Abstract

Circumstantial evidence alone argues that the establishment and maintenance of sex differences in the brain depend on epigenetic modifications of chromatin structure. More direct evidence has recently been obtained from two types of studies: those manipulating a particular epigenetic mechanism, and those examining the genome-wide distribution of specific epigenetic marks. The manipulation of histone acetylation or DNA methylation disrupts the development of several neural sex differences in rodents. Taken together, however, the evidence suggests there is unlikely to be a simple formula for masculine or feminine development of the brain and behaviour; instead, underlying epigenetic mechanisms may vary by brain region or even by dependent variable within a region. Whole-genome studies related to sex differences in the brain have only very recently been reported, but suggest that males and females may use different combinations of epigenetic modifications to control gene expression, even in cases where gene expression does not differ between the sexes. Finally, recent findings are discussed that are likely to direct future studies on the role of epigenetic mechanisms in sexual differentiation of the brain and behaviour.

Keywords: DNA methylation, histone, medial preoptic area, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, sex difference

1. Sexual differentiation and epigenetics

Mammalian sex determination relies on sex chromosome complement (XX versus XY), so male and female mammals are not genetically equivalent. It is worth remembering, however, that many species that come in two sexes do not have sex chromosomes, and sex is instead determined by environmental signals. For example, in many reptiles and some fish the ambient temperature during incubation determines the sex of the individual [1,2]. In other words, perfectly good male or female brains and bodies can develop from an identical genome, based on differences in the epigenetic regulation of that genome [3,4]. Similarly, although there are genetic differences between male and female mammals, many of the sex differences in mammalian brains and behaviour are likely epigenetic in origin.

There is not a single definition of epigenetic regulation, but its essence is the modulation of gene activity through changes in chromatin structure. The fundamental unit of chromatin, the nucleosome, comprises approximately 150 base pairs of DNA that wraps around an octamer of histone proteins. Adjacent nucleosomes are further packaged to different degrees, with epigenetic modifications determining the extent of compaction, accessibility to transcription factors, and rate of gene transcription [5,6]. The two best-studied types of epigenetic modifications are DNA cytosine methylation and the covalent modifications of histone tails, both of which have been linked to sexual differentiation of the brain and are the focus of this review.

Although the first studies on specific epigenetic mechanisms in brain sexual differentiation appeared less than 10 years ago [7–10], circumstantial evidence that epigenetics plays a role was available much earlier. For example, most known sex differences in the brain depend on gonadal steroid hormones, acting during a critical developmental window [11]. Soon after the testes differentiate they begin secreting testosterone. In rodents, testosterone frequently acts after being converted in the brain to an oestrogen (oestradiol) in a process known as aromatization [11]. There is often a delay between the testosterone or oestradiol exposure and emergence of a sexually dimorphic trait, suggesting a ‘memory’ for the hormone exposure; epigenetic modifications, which can be long-lived, are likely candidates for this kind of cellular memory. Second, the normal mode of sex steroid action involves epigenetic events: after binding their ligands, steroid hormone receptors recruit co-activators that themselves can modify histones (e.g. by acetylation) or that attract other proteins with histone modifying activity [12–17]. With 20/20 hindsight, it therefore seems almost inevitable that hormone-dependent sex differences in the brain would involve modifications to the epigenome, and direct tests have borne this out.

2. Role of histone acetylation in differentiation of the BNSTp and male sexual behaviour

The principal nucleus of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNSTp) and the medial preoptic area (mPOA) of the hypothalamus have been the focus of several studies on the role of epigenetic mechanisms in the development of brain sex differences. These interconnected brain regions are involved in the processing of olfactory cues and the regulation of male sexual behaviour [18–20]; the BNSTp is also an important node in the processing of stress and anxiety [21,22].

The BNSTp is larger in males than in females in adults of many species, including rats, mice, guinea pigs and humans [23–26]. In rodents, this sex difference depends on the perinatal actions of gonadal steroids and is due to differential cell death. BNSTp volume and cell number are equivalent in rats and mice of both sexes at birth [27,28]. Females have more dying cells than males during the latter part of the first postnatal week [27–29], and the volume differences emerge thereafter. The size of the BNSTp in adulthood can be masculinized in females treated with testosterone on the day of birth; oestradiol is similarly effective, suggesting that testosterone normally acts after conversion to an oestrogen [24,30]. Finally, the sex differences in BNSTp volume and cell number are eliminated in mice lacking Bax, a gene required for the death of developing neurons [26]. Thus, exposure to gonadal hormones at birth results in a sex difference in cell death in the BNSTp several days later, which causes the differences in volume and cell number seen in adults. Exactly how testosterone regulates cell death in the BNSTp is not known, however.

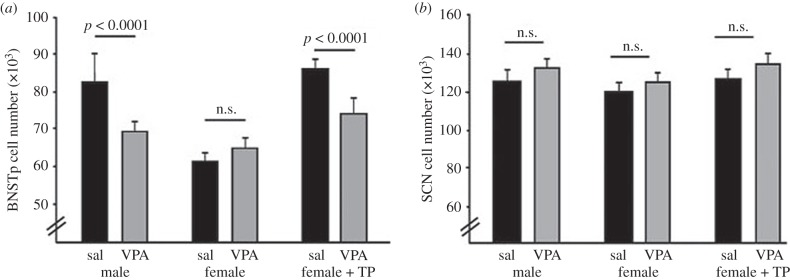

Given the role of histone acetylation in steroid hormone action, we hypothesized that this epigenetic mark might be important for sexually dimorphic BNST development. Histone acetylation is usually associated with transcriptional activation and is controlled by histone acetyltransferases and histone deacetylases (HDACs) that, respectively, add or remove acetyl groups from lysine residues of histone tails [31]. When newborn mice were treated with the HDAC inhibitor, valproic acid (VPA), histone acetylation in the brain was transiently increased [9]. Neonatal VPA treatment also prevented masculinization of BNSTp volume and cell number in both control males and testosterone-treated females (figure 1). We could exclude a non-specific effect on cell survival, because VPA did not affect cell number in the BNSTp of females, or in control brain regions [9].

