Abstract

Whole genome sequencing of families of Arabidopsis has recently lent strong support to the heterozygote instability (HI) hypothesis that heterozygosity locally increases mutation rate. However, there is an important theoretical difference between the impact on base substitutions, where mutation rate increases in regions surrounding a heterozygous site, and the impact of HI on sequences such as microsatellites, where mutations are likely to occur at the heterozygous site itself. At microsatellite loci, HI should create a positive feedback loop, with heterozygosity and mutation rate mutually increasing each other. Direct support for HI acting on microsatellites is limited and contradictory. I therefore analysed AC microsatellites in 1163 genome sequences from the 1000 genomes project. I used the presence of rare alleles, which are likely to be very recent in origin, as a surrogate measure of mutation rate. I show that rare alleles are more likely to occur at locus-population combinations with higher heterozygosity even when all populations carry exactly the same number of alleles.

Keywords: microsatellite, heterozygosity, mutation rate, heterozygote instability, human, tandem repeat

1. Introduction

Much of classical population genetic theory is based on the largely untested assumption that alleles mutate independently. This assumption is challenged by the heterozygote instability (HI) hypothesis that heterozygous sites show increased mutability due to an extra round of DNA replication when they are recognized and ‘repaired’ in heteroduplex DNA formed during synapsis [1]. HI implies a link through heterozygosity between population size and mutation rate. Evidence for HI comes from the way SNPs are clustered [2] and a correlation between substitution rate and the amount of diversity lost as humans migrated out of Africa [3]. More recently, whole genome sequencing of Arabidopsis parents and offspring [4] has shown directly that HI operates in plants.

HI increases the substitution rate near heterozygous sites [4]. By contrast, at tandem repeat sequences, HI potentially increases the mutation rate of the heterozygous site itself, thereby creating a positive feedback loop. Indirect evidence for HI influencing microsatellite mutations comes from a correlation between human population size and evolutionary rate [5]. Direct mutation counting in pedigrees gives conflicting results, two small studies lending support [6,7] but a third, much larger study, finding no evidence [8]. However, all three mutation-counting studies focus on length differences between parental alleles rather than the key comparison between heterozygotes and homozygotes.

Direct counting of de novo microsatellite mutations in pedigrees requires prodigious experimental effort and the results are biased towards a small subset of loci with unusually high mutation rates [8,9]. To increase sample sizes and to extend the range of loci analysed, I exploited the fact that most new mutations are lost within a few generations of origin [10], implying that a large majority of rare alleles will be descended from recent mutations. Rare alleles may therefore offer a surrogate measure of mutation rate.

2. Material and methods

(a). Simulations

To test the assumption that most rare alleles are recent, I conducted stochastic simulations coded in C++. Diploid, randomly mating, constant-sized populations were created carrying two unlinked loci: L1, the mutating locus, initialized with allele 0, and L2, a reporter locus for the impact of neutral drift, initialized with two non-mutating alleles at equal frequency. At every generation a single, randomly chosen allele at L1 was mutated to an allele named as the current generation number and the two allele frequencies at L2 stored. Population size, N, was 10x, x chosen at random from a uniform distribution between three and five, giving a range of N between 1000 and 100 000. Alleles present at fewer than five copies in a sample of 1000 individuals are deemed rare. Every 100 generations, 1000 individuals were sampled and L1 assayed for rare alleles. Mutant age was calculated as current generation number minus the rare allele number. Drift since mutation origin was measured as the absolute change in allele frequency seen at L2. Simulations were run for N generations to establish a large number of drifting mutations, then sampled for a maximum of N further generations, being terminated if L2 drifted to fixation; 1000 replicates were run with no more than 100 rare allele sampled from each run.

(b). Data

Sequence data for 1163 individuals were downloaded from the 1000 genomes website (ftp://ftp.1000genomes.ebi.ac.uk/vol1/ftp/) [11] as fastq.gz files if they were from sequencing centres SC, BI, BGI or BCM, were 100 bp paired-end reads generated by HiSeq 2000 machines and derived from any of 18 populations comprising people living in the region attributed to them, two exceptions being UK Sri Lankans and Telugu (see electronic supplementary material, ESM1). Populations were combined into four regional groups: Africa (LWK, ESN, YRI, MSL, GWD, total N = 355), Europe (FIN, GBR, IBS, TSI, total N = 233), Central Southern Asia (ITU, STU, BEB, PJL, total N = 298) and East Asia (CHB, CHS, CDX, KHV, JPT, total N = 223).

