Although no reliable estimate of adherence to oral antineoplastic therapies can be gleaned from the literature, a substantial proportion of patients struggle to adhere to these medications as prescribed. The few intervention studies for adherence have notable methodological concerns, thereby limiting the evidence to guide practice in promoting medication adherence among patients with cancer.

Keywords: Patient adherence, Medication adherence, Oral drug administration, Antineoplastic agents, Chemotherapy, Endocrine therapy

Abstract

Background.

Oral antineoplastic therapies not only improve survival but also reduce the burden of care for patients. Yet patients and clinicians face new challenges in managing adherence to these oral therapies. We conducted a systematic literature review to assess rates and correlates of adherence to oral antineoplastic therapies and interventions aimed at improving adherence.

Methods.

Following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines, we conducted a comprehensive literature search of the Ovid MEDLINE database from January 1, 2003 to June 30, 2015, using relevant terminology for oral antineoplastic agents. We included observational, database, and intervention studies. At least two researchers evaluated each paper to ensure accuracy of results and determine risk of bias.

Results.

We identified 927 records from the search and screened 214 abstracts. After conducting a full-text review of 167 papers, we included in the final sample 51 papers on rates/correlates of adherence to oral antineoplastic therapy and 12 papers on intervention studies to improve adherence. Rates of adherence varied widely, from 46% to 100%, depending on patient sample, medication type, follow-up period, assessment measure, and calculation of adherence. Of the intervention studies, only 1 of the randomized trials and 2 of the cohort studies showed benefit regarding adherence, with the majority suffering high risk of bias.

Conclusions.

Although no reliable estimate of adherence to oral antineoplastic therapies can be gleaned from the literature, a substantial proportion of patients struggle to adhere to these medications as prescribed. The few intervention studies for adherence have notable methodological concerns, thereby limiting the evidence to guide practice in promoting medication adherence among patients with cancer.

Implications for Practice:

Given the tremendous growth and development of oral antineoplastic therapies in the last decade, significant gaps have emerged in oncology practice with respect to standardized procedures for safe administration, monitoring, and management of these medications. Although rates of adherence to oral antineoplastic therapies vary widely depending on population, cancer type, and method of measurement, a substantial proportion of patients struggle to take their oral antineoplastic medications as prescribed. On the basis of current evidence and national recommendations, oncology practices should develop standard procedures for educating patients, reviewing and documenting treatment plans, and routinely monitoring patient adherence to oral antineoplastic therapies.

Introduction

During the last two decades, oral antineoplastic agents have increasingly become a primary form of treatment for many cancers, ranging from traditional endocrine and cytotoxic therapies to formulations targeting genetic mutations [1, 2]. Advances in oral therapies have not only improved outcomes and survival in patients with cancer but also have reduced the burden of care by allowing for convenient dosing outside of the hospital without the need for nurse administration and intravenous infusion [3]. Nonetheless, with these notable advantages comes a host of challenges related to patient safety, monitoring of adverse effects, and medication adherence [4].

Treatment adherence implies a collaborative approach to decision-making, ideally with mutual agreement between patient and clinician with respect to medication choice, dosing, and frequency of administration. We differentiate adherence from compliance, which connotes a passive role for patients in receiving and following medical advice, and from persistence, which refers to the duration of time from starting to stopping therapy [5]. Across disease states, studies show that approximately 50% of patients do not take their medications as prescribed [6]. Reasons for nonadherence vary and include patient (e.g., age, medication beliefs), provider (e.g., training, communication skills), treatment (e.g., multiple doses, adverse effects), and health care system (e.g., limited insurance coverage; lack of access to care) factors [7].

Within the context of cancer care, adherence to medications has become a high priority given the development of new oral therapies in recent years and accumulating evidence demonstrating poor adherence to these medications [8]. Most prior investigations have focused on adherence to oral endocrine therapy for breast cancer and medications for hematologic malignancies (namely chronic myeloid leukemia). Published reviews reveal quite variable, and sometimes alarmingly low, rates of adherence to these medications, even as low as 16% [9–12]. Moreover, studies show statistically significant associations between medication nonadherence and clinical and utilization outcomes, including cancer progression, more inpatient days, higher total health care spending, and worse survival [13–18].

Unfortunately, many oncology practices have not established standard protocols and documentation procedures for prescribing oral antineoplastic agents, educating patients about how to take these medications appropriately, monitoring for symptoms and adverse effects, or tracking adherence over time [19, 20]. A study in our institution revealed significantly lower rates of clinician documentation of discussions regarding treatment plans for oral chemotherapy relative to intravenous chemotherapy, per measures outlined in the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Quality Oncology Practice Initiative [21]. To help address this gap throughout the U.S., the Oncology Nursing Society and ASCO have published guidelines to improve standardization of practices to ensure patient safety, prescribing, and monitoring of oral chemotherapy, including medication adherence [22].

For the present systematic review, we evaluated studies on the rates and correlates of adherence to oral antineoplastic agents, including endocrine, cytotoxic, and targeted therapies across cancer types. In addition, we examined intervention studies aimed at improving adherence to oral chemotherapy. Finally, we discuss the implications of these findings for clinical practice and strategies to promote optimal medication adherence in patients with cancer.

Methods

Literature Search Strategy

We conducted a systematic review according to the guidelines for interventional and observational studies recommended by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [23]. To identify relevant studies, we used the following search terms: “adherence,” “compliance,” “malignancies,” “cancer,” “oncology,” “oral chemotherapy,” and “endocrine therapy.” In addition, the study team generated a comprehensive list of the names of oral antineoplastic agents to use as search terms (see supplemental online Appendix 1: Search Strategy). The list of agents was cross-checked by two oncologists and through the Micromedex website (Truven Health Analytics, Ann Arbor, MI, http://truvenhealth.com). The Micromedex website provides consumer information about commonly prescribed medications. An experienced research librarian conducted the preliminary search through Ovid MEDLINE from January 1, 2003 through June 30, 2015, including only studies written in English. Two independent researchers searched the bibliographies of the included studies for additional studies that met inclusion criteria.

Eligibility

In the review, we included studies that addressed rates, or rates and correlates, of adherence to oral antineoplastic agents, as well as interventional studies that aimed to improve medication adherence, in samples of adult participants (age >18 years) diagnosed with cancer. Adherence was defined as taking medication as prescribed with regard to daily amount, dosage, and frequency [5]. Eligible studies had to report a specific measure of adherence per the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcome Research, and we excluded those that used only nonspecific parameters for measuring adherence (e.g., discontinuation, persistence, gaps in treatment) [5].

