 2009 was $108,000.

Eradicating MDRAB was labor-intense and expensive; however, we believe the expense was justified in preventing the striking morbidity and mortality associated with MDRAB. Further, we were able to control both epidemics without closing the ICU to admissions as is often required.36 Whereas we cannot say for certain which, if any, intervention contributed to the termination of these clusters, we believe that the engagement of a stakeholder team was key in producing a shared strategy for managing the outbreaks. We also believe that the temporal association of implementing adherence monitoring and termination of both outbreaks suggests that this strategy may be useful in certain settings – particularly those in which the ongoing transmission of an epidemic strain may be life-threatening for severely ill patients.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the intramural research program of the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center, National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

No authors report conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Weber DJ, Rutala WA, Miller MB, Huslage K, Sickbert-Bennett E. Role of hospital surfaces in the transmission of emerging health care-associated pathogens: norovirus, Clostridium difficile, and Acinetobacter species. Am J Infect Control. 2010;38:S25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2010.04.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hayden MK, Blom DW, Lyle EA, Moore CG, Weinstein RA. Risk of hand or glove contamination after contact with patients colonized with vancomycin-resistant enterococcus or the colonized patients’ environment. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29:149–54. doi: 10.1086/524331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan PC, Huang LM, Lin HC, et al. Control of an outbreak of pandrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii colonization and infection in a neonatal intensive care unit. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007;28:423–9. doi: 10.1086/513120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fournier PE, Richet H. The epidemiology and control of Acinetobacter baumannii in health care facilities. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:692–9. doi: 10.1086/500202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Villegas MV, Hartstein AI. Acinetobacter outbreaks, 1977–2000. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2003;24:284–95. doi: 10.1086/502205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aygun G, Demirkiran O, Utku T, et al. Environmental contamination during a carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii outbreak in an intensive care unit. The Journal of hospital infection. 2002;52:259–62. doi: 10.1053/jhin.2002.1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang XZ, Frye JG, Chahine MA, et al. Genotypic and phenotypic correlations of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii-A. calcoaceticus complex strains isolated from patients at the National Naval Medical Center. J Clin Microbiol. 48:4333–6. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01585-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keen EF, 3rd, Murray CK, Robinson BJ, Hospenthal DR, Co EM, Aldous WK. Changes in the incidences of multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant organisms isolated in a military medical center. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31:728–32. doi: 10.1086/653617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sebeny PJ, Riddle MS, Petersen K. Acinetobacter baumannii skin and soft-tissue infection associated with war trauma. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:444–9. doi: 10.1086/590568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Falagas ME, Karveli EA, Siempos II, Vardakas KZ. Acinetobacter infections: a growing threat for critically ill patients. Epidemiol Infect. 2008;136:1009–19. doi: 10.1017/S0950268807009478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Enoch DA, Summers C, Brown NM, et al. Investigation and management of an outbreak of multidrug-carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in Cambridge, UK. J Hosp Infect. 2008;70:109–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2008.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baran G, Erbay A, Bodur H, et al. Risk factors for nosocomial imipenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii infections. Int J Infect Dis. 2008;12:16–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harrington SM, Stock F, Kominski AL, et al. Genotypic analysis of invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae from Mali, Africa, by semiautomated repetitive-element PCR and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2007;45:707–14. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01871-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dalben MF, Oliveira MS, Garcia CP, et al. Swab cultures across three different body sites among carriers of carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa and Acinetobacter species: a poor surveillance strategy. The Journal of hospital infection. 74:395–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morgan DJ, Liang SY, Smith CL, et al. Frequent multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii contamination of gloves, gowns, and hands of healthcare workers. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 31:716–21. doi: 10.1086/653201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ling ML, Ang A, Wee M, Wang GC. A nosocomial outbreak of multiresistant Acinetobacter baumannii originating from an intensive care unit. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2001;22:48–9. doi: 10.1086/501827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi WS, Kim SH, Jeon EG, et al. Nosocomial outbreak of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in intensive care units and successful outbreak control program. J Korean Med Sci. 25:999–1004. