Abstract

Inflammasomes are multi-protein signaling complexes that trigger the activation of inflammatory caspases and the maturation of interleukin-1β. Among various inflammasome complexes, the NLRP3 inflammasome is best characterized and has been linked with various human autoinflammatory and autoimmune diseases. Thus, the NLRP3 inflammasome may be a promising target for anti-inflammatory therapies. In this review, we summarize the current understanding of the mechanisms by which the NLRP3 inflammasome is activated in the cytosol. We also describe the binding partners of NLRP3 inflammasome complexes activating or inhibiting the inflammasome assembly. Our knowledge of the mechanisms regulating NLRP3 inflammasome signaling and how these influence inflammatory responses offers further insight into potential therapeutic strategies to treat inflammatory diseases associated with dysregulation of the NLRP3 inflammasome.

Keywords: inflammasome, inflammation, interaction, mechanism, NLRP3

Introduction

The inflammasome was described a decade ago as a large intracellular signaling platform that contains a cytosolic pattern recognition receptor, especially a nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor (NLR) or an absent in melanoma 2 (AIM2)-like receptor. Among NLR inflammasome complexes, the NLRP3 inflammasome has been the most widely characterized and is a crucial signaling node that controls the maturation of two proinflammatory interleukin (IL)-1 family cytokines: IL-1β and IL-18.1,2,3 Activation of the pattern recognition receptor NLRP3 leads to recruitment of the adapter apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a C-terminal caspase recruitment domain (ASC), resulting in the activation of pro-caspase-1 into its cleaved form.1 Caspase-1 is known as an inflammatory caspase that plays a role in the maturation of IL-1β and IL-18 into active cytokines and the initiation of pyroptosis by autocatalysis and activation.4

Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome is thought be regulated at both the transcriptional and post-translational levels. The first signal in inflammasome activation involves the priming signal, induced by the toll-like receptor (TLR)/nuclear factor (NF)-κB pathway, to upregulate the expression of NLRP3, the level of which is otherwise relatively low in numerous cell types.5,6 Signal 2 is transduced by various pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) to activate the functional NLRP3 inflammasome by initiating assembly of a multi-protein complex consisting of NLRP3, the adaptor protein ASC, and pro-caspase-1. Several molecular mechanisms have been suggested for NLRP3 activation to induce caspase-1 activation and IL-1β maturation. These include pore formation and potassium (K+) efflux,7,8 lysosomal destabilization and rupture,9,10 and mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation.10,11,12

Evidence supports that the aberrant activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome is associated with the pathogenesis of various autoinflammatory, autoimmune, and chronic inflammatory and metabolic diseases, including gout, atherosclerosis, and type 2 diabetes.13,14,15 Thus, activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome should be tightly regulated to prevent unwanted host damage and excessive inflammation. To date, several regulatory mechanisms and binding partners have been described in NLRP3 inflammasome activation. In this review, we focus on the molecular mechanisms that activate and regulate excessive NLRP3 inflammasome activation.

Overview of the NLRP3 Inflammasome Complex

NLRs are innate cytosolic receptors that recognize diverse PAMPs and DAMPs. Among the NLRs, several members including NLRP1, NLRP2, NLRP3, NLRC4, NLRP6, NLRP7, and NLRP12 are able to form multimeric inflammasome complexes.16 NLRP3 (also known as cryopyrin and NALP3) is the best characterized inflammasome and is expressed mainly by myeloid lineage cells. NLRP3 is inducible by stimulation of TLR activation, cytokine stimulation, and other signals.17 The canonical NLRP3 inflammasome complex is an intracellular protein complex consisting of the sensor NLRP3, the adaptor ASC, and pro-caspase-1. The Nlrp3 (CIAS1) gene encodes a protein containing an amino-terminal pyrin domain, a central nucleotide-binding domain, and a C-terminal leucine-rich repeat (LRR) motif.18 After sensing danger signals, presumably via the LRR domain of NLRP3, NLRP3 monomers induce oligomerization and interact with the pyrin domain (PYD) domain of ASC through homophilic interactions.3 The adaptor ASC then recruits the cysteine protease pro-caspase-1 via a caspase recruitment domain (CARD).3 The resulting autocatalysis and activation of caspase-1 lead to maturation and secretion of proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18 and, under certain conditions, to induction of pyroptosis, a form of programmed inflammatory cell death.19,20,21 Recent structural studies have revealed that two successive steps in nucleation-induced and ‘prion-like' polymerization — i.e., NLRP3 nucleation of the PYD filaments of ASC and the clustering of pro-caspase-1 within star-like fibers of ASC — are essentially required for the proximity-induced activation of inflammasomes.22,23

NLRP3 also interacts with NOD2, which plays a non-redundant role in the processing of pro-IL-1β, in a CARD-independent manner.24 It has also been shown that both NOD2 and NLRP3 play roles in MDP-induced IL-1β release in macrophages.25 In non-canonical activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, cytosolic detection of lipopolysaccharides (LPS) activates caspase-11, which promotes susceptibility to endotoxin-induced sepsis even in Tlr4(-/-) mice.26,27 Recently, a noncanonical role of NLRP3 has been revealed in T helper type 2 cells as a critical transcriptional factor in T helper 2 differentiation through binding to the Il4 promoter and transactivation of its promoter activity.28 IL-1β is a key proinflammatory cytokine that affects nearly every cell type and mediates inflammation in a variety of tissues; thus, it is involved in various systemic inflammatory diseases, marked by recurrent fevers, leukocytosis, and elevated acute phase proteins.29,30 Additionally, IL-1β levels and activities are highly associated with the pathogenesis of various autoinflammatory and autoimmune diseases.30,31 Unlike other cytokines, the IL-1 family appears to have unique properties because it is also involved in the suppression of inflammation and subsequent direction of adaptive immune responses.31

Ligands/Stimuli that Activate the NLRP3 Inflammasome Complex

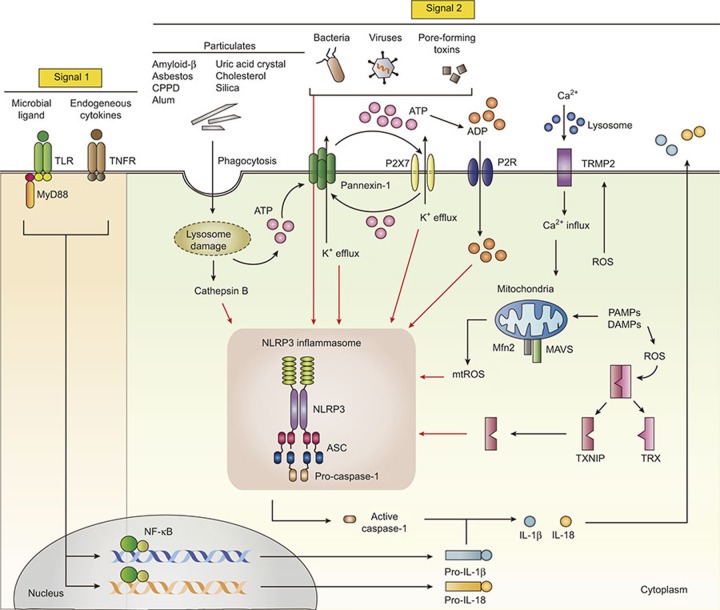

To date, it has been accepted that activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome depends on two signals: a priming signal, required for the upregulation of NLRP3 and pro-IL-1β, and a second signal that triggers assembly into the NLRP3 inflammasome complex.21,32,33 NLRP3 responds to many stimuli for activation of the inflammasome.34 The NLRP3 inflammasome is activated by a variety of PAMPs and DAMPs, originating from numerous pathogens, a large number of pore-forming toxins, adenosine triphosphate (ATP), and particulate crystals and aggregates.34,35 Various bacterial and viral pathogens and their components that activate the NLRP3 inflammasome complex have been summarized extensively in previous reviews.35,36,37,38,39 The general mechanisms by which NLRP3 inflammasome is activated are summarized in Figure 1. Thus, we briefly review previous works on bacterial and viral infections associated with NLRP3 inflammasome activation.

Figure 1.