Search Strategy and Extraction

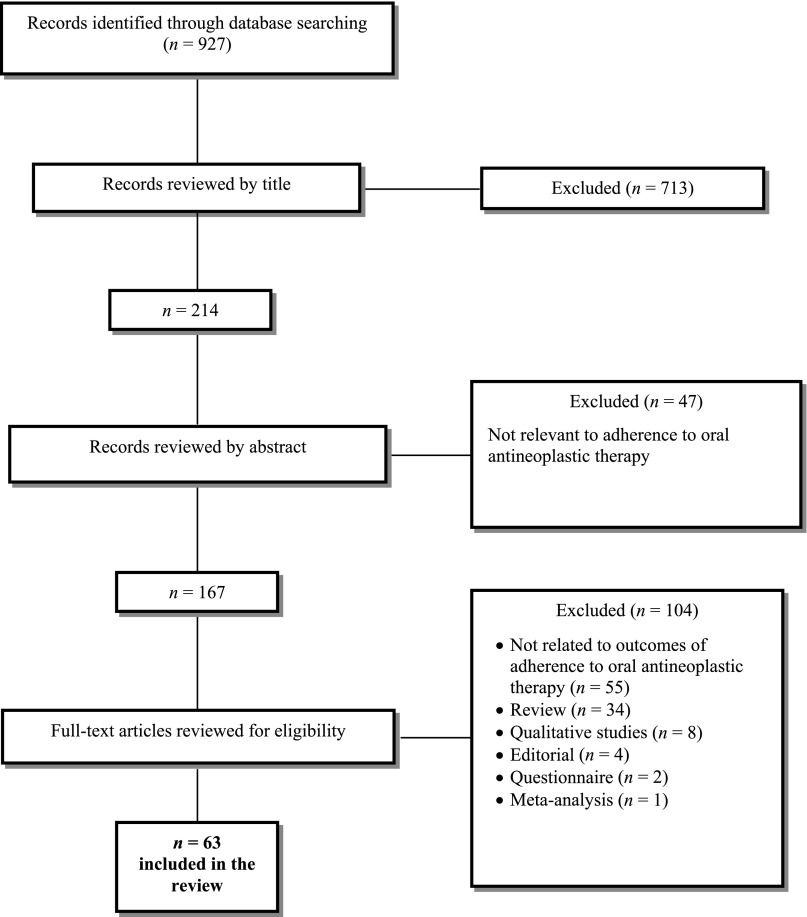

The study team conducted a multistep process to determine the final sample of papers to include in the review. Specifically, at least two independent study staff first screened all titles included in the initial search results, then reviewed the paper abstracts, and finally read through full versions of the papers to determine eligibility. The research team discussed and resolved any discrepancies in the screening process. Figure 1 displays the flowchart for identification of studies included in the review.

Figure 1.

Flowchart for selection of studies for inclusion in the systematic review.

After identifying eligible studies, we extracted the following data: treatment (oral endocrine or nonendocrine antineoplastic therapy), authors, year, patient sample, study design, method for measuring adherence, definition of adherence, intervention description (for intervention studies only), primary outcomes, adherence rates, and correlates of adherence. Research team members contacted authors if we observed errors in the reporting of results. All adherence rates reported in the studies were stated as percentages.

Assessment of Methodological Quality

We used several parameters to assess the methodological quality of studies, including the Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool to evaluate intervention studies [24]. To assess cohort and retrospective studies, we adapted a checklist of criteria [25] specific to cross-sectional, observational, and cohort studies used previously in cancer research [26], with additional evaluation criteria based on the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology statement [27].

The articles were split among five members of the research team. For each article, two research team members independently reviewed and rated the study for risk of bias in the methods and results (as low, moderate, or high) using the domains of the aforementioned assessment tools. The domains for the Cochrane risk of bias tool addressed random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other sources of bias. For observational and retrospective studies, evaluation criteria addressed the target population, transparency in planned or post hoc aims, sampling methods, specification of inclusion criteria, clear definitions for outcomes and predictors, use of validated instruments for measurement, adequate sample size, information about participants, adequacy of response rate, information on nonresponders or excluded cases, reporting of confidence intervals or standard errors, efforts to reduce potential bias, and specification of the funding source. The research team again discussed any discrepancies in risk of bias ratings until agreement was reached on all studies.

Results

Study Selection and Characteristics

In total, the research team screened 927 abstracts, of which 713 were excluded by title (Fig. 1). Next, the full abstract review included 214 articles, with 47 articles excluded at this step. The research team then reviewed the full text of the remaining 167 articles. Of the 104 articles excluded by full text, 55 articles were not related to outcomes of adherence to oral antineoplastic therapy or reported only on correlates of adherence, and we excluded the remaining because they were review articles (n = 34), qualitative studies (n = 8), editorials (n = 4), questionnaires (n = 2), or a meta-analysis (n = 1). Ultimately, 63 articles were included in the review: 51 studies pertaining to rates and correlates of adherence to oral antineoplastic therapies and 12 studies pertaining to interventions aimed at improving medication adherence in patients with cancer.

Assessment of Adherence

As shown in Tables 1–3, the measurement of adherence varied across studies (e.g., plasma drug level, electronic monitoring system, pharmacy records, medication tablet count, medical chart review, self-report or other report). We describe the measures of adherence below in order from most direct and objective to more indirect and subjective.

Plasma drug level: Only one (1.6%) study used a blood test to measure medication adherence. Investigators examined anastrozole plasma concentrations to determine the presence of the aromatase inhibitor in the blood [28].

Electronic monitoring devices: Devices (e.g., Medication Event Monitoring Systems [MEMS]) were used in seven (11.1%) studies to monitor medication adherence. Such devices typically use mobile technologies and embedded microprocessors to assess remotely patient adherence to oral medications by recording the date and time when a medication dispenser is opened.

Pharmacy and insurance records: Pharmacy and insurance databases were used in 32 (50.8%) studies to collect information about patients’ use of prescription medications. The databases generally include information regarding diagnoses, medical procedures, prescription claims, and when prescriptions had been filled (for new or refilled medications). The medication possession ratio (MPR) was most commonly used (n = 26 [41.3%]) to determine rate of adherence with access to pharmacy and insurance records. MPR is broadly defined as the percentage of days’ supply divided by a period of time. Although the period of time varied across studies, most assessed MPR for 1 year. Most commonly, adherence to the medication regimen of 80% or less indicated poor or low adherence in these studies.

Pill count: In five (7.9%) studies, pill counts were used to assess adherence. For these studies, patients brought their pill bottles to medical appointments, at which time investigators subtracted the number of pills remaining in the bottle from the number of pills prescribed. The percentage of adherence was based on how many pills should be left over (e.g., with perfect adherence, how many would be left on day X of the prescription) versus how many are left over (e.g., how many pills were actually still in the bottle on day X).

Medical chart review: Chart review was used in three (4.8%) studies. Typically, investigators reviewed medical charts to determine whether there was agreement between prescription and use of the oral agent during a period of time (e.g., 1 year).

Patient self-report: Self-report was used in 25 (39.7%) studies, and methods of self-report varied across studies. Typical self-report measures included, but were not limited to, validated assessments of adherence, such as the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS), the Medication Adherence Report Scale, and the visual analog rating scale (VAS). Other methods of self-report included items designed by the research team and calendar or diary entry.

Physician report: Physician report was used in seven (11.1%) of the studies and again varied in methodology. Physician report tools ranged from validated assessments (e.g., VAS, Basel Assessment of Adherence Scale [BAAS]) to nonvalidated items asking the physician to rate the patient as adherent/nonadherent.

Caregiver/family member report: In three (4.8%) studies, a caregiver or family member reported on patient medication adherence. For these studies, investigators used validated assessments of adherence such as the VAS and BAAS.