Figure 1.

Neonatal treatment with the HDAC inhibitor, VPA, prevents masculinization of neuron number in the principal nucleus of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNSTp) of mice. Males, females and females treated with testosterone propionate (TP) received VPA or saline (sal) at birth and cell counts were made at weaning. (a) VPA reduced cell number in the BNSTp of males and females + TP but did not affect cell number in the BNSTp of females. (b) VPA did not affect cell number in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of any group. Adapted with permission from [9].

Although these findings supported a role for histone deacetylation in brain masculinization, VPA, like other HDAC inhibitors, has effects independent of HDAC inhibition. Work by Matsuda et al. [32] was therefore important in taking things several steps further. These investigators gave newborn male rats intracerebroventricular (icv) injections of the HDAC inhibitor trichostatin A, and also included groups treated with antisense oligonucleotides to block the endogenous production of specific HDACs. When compared to animals receiving control treatments, those receiving either the HDAC inhibitor or antisense oligonucleotides to HDACs showed marked impairments in male sexual behaviour in adulthood [32]. Thus, this and the previous study [9] are consistent in demonstrating that HDAC activity is required for masculinization, in one case of brain morphology and in the other of behaviour. Because HDACs decrease histone acetylation, which in turn would be expected to decrease gene expression, on the surface these findings suggest that masculinization requires the suppression of one or more gene(s). Neither study identified the specific gene targets, however and, as we shall see, a simplistic formula such as ‘masculinization requires gene suppression’ does not hold up.

3. DNA methylation and sexual differentiation of the brain and behaviour

The covalent addition of methyl groups to cytosine residues of DNA is catalysed by a family of enzymes known as DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs). Methylated cytosines then attract methyl-binding partners, such as methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 (MeCP2), which in turn recruit other proteins, such as HDACs, that generally act to repress transcription [33,34]. In one of the first studies to examine effects of manipulating a specific epigenetic mechanism on sexual differentiation, Kurian et al. [35] used small interfering RNAs to decrease MeCP2 expression in the amygdala of neonatal rats and measured several behaviours at weaning. Juvenile male rats normally play more than females, but neonatal treatment with MeCP2 siRNA reduced social play behaviour specifically in males, thereby eliminating the sex difference [35]. Sociability and anxiety were not affected, but also did not show sex differences. This suggests that preventing the sequelae of DNA methylation in the amygdala prevents the masculinization of play behaviour.

In the most comprehensive study on the topic to date, however, Nugent et al. [36] found a role for greater DNA methylation in females in normal, sexually differentiated development of the rat mPOA. A number of sex differences have been described in the mPOA, including the existence of a cell group that is several times larger in males, greater complexity of astrocytes in males and greater dendritic spine density in males [37–39]. All of these features are masculinized in females treated with testosterone, or an aromatized product of testosterone such as oestradiol, during a critical neonatal period; male sexual behaviour is also masculinized in such hormone-treated females [40]. In punches of the mPOA of neonatal female rats, Nugent et al. found greater DNMT activity and more fully methylated sites (90–100% of cytosines methylated) genome-wide in females than in males. Both of these sex differences were eliminated by treating newborn females with oestradiol [36], illustrating their hormone dependence.

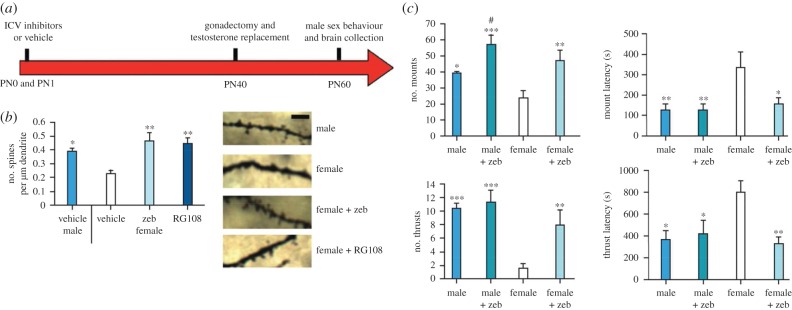

To determine whether sex differences in DNA methylation may be required for sexual differentiation of the mPOA, the investigators then administered the DNMT inhibitors, zebularine or RG108, icv to newborn rats. Neonatal DNMT inhibition masculinized dendritic spine density and copulatory behaviour of females in adulthood, with little to no effect in males (figure 2) [36]. Remarkably, DNMT inhibition on postnatal days 10 and 11 (i.e. after the critical period for sexual differentiation) also masculinized dendritic spines and at least some features of male copulatory behaviour [36]. Since DNA methylation is usually associated with transcriptional repression, this suggests that normal female brain morphology and behaviour involve the active repression of masculinization, an interesting twist on the traditional view that female development is the ‘passive,’ or default, mode.

Figure 2.

Neonatal DNMT inhibition masculinizes dendritic spine density in the mPOA and male copulatory behaviour in rats. (a) Newborn rats were treated with vehicle or a DNMT inhibitor, zebularine (zeb) or RG108, on postnatal day (PN) 0 and 1; all animals were gonadectomized and given hormone replacement at PN40, and behaviour testing and brain collection were performed in adulthood (PN60). (b) Dendritic spine density at PN60 is greater in control males than in control females and treatment with zebularine or RG108 masculinized spine density in females. (c) Male copulatory behaviours (mounts and thrusts) were also masculinized in DNMT-treated females. Adapted with permission of Nature Publishing from [36]. (Online version in colour.)

