Abstract

Training effects on plasma insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1)/cortisol ratio were investigated in boxers. Thirty subjects were assigned to either the training or the control group (n = 15 in both). They were tested before the beginning of training (T0), after 5 weeks of intensive training (T1), and after 1 week of tapering (T2). Physical performances (Yo-Yo intermittent recovery test level-1), training loads, and blood sampling were obtained at T0, T1, and T2. Controls were only tested for biochemical and anthropometric parameters at T0 and T2. A significantly higher physical performance was observed at T2 compared to T1. At T1, cortisol levels were significantly increased whereas IGF-1 and insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 (IGFBP-3) levels remained unchanged compared to baseline. At T2, cortisol levels decreased while IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 levels increased. The IGF-1/cortisol ratio decreased significantly at T1 and increased at T2, and its variations were significantly correlated with changes in training loads and Yo-Yo intermittent recovery test level 1 (IRT1) performance over the training period. Cortisol variations correlated with changes in training load (r = 0.64; p < 0.01) and Yo-Yo IRT1 performance (r = 0.78; p < 0.001) at T1 whereas IGF-1 variations correlated only with changes in Yo-Yo IRT1 performance at T2 (r = 0.71; p < 0.001). It is concluded that IGF-1/cortisol ratio could be a useful tool for monitoring training loads in young trained boxers.

Keywords: Training intensity, Hormonal responses, Physiological demands, biochemical factor, Physical performance

INTRODUCTION

Boxing training is challenging as it requires high-intensity training concomitantly to the management of body weight, which may interfere with the improvement of physical performance [1]. The improvement of physical performance is also quite a sensitive approach that requires a significant amount of high-intensity training with the risk of being exposed to acute fatigue, overreaching, or even overtraining [2]. In this context, to avoid excessive fatigue or overtraining, monitoring of training load and training outcomes is necessary. Several monitoring methods have been used by coaches/sport scientists to assess the physical training loads undertaken by athletes [3, 4]. The most widely used method for evaluating internal training load was the assessment of heart rate as a determinant of exercise intensity [5]. However, this method presents several limitations for some uses; for instance, its use for weight, interval, intermittent, and/or plyometric training is questionable [3]. Recently, the session rating of perceived exertion (RPE) method for quantifying training loads has become a useful tool for both monitoring and optimizing training [3, 6]. This method is recognized as simple, practical and, more importantly, has been validated in several sport activities for different applications [3, 4].

It is well known that physical exercise training is considered as a powerful stimulus of corticotropic and somatotropic axes resulting in diverse responses. In that regard, cortisol has been shown to be an indicator of poor adaptation to training thus leading to performance decrements and accumulation of fatigue, indicating a catabolic state of the athlete [2]. Likewise, it has also been reported that cortisol resting levels increase [7, 8], remain stable [9, 2] or even decrease [10] over training programmes’ fluctuations. The effects of training on somatotropic axis responses also showed controversial results. Indeed, most studies reported an increase in plasma resting insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) levels during training [11]. Others report either no changes [13] or even a decreased concentration of IGF-1 [12]. Similarly, the conclusions concerning the effects of training programmes on insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 (IGFBP-3), which is the main protein transporter of IGF-1, also present different outcomes [12]. The decrease of its concentration is related to the increase of training loads [12]. Schwarz [14], showed that, after 10 minutes of low-intensity exercise, at first, the rate of IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 increased over the pre-exercise baseline by 7.7 ± 2.7% and 12.5 ± 3.3%, respectively, then after 10 min of high-intensity exercise, the rate of IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 increased over the pre-exercise baseline by 13.3 ± 3.2% and 23 ± 6%, respectively [14]. However, among adolescent volleyball players, after 1 hour of volleyball practice, there were no significant changes in IGF-I and IGFBP-3 levels and only an increase in growth hormone (GH) [12]. A study from our group showed that elevated basal concentration of GH, IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 was observed in the high level training group after 18 months of intensive training compared to controls [15]. These results confirm those reported by Nebigh et al. [16], who showed that, in prepubescent soccer-playing boys, IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 were higher than in a control group [16].

Additionally, it has been well established that IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 circulating levels are regulated by several factors such as nutrition, age, pregnancy, chronic diseases, insulin, and growth hormone, amongst others [12]. Moreover, IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 represent good markers of the athletes’ physical fitness, since positive correlations have been found between IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 levels and maximum oxygen uptake in several trained athletes, thus reflecting their anabolic state [17].

