Abstract

Recent research suggests that men find portraits of ovulatory women more attractive than photographs of the same women taken during the luteal phase. Only few studies have investigated whether the same is true for women. The ovulatory phase matters to men because women around ovulation are most likely to conceive, and might matter to women because fertile women might pose a reproductive threat. In an online study 160 women were shown face pairs, one of which was assimilated to the shape of a late follicular prototype and the other to a luteal prototype, and were asked to indicate which face they found more attractive. A further 60 women were tested in the laboratory using a similar procedure. In addition to choosing the more attractive face, these participants were asked which woman would be more likely to steal their own date. Because gonadal hormones influence competitive behaviour, we also examined whether oestradiol, testosterone and progesterone levels predict women's choices. The women found neither the late follicular nor the luteal version more attractive. However, naturally cycling women with higher oestradiol levels were more likely to choose the ovulatory woman as the one who would entice their date than women with lower oestradiol levels. These results imply a role of oestradiol when evaluating other women who are competing for reproduction.

Keywords: menstrual cycle, fertility cue, ovulation, face perception, intra-sexual competition, oestrogen

1. Background

Ovulation cues in humans are subtle but perceivable (for a review, see [1]). Women have been reported to dance and walk ([2], but see [3]), sound [4,5], smell [6,7] and look [8–11] more attractive during the fertile days of their menstrual cycle. Most of these studies looked exclusively at preferences of men [2,5–7,10–12] as men directly benefit from ovulation detection in women: the likelihood of reproducing is highest with a woman who is in her fertile cycle phase (cf. [7]). For women, the benefit of detecting other women's fertility is less clear. Some researchers negate any adaptive function for women being sensitive to ovulation cues in other women (e.g. [13]) while others have claimed that it is also beneficial for women to detect ovulation in other women, especially in the context of intra-sexual competition (cf. [14]). For example, ovulatory women may be more likely to engage in poaching behaviours and they might be more attractive to men, posing a potential threat to other (non-ovulating) women. Indeed, previous studies have shown that men find ovulatory faces more attractive [10,11].

Here we investigate whether women show a similar preference for ovulatory faces to men. Women were shown pairs of faces, one of which depicted an ovulatory face, the other a luteal face, and were asked to choose the more attractive woman. According to some authors ([8], see also [15]), facial signals of ovulation might be identical to what is typically seen as attractive in women's faces. If this were true we would expect that both women and men should find female faces showing ovulation cues more attractive. Alternatively, if detecting ovulation cues is beneficial when competing for men (cf. [14]), then women might react differently to ovulatory women (see [16]) but they might not necessarily find them more attractive. To address this second hypothesis, we additionally asked women to choose the woman that would be more likely to entice their own date away from them. We also collected information on intra-sexual competition and examined whether women's fertility detection is associated with oestradiol, progesterone or testosterone levels. These gonadal hormones have been suggested to play a key role for intra-sexual competition [17,18]. We hypothesized that individual differences in the capacity to detect cues to ovulation are explained by psychological and biological markers of intra-sexual competition (ICS [19], sex hormones). Specifically, we expected that women with higher oestradiol and/or testosterone levels and higher ICS scores would more often choose the ovulatory face, especially when asked to pick the face that is more likely to entice their own date away.

2. Material and methods

(a). Stimuli

The current study used the identical standardized stimuli to [11], differing only in shape between the luteal and late follicular phase. In short, we first created composites of portraits of 18 naturally cycling (NC) women who had been photographed both during the late follicular cycle phase (ovulatory prototype) and during the luteal phase (luteal prototype) using PsychoMorph computer graphics software [20] (figure 1a; see the electronic supplementary material, S1).

Figure 1.

(a) Follicular and luteal prototype. Composite of 18 women during ovulation (left) and during the luteal phase of their menstrual cycle (right). (b) Sample stimuli. Stimulus pair (left = ovulatory stimulus, 100% transforms). (Online version in colour.)

Twenty new frontal female portraits [21] were then shape-transformed in two steps (50% and 100%) towards the follicular and the luteal prototype ([20]; see the electronic supplementary material). Each transformed portrait was paired with its respective counterpart (figure 1b). The resulting 40 pairs (2 transformation steps × 20 face identities) were shown in both lateralizations on the screen, resulting in 80 trials.