4. Do the studies to date contradict each other?

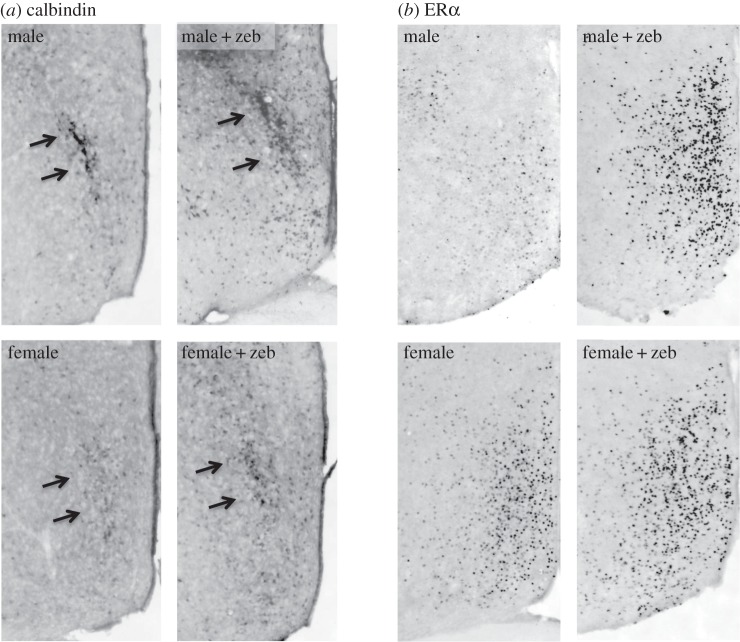

The histone acetylation and DNA methylation studies described above seem to give conflicting messages about whether repression or activation of gene expression is associated with masculinization of the brain and behaviour. If we accept at face value that both HDAC inhibition and DNMT inhibition increase gene expression, then findings could be summarized as in table 1. It is possible, of course, that effects of a specific epigenetic manipulation may vary by age, species or brain region. Recent data from our laboratory suggest that such effects even vary by dependent measure within a brain region. For example, in the mPOA of mice, males have more cells expressing the calcium-binding protein calbindin, but females have more cells expressing oestrogen receptor α [42,43]. We treated newborn mice, icv, with the DNMT inhibitor zebularine or vehicle, and examined effects on expression of these two proteins after weaning. Our preliminary findings [41] indicate that neonatal treatment with zebularine increases both the number of calbindin cells and oestrogen receptor α cells in the mPOA (figure 3) [41]. While the changes are in the expected direction for a DNMT inhibitor (decreased DNA methylation leading to increased gene expression), expression is pushed in the ‘masculine’ direction in one case (calbindin) and in the ‘feminine’ direction in the other.

Table 1.

Effects of manipulating histone acetylation or DNA methylation on sexually dimorphic endpoints.

| epigenetic manipulation | predicted overall effect | outcome | measure | reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ↑histone acetylation | ↑gene expression | ↓masculinization (males only) | volume and cell number—BNST | [9] |

| ↑histone acetylation | ↑gene expression | ↓masculinization | male sex behaviour | [32] |

| ↓DNA methylation | ↑gene expression | ↑masculinization (females only) | dendritic spines—mPOA | [36] |

| ↓DNA methylation | ↑gene expression | ↑masculinization (females only) | male sex behaviour | [36] |

| ↓DNA methylation | ↑gene expression | ↑masculinization (both sexes) | calbindin cell number—mPOA | [41] |

| ↓DNA methylation | ↑gene expression | ↓masculinization (males only) | oestrogen receptor α cell number—mPOA | [41] |

Figure 3.

Calbindin and oestrogen receptor α immunoreactivity (ERα-ir) in the mPOA at weaning in male and female mice that received saline or zebularine (zeb) on the day of birth. (a) Control males have more calbindin-ir; neonatal DNMT inhibition significantly increased calbindin-ir in both sexes, but did not eliminate the sex difference. (b) Control females have more ERα-ir than males; neonatal DNMT inhibition increased ERα-ir in males and eliminated the sex difference [41].

More to the point, however, it is probably too simplistic to think of histone deacetylation and DNA methylation as repressing transcription, or HDAC inhibitors and DNMT inhibitors as increasing transcription. First, there are many examples where DNA methylation or histone deacetylation of a specific gene increases transcription [44–46]. Second, in contrast to what one might think, treatment of normal cells with an HDAC or DNMT inhibitor alters the expression of only a few per cent of all genes [36,47,48], with expression of some going up and others going down. In other words, these are not sledgehammer approaches that globally increase all gene expression. Although it is not known what makes a given gene susceptible to an HDAC or DNMT inhibitor, one suggestion is that genes actively undergoing regulation may be particularly affected [48,49].

Thus, the foregoing studies [9,32,35,36] are important in showing a requirement for epigenetic modifications in sexually differentiated development of brain and behaviour. However, we may not know what needs to be repressed or activated until specific gene cascades are identified and, even then, the answer is likely to be complex and region- or even variable-specific. In a complementary—in some ways opposite—approach, several recent studies have taken a broad view by conducting whole-genome analyses of epigenetic marks in the male and female brain.

5. Whole-genome studies of sex differences in epigenetic mechanisms

The past 2 years have seen the publication of at least five genome-wide studies of sex differences in specific epigenetic marks in the brain [36,50–53].

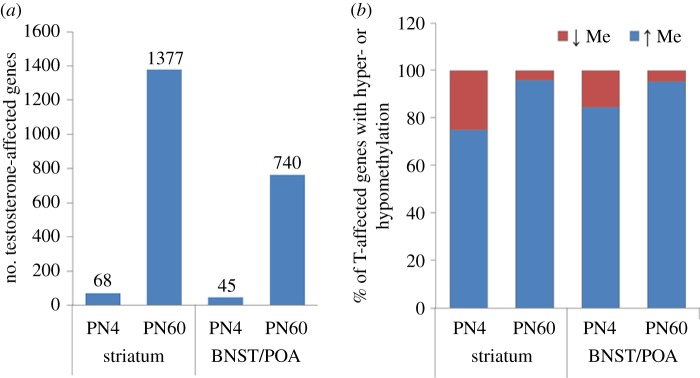

Ghahramani et al. [50] used reduced representation bisulfite sequencing to examine the programming (or organizational) effects of neonatal testosterone on the DNA methylome and transcriptome of the mouse brain. Brains were collected on postnatal day 4 or in adulthood from control males, control females or females treated with testosterone on the day of birth, and the BNST/mPOA and striatum were microdissected from all animals. To ensure that group differences were not due to different levels of circulating hormones at the time of sacrifice, mice killed as adults were gonadectomized prior to puberty and given capsules designed to produce equivalent, male-like levels of testosterone in all animals. The ambitious design of this study generated a large amount of data, with at least four interesting take-home messages.

