Abstract

Background

Co-morbidity with tuberculosis and HIV is a common cause of mortality in sub-Saharan Africa. In the second Kenya AIDS Indicator Survey, we collected data on knowledge and experience of HIV and tuberculosis, as well as on access to and coverage of relevant treatment services and antiretroviral therapy (ART) in Kenya.

Methods

A national, population-based household survey was conducted from October 2012 to February 2013. Information was collected through household questionnaires, and blood samples were taken for HIV, CD4 cell counts, and HIV viral load testing at a central laboratory.

Results

Overall, 13,720 persons aged 15–64 years participated; 96.7% [95% confidence interval (CI): 96.3 to 97.1] had heard of tuberculosis, of whom 2.0% (95% CI: 1.7 to 2.2) reported having prior tuberculosis. Among those with laboratory-confirmed HIV infection, 11.6% (95% CI: 8.9 to 14.3) reported prior tuberculosis. The prevalence of laboratory-confirmed HIV infection in persons reporting prior tuberculosis was 33.2% (95% CI: 26.2 to 40.2) compared to 5.1% (95% CI: 4.5 to 5.8) in persons without prior tuberculosis. Among those in care, coverage of ART for treatment-eligible persons was 100% for those with prior tuberculosis and 88.6% (95% CI: 81.6 to 95.7) for those without. Among all HIV-infected persons, ART coverage among treatment-eligible persons was 86.9% (95% CI: 74.2 to 99.5) for persons with prior tuberculosis and 58.3% (95% CI: 47.6 to 69.0) for those without.

Conclusions

Morbidity from tuberculosis and HIV remain major health challenges in Kenya. Tuberculosis is an important entry point for HIV diagnosis and treatment. Lack of knowledge of HIV serostatus is an obstacle to access to HIV services and timely ART for prevention of HIV transmission and HIV-associated disease, including tuberculosis.

Keywords: tuberculosis, HIV, co-infection, AIDS indicator survey, HIV/AIDS, HIV/TB

INTRODUCTION

Tuberculosis is the leading cause of death in persons with HIV.1 Co-morbidity from HIV and tuberculosis remains an important public health challenge worldwide but disproportionately affects sub-Saharan Africa. The Word Health Organization (WHO) reported that a total of 8.7 million cases of tuberculosis occurred globally in 2011, with 24% in the African region.2 About 13% of tuberculosis cases worldwide were co-infected with HIV, and approximately 430,000 deaths in HIV-infected persons in 2011 were due to tuberculosis.2 Because HIV infection rates are highest in sub-Saharan Africa, infection with tuberculosis is highly prevalent there, and people living with HIV are at increased risk for developing tuberculosis disease, sub-Saharan Africa is especially affected by comorbidity from HIV and tuberculosis.3 In 2011, sub-Saharan Africa accounted for 79% of all cases of HIV-associated tuberculosis in the world, and 39% of persons with tuberculosis in the region were estimated to be infected with HIV.2

WHO guidelines use tuberculosis as an indicator in the staging of HIV disease, and treatment guidelines now recommend antiretroviral therapy (ART) for all HIV-infected individuals early after tuberculosis diagnosis.4 To reduce the burden of both diseases and to maximize program effectiveness and efficiency, WHO has stressed the importance of strong collaboration between tuberculosis and HIV programs and integration of service delivery to the extent possible for maximal patient convenience.4,5 Key interventions include HIV testing and counseling in tuberculosis clinics, offering HIV prevention services to tuberculosis patients, tuberculosis screening and infection control in HIV clinics, provision of cotrimoxazole to HIV-infected tuberculosis patients, providing ART to patients with HIV-associated tuberculosis early after diagnosis, and offering preventive therapy for tuberculosis after exclusion of active disease to all persons living with HIV.

Kenya ranks 13 of 22 countries with high tuberculosis burden.2 Based on the first Kenya AIDS Indicator Survey (KAIS 2007), the population prevalence of HIV infection was 7.1% among adults and adolescents aged 15–64 years,6 indicating that Kenya ranked fourth in the world in numbers of people living with HIV. The HIV prevalence in tuberculosis patients in Kenya in 2011 was 39%.7 Implementation of integrated tuberculosis and HIV services has improved progressively with uptake of HIV testing in tuberculosis clinics increasing from 60% in 2006 to at least 88% in 2009.8

Planning and implementation of the second Kenya AIDS Indicator Survey (KAIS 2012) offered the opportunity to collect data on aspects of HIV and tuberculosis at the population level and to describe the extent of their association. This article describes population-level knowledge about tuberculosis, demographic and clinical characteristics of persons who report prior tuberculosis disease and treatment for prior tuberculosis, rates of co-infection with tuberculosis and HIV disease, and care and treatment coverage among HIV-infected persons by tuberculosis status. These data should be useful to the Kenya Ministry of Health to inform and prioritize future policies and guidance for addressing the dual epidemics of tuberculosis and HIV.

METHODS

Ethics Statement

The Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) Ethical Review Committee, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Institutional Review Board, and the Committee on Human Research of the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), provided ethical review and approval of the survey protocol.

Study Design

KAIS 2012 was a nationally representative, population-based, cross-sectional household survey of Kenyans aged 18 months to 64 years conducted from October 2012 to February 2013. This survey, described in detail elsewhere, was the second of its kind in Kenya following the first KAIS conducted in 2007.9 It was designed to provide comprehensive data on demographic, behavioral, and biologic characteristics of persons living with HIV, in addition to providing national HIV prevalence estimates and measurement of HIV/AIDS service uptake and need. A household questionnaire was administered to the head of the household to collect household-level information. Sex-specific individual questionnaires were administered for men and women aged 15–64 years.

Information collected included demographic characteristics, sexual and reproductive history, HIV knowledge and attitudes, HIV status and treatment, tuberculosis knowledge, history of tuberculosis disease and treatment, and access to tuberculosis clinic services. Blood was collected for HIV testing at a central laboratory with identifying information removed from specimens. Persons wishing to know their HIV status were offered home-based HIV testing and counseling, with point-of-care CD4 cell count measurement and medical referral proposed for those found to be HIV-positive.

Study Subjects

This analysis is restricted to persons aged 15–64 years. Individuals who were usual residents of the household or spent the night preceding the survey visit in the sampled household were considered eligible for participation. Informed verbal consent was obtained from adults aged 18 years and above or emancipated minors who were pregnant, married, or a parent. Minors aged 15–17 years were asked to provide verbal assent, and their parents or guardians were asked to provide verbal consent before interviews were conducted.

