Abstract

This paper proposes a theoretical framework and an empirical example of the relationship between the civic stratification of immigrants in the United States, and their access to healthcare. We use the 2007 Pew/RWJF Hispanic Healthcare Survey, a nationally representative survey of U.S. Latinos (n=2783 foreign-born respondents) and find that immigrants who are not citizens or legal permanent residents are significantly more likely to be excluded from care in both the U.S. and across borders. Legal status differences in cross-border care utilization persisted after controlling for health status, insurance coverage, and other potential demographic and socio-economic predictors of care. Exclusion from care on both sides of the border was associated with reduced rates of receiving timely preventive services. Civic stratification, and political determinants broadly speaking, should be considered alongside social determinants of population health and healthcare.

Keywords: Civic stratification, immigrant health, access to care, political determinants of health, social determinants of health

The states of the developed world all strive to control population movements across their boundaries. However, as migration benefits those moving from the developing to the developed world, migrants try to circumvent barriers to entry, doing so with at least some success. Migration control therefore yields undocumented migration. Nowhere is there an undocumented population as large as the roughly 12 million undocumented persons living in the United States, nor one where unauthorized status has proved so persistent.1 The growth and persistence of this population, lacking the full set of rights and entitlements enjoyed by legally present persons, has generated growing interest in the health consequences of undocumented status.

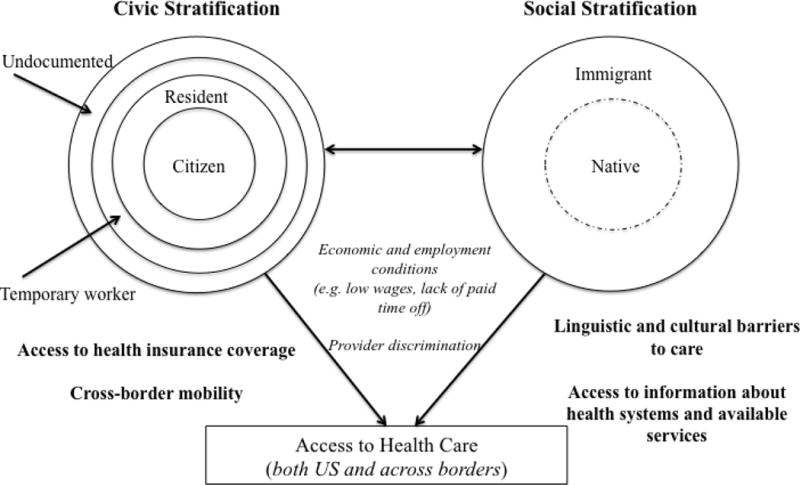

This paper develops a conceptual and empirical contribution to that literature. First, we argue for an approach that distinguishes between the specifically social and the specifically political aspects of population movements across boundaries and the determinants of population health. On the one hand, international migration generates social stratification corresponding to the informal, social differences between immigrants and natives. Immigrants arriving with expectations and patterns of behavior native to a different environment find themselves in a foreign world where they are treated like strangers who don’t belong. On the other hand, international migration also yields civic stratification (Lockwood 1996; Morris 2002), or stratification based on the formal, legal differences between citizens and various categories of non-citizens. Thus, every immigrant begins as a non-citizen moving into a legal zone that entails territorial presence but exclusion from the full complement of rights enjoyed by citizens (Bosniak 2006; Motomura 2014). Within this space, rights and entitlements vary depending on status – whether the person is an “immigrant” allowed to settle permanently, a “nonimmigrant” who is expected to remain for a delimited period of time (e.g. international students, temporary workers, or tourists), or is without authorization altogether.

Second, we demonstrate the linkage between the civic stratification of immigrants and access to health services both in and outside the United States, and the resulting delays in timely screening of preventable chronic diseases. Only citizens have the unrestricted right to move in and out of the country of citizenship as they please. While U.S. law allows permanent residents to enjoy free cross-border mobility as long as they return to the United States within a six-month period, unauthorized migrants lack the right to re-enter should they ever leave. This confinement to U.S. soil is reinforced by ever more-vigilant migration control efforts (Cornelius 2001).

These differences in cross-mobility rights – the product of civic stratification – matter because they compound the impact of the social exclusion to which all immigrants are vulnerable, regardless of legal status, including lack of familiarity with the U.S. health care system, the shortage of providers who speak their native language, and discriminatory treatment by healthcare practitioners. However, within the United States, naturalized citizens and legal permanent residents benefit from rights to care unavailable to their undocumented counterparts, a disparity accentuated by enactment of the Personal Responsibility Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PROWRA) of 1996, which expanded restrictions on access to public benefits for undocumented residents (Kullgren 2003), as well as the Affordable Care Act (ACA), which, as of 2014, has granted U.S. citizens and permanent residents the right (and responsibility) to receive health insurance coverage, while explicitly excluding undocumented immigrants from this very same entitlement (Zuckerman, Waidman and Lawton 2011).

Given their rights to cross-border mobility, citizens and permanent residents may also have access to care outside the United States (Glinos et al. 2010).2 Medical travel across the U.S.-Mexico border among Latino immigrants in the U.S., has been described as a potential response to dissatisfaction with U.S. providers as well as the cost of U.S.-based care (Wallace, Mendez-Luck and Castaneda 2009). However, among Latino immigrants lacking citizenship or permanent residence that option is largely foreclosed. As we show in the paper, these immigrants are significantly less likely to utilize cross-border care than their counterparts possessing citizenship or legal permanent residence in the U.S. We further demonstrate that access to care across borders is in turn associated with significant disparities in to the utilization of preventive services.

Migration control, civic stratification, and health care

Population movements across territorial boundaries lead to an encounter between migrants navigating an unfamiliar context and treated as outsiders, and established residents meeting strange people from abroad. The social stratification of immigrants and natives can result in considerable vulnerability for migrants, including limits on full inclusion within the U.S.-based health care system (Derose, Escarce and Lurie 2007). Over time and as migrants put down roots, those vulnerabilities tend to fade, as migrants’ quest to get ahead encourages the adoption of language, knowledge, and practices rewarded in the U.S. (Alba and Nee 2003). The literature on immigrant health and healthcare typically focuses on this growing proximity to natives or established residents, conceptualized under the labels of “acculturation”, integration, or assimilation (Lara et al. 2005).

Civic stratification and within border health care

In addition to facing social stratification, every migrant confronts civic stratification, based on the formal, political boundary between citizens and non-citizen (Lockwood 1996; Morris 2002). Citizenship fundamentally differs from the social boundary separating immigrants from natives: it is internally inclusive, entailing the same set of formal rights for all citizens regardless of nativity or other differences, but externally exclusive, starkly curtailing the rights afforded to non-citizens (Baubock 2012; Bosniak 2006; Brubaker 1992). Foreign, non-citizens are all alike in lacking the full set of rights enjoyed by citizens, but some possess a larger bundle of entitlements than others. In the U.S., legal permanent residents tend to be treated as “Americans in waiting” (Motomura 2014) and thus partake of most, but not all citizenship rights. By contrast, unauthorized migrants hold tenuous residence rights and more limited access to public services. Thus, as Jasso (2011:1292) has argued, “migration and stratification are intimately and irrevocably linked.”

Civic stratification both adds to the social stratification resulting from the differences between natives and all immigrants and also contributes to new forms of social stratification among immigrants based on legal status. Undocumented immigrants suffer most from the combined social and civic exclusion, given their firm exclusion from access to citizen rights. The social exclusions produced by the immigrant condition combine with unlawful presence and lack of documentation to shape social and economic determinants of health by limiting social and economic mobility (Bean et al. 2011), increasing exposure to exploitation, and impeding access to services for which identification is required. Legally ineligible to work and often to even drive, undocumented immigrants are limited to low-wage, often unstable work, and common experiences of wage theft (Bernhardt et al. 2009; Hall and Greenman 2015; Hall, Greenman and Farkas 2010). Those conditions in turn constrain housing options, contributing to overcrowding, food insecurity, and high levels of stress, all of which may in turn lead to adverse health outcomes for both adults and children (Hadley et al. 2008; Ortega et al. 2009; Yoshikawa 2011).