First, effects of neonatal testosterone on the methylome were late emerging. At P4, there were very few genes (fewer than 70) with an effect of neonatal testosterone exposure (females versus females plus testosterone) or with a sex difference (males versus females) in DNA methylation. By adulthood, however, 700–1400 genes had significant testosterone- or sex-dependent differences in methylation in the striatum and BNST/mPOA (figure 4) [50]. Thus, hormone exposure at birth led to differences in DNA methylation, most of which emerged well after birth.

Figure 4.

(a) Treatment of female mice with testosterone on postnatal day (PN) 0 influences DNA methylation in a small number of genes at PN4, but many more at PN60 in both the striatum and BNST/POA. (b) Most of the genes affected by neonatal testosterone treatment of female mice showed increased (hyper-) methylation (blue) relative to that in control females. This was seen at both ages and in both brain regions [50]. (Online version in colour.)

A second finding from this study was that the differentially methylated genes were unevenly distributed: between 85 and 90% of the genes that were differentially methylated in females versus testosterone-treated female mice had less methylation in the female group (figure 4). This was true at both ages and in both brain regions, and was also seen in the female versus male comparison (i.e. most genes with a sex difference were hypomethylated in females) [50]. Similarly, a study of the DNA methylome during human fetal brain development identified about 60 genes, or genomic sites, with a significant sex-by-age interaction in DNA methylation; of these, most sites showed progressive hypomethylation in females beginning at approximately 100 days gestation [51]. Because the prenatal testosterone surge in humans occurs from about 70–125 days gestation [54,55], the relative hypomethylation in females coincides with the differential exposure to testosterone in males and females.

A third major message from the Ghahramani et al. [50] study was that the striatum and BNST/mPOA showed similar patterns and, if anything, there were more sex differences in DNA methylation in the striatum. Although sex differences have been described in the striatum, it is not as overtly dimorphic as the BNST/mPOA. This suggests that at the level of control of gene expression, sex differences are not limited to brain regions we traditionally think of as very dimorphic. This may be related to the final take-home message, which is that most genes with a sex difference in DNA methylation were not differentially expressed [50]. In some ways, this may actually be the most interesting outcome, especially when combined with the sex bias in differentially methylated genes because it suggests that males and females may use different epigenetic mechanisms to achieve the same outcome in terms of gene expression.

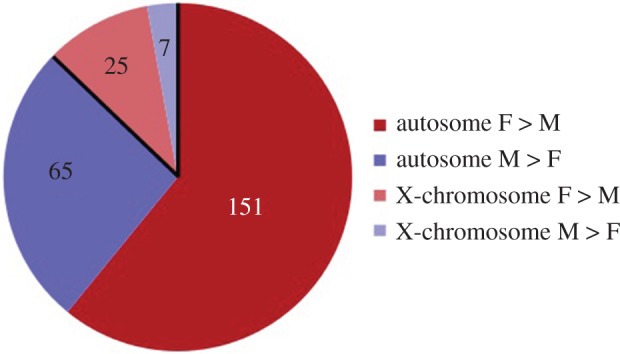

A similar conclusion was reached by our recent study using chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by deep sequencing (ChIP-Seq) to examine the genome-wide distribution of H3K4me3 (the addition of three methyl groups to lysine residue 4 of histone 3) in the BNST/mPOA of adult male and female mice [52]. This histone modification is of particular interest because it is highly enriched at transcription start sites of active genes, or of genes poised for activity [56–58]. While the large majority of genes had very similar H3K4me3 profiles in males and females, profiles differed significantly for about 250 genes. Of these, the majority (approx. 75%) had greater H3K4me3 in females, and this was seen whether the sex chromosomes or autosomes were considered (figure 5). Also, as in [50], sex differences in H3K4me3 did not map closely onto gene expression [52]. Genes with greater H3K4me3 in females were significantly associated with synapse structure and function; the expression of such genes is presumably tightly regulated in both sexes, but males and females may do it differently.

Figure 5.

The distribution of genes with differential H3K4me3 in the BNST/POA of adult mice showed a sex bias; most of the genes had more of this histone mark in females than in males (red and pink shading). This was true for both autosomal and X-chromosome genes [52]. (Online version in colour.)

Taken together, the findings suggest sex biases in the use of epigenetic marks to control gene expression. Such biases could come about if, for example, gonadal steroids control the expression of enzymes involved in placing or removing particular epigenetic marks, as was seen for DNMT activity in the mPOA in the study mentioned above [36]. Predispositions to use particular epigenetic mechanisms could also result from sex chromosome complement. In every cell of females, and in no cells of males, one X chromosome is inactivated. This occurs via countless epigenetic modifications of the silenced chromosome that must be continually maintained [59,60]. If any of the epigenetic machinery involved in X chromosome inactivation is rate-limiting, this creates an uneven playing field for regulating the expression of autosomal genes [61,62]. Thus, for any given epigenetic modification, the majority of differences between the sexes genome-wide may actually serve a compensatory role, i.e. to prevent differences in expression that would occur otherwise [63]. Sex biases in the use of epigenetic modifications could be clinically important because they would render the sexes differentially vulnerable to drugs or diseases that disrupt a particular epigenetic mechanism.

6. New rules for studies of epigenetic mechanisms in brain sexual differentiation

In the past few years, research findings have forced revisions to several cherished epigenetic concepts that are likely to impact the design of future studies on the epigenetics of sexual differentiation.