Laboratory Testing

Biologic testing was performed at the National HIV Reference Laboratory. HIV testing was done using Kenya’s validated testing algorithm, which included screening with Vironostika HIV-1/2 UNIF II Plus O Enzyme Immunoassay (bioMérieux, Marcy d’Etoile, France). Positive samples were confirmed with the Murex HIV.1.2.O HIV Enzyme Immunoassay (DiaSorin, SpA, Saluggia, Italy). Discordant results were retested with the 2 assays. Twice discordant results, if they occurred, were tested using a polymerase chain reaction assay (Cobas Amplicor HIV-1 Monitor Test, version 1.5; Roche Molecular Diagnostics, Pleasanton, CA). For quality control, all positive specimens and 5% of negative specimens were retested using the same testing algorithm at the Kenya Medical Research Institute laboratory. For persons with positive HIV tests, measurements of CD4 cell counts (BD FACSCalibur Flow Cytometer; Becton Dickinson Biosciences, San Jose, CA) were performed centrally as well as measurement of HIV viral load (Abbott M2000 Real-Time HIV-1 Assay; Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL).

Data Management and Analysis

Data were collected electronically at the point of interview using tablet computers (Mirus Innovations, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). The data from interview and results of tests conducted in the household were electronically transmitted to a central database in Nairobi where data cleaning, merging, and weighting were done before analysis.

Tuberculosis disease was defined as self-reported history of tuberculosis diagnosed by a doctor or another health professional. Tuberculosis treatment completion was defined by self-report of having taken tuberculosis drugs for 6 or 8 months as prescribed by the national guidelines on treatment of new or recurrent tuberculosis, respectively. HIV viral suppression was defined as HIV RNA concentration <1000 copies per milliliter.

ART coverage was defined as the proportion of treatment-eligible persons who were receiving ART. All persons with a history of tuberculosis who were co-infected with HIV were considered in need of ART, irrespective of CD4 cell count. For persons infected with HIV without a history of tuberculosis, we assumed that those already on ART were treatment eligible, irrespective of current CD4 cell count, and they therefore contributed to both numerator and denominator for calculation of treatment coverage. In addition, persons without prior tuberculosis and not on ART who had a CD4 count ≤350 cells per microliter were considered treatment eligible, consistent with national ART guidelines.10

Univariate and bivariate analyses were conducted to quantify associations between various demographic and behavioral factors with tuberculosis and HIV co-morbidity. Odds ratios (OR), 95% confidence intervals (CI), and P values are presented. Analyses were conducted using SAS software version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). The analysis took into account the cluster survey design, and the estimates were weighted to account for the probability in sampling and adjusted for nonresponse.

RESULTS

A total of 13,720 persons participated in the survey, of whom 5745 (42.0%) men and 7930 (58.0%) women answered questions on tuberculosis and were included in this analysis. Laboratory diagnoses for HIV infection were available for 11,599 (84.8%) persons.

Tuberculosis Knowledge

Overall, 96.7% reported having ever heard of tuberculosis, with significantly fewer women (95.9%) than men (97.7%) having heard of the disease (OR = 0.5; 95% CI: 0.5 to 0.9) (Table 1). More than 90% of individuals in all age groups, in all geographic regions, and of all educational and wealth levels had heard of tuberculosis. The laboratory-diagnosed prevalence of HIV infection in all persons who had heard of tuberculosis was 5.7% (data not shown). In contrast, only 2.9% of persons who had heard of tuberculosis reported a previous diagnosis of HIV; 28% of persons who had heard of tuberculosis had either never been tested for HIV or never received test results.

TABLE 1.

Knowledge About Tuberculosis Among Persons Aged 15–64 Years by Demographic Characteristics and HIV Status, Kenya AIDS Indicator Survey 2012

| All Participants |

Have You Ever Heard of an Illness Called Tuberculosis?* |

Can Tuberculosis be Cured?† |

Can Tuberculosis be Cured in People With HIV?‡ |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unweighted, N | Unweighted, n | Weighted % (95% CI) |

Unweighted, n | Weighted % (95% CI) |

Unweighted, n | Weighted % (95% CI) |

|

| Sex | |||||||

| Men | 5745 | 5613 | 97.7 (97.3 to 98.2) | 4914 | 87.0 (85.6 to 88.3) | 2378 | 49.1 (47.0 to 51.3) |

| Women | 7930 | 7605 | 95.9 (95.3 to 96.6) | 6459 | 84.3 (83.1 to 85.6) | 2816 | 44.3 (42.4 to 46.1) |

| Age category, yrs | |||||||

| 15–24 | 4528 | 4344 | 95.9 (95.2 to 96.6) | 3494 | 79.3 (77.4 to 81.2) | 1428 | 41.6 (39.4 to 43.7) |

| 25–29 | 2138 | 2081 | 97.6 (96.8 to 98.4) | 1808 | 86.5 (84.7 to 88.4) | 802 | 44.6 (41.8 to 47.5) |

| 30–39 | 3099 | 3013 | 97.1 (96.4 to 97.9) | 2707 | 89.3 (87.9 to 90.6) | 1330 | 50.5 (48.0 to 52.9) |

| 40–49 | 2003 | 1934 | 96.8 (95.9 to 97.7) | 1721 | 89.2 (87.5 to 90.8) | 879 | 51.3 (48.2 to 54.4) |

| 50–64 | 1907 | 1846 | 96.7 (95.8 to 97.6) | 1643 | 88.4 (86.6 to 90.2) | 755 | 46.3 (43.0 to 49.6) |

| Highest educational attainment |

|||||||

| No primary | 1560 | 1443 | 91.1 (88.6 to 93.6) | 1208 | 81.8 (78.4 to 85.1) | 398 | 38.5 (33.4 to 43.7) |

| Incomplete primary |

1156 | 1114 | 95.8 (94.3 to 97.4) | 915 | 80.1 (76.8 to 83.4) | 382 | 43.7 (39.2 to 48.2) |

| Complete primary |

4303 | 4203 | 97.7 (97.1 to 98.2) | 3613 | 85.2 (83.8 to 86.7) | 1566 | 42.9 (40.9 to 45.0) |

| Secondary or higher |

6648 | 6450 | 97.0 (96.5 to 97.6) | 5630 | 86.8 (85.5 to 88.1) | 2845 | 49.8 (47.9 to 51.8) |

| Region | |||||||

| Nairobi | 1731 | 1701 | 98.4 (97.5 to 99.2) | 1542 | 90.9 (89.2 to 92.6) | 859 | 56.4 (52.9 to 59.9) |

| Central | 1578 | 1547 | 98.1 (97.4 to 98.8) | 1364 | 89.3 (87.1 to 91.4) | 571 | 41.4 (37.7 to 45.0) |

| Nyanza | 1829 | 1760 | 96.4 (95.0 to 97.7) | 1500 | 85.6 (83.4 to 87.9) | 826 | 55.8 (50.0 to 61.6) |

| Rift Valley North |

1258 | 1203 | 95.6 (93.8 to 97.4) | 1044 | 86.1 (83.0 to 89.2) | 543 | 50.9 (45.1 to 56.7) |

| Rift Valley South |

1220 | 1167 | 95.5 (94.1 to 96.9) | 961 | 82.5 (78.0 to 87.0) | 398 | 40.6 (35.7 to 45.4) |

| Eastern North | 1217 | 1166 | 95.9 (93.7 to 98.1) | 1056 | 91.6 (87.4 to 95.7) | 343 | 33.3 (27.0 to 39.6) |