Civic stratification also compounds the impact of social stratification on access to health care (Figure 1). Undocumented status often bars immigrants from receipt of many forms of assistance at an affordable price, most notably adult primary and specialized medical care, although undocumented migrants are covered for emergency medical care and select disease-specific screening and treatment (Wallace et al, 2013). Some localities and states widen access to health care for undocumented residents (e.g. by offering coverage for prenatal care), yet even then legal restrictions imposed by other levels of government may impede access to specialized or tertiary care. Local-level efforts to reduce barriers to care also lead to a patchwork, in which undocumented immigrants living on the wrong side of a municipal boundary may find themselves deprived of a service enjoyed by their undocumented counterparts on the right side of that street (Marrow 2012).

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of the contributions of civic versus social stratification to immigrants’ access to health care both in the US and across borders

Civic stratification indirectly affects access to care by channeling many undocumented workers to informal and low-wage employment with few, if any, health benefits and levels of compensation that the prevent the purchase of private health insurance. The combination of disadvantages faced by undocumented migrants as the result of civic stratification, including reduced access to primary and other healthcare services, limited health insurance coverage, and minimal worker rights (e.g. paid time off for medical care), in turn contributes to delays in the receipt of preventive tests meant to detect and facilitate timely treatment of chronic diseases (Pourat et al. 2014; Rodriguez, Bustamante and Ang 2009).

Ironically, the advent of the Affordable Care Act is likely to increase the influence of civic stratification on access to health services in the U.S. Under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), health insurance coverage has become part of the set of rights and responsibilities that differentiate immigrants with different legal statuses. While health insurance coverage has been expanded for citizens, legal permanent residents and some others with lawfully present status, including refugees and those with temporary protected status, undocumented immigrants lack the right to purchase health insurance through government exchanges, even at full prices (Wallace et al. 2013). They also continue to be ineligible for Medicaid beyond emergency care, and, in some states, are also ineligible for covered prenatal care. Access to the benefits associated with the ACA has also been denied to young adults who were granted Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), a status that grants undocumented immigrants who arrived as children the right to work and reprieve from deportation (Raymond-Flesch et al. 2014).

Civic stratification and cross-border health care

The right to cross-border mobility is unevenly shared by residents of differing legal statuses. Only citizens possess the unqualified right to leave the country and return whenever they wish. While the state can imprison its citizens, it can neither expel them nor prevent them from re-entering the territory (Brubaker 1992). Legally present non-citizens lack that same unconditional right of re-entry: extended absence (more than six months in the case of the United States) can lead to forfeiture of authorized residence (U.S. Citizen and Immigration Services 2010). While undocumented immigrants may easily leave U.S. territory – there are frequently no entry controls going into Mexico, for example – once on the other side of the border, they can only re-enter if they manage to do so surreptitiously. Given ever-higher levels of border enforcement, entry and re-entry into the U.S. is increasingly difficult (Cornelius 2001), discouraging exit.

For persons living in developed countries like the U.S., traveling to developing countries for healthcare services is a means of taking advantage of international inequalities, since by so doing they access health services at lower costs. For immigrants, accessing care across borders may also provide a means of escaping the social exclusions encountered within the U.S. health system, including lack of access to providers who speak their native language or to the same quality of care offered to their native-born counterparts. Acquiring health care abroad has served as a safety net for immigrants encountering the gaping holes of the American medical system. Fifteen-percent of long-settled Mexican immigrants in a 2001 California study reported using medical, dental, prescription health services in Mexico the prior year (Wallace, Mendez-Luck and Castaneda 2009). Half of respondents to a 2008 survey of Texas border residents reported seeking out some form of health care in Mexico, including medical, dental, prescription drugs, or inpatient care (Su et al. 2011).

Undocumented immigrants lack the right to reenter the U.S. after exit, and therefore face greater barriers to traveling abroad for healthcare. Consequently, the political barriers to cross-border healthcare are likely to combine with the political barriers to within border care, leading to systematically reduced access to health services for undocumented residents. For example, in qualitative research with immigrants in El Paso, TX, Heyman and authors (2009) find that restricted access to care across borders compounds exclusion from regular health care in the U.S. – undocumented immigrants with acute and chronic conditions are often left to manage on their own, accepting un-prescribed medication acquired through informal networks in order alleviate pain or control diabetes. In research with members of mixed legal status families, also along the Texas border, Castañeda and Melo (2014) find that parents who are undocumented fear traveling within Texas to access care, including for their citizen children, given the risk of passing by border checkpoints. However, only one study has examined the association between legal status and cross-border care utilization in quantitative analysis. In their analysis of national-level data for Latinos in the U.S., De Jesus and Xiao (2013) found that citizenship and legal permanent residency (LPR) ‘enabled’ the utilization of cross-border care, as respondents holding these civic statuses had greater odds of using cross-border care compared to their counterparts without citizenship or LPR status. We note that with the exception of DeJesus and Xiao’s analysis of foreign-born Latinos returning to anywhere in Latin America for care, the available research has been largely limited to Mexican immigrants returning to Mexico for care.

We build on this previous work on cross-border care utilization, as well as research on legal status disparities on access to health care within the U.S. (Rodriguez, Bustamante and Ang 2009; Vargas Bustamante et al. 2012), which often does not consider the cross-border dimension. While De Jesus and Xiao (2013) explicitly focused on the impact of citizenship and status on Latino immigrants’ use of cross-border utilization, they did not investigate immigrants’ joint utilization of services within the U.S. and across borders, a crucial combination since cross-border care is an option most likely to be pursued by those immigrants most affected by the economic costs or social difficulties of obtaining care within the U.S.

In addition, we extend DeJesus and Xiao’s work by beginning to link the lack of access to care on both sides of the border to its consequences, in this case by limiting access to screening for preventable chronic disease for three of the largest individual-level contributors to overall mortality in the U.S. – high blood pressure, high blood glucose and high LDL cholesterol (Danaei et al. 2009). While previous research has linked legal status disparities in U.S.-based healthcare to differences in preventive service utilization (Pourat et al. 2014; Rodriguez, Bustamante and Ang 2009), the link between the civic stratification of health care access on both sides of the border and preventive service utilization has not been made to our knowledge.

Hypotheses

We expect that undocumented status will be associated with exclusion from health care both across borders and within the U.S. We expect that immigrants without citizenship or legal permanent residency will be significantly less likely to utilize cross-border healthcare services, and that this disparity will remain even when controlling for health insurance status and other predictors of access to care within the U.S. Conversely, we expect that legal status disparities in access to care within the U.S. will be structured in large part by access to health insurance coverage. Finally, we expect that lack of access to health care on both sides of the border will be associated with disparities in the utilization of preventive services.

Methods

Data

We use data from the Pew Hispanic Center/Robert Wood Johnson Foundation 2007 Hispanic Health Care Survey, a nationally representative telephone-based survey of both U.S. and foreign-born Latino adults living in the United States. The survey employed a stratified sampling scheme, disproportionately sampling from geographic strata based on estimated incidence of Latino households as well as Latino surname data. Interviews were conducted in English or Spanish based on the preferences of the respondent. The response rate was 46%, which is comparable to other telephone-based health surveys (e.g. CHIS, BRFSS). Our analysis is restricted to 2783 foreign-born respondents (excluding Puerto Rico).

Dependent variables

Our primary outcome variable is a three-category indicator of past-year access to care in the U.S. and Latin America. The measure combines responses to two questions about U.S. and cross-border care. The first query asks respondents “about how long has it been since you last saw a doctor or another health care provider about your health?” We grouped respondents into those who had seen a health care provider within a year and those who did not. The second question asks respondents “during the past 12 months, did you go to Mexico or any other Latin American country, for medical care, dental care, or the purchase of medicines or any kind of treatments for an illness or injury?”, with responses limited to either ‘yes’ or ‘no’.

We classified respondents into three categories: 1) those who reported having seen a medical provider in the past year, but did not report any cross-border care utilization (i.e. only received care in the U.S.); 2) those who received cross-border healthcare, whether as the only form of care or in addition to a doctor’s visit in the U.S. during the prior year; and 3) all those who had gone without a doctor’s visit in the U.S. for more than a year and who had received no cross-border care of any type during the twelve months prior to the interview. We collapsed those who received cross-border healthcare only with those who received cross-border care in combination with a doctor’s visit in the U.S. given the very small percentage of respondents who only received care outside the United States (n=66 or 2.4% of respondents).

