Abstract

Introduction

In academia, women remain underrepresented. Our purpose was to examine differences in faculty position and professional satisfaction among academic physicians by gender.

Methods

From 2008–2012, academic faculty members at a single institution were surveyed (2008 n=737; 2010 n=1151; 2012 n=971). Outcomes included position, choice of position, professional satisfaction, and the reasons for leaving. Logistic regression was performed to compare aspects of professional satisfaction by gender.

Results

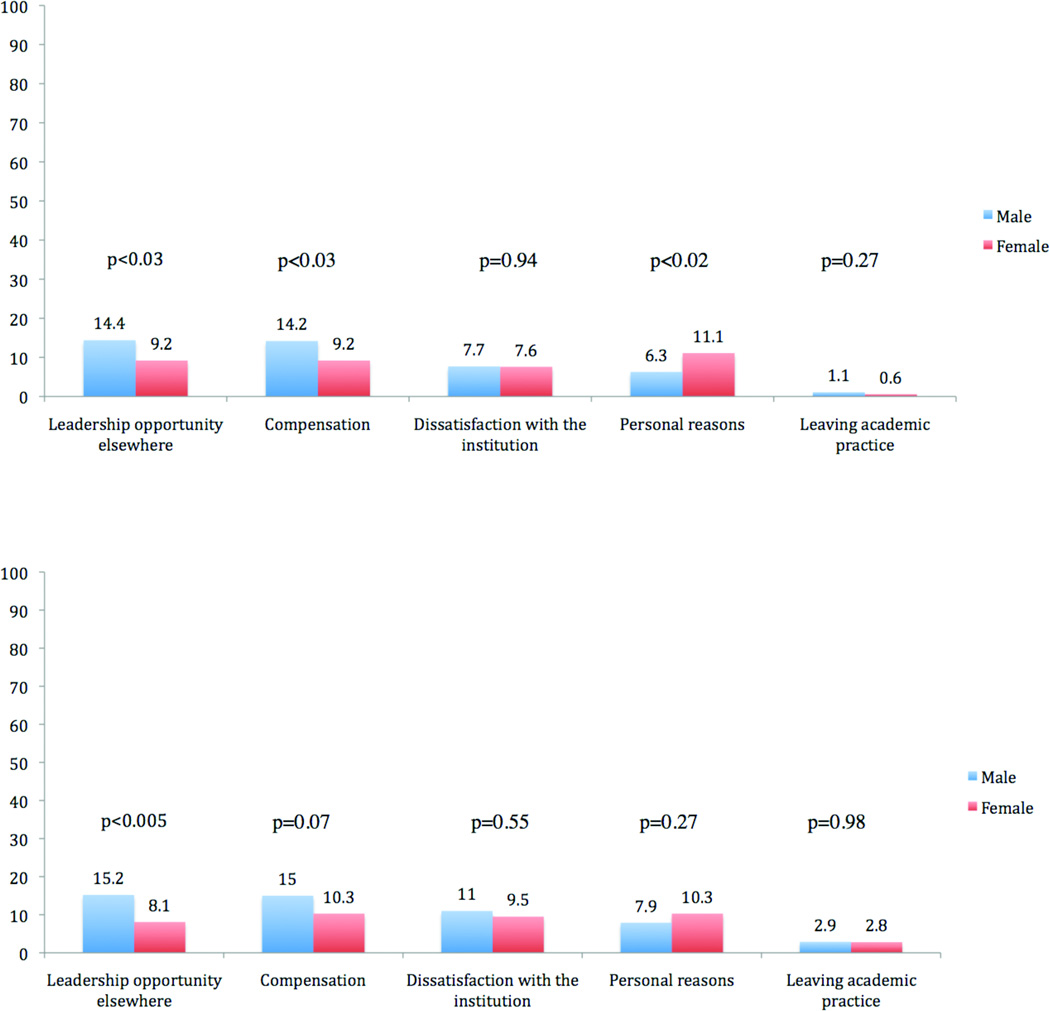

Men more often held tenure track positions compared with women (2008: 45% vs. 20%; 2010: 47% vs. 20%, 2012: 49% vs. 20%, p<0.001). Women were more likely to engage in only clinical activities compared with men (2008: 31% vs. 18%, 2010: 28% vs. 14%; 2012: 33% vs. 13%, p<0.001), and less likely to participate in research. Women chose tracks to accommodate work-life balance (2008: OR=1.9 (1.29 – 2.76); 2010: OR: 2.0 (1.38 – 2.76); 2012: OR: 2.1 (1.40 – 3.00)), and but not for the opportunity of tenure (2008: OR=0.4 (0.23 – 0.75); 2010: OR=0.5 (0.35–0.85); 2012: OR=0.5 (0.29–0.76) compared with men. Men reported higher professional satisfaction compared with women (2008: 5.7 vs. 5.4, p<0.009; 2012: 5.3 vs. 5.0, p<0.03). Men were more likely to leave due leadership opportunities (14.4% vs. 9.2%, p<0.03) and compensation (14.2% vs. 9.2%, p<0.03) compared with women.

Conclusions

Women are less satisfied in academic practice compared with men, and make choices to accommodate the demands of their work-life balance. Given the increasing pressures of academic practice, efforts to align work-life balance can improve faculty satisfaction and retention.

Keywords: academic medicine, faculty satisfaction, gender

Introduction

Young physicians are often dissuaded from entering academic practice owing to educational debt, prolonged training, early financial disincentives, and tension between research and clinical responsibilities.(1–4) Furthermore, faculty attrition remains high, and particularly affects junior and female faculty. (5,6) Dissatisfaction with aspects of both the academic and clinical environment is correlated with a desire to leave academic practice for community-based or private practice.(7,8) Therefore, identifying the causes of faculty dissatisfaction is essential in order to improve faculty retention and enhance gender diversity.

Women comprise approximately half of matriculating medical students each year. Although women enter academic practice more frequently than men, female faculty have significantly higher attrition rates. (6, 9,10) Women remain underrepresented in leadership positions, less likely to achieve promotion, and more likely to leave academic medicine. (11–13) Previous studies indicate that a lack of mentorship, unfavorable work culture, and barriers to research contribute to dissatisfaction. However, few studies have directly contrasted the factors that drive differences in job satisfaction among male and female academic physicians. (14–16)

