Abstract

Background

Previously, eighteen percent of childhood cancer patients who survived five years died within the subsequent 25 years. In recent decades, cancer treatment regimens have been modified with the goal of reducing risk for life-threatening late effects.

Methods

Late mortality was evaluated in 34,033 five-year survivors of childhood cancer (diagnosed <21 years of age from 1970-1999, median follow-up 21 years, range 5-38). Demographic and disease factors associated with mortality due to health-related causes, which exclude recurrence/progression of the original cancer but include deaths that reflect late effects of cancer therapy, were evaluated using cumulative incidence and piecewise exponential models estimating relative rates (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Results

1,618 (41%) of the 3,958 deaths were attributable to health-related causes, including 746 subsequent neoplasm, 241 cardiac, and 137 pulmonary deaths. Reduction in 15-year mortality was observed for all-cause (12.4% to 6.0%, P for trend <0.001) and health-related mortality (3.5% to 2.1%, P for trend <0.001), attributable to reductions in subsequent neoplasm (P<0.001), cardiac (P<0.001) and pulmonary death (P<0.001). Changes in therapy by decade included reduced rates of: cranial radiotherapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (1970s 85%, 1980s 51%, 1990s 19%), abdominal radiotherapy for Wilms’ tumor (78%, 53%, 43%), chest radiotherapy for Hodgkin's lymphoma (87%, 79%, 61%), and anthracycline exposure. Reduction in treatment exposure was associated with reduced late mortality among lymphoblastic leukemia and Wilms’ tumor survivors.

Conclusion

The strategy of lowering therapeutic exposure has successfully translated to an observed decline in late mortality among 5-year survivors of childhood cancer.

Keywords: Pediatric, Cancer, Survivor, Mortality

In the 1960's less than half of children diagnosed with a malignancy achieved five-year survival.1 Now, over 83% of children diagnosed with cancer in the United States will become five-year survivors of their disease.2 As a result, in 2013 it was estimated that there were over 420,000 survivors of childhood cancer in the United States, and that by the year 2020 this number would surpass 500,000.3 Increased success in treatment of childhood cancers has been achieved through the systematic conduct of clinical trials assessing the efficacy of multimodal approaches involving combination chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and/or surgery along with increased expertise in supportive care.4,5 Five-year overall survival has been the primary benchmark of therapeutic success. However, as five-year survival rates increased, it became clear that long-term survivors of childhood cancer were at increased risk for severe and life-threatening therapy-related late effects6-8 and excess late mortality (death ≥5 years from diagnosis).9-16 Previous work from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS) found that, by 30 years from diagnosis, 18% of five-year survivors had died.17

In more recent decades, risk-stratification of therapy has increasingly guided the design of treatment regimens for the majority of pediatric malignancies. Recent expansion of the CCSS cohort, which now includes survivors diagnosed across three decades (1970-1999), provides a unique opportunity to evaluate temporal changes in therapy and the impact of these changes on overall and cause-specific late mortality.

METHODS

Population

The CCSS is a multi-institutional, retrospective, hospital-based cohort study, with longitudinal follow-up of survivors of childhood cancer diagnosed and treated at 31 institutions in the US and Canada (https://ccss.stjude.org/). The 34,033 eligible subjects included those diagnosed with cancer before age 21, with initial treatment between January 1, 1970 and December 31, 1999 and alive at five years after diagnosis of leukemia, CNS malignancy, Hodgkin's lymphoma, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, Wilms’ tumor, neuroblastoma, soft tissue sarcoma, or a bone tumor representing approximately 20% of US children diagnosed with cancer during this time period. The cohort methodology and study design have been previously described in detail.18 The CCSS was approved by institutional review boards at the 31 participating centers. Participants provided informed consent.

Ascertainment of Cause of Death

Patients eligible for participation were included in a search for matching death records using the National Death Index through 2007. Underlying and multiple causes of death for deceased subjects using the International Classification of Disease – 9th and 10th Revision were provided by the National Death Index and identified the initiating cause of death using standardized rules useful for classification of deaths. For deaths that predated the National Death Index (i.e., those in 1975-1978, N=139), death certificates from states where deaths occurred were requested. Deaths were grouped into three mutually exclusive categories using ICD-9 and ICD-10 coding: 1) recurrence or progression of primary cancer; 2) external causes (accidents, suicides, poisonings, and other external causes; ICD 9: 800-999, ICD 10: V00-V99, Y00-Y89, X00-X99, W00-W99); and, 3) health-related causes including subsequent neoplasms (ICD 9: 140-239, ICD 10: C00- C97, D10-D36), cardiac (ICD 9: 390-398, 402, 404, 410-429, ICD 10: I00- I02, I05-I09, I11, I13, I14, I20-I28, I30-I52), pulmonary (ICD 9: 460-519, ICD 10: J00-J99), and all other causes.

