Abstract

Neuroinflammation is being increasingly recognized as a potential mediator of cognitive impairments in various neurological conditions. Habbas et al. demonstrate that the pro-inflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor alpha signals through astrocytes to alter synaptic transmission and impair cognition in a mouse model of multiple sclerosis.

Inflammation of the CNS is a common feature of nearly all neurological disorders and insults. It is characterized by activation of CNS glial cells and often invasion of peripheral immune cells into the CNS. These cells release a storm of pro-inflammatory cytokines intended to promote immunological responses or further recruit immune cells to eliminate a perceived threat but frequently have negative consequences. In the demyelinating disorder multiple sclerosis (MS), invading autoreactive peripheral immune cells destroy myelin, the lipid insulation around neuronal axons that facilitatesrapid action potential propagation. Motor and sensory deficits are the most common symptoms of MS, though patients also often suffer from cognitive impairments. In fact, cognitive impairments are common to many neuroinflammatory neurological conditions, including Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (Peterson and Toborek, 2014) to name a few. This begs the question: does neuroinflammation contribute to the cognitive impairments that arise in these conditions? A growing body of evidence suggests that this may in fact be the case. One pro-inflammatory cytokine, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), is elevated in MS and other neuroinflammatory neurological conditions (McCoy and Tansey, 2008) and has been implicated in cognitive alterations (Yirmiya and Goshen, 2011). But until now, there has been no demonstration of a mechanism by which this cytokine could affect cognition. In this issue of Cell, Habbas et al. (2015) demonstrate that TNFα signals through astrocytes to alter synaptic strength in the hippocampal formation and contribute to contextual memory deficits observed in a rodent model of MS.

Habbas et al. (2015) investigate the electrophysiological effects of TNFα on the entorhinal cortex-dentate gyrus (EC-DG) synapse in a slice preparation of mouse hippocampal formation, the brain structure responsible for memory formation and spatial navigation. They find that temporary application of TNFα at pathological levels—but not at lower levels—induces a sustained increase in the frequency of presynaptic vesicular release from entorhinal cortical axons, measured as an increase in the frequency of miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs) in dentate gyrus granule cells. How might this synaptic alteration be occurring? The same group previously demonstrated that high levels of extracellular TNFα can trigger release of the conventional neurotransmitter glutamate from astrocytes (Santello et al., 2011) and that astrocytic glutamate acts on presynaptic NMDA glutamate receptors to increase the frequency of presynaptic vesicular release (Jourdain et al., 2007). Habbas et al. (2015) show that pathological TNFα exerts its effects through this pathway. By blocking presynaptic NMDA receptors, they prevent the TNFα-induced increase in mEPSC frequency. To assess the involvement of astrocytes, the authors knock out tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 (TNFR1) in all cell types and re-express it only in astrocytes. As expected, TNFα fails to alter synaptic properties in TNFR1 global knockout mice. However, re-expression of the receptor in astrocytes restores the effect.

Could this mechanism be contributing to cognitive impairment in disease? To model disease-associated cognitive deficits, Habbas et al. (2015) use a mouse model of MS, adoptive transfer experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (AT-EAE), which is induced through injection of CD4+ T cells reactive against myelin proteins. In EAE, cognitive deficits, including spatial memory deficits, are detectable prior to detection of the motor deficits and demyelination that characterize this model (Acharjee et al., 2013), suggesting that the mechanism for cognitive impairment may be distinct from motor pathology. Habbas et al. (2015) similarly find that presymptomatic AT-EAE mice are impaired in contextual fear conditioning, a hippocampal-dependent contextual learning and memory task. In this task, mice are first taught to associate receiving an electric shock with an arena (context). To evaluate memory of this contextual association, mice are returned to the same arena the following day and their fear levels are assessed, as measured by time spent freezing. Indicative of a deficit in contextual memory, AT-EAE mice spend less time freezing.

In congruence with their hypothesis, Habbas et al. (2015) observe elevated hippocampal TNFα levels in AT-EAE mice and a significant increase in mEPSC frequency at EC-DG synapses, comparable to that caused by acute application of pathological levels of TNFα in slice preparation. Demonstrating that TNFα signaling through astrocytes is causative, Habbas et al. (2015) show that AT-EAE does not affect mEPSC frequency in mice lacking TNFR1 globally. However, re-expressing TNFR1 in astrocytes restores this synaptic effect of AT-EAE. This synaptic alteration also requires presynaptic NMDA receptors; blocking these receptors during AT-EAE induction prevents any increase in mEPSC frequency. What about cognition? Remarkably, the authors find that TNFR1 expression in astrocytes alone is sufficient to impair AT-EAE mice in contextual fear conditioning as compared to AT-EAE mice lacking TNFR1 globally.