For an academic department, faculty attrition is expensive, and the average annual cost associated with faculty turnover is approximately $400,000. Furthermore, these expenditures can compound in excess of $45 million over 5 years across an entire medical center. (17,18) In addition to financial concerns, the loss of gender diversity among faculty can weaken collaborative clinical and research efforts in women’s health. Most importantly, the lack of female faculty results in a dearth of successful female mentors and role models to encourage female medical students and residents to enter academic practice, further propagating gender inequities. Therefore, the specific aims of this study are to identify and contrast by gender 1) the decision and factors influencing the choice for type of academic faculty position 2) professional satisfaction; and 3) reasons for leaving academic practice.

Methods

Study Sample

All active faculty members at the University of Michigan Medical School were surveyed anonymously using a web-based survey during 2008, 2010, and 2012. Faculty members completed a 48-item survey regarding aspects of their current academic faculty position, professional satisfaction, and their decision to leave or remain in academic practice. We excluded faculty members who had achieved emeritus status or with adjunct/visiting faculty positions. All aspects of this study were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the University of Michigan.

Variables

We examined specific aspects of faculty positions, including rank, effort spent toward research and clinical endeavors, and appointment type. Faculty rank was categorized as assistant professor, associate professor, full professor, or other (instructor/lecturer). Activity involved included primarily clinical work, primarily research, and clinical and research evenly distributed. Faculty appointment type included the instructional, clinical, research track positions, or other (lecturer/clinical lecturer). Instructional track faculty described those faculty members who are appointed with the expectation of pursuing scholarly research, teaching, organizational service, and health care as it pertains to their professional field. Instructional track faculty are promoted primarily based on their achievements in scholarship, specifically with respect to research publications and external funding. Faculty appointed to the research track are primarily involved in scientific investigation over clinical activity, and promotion is based on achievements in mentoring, publications, external funding, and national reputation. Faculty members appointed to the clinical track are primarily responsible for patient care and trainee mentoring. Promotion is based primarily on accomplishments in clinical care and teaching, although scholarly activity and organizational service are expected as well.