Cancer Treatment Information

Cancer diagnosis and treatment data including chemotherapy and radiotherapy exposures were abstracted from medical records at treating institutions utilizing standardized CCSS protocols, for 24,243 survivors who provided authorization.19,20 For the 9,790 survivors for whom treatment information was not available, multiple imputation was utilized (see Statistical Methods below).

Statistical Methods

Late mortality was evaluated beginning at five years from diagnosis to either death or December 31, 2007, the last date of the National Death Index search. Cumulative incidence of cause-specific death was estimated, stratified by treatment eras defined by 5-year (or 10-year) intervals and by primary cancer diagnosis. Standardized mortality ratios (SMRs) were calculated to quantify the rate of mortality in the CCSS cohort, relative to the age-, calendar year-, and sex-specific rates of the US population.21

Multivariable piecewise exponential models were used to assess relative rates (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of death due to health-related causes in specific treatment eras, relative to a reference treatment era of 1970-1979, adjusting for sex, age at diagnosis, attained age (single-year age segments of the piecewise exponential regression, modeled by natural cubic splines with knots at 10, 20, 30 and 40 years) and primary cancer diagnosis. If changes in treatment were responsible for changes in mortality, adjustment for treatment should attenuate the observed effects of treatment eras. Thus, within specific primary cancer groups, change in mortality was evaluated comparing the treatment era effects with and without adjusting for the treatment variables in the model, adjusting for sex, age at diagnosis, and attained age.

To augment the regression-based analysis with a visual description of changes in treatment by era, “treatment scores” were calculated for individual survivors from the multivariable piecewise exponential model with treatment variables, adjusting for sex, age at diagnosis, and attained age but not including era: see Appendix 1 for the derivation and use of the “treatment score”.

For each survivor with missing treatment data, we applied multiple imputation22: see Appendix 2 for the details of the multiple imputation used and an associated sensitivity analysis. When the specific cause of death was unknown (n=440 Canadian cases), cause of death was imputed by the predictive mean matching method, using age at diagnosis, year of diagnosis, treatment institution, cancer diagnosis group, and treatment variables as predictors of causes of death (matching variables). For missing time of death (n=27), the multiple imputation method proposed by Taylor et al.23 was applied. Given that specific cause of death was not available for Canadian cases, a sensitivity analysis restricted to only US survivors was performed. Since no appreciable differences were found we present the original analysis results.

Because of the many comparisons made with these data, p-values for differences in mortality in specific cancer types or from specific causes should be regarded as exploratory.

RESULTS

The cohort of 34,033 eligible survivors, including over 9,000 survivors initially diagnosed in the 1970s, over 13,000 survivors from the 1980s and over 11,000 survivors from the 1990s (Table 1, Table S1), provided a total of 705,806 person-years of observation. Thirty percent of the population was between 30 and 39 years and 15% were older than 40 years of age at last follow-up (median 28.5 years, range 5.5-58.5 years). While overall 57% of the cohort received radiotherapy, 77% of survivors from the 1970s received radiotherapy compared to only 41% from the 1990s. In contrast, more survivors received chemotherapy including anthracyclines and alkylating agents in more recent eras, but the average cumulative dose of exposure was reduced in more recent eras (Table S2, Figures S1 and S2).

Table 1.

Demographic and primary cancer characteristics overall and by life status among five-year survivors of childhood cancer

| Total | Alive | Dead | |

|---|---|---|---|

| All Survivors* | 34033 | 30075 (88.4%) | 3958 (11.6%) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 18983 | 16628 (87.6%) | 2355 (12.4%) |

| Female | 15050 | 13447 (89.3%) | 1603 (10.7%) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic white | 21781 | 19575 (89.9%) | 2206 (10.1%) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 2022 | 1817 (89.9%) | 205 (10.1%) |