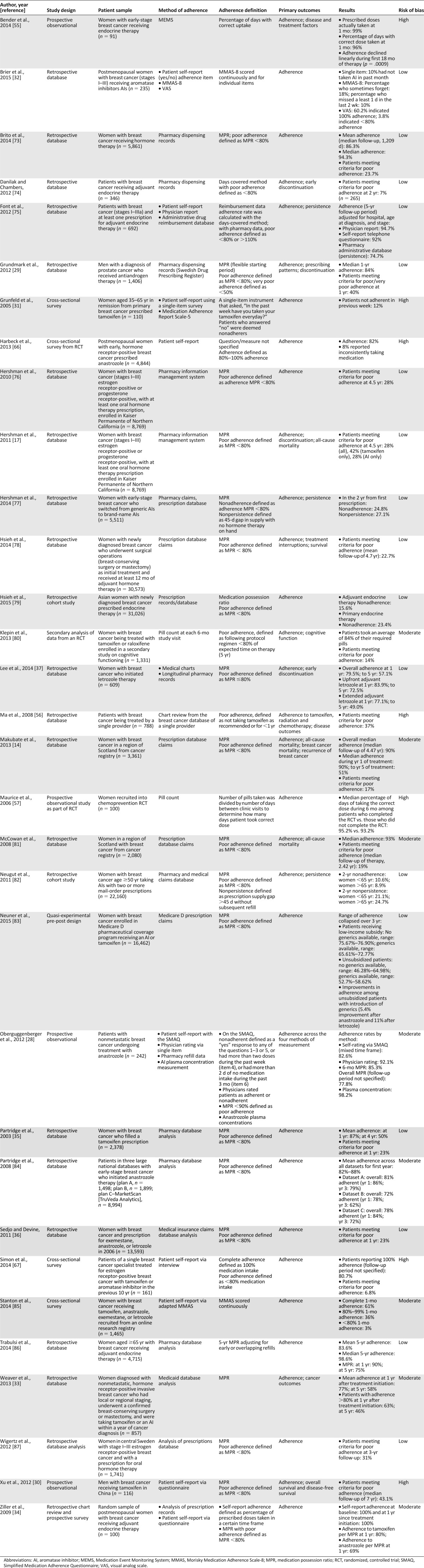

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies on rates of adherence to oral endocrine therapies

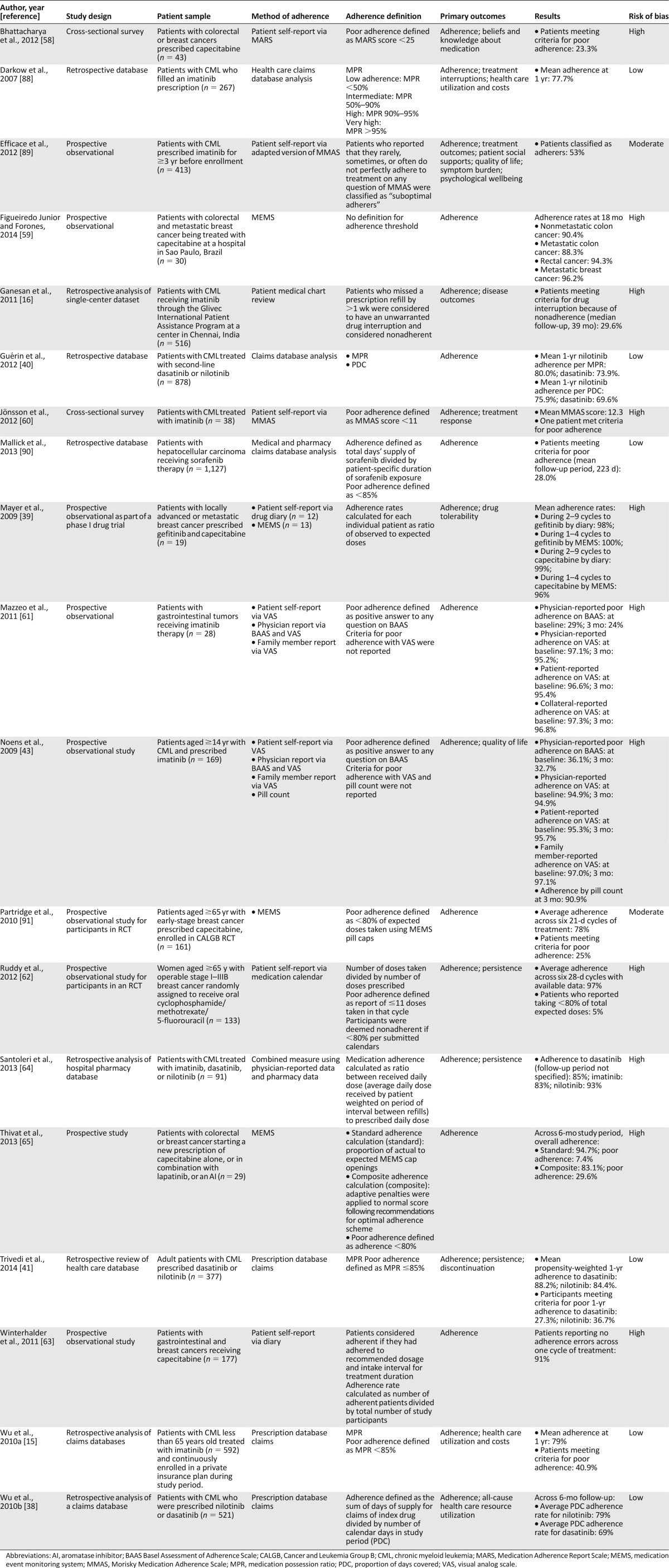

Table 3.

Characteristics of studies on rates of adherence to oral nonendocrine antineoplastic therapies

Rates of Adherence to Oral Antineoplastic Therapies

As shown in Table 1, we included 32 studies of adherence to oral endocrine therapy for cancer in the review. Of these, 30 (93.8%) primarily sampled women with breast cancer, whereas 2 exclusively included men with prostate cancer [29] (n = 1 [3.1%]) or breast cancer [30] (n = 1 [3.1%]). Across studies, investigators reported rates of adherence over a range of time points (from 1 week to 5 years) and as an average adherence percentage score (mean or median) for the entire sample or as a proportion of patients meeting a designated threshold for poor adherence (most commonly defined as <80% adherence). For example, in oral endocrine studies with follow-up time points less than 1 year, the proportion of patients with poor adherence varied from 12% at 1 week [31] to 10% at 1 month [32] to 14.7% at 6 months [28] in samples of patients with breast cancer. For the 1-year time point, average rates of adherence to endocrine therapy ranged from 77% [33] to 100% [34], with 23% [35, 36] to 40% [29] of patients meeting criteria for poor adherence according to a particular threshold (i.e., medication possession ratio <80%). Longitudinal investigations show that rates of adherence to oral endocrine therapy generally decline over time, with some studies showing rates dropping to approximately 50% adherence by 5-year follow-up [14, 33, 35, 37].

Also shown in Table 3, a total of 19 studies addressed rates of adherence to oral nonendocrine antineoplastic therapies in samples of patients with various cancer types: 47.4% (n = 9) chronic myeloid leukemia, 26.3% (n = 5) mixed cancers, 15.8% (n = 3) breast cancer, 5.3% (n = 1) hepatocellular carcinoma, and 5.3% (n = 1) gastrointestinal cancer. For this group of studies, average rates of adherence ranged from a low of 69% [38] to 100% [39] across a 6-month time period and from 69.6% [40] to 88.2% [41] at 1 year. Threshold scores indicated that as much as 20.5% [42] of patients (per MEMS) and 36.1% [43] of patients (per physician report) met criteria for poor adherence at baseline assessment. At 1 year, the proportion of patients meeting criteria for poor adherence per medication possession ratio (<85%) was also high, ranging from 27.3% [41] to 40.9% [15] across studies.