I focused on the most abundant dinucleotide motif (AC) and obtained repeat numbers using the likelihood-based program lobSTR v. 3.0.3 [12]. Other motifs are either too rare (e.g. tetranucleotides) or appear problematic (lobSTR finds half the expected number of AT motifs). Multiple fastq files for each individual were combined and analysed on the Cambridge High Performance Computing facility, using lobSTR's default parameter values. Individual .gz files were combined and analysed without unzipping using a custom script written by Jenny Barna. As lobSTR returns both pure and interrupted repeat tracts, for a view on mutations specifically affecting pure AC repeats, the resulting output VCF files were processed using custom C++ scripts (electronic supplementary material, ESM2). Each allele sequence was scanned and the longest pure AC tract returned. To avoid bias associated with variable coverage between individuals, only one allele was stored per individual, chosen at random where two were present.

3. Results

(a). Drift and new mutations

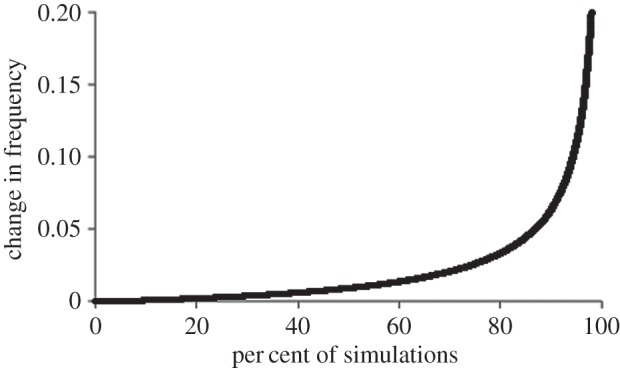

Across a wide range of population sizes, 95% of rare alleles represent mutations that occurred over a timescale in which other alleles changed in frequency by less than 10% and 50% of rare alleles occurred over a timescale where frequencies change by less than 1% (figure 1). This confirms that rare alleles provide a reasonable surrogate measure of mutation rate in relation to current heterozygosity. Little or no dependence on population size was observed, reflecting the fact that drift influences the rate of both the rise in frequency of rare alleles and the change in frequency of the common alleles: in large populations both processes progress more slowly.

Figure 1.

Relationship between rare alleles and drift. Stochastic simulations were conducted of a single homogeneous population in which individuals mate randomly and carry two loci. One locus experiences a single unique mutation at each generation. The other locus does not mutate but evolves purely through drift. The simulated data are scanned for rare alleles, defined as alleles present in fewer than five copies in a sample of 1000 individuals. The graph depicts the cumulative distribution of rare alleles, quantified in terms of the amount of drift that has occurred since the progenitor mutation, and expressed as the change in frequency of alleles at the drifting locus (y-axis). A large majority of rare alleles represent mutations that occurred over a timescale during which the drifting locus alleles change in frequency by only 1 or 2%.

(b). Does heterozygosity increase the chance of a mutation occurring?

Data were returned for 154 858 AC microsatellites. From these, I extracted all 6521 instances of loci with: (a) greater than 500 lobSTR allele calls across all samples; (b) one putative new mutation (PNM), defined as an allele present in fewer than five copies and restricted to one of the four population groups; (c) where, excluding the PNM, all population groups carry exactly the same number and identity of alleles. Requirement (c) ensures that variation in expected heterozygosity ( fi is the frequency of the ith allele, individuals carrying the PNM are excluded) between groups was due entirely to stochastic variation in the evenness of the allele frequencies. Having one PNM plus two other alleles sets the minimum number of alleles at a locus to three. An upper limit of 10 alleles was set because above this number fewer than 10 loci qualify and allele-calling becomes less reliable. To test the HI hypothesis, I calculated the difference in He between the group with the PNM and the average on the other three groups. The mean difference is small, 0.056, but highly significantly greater in populations with a PNM (one sample t-test, t6520 = 7.47, p = 9 × 10−14). This difference is not due to a subtle difference in mean length (mean difference in length = 0.0008 repeats, t6520 = 0.37, n.s.).

fi is the frequency of the ith allele, individuals carrying the PNM are excluded) between groups was due entirely to stochastic variation in the evenness of the allele frequencies. Having one PNM plus two other alleles sets the minimum number of alleles at a locus to three. An upper limit of 10 alleles was set because above this number fewer than 10 loci qualify and allele-calling becomes less reliable. To test the HI hypothesis, I calculated the difference in He between the group with the PNM and the average on the other three groups. The mean difference is small, 0.056, but highly significantly greater in populations with a PNM (one sample t-test, t6520 = 7.47, p = 9 × 10−14). This difference is not due to a subtle difference in mean length (mean difference in length = 0.0008 repeats, t6520 = 0.37, n.s.).