Both signal 1 and signal 2 are required for NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome requires at least two signals: signal 1, also known as the priming signal, is mediated by microbial ligands recognized by TLRs or cytokines such as TNF-α. Signal 1 activates the NF-κB pathway, leading to upregulation of pro-IL-1β and NLRP3 protein levels. The signal 2 is mediated by numerous PAMP or DAMP stimulation, and promotes the assembly of ASC and pro-caspase-1, leading to activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome complex. Under noninfectious conditions, extracellular ATP and K+ efflux leads to the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome via the P2X7 receptor and pannexin-1. Various endogenous and exogenous particulates, including MSU crystals, CPPD crystals, cholesterol crystals, amyloid β, silica crystals, asbestos, and alum, promote lysosomal damage and release cathepsin B into the cytosol, leading to the NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Particulate matters (uric acid, silica, and alum) are also able to trigger inflammasome assembly through multiple purinergic receptor signaling. Additionally, calcium influx through TRPM2 activates NLRP3 inflammasome through mitochondrial ROS. Dissociated TXNIP, which is triggered by intracellular ROS, also activates the NLRP3 inflammasome. ADP, adenosine diphosphate; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; K+, potassium; ASC, apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a C-terminal caspase recruitment domain; CPPD, calcium pyrophosphate dehydrate; DAMPs, damage-associated molecular patterns; NLRP3, NACHT, LRR, and PYD domains-containing protein 3; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; P2X7, P2X purinoceptor 7; P2R, purinergic receptor; PAMPs, pathogen-associated molecular patterns; ROS, reactive oxygen species; TLRs, toll-like receptors; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α TXNIP, thioredoxin (TRX)-interacting protein.

PAMP signals that activate the NLRP3 inflammasome

The NLRP3 inflammasome is activated by numerous bacterial pathogens including Staphylococcus aureus, Group B Streptococcus, Listeria monocytogenes, and Neisseria gonorrhoeae.40,41,42 Viral nucleic acids are usually detected by the retinoic acid-inducible gene 1 and AIM2-like receptor (ALR) inflammasomes; however, several viruses and their components, including influenza virus (the proton-selective ion channel protein M2),43 encephalomyocarditis virus (viroporin 2B),44 poliovirus and enterovirus 71 (non-structural 2B protein),44 rhinovirus (2B proteins),45 human respiratory syncytial virus (small hydrophobic protein),46 are sufficient to stimulate NLRP inflammasome activation. Recent studies have revealed a crucial protective role of inflammasome activation during viral infection, via an increase in adaptive immune activation with limited tissue damage.47,48 NLRP3 itself was not required, whereas ASC and caspase-1 were essential for the activation of adaptive and protective immunity against flu challenge.48 Furthermore, the inhibitory roles of bacterial and viral pathogens upon NLRP3 inflammasome activation have also been reported in terms of the evasion mechanisms of many pathogens from host defenses, although the details of these mechanisms are beyond the scope of this review.

DAMP signals and environmental stimuli triggering the NLRP3 inflammasome

Sensing a danger signal is an important physiological role of the NLRP3 inflammasome; various DAMP signals have been reported to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome.49 Extracellular ATP is a well-known endogenous danger signal and widely used for canonical activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome.40 Recent studies have shown that cell stress in NLRP3 inflammasome-associated autoinflammatory disease enhanced ATP release and maintained high levels of IL-1β and IL-18 in blood monocytes.50 Nanoparticle-induced ATP release activates the NLRP3 inflammasome through interaction with adenosine receptors as well as cellular uptake by nucleoside transporters.51 However, ATP-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation is differentially regulated between dendritic cells and macrophages. In dendritic cells, stimulation with TLR ligands in the absence of ATP stimulation was sufficient to produce mature IL-1β.52

Additionally, gout-associated etiologic agents, such as uric acid crystals and calcium pyrophosphate dehydrate (CPPD) crystals, can lead to the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome and production of IL-1β and IL-18.53 Endogenous triggering by the glycosaminoglycan hyaluronan, an important component of the extracellular matrix,54 and amyloid-β fibrils55 activates the NLRP3 inflammasome, thus linking them to inflammatory disease and tissue damage. Environmental crystalline structures, including silica, asbestos, aluminum salt crystals,56,57 and the adjuvant aluminum hydroxide,58 are also able to trigger NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Moreover, an adjuvant-free, allergic lung inflammation induced by ovalbumin requires the NLRP3 inflammasome activation.59 Ultraviolet irradiation activates the NLRP3 inflammasome in keratinocytes60 and ultraviolet B-induced caspase-4 is required for efficient NLRP3 inflammasome activation through interaction with and activation of caspase-1 in macrophages.61 Recent studies showed that albumin triggers NLRP3 inflammasome activation in renal proximal tubular cells and downregulates tight junction proteins at the gene and protein levels, affecting renal tubular integrity.62

Dietary intake of fatty acids and cellular lipid metabolism are associated with regulation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Previous studies showed that dietary saturated fatty acids induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation63 and enhanced IL-1β-induced adipocyte inflammation, leading to insulin resistance.64 Monounsaturated fatty acids in high-fat diets decrease IL-1β secretion and increase insulin sensitivity.65 Recently, mitochondrial uncoupling protein-2 (UCP2), an essential inducer of fatty acid synthase, has been shown to regulate NLRP3 inflammasome activation through stimulation of lipid synthesis. Importantly, UCP-2-deficient mice showed improved survival after polymicrobial sepsis and decreased lipid synthesis and secretion of IL-1β and IL-18 after LPS challenge.66 Considerable efforts have focused on identifying agonists of NLRP3 inflammasome activation as well as determining the molecular mechanisms by which diverse agonists induce the assembly of inflammasome components.

Molecular Mechanisms of the Canonical Activation of the NLRP3 Inflammasome

Because of the vast number and diversity of NLRP3 stimuli known to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome, it seems unlikely that they all bind to the NLRP3 structure to activate the inflammasome. Thus, a major outstanding question in the field relates to the exact molecular mechanism underlying activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. In this chapter, we discuss three generally accepted mechanisms regarding activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome complex.

ROS signaling in NLRP3 inflammasome complex activation

For NLRP3 inflammasome activation, several mechanisms and/or pathways have been proposed. The mitochondria are the main intracellular organelles that contribute the most to cellular ROS.67 Previous studies showed that ROS, especially those from mitochondria, contributed to activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome.10,12,68,69,70 Indeed, numerous NLRP3 inflammasome activators are known to trigger mitochondrial ROS production in a variety of cells. For example, the saturated fatty acid palmitate leads to the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome and release of active IL-1β in a mitochondrial ROS-dependent manner.63 Moreover, multiple NLRP3-triggering agents leading to mitochondrial dysfunction and cell death result in the cytosolic increase of oxidized mitochondrial DNA, which, in turn, appears to bind to NLRP3 and to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome complex.71 However, both mitochondrial ROS-dependent and -independent pathways are required for NLRP3 inflammasome activation triggered by serum amyloid A.72 Another recent study suggested that ROS-dependent and -independent NLRP3 activators cause mitochondrial destabilization and dysfunction, thereby promoting NLRP3 inflammasome activation.73 Moreover, liposome-mediated inflammasome activation is dependent on the generation of mitochondrial ROS, and ROS-dependent calcium influx via the TRPM2 channel.74

In addition to mitochondrial respiration, intracellular ROS are generated through a variety of enzymes, including nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidases (NOX), xanthine oxidase, and oxygenase.75,76,77 Earlier studies showed that NOX-induced ROS generation was key for activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome upon triggering by ATP or particle phagocytosis.56,78,79 Currently, it is unclear whether NOX-derived ROS are required for NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Several studies demonstrated that caspase-1 activation and IL-1β secretion are not affected, and may even be increased, in phagocyte oxidase-defective monocytes in chronic granulomatous disease.80,81,82 Moreover, macrophages from NOX2-deficient mice dose not fail in the maturation and secretion of IL-1β in response to various signals, including silica crystals, monosodium urate (MSU), ATP, and deoxyadenylic-deoxythymidylic.57 In superoxide dismutase 1-deficient macrophages and in vivo, increased superoxide generation inhibits caspase-1 activation and cytokine production.83 Furthermore, ROS are required for the priming step by proinflammatory signals, but not for activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome.84

Recent studies have revealed that xanthine oxidase-derived ROS play a role in IL-1β release and caspase-1 secretion in macrophages during NLRP3 inflammasome activation.85 Much progress has been made in the elucidation of ROS involvement in the regulation of NLRP3 inflammasome activation.85 However, it is also clear that more work is needed to understand how ROS from different sources differentially regulate inflammasome activation.