(a). It is not just CpG any more

Until recently, the dogma held that DNA methylation in mammals is restricted to cytosine nucleotides adjacent to a guanine nucleotide (CpGs). As such, investigators typically restricted their analyses to CpG sites, and often to a subset of selected CpGs (e.g. in promoter regions). It is now clear, however, that cytosines followed by A, C or T nucleotides can also be methylated in mammalian cells, and that this non-CpG methylation correlates with gene repression [64]. This finding is particularly relevant to neuroscience, because neurons show the highest levels of non-CpG methylation of any known mammalian cell type: roughly 50% of all DNA methylation in adult human neurons and 25% in adult mouse neurons is non-CpG [64–66]. Future studies on the epigenetics of brain sexual differentiation will undoubtedly have to take this into account.

(b). Mechanisms for demethylation are now established

Originally, DNA methylation was viewed as a permanent event. Methyl marks can indeed be long lasting, which accounts for the stable differentiation of cell types, but it has been clear for some time that DNA methylation (as well as histone modifications) in the brain dynamically change with age, learning and other factors [67–69]. The mechanism for such changes has been somewhat mysterious because there was no known demethylase, but recent work convincingly describes a mechanism for DNA demethylation involving hydroxymethylation of cytosine residues as an intermediary [70]. Interestingly, hydroxymethylation is more prevalent in the brain than in any other tissue [66,70]. As yet, we are not aware of any studies of sex differences in brain hydroxymethylation, but this is surely just around the corner.

(c). The question of site-by-site fidelity

Cells of the same type do not all have exactly the same pattern of DNA methylation. Under steady-state conditions, a population of cells may maintain average per cent methylation at a given gene region, but exactly which cytosines are methylated changes through an apparently stochastic process [71]. Indeed, it has been argued that no known DNMT has sufficient specificity to maintain site-by-site fidelity in methylation [72]. Many of us in the field of behavioural neuroscience first became aware of epigenetics through landmark papers showing DNA methylation changes to single CpG sites in a specific gene that could account for a behavioural and neuroendocrine phenotype [73]. This is likely to be the exception rather than the rule. Evidence suggests that only rarely do differences in DNA methylation at a single site relate to measureable differences in gene expression. In a recent whole-genome study of sex differences in DNA methylation in the human prefrontal cortex, for example, about 6% of the CpG sites that were differentially methylated in men and women correlated with a sex difference in transcription [53]. The odds get a little better going in the other direction: starting with a significant sex difference in gene transcription, a significant difference in DNA methylation was found about 35% of the time (but even then, only three-fourths of those were in the predicted direction) [53]. Taken together, the data suggest that rather than a focus on individual methylation events, it may be useful to think about ‘methyl tone’ or ‘acetyl tone’ in a given cell or gene region, much as we would use terms such as ‘GABAergic tone’ or ‘glutamatergic tone.’

(d). Accounting for cellular heterogeneity

Most of the sex differences in epigenetic marks found in the brain so far have been relatively subtle (i.e. 20% or fewer differences between males and females for individual genes) [36,50,52,67]. One reason for this is almost certainly the reliance on brain homogenates, which contain a multitude of cell types. Sex differences in epigenetic regulation that are cell type-specific will be masked in studies relying on homogenates (essentially, all studies to date), owing to the absence of a difference in other cells comprising the sample. A few studies have surveyed epigenetic marks in the brain following cell sorting to separate neurons from non-neurons; as might be predicted, very different patterns of age-related epigenetic changes are seen in neuronal versus non-neuronal cells (e.g. [74,75]). This is a relatively crude division, however. More refined analyses in which different subtypes of neurons are compared in the male and female brain have not yet been performed, in large part because of the amount of tissue required (the cell sorting papers cited above were conducted on human cortex, which permits a large volume of starting material). The development of techniques for quantifying the use of specific epigenetic marks, by specific genes, within specific cell types would do for the study of brain epigenetics what immunocytochemistry and in situ hybridization did for studies of gene expression in the brain. Until such techniques are available, we are likely to continue to see sex differences of underwhelming magnitude, and the interpretation of every study on sex differences in brain epigenetics must take this limitation into account.

7. What will the future bring?

Sixteen years ago, Strahl & Allis [76] coined the term ‘histone code’ to capture the idea that multiple histone modifications act in combination to regulate chromatin structure and gene transcription. Inherent in the concept was the suggestion that if we just learned to decipher the code, we could ‘read out’ expression levels for a given gene region. However, each year brings the identification of new epigenetic modification sites, and new molecules interacting with these sites. The ‘epigenetic code’ becomes more and more complex, and it sometimes seems that we are farther than ever from a fluent reading of it. In addition, the brain may be thought of as a mosaic of sex differences and sex similarities [77], and there is likely to be a mosaic of mechanisms, including epigenetic mechanisms, underlying sexual differentiation of neural structures.

Given all of the complexity in both fields, what will the future bring? Although it is hard to know, I feel fairly confident making two predictions. First, more investigators will be studying sex differences in the brain. The new National Institutes of Health initiative to balance the sex of animals and cells in preclinical research (NIH Notice: NOT-OD-15-102) will lead to the identification of new brain sex differences along with an influx of new investigators with fresh perspectives. Second, it seems inevitable that computational and statistical methods will play an ever-increasing role in those studies with an epigenetic component. The new field of computational epigenetics [78] holds some promise for dealing with the enormous combinatorial complexity of epigenetic mechanisms; the hope is that these tools may point us to new, testable hypotheses and allow for progress not possible using traditional approaches alone.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Morgan Mosley, Alexandra Castillo-Ruiz and Geert de Vries for feedback on an earlier draft of the manuscript. Morgan Mosley also generously shared her preliminary zebularine data, for which I am grateful.

Competing interests

The author has no competing interests.

Funding

This study was financially supported by NIMH R01-068482.