| Eastern South | 1460 | 1413 | 96.9 (96.0 to 97.8) | 1168 | 82.9 (79.8 to 86.1) | 405 | 35.7 (32.5 to 39.0) |

| Western | 1675 | 1604 | 95.6 (94.5 to 96.8) | 1226 | 75.9 (73.0 to 78.7) | 546 | 44.5 (41.5 to 47.4) |

| Coast | 1707 | 1657 | 97.4 (96.1 to 98.6) | 1512 | 90.8 (88.7 to 92.9) | 703 | 48.7 (44.7 to 52.8) |

| Residence | |||||||

| Rural | 8614 | 8252 | 95.9 (95.3 to 96.5) | 6909 | 83.1 (81.7 to 84.6) | 2910 | 43.7 (41.6 to 45.8) |

| Urban | 5061 | 4966 | 98.0 (97.5 to 98.6) | 4464 | 89.3 (87.9 to 90.8) | 2284 | 50.5 (48.2 to 52.9) |

| Wealth index | |||||||

| Poorest | 2839 | 2688 | 95.0 (93.7 to 96.2) | 2239 | 83.0 (80.5 to 85.4) | 901 | 43.4 (39.2 to 47.5) |

| Second | 2849 | 2730 | 95.7 (94.8 to 96.7) | 2266 | 81.8 (79.9 to 83.8) | 955 | 42.9 (39.9 to 45.9) |

| Middle | 2660 | 2566 | 96.3 (95.4 to 97.3) | 2150 | 82.6 (80.8 to 84.4) | 955 | 45.4 (42.7 to 48.0) |

| Fourth | 2564 | 2511 | 97.9 (97.1 to 98.6) | 2221 | 87.8 (86.1 to 89.5) | 1027 | 45.6 (42.9 to 48.3) |

| Richest | 2745 | 2705 | 98.4 (97.9 to 99.0) | 2480 | 91.5 (90.0 to 93.1) | 1349 | 53.3 (50.6 to 56.1) |

| Reported HIV status |

|||||||

| HIV+ | 363 | 353 | 97.3 (95.5 to 99.0) | 334 | 94.6 (92.2 to 97.0) | 265 | 78.4 (72.1 to 84.7) |

| HIV− | 9214 | 8956 | 97.3 (96.9 to 97.8) | 7817 | 86.7 (85.7 to 87.8) | 3692 | 48.6 (47.0 to 50.3) |

| Never tested/ never received results |

4098 | 3909 | 95.7 (95.0 to 96.5) | 3222 | 82.4 (80.6 to 84.2) | 1237 | 39.1 (36.5 to 41.7) |

| Laboratory HIV results |

|||||||

| HIV+ | 648 | 635 | 97.8 (96.5 to 99.1) | 573 | 89.4 (86.6 to 92.3) | 385 | 67.7 (63.2 to 72.2) |

| HIV− | 10,951 | 10,584 | 96.6 (96.2 to 97.1) | 9095 | 85.2 (84.0 to 86.4) | 3996 | 44.7 (43.1 to 46.4) |

Totals may vary between variables due to missing data.

Among all participants.

Among participants who said they have ever heard about tuberculosis.

Among participants who said that tuberculosis can be cured.

Of those who had heard of tuberculosis, 85.4% said it is curable, with knowledge slightly lower in females than in males (84.3% females vs. 87.0% males; OR = 0.8; 95% CI: 0.7 to 0.9) (Table 1). Knowledge that tuberculosis is curable was significantly associated with educational level; 86.8% of persons with secondary of higher level of education knew it to be curable compared with 81.8% of those with no primary education (OR = 1.5; 95% CI: 1.2 to 1.9). Persons aged 25 years and older were significantly more likely than youth aged 15–24 years to have correct knowledge (P < 0.001), and there were significant differences in knowledge by region, with a range of 90.9% of persons in Nairobi being aware of tuberculosis curability to 75.9% in Western region (P < 0.001) and by urban (89.3%) versus rural (83.1%) residence (OR = 1.7; 95% CI: 1.4 to 2.0).

Of people who self-reported HIV-positive status, 94.6% knew that tuberculosis is curable, a higher proportion than for any other category and significantly higher than for those self-reporting as HIV-negative (86.7%) (OR = 2.8; 95% CI: 1.7 to 4.6) (Table 1). Persons with laboratory-diagnosed HIV infection were also significantly more likely than HIV-negative persons to have correct knowledge, although the difference was less marked (89.4% vs. 85.2%; OR = 1.5; 95% CI: 1.1 to 2.0).

Overall, 46.4% of persons who knew tuberculosis is curable were aware that it can also be cured in people living with HIV. This knowledge was significantly associated with self-reported HIV-positive status; 78.4% persons self-reporting to be HIV-positive were aware versus 48.6% among persons self-reporting as HIV-negative (OR = 4.0; 95% CI: 2.8 to 5.7) and 39.1% among those who had never been tested or received results (OR = 0.7 compared to self-reported HIV-negatives; 95% CI: 0.6 to 0.8) (Table 1). Persons with laboratory-diagnosed HIV infection were also more likely than those with HIV-negative laboratory results to know that tuberculosis is curable in persons living with HIV [67.7% versus 44.7% (OR = 2.6; 95% CI: 2.1 to 3.2)]. Age, educational level, wealth index, region, and urban versus rural residence were all significantly associated with knowing tuberculosis can be cured among HIV-positive persons (P < 0.001). The highest levels of knowledge were in Nyanza (55.8%) and Nairobi (56.4%) regions.

History of Tuberculosis and Tuberculosis Treatment

A total of 271 (2.0%) participants who had ever heard of tuberculosis reported ever having had tuberculosis (Table 2). Significantly fewer women than men had a history of tuberculosis, 1.6% versus 2.4% (OR = 0.7; 95% CI: 0.5 to 0.9). The proportion of persons reporting prior tuberculosis increased with age, from 0.6% in those younger than aged 25 years to 3.5% in persons aged 50 years or older (P < 0.0001). There were significant differences in history of tuberculosis disease by geographic region, with the highest rate (3.8%) found in Nyanza (P = 0.0002), but there was no association between a self-reported history of tuberculosis and level of education, wealth index, or residence.

TABLE 2.