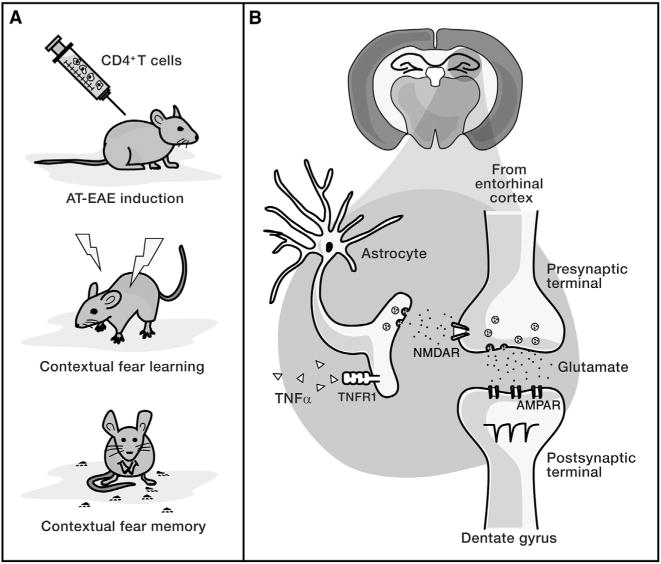

The findings of Habbas et al. (2015) clearly demonstrate that TNFα signaling through astrocytes mediates both synaptic and cognitive changes in AT-EAE, providing the first potential mechanism for how TNFα may be mediating cognitive changes in disease conditions (see Figure 1 for a model of this mechanism). Still, the incidences of the synaptic and behavioral changes observed are correlative. Future studies should assess how increasing frequency of vesicular release at EC-DG synapses could alter hippocampal-dependent contextual learning and memory.

Figure 1. TNFα Acting through Astrocytes Modifies Synapses and Cognition.

(A) AT-EAE mice have deficits in a contextual fear conditioning task, as measured by reduced freezing upon return to a previously aversive context.

(B) Habbas et al. (2015) propose a mechanism for this deficit in which elevated hippocampal TNFα signals through TNFR1 on astrocytes, inducing astrocytic release of glutamate that acts on presynaptic NMDA receptors of entorhinal cortical axons. This results in an increased frequency of presynaptic vesicular release, as measured by increased frequency of mEPSCs in dentate gyrus granule cells.

While neuroinflammation has been implicated not only in the pathogenesis of various neurological conditions but also in associated cognitive impairments, in many instances, its role in disease is not completely clear. Neuroinflammation seems to have a dichotomous role, providing benefits in some circumstances and acting as a detriment in others. Seemingly counterproductively, in mouse models of MS, neuroinflammation contributes to demyelination, yet the remyelination of demyelinated axons requires neuroinflammation (Wee Yong, 2010). Thus, treatments aiming to dampen neuroinflammation in its entirety may have adverse side effects. This highlights the virtue of the work of Habbas et al. (2015) in identifying the downstream mechanisms of how neuroinflammation may contribute to cognitive deficits, providing the opportunity to therapeutically target these mechanisms in isolation.

The authors concentrate on contextual learning and memory and the brain area responsible for this cognitive ability, but TNFα signaling through astrocytes could have various effects throughout the brain. How might TNFα signaling through astrocytes affect synaptic physiology or disease pathology of AT-EAE in other brain regions? Does the same mechanism apply to other areas? It would not be surprising if TNFα could exert differential effects on astrocytes in diverse brain areas given recent developments in our understanding of astrocyte heterogeneity. Like neurons, astrocytes in different brain regions exhibit heterogeneous morphologies and functions (Oberheim et al., 2012). This will be important to ascertain prior to developing therapies targeting this mechanism.

Astrocytes are widely accepted as crucial supporters of synaptic function and synapse formation. However, this study adds to an emerging body of work pointing to a potential but contentious role for astrocytes in synaptic plasticity and cognition (Haydon and Nedergaard, 2015). Like with any mechanism in disease, one wonders if studying the mal functioning system can provide insights into normal system functioning. This group previously showed that physiological levels of TNFα are required for astrocytes to release glutamate and subsequently alter synapses in response to activation of astrocytic purinergic receptors (Santello et al., 2011), demonstrating a role for TNFα and astrocytes at healthy synapses. How TNFα signaling through astrocytes might affect cognition in healthy brains is an exciting future direction.

Acknowledgments

This Preview was supported by the NMSS Research Grant (RG4541A3 and RG5203A4) and NIH/NINDS (R01NS062796). We would like to thank Justin Berot-Burns for his technical assistance with Figure 1.

References

- Acharjee S, Nayani N, Tsutsui M, Hill MN, Ousman SS, Pittman QJ. Brain Behav Immun. 2013;33:164–172. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2013.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habbas S, Santello M, Becker D, Stubbe H, Zappia G, Liaudet N, Klaus FR, Kollias G, Fontana A, Pryce CR, et al. Cell. 2015;163:1730–1741. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.023. this issue. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haydon PG, Nedergaard M. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2015;7:a020438. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a020438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jourdain P, Bergersen LH, Bhaukaurally K, Bezzi P, Santello M, Domercq M, Matute C, Tonello F, Gundersen V, Volterra A. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:331–339. doi: 10.1038/nn1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy MK, Tansey MG. J Neuroinflammation. 2008;5:45. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-5-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberheim NA, Goldman SA, Nedergaard M. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;814:23–45. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-452-0_3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson PK, Toborek M. Neuroinflammation and Neurodegeneration. (New York: Springer); 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Santello M, Bezzi P, Volterra A. Neuron. 2011;69:988–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wee Yong V. Neuroscientist. 2010;16:408–420. doi: 10.1177/1073858410371379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yirmiya R, Goshen I. Brain Behav Immun. 2011;25:181–213. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]