References

- 1.Crews D. 1996. Temperature-dependent sex determination: the interplay of steroid hormones and temperature. Zool. Sci. 13, 1–13. ( 10.2108/zsj.13.1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Merchant-Larios H, Díaz-Hernández V. 2013. Environmental sex determination mechanisms in reptiles. Sex. Dev. 7, 95–103. ( 10.1159/000341936) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matsumoto Y, Buemio A, Chu R, Vafaee M, Crews D. 2013. Epigenetic control of gonadal aromatase (cyp19a1) in temperature-dependent sex determination of red-eared slider turtles. PLoS ONE 8, e63599 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0063599) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Piferrer F. 2013. Epigenetics of sex determination and gonadogenesis. Dev. Dyn. 242, 360–370. ( 10.1002/dvdy.23924) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Felsenfeld G, Groudine M. 2003. Controlling the double helix. Nature 421, 448–453. ( 10.1038/nature01411) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jiang Y, et al. 2008. Epigenetics in the nervous system. J. Neurosci. 28, 11 753–11 759. ( 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3797-08.2008) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kurian JR, Forbes-Lorman RM, Auger AP. 2007. Sex difference in MeCP2 expression during a critical period of rat brain development. Epigenetics 2, 173–178. ( 10.4161/epi.2.3.4841) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsai HW, Grant PA, Rissman EF. 2009. Sex differences in histone modifications in the neonatal mouse brain. Epigenetics 4, 47–53. ( 10.4161/epi.4.1.7288) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murray EK, Hien A, de Vries GJ, Forger NG. 2009. Epigenetic control of sexual differentiation of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis. Endocrinology 150, 4241–4247. ( 10.1210/en.2009-0458) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCarthy MM, et al. 2009. The epigenetics of sex differences in the brain. J. Neurosci. 29, 12 815–12 823. ( 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3331-09.2009) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCarthy M, De Vries G, Forger N. 2009. Sexual differentiation of the brain: mode, mechanisms and meaning. In Hormones, brain and behavior, vol. 3 (eds Pfaff D, Arnold AP, Etgen AM, Fahrbach SE, Rubin RT), pp. 1707–1744. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spencer TE, et al. 1997. Steroid receptor coactivator-1 is a histone acetyltransferase. Nature 389, 194–198. ( 10.1038/38304) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu J, Li Q. 2003. Review of the in vivo functions of the p160 steroid receptor coactivator family. Mol. Endocrinol. 17, 1681–1692. ( 10.1210/me.2003-0116) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kishimoto M, Fujiki R, Takezawa S, Sasaki Y, Nakamura T, Yamaoka K, Kitagawa H, Kato S. 2006. Nuclear receptor mediated gene regulation through chromatin remodeling and histone modifications. Endocrine J. 53, 157–172. ( 10.1507/endocrj.53.157) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kininis M, Chen BS, Diehl AG, Isaacs GD, Zhang T, Siepel AC, Clark AG, Kraus WL. 2007. Genomic analyses of transcription factor binding, histone acetylation, and gene expression reveal mechanistically distinct classes of estrogen-regulated promoters. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 5090–5104. ( 10.1128/MCB.00083-07) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tetel MJ. 2009. Nuclear receptor coactivators: essential players for steroid hormone action in the brain and in behaviour. J. Neuroendocrinol. 21, 229–237. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2009.01827.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Auger AP, Jessen HM. 2009. Corepressors, nuclear receptors, and epigenetic factors on DNA: a tail of repression. Psychoneuroendocrinology 34, S39–S47. ( 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.05.012) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Claro F, Segovia S, Guilamón A, Del Abril A. 1995. Lesions in the medial posterior region of the BST impair sexual behavior in sexually experienced and inexperienced male rats. Brain Res. Bull. 36, 1–10. ( 10.1016/0361-9230(94)00118-K) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coolen LM, Peters HJ, Veening JG. 1997. Distribution of Fos immunoreactivity following mating versus anogenital investigation in the male rat brain. Neuroscience 77, 1151–1161. ( 10.1016/S0306-4522(96)00542-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Veening JG, Coolen LM. 2014. Neural mechanisms of sexual behavior in the male rat: emphasis on ejaculation-related circuits. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 121, 170–183. ( 10.1016/j.pbb.2013.12.017) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choi DC, Furay AR, Evanson NK, Ostrander MM, Ulrich-Lai YM, Herman JP. 2007. Bed nucleus of the stria terminalis subregions differentially regulate hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity: implications for the integration of limbic inputs. J. Neurosci. 27, 2025–2034. ( 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4301-06.2007) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Toufexis D. 2007. Region- and sex-specific modulation of anxiety behaviours in the rat. J. Neuroendocrinol. 