Several authors have examined the anabolic/catabolic activity of athletes during training. They suggested the testosterone/cortisol ratio as a useful marker of this activity and an indicator of training stress and fatigue [2, 8]. Nevertheless, no study has reported the variation of IGF-1/cortisol ratio in boxers during training, which may reflect the anabolic/catabolic activities of their organisms. Based on these considerations, the aim of the present study was to investigate the effects of training load variations on plasma IGF-1/cortisol ratio in trained boxers, and to determine the usefulness of this ratio as a possible marker of training load and performance.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

Fifteen young male boxers and fifteen age- and puberty-matched controls aged 14 to 16 years volunteered to participate in this longitudinal design study. The physical characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1. Athletes were recruited from a regional selection (the two largest boxing clubs in the country). Boxers had been practising their sport for at least 5 years with a mean training schedule of 10-12 hours per week including combats. They had a minimum of 3 years of competitive experience each in regional and national tournaments. Athletes ranged in weight categories from fly (over 49 kg to 52 kg) to bantam (over 52 kg to 56 kg) according to the Amateur International Boxing Association, Open Boxing Competition Rules 2013. The control participants were 15 age- and puberty-stage-matched moderately active school students performing no more than 2 h of school physical education weekly. Before beginning experimental procedures, all participants and their parents were given written information about the risks and benefits of the study and signed written consent. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee at the University of Medicine of Sousse, Tunisia and was in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (1975). Prior to taking part in this protocol, the participants were examined by a physician to detect any medical disorders that might limit their full participation in the investigation. None of the participants had taken or planned to take any medication, supplements, exogenous anabolic-androgenic steroids or any other substances expected to affect hormonal balance during this study. Pubertal stages were evaluated according to the Tanner classification [18] by the same trained physician. Pre-pubertal children are children who were in stage I, pubertal children are children who were in stages II-III, post-pubertal children are children who were in stages IV-V.

TABLE 1.

Anthropometric, hormonal, and performance data of the study participants.

| Controls ± n = 15 | Boxers ± n = 15 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | T0 | T2 | T0 | T1 | T2 |

| Age ± yrs | 14.7 ± 0.5 | 14.8 ± 0.6 | |||

| Height (m) | 1.65 ± 0.04 | 1.64 ± 0.06 | |||

| Puberty stage | 4.5 ± 0.4 | 4.6 ± 0.5 | |||

| Weight (kg) | 62.4 ± 4.9 | 62.1 ± 5.2 | 46.3±5.9 | 44.6 ± 5.5 ££ | 44.8 ± 5.4 ** |

| BMI (kg·m−2) | 22.7 ± 0.9 | 22.7 ± 1.1 | 17.2 ± 1.4 | 16.5 ± 1,3 ££ | 16.6 ± 1.3 ** |

| Fat mass (%) | 28.8 ± 3.4 | 28.7 ± 4.2 | 16.45 ± 1.42 | 12.84 ± 1.13 ££ | 12.31 ± 1,51 ££ |

| Fat free mass (kg) | 44.5 ± 4.6 | 44.6 ± 5.1 | 38.49 ± 4.07 | 38.74 ± 4.10 ** | 39.17 ± 4.08 ** |

| Energy intake (kcal·d−1) | 2731 ± 87 | 2697 ± 100 | 2987 ± 56 | 3007 ± 66 | 2979 ± 88 |

| Carbo-Hydrates (%) | 45.5 ± 1.3 | 46.4 ± 1.0 | 52.0 ± 5.5 | 51.5 ± 4.8 | 51.8 ± 4.3 |

| Lipids (%) | 36.5 ± 0.1 | 35.5 ± 0.5 | 30.3 ± 4.0 | 30.1 ± 4.7 | 30.1 ± 5.2 |

| Proteins (%) | 18.0 ± 0.3 | 18.1 ± 0.4 | 17.7 ± 1.8 | 18.4 ± 1.1 | 18.2 ± 1.3 |

| Cortisol (ng·ml−1) | 50.7 ± 10.2 | 50.9 ± 10.6 | 50.4 ± 14.3 | 56.1 ± 16.8 ** | 50.5 ± 14.0 ££ |

| IGF-1 (ng·ml−1) | 404.1 ± 59.9 | 402.7 ± 63.2 | 437.6 ± 115.6 | 443.0 ± 116.0 | 488.4 ± 113.9 ** |

| IGF-1/Cortisol | 8.1 ± 0.9 | 7.9 ± 1.2 | 9.4 ± 4.0 | 8.6 ± 3.4 | 10.6 ± 4.6 ** |

| IGFBP-3 (ng·ml−1) | 3646.7 ± 781.2 | 3652.2 ± 659.7 | 3751.7 ± 760.5 | 3997.4 ± 783.9 | 4304.7 ± 833.4 ** |

| Hand grip Force (kg) | 29.75 ± 4.81 | 28.83 ± 4.88 ££ | 31.20 ± 4.81 ** | ||

| Yo-Yo IRT1 performance (m) | 1333.3 ± 57.9 | 1281.3 ± 59.7 ££ | 1389.3 ± 57.5 ** | ||