(b). Online study

Data were collected online (www.unipark.de). Participants were recruited on social platforms (e.g. www.facebook.com, www.ronorp.net). Data of 160 women (146 heterosexual, 6 bisexual and 8 homosexual), aged between 18 and 40 years (M = 25.16, s.d. = 5.07), were included in the analyses.1 Of these, 77 used hormonal contraception (HC) and 82 reported no use of HC (NC) (1 non-disclosure). Participants gave informed consent to take part in the study by clicking the corresponding button. The face pair shown in fully randomized order and participants were asked to choose the more attractive face by point and click. Each face pair was shown until the participant's made a selection. After the experiment participants completed questionnaires assessing demographical data, HC use, cycle information and intra-sexual competition (ICS [19]).

(c). Laboratory study

Sixty female participants (59 heterosexual, 1 homosexual) aged between 18 and 31 years (M = 22.97, s.d. = 2.60) took part in this study. Thirty-one women reported use of HC and 29 participants reported NC. All women were tested once; NC women were tested during the luteal phase (6 to 8 days prior to expected menstruation, using the backward-counting method), and HC women were tested 6 to 8 days prior to pill break. They were naive regarding the purpose of the experiment and were fully debriefed at the end of the study. In the first block, participants were asked to choose the more attractive face (attractiveness task). In the following block, participants chose the face of the woman who would be more likely to entice their date away from them (date-enticement task).2 Order of blocks was held constant over all participants.

To reduce the impact of diurnal hormonal variation, all testing took place between noon and 19.00 h [22]. Participants were asked to refrain from eating, drinking anything other than water, and intense physical exercise for at least half an hour prior to the experiment. Upon arrival, participants provided a saliva sample using Salicaps (IBL International, Hamburg, Germany). An independent laboratory (Dresden Lab Service GmbH, Dresden, Germany) analysed testosterone, oestradiol (E2) and progesterone in the samples using luminescence immunoassay kits adopted for the analysis of salivary samples (IBL International, Hamburg, Germany).

3. Results

We analysed the percentage choice of ovulatory face. Because a paired t-test revealed no difference between the two transformation steps (all ps > 0.73), the data were pooled across transformation steps. Results showed that the ovulatory face was not chosen more often than expected by chance (0.50), t159 = −0.05, p = 0.961, d = −0.01 (online study) and t59 = 1.21, p = 0.231, d = 0.31 (laboratory study), reflecting that participants found neither the follicular nor the luteal face more attractive. They also did not suspect either version to be more likely to entice away their own date, t59 = 1.48, p = 0.143, d = 0.39. Choices did not differ between NC women and women taking HC (all ps > 0.41).

Simple regression analyses revealed that ICS (all βs < 0.07, ps > 0.387) did not predict which faces were chosen in either study or either task.

(a). Hormonal data

Independent t-tests revealed that NC women had significantly higher testosterone (t58 = 3.16, p < 0.01, d = 0.83), progesterone (t58 = 3.28, p < 0.01, d = 0.86) and oestradiol levels (t58 = 3.50, p < 0.001, d = 0.92) than HC women.

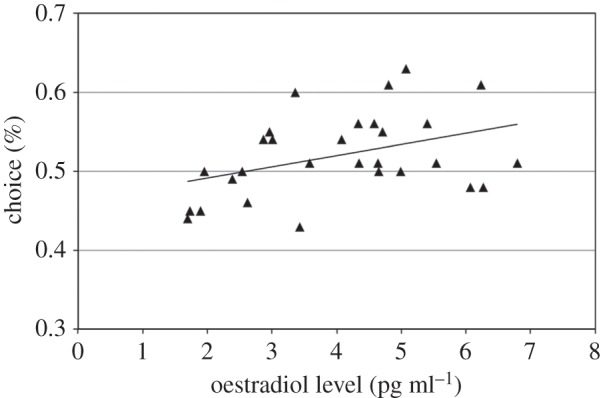

Multiple stepwise regression analyses with all three hormones were run for NC women, separately for each task. Only NC women were included because HC women have artificially altered levels of gonadal hormones and it is unlikely that hormones in HC women will carry equivalent information to those occurring in NC women. In the date-enticement task, the best fit was found by including only oestradiol levels (R2 = 0.22, F = 7.54, p = 0.011; β = 0.47; figure 2). Table 1 depicts coefficients and significance values of all three predictors in the full model. When only considering women with high oestradiol levels (median split), we found that women were more likely to choose the ovulatory face as the one who would entice away their date (t14 = 3.08, p = 0.008, d = 1.65). No hormone predicted the choices in the attractiveness task (all ps > 0.187; table 1).

Figure 2.

Association between oestradiol level and percentage choice of ovulatory face in the date-enticement task for NC women.

Table 1.