History and Treatment of Tuberculosis Among Persons Aged 15–64 Years Who Had Ever Heard of Tuberculosis by Demographic Characteristics and HIV Status, Kenya AIDS Indicator Survey 2012

| All Participants Who Said They Ever Heard of Tuberculosis |

Ever Had Tuberculosis* |

Ever Been Treated for the Tuberculosis† |

Completed TB Treatment‡ |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unweighted, N | Unweighted, n | Weighted % (95% CI) |

Unweighted, n | Weighted % (95% CI) |

Unweighted, n | Weighted % (95% CI) |

|

| Total | 13,195 | 271 | 2.0 (1.7 to 2.2) | 261 | 96.2 (93.7 to 98.8) | 168 | 81.4 (75.0 to 87.9) |

| Sex | |||||||

| Men | 5604 | 139 | 2.4 (2.0 to 2.8) | 133 | 95.4 (91.7 to 99.1) | 84 | 78.9 (70.0 to 87.7) |

| Women | 7591 | 132 | 1.6 (1.3 to 2.0) | 128 | 97.1 (93.8 to 100) | 84 | 84.4 (76.2 to 92.6) |

| Age category, yrs | |||||||

| 15–24 | 4335 | 27 | 0.6 (0.3 to 0.8) | 25 | 87.8 (71.7 to 100) | 14 | 62.7 (39.1 to 86.3) |

| 25–29 | 2079 | 29 | 1.4 (0.8 to 1.9) | 26 | 90.1 (79.3 to 100) | 20 | 89.2 (77.1 to 100) |

| 30–39 | 3011 | 81 | 2.7 (2.0 to 3.4) | 79 | 97.3 (93.5 to 100) | 51 | 81.7 (70.8 to 92.6) |

| 40–49 | 1928 | 67 | 3.1 (2.2 to 4.0) | 66 | 99.8 (99.5 to 100) | 45 | 89.0 (77.1 to 100) |

| 50–64 | 1842 | 67 | 3.5 (2.6 to 4.4) | 65 | 97.6 (94.3 to 100) | 38 | 77.4 (64.0 to 90.7) |

| Highest educational attainment |

|||||||

| No primary | 1436 | 34 | 1.8 (1.0 to 2.6) | 33 | 99.4 (98.3 to 100) | 16 | 79.0 (53.9 to 100) |

| Incomplete primary | 1113 | 21 | 2.2 (1.3 to 3.2) | 20 | 91.9 (76.6 to 100) | 12 | 70.9 (46.5 to 95.2) |

| Complete primary | 4193 | 74 | 1.7 (1.3 to 2.1) | 69 | 92.5 (85.9 to 99.1) | 44 | 76.1 (63.8 to 88.5) |

| Secondary or higher | 6445 | 142 | 2.1 (1.7 to 2.5) | 139 | 98.4 (96.4 to 100) | 96 | 85.7 (78.9 to 92.6) |

| Region | |||||||

| Nairobi | 1700 | 35 | 2.2 (1.5 to 2.9) | 35 | 100 | 24 | 83.6 (65.6 to 100) |

| Central | 1544 | 32 | 1.9 (1.3 to 2.6) | 30 | 92.8 (82.6 to 100) | 21 | 82.5 (65.3 to 99.8) |

| Nyanza | 1756 | 66 | 3.8 (2.7 to 4.8) | 63 | 95.8 (91.1 to 100) | 43 | 87.1 (75.3 to 98.8) |

| Rift Valley North | 1201 | 16 | 1.4 (0.7 to 2.0) | 15 | 91.8 (76.7 to 100) | 11 | 83.4 (60.1 to 100) |

| Rift Valley South | 1167 | 18 | 1.6 (0.6 to 2.5) | 18 | 100 | 10 | 71.9 (50.7 to 93.0) |

| Eastern North | 1165 | 32 | 2.9 (1.8 to 4.0) | 31 | 97.7 (93.2 to 100) | 18 | 89.0 (74.3 to 100) |

| Eastern South | 1410 | 21 | 1.4 (0.8 to 2.1) | 21 | 100 | 13 | 83.4 (61.6 to 100) |

| Western | 1603 | 25 | 1.6 (0.9 to 2.3) | 23 | 93.1 (83.5 to 100) | 10 | 62.8 (34.1 to 91.5) |

| Coast | 1649 | 26 | 1.5 (0.9 to 2.0) | 25 | 95.0 (85.0 to 100) | 18 | 86.5 (69.2 to 100) |

| Residence | |||||||

| Rural | 8238 | 167 | 2.0 (1.6 to 2.4) | 160 | 95.9 (92.5 to 99.2) | 98 | 80.6 (72.5 to 88.7) |

| Urban | 4957 | 104 | 1.9 (1.5 to 2.3) | 101 | 96.9 (93.2 to 100) | 70 | 82.8 (72.3 to 93.3) |

| Wealth index | |||||||

| Poorest | 2683 | 61 | 2.1 (1.3 to 2.8) | 60 | 99.8 (99.5 to 100) | 33 | 77.3 (65.4 to 89.3) |

| Second | 2722 | 61 | 2.1 (1.5 to 2.8) | 59 | 95.6 (89.4 to 100) | 37 | 77.5 (64.1 to 90.8) |

| Middle | 2562 | 40 | 1.7 (1.0 to 2.3) | 37 | 93.4 (86.0 to 100) | 26 | 85.9 (72.0 to 99.7) |

| Fourth | 2506 | 65 | 2.4 (1.8 to 3.0) | 62 | 94.4 (88.2 to 100) | 43 | 87.0 (76.0 to 98.1) |

| Richest | 2704 | 44 | 1.6 (1.0 to 2.1) | 43 | 98.2 (94.6 to 100) | 29 | 80.3 (63.1 to 97.5) |

| Reported HIV status | |||||||

| HIV+ | 352 | 74 | 21.0 (16.1 to 25.8) | 73 | 99.0 (96.9 to 100) | 56 | 93.5 (86.1 to 100) |

| HIV− | 8946 | 155 | 1.7 (1.4 to 2.0) | 148 | 95.3 (91.4 to 99.1) | 94 | 79.3 (70.9 to 87.7) |

| Never tested/never received results |

3897 | 42 | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.4) | 40 | 94.0 (85.9 to 100) | 18 | 62.3 (40.6 to 84.1) |

| Laboratory HIV result | |||||||

| HIV+ | 633 | 75 | 11.6 (8.9 to 14.3) | 75 | 100 | 59 | 92.0 (83.8 to 100) |

| HIV− | 10,570 | 159 | 1.4 (1.1 to 1.7) | 150 | 94.2 (90.1 to 98.3) | 86 | 73.5 (64.6 to 82.5) |

Totals may vary between variables due to missing data.

Among all patients who have ever heard of tuberculosis.

Among patients who said they have ever had been told by a doctor that they had tuberculosis.

Among patients who said that they had been treated for tuberculosis and were not currently on treatment.

Overall, 96.2% of persons reporting prior tuberculosis also reported receiving treatment for it, and of those who received treatment, 81.4% reported completing it (Table 2). Receipt of tuberculosis treatment was significantly higher in persons with laboratory-diagnosed HIV infection (P < 0.0001) but not self-reported HIV infection. Among those treated, completion rates were significantly higher in those self-reporting HIV-positive status than those self-reporting HIV-negative status (93.5% vs. 79.3%, P = 0.02) or laboratory-diagnosed as HIV-positive compared to a laboratory-diagnosed as HIV-negative (92.0% vs. 73.5%, P = 0.02) (Table 2).