Note: IGF-1: insulin-like growth factor-1; IGFBP-3: insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3; Yo-Yo IRT1: Yo-Yo intermittent recovery test level 1; T0: before training; T1: after 5 weeks of intensive training; T2, after one week of tapering consecutive to intensive training *: superior to the precedent value; * p < 0.05

p < 0.01; £: inferior to the precedent value

p < 0.01. Values are given as the mean ± SD.

Experimental protocol

The present study was designed to determine the effects of an intensive training programme, assessed by the session RPE method, on hormonal and physical performance responses in young male boxers. During the whole programme, training sessions were designed and implemented by the boxers’ coaches with only measures and no input from the researchers.

Anthropometric measurements, blood sampling, and physical testing were performed three times at the National Center of Medicine and Science in Sports, Tunis: (i) one day preceding the start of the training programme (T0, reference value), (ii) after 5 weeks of intense training (T1) and (iii) after 1 week of successive tapering (T2). Boxers did not have any intense training 2 days preceding each measurement and had a resting day the day before. All measurements were made by the same investigators.

Anthropometric measures

Body mass (also practically called weight) and height were measured with calibrated devices (Tanita, Model, and Harpenden Portable Stadiometer). The percentage of body mass fat was calculated using the equation of Slaughter et al. [19] with triceps and subscapular skinfolds using a clamp mark Harpenden caliper (Holtain Ltd Bryberian, UK).

Testing procedures

Physical tests included different aspects of physical fitness of boxing. During the familiarization period of training, all physical testing was performed on two occasions at least 72 h apart to establish test-retest reproducibility. The choice and the setup of these tests were elaborated by the coaches of these teams. Boxers performed the following selected tests:

Strength grip was determined on a calibrated handgrip dynamometer with visual feedback (Harpenden Dynamometer, British Indicators, Ltd. UK). The dynamometer was adjusted to each subject's hand using the dominant hand used for data analysis. The best of three maximal trials with 1-min recovery in between was used for analysis [20].

Aerobic fitness was evaluated three times during the training period by the Yo-Yo intermittent recovery test level 1 (Yo-Yo IRT1) according to the protocol described by Krustrup et al. [21] Briefly, the subjects performed 2×20-m shuttle running bouts interspersed with 10-second recovery until exhaustion at a progressive speed dictated by calibrated pre-recorded audio cues. The result of Yo-Yo IRT1, represented by the total distance covered, showed an association with the general population's maximum oxygen intake. One week before the final measurements a pilot study was conducted among 20 athletes in order to examine the reliability of the field tests.

Training

The training programme performed by the experimental group represented the typical training programme usually performed by elite boxers. The aim of this programme was to develop physical, technical, and tactical aspects of the fight before an upcoming competition. Both training volume and intensity were relatively high; the weekly training programme included 5-6 training sessions lasting 12 hours approximately (5 days/week, ∼2 hours/day). The boxers underwent the training programme set by their team coaches, which consisted of 25 sessions completed over 5 weeks. Their regular boxing training consisted mainly of a repetitive series of short and intense exercises involving various components within a boxing session. The exercises proposed during the sessions were varied, including warm-up technical and tactical shadow boxing, sparring and/or sport-specific tactical drills, sport-specific interval training, pad work, punching bag, aerobic training, and individual technical skills. Boxers also performed gym sessions that aimed at developing strength and explosive force during the training programme.

Training load monitoring

The training load for the whole study period was assessed according to the method of Foster et al. [3]. This method was used as a measure of the training session intensity. Each boxer's RPE was collected ∼15 minutes after the end of every training session. In this study, as subjects were currently speaking French, a validated French translation of the category-ratio CR-10 scale modified from Foster et al. [21] was used. All boxers who participated in this study had been familiarized with this scale for session RPE before the beginning of the study. Additionally, the training monotony, with reference to session RPE variables which represent the measure of day-to-day training variability, was calculated [23]. The mean training load and monotony were also calculated during the 5-week intense training for comparison with the 1-week tapering period.

