Abstract

Purpose

Multiple studies have demonstrated that in healthy subjects painful stimuli applied to one part of the body inhibit pain sensation in other parts of the body, a phenomenon referred to as conditioned pain modulation (CPM). CPM is related to the presence of endogenous pain control systems. Studies have demonstrated deficits in CPM-associated inhibition in many, but not all chronic pain disorders. The present study sought to determine whether CPM was altered in subjects with Interstitial Cystitis/Bladder Pain Syndrome (IC/BPS).

Methods and Materials

Female subjects with and without the diagnosis of IC/BPS were studied psychophysically using quantitative cutaneous thermal, forearm ischemia and ice water immersion tests. CPM was assessed by quantifying the effects of immersion of the hand in ice water (conditioning stimulus) on threshold and tolerance of cutaneous heat pain (test stimulus) applied to the contralateral lower extremity.

Results

CPM responses of the subjects with IC/BPS were statistically different from those of healthy control subjects for both cutaneous thermal threshold and tolerance measures. Healthy control subjects demonstrated statistically significant increases in their thermal pain tolerances whereas subjects with the diagnosis of IC/BPS demonstrated statistically significant reductions in their thermal pain tolerances.

Conclusions

An endogenous pain inhibitory system normally observed with CPM was altered in subjects with IC/BPS. This identifies IC/BPS as similar to several other chronic pain disorders such as fibromyalgia and irritable bowel syndrome and suggests that a deficit in endogenous pain inhibitory systems may be a contributor to such chronic pain disorders.

Keywords: DNIC, Counterirritation, Bladder, Pain

INTRODUCTION

Multiple studies have demonstrated that in healthy subjects painful stimuli applied to one part of the body inhibit pain sensation in other parts of the body, a phenomenon referred to as conditioned pain modulation (CPM)1. We have previously demonstrated that reduced CPM is associated with an increase in clinical pain in a community-based sample2. Others have demonstrated that painful disorders such as fibromyalgia and irritable bowel syndrome3–7 are associated with deficits in endogenous pain inhibitory systems which is reflected as an alteration in CPM. Alterations in CPM have also been identified prospectively as predictors of difficult-to-control postoperative pain and with the development of chronic pain8–10. It is not known whether alterations in CPM are present in painful urological disorders such as interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome [IC/BPS]11.

We previously demonstrated that IC/BPS subjects are hypersensitive to both bladder and other deep tissue sensations12. It is therefore notable that most chronic pain disorders that have demonstrated alterations in CPM (e.g., chronic joint pain, fibromyalgia, headache, temporomandibular disorder, irritable bowel syndrome) have also displayed enhanced pain sensitivity on psychophysical testinge.g.5,6. However, other chronic pain disorders such as classical trigeminal neuralgia13, vulvodynia14,15 and rheumatoid arthritis16, which also have clear evidence of local hypersensitivity, have apparently normal CPM mechanisms. This suggests that alterations in CPM may reflect some underlying difference in central nervous system function that is associated with the development or maintenance of particular pathological processes. Since it is not known whether subjects with IC/BPS have alterations in CPM, the present studies sought to quantitatively compare the effects of a heterosegmental conditioning noxious stimulus (immersion of hand in ice water) on responses evoked by a noxious hot thermal test stimulus applied to the lower extremity in subjects with the diagnosis of IC/BPS with responses of healthy control subjects.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Study Summary