Potassium efflux and activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome

Another well-established mechanism of NLRP3 inflammasome activation is a decrease in the intracellular K+ concentration. It was previously shown that the common NLRP3 activators ATP and nigericin cause a non-selective conductance of K+ across the cell membrane and the alteration of intracellular ionic contents, for the initiation of pro-IL-1β processing.7 Furthermore, a reduction in intracellular K+ levels was found to be essential for NLRP3 inflammasome activation in monocytes/macrophages when triggered by numerous known NLRP3 activators, including the pore-forming toxin nigericin, P2X purinoceptor 7 (P2X7) stimulation by ATP, or bacterial infection with live Escherichia coli.8 Additionally, S. aureus hemolysins in the presence of lipoproteins are able to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome via K+ efflux.86 It is also known that the NLRP1 inflammasome activator anthrax lethal toxin of Bacillus anthracis depends on low intracellular K+ for IL-1β maturation and inflammasome activation.8 Currently, a reduction in intracellular K+ concentration is thought to be a common pathway for NLRP3 inflammasome complex activation, triggered by numerous NLRP3 signals, including bacterial toxins and phagocytosis of particulate matter.87

Both mitochondrial ROS and K+ efflux, induced by various NLRP3 activators, appear to contribute together to activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, leading to caspase-1 activation and IL-1β maturation. Candida albicans and its components, the secreted aspartic proteases, and Aspergillus hyphae activate the NLRP3 inflammasome, and this is mediated through pathways involving both ROS generation and K+ efflux.88,89,90 In a study on the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis, hydroxyapatite crystals stimulated NLRP3 inflammasome activation through multiple pathways: ROS generation, lysosomal damage, and K+ efflux.91 Additionally, the anthracycline doxorubicin induces systemic inflammation associated with IL-1β release, mediated by NLRP3 inflammasome activation, which is controlled by co-treatment with ROS inhibitors or by cultivation of cells with high levels of extracellular K+.92

Lysosomal destabilization and activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome

In addition to ROS and K+ efflux, disruption of the lysosomal membrane, caused by phagocytosis of particulate matter or live pathogens or by sterile lysosomal damage (without crystals), results in NLRP3 activation.55,57 In agreement with this, proton pump inhibitors (used for neutralization of lysosomal pH) or blockade of cathepsin(s) significantly inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome activation.57,93 Indeed, various PAMPs and DAMPs seem to be dependent on lysosomal destabilization for triggering NLRP3 inflammasome activation. For example, disruption of lysosomal membranes and cathepsin B release are required for NLRP3 inflammasome activation by adenovirus type 5, through penetration of endosomal membranes.94 Group B Streptococcus-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation also depends on hemolysin-mediated lysosomal leakage.95 Recently, lysosomal rupture and the release of lysosomal hydrolases have been shown to be essential for albumin-triggered tubulointerstitial inflammation and fibrosis, implicating lysosomal damage in the pathogenesis of chronic kidney disease through NLRP3 inflammasome activation.96

Earlier studies showed that rapid cell death induced by disease-associated CIAS1 mutations was significantly inhibited by the cathepsin B-specific inhibitor CA-074-Me.97 Moreover, caspase-1 activation during pyroptosis, a programmed cell death pathway, leads to increased membrane permeability and calcium influx, resulting in lysosomal exocytosis and lysosomal protein secretion.98 The lysosome-destabilizing agents Leu-Leu-OMe and alum induce lysosomal rupture and release of lysosomal hydrolases prior to cell death. However, lysosomal rupture is a late event after NLRP3 inflammasome activation in response to prototypical pyroptosis inducers, such as nigericin and ATP.99

Previous studies also reported that lipid-stressed macrophages primed with LPS show lysosomal dysfunction, lysosomal membrane damage, and cathepsin release.100,101 It was shown that phagolysosomal damage was required for cholesterol crystal-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation.102 In addition, cholesterol crystal-induced IL-1β release was reduced in mice deficient in cathepsins B or L.102 In palmitate-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation, lysosomal protease cathepsin B is required for IL-1β release (signal 2), whereas the lysosomal calcium pathway is essential for production of pro-IL-1β levels through stabilization of IL-1β mRNA.101 Thus, the lysosome plays an essential role in both the priming and assembly phases of the lipotoxic inflammasome.101

By activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome complex, several molecular pathways in response to various PAMPs and DAMPs are interconnected. Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome by nigericin leads to mitochondrial ROS generation, subsequently causing lysosomal membrane permeabilization.101 Recent studies showed that sustained zinc depletion leads to lysosome damage, acting as a stimulus for NLRP3 inflammasome activation.103 Additional mechanism by which lysosomal rupture activates the NLRP3 inflammasome complex has been demonstrated in macrophages.9 The TAK1-JNK pathway, which is also modulated by calcium-dependent calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase type II function, is activated through lysosomal rupture and is required for the complete activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome.9 Although we discuss here common mechanisms, i.e., ROS signaling,62 K+ efflux,82 and lysosomal destabilization,55 in terms of NLRP3 inflammasome activation, other pathways, such as purinergic receptor signaling,104 are being revealed to explain the mechanisms by which diverse stimuli activate the NLRP3 inflammasome complex (Figure 1).

Spatial arrangement of intracellular organelles for activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome

Several lines of evidence indicate that the spatial arrangement of intracellular organelles is important for NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Earlier findings revealed that inflammasome activation triggers the redistribution of both NLRP3 and the adaptor ASC in the perinuclear space, where the endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria organelle clusters are co-localized. Previous studies showed that inflammasome stimuli caused a drop in intracellular coenzyme NAD(+) levels, thus inactivating the deacetylase sirtuin 2, to promote accumulation of acetylated α-tubulin, which, in turn, results in dynein-dependent transport of mitochondria. Subsequently, the microtubule-driven apposition of ASC on mitochondria to NLRP3 on the endoplasmic reticulum contributes to NLRP3 inflammasome activation.105 As described below, the mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein (MAVS) adaptor and its small heterodimer partner are required for recruitment of NLRP3 to mitochondria, although the two molecules function in opposite manners.106 The mitochondrial protein MAVS contributes to NLRP3 inflammasome activation,106 whereas small heterodimer partner (SHP) functions as a fine tuner and negatively regulates NLRP3 inflammasome activation.107 SHP deficiency results in the close proximity of NLRP3 and ASC in the endoplasmic reticulum, in cases in which the optimal sites (mitochondrial structures) for inflammasome activation.107 These recent findings suggest that the mitochondria-associated membrane (MAM) structure — the physiological interaction between the endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria — is critical for various biological functions including inflammasome activation.108

Recently, resveratrol, a natural polyphenol, was shown to suppress the assembly of ASC and NLRP3 by inhibition of the acetylated α-tubulin-mediated spatial arrangement of mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum, resulting in decreased NLRP3 inflammasome activation.109 Moreover, when at least two NLRs are activated (e.g., by Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium), NLRC4 and NLRP3 are simultaneously present in a single inflammasome complex in macrophages to drive IL-1β processing.109 Further studies regarding the detailed mechanisms responsible for the spatial localization of different components are needed to understand how different members of the NLR family and their adaptors cooperate together to activate the entire inflammasome complex.