Multiple regression analysis of the attractiveness and date-enticement tasks. Note: hormone values are log-transformed. Raw β-values are depicted.

| attractiveness task |

date-enticement task |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| predictor | β | t | p-value | β | t | p-value |

| oestradiol | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.928 | 0.15 | 2.35 | 0.027 |

| testosterone | 0.06 | 1.35 | 0.188 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.998 |

| progesterone | 0.02 | 0.56 | 0.580 | −0.01 | −0.08 | 0.663 |

4. Discussion

We found that women do not find faces of ovulatory women particularly attractive, but that NC women with high oestradiol levels were more likely to choose the ovulatory face when asked which woman would be more likely to entice the participant's own date away from her.

Recent studies using the same [11] or similar stimuli [10] have shown that men find the ovulatory face more attractive. Such results can be interpreted as men's ability to detect ‘leaky cues’ to ovulation, serving men in the arms race between women's effort to conceal ovulation and men's selective advantage to detect it. Alternatively, men's preference for ovulatory cues might occur because facial signals of ovulation are identical to what is typically seen as attractive in women's faces [8,15]. In this case, women (like men) should find ovulatory faces more attractive than luteal faces, which was not the case in this study.

While ovulation-linked cues do not render a woman's face more attractive for other women, we show that women are not completely blind to these cues. We found that oestradiol levels in NC women predicted how well they were able to discriminate ovulatory from luteal faces in a setting implying intra-sexual competition (date-enticement). This is in line with studies finding positive associations between oestradiol levels and competitive behaviour among women, such as greater emotional reaction to sexual infidelity [23], or objectification of other women [24]. Our data suggest that in women oestrogen is more related to intra-sexual competition than testosterone. On the other hand, women with higher trait oestradiol levels are generally thought to be more fertile. A more functionalist explanation for women with higher oestradiol levels being more attuned to the ovulatory status of other women might therefore be that ovulatory women (who are currently fertile) pose a greater threat to women with high oestradiol levels (who are currently not fertile but have a high potential fertility).

We note that we employed a between-participant design, testing all women during the luteal cycle phase. Our aim was to investigate whether women's ability to differentiate between ovulatory and luteal faces can be linked to inter-individual differences in hormone levels. By showing that luteal oestradiol levels (as they occur on an inter-individual level) predict how often women choose the ovulatory face as the one that would be more likely to entice away her own date, we extend previous findings that have discussed intra-sexual competition in the context of oestradiol levels. It will be an interesting next step to relate the findings of the present study to conception probability by investigating intra-individual changes over the cycle (e.g. high conception probability versus low conception probability).

One limitation of this study is the relatively small sample size in the laboratory study. The association between oestradiol and the ability to discriminate between ovulatory and luteal women needs to be replicated in the future studies before it can be fully relied on.

In conclusion, we found a positive association in NC women between oestradiol levels and the ability to discriminate between ovulatory and luteal women's faces in the absence of any indication that women find ovulatory faces more attractive. Detecting subtle cues of current fertility in other women may serve to enhance women's engagement in specific mate guarding and/or competitive strategies.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Asha-Naima Ferrante and Livio Leu for their help with data collection.

Endnotes

Participants who assessed the survey via smartphone or tablet were excluded (N=31), because picture resolution was considered too low for the purpose of this study.

The exact instructions for this task were: ‘For this task, imagine that you have got a date with a man you really fancy. Please decide which of the two depicted women would be more likely to entice your date away from you’.

Ethics

Research on human participants was carried out with ethical approval from the Faculty of Human Sciences of the University of Bern (Project Number 2012–8-167070) and participant consent was obtained.

Data accessibility

All data are available as the electronic supplementary material (Data_Online Study_biolletters/Data_Laboratory Study_biolletters).

Authors' contributions

J.S.L., C.B. and F.P. designed the study, participated in stimulus creation and data analysis, and wrote the manuscript. All authors gave final approval for publication of the final version of the manuscript and agree to be held accountable for the content therein.

Competing interests

We have no competing interests.

Funding

This study was supported by a grant from the Swiss National Science Foundation awarded to J.L. (grant no. PP00P1_139072).