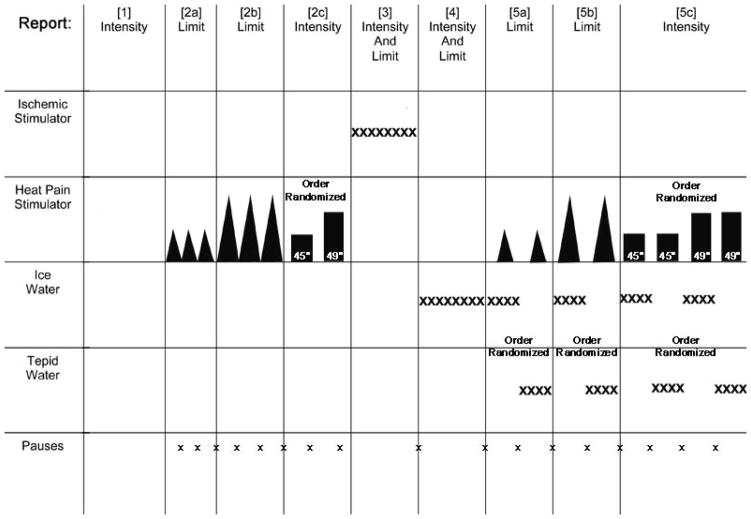

These studies were approved by the University of Alabama at Birmingham’s Institutional Review Board for Human Studies. 29 female subjects (15 subjects meeting both AUA11 and more stringent NIDDK consensus panel criteria for IC17 and 14 age-matched, healthy controls) were recruited and underwent a single session of testing summarized in Figure 1. Sequential measures consisted of [1] an initial voiding of urine with a rating related to discomfort; [2] measurement of thermal sensation in the right lower extremity, [3] measurement of tolerance of forearm muscle ischemia evoked by the tourniquet test; [4] testing of noxious intensity evoked by immersion of a hand in ice water; and then [5] repeat measure of thermal sensation to a test thermal stimulus (as in [2]) following either immersion of the left hand in ice water (the conditioning stimulus) or in room temperature (22°C) water (control stimulus) in counterbalanced order. The initial measure of thermal sensations (step [2] above) and ice water immersion [step 4 above] served as a “training sessions” for individuals so that novelty of those stimuli would be minimized, thereby limiting variability.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram summarizing the testing protocol. Different segments were performed in the following sequential order with some randomization of order within segments indicated. Segments included the following measures: [1] Void Report, [2a] Heat Threshold, [2b] Heat Tolerance, [2c] Heat Intensity, [3] Ischemic Tolerance, [4] Ice Water Tolerance, [5a] CPM of Heat Threshold, [5b] CPM of Heat Tolerance and [5c] CPM of Heat Intensity. See text for more complete description. Pauses of 2–5 minutes between stimuli presentation allowed recovery of sensations to baseline.

Void Report

Subjects were asked whether their voiding episode was painful and if it was, were asked to indicate how intense their pain was by giving a numerical value between 0 and 10 with 0=NO PAIN and 10= WORST PAIN EVER.

Hot Thermal Stimulus

The site of thermal testing was the lower extremity immediately proximal to the right ankle. Thermal pain sensitivity was assessed using a commercially available thermal stimulator (Medoc TSA-2001) used widely in clinical settings. This device delivers thermal stimuli to a 9 cm2 area of skin using a Peltier device and is controlled by a computer. Two types of thermal stimuli were delivered: 1) a slowly increasing thermal stimulus that the subject terminated by pressing a button when it first became painful (heat pain threshold) and on separate trials when it became as hot as they were willing to tolerate (heat pain tolerance), and 2) single, brief (2 s duration), noxious heat pulses (target temperature 45°C or 49°C) presented on two separate trials (order and precise site randomized) spaced three minutes apart. Subjects verbally rated each thermal pulse using a 0–100 numeric rating scale. Anchors on this scale were as follows: 0=no sensation, 20=barely painful, 100=most painful possible. This scale has shown good psychometric properties across multiple groups2,12. The pulses were terminated early if requested by the subject and assigned a score of 100.

Ischemic Stimulus

Ischemic pain was induced by occluding the arm with a standard blood pressure cuff for a limited time and having subjects perform 20 handgrip exercises at 50% of their predetermined strength maximum at 2-second intervals. Subjects gave pain ratings using a 0–100 pain scale and notified the experimenter when they wished to discontinue the procedure, the ischemic tolerance measure, with a pre-determined cutoff of 15-minutes.