| Hispanic | 2287 | 2094 (91.6%) | 193 (8.4%) |

| Others | 2057 | 1849 (89.8%) | 208 (10.2%) |

| Unknown | 5886 | 4740 (80.5%) | 1146 (19.5%) |

| Treatment Era | |||

| 1970-1979 | 9416 | 7548 (80.2%) | 1868 (19.8%) |

| 1980-1989 | 13181 | 11699 (88.8%) | 1482 (11.2%) |

| 1990-1999 | 11436 | 10828 (94.7%) | 608 (5.3%) |

| Age at Diagnosis (years) | |||

| 0-4 | 13463 | 12319 (91.5%) | 1144 (8.5%) |

| 5-9 | 7826 | 6950 (88.8%) | 876 (11.2%) |

| 10-14 | 7144 | 6185 (86.6%) | 959 (13.4%) |

| 15-20 | 5600 | 4621 (82.5%) | 979 (17.5%) |

| Survival after Diagnosis (years) | |||

| 5-9 | 4210 | 2349 (55.8%) | 1861 (44.2%) |

| 10-14 | 6298 | 5523 (87.7%) | 775 (12.3%) |

| 15-19 | 5285 | 4758 (90.0%) | 527 (10.0%) |

| 20-24 | 6721 | 6343 (94.4%) | 378 (5.6%) |

| 25-29 | 5964 | 5692 (95.4%) | 272 (4.6%) |

| 30-34 | 4051 | 3924 (96.9%) | 127 (3.1%) |

| ≥35 | 1504 | 1486 (98.8%) | 18 (1.2%) |

| Diagnosis | |||

| Leukemia | 10199 | 9019 (88.4%) | 1180 (11.6%) |

| Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | 8500 | 7557 (88.9%) | 943 (11.1%) |

| Acute myeloid leukemia | 1222 | 1101 (90.1%) | 121 (9.9%) |

| Other leukemia | 477 | 361 (75.7%) | 116 (24.3%) |

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 4332 | 3647 (84.2%) | 685 (15.8%) |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 2837 | 2621 (92.4%) | 216 (7.6%) |

| CNS tumors | 6369 | 5443 (85.5%) | 926 (14.5%) |

| Astrocytoma | 3904 | 3383(86.7%) | 521 (13.3%) |

| Medulloblastoma, PNET | 1380 | 1133 (82.1%) | 247 (17.9%) |

| Other CNS | 1085 | 927 (85.4%) | 158 (14.6%) |

| Wilms tumor | 3055 | 2898 (94.9%) | 157 (5.1%) |

| Neuroblastoma | 2632 | 2457 (93.4%) | 175 (6.6%) |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | 1679 | 1510 (89.9%) | 169 (10.1%) |