19, 461–473. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2007.01552.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hines M, Davis FC, Coquelin A, Goy RW, Gorski RA. 1985. Sexually dimorphic regions in the medial preoptic area and the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis of the guinea pig brain: a description and an investigation of their relationship to gonadal steroids in adulthood. J. Neurosci. 5, 40–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guillamón A, Segovia S, del Abril A. 1988. Early effects of gonadal steroids on the neuron number in the medial posterior region and the lateral division of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis in the rat. Dev. Brain Res. 44, 281–290. ( 10.1016/0165-3806(88)90226-X) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allen LS, Gorski RA. 1990. Sex difference in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis of the human brain. J. Comp. Neurol. 302, 697–706. ( 10.1002/cne.903020402) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Forger NG, Rosen GJ, Waters EM, Jacob D, Simerly RB, de Vries GJ. 2004. Deletion of Bax eliminates sex differences in the mouse forebrain. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 13 666–13 671. ( 10.1073/pnas.0404644101) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chung WC, Swaab DF, De Vries GJ. 2000. Apoptosis during sexual differentiation of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis in the rat brain. J. Neurobiol. 43, 234–243. () [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gotsiridze T, Kang N, Jacob D, Forger NG. 2007. Development of sex differences in the principal nucleus of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis of mice: role of Bax-dependent cell death. Dev. Neurobiol. 67, 355–362. ( 10.1002/dneu.20353) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ahern TH, Krug S, Carr AV, Murray EK, Fitzpatrick E, Bengston L, McCutcheon J, De Vries GJ, Forger NG. 2013. Cell death atlas of the postnatal mouse ventral forebrain and hypothalamus: effects of age and sex. J. Comp. Neurol. 521, 2551–2569. ( 10.1002/cne.23298) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hisasue S, Seney ML, Immerman E, Forger NG. 2010. Control of cell number in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis of mice: role of testosterone metabolites and estrogen receptor subtypes. J. Sex. Med. 4, 1401–1409. ( 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01669.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cosgrove MS, Wolberger C. 2005. How does the histone code work? Biochem. Cell Biol. 83, 468–476. ( 10.1139/o05-137) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matsuda KI, Mori H, Nugent BM, Pfaff DW, McCarthy MM, Kawata M. 2011. Histone deacetylation during brain development is essential for permanent masculinization of sexual behavior. Endocrinology 152, 2760–2767. ( 10.1210/en.2011-0193) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nan X, Ng HH, Johnson CA, Laherty CD, Turner BM, Eisenman RN, Bird A. 1998. Transcriptional repression by the methyl-CpG-binding protein MeCP2 involves a histone deacetylase complex. Nature 393, 386–389. ( 10.1038/30764) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dantas Machado AC, Zhou T, Rao S, Goel P, Rastogi C, Lazarovici A, Bussemaker HJ, Rohs R. 2015. Evolving insights on how cytosine methylation affects protein-DNA binding. Brief Funct. Genomics 14, 61–73. ( 10.1093/bfgp/elu040) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kurian JR, Bychowski ME, Forbes-Lorman RM, Auger CJ, Auger AP. 2008. MeCP2 organizes juvenile social behavior in a sex-specific manner. J. Neurosci. 28, 7137–7142. ( 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1345-08.2008) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nugent BM, Wright CL, Shetty AC, Hodes GE, Lenz KM, Mahurkar A, Russo SJ, Devine SE, McCarthy MM. 2015. Brain feminization requires active repression of masculinization via DNA methylation. Nat. Neurosci. 18, 690–697. ( 10.1038/nn.3988) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gorski RA, Gordon JH, Shryne JE, Southam AM. 1978. Evidence for a morphological sex difference within the medial preoptic area of the rat brain. Brain Res. 148, 333–346. ( 10.1016/0006-8993(78)90723-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Amateau SK, McCarthy MM. 2002. A novel mechanism of dendritic spine plasticity involving estradiol induction of prostaglandin-E2. J. Neurosci. 22, 8586–8596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Amateau SK, McCarthy MM. 2002. Sexual differentiation of astrocyte morphology in the developing rat preoptic area. J. Neuroendocrinol. 14, 904–910. ( 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2002.00858.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lenz KM, Nugent BM, McCarthy MM. 2012. Sexual differentiation of the rodent brain: dogma and beyond. Front. Neurosci. 6, 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mosley M, Weathington J, Castillo-Ruiz A, Forger NG. 2015. Effects of DNA methyltransferase inhibition on sexually dimorphic cell groups in the preoptic area. Program No. 245.11. 2015 Neuroscience Meeting Planner. Washington, DC: Society for Neuroscience, 2015.