Among persons with laboratory-diagnosed and self-reported HIV infection, respectively, 11.6% (95% CI: 8.9 to 14.3) and 21.0% (95% CI: 16.1 to 25.8) reported ever having had tuberculosis (Table 2) compared with 1.4% (95% CI: 1.1 to 1.7) and 1.7% (95% CI: 1.4 to 2.0), respectively, of persons diagnosed or self-reported as HIV-negative. The respective HIV prevalence levels of laboratory-diagnosed and self-reported HIV infection in persons with prior tuberculosis were 33.2% (95% CI: 26.2 to 40.2) and 33.4% (95% CI: 26.7 to 40.1) compared with 5.1% (95% CI: 4.5 to 5.8) and 3.2% (95% CI: 2.6 to 3.8), respectively, in those without prior tuberculosis (data not shown). Highly significant associations between HIV infection, laboratory-diagnosed or self-reported, and a history of prior tuberculosis were observed [for laboratory-diagnosed HIV infection: OR = 9.2; 95% CI: 6.6 to 12.8 (Table 3) and for self-reported HIV infection: OR = 15.4; 95% CI: 10.8 to 21.9] (Table 4).

TABLE 3.

Association Between History of Tuberculosis and Laboratory-Diagnosed HIV Status Among Persons Aged 15–64 Years Who Had Ever Heard of Tuberculosis, Kenya AIDS Indicator Survey 2012

| History of Tuberculosis |

No History of Tuberculosis |

Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HIV+ | 75 | 558 | 633 |

| HIV− | 159 | 10,411 | 10,570 |

| Total | 234 | 10,969 | 11,203 |

OR = 9.2 (95% CI: 6.6 to 12.8).

TABLE 4.

Association Between History of Tuberculosis and Self-Reported HIV Status Among Persons Aged 15–64 Years Who Had Ever Heard of Tuberculosis, Kenya AIDS Indicator Survey 2012

| History of Tuberculosis | No History of Tuberculosis | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HIV+ | 74 | 278 | 352 |

| HIV− | 155 | 8791 | 8966 |

| Total | 229 | 9089 | 9318 |

OR = 15.4 (95% CI: 10.8 to 21.9).

Factors Associated With HIV Co-infection in Persons With History of Tuberculosis

Compared with HIV-uninfected persons with prior tuberculosis, those co-infected with HIV and tuberculosis were more likely to be women (OR = 2.1; 95% CI: 1.1 to 3.9) (Table 5). HIV-infected persons with prior tuberculosis were more likely to be urban residents than HIV-uninfected persons with such a history (OR = 2.4; 95% CI: 1.2 to 4.5) and were more likely to be from Nyanza region (compared to Nairobi region; OR = 3.1; 95% CI: 1.1 to 8.5). HIV co-infected persons were wealthier than HIV-uninfected persons with prior tuberculosis (P = 0.006).

TABLE 5.

History of Tuberculosis by Laboratory-Diagnosed HIV Status and Associations With Demographic Characteristics and Self-Reported HIV Status Among Persons Aged 15–64 Years Who Had Ever Heard of Tuberculosis, Kenya AIDS Indicator Survey 2012

| TB+/HIV+ |

TB+/HIV− |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Select Variables | Unweighted, n (N = 75) |

Weighted % (95% CI) |

Unweighted, n (N = 151) |

Weighted % (95% CI) |

OR (95% CI) | P |

| Sex | ||||||

| Men | 30 | 46.0 (34.9 to 57.2) | 88 | 64.4 (55.5 to 73.2) | 1.0 | — |

| Women | 45 | 54.0 (42.8 to 65.1) | 71 | 35.6 (26.8 to 44.5) | 2.1 (1.1 to 3.9) | 0.0173 |

| Age category, yrs | ||||||

| 15–24 | 0 | — | 27 | 17.6 (11.0 to 24.1) | — | <0.0001 |

| 25–29 | 5 | 5.5 (0 to 11.2) | 17 | 12.1 (5.7 to 18.4) | 1.0 | — |

| 30–39 | 29 | 38.5 (26.8 to 50.2) | 43 | 28.8 (20.2 to 37.5) | 3.0 (0.9 to 10.0) | 0.0721 |

| 40–49 | 18 | 23.6 (13.8 to 33.4) | 33 | 19.2 (12.0 to 26.4) | 2.9 (0.8 to 10.5) | 0.1019 |

| 50–64 | 23 | 32.4 (19.8 to 45.0) | 39 | 22.4 (14.9 to 29.8) | 3.3 (1.0 to 11.4) | 0.0577 |

| Highest educational attainment | ||||||

| No primary | 4 | 3.0 (0 to 6.1) | 24 | 5.3 (2.2 to 8.4) | 1.0 | — |

| Incomplete primary | 3 | 5.4 (0 to 11.7) | 15 | 10.3 (5.0 to 15.5) | 1.1 (0.2 to 7.1) | 0.9168 |

| Complete primary | 18 | 24.1 (12.7 to 35.5) | 46 | 30.0 (22.3 to 37.6) | 1.6 (0.4 to 6.3) | 0.5361 |

| Secondary or higher | 50 | 67.6 (55.4 to 79.8) | 74 | 54.4 (45.6 to 63.2) | 2.4 (0.7 to 8.5) | 0.1695 |

| Region | ||||||

| Nairobi | 7 | 8.9 (3.0 to 14.8) | 19 | 11.8 (8.0 to 15.5) | 1.0 | — |

| Central | 9 | 10.7 (4.3 to 17.1) | 21 | 15.4 (10.9 to 19.9) | 1.0 (0.3 to 3.5) | 0.9787 |

| Nyanza | 32 | 44.6 (32.9 to 56.3) | 26 | 18.6 (12.8 to 24.5) | 3.1 (1.1 to 8.5) | 0.0282 |

| Rift Valley North | 4 | 5.5 (0.2 to 10.9) | 8 | 7.9 (4.7 to 11.0) | 0.9 (0.2 to 4.4) | 0.9234 |

| Rift Valley South | 7 | 12.6 (4.0 to 21.1) | 11 | 13.3 (5.2 to 21.4) | 1.2 (0.3 to 5.6) | 0.8248 |

| Eastern North | 4 | 0.7 (0 to 1.3) | 25 | 2.2 (1.6 to 2.8) | 0.4 (0.1 to 1.6) | 0.1933 |

| Eastern South | 3 | 7.3 (0 to 14.9) | 15 | 12.6 (8.7 to 16.6) | 0.7 (0.1 to 3.7) | 0.7094 |

| Western | 3 | 4.5 (0 to 9.0) | 19 | 11.1 (8.5 to 13.8) | 0.6 (0.1 to 2.5) | 0.4907 |

| Coast | 6 | 5.3 (1.3 to 9.3) | 15 | 7.1 (4.8 to 9.4) | 1.0 (0.3 to 3.9) | 0.9920 |

| Residence | ||||||

| Rural | 38 | 51.2 (39.4 to 63.0) | 109 | 70.6 (64.2 to 77.0) | 1.0 | — |

| Urban | 37 | 48.8 (37.0 to 60.6) | 50 | 29.4 (23.0 to 35.8) | 2.4 (1.2 to 4.5) | 0.0100 |

| Wealth index | ||||||

| Poorest | 10 | 13.6 (5.3 to 21.9) | 44 | 24.0 (14.1 to 33.8) | 1.0 | — |

| Second | 11 | 15.6 (6.0 to 25.2) | 41 | 25.5 (17.2 to 33.8) | 1.2 (0.4 to 3.4) | 0.7421 |