| Bone tumors | 2930 | 2480 (84.6%) | 450 (15.4%) |

| Ewing sarcoma | 997 | 813 (81.5%) | 184 (18.5%) |

| Osteosarcoma | 1771 | 1518 (85.7%) | 253 (14.3%) |

| Other bone tumors | 162 | 149 (92.0%) | 13 (8.0%) |

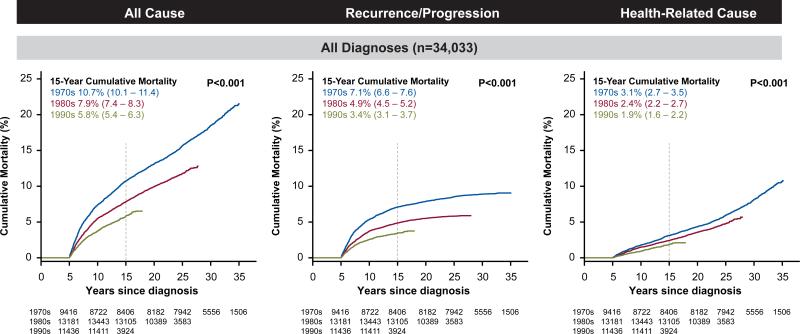

There were 3,958 deaths among the cohort, with 2,002 attributable to recurrence/progression of the primary cancer, 338 to external causes and 1,618 attributable to health-related causes including 746 to subsequent neoplasms, 241 cardiac deaths and 137 pulmonary deaths. At 15 years from diagnosis, the cumulative incidence for all-cause mortality for survivors diagnosed in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s was 10.7%, 7.9% and 5.8%, respectively (P<0.001; Figure 1, Figure S1, Table S3). Across these decades the cumulative incidence of death due to recurrence or progression of primary cancer decreased from 7.1% to 4.9% and 3.4% (P<0.001). Death from health-related causes, which includes deaths from late effects of cancer therapy, decreased from 3.1%, to 2.4 % and 1.9% (P<0.001) and reflected statistically significant reductions in mortality from subsequent malignant neoplasms, cardiac and pulmonary related diseases/events across three decades (Table 2, Table S4). In a multivariable model adjusting for cancer diagnosis, age at diagnosis, sex and follow-up time, there was a reduced rate of death associated with more recent treatment eras. The adjusted relative rate per every 5 years was statistically significantly different than 1.0, not only for any health-related cause (RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.82-0.89; Table S5), but also for cause-specific mortality related to subsequent malignant neoplasms (RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.78-0.88), cardiac (RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.68-0.86) and pulmonary conditions (RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.66-0.89). Similar patterns were seen in reductions in SMRs (Table S6).

Figure 1.

Cumulative all-cause, recurrence/progression and health-related cause late mortality among five-year survivors of childhood cancer by decade.

Table 2.

Cumulative incidence of all cause and cause-specific mortality at 15 years from primary cancer diagnosis among five-year survivors

| Primary Cancer Diagnosis | Year of Diagnosis | All Cause | Recurrence/Progression of Primary Disease | Health-related Cause | Subsequent Neoplasm | Cardiac | Pulmonary | Other Health-related Causes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All diagnoses | 1970-1974 | 12.4% | 8.4% | 3.5% | 1.8% | 0.47% | 0.45% | 0.85% |

| 1975-1979 | 9.7% | 6.2% | 2.9% | 1.5% | 0.42% | 0.19% | 0.76% | |

| 1980-1984 | 8.8% | 5.5% | 2.7% | 1.3% | 0.32% | 0.26% | 0.75% | |

| 1985-1989 | 6.9% | 4.2% | 2.2% | 1.3% | 0.14% | 0.16% | 0.54% | |

| 1990-1994 | 6.0% | 3.6% | 2.1% | 1.0% | 0.13% | 0.11% | 0.85% | |

| P value | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 0.001 | 0.04 | 0.13 | |

| Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | 1970-1974 | 16.6% | 13.0% | 3.2% | 0.9% | 0.63% | 0.40% | 1.23% |

| 1975-1979 | 11.4% | 8.5% | 2.6% | 1.2% | 0.36% | 0.10% | 0.93% | |

| 1980-1984 | 9.1% | 6.6% | 2.0% | 1.1% | 0.07% | 0.14% | 0.69% | |

| 1985-1989 | 6.9% | 4.0% | 2.6% | 1.9% | 0.05% | 0.17% | 0.51% | |

| 1990-1994 | 4.6% | 2.0% | 2.1% | 1.4% | 0.05% | 0 | 0.64% | |

| P value | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 0.14 | 0.003 | 0.05 | <.001 | |

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 1970-1974 | 13.1% | 6.9% | 5.3% | 2.9% | 0.88% | 0.91% | 0.65% |

| 1975-1979 | 8.6% | 4.8% | 3.3% | 2.0% | 0.54% | 0.65% | 0.76% | |

| 1980-1984 | 8.8% | 3.2% | 4.6% | 1.9% | 1.30% | 0.48% | 0.89% | |

| 1985-1989 | 5.3% | 2.9% | 1.9% | 1.1% | 0.49% | 0 | 0.31% | |

| 1990-1994 | 5.8% | 2.7% | 2.6% | 1.3% | 0.46% | 0.46% | 0.88% | |

| P value | <.001 | <.001 | 0.006 | 0.19 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.69 | |

| Wilms tumor | 1970-1974 | 4.2% | 1.6% | 2.6% | 1.9% | 0.30% | 0.91% | 0.42% |

| 1975-1979 | 3.3% | 1.1% | 1.9% | 0.4% | 0.83% | 0.65% | 0.62% | |

| 1980-1984 | 2.5% | 1.3% | 0.8% | 0.5% | 0 | 0.48% | 0.32% | |

| 1985-1989 | 2.3% | 1.9% | 0.4% | 0 | 0.19% | 0 | 0.19% | |

| 1990-1994 | 2.3% | 1.6% | 0.4% | 0 | 0 | 0.46% | 0.36% | |

| P value | 0.37 | 0.80 | 0.005 | <.001 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.83 | |

| Astrocytoma | 1970-1974 | 13.5% | 8.5% | 4.7% | 2.1% | 0.89% | 0.52% | 1.18% |

| 1975-1979 | 12.2% | 7.2% | 4.1% | 2.4% | 0.21% | 0.42% | 1.09% | |

| 1980-1984 | 11.3% | 7.7% | 3.0% | 1.8% | 0.15% | 0.55% | 0.56% | |

| 1985-1989 | 7.1% | 4.8% | 1.9% | 0.9% | 0.15% | 0.13% | 0.85% | |

| 1990-1994 | 7.4% | 5.4% | 1.8% | 0.5% | 0 | 0.24% | 0.99% | |

| P value | <0.001 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.72 | 0.84 |