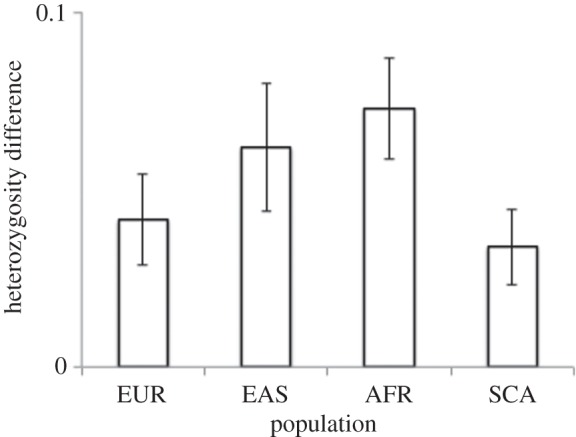

A link between heterozygosity and apparent mutation rate could potentially arise spuriously through allele-calling errors. Population substructure and demographic history can both drive variation in heterozygosity between populations, even when all populations carry the same number of alleles. For example, in the current dataset heterozygosity is on average 18% higher in Africa than elsewhere even when allele number does not vary between populations. Spurious patterns could therefore arise if some PNMs are actually mis-called alleles in a population group with higher heterozygosity. To address this issue, I repeated the analysis after transforming the data such that heterozygosity within each population group had mean = 0 and unit standard deviation. Population-locus combinations with PNMs still show a highly significant excess heterozygosity compared the same loci in other population groups (figure 2, data partitioned by population group, all groups show individually significant excess: Europe, excess = 0.041, t1347 = 3.21, p = 0.001; East Asia, excess = 0.062, t946 = 3.4, p = 0.0007; Africa, excess = 0.073, t2696 = 5.1, p = 4 × 10−7; Central Southern Asia, excess = 0.034, t1643 = 2.81, p = 0.0015). For more details, see electronic supplementary material, ESM3. For comparison, the analysis was repeated for AG and AT (electronic supplementary material, ESM4a and 4b), and after filtering to remove allele calls with quality scores below 0.9 (electronic supplementary material 4c), all yielding similar results.

Figure 2.

Difference in heterozygosity between population groups with and without rare alleles, partitioned by population group. Rare alleles are defined as alleles present at fewer than five copies and restricted to one population group. At each locus, excluding the rare allele itself, all populations carry the same number and identity of alleles. Data were transformed such that mean heterozygosity within each population group was zero with unit standard deviation. The vertical axis is difference in heterozygosity between the population group with a rare allele and the average heterozygosity among the remaining three population groups. Population groups are Europe (EUR, N = 1348 loci), East Asia (EAS, N = 947 loci), Africa (AFR, N = 2697 loci) and Central Southern Asia (CSA, N = 1529 loci). Bars denote means±1 s.e. of the mean. All data points are significantly positive. Total sample size = 6521 loci. For AT and AG repeats, see the electronic supplementary material, ESM4a.

4. Discussion

Previous tests of the HI hypothesis in microsatellites have either been indirect [5] or focused on length differences between parental alleles [6–8]. The latter effect is probably absent, though a robust test needs to allow for the greater visibility of mutations from homozygote parents, a tendency that is enhanced by the tendency for long alleles to contract and short alleles to expand [8,13]. Mutations from pedigrees also often derived mainly from a small subset of possibly unusual loci. Use of rare alleles as surrogate indicators of recent mutations has yielded a large dataset from many low to medium variability loci that contribute negligibly to direct counting studies.