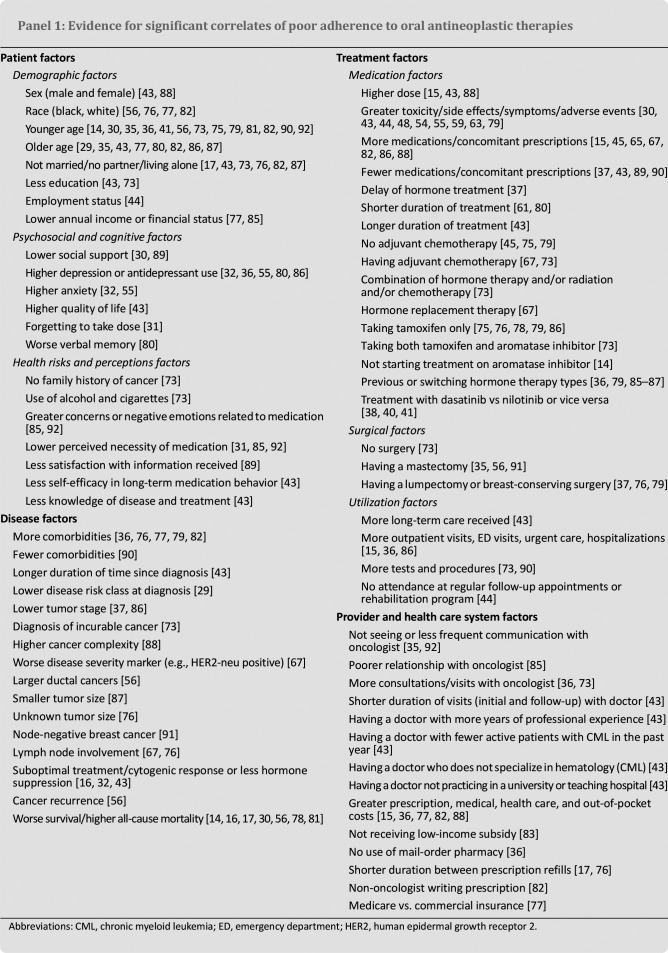

Correlates of Adherence to Oral Antineoplastic Therapies

Panel 1 lists the factors with evidence supporting an association with poor adherence to both oral endocrine and nonendocrine antineoplastic therapies. Specifically, investigators have identified several correlates of nonadherence, including patient, disease, treatment, and provider/health care system factors. With respect to patient factors, common correlates of poor adherence, across at least several studies, included patient age (i.e., both younger and older age), marital status (i.e., not being married), higher depression, and lower perceived need for the medication. Although disease correlates, such as the number of comorbidities, cancer stage, and nodal involvement, were mixed across studies, poor adherence to oral antineoplastic therapy was consistently associated with worse disease outcomes, including lower likelihood of response to therapy and higher mortality. Also, treatment factors, such as higher doses of medication, worse side effects, switching hormone therapy types, and higher utilization of medical care were associated with poor adherence. However, studies were less consistent in the direction of the relationship between adherence and the number of medications prescribed or surgery for cancer. Finally, fewer investigations included assessments of provider/health care system factors but existing data suggest that poor adherence to oral antineoplastic therapies is related to greater overall medical and out-of-pocket costs. Of note, Panel 1 only includes significant findings from studies examining correlates of adherence, given the difficulty of interpreting and lack of standard reporting among studies on nonsignificant associations.

Although disease correlates, such as the number of comorbidities, cancer stage, and nodal involvement, were mixed across studies, poor adherence to oral antineoplastic therapy was consistently associated with worse disease outcomes, including lower likelihood of response to therapy and higher mortality.

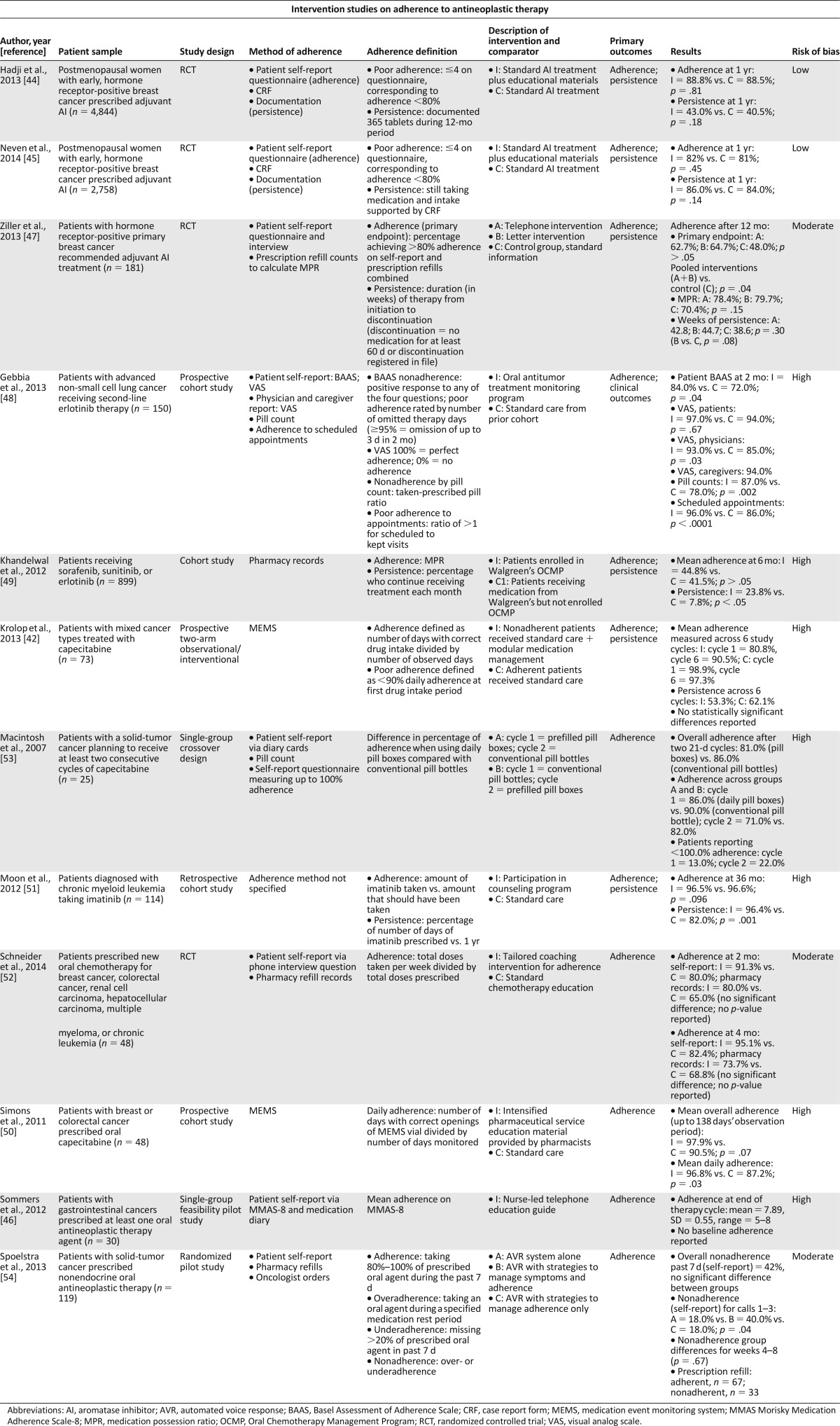

Interventions to Improve Adherence to Oral Antineoplastic Therapies

In a total of 12 studies (Table 2), investigators assessed interventions to improve adherence to oral antineoplastic therapies for patients with various malignancies, including mixed cancer types (n = 6 [50.0%]), breast cancer (n = 3 [25.0%]), non-small cell lung cancer (n = 1 [8.3%]), gastrointestinal cancer (n = 1 [8.3%]), and chronic myeloid leukemia (n = 1 [8.3%]). Interventions varied in format, such as educational support [44–47], treatment monitoring [48], pharmacy-based programs [42, 49, 50], counseling programs [51, 52], prefilled pill boxes [53], and automated voice response systems [54]. Five of these studies were randomized trials, none of which demonstrated significant differences between the intervention and control groups with respect to their primary adherence outcomes [44, 45, 47, 52, 54]. One randomized, three-arm trial did show differences in adherence, favoring the intervention groups, when the investigators conducted a post hoc pooled analysis comparing both interventions to the control group [47].