(Ice) Water Immersion

This procedure consisted of inserting the left hand into a water bath maintained at 0–5°C (ice/water mixture) or 22°C (room temperature water). Subjects were instructed to keep their hand in the water as long as possible. On the first trial only ice water presented and the time in seconds to reach their maximal toleration of cold was recorded as their cold pain tolerance measure. Subjects rated their pain at 10 s intervals using a 0–100 scale with a two minute cutoff.

Conditioned Pain Modulation (CPM)

Subsequently, the water immersion was used as a conditioning stimulus prior to thermal test-stimulus testing. In those trials the hand was immersed in one of the two water baths for a maximum of 70 s (participants were asked to keep the hand immersed throughout this entire time period, but allowed to remove it early if necessary). Immediately after hand immersion, thermal testing of either the slowly rising stimulus (thermal threshold/tolerance measure) or the thermal pulses (thermal intensity measure) was initiated. The hand was dried after removing from the water and after 2 minutes an additional thermal test measure performed until all eight conditions (two temperatures of water x two modalities of testing x two intensities of thermal stimulus) of thermal testing had been performed. One HC and one IC subject removed their hands from the ice water immediately prior to determination of the heat pain tolerance measure; they indicated they were still experiencing cold pain when the test measure was obtained.

Statistics

All values represent means ± SEM unless otherwise stated. Statistical comparisons were performed with repeated measures ANOVA (with Tukeys HSD as post hoc method) or Student’s t-tests where appropriate.

RESULTS

Demographics

Subjects were 22–56 years old, 22 were Caucasians (13 IC, 9 HC). 6 were African-American (2 IC, 4 HC) and one of Asian descent (HC). 86% of IC subjects were on chronic daily analgesics (10 of 15 on chronic daily opioids); one HC commonly took ibuprofen. Co-morbidities were not formally investigated as part of this study, but self reports by subjects in a screening health survey indicated that four of the HC had regular headaches (1–2/mo) and two HC had intermittent back pain. In contrast, most of the IC subjects listed other pain problems with diagnoses of fibromyalgia (3), regular headaches (7), stomach pains (4) and regular back pain (9; often associated with bladder pain.) One of the IC subjects was not included in subsequent analysis (but is described below) because she had undergone a urinary diversion surgery (no other IC subjects had undergone similar surgery), but continued to have bladder pain.

Baseline Pain Measures

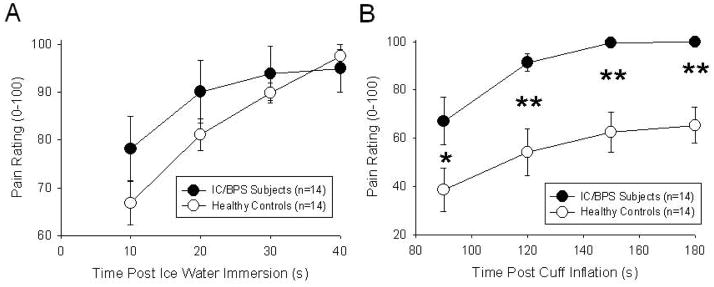

Similar to previous studies12, subjects with IC/BPS were hypersensitive in several quantitative pain measures (Table 1) which included pain with voiding, decreased tolerance of ice water immersion, decreased tolerance of forearm ischemia (Table 1) and increased pain reports with immersion of the hand in ice water and in association with the ischemic task (Figure 2; repeated measure ANOVA p<0.05 for ice water immersion, p<0.001 for ischemic forearm task). Notably, none of the thermal pain measures in the lower extremity were statistically different between the two groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Subjects with the diagnosis of Interstitial Cystitis/Bladder Pain Syndrome (BPS) reported significantly more pain on voiding their bladders and lower tolerance of ischemia and ice water immersion when compared with healthy controls. The two groups did not differ significantly on heat pain measures. See text for specifics of testing.