Faculty were asked the reasons for choosing their track with the following yes/no options: track best suited my career decision, track was suggested by leadership, track offered the best option for work/life balance, track offered the opportunity for tenure, track did not include the pressure of tenure, not given a choice, and other. Faculty were asked to rate their overall professional satisfaction on a scale of 1 (low) to 7 (high). Additionally, faculty were asked to rate their satisfaction with academic practice (“If I had to do it all over again, I would choose a career in academics) on a scale of 1 (low) to 7 (high), and their likelihood to leave the institution (I am likely to look for appointments at other institutions in the coming 12 months) on a scale of 1 (very likely) to 7 (very unlikely). Finally, faculty were asked to describe their reasons for leaving their position with the following yes/no options: leadership opportunities elsewhere, compensation, dissatisfaction with the institution or environment, personal reasons (ex. spouse/partner seeking alternate employment), leaving academic medicine, and other.

In our analyses, we controlled for self-reported clinical specialty (medical, surgical, or hospital-based). Medical fields included dermatology, neurology, physical medicine and rehabilitation, psychiatry, emergency medicine, radiation oncology, family medicine, internal medicine, and pediatrics and communicable diseases. Surgical fields included neurosurgery, obstetrics and gynecology, ophthalmology, orthopedic surgery, general surgery, and urology. Hospital-based specialties included: anesthesiology, pathology and radiology. Finally, we controlled for ethnicity, which was categorized as “white” and “non-white.” Non-white ethnic groups consist of Arab, Asian, Black/African American, Hispanic/Latino, and multiple ethnic groups.

Statistical Analysis

Identifiers were not linked across years to protect respondent privacy, and each year of survey administration was considered as a single, cross-sectional point in time, rather than cumulative or longitudinal data. Descriptive statistics were generated for the study sample. Chi-squared analysis was used to determine demographic differences by gender. Logistic regression models were used to determine the effects of various aspects of job satisfaction on each self-report reason for choosing track. We also compared mean satisfaction scores among gender using Student’s T-test and reasons for leaving position using Chi-square test. The significance level was set at p < 0.05. Stata 11.2 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) and SPSS PASW Statistic 17.0.3 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) were used for analyses.

Results

A total of 3,003 faculty with appointments as assistant, associate or full professors were included in the study, and an average of 1,351 faculty members (45%) responded to the survey over the three years of survey administration. Table 1 illustrates the characteristics of the study sample. In each year, male faculty were more likely to be appointed to instructional track positions compared with female faculty (2008: 45% vs. 20%; 2010: 47% vs. 20%, 2012: 49% vs. 20%, p<0.001) who were more likely to be appointed to clinical track positions. Female faculty were significantly more likely to be of lower faculty rank compared with male faculty during each year of the study. For example, in 2008, 49% of female faculty were at the assistant professor level, and only 9% had achieved a rank of full professor, compared with 32% of male faculty at the assistant professor level, and 32% who had achieved a rank of full professor (p<0.001). These gaps diminished slightly by 2012, but remained significantly different (Assistant professor: 29% male vs. 42% female; Full professor: 37% male vs. 12% female, p<0.001). Female faculty were significantly more likely to report they were engaged in clinical work only during each year compared with male faculty (2008: 31% female vs. 18% male, 2010: 28% female vs. 14% male; 2012: 33% female vs. 13% male, p<0.001), and less likely to report that they participated in both clinical and research activities. There were no significant differences by specialty and ethnicity between men and women faculty members.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Faculty at the University of Michigan Medical School from 2008–2012.

| Characteristic | 2008 (n=737) |

2010 (n=1151) |

2012 (n=971) |

p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | Females | Males | Females | Males | Females | 0.009 | |

| Track§ | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Instructional | 207 (45.0) | 53 (20.0) | 227 (47.2) | 65 (20.3) | 204 (48.6) | 58 (20.3) | <0.0001 |

| Clinical | 220 (47.8) | 179 (67.6) | 218 (45.3) | 214 (66.9) | 200 (47.6) | 202 (70.6) | |

| Other | 33 (7.2) | 33 (12.5) | 36 (7.5) | 41 (12.8) | 16 (3.8) | 26 (9.1) | |

| Rank¶ | |||||||

| Assistant Professor | 149 (32.4) | 129 (48.7) | 157 (32.9) | 143 (45.3) | 121 (28.8) | 118 (41.7) | <0.0001 |

| Associate Professor | 100 (21.7) | 39 (14.7) | 101 (21.1) | 47 (14.9) | 89 (21.2) | 46 (16.3) | |