In order to test the consequences of limited access to health care on both sides of the border on preventive service utilization we then analyzed a second set of outcome variables: 1) whether or not respondents had received a blood pressure check in the past two years, 2) whether or not they had undergone a test for blood sugar/diabetes in the past five years, and 3) whether or not they had received a cholesterol test in the past five years. The cut-offs mirror those used in other studies of immigrant disparities in preventive service utilization (Rodriguez, Bustamante and Ang 2009).

Key Independent Variable

We use a four-category measure to indicate respondents’ legal status in the U.S. These categories are based on a series of three questions asking respondents to indicate whether or not they held 1) U.S. citizenship, 2) were a legal permanent resident, or 3) held another form of government ID. Respondents who answered no to the first two questions were categorized as having neither U.S. citizenship nor LPR status. While this likely includes many individuals who are undocumented, it likely also include migrants with other statuses that allow legal residence in the U.S. and varied access to the rights and entitlements enjoyed by citizens. We therefore distinguish those who report they held some form of government ID from those who did not. For example, many Salvadorans who moved to the United States as undocumented immigrants have since obtained Temporary Protected Status (TPS), allowing for limited-term U.S. residence and employment; persons with TPS also receive a work authorization card which can be used for purposes of identification. Nevertheless, recipients of TPS are required to remain physically present in the U.S. except in special cases approved by a government representative. As eligibility for TPS and other similar “twilight statuses” (Martin 2005) is restricted, most persons arriving in the United States without authorization remain in that status and thus lack a government-issued identification card.3

Additional Independent Variables

We control for age, gender, marital status, and whether or not respondents have children under 18. Ancillary analyses indicate that very few of the respondents to the survey have spouses or children living in Latin America. Since virtually all of these close family ties are in the U.S., respondents who are married and/or have children might also be more firmly anchored in the U.S., in which case they might have stronger preferences for U.S.-based care than those without spouses/partners and/or children.

We also control for employment and education to account for differences in cross-border care that might be driven by respondents’ economic ability to travel for care. We control for respondents’ English-language proficiency, as lower proficiency is likely to generate a preference for care from Spanish-language providers, the likelihood of which is enhanced when Latin American-born persons receive care outside the United States. We include an indicator of geographic region of residence to account for differences in geographic proximity to the border, which may facilitate greater mobility for those living nearby. Immigration-related indicators include years in the U.S. and country of origin (Mexican versus Central/South American or Caribbean).

We control for self-rated health status to assess the possibility that differences in cross-border service utilization across categories of legal status might be driven by differences in health (i.e. with those who are less healthy more motivated to go across the border for care, or conversely less mobile to travel for health care services). Control for self-rated health is additionally motivated by the concern that migrants’ health may vary across legal status categories, as undocumented migrants may be selected on better health compared to those who have legal permanent residency or are naturalized citizens. Undocumented migrants are generally young, migrate to work, and face physically demanding migrant journeys, all of which may contribute to selectivity for better health among this group compared to authorize migrants. Nevertheless, studies of migrant health selectivity (Hamilton and Hummer 2011; Rubalcava et al. 2008) have not stratified analyses by migrant documentation status at entry, leaving health selectivity by legal status an open empirical question.

Finally, we include a dichotomous indicator measuring respondents’ possession of health insurance coverage at the time of the survey. We expect that differences in health insurance coverage will be one of primary pathways by which legal status is associated with disparities in past-year medical care utilization in the U.S. However, we anticipate that disparities in health insurance coverage will exercise less influence on the relationship between legal status and cross-border care utilization, as the severe impediments to returning to the United States will deter undocumented persons from leaving U.S. territory in order to receive health care abroad.

Analytic Strategy

We first report un-weighted frequencies and weighted proportions across all dependent and independent variables for foreign-born respondents. We then estimate a series of multinomial logistic regression models using the composite measure of access to care on both sides of the border as the key outcome variable, and the four-category measure of respondent legal status as the primary predictor of access to care in the U.S. and across borders. First, we present a model showing the unadjusted regression of cross-border access to care on respondent legal status. We then control for demographic characteristics as well as a number of measures that more accurately reflect the social stratification of immigrants, including English language proficiency and years spent in the U.S. Next, we control for self-rated health, adjusting for the possibility that the health selectivity of migrants by legal status drive differences in care utilization on both sides of the border. In the final model we add a control for health insurance. Given the possibility that the dynamics of cross-border care utilization may be different for Mexican migrants relative to those from other Latin American countries given the geographic proximity of Mexico to the U.S., we test an interaction term between legal status and ethno-national origin. We also test for potential heterogeneity in the relationship between legal status and access to care by U.S. region with a series of access to care models stratified by region.

As a final step, we estimate a series of logistic regression models to test the association between legal status, access to care across borders, and the three measures of preventive service utilization. Analyses incorporated the complex survey design, including the stratified sample design and weights that re-balanced the sample to reflect the national Latino population on key demographic measures, using the –svy—package in STATA (v.14.). We use multiple imputation by chained equations to account for missing data (five imputed datasets) using the –ice- command in STATA.

Results

Descriptive

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for foreign-born respondents. A complete table of descriptive statistics by legal status is available in Appendix Table A. The average age of the sample is about 42 years and there are roughly equal numbers of men and women. Less than half of respondents possess a high school diploma, and nearly two-thirds are employed. Over two-thirds of respondents reports proficiency in English or full bilingualism in English and Spanish. The sample is concentrated in the South and West, broad geographic regions that include several of the states with the largest populations of foreign-born Latinos, including California, Texas, and Florida (Brown and Patten 2014).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for foreign-born Latinos, 2007 RWJF/Pew Hispanic Healthcare Survey (n=2783)

| Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Age (in years) | 42.7 | (14.9) |

| Years in the U.S. | 17.4 | (12.9) |

|

| ||

| N (unweighted) |

% (weighted) |

|

| Socio-demographic Characteristics | ||

| Female | 1367 | (47.4) |

| Married/union | 1884 | (67.0) |

| At least one child < 18 | 1596 | (58.3) |

| High school completion/diploma or more | 1254 | (47.3) |

| Employed | 1795 | (65.6) |

| English proficient/bilingual | 961 | (36.8) |

| U.S. region | ||

| Northeast | 382 | (13.0) |

| Northcentral | 204 | (6.8) |

| South | 941 | (36.5) |

| West | 1256 | (43.7) |

| Immigration | ||

| Country of origin | ||

| Mexican | 1899 | (67.4) |

| Central/South American or Caribbean | 884 | (32.6) |

| Legal Status | ||

| Naturalized Citizen | 974 | (36.7) |

| Legal Permanent Resident | 1066 | (36.7) |

| Neither Citizen nor LPR, other gov ID | 445 | (16.1) |

| Neither Citizen nor LPR, no gov ID | 298 | (10.5) |

| Self-rated health status | ||

| Excellent/very good/good | 1712 | (62.5) |

| Fair/poor | 1071 | (37.5) |

| Access to healthcare | ||

| Health insurance coverage | ||

| No | 1150 | (41.4) |

| Yes | 1633 | (58.6) |

| Past-year doctor’s visit | ||

| No | 631 | (23.3) |

| Yes | 2152 | (76.7) |

| Went to Latin America for illness or injury in past year | 280 | (9.9) |

| Composite measure of access to care in past year | ||

| No cross-border care/no past-year doctor visit | 565 | (20.7) |

| Past year cross-border care, w or w/o past-year doctor visit | 280 | (9.9) |

| Past year doctor’s visit, w/o cross-border care | 1938 | (69.3) |

| Preventive health services | ||

| Blood pressure check in past two years | ||

| No | 657 | (24.8) |

| Yes | 2126 | (75.2) |

| Blood sugar check in past five years | ||

| No | 836 | (31.2) |

| Yes | 1947 | (68.8) |

| Cholesterol check in past five years | ||

| No | 874 | (32.9) |

| Yes | 1909 | (67.1) |

Appendix Table A.