Statistically significant reduction in mortality due to any health-related cause across treatment eras was observed in survivors of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (3.2% to 2.1%, P<0.001); Table 2), Hodgkin's lymphoma (5.3% to 2.6%, P=0.006), Wilms’ tumor (2.6% to 0.4%, P=0.005) and astrocytoma (4.7% to 1.8%, P=0.02), but not in the other primary cancer groups. Cardiac mortality declined statistically significantly in acute lymphoblastic leukemia (0.36% to 0.05%, P=0.003), Hodgkin's lymphoma (0.88% to 0.46%, P=0.06), Wilms’ tumor (0.30% to 0.19%, P=0.04) and astrocytoma (0.89% to 0.15%, P=0.02), while mortality from subsequent neoplasms was statistically significantly reduced in survivors of Wilms’ tumor (1.9% to 0.49%, P<0.001).

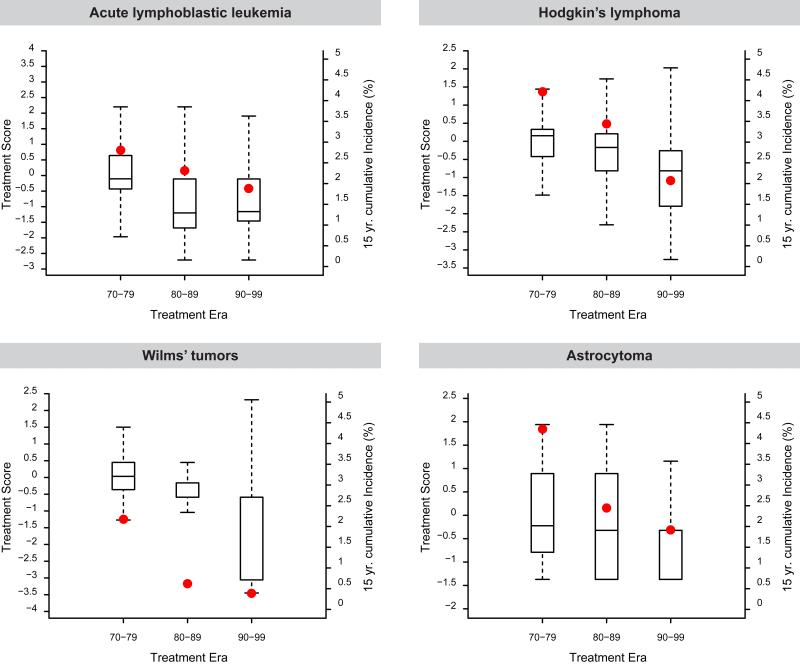

Notably, temporal reductions in exposure of exposure for radiotherapy and anthracyclines were observed for acute lymphoblastic leukemia, Hodgkin's lymphoma, Wilms’ tumor and astrocytoma (Table S2, Figures S2 and S3). For the diagnoses of acute lymphoblastic leukemia, Hodgkin's lymphoma, Wilms’ tumor and astrocytoma, temporal reductions in 15-year health-related cause mortality followed temporal reductions in therapeutic exposure (Figure 2). The impact of treatment era on the rate of death from a health-related cause was assessed in multivariable models with and without adjustment for therapy (Table 3, Table S7). The effect of treatment era on the relative rate of health-related cause mortality was attenuated by the inclusion of therapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (RR = 0.88 without treatment in the model compared to RR = 1.02 with treatment in the model) and Wilms’ tumor (RR 0.68 to 0.80), but not for Hodgkin's lymphoma (RR 0.79 in both models), or astrocytoma (RR 0.81 to 0.82).

Figure 2.

Median treatment intensity scores shown as 25th and 75th percentile box plots (left y-axis) and 15-year cumulative health-related cause late mortality (red dot, right y-axis) among five-year survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia, astrocytoma, Hodgkin's lymphoma and Wilms’ tumor by decade.