| Full Professor | 145 (31.5) | 25 (9.4) | 153 (32.0) | 39 (12.3) | 154 (36.7) | 35 (12.4) | |

| Other | 66 (14.4) | 72 (27.2) | 67 (14.0) | 87 (27.5) | 56 (13.3) | 84 (29.68) | |

| Activities involved£ | |||||||

| Clinical only | 81 (18.0) | 83 (31.1) | 68 (14.2) | 87 (27.5) | 54 (12.9) | 93 (32.9) | <0.0001 |

| Clinical and research | 377 (82.0) | 182 (68.7) | 410 (85.8) | 229 (72.5) | 366 (87.1) | 190 (67.1) | |

| Specialty† | |||||||

| Medical | 127 (27.6) | 72 (27.2) | 121 (25.3) | 96 (30.4) | 107 (25.5) | 73 (25.9) | 0.89 |

| Surgical | 126 (27.4) | 69 (26.0) | 127 (26.6) | 84 (26.6) | 119 (28.4) | 66 (23.4) | |

| Hospital-based/other | 207 (45.0) | 124 (46.8) | 230 (48.1) | 136 (43.0) | 193 (46.1) | 143 (50.7) | |

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| White | 359 (80.1) | 197 (78.0) | 361 (75.5) | 229 (72.5) | 315 (75.0) | 224 (79.2) | 0.67 |

| Non-White‡ | 89 (19.9) | 53 (21.2) | 117 (24.5) | 87 (27.5) | 105 (25.0) | 59 (20.9) | |

p<0.0001, Chi-square analysis of independence was performed to test differences between proportions in the instructional and clinical track.

Non-white ethnic groups consist of Arab, Asian, Black/African American, Hispanic/Latino, and multiple ethnic groups.

Medical: Dermatology, neurology, physical medicine and rehabilitation, psychiatry, emergency medicine, radiation oncology, family medicine, internal medicine, pediatrics and communicable diseases

Surgical: Neurosurgery, obstetrics & gynecology, ophthalmology, orthopaedic surgery, general surgery, urology

Hospital-based: Anesthesiology, pathology, radiology

Track includes faculty appointment as instructional, clinical only, research only and other (lecturer/clinical lecturer).

Rank includes full professor, assistant professor, associate professor and other (instructor/lecturer)

Activities involved include those who involved in clinical work only, involved in research only and those who involved in both clinical and research works.

Numbers do not add up because some faculty did not report their track or rank.

Table 2 describes the reasons cited by faculty for choosing their professional track, i.e. instructional (tenure) or clinical (non-tenure), stratified by gender. Female faculty were less likely compared with male faculty to report that they chose their track due to its alignment with their professional goals (2008: OR=0.52; 95%CI: 0.36 – 0.78; 2010: OR=0.57; 95%CI: 0.40 – 0.83; 2012: OR=0.86; 95%CI: 0.60 – 1.22). Female faculty were more likely to choose their track to accommodate work-life balance compared with male faculty (2008: OR=1.89; 95%CI: 1.29 – 2.76; 2010: OR: 1.95; 95%CI: 1.38 – 2.76; 2012: OR=2.05; 95%CI: 1.40 – 3.00). Additionally, female faculty were less likely to choose their track for the opportunity of tenure (2008: OR=0.42; 95%CI: 0.23 – 0.75; 2010: OR=0.54; 95%CI: 0.35–0.85; 2012: OR=0.47; 95%CI: 0.29 – 0.76), and were more likely to choose their track to avoid the pressure of achieving tenure (2010: OR=1.56; 95%CI: 1.04 – 2.43; 2012: OR=1.57; 95%CI: 1.02 – 2.43) compared with male faculty

Table 2.