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2010.25.7.999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dent LL, Marshall DR, Pratap S, Hulette RB. Multidrug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: a descriptive study in a city hospital. BMC Infect Dis. 10:196. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-10-196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.La Forgia C, Franke J, Hacek DM, Thomson RB, Jr, Robicsek A, Peterson LR. Management of a multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii outbreak in an intensive care unit using novel environmental disinfection: a 38-month report. Am J Infect Control. 38:259–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2009.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaul R, Burt J-A, Cork L, et al. Investigation of a Multiyear Multiple Critical Care Unit Outbreak Due to Relatively Drug-Sensitive Acinetobacter baumannii: Risk Factors and Attributable Mortality. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1996;174:1279–87. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.6.1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pillay T, Pillay DG, Adhikari M, Pillay A, Sturm AW. An outbreak of neonatal infection with Acinetobacter linked to contaminated suction catheters. J Hosp Infect. 1999;43:299–304. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6701(99)90426-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoo JH, Choi JH, Shin WS, et al. Application of infrequent-restriction-site PCR to clinical isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii and Serratia marcescens. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3108–12. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.10.3108-3112.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hartstein AI, Rashad AL, Liebler JM, et al. Multiple intensive care unit outbreak of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus subspecies anitratus respiratory infection and colonization associated with contaminated, reusable ventilator circuits and resuscitation bags. Am J Med. 1988;85:624–31. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(88)80233-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Christie C, Mazon D, Hierholzer W, Jr, Patterson JE. Molecular heterogeneity of Acinetobacter baumanii isolates during seasonal increase in prevalence. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1995;16:590–4. doi: 10.1086/647013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perencevich EN, McGregor JC, Shardell M, et al. Summer Peaks in the Incidences of Gram-Negative Bacterial Infection Among Hospitalized Patients. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008 doi: 10.1086/592698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McDonald LC, Banerjee SN, Jarvis WR. Seasonal variation of Acinetobacter infections: 1987–1996. Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:1133–7. doi: 10.1086/313441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Retailliau HF, Hightower AW, Dixon RE, Allen JR. Acinetobacter calcoaceticus: a nosocomial pathogen with an unusual seasonal pattern. J Infect Dis. 1979;139:371–5. doi: 10.1093/infdis/139.3.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manian FA, Ponzillo JJ. Compliance with routine use of gowns by healthcare workers (HCWs) and non-HCW visitors on entry into the rooms of patients under contact precautions. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007;28:337–40. doi: 10.1086/510811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Runnegar N, Sidjabat H, Goh HM, Nimmo GR, Schembri MA, Paterson DL. Molecular epidemiology of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in a single institution over a 10-year period. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:4051–6. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01208-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Touati A, Achour W, Cherif A, et al. Outbreak of Acinetobacter baumannii in a neonatal intensive care unit: antimicrobial susceptibility and genotyping analysis. Ann Epidemiol. 2009;19:372–8. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Landman D, Butnariu M, Bratu S, Quale J. Genetic relatedness of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii endemic to New York City. Epidemiol Infect. 2009;137:174–80. doi: 10.1017/S0950268808000824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wisplinghoff H, Hippler C, Bartual SG, et al. Molecular epidemiology of clinical Acinetobacter baumannii and Acinetobacter genomic species 13TU isolates using a multilocus sequencing typing scheme. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2008;14:708–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.02010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Markogiannakis A, Fildisis G, Tsiplakou S, et al. Cross-transmission of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii clonal strains causing episodes of sepsis in a trauma intensive care unit. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29:410–7. doi: 10.1086/533545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zarrilli R, Casillo R, Di Popolo A, et al. Molecular epidemiology of a clonal outbreak of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in a university hospital in Italy. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2007;13:481–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2006.01675.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schulte B, Goerke C, Weyrich P, et al. Clonal spread of meropenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii strains in hospitals in the Mediterranean region and transmission to South-west Germany. J Hosp Infect. 2005;61:356–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barnaud G, Zihoune N, Ricard JD, et al. Two sequential outbreaks caused by multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii isolates producing OXA-58 or OXA-72 oxacillinase in an intensive care unit in France. The Journal of hospital infection. 76:358–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2010.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]