| Baseline Pain Measures | Interstitial Cystitis/BPS Subjects (n=14) | Healthy Controls (n=14) |

|---|---|---|

| Void Report | 5.2 ± 0.5 ** | 0 ± 0 |

| Ankle Heat Pain Threshold (°C) | 41.2 ± 1.0 | 42.1 ± 0.8 |

| Ankle Heat Pain Tolerance (°C) | 44.9 ± 0.7 | 45.2 ± 0.9 |

| 45 °C Pain Rating (0–100) | 68 ± 10 | 52 ± 6 |

| 49 °C Pain Rating (0–100) | 85 ± 6 | 76 ± 7 |

| Ischemic Tolerance (s) | 116 ± 16 ** | 444 ± 78 |

| Ice Water Tolerance (s) | 23 ± 5 ** | 38 ± 3 |

indicated significant difference from healthy controls with P<0.05 and P<0.01 respectively.

Values are mean ± SEM.

Figure 2.

Subjects with the diagnosis of Interstitial Cystitis reported significantly more pain with immersion of their hand in ice water (A) and during the ischemic forearm task (B) when compared with Healthy Controls. See text for specifics of testing. * and ** indicated significant difference from healthy controls with P<0.05 and P<0.01 respectively. Values are mean ± SEM.

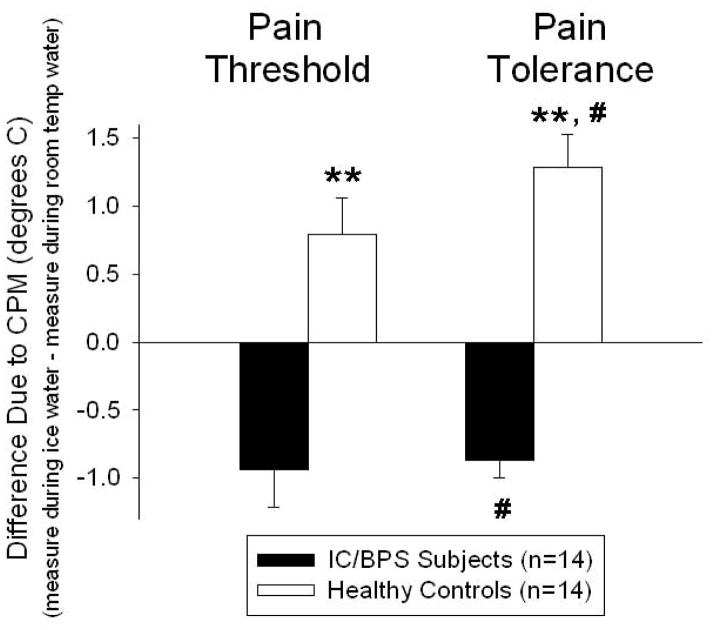

Effects of CPM on Thermal Pain Thresholds/Tolerances

Differential effects of CPM were noted between subjects with IC/BPS and healthy control subjects (Figure 3). Conditioning with ice water immersion led to a statistically significant increase in heat pain tolerance when compared with conditioning with room temperature water immersion in healthy control subjects (paired t-test, p<0.05). In contrast, among IC/BPS subjects, conditioning with ice water immersion led to a statistically significant decrease in heat pain tolerance compared with conditioning with room temperature water immersion (paired t-test, p<0.05). Pain threshold measures were not statistically changed in either subject group although a similar direction of the mean values was noted. When CPM-related change measures were compared between the subjects with IC/BPS and healthy control subjects, there was a highly statistically significant difference between subject groups for both pain thresholds and pain tolerance values (unpaired t-test; P<0.01 for both value sets).

Figure 3.

Differences in hot thermal pain measures due to CPM were calculated as the difference between values measured in the lower extremity while the hand was immersed in ice water minus values measured in the lower extremity while the hand was immersed in room temperature water. Hot thermal pain tolerances due to CPM were statistically different in both subject groups but with a differential effect of CPM (opposite directions) reflected as an increase in difference value in healthy control subjects and as a decrease in difference value in IC/BPS subjects (# indicates difference from measures during room temperature with p<0.05). Hot thermal pain threshold changes due to CPM failed to achieve statistical significance. Due to the different directions of effect of CPM on the two subject groups, a comparison of the CPM effects revealed a statistically significant different effect of subject group on both pain threshold and pain tolerance measures (** indicates difference between two subject groups, p<0.01). Values are mean ± SEM.