| 2008 | 2010 | 2012 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio | 95%CI | p-value | Odds Ratio | 95%CI | p-value | Odds Ratio | 95%CI | p-value | |

| Best suited my professional goals | 0.52 | 0.36–0.78 | 0.001 | 0.57 | 0.40 – 0.83 | 0.03 | 0.86 | 0.60 – 1.22 | 0.39 |

| Suggested by leadership | 0.88 | 0.62 – 1.28 | 0.53 | 0.73 | 0.53 – 1.0 | 0.05 | 0.90 | 0.63 – 1.27 | 0.54 |

| Best for work-life balance | 1.89 | 1.29 – 2.76 | 0.001 | 1.95 | 1.38 – 2.76 | 0.001 | 2.05 | 1.40 – 3.00 | 0.001 |

| Opportunity for tenure | 0.42 | 0.23 – 0.75 | 0.003 | 0.54 | 0.35 – 0.85 | 0.008 | 0.47 | 0.29 – 0.76 | 0.002 |

| Did not want pressure of tenure track | 1.39 | 0.87 – 2.25 | 0.17 | 1.56 | 1.04 – 2.43 | 0.03 | 1.57 | 1.02 – 2.43 | 0.04 |

reference group is male faculty members

adjusted for ethnicity, rank, and specialty

Figure 1 illustrates overall professional satisfaction across each study year, stratified by gender. Overall, male faculty reported slightly higher professional satisfaction scores across each year, which were significantly different compared with female faculty in 2008 (5.7 vs. 5.4, p<0.009) and 2012 (5.3 vs. 5.0, p<0.03).

Figure 1.

* adjusted for rank, specialty, ethnicity, and track;

Student’s t-test was conducted for gender comparisons in each individual year.

In our sample, there were no significant differences between men and women with respect to their likelihood of leaving the institution in over the subsequent upcoming 12 months. However, there were significant differences in the reasons faculty cited for leaving by gender (Figure 2a and Figure 2b). For example, in 2010, male faculty were more likely to cite leaving for leadership positions elsewhere (14.4% vs. 9.2%, p<0.03) and due to compensation (14.2% vs. 9.2%, p<0.03) compared with female faculty. Female faculty were more likely to cite leaving for personal reasons (e.g. spouse/partner job relocation) compared with male faculty (11.1% vs. 6.3%, p<0.02). In 2012, the only significant differences by gender remained leadership opportunities elsewhere, which were more likely among male faculty (15.2% vs. 8.1%, p<0.005).

Figure 2.

Chi-square test was conducted for gender comparisons

Discussion

In this study of medical school faculty at a large public institution, female faculty were less likely to hold tenure-track positions, or fully tenured positions, compared with male faculty. Additionally, female faculty reported lower levels of professional satisfaction, and were more likely to choose their positions due to work-life balance and avoiding the pressure of achieving tenure compared with male faculty. Although male and female faculty did not differ in their likelihood of leaving their position, male faculty were more likely to leave due to leadership positions elsewhere and compensation compared to female faculty, who were more likely to leave due to personal commitments.

Previous research indicates that women are under-represented in academic medicine and systematically disadvantaged. (11–14, 19) Common barriers to success in academic practice cited by female faculty include a lack of appropriate mentorship and poor work-life balance. (15, 20) Female physicians also cite poor departmental leadership, low compensation compared with other colleagues and difficulty in professional advancement as important sources of dissatisfaction. (16) Given these obstacles, it is not surprising that women continue to lag behind men in leadership positions, publications, grant funding, and compensation in academic practice. (6,9, 21,15) Although the reasons for these persistent barriers are not entirely clear, cultural norms for men and women, such as negotiation and communication styles, may contribute to observed differences in success. For example, men are more likely to use direct tactics for negotiation (ex. direct inquiry) whereas women rely on indirect tactics (ex. demonstrating skills). (22) Additionally, differences in domestic responsibilities and expectations by gender may require more sophisticated time management skills by female faculty. Although these demands are common for women in many professions, such as business, law, and corporate management, work-life conflicts are directly correlated with physician burnout and depression, and are more commonly reported among female physicians compared with male physicians. (23, 24)

This study has several notable limitations. First, our survey was conducted at a single institution. Our observations may not be applicable to faculty at other institutions with a different infrastructure or practice model, and our study may only reflect issues and cultural differences unique to our institution. Although the survey structure was anonymous without linked identifiers, faculty may be reluctant to describe dissatisfaction and desire to leave, and approximately 53% of faculty who were surveyed did not respond. Even though the non-responder percentage comparable with previously published physician survey response rates, response rates, our results may be subject to responder bias that was not captured in our analysis. (30–33) Although we do not have information regarding the characteristics of nonresponders, the distribution of gender across faculty specialty, rank, track and ethnicity are similar to publically available distributions at our institution. Furthermore, surveys were administered anonymously during 2008, 2010, and 2012 in order to maximize candid responses regarding professional satisfaction. Therefore, each year can only be considered as a single, cross-sectional point in time, and responses cannot be analyzed cumulatively. Finally, this survey did not specifically examine proportion of faculty who sought and achieved promotion, or failed to achieve promotion, and the criteria correlated with success, such as academic and clinical productivity. Future, longitudinal, comparative studies between male and female faculty may better illuminate the barriers for women to achieve promotion and success in the academia.