Table 2.

Studies of interventions for adherence to oral antineoplastic therapies

The remaining investigations included two single-group studies (i.e., a feasibility pilot study [46] and a randomized crossover study [53]) and five investigations of nonrandomized observational cohorts with control groups [42, 48–51]. Of these investigations, only two nonrandomized cohort studies showed a significant benefit of their respective interventions for adherence to oral antineoplastic therapy relative to their control groups. In one of the cohort studies, Gebbia et al. [48] showed that a treatment monitoring program for patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer was associated with significantly higher rates of adherence to second-line erlotinib (as measured by both patient self-report [p = .042] and pill count [p = .002]) and disease control (p = .037) relative to a retrospective standard care control group. Finally, Simons et al. [50] showed that intensified multidisciplinary pharmaceutical care was associated with significantly higher mean daily adherence rates to oral capecitabine in a small cohort of patients with colorectal and breast cancer compared with a control group that received standard care (p = .029). However, overall adherence for the observational period in this study was only marginally significantly different between cohorts (p = .069).

Evaluation of Study Quality and Risk of Bias

Using standardized methods for evaluation of study quality [24, 25, 27], the research team judged 18 of 51 (35.3%) of the studies pertaining to rates and correlates of adherence to oral antineoplastic therapy to be high risk of bias, as noted in Tables 1 and 3. The most common factors that contributed to high risk of bias ratings included poor specification of target population and convenience sampling methods [16, 39, 43, 55–63], small sample sizes [39, 58–61, 64, 65], lack of clear description of outcomes and/or inadequate measurement of adherence [16, 31, 39, 56, 66, 67], and low response rate and/or lack of information on nonresponders [30, 31, 39, 43, 55, 57–63, 65–67], among other factors (supplemental online Appendix 2 provides full criteria and ratings). As shown in Table 2, the research team rated the majority of the intervention studies (58.3% [n = 7 of 12]) to have high risk of bias, primarily because of use of single-group and nonrandomized study designs [42, 46, 48–51, 53], lack of power analyses, and/or small samples sizes [42, 46, 48, 49, 51, 53], as well as missing outcome data [42, 46, 48–51, 53], among other factors (supplemental online Appendix 3 provides full criteria and ratings). The remainder of the studies on rates and correlates of adherence (64.7% [n = 33 of 51]) and on interventions to improve medication adherence (41.7% [n = 5 of 12]) were judged to have moderate to low risk of bias.

Discussion

Overview of Findings

In this systematic review of the literature dating from January 2003 through June 2015, 32 studies assessed rates and correlates of adherence to oral endocrine therapy, whereas 19 studies focused on nonendocrine antineoplastic agents (primarily oral agents for chronic myeloid leukemia). Adherence estimates ranged widely across studies from 46% to 100% [33, 39]. Reasons for this variation are complex but largely due to the diverse methods for assessing medication adherence, lack of standardization in defining optimal adherence, considerable differences in length of study follow-up periods, and poor methodological quality of studies. Nonetheless, the findings show that indirect methods, such as self-report, tend to yield higher estimates of medication adherence as compared with calculations based on pharmacy data (i.e., medication possession ratios) or electronic medication event monitoring systems. Remarkably, only one study used direct biological methods (i.e., plasma concentration) for the adherence measurement. The results further suggest that adherence to oral antineoplastic therapy declines significantly over time. Factors associated with poor medication adherence varied across cancer types and related to many salient patient, disease, treatment, and provider/health care system factors. Few predictors of adherence to oral antineoplastic therapies were reliable and significant across studies, making definitive conclusions difficult to draw. These findings are consistent with those of prior reviews of adherence to oral antineoplastic therapy [8–10].

Twelve intervention studies were also included in this systematic review, most of which suffered high risk of bias due to nonrandomized designs, small sample sizes, subjective assessments of adherence, and missing data concerns. Only one of the randomized controlled trials demonstrated an effect on adherence to oral antineoplastic therapy, on the basis of a post hoc analysis that pooled the intervention groups [47]; two cohort studies showed preliminary evidence for the benefit of a treatment monitoring program and multidisciplinary pharmaceutical care [48, 50]. The primary outcome in most intervention studies was self-reported adherence, with only two studies using more objective MEMS data as the adherence measure [42, 50]. Further work is clearly needed using methodologically rigorous, prospective randomized designs in larger samples of patients that assess not only adherence with multiple methods but also clinically meaningful outcomes, such as quality of life, symptoms, and adverse effects of therapy, as well as cancer progression and survival. In the other systematic review of interventions to promote adherence to oral antineoplastic that has been published to date, the investigators drew similar conclusions [68].

The current review has many strengths related to use of PRISMA-based methods to ensure a rigorous evaluation of studies regarding adherence to oral antineoplastic therapy across a range of cancer types and included endocrine and nonendocrine medications. Although several reviews of adherence to oral antineoplastic therapies have been published [8, 12, 69, 70], only a few were based on the systematic reporting criteria per PRISMA guidelines [10, 11, 68]. Furthermore, we examined observational, retrospective database, cohort, and randomized intervention studies to describe not only rates and correlates of adherence but also empirical efforts to date to improve proper administration of these oral agents. Yet, we did limit the search time frame to January 2003 through June 2015 and therefore did not include studies published before that time. Despite this limitation, we can still glean salient clinical implications from the extant literature to help guide current practice.

Clinical Considerations

To date, no clinically defined critical threshold for medication adherence to oral antineoplastic therapies exists. Besides direct biological assessments, all indirect methods have potential limitations that are due to self-report biases or to lack of precision in determining the exact time a medication dose was taken. Although MEMS offers an advantage in this regard because a microprocessor records the date and time a medication bottle was opened, it is an expensive instrument that still fails to ascertain whether a patient actually took the medication. Even with the problems of indirect measurement, oncology clinicians should nonetheless integrate validated assessments of medication adherence into routine clinical practice at every clinic visit. Even single-item questions, such as “How well have you been taking your medications as prescribed during the past week?” (very poor to excellent) or “What percentage of the time did you take your medication as prescribed over the past week?” (0%–100%), correlate fairly well with medication event monitoring systems. Asking patients about adherence in the affirmative, as previously described, rather than the negative (e.g., “How many doses did you miss in the last week?”) may yield more reliable and accurate responses [71].