Food intake assessment

To assess the adequacy of food intake, a 7-day consecutive dietary record was maintained [11]. Both boxers and controls received a detailed verbal explanation and written instructions on data collection procedures. Participants were asked to continue with their usual dietary habits during the period of diet recording, and to be as accurate as possible in recording the amount and type of food and fluid ingested. A list of common household measures, such as cups, tablespoons, and specific information about the quantity in each measurement (grams, cl), was given to each participant. Each individual's diet was calculated using the validated Bilnut 4 software package (SCDA Nutrisoft, Cerelles, France), a computerized database that calculates food intake and composition from the standard references of the National Institute of Statistics of Tunisia.

Blood sampling

Blood samples were collected three times (T0, T1, and T2) during the study in order to assess hormonal variations during training. To avoid any confounding effects of variations in circadian rhythm and food intake on hormonal secretion, boxers and controls provided blood samples when getting up in a fasted state (resting values, about 8:00 a.m.). Plasma cortisol measurement was performed in duplicate single assay using commercially prepared RIA kits (GammaCoat [125I], Diasorin, Stillwater, MN). The intra-assay coefficient of variation was 6%. Plasma total IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 were determined by immuno-radiometric essay (Immunotech Kit, Marseille France). The intra- and inter-essay coefficients of variation were 6.3 and 6.8% for IGF-1 at serum concentration of 2 ng/ml, and 6.0 and 9.5 for IGFBP-3 at serum concentration of 50 ng/ml, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Statistical tests were processed using the SPSS software statistical package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, version. 16.0). Mean and standard deviation (SD) were calculated for the selected variables. The Shapiro-Wilk W-test of normality revealed that the data were normally distributed. Once the verification of normality was confirmed, parametric tests were performed. One-way, repeated ANOVA tests were performed to analyse the mean differences between the three training periods. If significant main effects were observed, a Bonferroni post-hoc analysis was performed to pinpoint the difference. Effect sizes (ES) were also calculated and reported according to Cohen [24] [small: < 0.4, moderate: 0.4 to 0.70, and large: > 0.70]. The test-retest reliability was expressed by intra-class correlation coefficients (ICCs), and standard error of measurement (SEM). Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

RESULTS

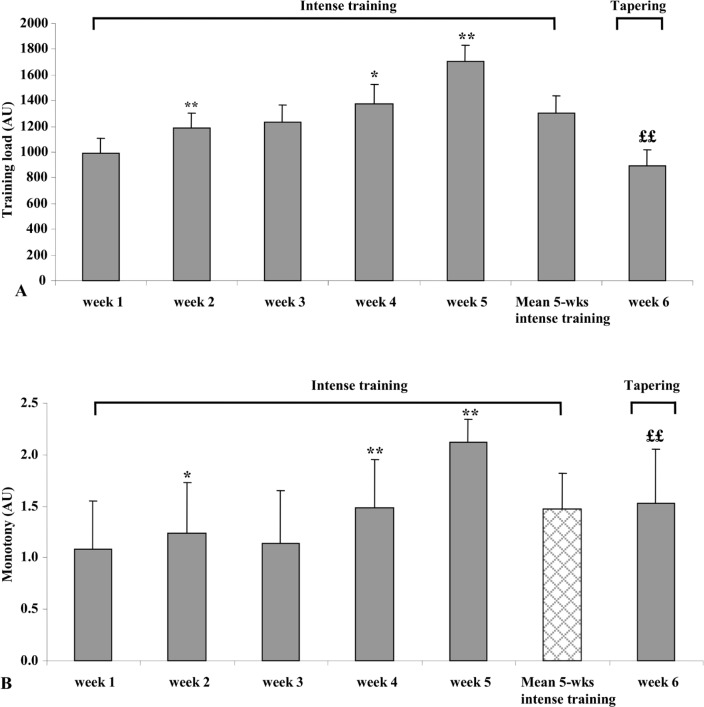

Training load and monotony indexes significantly increased during the intensive period (0.05 < p<0.01) and significantly decreased during the tapering period (p<0.01) (Figure 1). As shown in Table 1, the boxers’ body composition was altered during the whole period, especially the body fat percentage, which decreased at T1 (21.9%, p<0.001, ES = 2.9) and at T2 (25.2%, p<0.001, ES = 0.50).

FIG. 1.

Training loads (A) and monotonies (B) registered during the whole training period (intensive training and tapering periods).