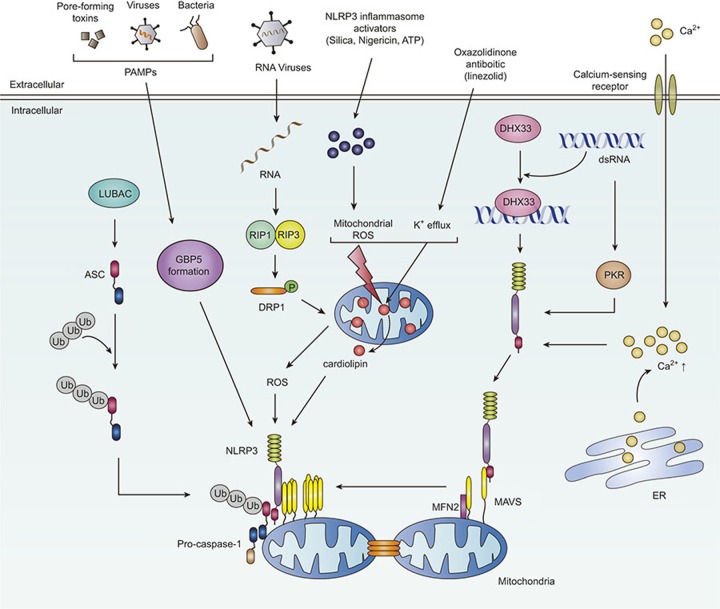

Adaptors/Molecules Involved in Activation of the NLRP3 Inflammasome Complex

As discussed above, the exact molecular mechanisms of NLRP3 inflammasome complex organization have not been determined. Emerging evidence indicates that several molecules/adapters other than ASC are also involved in the interaction and activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome complex. Earlier studies showed that thioredoxin (TRX)-interacting protein (TXNIP) linked to NLRP3 is required for inflammasome activation and insulin resistance.110 In the resting state, TXNIP binds to TRX; NLRP3 inflammasome stimuli such as uric acid crystals result in dissociation of TXNIP from TRX, allowing it to bind NLRP3. The association of TXNIP with NLRP3 inflammasome activation is thought to be important in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes.110 In addition, MAVS, which interacts with NLRP3, participates in NLRP3 inflammasome function as an interacting partner. Indeed, MAVS is required for NLRP3 recruitment to mitochondria and the production of IL-1β.106

It has also been shown that guanylate-binding protein (GBP) 5, a member of the interferon-inducible GBP family, binds to the pyrin domain of NLRP3 and serves as an activator of selected NLRP3 inflammasomes, especially in response to soluble agents or Salmonella typhimurium, but not crystalline agents or double-stranded DNA.111 Recently, HOIL-1L, a component of linear ubiquitination assembly complex (LUBAC), was found to be an essential activator of NLRP3/ASC inflammasome assembly through linear ubiquitination of ASC, a novel LUBAC substrate.112 Additionally, the direct binding of NLRP3 to the mitochondrial lipid cardiolipin is important for NLRP3 inflammasome activation in response to both ROS-dependent and -independent activators. 73

Recent studies showed that DHX33, a member of the DExD/H-box helicase family, plays a role in activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome through interaction with NLRP3. DHX33 binds to double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) as a cytosolic RNA sensor and is essential for the secretion of IL-18 and IL-1β from human macrophages stimulated with cytosolic dsRNA and bacterial/viral RNA.113 Additionally, dsRNA-dependent protein kinase (PKR, also known as EIF2AK2) is an interacting partner of NLRP3 and important for inflammasome activation in response to dsRNA, ATP, MSU, the adjuvant alum, rotenone, live E. coli, and S. typhimurium.114 Moreover, a model of calcium-sensing receptor-mediated NLRP3 inflammasome activation has been proposed.115 In this model, Lee et al. reported that the calcium-sensing receptor activates NLRP3 inflammasome through an increase of intracellular calcium, and even activates spontaneous inflammasome activity in the cells of patients with cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome.115

Moreover, the interaction of NLRP3 with mitofusin 2, a mediator of mitochondrial fusion, is required for NLRP3 inflammasome activation after infection with RNA viruses, including influenza and encephalomyocarditis virus.116 A specific role for the serine-threonine kinases RIP1 (RIPK1) and RIP3 (RIPK3) has been recently reported recently in the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome complex during infection with RNA viruses.117 RNA viral infection triggers the assembly of the RIP1–RIP3 complex, which, in turn, activates the GTPase DRP1 and its translocation to mitochondria, resulting in mitochondrial damage and NLRP3 inflammasome activation.117 A detailed discussion of NLRP3 inflammasome activators has been provided in a recent review.118 Currently identified interacting partners for NLRP3 inflammasome activation and a model of its assembly are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Schematic models of the identified interacting partners for the assembly of NLRP3 inflammasome complex. In response to soluble agents or Salmonella infection, GBP5 is essentially involved in the triggering of the NLRP3 inflammasome activation through binding to the pyrin domain of NLRP3. During RNA viral infection, the GTPase DRP1 and its translocation to mitochondria, resulting in NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Another NLRP3 interacting protein DHX33 can bind to dsRNA as a cytosolic RNA sensor, leading to activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. dsRNA-dependent protein kinase (PKR) is an interacting partner of NLRP3 and activates inflammasome complex. MAVS, a well-known mitochondrial protein and an interacting partner to NLRP3, also mediates NLRP3 mitochondrial localization and inflammasome activation. Cardiolipin binding to NLRP3 is also critical for ROS-dependent and -independent activation of NLRP3 inflammasome complex. In addition, LUBAC is involved in the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome complex through linear ubiquitination of ASC. Calcium-sensing receptors are also important for the promotion of NLRP3 inflammasome assembly through an increase of calcium influx. The interaction of NLRP3 with mitofusin 2 is required for NLRP3 inflammasome activation during RNA virus infection. NLRP3, NACHT, LRR, and PYD domains-containing protein 3; ASC, apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a C-terminal caspase recruitment domain; DAMPs, damage-associated molecular patterns; DHX33, DEAH box polypeptide 33; DRP1, dynamin-1-like protein; GBP5, guanylate binding protein 5; K+, potassium; LUBAC, linear ubiquitination assembly complex; MAM, mitochondria-associated membrane; MAVS, mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein; PAMPs, pathogen-associated molecular patterns; PKR, protein kinase R; RIP, receptor-interacting serine/threonine-protein kinase; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

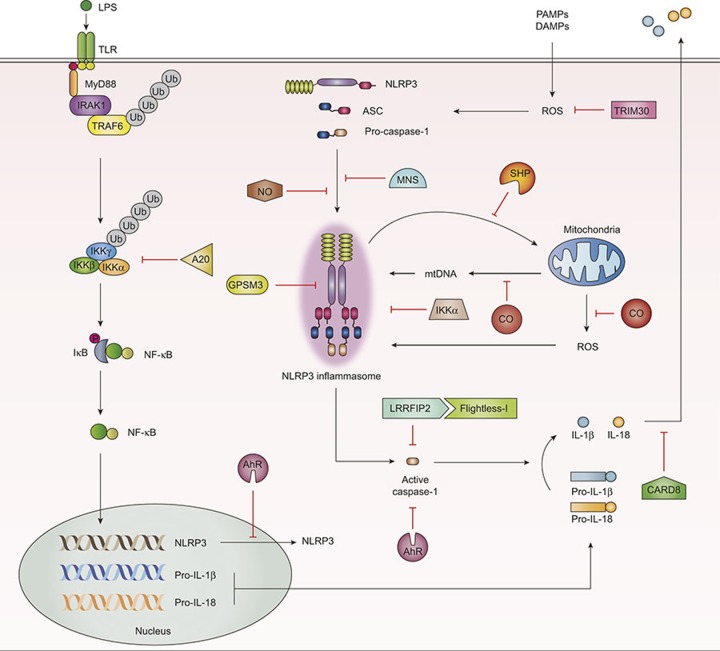

Negative Regulation of NLRP3 Inflammasome Complex Activation

Negative regulation of NLRP3 inflammasome activation is necessary for maintenance of appropriate induction of inflammasome function and for preventing a potentially harmful reaction to the host. Earlier studies showed that tripartite-motif protein 30 (TRIM30) is a negative regulator of NLRP3 inflammasome activation in response to ATP, nigericin, MSU, and silica, through modulation of ROS production, even though TRIM30 did not interact with any component of the NLRP3 inflammasome complex.119 Nitric oxide, a small molecule synthesized by numerous cell types and tissues, inhibits NLRP3-mediated ASC pyroptosome formation and IL-1β secretion through stabilization of mitochondria.120 Additionally, carbon monoxide (CO), a gaseous molecule produced during heme catabolism, plays a role as an inhibitor of NLRP3-induced caspase-1 activation and the secretion of IL-1β and IL-18. It has been found that CO inhibits the generation of mitochondrial ROS, mitochondrial membrane potential, and the cytosolic translocation of mitochondrial DNA in macrophages in response to LPS and ATP.121