One IC/BPS subject was not included in the overall analysis because she differed from the other IC/BPS subjects in that she had undergone a supravescial urinary diversion surgery. It is notable that this subject demonstrated a CPM response similar to the healthy control subjects (a 2.6 °C increase in the pain threshold measures and 0.8 °C increase in the tolerance measure) whereas all other subjects with the diagnosis of IC/BPS has decreases or no changes due to CPM effects. With inclusion of this subject in the data analysis effects on thermal tolerance measures continued to be statistically significant (p<0.05) but effects on thermal threshold were not statistically significant.

Effects of CPM on Thermal Pain Intensity Ratings

Effects of conditioning stimuli on pain intensity responses evoked by two second pulses of 45°C or 49°C heat were neither robust nor statistically significant in either the subjects with IC/BPS or healthy control subjects. Pain intensity ratings in response to a 45°C heat pulse decreased 5.1±1.4 points (on a 100 point scale) in healthy control subjects and increased 2.6±2.6 points in subjects with IC/BPS. Similarly, pain intensity ratings in response to a 49°C heat pulse decreased 0.7±1.3 points in healthy control subjects and increased 2.0±1.3 points in subjects with IC/BPS.

DISCUSSION

The most important finding of the present study was that IC/BPS subjects, as a group, had a quantitatively different effect of CPM in comparison with healthy control subjects. Healthy control subjects, as a group, had CPM effects that were inhibitory, which is consistent with previous investigations of CPM in healthy human and non-human subjects1,18. In contrast, subjects with the diagnosis of IC/BPS had CPM effects that were facilitatory in nature. Multiple chronic pain disorders including chronic joint pain, back pain, chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia, migraines, chronic tension headaches, atypical facial pain, temporomandibular disorder, pancreatitis and irritable bowel syndrome have been demonstrated to have deficits in CPM pain inhibitory effects1,5,7,9,13,19–22 some coupled with facilitation6,23. Bouhassira et al3 found a correlation between the intensity of the CPM deficit and patient reports of pain severity. Other chronic pain disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis, classical trigeminal neuralgia and vestibulodynia13–16 have CPM inhibitory mechanisms that appear intact, so it is unlikely that deficits in these mechanisms are simple sequelae of prolonged pain. It suggests that a predisposition for failed endogenous analgesia may be a requisite neurological condition in these chronic pain disorders. This assertion is supported by prospective studies related to post-operative pain and the development of chronic pain that link pre-existing deficits in CPM-related pain inhibition with subsequent pain development8–10,24. Although tests of CPM effects are not regularly employed clinically, they have potential applicability at predicting the development of chronic pain disorders. This suggests that they might be useful as part of preventive strategies which identify subjects who are at high risk for chronic pain development, therefore justifying certain types of early intervention.

Subjects with IC/BPS commonly have co-morbidities25, including many noted to have similar deficits in CPM inhibitory mechanisms (e.g., migraine, irritable bowel syndrome, fibromyalgia). It is possible that the deficient inhibitory systems observed in the current patient sample reflected the presence of those other disorders in these patients. Other co-morbidities such as depression are not reliably associated with deficits in CPM inhibitory effects7. Since formal measure of co-morbidities was not performed as part of this study, that possibility will have to remain open. However, the robust nature of the findings in the small sample of IC/BPS patients of the present study supports a more direct association of a deficit in CPM inhibitory effects with the symptoms of IC/BPS. Our previous studies of pain sensitivity12 suggested that IC/BPS subjects may form subsets based on baseline thermal sensitivity testing but in the present sample, the effect of CPM was consistently neutral or facilitatory in all but one subject who was already “different” in that she has had a previous supravesical diversion procedure performed. A larger patient sampling may be able to give better evidence for patient subsets. Effects of medical treatments such as opioids may also contribute to changes in CPM and thereby add variability to measures21. It is therefore notable that the five IC/BPS subjects who were not on daily opioids responded in a fashion that was indistinguishable from the IC/PBS subjects on opioids.