*: superior to the precedent value; * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01

£: inferior to the precedent value; ££ p < 0.01.

The reliability of hand grip (ICC = 0.96, SEM = 0.33) and Yo-Yo IRT1 (ICC = 0.99, SEM = 9.57) were high. The hand grip performance decreased at T1 (-3.1%, p<0.01, ES = 0.42) and increased at T2 (+8.2%, p<0.01, ES = 0.51). Likewise, the Yo-Yo IRT1 distance decreased at T1 (-3.9%, p<0.01, ES = 1.98) and increased at T2 (+8.4%, p<0.01, ES = 1.91).

The plasma cortisol, IGF-1, and IGFBP-3 levels were different for both periods (Table 1). Plasma cortisol levels significantly increased at T1 (+11.3%, p<0.01, ES = 0.38) and significantly decreased at T2 (-10.0%, p<0.01, ES = 0.37). However, plasma IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 levels remained stable at T1 and significantly increased at T2 (+11.6%, p<0.01, ES = 0.46 for plasma IGF-1 and +12.8%, p<0.01, ES = 0.29 for IGFBP-3). The IGF-1/cortisol values significantly increased at T2 (+14.7%, p<0.01, ES = 0.72). No changes were observed in biochemical and anthropometric parameters in control subjects. Likewise, food intake and macronutrient proportions showed no changes throughout the study in both groups.

As summarized in Table 2, the changes in IGF-1/cortisol ratio were correlated with changes in training loads and Yo-Yo IRT1 performance during the training programme. The changes in cortisol, IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 were related to changes in training loads and Yo-Yo IRT1 distance either during the overload period or during the tapering period. At T1, the changes in IGF-1/cortisol ratio were correlated with the percentage changes in Yo-Yo IRT1 distance (r = 0.73, p<0.01) and with the mean training load registered during this intensive training period (r = 0.76, p<0.01). After 1 week of reduced training load, the changes in IGF-1/cortisol ratio was correlated with the percentage changes in Yo-Yo IRT1 distance (r = 0.74, p<0.01) and with the variations of training loads (r = 0.60, p<0.01). Changes in percentage of plasma cortisol levels during the intense period were correlated with the percentage changes in Yo-Yo IRT1 distance (r = 0.78, p<0.001) and the mean training load registered during this intensive period (r = 0.64, p<0.01). However, the percentage change in cortisol was only related to changes in training load registered at T2 (r = 0.65, p<0.01). Finally, the percentage changes in IGFBP-3 and IGF-1 were only correlated with the percentage changes in Yo-Yo R1 distance registered at T1 and T2, respectively (r = 0.51, p<0.05 and r = 0.71, p<0.01, respectively).

TABLE 2.

Correlations between changes in percentage of measured parameters over the intense training (T1 vs T0 = 5 weeks) and the tapering (T2 vs T0 = 1 week) periods in boxers.

| T1 vs T0 | Cortisol | IGF-1 | IGF-1/cortisol | IGFBP-3 | Yo-Yo IRT1 performance | MTL of intense training |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlations | ||||||

| Cortisol | 1 | 0.07 | - | 0.24 | 0.78 ** | 0.64 ** |

| IGF-1 | 1 | - | 0.39 | 0.11 | 0.35 | |

| IGF-1/Cortisol | 1 | 0.13 | 0.73 ** | 0.76 ** | ||

| IGFBP-3 | 1 | 0.51 * | 0.13 | |||

| Yo-Yo IRT1 performance | 1 | 0.41 | ||||

| MTL of intense training | 1 | |||||

| T2 vs T0 | Cortisol | IGF-1 | IGF-1/cortisol | IGFBP-3 | Yo-Yo IRT performance | TL of tapering |

| Correlations | ||||||

| Cortisol | 1 | 0.10 | - | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.65 ** |

| IGF-1 | 1 | - | 0.15 | 0.71 ** | 0.38 | |

| IGF-1/Cortisol | 1 | 0.13 | 0.74 ** | 0.60 ** | ||

| IGFBP-3 | 1 | 0.30 | 0.18 | |||

| Yo-Yo IRT1 performance | 1 | 0.38 | ||||

| TL of tapering | 1 | |||||

Note: IGF-1: insulin-like growth factor-1, IGFBP-3: insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3, MTL: mean of training load, TL: training load.

p < 0.05

p < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

In the present study the variations in IGF-1/cortisol ratio were correlated with both performance and training load variations over the whole training period in the studied young boxers. Moreover, cortisol and IGF-1 variations were also correlated with the changes of performance and training load during the intensive training period and the taper period.