Descriptive statistics for foreign-born Latinos by legal status, 2007 RWJF/Pew Hispanic Healthcare Survey (n=2783)

| Naturalized Citizen (n=974) |

Legal Permanent Resident (n=1066) |

Neither citizen nor LPR, with government ID (n=445) |

Neither citizen nor LPR, without government ID (n=298) |

Tests of significant difference |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean (standard deviation) |

mean (standard deviation) |

mean (standard deviation) |

mean (standard deviation) |

|||||||

| Age, y | 49.9 (16.3) | 41.5 (12.9) | 35.8 (10.6) | 33.7 (10.3) | F=174.4 | *** | ||||

| Years in the U.S. | 26.5 (13.9) | 15.2 (9.8) | 9.4 (6.5) | 7.4 (5.6) | F=418.8 | *** | ||||

|

|

||||||||||

| Socio-demographic Characteristics | N (unweighted) |

% (weighted) |

N (unweighted) |

% (weighted) |

N (unweighted) |

% (weighted) |

N (unweighted) |

% (weighted) |

||

|

|

||||||||||

| Female | 502 | (50.5) | 532 | (46.4) | 198 | (43.8) | 135 | (44.8) | χ2=8.0 | * |

| Married/union | 652 | (67.4) | 739 | (67.6) | 310 | (68.6) | 184 | (61.2) | χ2=6.9 | |

| At least one child < 18 | 414 | (46.3) | 663 | (63.2) | 322 | (72.2) | 197 | (66.0) | χ2=146.4 | *** |

| High school completion/diploma or more | 540 | (58.9) | 449 | (43.6) | 160 | (35.8) | 105 | (36.9) | χ2=71.7 | *** |

| Employed | 565 | (60.5) | 715 | (69.0) | 317 | (69.6) | 202 | (65.7) | χ2=31.0 | *** |

| English proficient/bilingual | 465 | (51.1) | 313 | (30.6) | 117 | (26.2) | 66 | (25.1) | χ2=117.7 | *** |

| U.S. region | ||||||||||

| Northeast | 162 | (15.8) | 138 | (12.3) | 50 | (9.6) | 32 | (10.7) | ||

| Northcentral | 64 | (6.1) | 74 | (6.7) | 39 | (7.8) | 27 | (8.3) | ||

| South | 335 | (36.7) | 356 | (36.5) | 153 | (37.1) | 97 | (35.0) | ||

| West | 413 | (41.4) | 498 | (44.5) | 203 | (45.5) | 142 | (46.0) | χ2=18.5 | * |

| Mexican (versus Central/South American, Caribbean) | 577 | (58.3) | 734 | (68.2) | 333 | (76.1) | 253 | (82.8) | χ2=74.2 | *** |

| Health and healthcare | ||||||||||

| Excellent/very good/good self-rated health | 614 | (63.8) | 644 | (61.9) | 266 | (60.9) | 177 | (61.1) | χ2=1.88 | |

| Health insurance coverage | 740 | (75.7) | 630 | (57.1) | 180 | (43.1) | 83 | (26.3) | χ2=293.3 | *** |

| Past-year health care | ||||||||||

| No cross-border care/no past-year U.S. doctor visit | 125 | (12.9) | 198 | (18.9) | 139 | (31.6) | 102 | (37.1) | ||

| Past year cross-border care, with or without past-year U.S. doctor visit | 123 | (13.1) | 120 | (10.4) | 17 | (4.0) | 20 | (6.0) | ||

| Past year U.S. doctor visit, without cross-border care | 726 | (73.9) | 748 | (70.7) | 289 | (64.4) | 176 | (56.9) | χ2=118.3 | *** |

| Blood pressure check, past two years | 802 | (81.6) | 825 | (75.4) | 299 | (66.0) | 198 | (66.1) | χ2=55.3 | *** |

| Blood sugar check, past five years | 771 | (78.4) | 751 | (67.0) | 269 | (60.1) | 160 | (54.6) | χ2=99.4 | *** |

| Cholesterol check, past five years | 785 | (78.9) | 734 | (67.3) | 251 | (54.2) | 142 | (44.5) | χ2=155.8 | *** |

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001

On average, respondents had lived in the United States for 17 years as of the survey. Two thirds of respondents were from Mexico and the remaining third from other Latin American countries (of those from other Latin American countries, half were from Central America, and the remaining half were from South America and the Caribbean). Over a third of respondents reported having acquired U.S. citizenship; an equivalent proportion reported having legal permanent residency (LPR) status.4 An additional 16% lacked U.S. citizenship or LPR status but reported possession of some form of government-issued ID while 10% of the sample lacked U.S. citizenship, LPR status, or a government-issued ID.

The majority of respondents reported themselves to be in good overall health. Less than 60% reported having health insurance coverage at the time of the survey. More than three-quarters of respondents reported having visited a doctor in the past year, while less than 10% of respondents reported going to Latin America for an illness or injury in the year preceding the survey. Nearly 70% of respondents reported a past-year doctor’s visit but no cross-border care, a group we classified as receiving U.S.-care only. The roughly 10% who received cross-border care were classified as receiving a mix of cross-border and US-based care, since nearly all in this group reported both kinds of care. Twenty percent of respondents reported that they did not visit the doctor in the past year in the U.S. nor had received healthcare services in Latin America. Three quarters of respondents reported receiving a blood pressure check in the past two years, while two thirds had received tests for blood sugar and blood cholesterol, respectively, in the five years prior to the survey.

Regression Results

Undocumented immigrants are excluded from access to care in the U.S. and abroad

As shown in Table 2, Model 1, non-citizens of all legal status types are much less likely than naturalized citizens to have utilized health care services in the prior year, both in the United States and across borders, absent other controls. Whether involving cross-border or within border care, the disadvantage weighs more heavily on those lacking citizenship and legal permanent residence. Nonetheless, all categories of non-citizens most sharply diverge from naturalized citizens in their level of cross-border care. Compared to naturalized citizens, legal permanent residents have 47% lower odds of past-year care utilization across borders (OR: .53; 95% CI: .36, .78) while those who had neither citizenship nor LPR status had around 85% lower odds of past-year health care utilization across borders (87% for those with a government ID, OR: .13; 95% CI: .07, .25; 85% for those with no government ID, OR: .15; 95% CI: .08, .28).

Table 2.

Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for multinomial logistic regression predicting past-year health care, foreign-born Latinos, Pew/RWJF Hispanic Healthcare Survey, 2007 (n=2783)

| Outcome 1: Ref = No cross-border care/no past-year U.S. doctor visit

| ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome 2: Past year cross-border care, with or without past-year U.S. doctor visit

| ||||||||||||

| Model 1 (Bivariate) |

Model 2 (Add Socio-demographic Characteristics) |

Model 3 (Add Self-Rated Health) |

Model 4 (Add Health Insurance) |

|||||||||

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |||||

| Legal Status (Ref = Naturalized Citizen) | ||||||||||||

| Legal Permanent Resident | .53 | ** | (.36, .78) | .67 | (.44, 1.03) | .65 | * | (.42, .99) | .66 | (.43, 1.02) | ||

| Neither Citizen nor Legal Permanent Resident, other ID | .13 | *** | (.07, .25) | .16 | *** | (.08, .32) | .15 | *** | (.07, .31) | .15 | *** | (.07, .32) |

| Neither Citizen nor Legal Permanent Resident, no ID | .15 | *** | (.08, .28) | .20 | *** | (.10, .40) | .19 | *** | (.09, .38) | .20 | *** | (.10, .41) |

| Socio-demographics | ||||||||||||

| Age | 1.01 | (1.00, 1.03) | 1.01 | (.99, 1.03) | 1.01 | (.99, 1.03) | ||||||

| Female | 2.68 | *** | (1.83, 3.91) | 2.64 | *** | (1.80, 3.87) | 2.67 | *** | (1.83, 3.93) | |||

| Married/union | 1.26 | (.83, 1.91) | 1.26 | (.83, 1.91) | 1.25 | (.81, 1.91) | ||||||

| Has at least one child ≤ 18 years | .84 | (.56, 1.26) | .86 | (.57, 1.29) | .86 | (.58, 1.30) | ||||||

| High school or more | 1.34 | (.92, 1.95) | 1.43 | (.97, 2.10) | 1.44 | (.98, 2.11) | ||||||

| Employed | .97 | (.62, 1.53) | .96 | (.61, 1.52) | .97 | (.61, 1.54) | ||||||

| English proficient/bilingual | 1.22 | (.83, 1.82) | 1.22 | (.82, 1.81) | 1.23 | (.83, 1.83) | ||||||

| Region (Ref = Northeast) | ||||||||||||

| Northcentral | .96 | (.39, 2.38) | 1.07 | (.43, 2.65) | 1.09 | (.44, 2.70) | ||||||