Observations noted in human studies examining CPM may allow for a more complete understanding of central nervous system processing of sensory information related to the bladder. The basic science neurophysiology of CPM effects was formally formulated as a theory by Le Bars18. Termed Diffuse Noxious Inhibitory Controls (DNIC), it is a powerful modulatory mechanism related to somatosensory processing. The specific mechanisms of DNIC are described by the presence of at least two populations of spinal neurons, one which is inhibited by heterosegmental noxious stimuli and another population which is not similarly inhibited. Quantitative neurophysiological studies have identified an approximately 50%-50% distribution of two spinal dorsal horn neuronal populations that meet these criteria and which are excited by urinary bladder distension26. Alterations in CPM effects on these spinal neuronal populations have been documented in a model of IC/BPS in which neonatal rats experience bladder inflammation and are allowed to mature to adulthood27. A notable feature of that model was the presence a deficit in the opioidergic antinociceptive system which inhibits the spinal processing of bladder nociception28. The findings of the present human study are important in that they suggest similar mechanisms are present in subjects with IC/BPS. Functional imaging studies related to CPM effects and how they are affected by disease such as in recent studies of irritable bowel syndrome3,5 may also shed light on higher order sites of sensory processing such as brainstem, thalamic and cortical structures. An improved understanding of the neurological changes associated with IC/BPS may allow for improved pharmacological or procedural interventions for the symptoms of that disorder.

Conclusions

An endogenous pain inhibitory system normally observed as CPM was altered in subjects with IC/BPS. This identifies IC/BPS as similar to several other chronic pain disorders such as fibromyalgia and irritable bowel syndrome and suggests that a deficit in endogenous pain control systems may be a contributor to such chronic pain disorders. The clinical implications of these findings are that IC/BPS may be responsive to therapies used in these other disorders. Therapies directed at the restoration of deficient inhibitory systems would seem particularly indicated.

Acknowledgments

Supported by DK51413

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Timothy J Ness, Department of Anesthesiology, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL.

L. Keith Lloyd, Department of Urology, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL.

Roger B. Fillingim, University of Florida College of Dentistry and Gainesville Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Gainesville, FL.