Exercise training is considered as an intense task incorporating both physiological and psychological demands leading to an overall physiological response of the athlete's organism in reaction to stresses. The responses of gonadotropic and corticotropic axes to the stress generated by training have been well documented [6, 2]. The balance between these two hormonal axes is usually assessed by the testosterone/cortisol ratio, which reflects the organism anabolic/catabolic state of the athletes during training [6, 2]. However, both testosterone and cortisol are characterized by pulsatile release and rapid clearance. Accordingly, having a single point of hormonal sampling, without an understanding of the underlying basic pattern, may not provide an accurate depiction of endocrine activity [22, 25]. In this context, the somatotropic or growth hormone-IGF-1 axis may also respond to an imposed training stress. This axis is important and is in relation to the metabolic supply when energetic demand is increased as in sports training and performance. Several investigations have studied the IGF-1, which is a hepatic relay of GH action having a linear production and a longer half life (∼6 h) than GH, also representing an integration of the changes in GH concentrations. Thus, the study of the balance between the corticotropic and the somatotropic axes during training could provide information on the adaptation of the athletes’ organisms during training. Accordingly, Hug et al. [26] have suggested that IGF-1/cortisol ratio might be a useful parameter in the early detection of an imbalance between anabolic and catabolic metabolism in the same way that free testosterone/cortisol ratio might be.

Several studies have examined the effect of training programmes on cortisol levels. They showed that high-intensity exercise training causes an increase of cortisol hormone [27, 7]. This increase supports the catabolic state which may be partially responsible for the observed decrease in physical performances. In the present study, the subjects were deliberately overreached by their coaches by increasing resistance training, endurance and boxing specific skill training workloads over a 5-week period. Training load was progressively increased during the 5-week overload period by increasing training frequency and duration, which led to a reduction in Yo-Yo IRT1 distance, thus reflecting impaired aerobic fitness of the athletes. These results are in agreement with previous research that showed a decrease in physical performance following an increased training load in endurance training athletes [28], swimmers [29] and rugby players [6, 2]. The decreased Yo-Yo IRT1 performance following the 5-week intense training in the present study may be due to a number of physiological and biochemical factors such as reduced muscle glycogen levels, increased muscle damage, or simply acute fatigue diminishing the ability to perform maximal efforts [6]. The relationships found between the variations of cortisol and those of training load and Yo-Yo IRT1 performance during this training period may show that the boxers were in a catabolic state with possible elevated levels of muscle damage when the Yo-Yo IRT1 performance was found to be reduced [2]. Similar conclusions have been previously advanced by Coutts et al. [6] in Australian high level rugby players during 6 weeks of intense training. This catabolic state during the overload training period was confirmed by the lower IGF-1/cortisol ratio. Therefore, this ratio could be considered an indicator of a state of tiredness generated by the increase in training load leading to a possible catabolic state. Indeed, the relationships found between changes in IGF-1/cortisol and the training load and Yo-Yo IRT1 variations confirm this hypothesis.

Conversely, the IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 levels remained unchanged during the overload period. It was reported that circulating IGF-1 and its binding protein IGFBP-3 decrease during intense training programmes [12]. However, Nindl et al. [30] have recently reported unchanged IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 levels despite fitness improvements after eight weeks of resistance, aerobic, and combined exercise training in young healthy women. They concluded that locally produced IGF-1 may be of greater relative importance than endocrine-derived IGF-1. Thus, the unaltered IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 levels observed in the present study during the intense training could be supported by the conclusions of Nindl et al. [30].

The cortisol, IGF-1, IGFBP-3 and IGF-1/cortisol ratio values varied differently during the taper period with respect to the intense training period. The cortisol level decreased and returned to basal values while IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 increased, resulting in a higher IGF-1/cortisol ratio. The return of cortisol levels to basic values observed during this period could represent a homeostasis state [31]. Accordingly, Bonifazi et al. [27] found in elite male swimmers that a decrease in plasma cortisol was related to improvements in performance. In accordance with these findings, we assume that the decrease in cortisol level was associated with an improved Yo-Yo IRT1 performance. In addition, the increase of IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 levels, which reflect the anabolic state generated by the adaptation of the boxers’ organisms during the taper period, confirms this hypothesis. In this context, studies have shown that some physical activity levels that are too intense could cause a prolonged reduction of IGF-1 levels [32, 12, 20] while regular exercise without excessive load, during training, induces chronic increased levels of this hormone [13]. Additionally, some studies have found significant positive correlations between fitness and circulating IGF-1 levels [13, 17]. Such a correlation indicates that fitness and exercise in various populations are associated with increased activity of the somatotropic axis, favouring an anabolic state. Indeed, a relationship between the IGF-1 variations and the Yo-Yo IRT1 performance changes was found during the taper period in the present study. This conclusion was confirmed by an increase of IGF-1/cortisol ratio and the relationship observed between the changes in this ratio and the changes of both training load and Yo-Yo IRT1 distance.