| South | 1.76 | (.90, 3.44) | 1.86 | (.96, 3.62) | 1.88 | (.97, 3.65) | ||||||

| West | 1.60 | (.80, 3.20) | 1.68 | (.85, 3.34) | 1.66 | (.84, 3.29) | ||||||

| Years in the U.S. | 1.00 | (.98, 1.02) | 1.00 | (.98, 1.02) | 1.00 | (.98, 1.02) | ||||||

| Mexican (Ref = Other Latin American) | 1.72 | * | (1.09, 2.71) | 1.65 | * | (1.04, 2.60) | 1.61 | * | (1.02, 2.55) | |||

| Excellent/very good/good self-rated health | .54 | ** | (.38, .78) | .53 | ** | (.37, .77) | ||||||

| Has health insurance coverage | 1.12 | (.76, 1.65) | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Outcome 3: Past year U.S. doctor visit, without cross-border care | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |||||

| Legal Status (Ref = Naturalized Citizen) | ||||||||||||

| Legal Permanent Resident | .64 | ** | (.49, .84) | .95 | (.69, 1.31) | .92 | (.67, 1.26) | 1.03 | (.74, 1.42) | |||

| Neither Citizen nor Legal Permanent Resident, other ID | .36 | *** | (.26, .49) | .66 | * | (.45, .98) | .62 | * | (.42, .92) | .74 | (.50, 1.10) | |

| Neither Citizen nor Legal Permanent Resident, no ID | .27 | *** | (.19, .38) | .50 | ** | (.32, .78) | .48 | ** | (.31, .75) | .65 | (.41, 1.03) | |

| Socio-demographics | ||||||||||||

| Age | 1.00 | (.99, 1.01) | 1.00 | (.98, 1.01) | .99 | (.98, 1.00) | ||||||

| Female | 2.86 | *** | (2.24, 3.65) | 2.86 | *** | (2.24, 3.66) | 3.00 | *** | (2.33, 3.85) | |||

| Married/union | 1.10 | (.84, 1.45) | 1.10 | (.84, 1.45) | 1.09 | (.82, 1.44) | ||||||

| Has at least one child ≤ 18 years | .80 | (.61, 1.06) | .81 | (.62, 1.08) | .80 | (.61, 1.07) | ||||||

| High school or more | 1.06 | (.83, 1.35) | 1.12 | (.87, 1.44) | 1.09 | (.84, 1.41) | ||||||

| Employed | .61 | ** | (.46, .82) | .61 | ** | (.45, .80) | .59 | *** | (.44, .79) | |||

| English proficient/bilingual | .88 | (.68, 1.15) | .87 | (.67, 1.13) | .84 | (.64, 1.09) | ||||||

| Region (Ref = Northeast) | ||||||||||||

| Northcentral | .78 | (.45, 1.35) | .87 | (.50, 1.51) | .87 | (.50, 1.52) | ||||||

| South | .63 | * | (.42, .96) | .67 | (.44, 1.01) | .72 | (.47, 1.09) | |||||

| West | 1.03 | (.67, 1.57) | 1.08 | (.71, 1.65) | 1.11 | (.73, 1.71) | ||||||

| Years in the U.S. | 1.03 | *** | (1.02, 1.05) | 1.03 | *** | (1.02, 1.05) | 1.03 | *** | (1.01, 1.04) | |||

| Mexican (Ref = Other Latin American) | .76 | (.57, 1.01) | .72 | * | (.54, .96) | .72 | * | (.54, .97) | ||||

| Excellent/very good/good self-rated health | .54 | *** | (.42, .70) | .51 | *** | (.40, .66) | ||||||

| Has health insurance coverage | 2.31 | *** | (1.78, 2.99) | |||||||||

Source: Pew/RWJ Hispanic Healthcare Survey, 2007.

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001

In model 2, which introduces controls for the effects of social stratification, including English language proficiency and years in the U.S., there is no longer a difference between legal permanent residents and naturalized citizens in levels of past-year healthcare utilization on either side of the border. By contrast, those respondents lacking both citizenship and legal permanent residency status remain less likely to have received prior health care services, whether within or across the border. Those differences persist even after controlling for self-rated health status (Model 3), although as would be expected, relatively good self-rated health is associated with lower odds of past-year health care utilization on both sides of the border.

After controlling for health insurance coverage (Model 4) there remains a significant association between lack of both citizenship and legal permanent residency and cross-border health service utilization, which is consistent with our expectations. Specifically, those who do not hold either citizenship or LPR status but hold another form of government ID are 85% less likely to report past-year healthcare utilization abroad (OR: .15, 95% CI: .07, .32) and those who do not report having any form of government ID are 79% less likely to have utilized healthcare abroad in the year prior to the survey (OR: .20, 95% CI: .10, .41). By contrast, the association between legal status and reporting a past-year doctor’s visit in the U.S. loses statistical significance after controlling for health insurance coverage.

We found no significant interaction between legal status and ethno-national origin (Mexican versus other Latin American immigrants) in the associations with past-year healthcare utilization in the U.S. or abroad (not shown), although we note the challenge of interpreting interaction effects given the small number of respondents without citizenship or LPR status who reported receiving care across borders. In Appendix Table B, we show models of cross-border access to care for residents of the South and Western regions of the U.S., respectively. There were too few respondents with neither citizenship nor LPR status in the Northeast and Northcentral U.S. who utilized cross-border care in the previous year to estimate stratified models for these regions. This suggests that patterns in the South and West are driving the results for the national sample, and underscores the importance of region of U.S. residence in structuring access to cross-border care.

Appendix Table B.

Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for multinomial logistic regression predicting past-year health care, foreign-born Latinos, Pew/RWJF Hispanic Healthcare Survey, 2007 (n=2783)

| Outcome 1, Ref = No cross-border care/no past-year U.S. doctor visit

| ||||||

| Outcome 2: Past year cross-border care, with or without past-year U.S. doctor visit

| ||||||

| South | West | |||||

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |||

| Legal Status (Ref = Naturalized Citizen) | ||||||

| Legal Permanent Resident | .54 | (.27, 1.08) | .67 | (.35, 1.27) | ||

| Neither Citizen nor Legal Permanent Resident | .05 | *** | (.02, .13) | .23 | *** | (.10, .57) |

|

| ||||||

| Outcome 3: Past year U.S. doctor visit, without cross-border care | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |||

| Legal Status (Ref = Naturalized Citizen) | ||||||

| Legal Permanent Resident | .94 | (.52, 1.69) | .86 | (.55, 1.33) | ||

| Neither Citizen nor Legal Permanent Resident | .48 | * | (.24, .93) | .68 | (.39, 1.20) | |

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001.

Notes: A. Models combine respondents without citizenship or LPR status, regardless of whether the hold another form of government ID, to improve the precision of estimates in stratified models, B. Controls for age, gender, marital status, having at least one kid under 18, education, employment, English proficiency, region of residence, ethno-national origin, years in the U.S., self-rated health status, and health insurance coverage.

Access to care on both sides of the border is associated with preventive service utilization

In Table 3 we show the results of logistic regression models estimating the associations between access to care in the U.S. and abroad and reporting a glucose test for diabetes in the previous five years.5 Analogous results for a cholesterol test in the previous five years, and a blood pressure test in the previous two years, respectively, are available as Appendices Tables C and D. We note that after controlling for demographic and health covariates, respondents who lack citizenship, LPR status, or any other form of government ID have significantly lower odds of reporting a glucose test in the previous five years (Model 1). Once we control for health insurance coverage, however, there is no longer a significant association between legal status and glucose testing (Model 2). In Model 3 we add the categorical indicator of access to care across borders. Cross-border care, either alone or in combination with a past-year doctor’s visit in the U.S. is significantly associated with significantly greater odds of reporting a glucose test in the previous five years, relative to receiving no past-year care either in the U.S. or abroad, all else equal. In Model 4, we substitute a four-category measure of access to care that separates out those who received cross-border care only in the year prior to the survey. We interpret these results with caution, given the very small sample size for respondents with cross-border care only. Nevertheless, receiving cross-border healthcare only is associated with significantly greater odds of a receiving a glucose test in the previous five years compared to those who received no care across borders, although the magnitude of the association is much smaller compared to those who also visited a doctor in the U.S. Patterns are similar for models predicting a cholesterol test in the previous five years and a blood pressure test in the previous two years, respectively, although the indicator of cross-border care only just reached non-significance in the blood pressure model (OR: 1.72, 95% CI: .99, 2.99). Again, the number of respondents who utilized cross-border care only is very small, and results using the four-category measure of access to care should be interpreted with caution.