Table 3.

Relative rates of health-related cause mortality based on treatment era among five-year survivors of specific childhood cancers and the impact of specific treatment exposures on treatment era*

| Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia | Hodgkin Lymphoma | Wilms Tumor | Astrocytoma | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR | 95%CI | RR | 95%CI | RR | 95%CI | RR | 95%CI | |

| Model Without Therapy | ||||||||

| Treatment era (per 5 years) | 0.88 | 0.81 - 0.95 | 0.79 | 0.72 - 0.87 | 0.68 | 0.56 - 0.84 | 0.81 | 0.73 - 0.91 |

| Model With Therapy | ||||||||

| Treatment era (per 5 years) | 1.021 | 0.83 - 1.24 | 0.792 | 0.70 - 0.89 | 0.803 | 0.59 - 1.08 | 0.824 | 0.72 - 0.94 |

all models adjusted for sex, age at diagnosis and attained age

Adjusted for cranial RT dose, anthracycline dose, epipodophyllotoxin and steroid exposure

adjusted for chest-directed radiotherapy dose, anthracycline dose, cyclophosphamide equivalent dose and splenectomy

adjusted for abdominal RT dose and anthracycline dose

adjusted for cranial RT dose and any chemotherapy (yes/no).

DISCUSSION

Treatment approaches for pediatric cancers have evolved over the past five decades with the global objective of sustainable or increasing cure while minimizing risk for acute and long-term toxicities.4,24 The current analysis confirms previously published data demonstrating that more recently treated patients have a significantly lower rate of late mortality attributable to deaths from recurrence or progression of their primary cancer.10,25-27 What has not been documented previously is the reduced rate of mortality due to death from treatment-related late effects such as subsequent malignancies and cardiopulmonary conditions. Additionally, the results generated from the CCSS cohort, provide evidence that the strategy of reduced treatment exposure to decrease the frequency of late effects is translating into a significant reduction in observed late mortality, extending the lifespan of children and adolescents successfully treated for cancer.

Appreciation of the risk for long-term adverse consequences of therapy6-8 resulted in the design and testing of newer treatment regimens to reduce the potential for late effects. This was generally achieved by reduction in therapeutic exposures for patients considered to be at low risk for recurrence of the primary malignancy, while providing therapy that would maintain or improve long-term disease-free survival.14,28-36 The availability of treatment exposure data in the CCSS cohort, including cumulative doses of most chemotherapeutic exposures and organ-specific radiotherapy dosimetry, provided a unique opportunity to evaluate whether the risk reduction observed in more recent treatment eras was directly associated with reduction in therapeutic exposure. We observed temporal reductions in health-related mortality concurrent with reduction in therapeutic exposure among acute lymphoblastic leukemia and Wilms’ tumor survivors. However, for Hodgkin's lymphoma and astrocytoma our findings suggest that factors other than reduced treatment exposures may have caused the observed reductions in late health-related mortality. Potential contributors to decreased late mortality include increased utilization and accuracy of screening modalities.37-39 While evidence suggests that guideline-based screening and care is not universal,40 it should be expected that these efforts would have a positive impact on health-related mortality. Finally, over the past several decades, there have been improvements in medical care that may delay or prevent death from late effects of therapy. However, our ability to directly measure these changes in the CCSS population is limited. It is also notable that for certain malignancies, primarily neuroblastoma, there is an increase in late mortality in more recent decades, presumably attributable to increased therapeutic intensity that resulted in improved five-year survival yet with an increased risk of late effects and delayed recurrence or progression of the primary cancer.

Importantly, the overall decrease in all-cause mortality is primarily attributable to reduction in death due to recurrence or progression of primary cancer, consistent with previous studies12,26 suggesting that survivors who achieve 5-year survival in more recent eras experience more durable remissions, or respond more favorably to therapy for relapse or recurrence of their primary cancers. Combined improvements in treatment of the primary cancer and reductions in health-related mortality result in an almost 50% decline in all-cause late mortality for survivors of childhood cancer (10.7% at 15 years post-diagnosis among survivors from the 1970s to 5.8% in the modern era).