References

- 1.Haselton MG, Gildersleeve K. 2011. Can men detect ovulation? Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 20, 87–92. ( 10.1177/0963721411402668) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fink B, Hugill N, Lange BP. 2012. Women's body movements are a potential cue to ovulation. Pers. Individual Differ. 53, 759–763. ( 10.1016/j.paid.2012.06.005) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Provost MP, Quinsey VL, Troje NF. 2008. Differences in gait across the menstrual cycle and their attractiveness to men. Arch. Sex Behav. 37, 598–604. ( 10.1007/s10508-007-9219-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pipitone RN, Gallup GG. 2008. Women's voice attractiveness varies across the menstrual cycle. Evol. Hum. Behav. 29, 268–274. ( 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2008.02.001) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fischer J, Semple S, Fickenscher G, Jurgens R, Kruse E, Heistermann M, Amir O. 2011. Do women's voices provide cues of the likelihood of ovulation? The importance of sampling regime. PLoS ONE 6, 8 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0024490) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gildersleeve KA, Haselton MG, Larson CM, Pillsworth EG. 2012. Body odor attractiveness as a cue of impending ovulation in women: evidence from a study using hormone-confirmed ovulation. Horm. Behav. 61, 157–166. ( 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2011.11.005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Havlicek J, Dvorakova R, Bartos L, Flegr J. 2006. Non-advertized does not mean concealed: body odour changes across the human menstrual cycle. Ethology 112, 81–90. ( 10.1111/j.1439-0310.2006.01125.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oberzaucher E, Katina S, Schmehl S, Holzleitner I, Mehu-Blantar I, Grammer K. 2012. The myth of hidden ovulation: shape and texture changes in the face during the menstrual cycle. J. Evol. Psychol. 10, 163–175. ( 10.1556/JEP.10.2012.4.1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roberts SC, Havlicek J, Flegr J, Hruskova M, Little AC, Jones BC, Perrett DI, Petrie M. 2004. Female facial attractiveness increases during the fertile phase of the menstrual cycle. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 271, S270–S272. ( 10.1098/rsbl.2004.0174) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bobst C, Lobmaier JS. 2012. Men's preference for the ovulating female is triggered by subtle face shape differences. Horm. Behav. 62, 413–417. ( 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2012.07.008) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bobst C, Lobmaier JS. 2014. Is preference for ovulatory female's faces associated with men's testosterone levels? Horm. Behav. 66, 487–492. ( 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2014.06.015) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh D, Bronstad PM. 2001. Female body odour is a potential cue to ovulation. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 268, 797–801. ( 10.1098/rspb.2001.1589) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuukasjarvi S, Eriksson CJP, Koskela E, Mappes T, Nissinen K, Rantala MJ. 2004. Attractiveness of women's body odors over the menstrual cycle: the role of oral contraceptives and receiver sex. Behav. Ecol. 15, 579–584. ( 10.1093/beheco/arh050) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosvall KA. 2011. Intrasexual competition in females: evidence for sexual selection? Behav. Ecol. 22, 1131–1140. ( 10.1093/beheco/arr106) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Havliček J, Cobey KD, Barrett L, Klapilová K, Roberts SC. 2015. The spandrels of Santa Barbara? A new perspective on the peri-ovulation paradigm. Behav. Ecol. 26, 1249–1260. ( 10.1093/beheco/arv064) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maner JK, McNulty JK. 2013. Attunement to the fertility status of same-sex rivals: women's testosterone responses to olfactory ovulation cues. Evol. Hum. Behav. 34, 412–418. ( 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2013.07.005) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fisher ML. 2004. Female intrasexual competition decreases female facial attractiveness. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 271, S283–S285. ( 10.1098/rsbl.2004.0160) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Archer J. 2006. Testosterone and human aggression: an evaluation of the challenge hypothesis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 30, 319–345. ( 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.12.007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buunk A, Fisher M. 2009. Individual differences in intrasexual competition. J. Evol. Psychol. 7, 37–48. ( 10.1556/JEP.7.2009.1.5) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tiddeman B, Burt M, Perrett D. 2001. Prototyping and transforming facial textures for perception research. IEEE Comput. Graph Appl. 21, 42–50. ( 10.1109/38.946630) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Minear M, Park DC. 2004. A lifespan database of adult facial stimuli. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 36, 630–633. ( 10.3758/bf03206543) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dickerson SS, Kemeny ME. 2004. Acute stressors and cortisol responses: a theoretical integration and synthesis of laboratory research. Psychol. Bull. 130, 355–391. ( 10.1037/0033-2909.130.3.355) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Geary DC, DeSoto MC, Hoard MK, Sheldon MS, Cooper ML. 2001. Estrogens and relationship jealousy. Hum. Nat. 12, 299–320. ( 10.1007/s12110-001-1001-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Piccoli V, Cobey KD, Carnaghi A. 2014. Hormonal contraceptive use and the objectification of women and men. Pers. Individ. Differ. 66, 44–47. ( 10.1016/j.paid.2014.03.004) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are available as the electronic supplementary material (Data_Online Study_biolletters/Data_Laboratory Study_biolletters).