Table 3.

Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for logistic regressions of reporting a glucose test in the past five years on legal status and access to care across borders, foreign-born Latinos, Pew/RWJF Hispanic Healthcare Survey, 2007 (n=2783)

| Model 1 | Model 2 (Add health insurance coverage) |

Model 3 (Add access to care across borders, three-category) |

Model 4 (Add access to care across borders, four category) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |||||

| Legal Status (Ref = Naturalized Citizen) | ||||||||||||

| Legal Permanent Resident | .95 | (.75, 1.21) | 1.02 | (.80, 1.30) | 1.02 | (.80, 1.31) | 1.01 | (.79, 1.30) | ||||

| Neither Citizen nor Legal Permanent Resident, other ID | .82 | (.61, 1.11) | .95 | (.70, 1.30) | 1.06 | (.77, 1.47) | 1.06 | (.77, 1.46) | ||||

| Neither Citizen nor Legal Permanent Resident, no ID | .68 | * | (.48, .95) | .84 | (.60, 1.19) | .90 | (.63, 1.30) | .91 | (.64, 1.31) | |||

| Has health insurance coverage | 2.05 | *** | (1.69, 2.50) | 1.76 | *** | (1.44, 2.16) | 1.76 | *** | (1.43, 2.16) | |||

| Three-category access to care (Ref = No cross-border care/no past-year U.S. doctor visit) | ||||||||||||

| Past year cross-border care, with or without past-year U.S. doctor visit | 3.05 | *** | (2.16, 4.31) | |||||||||

| Past year U.S. doctor visit, without cross-border care | 3.85 | *** | (3.07, 4.83) | |||||||||

| Four-category access to care (Ref = No cross-border care/no past-year U.S. doctor visit) | ||||||||||||

| Past-year cross-border care only | 1.81 | * | (1.04, 3.13) | |||||||||

| Past year cross-border care, with or without past-year U.S. doctor visit | 3.90 | *** | (2.60, 5.84) | |||||||||

| Past year U.S. doctor visit, without cross-border care | 3.86 | *** | (3.09, 4.83) | |||||||||

Note:

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001.

Notes: Controlling for age, gender, marital status, having at least one kid under 18, education, employment, English proficiency, region of residence, years in the US and ethno-national origin.

Appendix Table C.

Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for logistic regressions of reporting a cholesterol test in the past five years on legal status and access to care across borders, foreign-born Latinos, Pew/RWJF Hispanic Healthcare Survey, 2007 (n=2783)

| Model 1 | Model 2 (Add health insurance coverage) |

Model 3 (Add access to care across borders, three-category) |

Model 3 (Add access to care across borders, four category) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |||||

| Legal status (Ref= Naturalized Citizen) | ||||||||||||

| Legal Permanent Resident | .92 | (.74, 1.17) | .98 | (.77, 1.25) | .98 | (.77, 1.26) | .97 | (.76, 1.25) | ||||

| Neither Citizen nor Legal Permanent Resident, other ID | .77 | (.57, 1.03) | .89 | (.66, 1.21) | .98 | (.71, 1.34) | .97 | (.71, 1.34) | ||||

| Neither naturalized nor Legal Permanent Resident, no ID | .59 | ** | (.42, .84) | .74 | (.51, 1.07) | .80 | (.54, 1.16) | .81 | (.55, 1.18) | |||

| Has health insurance coverage | 2.10 | *** | (1.72, 2.56) | 1.83 | *** | (1.48, 2.24) | 1.82 | *** | (1.48, 2.24) | |||

| Three-category access to care (Ref = No cross-border care/no past-year U.S. doctor visit) | ||||||||||||

| Past year cross-border care, with or without past-year U.S. doctor visit | 3.42 | *** | (2.41, 4.85) | |||||||||

| Past year U.S. doctor visit, without cross-border care | 3.95 | *** | (3.13, 4.98) | |||||||||

| Four-category access to care (Ref = No cross-border care/no past-year U.S. doctor visit) | ||||||||||||

| Past-year cross-border care only | 1.79 | * | (1.03, 3.11) | |||||||||

| Past year cross-border care, with or without past-year U.S. doctor visit | 4.57 | *** | (3.02, 6.90) | |||||||||

| Past year U.S. doctor visit, without cross-border care | 3.96 | *** | (3.14, 4.99) | |||||||||

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001.

Note: Controls for age, gender, marital status, having at least one kid under 18, education, employment, English proficiency, region of residence, years in the U.S., and ethno-national origin.

Appendix Table D.

Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for logistic regressions of reporting a blood pressure check in the past two years on legal status and access to care across borders, foreign-born Latinos, Pew/RWJF Hispanic Healthcare Survey, 2007 (n=2783)

| Model 1 | Model 2 (Add health insurance coverage) |

Model 3 (Add access to care across borders, three-category) |

Model 3 (Add access to care across borders, four category) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |||||

| Legal status (Ref= Naturalized Citizen) | ||||||||||||

| Legal Permanent Resident | 1.03 | (.80, 1.32) | 1.09 | (.85, 1.39) | 1.02 | (.84, 1.40) | 1.08 | (.83, 1.39) | ||||

| Neither Citizen nor Legal Permanent Resident, other ID |

.76 | (.56, 1.04) | .86 | (.62, 1.17) | 1.06 | (.66, 1.29) | .92 | (.66, 1.28) | ||||

| Neither Citizen nor Legal Permanent Resident, no ID |

.80 | (.56, 1.14) | .96 | (.67, 1.37) | .90 | (.72, 1.53) | 1.06 | (.72, 1.54) | ||||

| Has health insurance coverage | 1.74 | *** | (1.42, 2.13) | 1.46 | *** | (1.18, 1.80) | 1.46 | *** | (1.18, 1.80) | |||

| Three-category access to care (Ref = No cross-border care/no past-year U.S. doctor visit) | ||||||||||||

| Past year cross-border care, with or without past-year U.S. doctor visit | 2.96 | *** | (2.08, 4.22) | |||||||||

| Past year U.S. doctor visit, without cross-border care | 4.12 | *** | (3.30, 5.13) | |||||||||

| Four-category access to care (Ref = No cross-border care/no past-year U.S. doctor visit) | ||||||||||||

| Past-year cross-border care only | 1.72 | (.99, 2.99) | ||||||||||

| Past year cross-border care, with or without past-year U.S. doctor visit | 3.80 | *** | (2.49, 5.81) | |||||||||

| Past year U.S. doctor visit, without cross-border care | 3.86 | *** | (3.32, 5.16) | |||||||||

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001.

Notes: Controls for age, gender, marital status, having at least one kid under 18, education, employment, English proficiency, region of residence, years in the U.S. and ethno-national origin.

Discussion

As hypothesized, these results demonstrate the impact of civic stratification on immigrants’ access to healthcare, including healthcare located in immigrants’ countries of origin. Specifically, our findings indicate that Latino immigrants who lacked both citizenship and legal permanent residency were estimated to have a significantly lower odds of access to past-year health care both in the U.S. and abroad relative to the reference group of naturalized citizens in fully adjusted models. Controls for indicators of social stratification reduce any disparity in health care access between citizens and legal permanent residents, but do not fully account for significant disadvantages in past-year healthcare utilization for those who lack citizenship or legal permanent residency. Moreover, while variables related to socio-economic characteristics – employment; years in the U.S., and gender – had a significant association with past year’s use of within border care, only gender was significantly associated with cross-border care, highlighting the importance of civic stratification.

Once we controlled for health insurance coverage, the association between legal status and past-year doctor’s visits in the U.S. only was no longer significant. Limited access to health insurance coverage has long been recognized as a contributor to differences in access to care by legal status, and the particular disadvantages faced by immigrants who are undocumented. These disadvantages persist under the Affordable Care Act (Wallace et al. 2013). Additional analyses suggest that the trends linking civic stratification and lack of access to care are largely driven by patterns in the South and West regions of the U.S., where crossing the border for healthcare is geographically feasible for those possessing citizenship or legal permanent residency. Despite proximity, residents who hold neither of these legal statuses remain blocked from access to care across borders.

Our final set of results show that access to care on both sides of the border was significantly associated with the odds of having received low-cost screenings for preventable chronic diseases. While undocumented legal status was significantly associated with lower odds of having received either a cholesterol test or a glucose test in the previous five years in reduced models, the significant association between undocumented status and preventive service utilization appears to have be explained by the disadvantages that this group faces on measures of health insurance coverage and access to cross-border health care. Even those respondents who received cross-border care only in the year prior to the survey had significantly greater odds of receiving recent tests for diabetes and cholesterol relative to those who reported no care, either in the U.S. or Latin America.