The adaptor protein caspase recruitment domain-containing protein 8 (CARD8) interacts with NLRP3 and inhibits IL-1β secretion during NLRP3 inflammasome activation. However, CARD8 is unable to bind to mutant NLRP3 associated with cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome (CAPS), suggesting that it is relevant to the pathogenesis of CAPS.122 Notably, A20, a well-known negative regulator of NF-κB signaling, was found to inhibit NLRP3 inflammasome activation by suppressing basal and LPS-induced NLRP3 expression levels. A20myel-KO mice showed excessive cytokine secretion and caspase-1 processing and exhibited enhanced arthritis pathology, which was dependent on the NLRP3 inflammasome.123 The leucine-rich repeat Fli-I-interacting protein 2 (LRRFIP2) associates with NLRP3 and negatively regulates NLRP3 inflammasome activation. LRRFIP2 also interacts with Flightless-I, a pseudosubstrate of caspase-1, and promotes the inhibitory effect of Flightless-I on caspase-1 activation.124 In addition, it was recently shown that the orphan nuclear receptor SHP acts as a negative regulator of NLRP3 inflammasome activation through binding with NLRP3 and is also required for translocation of NLRP3 into mitochondria and the maintenance of mitochondrial homeostasis.107 In SHP-deficient macrophages, mitochondrial ROS generation and cytosolic translocation of mitochondrial DNA were increased significantly.107

The aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) negatively regulates NLRP3-mediated caspase-1 activation and IL-1β secretion in macrophages through binding to the xenobiotic response element in the NLRP3 promoter and inhibiting NLRP3 transcription.125 Another recent study showed that IκB kinase α (IKKα) is a negative regulator of ASC-dependent inflammasome activation through interaction with the inflammasome adaptor ASC.126 Signal 2 activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome attenuates the kinase activity of IKKα through recruitment of phosphatase PP2A, thus releasing ASC to participate in inflammasome assembly.126 Recent studies using a yeast two-hybrid screen showed that the hematopoietic-restricted G protein signaling modulator-3 (GPSM3) interacts with NLRP3 and acts as a negative regulator of IL-1β production in response to NLRP3-dependent inflammasome activators.127 In the screening of a kinase inhibitor library in another recent study, 3,4-methylenedioxy-β-nitrostyrene (MNS) was identified by the prevention of NLRP3-mediated ASC speck formation through targeting NLRP3 or NLRP3-associated complexes.128 It is also noted that caspase-1, in spite of its essential role in the assembly of NLRP3 inflammasome, is found to play a critical regulatory role in house dust mite-induced allergic lung inflammation through downregulation of IL-33.129

Recent studies have identified a key role of autophagy in activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome.130,131,132,133 Autophagy acts as a negative regulator of NLRP3 inflammasome activation through various mechanisms, including direct inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome activation by removing sources of endogenous NLRP3 inflammasome agonists, such as damaged mitochondria and mitochondrial DNA,62,69,132 suppression of IL-1β secretion by targeting pro-IL-1β for lysosomal degradation,134 and selective degradation of inflammasome components, such as NLRP3 and ASC.131,135

More detailed information on the negative regulation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, including the roles of microRNAs and autophagy, has been detailed in recent reviews.136 Together, efforts to identify new negative regulators of NLRP3 inflammasome activation may provide novel strategies to treat acute and chronic inflammatory diseases associated with aberrant activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Figure 3 presents a schematic model for various molecular pathways that negatively regulate the NLRP3 inflammasome.

Figure 3.

Schematic models for the identified negative regulators in NLRP3 inflammasome activation. A20, a well-known inhibitor for NF-κB signaling, acts as a negative regulator of NLRP3 activation and caspase-1 processing. AhR binds to the xenobiotic response element in the NLRP3 promoter and inhibits NLRP3 transcription. Several molecules (e.g., NO, MNS, GPSM3, CARD8, IKKα) play a critical role in the modulation of NLRP3 inflammasome complex assembly. NO and MNS inhibit formation of the ASC pyroptosome and speck formation by targeting the NLRP3 complex. GPSM3 and CARD8 directly bind to NLRP3 and act as negative regulators of the NLRP3 inflammasome. IKKα negatively controls the NLRP3 inflammasome through interaction with the ASC adaptor molecule. LRRFIP2 interacts with Flightless-1, a pseudosubstrate of caspase-1, and inhibits caspase-1 activation. The orphan nuclear receptor SHP interacts with NLRP3, and mediates translocation of NLRP3 into mitochondria, thus regulating NLRP3 inflammasome activation. CO plays a general inhibitory role in mitochondrial ROS generation and translocation of mitochondrial DNA into cytosol. TRIM30 also inhibits the NLRP3 inflammasome activation through modulation of ROS generation, although there is no evidence that it can bind to any partner in NLRP3 inflammasome assembly. ASC, apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a C-terminal caspase recruitment domain; A20, tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced protein 3; AhR, aryl hydrocarbon receptor; CARD8, caspase recruitment domain; CO, carbon monoxide; IKKα, IκB kinase α GPSM3, G protein signaling modulator-3; LRRFIP2, leucine-rich repeat Fli-I-interacting protein 2; MNS, 3,4-methylenedioxy-β-nitrostyrene; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; NLRP3, NACHT, LRR, and PYD domains-containing protein 3; NO, nitric oxide; SHP, small heterodimer partner; TRIM30, tripartite-motif protein 30.

Concluding Remarks

Unraveling the molecular mechanisms responsible for NLRP3 inflammasome complex activation is key for improving our understanding of host innate defenses and the pathogenesis of various inflammatory diseases associated with the NLRP3 inflammasome. Here, based on a considerable amount of data accumulated from recent studies, we showed that the NLRP3 inflammasome, the best characterized inflammasome, is activated by numerous PAMPs and DAMPs. Understanding how different PAMPs and DAMPs can induce the complex activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome remains a topic of considerable interest. In addition, identifying and characterizing specific binding partners modulating inflammasome activation in vitro and in vivo may be interesting and challenging. Obviously, our understanding of the NLRP3 inflammasome molecular mechanisms needs to be integrated with information about the exact molecular structure of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Finally, we have just begun to understand the negative regulators and their mechanisms that finely control and prevent excessive inflammasome activation. Further analysis of these negative regulators and signals should ultimately help us to modulate NLRP3 inflammasome activation therapeutically and to develop better treatments to prevent inflammatory diseases associated with the NLRP3 inflammasome.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to current and past members of our laboratory for discussions and investigations that contributed to this article. This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIP) (No. 2007-0054932) and by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIP) (2015M3C9A2054326). I apologize to colleagues whose work and publications could not be referenced owing to space constraints. The authors have no financial conflict of interests.