After a clinician identifies a patient experiencing problems with medication adherence, a follow-up evaluation of the diverse and often complex contributing factors will help guide recommendations to improve the patient’s medication-taking behaviors. Such interventions will probably vary according to the individual needs of patients as well as the type of medication. Clinicians can work with their patients to help clarify and problem-solve the use of reminder systems, management of untoward side effects, misconceptions regarding the severity of the disease or potential efficacy of the medication, instructions for the amount and timing of dosing, and strategies for overcoming any system barriers to accessing or paying for the medication. As with patients who have other chronic medical conditions, limited social support and depression symptoms may also be common and complicating factors negatively affecting medication adherence. For such individuals, referral for evidence-based cognitive-behavioral therapy that integrates interventions for mood and medication adherence may be useful [72].

As with patients who have other chronic medical conditions, limited social support and depression symptoms may also be common and complicating factors negatively affecting medication adherence.

In striving to adhere to national quality guidelines and recommendations for safe administration of oral chemotherapy, oncology practices may begin to develop standard protocols for prescribing oral antineoplastic therapies, educating and monitoring patients over time, and documenting these care practices. Given that the frequency of contact with onsite clinician consultations may be lower with oral medications than with infusion chemotherapy, much of the ongoing assessment of symptoms, adverse effects, and adherence will need to occur remotely, either electronically or telephonically. Researchers will want to develop and test novel models of care that not only promote safe administration and handling of these medications but also encourage routine evaluation of patients to ensure optimal adherence. For example, our team is testing the development and efficacy of a smartphone mobile application to enhance symptom monitoring and adherence to oral chemotherapy as part of a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute project (#IHS-1306-03616; principal investigator: J.A.G.). Some of the features of this application include a personalized treatment plan, at least weekly reporting of symptoms and adherence, patient-centered resources on behavioral strategies to cope with adverse effects, and real-time reports delivered to the oncology team on symptoms and medication adherence. If proven successful, remote monitoring programs for oral antineoplastic therapy such as this may be an important evidence-based adjunct to standard oncology care.

Conclusion

As the administration of cancer treatment increasingly moves from the hospital to the home, oncology care teams and their patients face new challenges in ensuring optimal adherence to therapy. Data suggest that rates of adherence to oral antineoplastic agents vary widely across cancers and methods of measurements but a substantial proportion of patients struggle to take their medications as prescribed, with adherence declining over time. Reasons for nonadherence cut across patient, disease, treatment, provider, and health care system factors, resulting in poorer clinical outcomes. Furthermore, the lack of data on effective strategies for promoting medication adherence in patients with cancer underscores the need for more research on comprehensive interventions and novel models of care to address this critical gap in oncology treatment.

See http://www.TheOncologist.com for supplemental material available online.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was supported by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (IHS-1306-03616, PI: Greer). PROSPERO registration number is CRD42014014785.

Footnotes

For Further Reading: Willemien van de Water, Esther Bastiaannet, Elysée T.M. Hille, et al. Age-Specific Nonpersistence of Endocrine Therapy in Postmenopausal Patients Diagnosed With Hormone Receptor–Positive Breast Cancer: A TEAM Study Analysis. The Oncologist 2012;17:55–63.

Abstract

Background. Early discontinuation of adjuvant endocrine therapy may affect the outcome of treatment in breast cancer patients. The aim of this study was to assess age-specific persistence and age-specific survival outcome based on persistence status.

Methods. Patients enrolled in the Tamoxifen Exemestane Adjuvant Multinational trial were included. Nonpersistence was defined as discontinuing the assigned endocrine treatment within 1 year of follow-up because of adverse events, intercurrent illness, patient refusal, or other reasons. Endpoints were the breast cancer–specific and overall survival times. Analyses were stratified by age at diagnosis (<65 years, 65–74 years, ≥75 years).

Results. Overall, 3,142 postmenopausal breast cancer patients were included: 1,682 were aged <65 years, 951 were aged 65–74 years, and 509 were aged ≥75 years. Older age was associated with a higher proportion of nonpersistence within 1 year of follow-up. In patients aged <65 years, nonpersistent patients had lower breast cancer–specific and overall survival probabilities. In patients aged 65–74 years and patients aged ≥75 years, the survival times of persistent and nonpersistent patients were similar.

Conclusion. Nonpersistence within 1 year of follow-up was associated with lower breast cancer–specific and overall survival probabilities in patients aged <65 years, but it was not associated with survival outcomes in patients aged 65–74 years or in patients aged ≥75 years. These results suggest that extrapolation of outcomes from a young to an elderly breast cancer population may be insufficient and urge age-specific breast cancer studies.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Joseph A. Greer, Nicole Amoyal, Inga Lennes, Jennifer S. Temel, Steven A. Safren, William F. Pirl

Provision of study material or patients: Joseph A. Greer, Nicole Amoyal, Lauren Nisotel, Joel N. Fishbein, James MacDonald, Jamie Stagl

Collection or assembly of data: Joseph A. Greer, Nicole Amoyal, Lauren Nisotel, Joel N. Fishbein, James MacDonald, Jamie Stagl

Data analysis and interpretation: Joseph A. Greer, Nicole Amoyal, Lauren Nisotel, Joel N. Fishbein, James MacDonald, Jamie Stagl, Inga Lennes, Jennifer S. Temel, Steven A. Safren, William F. Pirl

Manuscript writing: Joseph A. Greer, Nicole Amoyal, Jamie Stagl, Jennifer S. Temel, Steven A. Safren, William F. Pirl

Final approval of manuscript: Joseph A. Greer, Nicole Amoyal, Lauren Nisotel, Joel N. Fishbein, James MacDonald, Jamie Stagl, Inga Lennes, Jennifer S. Temel, Steven A. Safren, William F. Pirl

Disclosures

Jennifer S. Temel: Helsinn Therapeutics (travel funds). The other authors indicated no financial relationships.

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (ET) Expert testimony; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

References

- 1.O’Neill VJ, Twelves CJ. Oral cancer treatment: Developments in chemotherapy and beyond. Br J Cancer. 2002;87:933–937. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Findlay M, von Minckwitz G, Wardley A. Effective oral chemotherapy for breast cancer: pillars of strength. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:212–222. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borner M, Scheithauer W, Twelves C, et al. Answering patients’ needs: Oral alternatives to intravenous therapy. The Oncologist. 2001;6(suppl 4):12–16. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.6-suppl_4-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weingart SN, Brown E, Bach PB, et al. NCCN Task Force Report: Oral chemotherapy. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2008;6(suppl 3):S1–S14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cramer JA, Roy A, Burrell A, et al. Medication compliance and persistence: terminology and definitions. Value Health. 2008;11:44–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. World Health Organization. Adherence to long-term therapies: Evidence for action. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2003.