While our previous report using registry-based data suggested that survivors in more recent eras may be at lower risk for death due to late effects of cancer therapy25, the large size of the CCSS cohort with detailed treatment information, provides compelling evidence for reduction in subsequent neoplasm, cardiac and pulmonary late mortality by decade. Interpretation of the current findings need to consider the following limitations: (1) the outcome of health-related causes of death does not allow direct attribution of death to sequelae from treatment of childhood cancer; (2) the inability to quantify and directly consider temporal changes in medical care; (3) a potential for bias resulting from shorter follow-up for survivors from the 1990s, though 10-year patterns appear consistent to 15-year mortality (Table S8); and, (4) the current analysis did not evaluate temporal trends in the incidence of specific treatment-related chronic health conditions that could increase the risk of death.

In conclusion, the impact of pediatric cancer treatment regimens designed to reduce the potential risk and severity of late effects is now being confirmed through the study of long-term survivors. Along with increased promotion of approaches for early detection of late effects and improvements in medical care for late effects of therapy, quantitative evidence now shows that this approach has resulted in lifespan extension for many survivors of childhood cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was presented at the plenary session of the American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting, Chicago, 2015

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute (CA55727, G.T. Armstrong, Principal Investigator). Support to St. Jude Children's Research Hospital also provided by the Cancer Center Support (CORE) grant (CA21765, C. Roberts, Principal Investigator) and the American Lebanese-Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This file is the accepted version of your manuscript, and it shows any changes made by the Editor-in-Chief and the Deputy Editor since you submitted your last revision. This is the version that is being sent to Manuscript Editing for further editing in accordance with NEJM style. You will receive proofs of the edited manuscript, by e-mail. The proofs will contain queries from the manuscript editor, as well as any queries that may be present in this file. The proof stage will be your next opportunity to make changes; in the meantime, please do not make any changes or send any new material to us.

Disclosure:

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

References

- 1.Ries LG, Pollack ES, Young JL., Jr. Cancer patient survival: Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program, 1973-79. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1983;70:693–707. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2012. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robison LL, Hudson MM. Survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer: life-long risks and responsibilities. Nature reviews Cancer. 2014;14:61–70. doi: 10.1038/nrc3634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hudson MM, Neglia JP, Woods WG, et al. Lessons from the past: opportunities to improve childhood cancer survivor care through outcomes investigations of historical therapeutic approaches for pediatric hematological malignancies. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;58:334–43. doi: 10.1002/pbc.23385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Green DM, Kun LE, Matthay KK, et al. Relevance of historical therapeutic approaches to the contemporary treatment of pediatric solid tumors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:1083–94. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, et al. Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1572–82. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa060185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Armstrong GT, Kawashima T, Leisenring W, et al. Aging and risk of severe, disabling, life-threatening, and fatal events in the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1218–27. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hudson MM, Ness KK, Gurney JG, et al. CLinical ascertainment of health outcomes among adults treated for childhood cancer. JAMA. 2013;309:2371–81. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.6296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mertens AC, Yasui Y, Neglia JP, et al. Late mortality experience in five-year survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer: the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3163–72. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.13.3163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hudson MM, Jones D, Boyett J, Sharp GB, Pui CH. Late mortality of long-term survivors of childhood cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:2205–13. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.6.2205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mertens AC, Liu Q, Neglia JP, et al. Cause-specific late mortality among 5-year survivors of childhood cancer: the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1368–79. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moller TR, Garwicz S, Barlow L, et al. Decreasing late mortality among five-year survivors of cancer in childhood and adolescence: a population-based study in the Nordic countries. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3173–81. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.13.3173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li FP, Myers MH, Heise HW, Jaffe N. The course of five-year survivors of cancer in childhood. J Pediatr. 1978;93:185–7. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(78)80492-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pui CH, Cheng C, Leung W, et al. Extended follow-up of long-term survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:640–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reulen RC, Winter DL, Frobisher C, et al. Long-term cause-specific mortality among survivors of childhood cancer. JAMA. 2010;304:172–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cardous-Ubbink MC, Heinen RC, Langeveld NE, et al. Long-term cause-specific mortality among five-year survivors of childhood cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2004;42:563–73. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Armstrong GT, Liu Q, Yasui Y, et al. Late mortality among 5-year survivors of childhood cancer: a summary from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2328–38. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robison LL, Armstrong GT, Boice JD, et al. The Childhood Cancer Survivor Study: a National Cancer Institute-supported resource for outcome and intervention research. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2308–18. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.3339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leisenring WM, Mertens AC, Armstrong GT, et al. Pediatric cancer survivorship research: experience of the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2319–27. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.1813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stovall M, Weathers R, Kasper C, et al. Dose reconstruction for therapeutic and diagnostic radiation exposures: use in epidemiological studies. Radiat Res. 2006;166:141–57. doi: 10.1667/RR3525.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.United States Department of Health and Human Servies Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics Compressed Mortatlity File on CDC Wonder Online Database; CMF 1999-2013, Series 20, No 2s, 2014; CMF 1968-1988, Series 20, No. 2A, 2000; CMF 1989-1998, Series 20, No. 2E. 2003 http://wonder.cdc.gov/wonder/help/cmf.html. CDC Wonder 1968-2013.