Thus, the IGF-1/cortisol ratio, which may reflect the anabolic/catabolic state of young boxers’ organisms, could be a sensitive marker of training load and physical performance variations. We therefore conclude that IGF-1/cortisol ratio could be considered as a useful and sensitive marker for training monitoring and performance responses. However, further studies are warranted to strengthen the contribution of the IGF-1/cortisol ratio in the monitoring and the follow-up of training in several athletic populations during longer training periods.

CONCLUSIONS

It is concluded that IGF-1/cortisol ratio could be a sensitive marker of training monitoring and physical performance variations. Moreover, this ratio might be a useful indicator of athletes’ organism anabolic/catabolic status helping to prevent possible states of acute fatigue and/or overtraining. Along with the reviews of the literature, these novel findings in boxers provide a new viewpoint for examining, interpreting and utilizing hormones in sport science research and practice, with possible implications and applications for understanding and improving human health and sport performance.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was financially supported by the Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research in Tunisia. The authors would like to thank the coaches and boxers for their cooperation.

Conflict of interests

The authors declared no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hall CJ, Lane AM. Effects of rapid weight loss on mood and performance among amateur boxers. Br J Sports Med. 2001;35:390–395. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.35.6.390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elloumi M, Ben Ounis O, Tabka Z, Van Praagh E, Michaux O, Lac G. Psychoendocrine and physical performance responses in male Tunisian rugby players during an international competitive season. Aggress Behav. 2008;34:623–632. doi: 10.1002/ab.20276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Foster C, Florhaug JA, Franklin J, Gottschall L, Hrovatin LA, Parker S, Doleshal P, Dodge C. A new approach to monitoring exercise training. J Strength Cond Re. 2001;15:109–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manzi V, D'Ottavio S, Impellizzeri FM, Chaouachi A, Chamari K, Castagna C. Profile of weekly training load in elite male professional basketball players. J Strength Cond Re. 2010;24:1399–1406. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181d7552a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bangsbo J, Mohr M, Krustrup P. Physical and metabolic demands of training and match-play in the elite football player. J Sports Sci. 2006;24:665–674. doi: 10.1080/02640410500482529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coutts A, Reaburn P, Piva TJ, Murphy A. Changes in selected biochemical, muscular strength, power, and endurance measures during deliberate overreaching and tapering in rugby league players. Int J Sports Med. 2007;28:116–124. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-924145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Filaire E, Bernain X, Sagnol M, Lac G. Preliminary results on mood state, salivary testosterone/cortisol ratio and team performance in a professional soccer team. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2001;86:179–184. doi: 10.1007/s004210100512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gomes RV, Moreira A, Lodo L, Nosaka K, Coutts AJ, Aoki MS. Monitoring training loads, stress, immune-endocrine responses and performance in tennis players. Biol Sport. 2013;30:173–80. doi: 10.5604/20831862.1059169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kanaley JA, Weltman JY, Pieper KS, Weltman A, Hartman ML. Cortisol and growth hormone responses to exercise at different times of day. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:2881–2889. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.6.7566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Staron RS, Karapondo DL, Kraemer WJ, Fry AC, Gordon SE, Falkel JE, Hagerman FC, Hikida RS. Skeletal muscle adaptation during early phase of heavy-resistance training in men and women. J Appl Physiol. 1994;76:1247–1255. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.76.3.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Degoutte F, Jouanel P, Bègue RJ. Food restriction, performance, biochemical, psychological, and endocrine changes in judo athlete. Int J Sports Med. 2006;27:9–18. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-837505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Filaire E, Jouanel P, Colombier M, Bégue RJ, Lac G. Effects of 16 weeks of training prior to a major competition on hormonal and biochemical parameters in young elite gymnasts. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;16:741–750. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2003.16.5.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eliakim A, Scheett TP, Newcomb R, Mohan S, Cooper DM. Fitness, training, and the growth hormone --> insulin-like growth factor I axis in prepubertal girls. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:2797–2802. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.6.7560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwarz AJ, Brasel JA, Hintz RL, Mohan S, Cooper DM. Acute effects of brief low-and-high intensity exercise on circulation insulin-like growth factor (IGF) I, II and IGF-binding protein-3 and its proteolysis in young healthy men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:3492–3497. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.10.8855791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chaari H, Zouch M, Denguezli M, Bouagina E, Zouali M, Tabka Z. A high level of volleyball practice enhances bone formation markers and hormones in prepubescent boys. Biol Sport. 2012;29:303–309. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nebigh A, Rebai H, Elloumi M, Bahlous A, Zouch M, Zaouali M, Alexandre C, Sellami S, Tabka Z. Bone mineral density of young boy soccer players at different pubertal stages: relationships with hormonal concentration. Joint Bone Spine. 2009;76:63–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manetta J, Brun JF, Maimoun L, Callis A, Préfaut C, Mercier J. Effect of training on the GH/IGF-I axis during exercise in middle-aged men: relation to glucose homeostasis. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2002;283:929–936. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00539.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tanner JM, Whitehouse RH, Takaishi M. Standards from birth to maturity for height, weight, height velocity, and weight velocity: British children 1965 II. Archive Disease in Childhood. 1966;41:613–635. doi: 10.1136/adc.41.220.613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Slaughter MH, Lohman TG, Boileau RA, Horswill CA, Stillman RJ, Van Loan MD, Bemben DA. Skinfold equation for estimation of body fatness in children 399 and youth. Hum Biol. 1988;60:709–723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elloumi M, El Elj N, Zaouali M, Maso F, Filaire E, Tabka Z, Lac G. IGFBP-3, a sensitive marker of physical training and overtraining. Br J Sports Med. 2005;39:604–610. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2004.014183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haddad MAC, Castagna C, Hue O, Wonge DP, Tabben M, Behm DG, Chamari K. Validity and psychometric evaluation of the French version of RPE scale in young fit males when monitoring training loads. Sci sports. 2013;28:29–35. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krustrup P, Mohr M, Amstrup T, Rysgaard T, Johansen J, Steensberg A, Pedersen PK, Bangsbo J. The Yo-Yo intermittent recovery test: Physiological response, reliability, and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35:697–705. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000058441.94520.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Foster C, Daines E, Hector L, Snyder AC, Welsh R. Athletic performance in relation to training load. Wis Med J. 1996;95:370–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Science. 2nd ed. NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. Hillsdale. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Veldhuis J, Keenan DM, Pincus SM. Motivations and methods for analyzing pulsatile hormone secretion. Endocrine Reviews. 2008;29:823–864. doi: 10.1210/er.2008-0005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hug M, Mullis PE, Vogt M, Ventura N, Hoppeler H. Training modalities: over-reaching and over-training in athletes, including a study of the role of hormones. Best Practice and Research. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;17:191–209. doi: 10.1016/s1521-690x(02)00104-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bonifazi M, Sardella F, Lupo C. Preparatory versus main competitions: difference in performances, lactate responses of serum hormones and pre-competition plasma cortisol concentrations in elite male swimmers. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2000;82:368–373. doi: 10.1007/s004210000230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Halson SL, Bridge MW, Meeusen R, Busschaert B, Gleeson M, Jones DA, Jeukendrup AE. Time course of performance changes and fatigue markers during intensified training in cyclists. J Appl Physiol. 2002;93:947–956. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01164.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Atlaoui D, Duclos M, Gouarne C, Lacoste L, Barale F, Chatard JC. The 24-h urinary cortisol/cortisone ratio for monitoring training in elite swimmers. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36:218–224. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000113481.03944.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nindl BC, Alemany JA, Tuckow AP, Rarick KR, Staab JS, Kraemer WJ, Maresh CM, Spiering BA, Hatfield DL, Flyvbjerg A, Frystyk J. Circulating bioactive and immunoreactive IGF-1 remain stable despite fitness improvements after 8 weeks of resistance, aerobic and combined exercise training. J Appl Physiol. 2010;109:112–120. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00025.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elloumi M, Maso F, Michaux O, Robert A, Lac G. Behavior of saliva cortisol (C), testosterone (T) and the T/C ratio during a rugby match and during the post-competition recovery days. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2003;90:23–28. doi: 10.1007/s00421-003-0868-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosendal L, Langberg H, Flyvbjerg A, Frystyk J, Ørskov H, Kjaer M. Physical capacity influences the response of insulin-like growth factor and its binding proteins to training. J Appl Physiol. 2002;93:1669–1675. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00145.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]