References

- Davis BK, Wen H, Ting JP. The inflammasome NLRs in immunity, inflammation, and associated diseases. Annu Rev Immunol 2010; 29: 707–735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Nardo D, Latz E. NLRP3 inflammasomes link inflammation and metabolic disease. Trends Immunol 2011; 32: 373–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinon F, Burns K, Tschopp J. The inflammasome: a molecular platform triggering activation of inflammatory caspases and processing of proIL-beta. Mol Cell 2002; 10: 417–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamkanfi M. Emerging inflammasome effector mechanisms. Nat Rev Immunol 2011; 11: 213–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarda G, Zenger M, Yazdi AS, Schroder K, Ferrero I, Menu P et al. Differential expression of NLRP3 among hematopoietic cells. J Immunol 2011; 186: 2529–2534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornung V, Latz E. Critical functions of priming and lysosomal damage for NLRP3 activation. Eur J Immunol 2010; 40: 620–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perregaux D, Gabel CA. Interleukin-1 beta maturation and release in response to ATP and nigericin. Evidence that potassium depletion mediated by these agents is a necessary and common feature of their activity. J Biol Chem 1994; 269: 15195–15203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pétrilli V, Papin S, Dostert C, Mayor A, Martinon F, Tschopp J. Activation of the NALP3 inflammasome is triggered by low intracellular potassium concentration. Cell Death Differ 2007; 14: 1583–1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada M, Matsuzawa A, Yoshimura A, Ichijo H. The lysosome rupture-activated TAK1-JNK pathway regulates NLRP3 inflammasome activation. J Biol Chem 2014; 289: 32926–32936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heid ME, Keyel PA, Kamga C, Shiva S, Watkins SC, Salter RD. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species induces NLRP3-dependent lysosomal damage and inflammasome activation. J Immunol 2013; 191: 5230–5238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurung P, Lukens JR, Kanneganti TD. Mitochondria: diversity in the regulation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Trends Mol Med 2015; 21: 193–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorbara MT, Girardin SE. Mitochondrial ROS fuel the inflammasome. Cell Res 2011; 21: 558–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozaki E, Campbell M, Doyle SL. Targeting the NLRP3 inflammasome in chronic inflammatory diseases: current perspectives. J Inflamm Res 2015; 8: 15–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menu P, Vince JE. The NLRP3 inflammasome in health and disease: the good, the bad and the ugly. Clin Exp Immunol 2011; 166: 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason DR, Beck PL, Muruve DA. Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptors and inflammasomes in the pathogenesis of non-microbial inflammation and diseases. J Innate Immun 2012; 4: 16–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurung P, Kanneganti TD. Novel roles for caspase-8 in IL-1β and inflammasome regulation. Am J Pathol 2015; 185: 17–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor W Jr, Harton JA, Zhu X, Linhoff MW, Ting JP. Cutting edge: CIAS1/cryopyrin/PYPAF1/NALP3/CATERPILLER 1.1 is an inducible inflammatory mediator with NF-kappa B suppressive properties. J Immunol 2003; 171: 6329–6333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman HM, Mueller JL, Broide DH, Wanderer AA, Kolodner RD. Mutation of a new gene encoding a putative pyrin-like protein causes familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome and Muckle-Wells syndrome. Nat Genet 2001; 29: 301–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornberry NA, Bull HG, Calaycay JR, Chapman KT, Howard AD, Kostura MJ et al. A novel heterodimeric cysteine protease is required for interleukin-1 beta processing in monocytes. Nature 1992; 356: 768–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y, Kuida K, Tsutsui H, Ku G, Hsiao K, Fleming MA et al. Activation of interferon-gamma inducing factor mediated by interleukin-1beta converting enzyme. Science 1997; 275: 206–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanaja SK, Rathinam VA, Fitzgerald KA. Mechanisms of inflammasome activation: recent advances and novel insights. Trends Cell Biol 2015; 25: 308–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu A, Magupalli VG, Ruan J, Yin Q, Atianand MK, Vos MR et al. Unified polymerization mechanism for the assembly of ASC-dependent inflammasomes. Cell 2014; 156: 1193–1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai X, Chen J, Xu H, Liu S, Jiang QX, Halfmann R et al. Prion-like polymerization underlies signal transduction in antiviral immune defense and inflammasome activation. Cell 2014; 156: 1207–1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner RN, Proell M, Kufer TA, Schwarzenbacher R. Evaluation of Nod-like receptor (NLR) effector domain interactions. PLoS One 2009; 4: e4931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Q, Mathison J, Fearns C, Kravchenko VV, Da Silva Correia J, Hoffman HM et al. MDP-induced interleukin-1beta processing requires Nod2 and CIAS1/NALP3. J Leukoc Biol 2007; 82: 177–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayagaki N, Wong MT, Stowe IB, Ramani SR, Gonzalez LC, Akashi-Takamura S et al. Noncanonical inflammasome activation by intracellular LPS independent of TLR4. Science 2013; 341: 1246–1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagar JA, Powell DA, Aachoui Y, Ernst RK, Miao EA. Cytoplasmic LPS activates caspase-11: implications in TLR4-independent endotoxic shock. Science 2013; 341: 1250–1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruchard M, Rebé C, Derangère V, Togbé D, Ryffel B, Boidot R et al. The receptor NLRP3 is a transcriptional regulator of TH2 differentiation. Nat Immunol 2015; 16: 859–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinarello CA. Blocking IL-1 in systemic inflammation. J Exp Med 2005; 201: 1355–1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Neill LA. The interleukin-1 receptor/toll-like receptor superfamily: 10 years of progress. Immunol Rev 2008; 226: 10–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinarello CA. Immunological and inflammatory functions of the interleukin-1 family. Annu Rev Immunol 2009; 27: 519–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinon F. Mayor A, Tschopp J. The inflammasomes: guardians of the body. Annu Rev Immunol 2009; 27: 229–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroder K, Tschopp J. The inflammasomes. Cell 2010; 140: 821–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franchi L, Muñoz-Planillo R, Núñez G. Sensing and reacting to microbes through the inflammasomes. Nat Immunol 2012; 13: 325–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koizumi Y, Toma C, Higa N, Nohara T, Nakasone N, Suzuki T. Inflammasome activation via intracellular NLRs triggered by bacterial infection. Cell Microbiol 2012; 14: 149–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JJ, Jo EK. NLRP3 inflammasome and host protection against bacterial infection. J Korean Med Sci 2013; 28: 1415–1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vladimer GI, Marty-Roix R, Ghosh S, Weng D, Lien E. Inflammasomes and host defenses against bacterial infections. Curr Opin Microbiol 2013; 16: 23–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupfer C, Kanneqanti TD. The expanding role of NLRs in antiviral immunity. Immunol Rev 2013; 255: 13–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutterwala FS, Ogura Y, Flavell RA. The inflammasome in pathogen recognition and inflammation. J Leukoc Biol 2007; 82: 259–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariathasan S, Weiss DS, Newton K, McBride J, O'Rourke K, Roose-Girma M et al. Cryopyrin activates the inflammasome in response to toxins and ATP. Nature 2006; 440: 228–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa A, Gupta R, Signorino G, Malara A, Cardile F, Biondo C et al. Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome by group B streptococci. J Immunol 2012; 188: 1953–1960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan JA, Gao X, Huang MT, O'Connor BP, Thomas CE, Willingham SB et al. Neisseria gonorrhoeae activates the proteinase cathepsin B to mediate the signaling activities of the NLRP3 and ASC-containing inflammasome. J Immunol 2009; 182: 6460–6469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichinohe T, Pang IK, Iwasaki A. Influenza virus activates inflammasomes via its intracellular M2 ion channel. Nat Immunol 2010; 11: 404–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito M, Yanagi Y, Ichinohe T. Encephalomyocarditis virus viroporin 2B activates NLRP3 inflammasome. PLoS Pathog 2012; 8: e1002857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triantafilou K, Kar S, van Kuppeveld FJ, Triantafilou M. Rhinovirus-induced calcium flux triggers NLRP3 and NLRC5 activation in bronchial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2013; 49: 923–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triantafilou K, Kar S, Vakakis E, Kotecha S, Triantafilou M. Human respiratory syncytial virus viroporin SH: a viral recognition pathway used by the host to signal inflammasome activation. Thorax 2013; 68: 66–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang IK, Iwasaki A. Control of antiviral immunity by pattern recognition and the microbiome. Immunol Rev 2012; 245: 