Under current policy, the gap in access to preventive services by legal status is likely to widen, and unmet need for these services is likely to be increasingly concentrated among the undocumented. While the ACA requires that health care plans provide preventive services at no cost to their members, those not eligible for coverage will not benefit from these expanded services. The exclusions under the ACA mean that unmet need for health care, including preventive services, is likely to be increasingly concentrated among undocumented immigrants. As we’ve shown, cross-border alternatives to unmet needs are unreachable for the very population that will continue to receive limited care in the U.S.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this analysis that deserve mention. For one, given the cross-sectional nature of the survey, we are only able to estimate associations, rather than determine causal processes. In particular, while we attempt to address the possibility that poor overall health –and differences in self-rated health by legal status – could be driving patterns of cross-border care seeking by controlling for self-rated health measures, we are ultimately not able to tease apart the direction of the association between healthcare utilization and self-reported health. Moreover, while the survey captures healthcare utilization over the entire year prior to the survey, the question about self-rated health is not bound by a specific time period, further complicating the possibility of assessing the direction of the association between care utilization and perceived health status. Nevertheless, we do not find evidence of systematic differences in self-rated health by legal status (Appendix Table A) and the inclusion of a self-rated health measure does not impact our overall findings.

Regions of residence in the survey are quite broadly defined, which might obscure state-by-state or local-level variation in access to health care on either side of the border. Barriers to health care for immigrants who are undocumented may vary across local and state contexts given differences in political and social climates. In cities or states that have adopted enhanced immigration enforcement efforts, immigrants who are undocumented may be less likely to access health care for fear that medical providers might report them to police (Heyman, Nunez and Talavera 2009). In addition, respondents living closer to the border may be more acutely stratified in their ability to access needed care abroad: naturalized citizens and legal permanent residents in these areas may live more fluid cross-border lives that allow them to receive medical services abroad in the event of limited access in the U.S., whereas respondents who are undocumented continue to face formidable barriers to cross-border care even in such close geographical proximity (De Jesus and Xiao 2013; Heyman, Nunez and Talavera 2009). On the other hand, Wallace and authors (2009) found significant cross-border care utilization among California residents living at long distances from the border, which is suggestive of the acute need and the significant draw of cross-border services even if they are quite far away.

Another limitation of estimating trends in legal status from survey data is that such surveys may not include respondents who are undocumented proportionate to the size of the population. It is possible that survey respondents who are undocumented may be more highly integrated (e.g. more likely to own a U.S-based telephone) and less likely to be mistrustful of unknown calls in a climate of fear of deportation and detention. One might imagine that this selective group may be less likely to avoid U.S.-based healthcare services for fear or deportation or lack of information about location and eligibility, which may mean that our estimates of exclusion from U.S.-based healthcare are lower than they might be for the “true” population of undocumented immigrants in the U.S. On the other hand, a recent analysis suggests that estimates of the foreign-born population by legal status using survey (self-report) data are comparable to residual methods that utilize administrative (non self-report) (Bachmeier, Hook and Bean 2014), which lends some confidence that this survey has captured a relatively accurate distribution of foreign-born Latinos by legal status.

We also note that the indicator of cross-border health care utilization is more vague than we would prefer given that it is inclusive of travel for dental and prescription drug care in addition to medical care. While further detail would be ideal, population surveys almost never include questions on cross-border care utilization. While increased and more detailed data collection around the use of cross-border care might shed more light on the kinds of services that immigrants travel abroad for, the point is clear that undocumented immigrants are largely excluded from receiving health care across borders.

Conclusion: A call to consider the political determinants of population health

Analyzing the 2007 Pew/RWJF Hispanic Healthcare Survey, this paper shows how civic stratification among immigrants is associated with access to healthcare across borders. Relative to naturalized citizens, Latino immigrants lacking citizenship and permanent residence experience significantly lower levels of access to health care, both within and across U.S. borders. These disparities persisted after controlling for demographic characteristics as well as those social processes – acquisition of English language proficiency and time spent in the United States – that typically yield improvement in immigrants’ socio-economic standing. While the association between legal status and within border health care utilization lost statistical significance upon controls for health insurance coverage, levels of prior year cross-border health care usage remained significantly lower among respondents lacking citizenship and legal permanent residents than among their naturalized counterparts. In turn, access to care on both sides of the border was significantly associated with the odds of having received recent preventive services.

In emphasizing the influence of civic stratification on access to health care across borders this paper highlights the potential importance of political determinants of health and healthcare. Fueled by evidence that improvements in the health status and health equity among Americans have not kept pace with massive spending on medical services and with attention increasingly directed to factors such as education, social class, racism and stigma that are conceptualized as “fundamental” causes, (Braveman, Egerter and Williams 2011; Link and Phelan 1995) research in the field of population health has increasingly focused on the social determinants of health. As conceptualized in the literature, however, the ‘social’ generally subsumes the ‘political’; politics and policies are often listed alongside the list of other fundamental causes, with little elaboration as to what these political forces might be and how they operate.

We suggest that civic stratification itself operates as a fundamental cause, affecting social and economic well-being in addition to health outcomes. Civic stratification likely also influences health in part through its impact on access to care, given that access to care both in the U.S. and abroad is structured critically by the differentiation of rights for citizens, documented non-citizens, and undocumented immigrants. The inequities in access to care created by the stratification of individuals based on their political rights may also serve as a precursor to inequities in health outcomes; while studies have not yet uncovered dramatically different health outcomes by legal status, this is likely to change over time as undocumented immigrants become increasingly settled in the U.S. and experience persistent lack of access to care, including care to diagnosis and manage chronic disease.

Looking forward, political determinants deserve the increased attention of scholars concerned with immigrant health. Future research should continue to examine the role of civic stratification in shaping health and healthcare, in addition to the ways in which civic stratification interacts with social stratification, structuring opportunities for economic mobility, and reinforcing climates that stigmatize politically unequal groups. Nevertheless, the political is a critical factor in and of itself: As international migration inherently entails movement from the political jurisdiction of the sending state to that of the receiving state, health and health inequities among international migrants are contingent on civic stratification and the differentiation of rights that it produces.

Footnotes

This study was supported by NIH grants F31-AG041694-01A1, R24-HD041022; and J.M.T. is currently supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Health & Society Scholars program at the UCSF/UC Berkeley site. The authors would like to thank Maria-Elena DeTrinidad Young and the four anonymous reviewers for their excellent suggestions.

Half of undocumented migrants in the U.S. have been in residence on U.S. soil for 13 years or more, and the median length of time spent in the U.S. has increased steadily throughout the 21st century (Passel et al. 2014).

We note that legal permanent residents with fewer than five years of residence in the country face restricted access to Medicaid, as established by PROWRA and upheld under the ACA. However, like citizens and longer-term permanent residents, they can leave and re-enter the U.S. borders at will and thus gain access to cross-border care, an option not available to undocumented residents.

Currently, a limited number of states and municipalities also provide identification cards to unauthorized immigrants. However, the first such card was not issued until 2007 (by New Haven, CT), making it highly unlikely that any of the respondents in this 2007 survey might have been able to avail themselves of such documents (The Center for Popular Democracy 2013).

By way of comparison, data from the American Community Survey two years after the Hispanic Healthcare Survey estimates that the percentage of foreign-born Latinos who were citizens ranged from 25% for those born in Mexico, 30% of Central Americans, 45% of South Americans, to about 56% of Caribbean immigrants (Gryn and Larsen 2010). Given that the Mexican-born represent the majority of this sample, the estimates of those without citizenship (and who have neither citizenship nor LPR status) are likely lower than they are for immigrants of other Latin American origin.

We note the temporal mismatch between access to care, measured as in terms of past-year doctor’s visits and cross-border healthcare, and the preventive service outcomes. We chose the cut-offs to reflect current guidelines that recommend tests for cardiovascular conditions every four to six years for healthy adults (Goff et al. 2014) and to mirror cut-off used in similar studies of legal status and preventive service utilization. Nevertheless, we re-tested models that restricted the outcome to past-year preventive services and note that the magnitude of the association between access to care and preventive service utilization is greater when using the one-year cut-off. Further, use of cross-border care only is not significantly associated with having received a cholesterol check in the past year, although it is significantly associated with having received a glucose test and a blood pressure check, respectively, in the past year.