Nonetheless, our findings highlight several aspects of academic medicine that could improve faculty satisfaction and, ultimately, retention. Clinical demands on faculty members have risen sharply with the inception of resident work-hour regulations, and many academic physicians report a decline in research productivity due to diminished clinical support for patient care. (25) In addition, over the last decade, financial support for research has become increasingly competitive for dwindling resources, and there is increased pressure on physicians to generate revenue for their salary through patient care. (26,27) Regulations on resident work hours have resulted in a greater clinical burden on academic faculty. (25) Despite the intellectual rewards of entering academic practice, these constant pressures accumulate, and over 30% of practicing surgeons describe feeling emotional exhaustion, and work-life balance remains elusive. (28–29) Currently, the majority of academic faculty members work approximately 80 or more hours per week. (34, 35) Though there are no accepted criteria for a “part-time” commitment, some centers have developed part-time tenure track positions with success. Part-time faculty have been shown to provide higher quality of care, greater patient satisfaction, more effective resource utilization, and greater academic productivity. (36–38) Increasing resources for family care can also ease the burdens of domestic responsibility on academic physicians. (20,39) For example, greater access to on-site child care, equitable parental leave policies, and streamlining administrative duties to weekday working hours can allow faculty the ability to meet their professional and personal responsibilities effectively. Finally, utilizing physician extenders can also improve academic and clinical productivity. These strategies could reduce clinical workloads and increase clinical support, leading to may improved satisfaction and work-life balance.

In addition to addressing work-life balance, optimizing departmental leadership can potentially improve faculty satisfaction and retention. Faculty who struggle to maintain success professionally and personally frequently look to their department leaders for mentorship and support. Although the culture in academic medicine is often described by physicians as individualistic, competitive, and hierarchical, specific initiatives can change these perceptions. (40,41) For example, University of Toronto implemented the Career Development and Compensation Program in 1995 in order to outline job expectations, enhance career development, and provide a regular peer-review process for performance evaluation. Under this model, male and female faculty advanced at similar rates. (4) In addition to clearly defining expectations, administrative leadership should have candid and constructive communication with their faculty. At the University of Virginia, a supervisory dialogue program was initiated in 2001 to provide a defined structure for faculty evaluations. Following the implementation of this program, faculty reported increased morale, a clearer vision of their personal and the institutions goals, and an improved alliance between section leaders and faculty. (43)

Finally, strong mentorship is correlated with academic productivity and retention in academic practice. (44–46) Formal mentorship programs have been shown to be successful in promoting diversity and retaining academic faculty. For example, in 1998 the Office of Women’s Health of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services implemented the National Centers of Leadership in Academic Medicine (NCLAM) designed to foster knowledge, skills, and resources for junior faculty through a structured mentoring program. (47) Following implementation, the retention of junior faculty at selected institutions increased from 58% to 80%, and retention in academia increased from 75% to 90%. (48) Although this program is largely directed toward maintaining racial and ethnic diversity among faculty, similar efforts could be successful if applied toward gender disparities.

Faculty attrition rates may differ by gender, yet all faculty have similar job desires and priorities, and identifying common criticisms among all faculty can direct resources to optimize faculty satisfaction and productivity. Strategies such as part-time tenure track positions and development programs can potentially ease the transition for graduating physicians and improve faculty retention. Ultimately, these efforts can maintain a diverse and motivated faculty who will effectively train rising physicians, provide empathic patient care, and advance knowledge through innovative medical research.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a Midcareer Investigator Award in Patient-Oriented Research (2K24 AR053120-06) to Dr. Kevin C. Chung from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, and a Mentored Clinical Investigator Award (1K08HS023313-01) to Dr. Jennifer Waljee.