| Middle | 17 | 26.6 (13.4 to 39.8) | 17 | 12.2 (6.2 to 18.2) | 4.3 (1.5 to 11.9) | 0.0055 |

| Fourth | 23 | 25.1 (15.0 to 35.3) | 35 | 23.6 (15.4 to 31.7) | 2.3 (0.8 to 6.5) | 0.1065 |

| Richest | 14 | 19.0 (9.0 to 29.1) | 22 | 14.8 (8.3 to 21.3) | 2.5 (0.8 to 7.5) | 0.1088 |

| Reported HIV status | ||||||

| HIV+ | 57 | 77.2 (66.4 to 88.0) | 6 | 3.8 (0.6 to 7.0) | 97.8 (33.9 to 282.0) | <0.0001 |

| HIV− | 12 | 16.2 (7.4 to 25.0) | 124 | 76.4 (68.8 to 84.0) | 1.0 | — |

| Never tested/never received results | 5 | 6.6 (0 to 14.4) | 29 | 19.8 (12.7 to 26.8) | 2.0 (0.6 to 6.6) | 0.2660 |

Totals may vary between variables due to missing data. Due to rounding errors, the sum of stratum-specific estimates may not equal 100%.

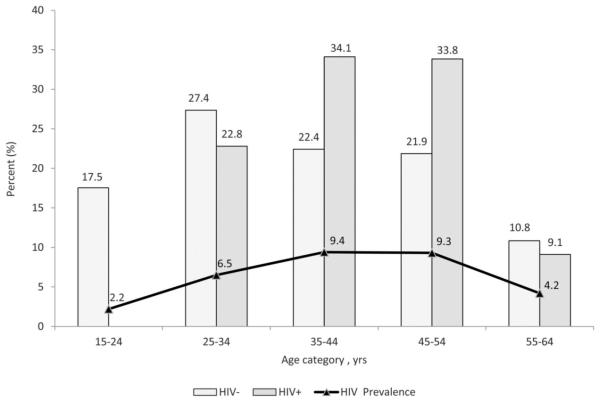

The proportion of HIV-uninfected persons with history of tuberculosis peaked among persons aged 25–34 years, at 27.4%. In contrast, the proportion of HIV-infected persons with a history of tuberculosis peaked higher and later among persons aged 35–44 years (34.1%) and 45–54 years (33.8%). The latter distribution corresponded with the age distribution for HIV prevalence in the population, where HIV prevalence peaked among persons aged 35–54 years, at 9.4% (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

Distribution of age by HIV status and HIV prevalence among persons aged 15–64 years with history of tuberculosis, Kenya AIDS Indicator Survey 2012.

Awareness of HIV Serostatus and Access to HIV Care and ART

Overall, 47% of persons with HIV infection were aware of their infection.11 However, knowledge of HIV infection was significantly higher among persons with prior tuberculosis (77.2%) compared with persons without prior tuberculosis (42.9%) (Table 6). Among persons who were aware of their HIV infection, those with prior tuberculosis were more likely to be in HIV care (99.0%) than those without prior tuberculosis (89.8%) (P < 0.0001).

TABLE 6.

Awareness of HIV-Positive Status and HIV Treatment Characteristics Among Laboratory-Diagnosed HIV-Infected Persons Aged 15–64 Years by History of Tuberculosis, Kenya AIDS Indicator Survey 2012

| HIV+/TB+ |

HIV+/TB− |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unweighted, n | Weighted % (95% CI) |

Unweighted, n | Weighted % (95% CI) |

P | |

| Knowledge of HIV+ status | <0.0001 | ||||

| Aware of HIV+ | 59 | 77.2 (66.8 to 87.6) | 238 | 42.9 (36.9 to 48.8) | |

| Not aware | 16 | 22.8 (12.4 to 33.2) | 320 | 57.1 (51.2 to 63.1) | |

| Total | 75 | 538 | |||

| Care and treatment among those aware of HIV+ status | <0.0001 | ||||

| Aware of HIV+, in care and on ART | 56 | 95.7 (92.0 to 99.4) | 144 | 61.2 (54.8 to 67.6) | |

| Aware of HIV+, in care and not on ART | 3 | 4.3 (0.6 to 8.0) | 71 | 28.6 (22.5 to 34.7) | |

| Aware of HIV+, not in care and not on ART | 0 | — | 23 | 10.2 (6.6 to 13.8) | |

| Total | 59 | 238 | |||

| Care and treatment among all persons HIV+ | <0.0001 | ||||

| Aware of HIV+, in care and on ART | 56 | 73.9 (63.4 to 84.3) | 144 | 26.2 (21.3 to 31.1) | |

| Aware of HIV+, in care and not on ART | 3 | 3.3 (0.5 to 6.2) | 71 | 12.3 (9.0 to 15.5) | |

| Aware of HIV+, not in care and not on ART | 0 | — | 23 | 4.4 (2.8 to 6.0) | |

| Not aware of HIV+ | 16 | 22.8 (12.4 to 33.2) | 320 | 57.1 (51.2 to 63.1) | |

| Total | 75 | 558 | |||

| Coverage of ART among persons aware of HIV+, in care, and eligible for ART* |

<0.0001 | ||||

| In care and on ART | 29 | 100† | 80 | 88.6 (81.6 to 95.7) | |

| In care and not on ART | 0 | — | 8 | 11.4 (4.3 to 18.4) | |

| Total | 29 | 88 | |||

| Coverage of ART among all persons HIV+ and eligible for ART* |

<0.0001 | ||||

| In care and on ART | 29 | 86.9 (74.2 to 99.5)† | 80 | 58.3 (47.6 to 69.0) | |

| In care and not on ART | 0 | — | 8 | 7.5 (2.8 to 12.2) | |

| Not aware of HIV+ | 4 | 13.1 (0.5 to 25.8)† | 46 | 34.2 (24.4 to 43.9) | |

| Total | 33 | 134 | |||

| Viral load | 0.7177 | ||||

| Aware of HIV+, on ART, suppressed‡ | 43 | 76.6 (67.3 to 85.8) | 103 | 74.5 (68.0 to 81.0) | |

| Aware of HIV+, on ART, not suppressed | 13 | 23.4 (14.2 to 32.7) | 36 | 25.5 (19.0 to 32.0) | |

| Total | 56 | 139 | |||

Eligibility for ART defined as CD4 ≤350 cells per microliter, prior history of tuberculosis, and ever taking ART.

Estimates based on sample sizes of <50 observations and may be unreliable.

HIV RNA concentration <1000 copies per milliliter.

Among all HIV-infected persons, the proportion of those with and without prior tuberculosis who were on ART were 73.9% and 26.2%, respectively. Persons with prior tuberculosis therefore accounted for 28.8% (56/200) of all those taking ART. For persons who were aware of their HIV status, the respective proportions taking ART were 95.7% for those with prior tuberculosis and 61.2% for those without prior tuberculosis (P < 0.0001).