Contributor Information

Jacqueline M. Torres, Center for Health and Community, University of California, San Francisco, School of Public Health, University of California, Berkeley

Roger Waldinger, Department of Sociology, University of California, Los Angeles.

References

- Alba Richard D, Nee Victor. Remaking the American Mainstream: Assimilation and Contemporary Immigration. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bachmeier James D, Van Hook Jennifer, Bean Frank D. Can We Measure Immigrants’ Legal Status? Lessons From Two U.S. Surveys. International Migration Review. 2014;48(2):538–66. doi: 10.1111/imre.12059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baubock Rainer. Migration and Citizenship: Normative Debates. In: Rosenblum Marc, Tichenor Daniel., editors. The Oxford Handbook of Politics and International Migration. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bean Frank D, Leach Mark A, Brown Susan K, Bachmeier James D, Hipp John R. The Educational Legacy of Unauthorized Migration: Comparisons Across U.S.-Immigrant Groups in How Parents’ Status Affects Their Offspring. International Migration Review. 2011;45(2):348–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-7379.2011.00851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernhardt Annette, Milkman Ruth, Theodore Nik, Hackathorn Douglas, Auer Mirabai, DeFilippis James, Gonzalez Ana Luz, Narro Victor, Perelshteyn Jason, Polson Diana, Spiller Michael. Broken Laws, Unprotected Workers: Violations of Employment and Labor Laws in America’s cities. New York, NY: National Employment Law Project; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bosniak Linda S. The Citizen and the Alien: Dilemmas of Contemporary Membership. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Braveman Paula, Egerter Susan, Williams David R. The Social Determinants of Health: Coming of Age. Annual Review of Public Health. 2011;32:381–98. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown Anna, Patten Eileen. Statistical Portrait of the Foreign-Born Population in the United States, 2012. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Brubaker Rogers. Citizenship and Nationhood in France and Germany. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Castañeda Heide, Milena Andrea Melo. Health Care Access for Latino Mixed-Status Families: Barriers, Strategies, and Implications for Reform. American Behavioral Scientist. 2014;58(14):1891–909. [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius Wayne. Death at the Border: Efficacy and Unintended Consequences of U.S. Immigration Control Policy. Population and Development Review. 2001;27(4):661–85. [Google Scholar]

- Danaei Goodarz, Ding Eric L, Mozaffarian Dariush, Taylor Ben, Rehm Jurgen, Murray Christopher JL, Ezzati Majid. The Preventable Causes of Death in the United States: Comparable Risk Assessment of Dietary, Lifestyle, and Metabolic Risk Factors. PLoS Medicine. 2009;8(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jesus Maria, Chenyang Xiao. Cross-border Health Care Utilization Among the Hispanic Population in the United States: Implications for Closing the Health Care Access Gap. Ethnicity and Health. 2013;18(3):297–314. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2012.730610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derose Kathryn Pitkin, Escarce José J, Lurie Nicole. Immigrants and Health Care: Sources of Vulnerability. Health Affairs. 2007;26(5):1258–68. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.5.1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glinos Irene A, Baeten Rita, Helble Matthias, Maarse Hans. A Typology of Cross-Border Patient Mobility. Health and Place. 2010;16(6):1145–55. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goff David C, Lloyd-Jones Donald M, Bennett Glen, Coady Sean, D’Agostino Ralph B, Gibbons Raymond, Greenland Philip, Lackland Daniel T, Levy Daniel, O’Donnell Christopher J, Robinson Jennifer G, Schwartz J Sanford, Shero Susan T, Jr, Smith Sidney C, Sorlie Paul, Stone Neil J, Wilson Peter WF. 2013 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Assessment of Cardiovascular Risk: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Hearth Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129:S49–S73. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437741.48606.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gryn Thomas A, Larsen Luke J. American Community Survey Briefs. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2010. Nativity Status and Citizenship in the United States: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hadley Craig, Galea Sandro, Nandi Vijay, Nandi Arijit, Lopez Gerald, Strongarone Stacey, Ompad Danielle. Hunger and Health Among Undocumented Mexican Migrants in a U.S. Urban Area. Public Health Nutrition. 2008;11(2):151–58. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007000407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall M, Greenman E. The Occupational Cost of Being Illegal: Legal Status and Job Hazard among Mexican and Central American Immigrants. International Migration Review. 2015;49(2):406–42. doi: 10.1111/imre.12090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall Matthew, Greenman Emily, Farkas George. Legal Status and Wage Disparities for Mexican Immigrants. Social Forces. 2010;89(2):491–513. doi: 10.1353/sof.2010.0082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton Todd G, Hummer Robert A. Immigration and the Health of U.S. Black Adults: Does Country of Origin Matter? Social Science & Medicine. 2011;73(10):1551–60. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman JM, Nunez GG, Talavera V. Healthcare Access and Barriers for Unauthorized Immigrants in El Paso County, Texas. Family and Community Health. 2009;32(1):4–21. doi: 10.1097/01.FCH.0000342813.42025.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasso Guillermina. Migration and Stratification. Social Science Research. 2011;40(5):1292–336. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kullgren Jeffrey T. Restrictions on Undocumented Immigrants’ Access to Health Services: The Public Health Implications of Welfare Reform. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(10):1630–33. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.10.1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara Marielena, Gamboa Cristina, Kahramanian M Iya, Morales Leo S, Hayes Bautista David E. Acculturation and Latino Health in the United States: A Review of the Literature and Its Sociopolitical Context. Annual Review of Public Health. 2005;26:367–97. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link Bruce G, Phelan Jo. Social Conditions as Fundamental Causes of Disease. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;35:80–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockwood David. Civic Integration and Class Formation. The British Journal of Sociology. 1996;47(3):531–50. [Google Scholar]

- Marrow Helen B. The Power of Local Autonomy: Expanding Health Care to Unauthorized Immigrants in San Francisco. Ethnic and Racial Studies. 2012;35(1):72–87. [Google Scholar]

- Martin David A. Twilight Statuses: A Closer Examination of the Unauthorized Population. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Morris Lydia. Managing Migration: Civic Stratification and Migrants’ Rights. London and New York: Routledge; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Motomura Hiroshi. Immigrants Outside the Law. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega Alexander N, Horwitz Sarah M, Fang Hai, Kuo Alice A, Wallace Steven P, Inkelas Moira. Documentation Status and Parental Concerns about Development in Young U.S. Children of Mexican Origin. Academic Pediatrics. 2009;9(4):278–82. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passel Jeffrey S, Cohn D’Vera, Krogstad Jens Manuel, Gonzalez-Barrera Ana. Am J Public Health. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center; 2014. As Growth Stalls, Unauthorized Immigrant Population Becomes More Settled. [Google Scholar]

- Pourat Nadereh, Wallace Steven P, Hadler Max W, Ponce Ninez. Assessing Health Care Services Used by California’s Undocumented Immigrant Population in 2010. Health Affairs. 2014;33(5):840–47. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond-Flesch Marissa, Siemons Rachel, Pourat Nadereh, Jacobs Ken, Brindis Claire D. “There Is No Help Out There and If There Is, It’s Really Hard to Find”: A Qualitative Study of the Health Concerns and Health Care Access of Latino “DREAMers”. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2014;55(3):323–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez Michael A, Vargas Bustamante Arturo, Ang Alfonso. Perceived Quality of Care, Receipt of Preventive Care, and Usual Source of Health Care Among Undocumented and Other Latinos. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2009;24(3):508–13. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1098-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubalcava Luis N, Teruel Graciela M, Thomas Duncan, Goldman Noreen. The Healthy Migrant Effect: New Findings from the Mexican Family Life Survey. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98(1):78–84. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.098418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su Dejun, Richardson Chad, Wen Ming, Pagán Jose A. Cross-Border Utilization of Health Care: Evidence from a Population-Based Study in South Texas. Health Services Research. 2011;46(3):859–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01220.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Center for Popular Democracy. Who We Are: Municipal ID Cards as a Local Strategy to Promote Belonging and Shared Community Identity. Brooklyn, NY: The Center for Popular Democracy; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Citizen and Immigration Services. International Travel as a Permanent Resident. Washington, DC: U. S. Department of Homeland Security; 2010. [Google Scholar]