- 42.Gilmore RF, Varnum MM, Forger NG. 2012. Effects of blocking developmental cell death on sexually dimorphic calbindin cell groups in the preoptic area and bed nucleus of the stria terminalis. Biol. Sex Differ. 3, 5 ( 10.1186/2042-6410-3-5) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kelly DA, Varnum MM, Krentzel AA, Krug S, Forger NG. 2013. Differential control of sex differences in estrogen receptor α in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis and anteroventral periventricular nucleus. Endocrinol. 154, 3836–3846. ( 10.1210/en.2013-1239) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nusinzon I, Horvath CM. 2003. Interferon-stimulated transcription and innate antiviral immunity require deacetylase activity and histone deacetylase 1. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 14 742–14 747. ( 10.1073/pnas.2433987100) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Klampfer L, Huang J, Swaby LA, Augenlicht L. 2004. Requirement of histone deacetylase activity for signaling by STAT1. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 30 358–30 368. ( 10.1074/jbc.M401359200) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wilson MA, Ricci AR, Deroo BJ, Archer TK. 2002. The histone deacetylase inhibitor trichostatin A blocks progesterone receptor-mediated transactivation of the mouse mammary tumor virus promoter in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 15 171–15 181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weaver IC, Meaney MJ, Szyf M. 2006. Maternal care effects on the hippocampal transcriptome and anxiety-mediated behaviors in the offspring that are reversible in adulthood. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 3480–3485. ( 10.1073/pnas.0507526103) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Glaser KB, Staver MJ, Waring JF, Stender J, Ulrich RG, Davidsen SK. 2003. Gene expression profiling of multiple histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors: defining a common gene set produced by HDAC inhibition in T24 and MDA carcinoma cell lines. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2, 151–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Menegola E, Di Renzo F, Broccia ML, Giavini E. 2006. Inhibition of histone deacetylase as a new mechanism of teratogenesis. Birth Defects Res. C Embryo Today 78, 345–353. ( 10.1002/bdrc.20082) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ghahramani NM, et al. 2014. The effects of perinatal testosterone exposure on the DNA methylome of the mouse brain are late-emerging. Biol. Sex Differ. 5, 8 ( 10.1186/2042-6410-5-8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Spiers H, Hannon E, Schalkwyk LC, Smith R, Wong CC, O'Donovan MC, Bray NJ, Mill J. 2015. Methylomic trajectories across human fetal brain development. Genome Res. 25, 338–352. ( 10.1101/gr.180273.114) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shen EY, Ahern TH, Cheung I, Straubhaar J, Dincer A, Houston I, de Vries GJ, Akbarian S, Forger NG. 2015. Epigenetics and sex differences in the brain: A genome-wide comparison of histone-3 lysine-4 trimethylation (H3K4me3) in male and female mice. Exp. Neurol. 268, 21–29. ( 10.1016/j.expneurol.2014.08.006) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xu H, Wang F, Liu Y, Yu Y, Gelernter J, Zhang H. 2014. Sex-biased methylome and transcriptome in human prefrontal cortex. Hum. Mol. Genet. 23, 1260–1270. ( 10.1093/hmg/ddt516) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Siiteri PK, Wilson JD. 1974. Testosterone formation and metabolism during male sexual differentiation in the human embryo. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 38, 113–125. ( 10.1210/jcem-38-1-113) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Reyes FI, Boroditsky RS, Winter JSD, Faiman C. 1974. Studies on human sexual development. II. Fetal and maternal serum gonadotrophic and sex steroid concentrations. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 38, 612–617. ( 10.1210/jcem-38-4-612) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bernstein BE, Humphrey EL, Erlich RL, Schneider R, Bouman P, Liu JS, Kouzarides T, Schreiber SL. 2002. Methylation of histone H3 Lys 4 in coding regions of active genes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 8695–8700. ( 10.1073/pnas.082249499) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Santos-Rosa H, Schneider R, Bannister AJ, Sherriff J, Bernstein BE, Emre NC, Schreiber SL, Mellor J, Kouzarides T. 2002. Active genes are tri-methylated at K4 of histone H3. Nature 419, 407–411. ( 10.1038/nature01080) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Azuara V, et al. 2006. Chromatin signatures of pluripotent cell lines. Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 532–538. ( 10.1038/ncb1403) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Csankovszki G, Nagy A, Jaenisch R. 2001. Synergism of Xist RNA, DNA methylation, and histone hypoacetylation in maintaining X chromosome inactivation. J. Cell Biol. 153, 773–783. ( 10.1083/jcb.153.4.773) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yang F, et al. 2015. The lncRNA Firre anchors the inactive X chromosome to the nucleolus by binding CTCF and maintains H3K27me3 methylation. Genome Biol. 16, 52 ( 10.1186/s13059-015-0618-0) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wijchers PJ, Festenstein RJ. 2011. Epigenetic regulation of autosomal gene expression by sex chromosomes. Trends Genet. 27, 132–140. ( 10.1016/j.tig.2011.01.004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Arnold AP. 2012. The end of gonad-centric sex determination in mammals. Trends Genet. 28, 55–561. ( 10.1016/j.tig.2011.10.004) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.De Vries GJ. 2004. Minireview: sex differences in adult and developing brains: compensation, compensation, compensation. Endocrinology 145, 1063–1068. ( 10.1210/en.2003-1504) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Guo JU, et al. 2014. Distribution, recognition and regulation of non-CpG methylation in the adult mammalian brain. Nat. Neurosci. 17, 215–222. ( 10.1038/nn.3607) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Xie W, Barr CL, Kim A, Yue F, Lee AY, Eubanks J, Dempster EL, Ren B. 2012. Base-resolution analyses of sequence and parent-of-origin dependent DNA methylation in the mouse genome. Cell 148, 816–831. ( 10.1016/j.cell.2011.12.035) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lister R, et al. 2013. Global epigenomic reconfiguration during mammalian brain development. Science 341, 1237905 ( 10.1126/science.1237905) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schwarz JM, Nugent BM, McCarthy MM. 2010. Developmental and hormone-induced epigenetic changes to estrogen and progesterone receptor genes in brain are dynamic across the life span. Endocrinology 151, 4871–4881. ( 10.1210/en.2010-0142) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Morris MJ, Monteggia LM. 2014. Role of DNA methylation and the DNA methyltransferases in learning and memory. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 16, 359–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fortress AM, Frick KM. 2014. Epigenetic regulation of estrogen-dependent memory. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 35, 530–549. ( 10.1016/j.yfrne.2014.05.001) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Globisch D, Münzel M, Müller M, Michalakis S, Wagner M, Koch S, Brückl T, Biel M, Carell T. 2010. Tissue distribution of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine and search for active demethylation intermediates. PLoS ONE 5, e15367 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0015367) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Landan G, et al. 2012. Epigenetic polymorphism and the stochastic formation of differentially methylated regions in normal and cancerous tissues. Nat. Genet. 44, 1207–1214. ( 10.1038/ng.2442) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jeltsch A, Jurkowska RZ. 2014. New concepts in DNA methylation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 39, 310–318. ( 10.1016/j.tibs.2014.05.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Weaver IC, Cervoni N, Champagne FA, D'Alessio AC, Sharma S, Seckl JR, Dymov S, Szyf M, Meaney MJ. 2004. Epigenetic programming by maternal behavior. Nat. Neurosci. 7, 847–854. ( 10.1038/nn1276) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cheung I, Shulha HP, Jiang Y, Matevossian A, Wang J, Weng Z, Akbarian S. 2010. Developmental regulation and individual differences of neuronal H3K4me3 epigenomes in the prefrontal cortex. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 8824–8829. ( 10.1073/pnas.1001702107) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shulha HP, Cheung I, Guo Y, Akbarian S, Weng Z. 2013. Coordinated cell type-specific epigenetic remodeling in prefrontal cortex begins before birth and continues into early adulthood. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003433 ( 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003433) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Strahl BD, Allis CD. 2000. The language of covalent histone modifications. Nature 403, 41–45. ( 10.1038/47412) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Joel D. 2012. Genetic-gonadal-genitals sex (3G-sex) and the misconception of brain and gender, or, why 3G-males and 3G-females have intersex brain and intersex gender. Biol. Sex Differ. 3, 27 ( 10.1186/2042-6410-3-27) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lim SJ, Tan TW, Tong JC. 2010. Computational epigenetics: the new scientific paradigm. Bioinformation 4, 331–337. ( 10.6026/97320630004331) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]