To estimate ART coverage for HIV-infected persons without prior tuberculosis who were in care, we examined persons with CD4 counts available and considered all persons on ART as treatment eligible, as well as those untreated who had a CD4 cell count ≤350 cells per microliter. The proportion of treatment-eligible persons without prior tuberculosis who were in care and receiving ART was 88.6%.

For both groups, ART coverage was lower when was assessed among all HIV-infected persons eligible for treatment, including those without knowledge of HIV serostatus. Overall coverage was 86.9% for persons with prior tuberculosis and 58.3% for those without prior tuberculosis (P < 0.0001). Approximately, three-quarters of HIV-infected persons on ART had achieved virologic suppression (76.6% among persons with prior tuberculosis and 74.5% among persons without prior tuberculosis).

DISCUSSION

KAIS 2012 gives insight into the epidemics of HIV and tuberculosis and their association in Kenya. Overall, 5.6% of adults and adolescents aged 15 to 64 years were infected with HIV in the survey,11 and 2% of those who had heard of tuberculosis reported ever having had tuberculosis. In 2011, the Kenya Ministry of Health’s Division of Leprosy, Tuberculosis and Lung Disease reported a total of 103,981 cases of tuberculosis nationally.7 In KAIS 2012, almost one third of persons who reported prior tuberculosis were infected with HIV compared with 5.1% of persons without prior tuberculosis. In addition, 11.6% of persons with laboratory-diagnosed HIV infection reported having had tuberculosis previously. In contrast, only 1.4% of HIV-negative persons reported prior tuberculosis, indicative of the greatly increased relative risk for this disease that HIV infection confers at a population level. The association between HIV and tuberculosis was even stronger for the smaller group of persons self-reporting as HIV-positive, of whom 1 of 5 reported prior tuberculosis.

Reflective of the distribution of HIV infection itself,6 persons with a history of HIV-associated tuberculosis were more likely than those with HIV-negative tuberculosis to be female, older, and residents of urban settings and Nyanza region, where HIV prevalence is high. They also were slightly wealthier. Just over one-quarter of all HIV-infected persons taking ART had a history of prior tuberculosis, which for many was likely the indicator disease leading to HIV diagnosis and care, including ART. Since tuberculosis frequently occurs relatively early in the natural history of HIV infection,2 tuberculosis services may be playing an analogous role to those for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV, which are a frequent entry point for HIV care among women.

Although awareness of tuberculosis in the general population in Kenya was high, less than half of study participants knew that tuberculosis was curable in persons living with HIV. The finding that HIV-infected people, especially those reporting their own HIV infection, had significantly higher levels of knowledge suggests that many may have acquired this understanding from their own disease experience. Nonetheless, as only about two-thirds to three-quarters of persons with HIV knew that HIV-associated tuberculosis was curable, education about tuberculosis should constitute an important element of HIV/AIDS treatment literacy.

KAIS 2012 provided insight into access to treatment and care for HIV and tuberculosis. More than 95% of participants with self-reported prior tuberculosis reported receiving anti-tuberculosis therapy, and more than 80% of the latter reported completing it. HIV treatment programs would benefit from emulating tuberculosis programs’ approach to cohort analysis of outcomes for all persons diagnosed with HIV.12 Although the process would be more complex because of the need for lifelong ART, analogous treatment outcomes can be defined and viral load suppression (or lack of it) could replace cure (or failure) in tuberculosis treatment as an outcome measure of HIV therapy.

KAIS 2012 reinforced observations from KAIS 2007 concerning the importance of individuals knowing their HIV serostatus.6 Provided people were aware of their HIV infection, access to HIV care and uptake of ART for those eligible were high. For persons who reported that they were infected with HIV, all persons with prior tuberculosis and approximately 90% without prior tuberculosis were in HIV care, and a similar proportion of such persons who were eligible for treatment were receiving ART. However, taking into account undiagnosed HIV infection, only about three-quarters of all HIV-infected persons with prior tuberculosis were in care compared to about 40% of HIV-infected persons without prior tuberculosis. Taking ART eligibility into account for all HIV-infected persons, including those undiagnosed and not in care, ART coverage was higher at 87% for persons with and 56% for persons without prior tuberculosis. In the broader KAIS sample, ART coverage regardless of tuberculosis knowledge fell in between these 2 estimates, at 61%.13 Among persons who accessed ART, more than 70% were virally suppressed. These estimates show progress over a few years but are lower than coverage estimates from programmatic data or modeling efforts and fall short of universal access.14

In this analysis, approximately half of persons living with HIV were unaware of their HIV infection and thus unable to access potentially life-saving services.14 HIV testing is the essential entry into HIV care and treatment,15 but our data suggest that for many people tuberculosis disease may have been the reason for HIV diagnosis. If ART is to prevent morbidity including tuberculosis, HIV testing and ART provision must occur before people develop immunodeficiency-associated disease.16,17 WHO issued new guidelines in 2013 advocating ART for all HIV-infected persons with CD4 cell counts of 500 cells per microliter or below. Considerable prevention and therapeutic benefit occur at the population level with scale-up of ART initiated at the lower CD4 cell count thresholds still applied in most countries.18,19 Whatever future policy decisions are made,4 the critical requirements are widespread HIV testing, greatly increased knowledge of HIV serostatus, and timely implementation of ART, especially for those most immunosuppressed.

There were several limitations to the present study. History of tuberculosis was self-reported, and different clinical categories, such as new cases, recurrences, treatment failures, and drug-resistant cases, could not be explored. Self-reports of HIV infection were not necessarily accurate, and recall bias could have influenced participants’ reporting of previously received testing, treatment and care services, and results. Despite its public health importance, tuberculosis is still a relatively rare event and numbers were small for further analyses. Cross-sectional surveys like KAIS 2012 have intrinsic biases because participants likely differ from nonparticipants who may have been excluded because of factors relevant to both HIV infection and tuberculosis, including through hospitalization or death, resulting in potential under-estimation of the true burden of tuberculosis and HIV in the population. North Eastern region, the region of the country with the lowest HIV prevalence and a relatively small population, was excluded for reasons of insecurity, so the study was not perfectly representative of the whole country. Despite these and other limitations, this national survey has given a unique assessment of the tuberculosis and HIV situation in Kenya not available through routine surveillance or program evaluations.

Despite substantial progress since KAIS 2007,6 KAIS 2012 highlights important areas for improvement. Without universal knowledge of HIV serostatus in this country with a generalized HIV epidemic, the full benefit of ART for prevention of HIV transmission as well as of morbidity and death, including from tuberculosis, will not be realized.20,21 Much greater emphasis on preventing tuberculosis among persons living with HIV is required.