Even when all four population groups carry the same number of alleles, PNMs preferentially occur in the group with highest heterozygosity. By implication, heterozygous genotypes are more mutable. Alternative explanations are difficult to conceive. One possibility is that population groups vary in both the frequency of PNMs and heterozygosity, due variously to factors such as variation in sample quality, demographic history and sampling regime. If so, a correlation between heterozygosity and PNMs could arise by chance. However, such correlations should disappear if the data are transformed such that all groups have the same mean heterozygosity. That the correlations persist therefore precludes allele mis-calling as a plausible explanation. A further possibility is that selective sweeps both reduce heterozygosity and remove PNMs. However, selective sweeps appear rare in humans [14]. Moreover, sweeps would tend to create clusters of PNMs yet closer PNMs are not more likely to be in the same population group (logistic regression: response variable is adjacent PNMs in the same (=1) or different (=0) population group; predictor variable is distance between adjacent PNMs, t6495 = 0.28, p = 0.78). Finally, the reported trend might be driven by differences in mean repeat number between populations. This is excluded both by the stringent requirement for all populations to carry exactly the same alleles, and also by a direct test that reveals no significant length differences.

My results support further the idea that mutation rate is higher at/near heterozygous sites, undermining the classical assumption of independence between population size and mutation rate. Thus, as a population expands the resulting increase in heterozygosity will drive a further increase in microsatellite mutation rate. The emerging picture is one where HI impacts both mutation rate in regions flanking heterozygous sites [3,4] and also has a direct impact on tandem repeats [1]. The feedback loop so-created has important and interesting implications for population genetics in terms of the way diversity is generated and used as a measure of population divergence. Raw data files are available as electronic supplementary material, ESM5a, 5b and 5c.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Data accessibility

The raw data generated by my analyses are available in the electronic supplementary material.

Competing interests

I declare I have no competing interests.

Funding

I received no funding for this study.

References

- 1.Amos W. 2010. Heterozygosity and mutation rate: evidence for an interaction and its implications. BioEssays 32, 82–90. ( 10.1002/bies.200900108) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amos W. 2010. Even small SNP clusters are non-randomly distributed: is this evidence of mutational non-independence? Proc. R. Soc. B 277, 1443–1449. ( 10.1098/rspb.2009.1757) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amos W. 2013. Variation in heterozygosity predicts variation in human substitution rates between populations, individuals and genomic regions. PLoS ONE 8, e63048 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0063048) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang S, Wang L, Huang J, Zhang X, Yuan Y, Chen J-Q, Hurst LD, Tian D. 2015. Parent-progeny sequencing indicates higher mutation rates in heterozygotes. Nature 523, 463–467. ( 10.1038/nature14649) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amos W. 2011. Population-specific links between heterozygosity and the rate of human microsatellite evolution. J. Mol. Evol. 72, 215–221. ( 10.1007/s00239-010-9423-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amos W, Sawcer SJ, Feakes R, Rubinsztein DC. 1996. Microsatellites show mutational bias and heterozygote instability. Nat. Genet. 13, 390–391. ( 10.1038/ng0896-390) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Masters BS, Johnson LS, Johnson BGP, Brubaker JL, Sakaluk SK, Thompson CF. 2011. Evidence for heterozygote instability in microsatellite loci in house wrens. Biol. Lett. 7, 127–130. ( 10.1098/rsbl.2010.0643) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun JX, et al. 2012. A direct characterization of human mutation based on microsatellites. Nat. Genet. 44, 1161–1165. ( 10.1038/ng.2398) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ellegren H. 2000. Microsatellite mutations in the germline: implications for evolutionary inference. Trends Genet. 16, 551–558. ( 10.1016/S0168-9525(00)02139-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crow JF, Kimura M. 1970. An introducton to population genetic theory. New York, NY: Harper and Row. [Google Scholar]

- 11.The 1000 Genomes Project Consortium. 2012. An integrated map of genetic variation from 1,092 human genomes. Nature 491, 56–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gymrek M, Golan D, Rosset S, Erlich Y. 2012. lobSTR: a short tandem repeat profiler for personal genomes. Genome Res. 22, 1154–1162. ( 10.1101/gr.135780.111) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang Q-Y, Xu F-H, Shen H, Deng H-Y, Liu Y-J, Liu Y-Z, Li J-L, Recker RR, Deng H-W. 2002. Mutation patterns at dinucleotide microsatellite loci in humans. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 70, 625–634. ( 10.1086/338997) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wollstein A, Stephan W. 2015. Inferring positive selection in humans from genomic data. Invest. Genet. 6, 5 ( 10.1186/s13323-015-0023-1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw data generated by my analyses are available in the electronic supplementary material.