209–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichinohe T, Lee HK, Ogura Y, Flavell R, Iwasaki A. Inflammasome recognition of influenza virus is essential for adaptive immune responses. J Exp Med 2009; 206: 79–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abderrazak A, Syrovets T, Couchie D, El Hadri K, Friguet B, Simmet T et al. NLRP3 inflammasome: from a danger signal sensor to a regulatory node of oxidative stress and inflammatory diseases. Redox Biol 2015; 4: 296–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carta S, Penco F, Lavieri R, Martini A, Dinarello CA, Gattorno M et al. Cell stress increases ATP release in NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated autoinflammatory diseases, resulting in cytokine imbalance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015; 112: 2835–2840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron L, Gombault A, Fanny M, Villeret B, Savigny F, Guillou N et al. The NLRP3 inflammasome is activated by nanoparticles through ATP, ADP and adenosine. Cell Death Dis 2015; 6: e1629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y, Franchi L, Núñez G. TLR agonists stimulate Nlrp3-dependent IL-1β production independently of the purinergic P2X7 receptor in dendritic cells and in vivo. J Immunol 2013; 190: 334–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinon F, Pétrilli V, Mayor A, Tardivel A, Tschopp J. Gout-associated uric acid crystals activate the NALP3 inflammasome. Nature 2006; 440: 237–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki K, Muto J, Taylor KR, Cogen AL, Audish D, Bertin Jet al. NLRP3/cryopyrin is necessary for interleukin-1beta (IL-1beta) release in response to hyaluronan, an endogenous trigger of inflammation in response to injury. J Biol Chem 2009; 284: 12762–12771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halle A, Hornung V, Petzold GC, Stewart CR, Monks BG, Reinheckel T et al. The NALP3 inflammasome is involved in the innate immune response to amyloid-beta. Nat Immunol 2008; 9: 857–865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dostert C, Pétrilli V, Van Bruggen R, Steele C, Mossman BT, Tschopp J. Innate immune activation through Nalp3 inflammasome sensing of asbestos and silica. Science 2008; 320: 674–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornung V, Bauernfeind F, Halle A, Samstad EO, Kono H, Rock KL et al. Silica crystals and aluminum salts activate the NALP3 inflammasome through phagosomal destabilization. Nat Immunol 2008; 9: 847–856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenbarth SC, Colegio OR, O'Connor W, Sutterwala FS, Flavell RA. Crucial role for the Nalp3 inflammasome in the immunostimulatory properties of aluminium adjuvants. Nature 2008; 453: 1122–1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besnard AG, Guillou N, Tschopp J, Erard F, Couillin I, Iwakura Y et al. NLRP3 inflammasome is required in murine asthma in the absence of aluminum adjuvant. Allergy 2011; 66: 1047–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldmeyer L, Keller M, Niklaus G, Hohl D, Werner S, Beer HD. The inflammasome mediates UVB-induced activation and secretion of interleukin-1beta by keratinocytes. Curr Biol 2007; 17: 1140–1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sollberger G, Strittmatter GE, Kistowska M, French LE, Beer HD. Caspase-4 is required for activation of inflammasomes. J Immunol 2012; 188: 1992–2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang Y, Hu C, Ding G, Zhang Y, Huang S, Jia Z et al. Albumin impairs renal tubular tight junctions via targeting the NLRP3 inflammasome. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2015; 308: 1012–1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen H, Gris D, Lei Y, Jha S, Zhang L, Huang MT et al. Fatty acid-induced NLRP3-ASC inflammasome activation interferes with insulin signaling. Nat Immunol 2011; 12: 408–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CM, McGillicuddy FC, Harford KA, Finucane OM, Mills KH, Roche HM. Dietary saturated fatty acids prime the NLRP3 inflammasome via TLR4 in dendritic cells-implications for diet-induced insulin resistance. Mol Nutr Food Res 2012; 56: 1212–1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finucane OM, Lyons CL, Murphy AM, Reynolds CM, Klinger R, Healy NP et al. Monounsaturated fatty acid-enriched high-fat diets impede adipose NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated IL-1β secretion and insulin resistance despite obesity. Diabetes 2015; 64: 2116–2128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon JS, Lee S, Park MA, Siempos II, Haslip M, Lee PJ et al. UCP2-induced fatty acid synthase promotes NLRP3 inflammasome activation during sepsis. J Clin Invest 2015; 125: 665–680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Handy DE, Loscalzo J. Redox regulation of mitochondrial function. Antioxid Redox Signal 2012; 16: 1323–1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou R, Yazdi AS, Menu P, Tschopp J. A role for mitochondria in NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Nature 2011; 469: 221–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakahira K, Haspel JA, Rathinam VA, Lee SJ, Dolinay T, Lam HC et al. Autophagy proteins regulate innate immune responses by inhibiting the release of mitochondrial DNA mediated by the NALP3 inflammasome. Nat Immunol 2011; 12: 222–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HM, Kim JJ, Kim HJ, Shong M, Ku BJ, Jo EK. Upregulated NLRP3 inflammasome activation in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 2013; 62: 194–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada K, Crother TR, Karlin J, Dagvadorj J, Chiba N, Chen S et al. Oxidized mitochondrial DNA activates the NLRP3 inflammasome during apoptosis. Immunity 2012; 36: 401–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jabaut J, Ather JL, Taracanova A, Poynter ME, Ckless K. Mitochondria-targeted drugs enhance Nlrp3 inflammasome-dependent IL-1β secretion in association with alterations in cellular redox and energy status. Free Radic Biol Med 2013; 60: 233–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer SS, He Q, Janczy JR, Elliott EI, Zhong Z, Olivier AK et al. Mitochondrial cardiolipin is required for Nlrp3 inflammasome activation. Immunity 2013; 39: 311–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong Z, Zhai Y, Liang S, Mori Y, Han R, Sutterwala FS et al. TRPM2 links oxidative stress to NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Nat Commun 2013; 4: 1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DI, Griendling KK. Nox proteins in signal transduction. Free Radic Biol Med 2009; 47: 1239–1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paletta-Silva R, Rocco-Machado N, Meyer-Fernandes JR. NADPH oxidase biology and the regulation of tyrosine kinase receptor signaling and cancer drug cytotoxicity. Int J Mol Sci 2013; 14: 3683–3704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal A, Baneriee A, Banerjee UC. Xanthine oxidoreductase: a journey from purine metabolism to cardiovascular excitation-contraction coupling. Crit Rev Biotechnol 2011; 31: 264–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz CM, Rinna A, Forman HJ, Ventura AL, Persechini PM, Ojcius DM. ATP activates a reactive oxygen species-dependent oxidative stress response and secretion of proinflammatory cytokines in macrophages. J Biol Chem 2007; 282: 2871–2879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewinson J, Moore SF, Glover C, Watts AG, MacKenzie AB. A key role for redox signaling in rapid P2X7 receptor-induced IL-1 beta processing in human monocytes. J Immunol 2008; 180: 8410–8420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meissner F, Seqer RA, Moshous D, Fischer A, Reichenbach J, Zychlinsky A. Inflammasome activation in NADPH oxidase defective mononuclear phagocytes from patients with chronic granulomatous disease. Blood 2010; 116: 1570–1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Veerdonk FL, Smeekens SP, Joosten LA, Kullberg BJ, Dinarello CA, van der Meer JW et al. Reactive oxygen species-independent activation of the IL-1beta inflammasome in cells from patients with chronic granulomatous disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010; 107: 3030–3033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Bruggen R, Köker MY, Jansen M, van Houdt M, Roos D, Kuijpers TW et al. Human NLRP3 inflammasome activation is Nox1-4 independent. Blood 2010; 115: 5398–5400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meissner F, Molawi K, Zychlinsky A. Superoxide dismutase 1 regulates caspase-1 and endotoxic shock. Nat Immunol 2008; 9: 866–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauernfeind F, Bartok E, Rieger A, Franchi L, Núñez G, Hornung V. Cutting edge: reactive oxygen species inhibitors block priming, but not activation, of the NLRP3 inflammasome. J Immunol 2011; 187: 613–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ives A, Nomura J, Martinon F, Roger T, LeRoy D, Miner JN et al. Xanthine oxidoreductase regulates macrophage IL1β secretion upon NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Nat Commun 2015; 6: 6555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Planillo R, Franchi L, Miller LS, Núñez G. A critical role for hemolysins and bacterial lipoproteins in Staphylococcus aureus-induced activation of the Nlrp3 inflammasome. J Immunol 2009; 183: 3942–3948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Planillo R, Kuffa P, Martínez-Colón G, Smith BL, Rajendiran TM, Núñez G. K+ efflux is the common trigger of NLRP3 