National surveys of tuberculosis itself, for assessment of prevalence, evaluation of case finding, and tracking of anti-tuberculous drug resistance, must also be supported in high burden countries, such as Kenya. The inclusion of tuberculosis-specific data in KAIS 2012 should lead to increased understanding, enhanced commitment to policy setting and planning for both HIV and tuberculosis, and improved services for both diseases, which remain among the most important health challenges in Kenya and on the African continent.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the interviewers, counselors, phlebotomists, and their supervisors for their work during KAIS data collection. The authors also gratefully acknowledge all persons who participated in this national survey. The authors would also like to thank George Rutherford, Lucy Ng’ang’a, Anthony Waruru, and Mike Grasso for discussing and reviewing the manuscript, and the KAIS Study Group for their contribution to the design of the survey and collection of the data set: Willis Akhwale, Sehin Birhanu, John Bore, Angela Broad, Robert Buluma, Thomas Gachuki, Jennifer Galbraith, Anthony Gichangi, Beth Gikonyo, Margaret Gitau, Joshua Gitonga, Mike Grasso, Malayah Harper, Andrew Imbwaga, Muthoni Junghae, Mutua Kakinyi, Samuel Mwangi Kamiru, Nicholas Owenje Kandege, Lucy Kanyara, Yasuyo Kawamura, Timothy Kellogg, George Kichamu, Andrea Kim, Lucy Kimondo, Davies Kimanga, Elija Kinyanjui, Stephen Kipkerich, Danson Kimutai Koske, Boniface O. K’Oyugi, Veronica Lee, Serenita Lewis, William Maina, Ernest Makokha, Agneta Mbithi, Joy Mirjahangir, Ibrahim Mohamed, Rex Mpazanje, Silas Mulwa, Nicolas Muraguri, Patrick Murithi, Lilly Muthoni, James Muttunga, Jane Mwangi, Mary Mwangi, Sophie Mwanyumba, Francis Ndichu, Anne Ng’ang’a, James Ng’ang’a, John Gitahi Ng’ang’a, Lucy Ng’ang’a, Carol Ngare, Bernadette Ng’eno, Inviolata Njeri, David Njogu, Bernard Obasi, Macdonald Obudho, Edwin Ochieng, Linus Odawo, Jacob Odhiambo, Caleb Ogada, Samuel Ogola, David Ojakaa, James Kwach Ojwang, George Okumu, Patricia Oluoch, Tom Oluoch, Kenneth Ochieng Omondi, Osborn Otieno, Yakubu Owolabi, Bharat Parekh, George Rutherford, Sandra Schwarcz, Shanaaz Sharrif, Victor Ssempijja, Yuko Takanaka, Mamo Umuro, Brian Eugene Wakhutu, Wanjiru Waruiru, Celia Wandera, John Wanyungu, Paul Waweru, Larry Westerman, Anthony Waruru, and Kelly Winter.

KAIS 2012 was supported by the National AIDS and STI Control Programme (NASCOP), Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS), National Public Health Laboratory Services (NPHLS), National AIDS Control Council (NACC), National Council for Population and Development (NCPD), Kenya Medical Research Institute, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC/Kenya, CDC/Atlanta), United States Agency for International Development (USAID/Kenya), University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), Joint United Nations Team on HIV/AIDS, Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation (EGPAF), Liverpool Voluntary Counselling and Testing (LVCT), African Medical and Research Foundation (AMREF), World Bank, and Global Fund. This publication was made possible by support from the US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief through cooperative agreements (#PS001805, GH000069, and PS001814) from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Global HIV/AIDS. This work was also funded in part by support from the Global Fund, World Bank, and the Joint United Nations Team for HIV/AIDS.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

The findings and conclusions in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Government of Kenya.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lucas SB, Hounnou A, Peacock C, et al. The mortality and pathology of HIV infection in a west African city. AIDS. 1993;7:1569–1579. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199312000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization (WHO) Global Tuberculosis Report 2012. WHO; Geneva, Switzerland: 2012. Available at: http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/gtbr12_main.pdf. Accessed June 20, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corbett EL, Marston B, Churchyard GJ, et al. Tuberculosis in subSaharan Africa: opportunities, challenges, and change in the era of anti-retroviral treatment. Lancet. 2006;367:926–937. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68383-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization (WHO) Consolidated Guidelines on the Use of Antiretroviral Drugs for Treating and Preventing HIV Infection: Recommendations for a Public Health Approach. WHO; Geneva, Switzerland: 2013. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/85321/1/9789241505727_eng.pdf. Accessed September 4, 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization (WHO) WHO Policy on Collaborative TB/HIV Activities Guidelines for National Programmes and Other Stake-holders. WHO; Geneva, Switzerland: 2013. Available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2012/9789241503006_eng.pdf. Accessed September 4, 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National AIDS and STI Control Programme (NASCOP) 2007 Kenya AIDS Indicator Survey Final Report. NASCOP; Nairobi, Kenya: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation (MOPHS) Division of Leprosy, Tuberculosis, and Lung Disease Annual Report, 2011. MOPHS; Nairobi, Kenya: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sitienei J, Kipruto H, Nganga L, et al. HIV testing and treatment among tuberculosis patients—Kenya, 2006-2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:1514–1517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waruiru W, Kim AA, Kimanga DO, et al. The Kenya AIDS indicator Survey 2012: rationale, methods, description of participants, and response rates. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;66(suppl 1):S3–S12. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National AIDS and STI Control Programme (NASCOP) Guidelines for Antiretroviral Therapy in Kenya. 4th NASCOP; Nairobi, Kenya: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 11.National AIDS and STI Control Programme (NASCOP) Kenya AIDS Indicator Survey 2012: Preliminary Report. NASCOP; Nairobi, Kenya: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Libamba E, Makombe S, Harries AD, et al. Scaling up antiretroviral therapy in Africa: learning from tuberculosis control programmes—the case of Malawi. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2005;9:1062–1071. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Odhiambo J, Kellogg TA, Kim AA, et al. Antiretroviral treatment scale-up among persons living with HIV in Kenya: results from a nationally representative survey. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;66(suppl 1):S116–S122. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National AIDS Control Council (NACC) Kenya AIDS Epidemic: Update 2011. NACC; Nairobi, Kenya: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dalal W, Feikin DR, Amolloh M, et al. Home-based HIV testing and counseling in rural and urban Kenyan communities. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;66(suppl 1):S116–S122. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318276bea0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams BG, Granich R, De Cock KM, et al. Antiretroviral therapy for tuberculosis control in nine African countries. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:19485–19489. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005660107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suthar AB, Lawn SD, del Amo J, et al. Antiretroviral therapy for prevention of tuberculosis in adults with HIV: a systematic review and metaanalysis. PLoS Med. 2012;9:e1001270. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tanser F, Bärnighausen T, Grapsa E, et al. High coverage of ART associated with decline in risk of HIV acquisition in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Science. 2013;339:966–971. doi: 10.1126/science.1228160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bor J, Herbst AJ, Newell M-L, et al. Increases in adult life expectancy in rural South Africa: valuing the scale-up of HIV treatment. Science. 2013;339:961–965. doi: 10.1126/science.1230413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Cock KM, Bunnell R, Mermin J. Unfinished business—expanding HIV testing in developing countries. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:440–442. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp058327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.De Cock KM, Marum E, Mbori-Ngacha D. A serostatus-based approach to HIV/AIDS prevention and care in Africa. Lancet. 2003;362:1847–2184. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14906-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]