- 7.Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:487–497. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruddy K, Mayer E, Partridge A. Patient adherence and persistence with oral anticancer treatment. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:56–66. doi: 10.3322/caac.20004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Partridge AH, Avorn J, Wang PS, et al. Adherence to therapy with oral antineoplastic agents. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:652–661. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.9.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mathes T, Pieper D, Antoine S L, et al. Adherence influencing factors in patients taking oral anticancer agents: A systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol. 2014;38:214–226. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2014.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murphy CC, Bartholomew LK, Carpentier MY, et al. Adherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy among breast cancer survivors in clinical practice: A systematic review. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;134:459–478. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2114-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Barrak J, Cheung WY. Adherence to imatinib therapy in gastrointestinal stromal tumors and chronic myeloid leukemia. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21:2351–2357. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-1831-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Given BA, Spoelstra SL, Grant M. The challenges of oral agents as antineoplastic treatments. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2011;27:93–103. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Makubate B, Donnan PT, Dewar JA, et al. Cohort study of adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy, breast cancer recurrence and mortality. Br J Cancer. 2013;108:1515–1524. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu EQ, Johnson S, Beaulieu N, et al. Healthcare resource utilization and costs associated with non-adherence to imatinib treatment in chronic myeloid leukemia patients. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26:61–69. doi: 10.1185/03007990903396469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ganesan P, Sagar TG, Dubashi B, et al. Nonadherence to imatinib adversely affects event free survival in chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia. Am J Hematol. 2011;86:471–474. doi: 10.1002/ajh.22019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hershman DL, Shao T, Kushi LH, et al. Early discontinuation and non-adherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy are associated with increased mortality in women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;126:529–537. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1132-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCowan C, Wang S, Thompson AM, et al. The value of high adherence to tamoxifen in women with breast cancer: a community-based cohort study. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:1172–1180. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weingart SN, Flug J, Brouillard D, et al. Oral chemotherapy safety practices at US cancer centres: questionnaire survey. BMJ. 2007;334:407. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39069.489757.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weingart SN, Li JW, Zhu J, et al. US Cancer Center Implementation of ASCO/Oncology Nursing Society Chemotherapy Administration Safety Standards. J Oncol Pract. 2012;8:7–12. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greer JA, Lennes IT, Gallagher ER, et al. Documentation of oral versus intravenous chemotherapy plans in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10:e103–e106. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2013.001154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neuss MN, Polovich M, McNiff K, et al. 2013 updated American Society of Clinical Oncology/Oncology Nursing Society chemotherapy administration safety standards including standards for the safe administration and management of oral chemotherapy. J Oncol Pract. 2013;9(suppl):5s–13s. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2013.000874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:264–269, W64. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Higgins J, Green S. eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 5.1.0. 2011. Available at http://www.cochrane-handbook.org. Accessed March 24, 2015.