References

- 1.Lewis GN, Rice DA, McNair PJ. Conditioned pain modulation in populations with chronic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain. 2012;13:936–944. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edwards RR, Ness TJ, Weigent DA, et al. Individual differences in diffuse noxious inhibitory controls (DNIC): association with clinical variables. Pain. 2003;106:427–437. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bouhassira D, Moisset X, Jouet P, et al. Changes in the modulation of spinal pain processing are related severity in irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;25:623–e468. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brock C, Olesen SS, Valeriani M, et al. Brain activity in rectosigmoid pain: unraveling conditioning pain modulatory pathways. Clin Neurophysiol. 2012;123:829–837. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2011.07.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heymen S, Maixner W, Whitehead WE, et al. Central processing of noxious somatic stimuli in patients with irritable bowel syndrome compared with healthy controls. Clin Pain. 2010;26:104–109. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181bff800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.King CD, Wong F, Currie T, et al. Deficiency in endogenous modulation of prolonged heat pain in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and temporomandibular disorder. Pain. 2009;143:172–178. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Normand E, Potvin S, Gaumond I, et al. Pain inhibition is deficient in chronic widespread pain but normal in major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72:219–224. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04969blu. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yarnitsky D, Crispel Y, Eisenberg E, et al. Prediction of chronic post-operative pain: pre-operative DNIC testing identifies patients at risk. Pain. 2008;138:22–28. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peters ML, Schmidt AJ, Van de Hout MA, et al. Chronic back pain, acute postoperative pain and the activation of diffuse noxious inhibitory controls (DNIC) Pain. 1992;50:177–187. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90159-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Landau R, Kraft JC, Flint LY, et al. An experimental paradigm for the prediction of post-operative pain (PPOP) J Vis Exp. 2010;35:1671. doi: 10.3791/1671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanno PM, Burks DA, Clemens JQ, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome. J Urol. 2011;185:2162–2170. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.03.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ness TJ, Powell-Boone T, Cannon R, et al. Psychophysical evidence of hypersensitivity in subjects with interstitial cystitis. J Urol. 2005;173:1983–1987. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000158452.15915.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leonard G, Goffaux P, Mathieu D, et al. Evidence of descending inhibition deficits in atypical but not classical trigeminal neuralgia. Pain. 2009;147:217–223. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johannesson U, Nygren de Boussard C, Jansen GB, et al. Evidence of diffuse noxious inhibitory controls (DNIC) elicited by cold noxious stimulation in patients with provoked vestibulodynia. Pain. 2007;130:31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sutton KS, Pukall CF, Chamberlain S. Diffuse noxious inhibitory control function in women with provoked vestibulodynia. Clin J Pain. 2012;28:667–674. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e318243ede4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leffler A-S, Kosek E, Lerndal T, et al. Somatosensory perception and function of diffuse noxious inhibitory controls (DNIC) in patients suffering from rheumatoid arthritis. Eur J Pain. 2002;6:161–176. doi: 10.1053/eujp.2001.0313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pontari MA, Hanno PM, Wein AJ. Logical and systematic approach to the evaluation and management of patients suspected of having interstitial cystitis. Urology suppl. 1997;49:114. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(97)00184-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.LeBars D. The whole body receptive field of dorsal horn multireceptive neurons. Brain Res Rev. 2002;40:29–44. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(02)00186-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meeus M, Nijs J, Van de Wauwer N, et al. Diffuse noxious inhibitory control is delayed in chronic fatigue syndrome: an experimental study. Pain. 2009;139:439–448. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olesen SS, Brock C, Krarup AL, et al. Descending inhibitory pain modulation is impaired in patients with chronic pancreatitis. Clin J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:724–730. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ram KC, Eisenberg E, Haddad M, et al. Oral opioid use alters DNIC but not cold pain perception in patients with chronic pain – new perspective of opioid-induced hyperalgesia. Pain. 2009;139:431–438. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rossi P, Vollono C, Valeriani M, et al. The contribution of clinical neurophysiology to the comprehension of the tension-type headache mechanisms. Clin Neurophysiol. 2011;122:1075–1085. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2010.12.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Tommaso M, Sardaro M, Pecoraro C, et al. Effects of the remote C fibres stimulation induced by capsaicin on the blink reflex in chronic migraine. Cephalgia. 2007;27:881–890. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2007.01357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilder-Smith OH, Schreyer T, Scheffer GJ, et al. Patients with chronic pain after abdominal surgery show less preoperative endogenous pain inhibition and more postoperative hyperalgesia: a pilot study. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2010;24:119–128. doi: 10.3109/15360281003706069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alagiri M, Chottiner S, Ratner V, et al. Interstitial cystitis: unexplained associations with other chronic disease and pain syndromes. Urology suppl. 1997;49:52. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(99)80332-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ness TJ, Castroman P. Evidence for two populations of rat spinal dorsal horn neurons excited by urinary bladder distension. Brain Res. 2001;923:147–156. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)03216-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Randich A, Uzzell TW, DeBerry JJ, et al. Neonatal urinary bladder inflammation produces adult bladder hypersensitivity. J Pain. 2006;7:469–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2006.01.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.DeBerry J, Ness TJ, Robbins MT, et al. Inflammation-induced enhancement of the visceromotor reflex to urinary bladder distention: Modulation by endogenous opioids and the effects of early-in-life experience with bladder inflammation. J Pain. 2007;8(12):914–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]