References

- 1.Cain JM, Schulkin J, Parisi V, Power ML, Holzman GB, Williams S. Effects of perceptions and mentorship on pursuing a career in academic medicine in obstetrics and gynecology. Academic medicine : journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 2001;76:628–634. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200106000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borges NJ, Navarro AM, Grover A, Hoban JD. How, when, and why do physicians choose careers in academic medicine? A literature review. Academic medicine : journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 2010;85:680–686. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181d29cb9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kelly AM, Cronin P, Dunnick NR. Junior faculty satisfaction in a large academic radiology department. Acad Radiol. 2007;14:445–454. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2007.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reck SJ, Stratman EJ, Vogel C, Mukesh BN. Assessment of residents' loss of interest in academic careers and identification of correctable factors. Archives of dermatology. 2006;142:855–858. doi: 10.1001/archderm.142.7.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bickel J, Brown AJ. Generation X: implications for faculty recruitment and development in academic health centers. Academic medicine : journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 2005;80:205–210. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200503000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alexander H, Lang J. The long-term retention and attrition of U.S. medical school faculty. Association of American Medical Colleges: Aalysis in Brief. 2008;8:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bell DJ, Bringman J, Bush A, Phillips OP. Job satisfaction among obstetrician-gynecologists: a comparison between private practice physicians and academic physicians. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2006;195:1474–1478. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chung KC. Revitalizing the training of clinical scientists in surgery. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2007;120:2066–2072. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000287386.44418.35. discussion 73-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Magrane D. The changing representation of men and women in academic medicine. AAMC: Analysis in Brief. 2005;5:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nonnemaker L. Women physicians in academic medicine: new insights from cohort studies. The New England journal of medicine. 2000;342:399–405. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200002103420606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wyrzykowski AD, Han E, Pettitt BJ, Styblo TM, Rozycki GS. A profile of female academic surgeons: training, credentials, and academic success. The American surgeon. 2006;72:1153–1157. discussion 8–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalet AL, Fletcher KE, Ferdman DJ, Bickell NA. Defining, navigating, and negotiating success: the experiences of mid-career Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholar women. Journal of general internal medicine. 2006;21:920–925. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00524.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pell AN. Fixing the leaky pipeline: women scientists in academia. Journal of animal science. 1996;74:2843–2848. doi: 10.2527/1996.74112843x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carr PL, Szalacha L, Barnett R, Caswell C, Inui T. A "ton of feathers": gender discrimination in academic medical careers and how to manage it. Journal of women's health. 2003;12:1009–1018. doi: 10.1089/154099903322643938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levine RB, Lin F, Kern DE, Wright SM, Carrese J. Stories from early-career women physicians who have left academic medicine: a qualitative study at a single institution. Academic medicine : journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 2011;86:752–758. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318217e83b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lowenstein SR, Fernandez G, Crane LA. Medical school faculty discontent: prevalence and predictors of intent to leave academic careers. BMC Med Educ. 2007;7:37. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-7-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waldman JD, Kelly F, Arora S, Smith HL. The shocking cost of turnover in health care. Health care management review. 2004;29:2–7. doi: 10.1097/00004010-200401000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schloss EP, Flanagan DM, Culler CL, Wright AL. Some hidden costs of faculty turnover in clinical departments in one academic medical center. Academic medicine : journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 2009;84:32–36. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181906dff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schroen AT, Brownstein MR, Sheldon GF. Women in academic general surgery. Academic medicine : journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 2004;79:310–318. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200404000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Colletti LM, Mulholland MW, Sonnad SS. Perceived obstacles to career success for women in academic surgery. Archives of surgery. 2000;135:972–977. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.135.8.972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cropsey KL, Masho SW, Shiang R, Sikka V, Kornstein SG, Hampton CL. Why do faculty leave? Reasons for attrition of women and minority faculty from a medical school: four-year results. Journal of women's health. 2008;17:1111–1118. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stevens CK, Bavetta AG, Gist ME. Gender differences in the acquisition of salary negotiation skills: the role of goals, self-efficacy, and perceived control. J Appl Psychol. 1993;78:723–735. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.78.5.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Satele D, Sloan J, Freischlag J. Relationship between work-home conflicts and burnout among American surgeons: a comparison by sex. Archives of surgery. 2011;146:211–217. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2010.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.West CP, Shanafelt TD, Kolars JC. Quality of life, burnout, educational debt, and medical knowledge among internal medicine residents. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2011;306:952–960. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goitein L, Shanafelt TD, Nathens AB, Curtis JR. Effects of resident work hour limitations on faculty professional lives. Journal of general internal medicine. 2008;23:1077–1083. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0540-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Editors T., Dr No Money: The Broken Science Funding System. Scientific American. 2011:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lucan SC, Phillips RL, Jr, Bazemore AW. Off the roadmap? Family medicine's grant funding and committee representation at NIH. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6:534–542. doi: 10.1370/afm.911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Campbell DA, Jr, Sonnad SS, Eckhauser FE, Campbell KK, Greenfield LJ. Burnout among American surgeons. Surgery. 2001;130:696–702. doi: 10.1067/msy.2001.116676. discussion −5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: a potential threat to successful health care reform. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2011;305:2009–2010. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Asch DA, Christakis NA, Ubel PA. Conducting physician mail surveys on a limited budget. A randomized trial comparing $2 bill versus $5 bill incentives. Medical care. 1998;36:95–99. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.VanGeest JB, Johnson TP, Welch VL. Methodologies for improving response rates in surveys of physicians: a systematic review. Eval Health Prof. 2007;30:303–321. doi: 10.1177/0163278707307899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kellerman SE, Herold J. Physician response to surveys. A review of the literature. Am J Prev. Med. 2001 Jan;20(1):61–67. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00258-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Field RS, Cadoret CA, Brown ML, et al. Surveying Physicians Do Components of the "Total Design Approach" to Optimizing Survey Response Rates Apply to Physicians? Medical Care. 2002;40(7):596–605. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200207000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harrison RA, Gregg JL. A time for change: an exploration of attitudes toward part-time work in academia among women internists and their division chiefs. Academic medicine : journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 2009;84:80–86. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181900ebd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Helitzer D. Commentary: Missing the elephant in my office: recommendations for part-time careers in academic medicine. Academic medicine : journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 2009;84:1330–1332. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181b6b243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carr PL, Pololi L, Knight S, Conrad P. Collaboration in academic medicine: reflections on gender and advancement. Academic medicine : journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 2009;84:1447–1453. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181b6ac27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Palda VA, Levinson W. Commentary: the right time to rethink part-time careers. Academic medicine : journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 2009;84:9–10. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31819047bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pololi L, Kern DE, Carr P, Conrad P, Knight S. The culture of academic medicine: faculty perceptions of the lack of alignment between individual and institutional values. Journal of general internal medicine. 2009;24:1289–1295. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1131-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mizgala CL, Mackinnon SE, Walters BC, Ferris LE, McNeill IY, Knighton T. Women surgeons. Results of the Canadian Population Study. Annals of surgery. 1993;218:37–46. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199307000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bunton S. AAMC Analysis in Brief. Washington, D.C.: 2008. U.S. Medical School Faculty Job Satisfaction. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pololi L, Conrad P, Knight S, Carr P. A study of the relational aspects of the culture of academic medicine. Academic medicine : journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 2009;84:106–114. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181900efc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O'Brodovich H, Beyene J, Tallett S, MacGregor D, Rosenblum ND. Performance of a career development and compensation program at an academic health science center. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e791–e797. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rollins LK, Slawson DC, Galazka SS. Using a supervisory dialogue process in the performance management of family medicine faculty. Fam Med. 2007;39:201–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jackson VA, Palepu A, Szalacha L, Caswell C, Carr PL, Inui T. "Having the right chemistry": a qualitative study of mentoring in academic medicine. Academic medicine : journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 2003;78:328–334. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200303000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chung KC, Song JW, Kim HM, et al. Predictors of job satisfaction among academic faculty members: do instructional and clinical staff differ? Medical education. 2010;44:985–995. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03766.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bland CJ, Seaquist E, Pacala JT, Center B, Finstad D. One school's strategy to assess and improve the vitality of its faculty. Academic medicine : journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 2002;77:368–376. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200205000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mark S, Link H, Morahan PS, Pololi L, Reznik V, Tropez-Sims S. Innovative mentoring programs to promote gender equity in academic medicine. Academic medicine : journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 2001;76:39–42. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200101000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Daley S, Wingard DL, Reznik V. Improving the retention of underrepresented minority faculty in academic medicine. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2006;98:1435–1440. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]