- 25.Radulescu M, Diepgen TL, Weisshaar E, et al. What makes a good prevalence survey. Evidence Based Dermatol. 2009;2:61–67. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dilworth S, Higgins I, Parker V, et al. Patient and health professional’s perceived barriers to the delivery of psychosocial care to adults with cancer: A systematic review. Psychooncology. 2014;23:601–612. doi: 10.1002/pon.3474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:573–577. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oberguggenberger AS, Sztankay M, Beer B, et al. Adherence evaluation of endocrine treatment in breast cancer: methodological aspects. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:474. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grundmark B, Garmo H, Zethelius B, et al. Anti-androgen prescribing patterns, patient treatment adherence and influencing factors; results from the nationwide PCBaSe Sweden. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;68:1619–1630. doi: 10.1007/s00228-012-1290-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu S, Yang YR, Tao W, et al. Tamoxifen adherence and its relationship to mortality in 116 men with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;136:495–502. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2286-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grunfeld EA, Hunter MS, Sikka P, et al. Adherence beliefs among breast cancer patients taking tamoxifen. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;59:97–102. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brier MJ, Chambless D, Gross R, et al. Association between self-report adherence measures and oestrogen suppression among breast cancer survivors on aromatase inhibitors. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51:1890–1896. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.06.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weaver KE, Camacho F, Hwang W, et al. Adherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy and its relationship to breast cancer recurrence and survival among low-income women. Am J Clin Oncol. 2013;36:181–187. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e3182436ec1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ziller V, Kalder M, Albert US, et al. Adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy in postmenopausal women with breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:431–436. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Partridge AH, Wang PS, Winer EP, et al. Nonadherence to adjuvant tamoxifen therapy in women with primary breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:602–606. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.07.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sedjo RL, Devine S. Predictors of non-adherence to aromatase inhibitors among commercially insured women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;125:191–200. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0952-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee HS, Lee JY, Ah YM, et al. Low adherence to upfront and extended adjuvant letrozole therapy among early breast cancer patients in a clinical practice setting. Oncology. 2014;86:340–349. doi: 10.1159/000360702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu EQ, Guerin A, Yu AP, et al. Retrospective real-world comparison of medical visits, costs, and adherence between nilotinib and dasatinib in chronic myeloid leukemia. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26:2861–2869. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2010.533648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mayer EL, Partridge AH, Harris LN, et al. Tolerability of and adherence to combination oral therapy with gefitinib and capecitabine in metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;117:615–623. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0366-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guérin A, Chen L, Wu EQ, et al. A retrospective analysis of therapy adherence in imatinib resistant or intolerant patients with chronic myeloid leukemia receiving nilotinib or dasatinib in a real-world setting. Curr Med Res Opin. 2012;28:1155–1162. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2012.705264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Trivedi D, Landsman-Blumberg P, Darkow T, et al. Adherence and persistence among chronic myeloid leukemia patients during second-line tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2014;20:1006–1015. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2014.20.10.1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krolop L, Ko YD, Schwindt PF, et al. Adherence management for patients with cancer taking capecitabine: A prospective two-arm cohort study. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e003139. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Noens L, van Lierde MA, De Bock R, et al. Prevalence, determinants, and outcomes of nonadherence to imatinib therapy in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia: The ADAGIO study. Blood. 2009;113:5401–5411. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-196543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hadji P, Blettner M, Harbeck N, et al. The Patient’s Anastrozole Compliance to Therapy (PACT) Program: A randomized, in-practice study on the impact of a standardized information program on persistence and compliance to adjuvant endocrine therapy in postmenopausal women with early breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:1505–1512. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Neven P, Markopoulos C, Tanner M, et al. The impact of educational materials on compliance and persistence rates with adjuvant aromatase inhibitor treatment: First-year results from the compliance of aromatase inhibitors assessment in daily practice through educational approach (CARIATIDE) study. Breast. 2014;23:393–399. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2014.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sommers RM, Miller K, Berry DL. Feasibility pilot on medication adherence and knowledge in ambulatory patients with gastrointestinal cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2012;39:E373–E379. doi: 10.1188/12.ONF.E373-E379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ziller V, Kyvernitakis I, Knöll D, et al. Influence of a patient information program on adherence and persistence with an aromatase inhibitor in breast cancer treatment--the COMPAS study. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:407. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gebbia V, Bellavia M, Banna GL, et al. Treatment monitoring program for implementation of adherence to second-line erlotinib for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer. 2013;14:390–398. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Khandelwal N, Duncan I, Ahmed T, et al. Oral chemotherapy program improves adherence and reduces medication wastage and hospital admissions. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2012;10:618–625. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2012.0063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Simons S, Ringsdorf S, Braun M, et al. Enhancing adherence to capecitabine chemotherapy by means of multidisciplinary pharmaceutical care. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19:1009–1018. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-0927-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moon JH, Sohn SK, Kim SN, et al. Patient counseling program to improve the compliance to imatinib in chronic myeloid leukemia patients. Med Oncol. 2012;29:1179–1185. doi: 10.1007/s12032-011-9926-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schneider SM, Adams DB, Gosselin T. A tailored nurse coaching intervention for oral chemotherapy adherence. J Adv Pract Oncol. 2014;5:163–172. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Macintosh PW, Pond GR, Pond BJ, et al. A comparison of patient adherence and preference of packaging method for oral anticancer agents using conventional pill bottles versus daily pill boxes. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2007;16:380–386. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2006.00758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Spoelstra SL, Given BA, Given CW, et al. An intervention to improve adherence and management of symptoms for patients prescribed oral chemotherapy agents: An exploratory study. Cancer Nurs. 2013;36:18–28. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3182551587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bender CM, Gentry AL, Brufsky AM, et al. Influence of patient and treatment factors on adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy in breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2014;41:274–285. doi: 10.1188/14.ONF.274-285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ma AM, Barone J, Wallis AE, et al. Noncompliance with adjuvant radiation, chemotherapy, or hormonal therapy in breast cancer patients. Am J Surg. 2008;196:500–504. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2008.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Maurice A, Howell A, Evans DG, et al. Predicting compliance in a breast cancer prevention trial. Breast J. 2006;12:446–450. doi: 10.1111/j.1075-122X.2006.00295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bhattacharya D, Easthall C, Willoughby KA, et al. Capecitabine non-adherence: Exploration of magnitude, nature and contributing factors. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2012;18:333–342. doi: 10.1177/1078155211436022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Figueiredo Junior AG, Forones NM. Study on adherence to capecitabine among patients with colorectal cancer and metastatic breast cancer. Arq Gastroenterol. 2014;51:186–191. doi: 10.1590/s0004-28032014000300004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jönsson S, Olsson B, Söderberg J, et al. Good adherence to imatinib therapy among patients with chronic myeloid leukemia--a single-center observational study. Ann Hematol. 2012;91:679–685. doi: 10.1007/s00277-011-1359-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mazzeo F, Duck L, Joosens E, et al. Nonadherence to imatinib treatment in patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors: The ADAGIO study. Anticancer Res. 2011;31:1407–1409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ruddy KJ, Pitcher BN, Archer LE, et al. Persistence, adherence, and toxicity with oral CMF in older women with early-stage breast cancer (Adherence Companion Study 60104 for CALGB 49907) Ann Oncol. 2012;23:3075–3081. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Winterhalder R, Hoesli P, Delmore G, et al. Self-reported compliance with capecitabine: Findings from a prospective cohort analysis. Oncology. 2011;80:29–33. doi: 10.1159/000328317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Santoleri F, Sorice P, Lasala R, et al. Patient adherence and persistence with imatinib, nilotinib, dasatinib in clinical practice. PLoS One. 2013;8:e56813. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Thivat E, Van Praagh I, Belliere A, et al. Adherence with oral oncologic treatment in cancer patients: Interest of an adherence score of all dosing errors. Oncology. 2013;84:67–74. doi: 10.1159/000342087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Harbeck N, Blettner M, Hadji P, et al. Patient’s Anastrozole Compliance to Therapy (PACT) Program: baseline data and patient characteristics from a population-based, randomized study evaluating compliance to aromatase inhibitor therapy in postmenopausal women with hormone-sensitive early breast cancer. Breast Care (Basel) 2013;8:110–120. doi: 10.1159/000350777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Simon R, Latreille J, Matte C, et al. Adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer patients with regular follow-up. Can J Surg. 2014;57:26–32. doi: 10.1503/cjs.006211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mathes T, Antoine SL, Pieper D, et al. Adherence enhancing interventions for oral anticancer agents: A systematic review. Cancer Treat Rev. 2014;40:102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Banning M. Adherence to adjuvant therapy in post-menopausal breast cancer patients: A review. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2012;21:10–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2011.01295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bassan F, Peter F, Houbre B, et al. Adherence to oral antineoplastic agents by cancer patients: definition and literature review. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2014;23:22–35. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Greer JA, Helmuth PJ, Gonzalez JS, et al. Nonadherence to treatment. In: Fogel B, Greenberg D, editors. Psychiatric Care of the Medical Patient. 3rd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2015. pp. 253–265. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Safren SA, Gonzalez JS, Soroudi N. Coping With Chronic Illness: A Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy Approach for Adherence and Depression. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Brito C, Portela MC, de Vasconcellos MT. Adherence to hormone therapy among women with breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:397. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Danilak M, Chambers CR. Adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy in women with breast cancer. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2013;19:105–110. doi: 10.1177/1078155212455939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Font R, Espinas JA, Gil-Gil M, et al. Prescription refill, patient self-report and physician report in assessing adherence to oral endocrine therapy in early breast cancer patients: A retrospective cohort study in Catalonia, Spain. Br J Cancer. 2012;107:1249–1256. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hershman DL, Kushi LH, Shao T, et al. Early discontinuation and nonadherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy in a cohort of 8,769 early-stage breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4120–4128. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.9655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hershman DL, Tsui J, Meyer J, et al. The change from brand-name to generic aromatase inhibitors and hormone therapy adherence for early-stage breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106:dju319. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hsieh KP, Chen LC, Cheung KL, et al. Interruption and non-adherence to long-term adjuvant hormone therapy is associated with adverse survival outcome of breast cancer women--an Asian population-based study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e87027. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hsieh KP, Chen LC, Cheung KL, et al. Risks of nonadherence to hormone therapy in Asian women with breast cancer. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2015;31:328–334. doi: 10.1016/j.kjms.2015.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Klepin HD, Geiger AM, Bandos H, et al. Cognitive factors associated with adherence to oral antiestrogen therapy: Results from the cognition in the study of tamoxifen and raloxifene (Co-STAR) study. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2014;7:161–168. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-13-0165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.McCowan C, Shearer J, Donnan PT, et al. Cohort study examining tamoxifen adherence and its relationship to mortality in women with breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2008;99:1763–1768. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Neugut AI, Subar M, Wilde ET, et al. Association between prescription co-payment amount and compliance with adjuvant hormonal therapy in women with early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2534–2542. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.3179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Neuner JM, Kamaraju S, Charlson JA, et al. The introduction of generic aromatase inhibitors and treatment adherence among Medicare D enrollees. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107 doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv130. djv130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Partridge AH, LaFountain A, Mayer E, et al. Adherence to initial adjuvant anastrozole therapy among women with early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:556–562. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.5451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Stanton AL, Petrie KJ, Partridge AH. Contributors to nonadherence and nonpersistence with endocrine therapy in breast cancer survivors recruited from an online research registry. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;145:525–534. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-2961-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Trabulsi N, Riedel K, Winslade N, et al. Adherence to anti-estrogen therapy in seniors with breast cancer: How well are we doing? Breast J. 2014;20:632–638. doi: 10.1111/tbj.12328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wigertz A, Ahlgren J, Holmqvist M, et al. Adherence and discontinuation of adjuvant hormonal therapy in breast cancer patients: A population-based study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;133:367–373. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-1961-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Darkow T, Henk HJ, Thomas SK, et al. Treatment interruptions and non-adherence with imatinib and associated healthcare costs: A retrospective analysis among managed care patients with chronic myelogenous leukaemia. Pharmacoeconomics. 2007;25:481–496. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200725060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Efficace F, Baccarani M, Rosti G, et al. Investigating factors associated with adherence behaviour in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia: An observational patient-centered outcome study. Br J Cancer. 2012;107:904–909. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mallick R, Cai J, Wogen J. Predictors of non-adherence to systemic oral therapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Curr Med Res Opin. 2013;29:1701–1708. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2013.842161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Partridge AH, Archer L, Kornblith AB, et al. Adherence and persistence with oral adjuvant chemotherapy in older women with early-stage breast cancer in CALGB 49907: Adherence companion study 60104. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2418–2422. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.4671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Jacob Arriola KR, Mason TA, Bannon KA, et al. Modifiable risk factors for adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy among breast cancer patients. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;95:98–103. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.