- 22.Little RJA. Statistical Analysis of Missing Data. John Willey & Sons; New York, NY: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taylor JM, Munoz A, Bass SM, Saah AJ, Chmiel JS, Kingsley LA. Estimating the distribution of times from HIV seroconversion to AIDS using multiple imputation. Multicentre AIDS Cohort Study. Stat Med. 1990;9:505–14. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780090504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Green DM, Kun LE, Matthay KK, et al. Relevance of historical therapeutic approaches to the contemporary treatment of pediatric solid tumors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013 doi: 10.1002/pbc.24487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Armstrong GT, Pan Z, Ness KK, Srivastava D, Robison LL. Temporal trends in cause-specific late mortality among 5-year survivors of childhood cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1224–31. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.4608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garwicz S, Anderson H, Olsen JH, et al. Late and very late mortality in 5-year survivors of childhood cancer: changing pattern over four decades--experience from the Nordic countries. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:1659–66. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moller TR, Garwicz S, Perfekt R, et al. Late mortality among five-year survivors of cancer in childhood and adolescence. Acta Oncol. 2004;43:711–8. doi: 10.1080/02841860410002860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pui CH, Campana D, Pei D, et al. Treating childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia without cranial irradiation. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2730–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0900386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sullivan MP, Chen T, Dyment PG, Hvizdala E, Steuber CP. Equivalence of intrathecal chemotherapy and radiotherapy as central nervous system prophylaxis in children with acute lymphatic leukemia: a pediatric oncology group study. Blood. 1982;60:948–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Conklin HM, Krull KR, Reddick WE, Pei D, Cheng C, Pui CH. Cognitive outcomes following contemporary treatment without cranial irradiation for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:1386–95. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Donaldson SS, Link MP. Combined modality treatment with low-dose radiation and MOPP chemotherapy for children with Hodgkin's disease. J Clin Oncol. 1987;5:742–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1987.5.5.742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schwartz CL, Constine LS, Villaluna D, et al. A risk-adapted, response-based approach using ABVE-PC for children and adolescents with intermediate- and high-risk Hodgkin lymphoma: the results of P9425. Blood. 2009;114:2051–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-184143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.D'Angio GJ, Breslow N, Beckwith JB, et al. Treatment of Wilms’ tumor. Results of the Third National Wilms’ Tumor Study. Cancer. 1989;64:349–60. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19890715)64:2<349::aid-cncr2820640202>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lipshultz SE, Colan SD, Gelber RD, Perez-Atayde AR, Sallan SE, Sanders SP. Late cardiac effects of doxorubicin therapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia in childhood. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:808–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199103213241205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Green DM, Breslow NE, Beckwith JB, et al. Effect of duration of treatment on treatment outcome and cost of treatment for Wilms’ tumor: a report from the National Wilms’ Tumor Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:3744–51. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.12.3744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Packer RJ, Ater J, Allen J, et al. Carboplatin and vincristine chemotherapy for children with newly diagnosed progressive low-grade gliomas. J Neurosurg. 1997;86:747–54. doi: 10.3171/jns.1997.86.5.0747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Henderson TO, Amsterdam A, Bhatia S, et al. Systematic review: surveillance for breast cancer in women treated with chest radiation for childhood, adolescent, or young adult cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:444–55. W144–54. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-152-7-201004060-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hudson MM, Leisenring W, Stratton KK, et al. Increasing cardiomyopathy screening in at-risk adult survivors of pediatric malignancies: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3974–81. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.3493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kremer LC, Mulder RL, Oeffinger KC, et al. A worldwide collaboration to harmonize guidelines for the long-term follow-up of childhood and young adult cancer survivors: a report from the International Late Effects of Childhood Cancer Guideline Harmonization Group. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:543–9. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nathan PC, Ford JS, Henderson TO, et al. Health behaviors, medical care, and interventions to promote healthy living in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study cohort. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2363–73. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.1441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.