inflammasome activation by bacterial toxins and particulate matter. Immunity 2013; 38: 1142–1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross O, Poeck H, Bscheider M, Dostert C, Hannesschläger N, Endres S et al. Syk kinase signalling couples to the Nlrp3 inflammasome for anti-fungal host defence. Nature 2009; 459: 433–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrella D, Pandev N, Gabrielli E, Pericolini E, Perito S, Kasper L et al. Secreted aspartic proteases of Candida albicans activate the NLRP3 inflammasome. Eur J Immunol 2013; 43: 679–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saïd-Sadier N, Padilla E, Langsley G, Ojcius DM. Aspergillus fumigatus stimulates the NLRP3 inflammasome through a pathway requiring ROS production and the Syk tyrosine kinase. PLoS One 2010; 5: e10008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin C, Frayssinet P, Pelker R, Cwirka D, Hu B, Vignery A et al. NLRP3 inflammasome plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of hydroxyapatite-associated arthropathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011; 108: 14867–14872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauter KA, Wood LJ, Wong J, Iordanov M, Magun BE. Doxorubicin and daunorubicin induce processing and release of interleukin-1β through activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Cancer Biol Ther 2011; 11: 1008–1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp FA, Ruane D, Claass B, Creagh E, Harris J, Malyala P et al. Uptake of particulate vaccine adjuvants by dendritic cells activates the NALP3 inflammasome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009; 106: 870–875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlan AU, Griffin TM, McGuire KA, Wiethoff CM. Adenovirus membrane penetration activates the NLRP3 inflammasome. J Virol 2011; 85: 146–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta R, Ghosh S, Monks B, DeOliveira RB, Tzeng TC, Kalantari P et al. RNA and beta-hemolysin of group B Streptococcus induce interleukin-1β (IL-1β) by activating NLRP3 inflammasomes in mouse macrophages. J Biol Chem 2014; 289: 13701–13705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Wen Y, Tang TT, Lv LL, Tang RN, Liu H et al. Megalin/cubulin-lysosome-mediated albumin reabsorption is involved in the tubular cell activation of NLRP3 inflammasome and tubulointerstitial inflammation. J Biol Chem 2015; 290: 18018–18028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujisawa A, Kambe N, Saito M, Nishikomori R, Tanizaki H, Kanazawa N et al. Disease-associated mutations in CIAS1 induce cathepsin B-dependent rapid cell death of human THP-1 monocytic cells. Blood 2007; 109: 2903–2911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergsbaken T, Fink SL, den Hartigh AB, Loomis WP, Cookson BT. Coordinated host responses during pyroptosis: caspase-1-dependent lysosome exocytosis and inflammatory cytokine maturation. J Immunol 2011; 187: 2748–2754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima H Jr, Jacobson LS, Goldberg MF, Chandran K, Diaz-Griffero F, Lisanti MPet al. Role of lysosome rupture in controlling Nlrp3 signaling and necrotic cell death. Cell Cycle 2013; 12: 1868–1878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilling JD, Machkovech HM, He L, Diwan A, Schaffer JE. TLR4 activation under lipotoxic conditions leads to synergistic macrophage cell death through a TRIF-dependent pathway. J Immunol 2013; 190: 1285–1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber K, Schilling JD. Lysosomes integrate metabolic-inflammatory cross-talk in primary macrophage inflammasome activation. J Biol Chem 2014; 289: 9158–9171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duewell P, Kono H, Rayner KJ, Sirois CM, Vladimer G, Bauernfeind FG et al. NLRP3 inflammasomes are required for atherogenesis and activated by cholesterol crystals. Nature 2010; 464: 1357–1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summersgill H, England H, Lopez-Castejon G, Lawrence CB, Luheshi NM, Pahle J et al. Zinc depletion regulates the processing and secretion of IL-1β. Cell Death Dis 2014; 5: e1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riteau N, Baron L, Villeret B, Guillou N, Savigny F, Ryffel B et al. ATP release and purinergic signaling: a common pathway for particle-mediated inflammasome activation. Cell Death Dis 2012; 3: e403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misawa T, Takahama M, Kozaki T, Lee H, Zou J, Saitoh T et al. Microtubule-driven spatial arrangement of mitochondria promotes activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Nat Immunol 2013; 14: 454–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian N, Natarajan K, Clatworthy MR, Wang Z, Germain RN. The adaptor MAVS promotes NLRP3 mitochondrial localization and inflammasome activation. Cell 2013; 153: 348–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang CS, Kim JJ, Kim TS, Lee PY, Kim SY, Lee HM et al. Small heterodimer partner interacts with NLRP3 and negatively regulates activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Nat Commun 2015; 6: 6115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raturi A, Simmen T. Where the endoplasmic reticulum and the mitochondrion tie the knot: the mitochondria-associated membrane (MAM). Biochim Biophys Acta 2013; 1833: 213–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Man SM, Hopkins LJ, Nugent E, Cox S, Gluck IM, Tourlomousis P et al. Inflammasome activation causes dual recruitment of NLRC4 and NLRP3 to the same macromolecular complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014; 111: 7403–7408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou R, Tardivel A, Thorens B, Choi I, Tschopp J. Thioredoxin-interacting protein links oxidative stress to inflammasome activation. Nat Immunol 2010; 2: 136–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenoy AR, Wellington DA, Kumar P, Kassa H, Booth CJ, Cresswell P et al. GBP5 promotes NLRP3 inflammasome assembly and immunity in mammals. Science 2012; 336: 481–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers MA, Bowman JW, Fujita H, Orazio N, Shi M, Liang Q et al. The linear ubiquitin assembly complex (LUBAC) is essential for NLRP3 inflammasome activation. J Exp Med 2014; 211: 1333–1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitoma H, Hanabuchi S, Kim T, Bao M, Zhang Z, Sugimoto N et al. The DHX33 RNA helicase senses cytosolic RNA and activates the NLRP3 inflammasome. Immunity 2013; 39: 123–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu B, Nakamura T, Inouye K, Li J, Tang Y, Lundback P et al. Novel role of PKR in inflammasome activation and HMGB1 release. Nature 2012; 488: 670–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee GS, Subramanian N, Kim AI, Aksentijevich I, Goldbach-Mansky R, Sacks DB et al. The calcium-sensing receptor regulates the NLRP3 inflammasome through Ca2+ and cAMP. Nature 2012; 492: 123–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichinohe T, Yamazaki T, Koshiba T, Yanagi Y. Mitochondrial protein mitofusin 2 is required for NLRP3 inflammasome activation after RNA virus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013; 110: 17963–17968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Jiang W, Yan Y, Gong T, Han J, Tian Z et al. RNA viruses promote activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome through a RIP1-RIP3-DRP1 signaling pathway. Nat Immunol 2014; 15: 1126–1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutterwala FS, Haasken S, Cassel SL. Mechanism of NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2014; 1319: 82–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Mao K, Zeng Y, Chen S, Tao Z, Yang C et al. Tripartite-motif protein 30 negatively regulates NLRP3 inflammasome activation by modulating reactive oxygen species production. J Immunol 2010; 185: 7699–7705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao K, Chen S, Chen M, Ma Y, Wang Y, Huang B et al. Nitric oxide suppresses NLRP3 inflammasome activation and protects against LPS-induced septic shock. Cell Res 2013; 23: 201–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung SS, Moon JS, Xu JF, Ifedigbo E, Ryter SW, Choi AM et al. Carbon monoxide negatively regulates NLRP3 inflammasome activation in macrophages. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2015; 308: 1058–1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito S, Hara Y, Kubota T. CARD8 is a negative regulator for NLRP3 inflammasome, but mutant NLRP3 in cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes escapes the restriction. Arthritis Res Ther 2014; 16: R52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vande Walle L, Van Opdenbosch N, Jacques P, Fossoul A, Verheugen E, Vogel P et al. Negative regulation of the NLRP3 inflammasome by A20 protects against arthritis. Nature 2014; 512: 69–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin J, Yu Q, Han C, Hu X, Xu S, Wang Q et al. LRRFIP2 negatively regulates NLRP3 inflammasome activation in macrophages by promoting Flightless-I-mediated caspase-1 inhibition. Nat Commun 2013; 4: 2075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huai W, Zhao R, Song H, Zhao J, Zhang L, Zhang L et al. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor negatively regulates NLRP3 inflammasome activity by inhibiting NLRP3 transcription. Nat Commun 2014; 5: 4738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin BN, Wang C, Willette-Brown J, Herjan T, Gulen MF, Zhou H et al. IKKα negatively regulates ASC-dependent inflammasome activation. Nat Commun 2014; 5: 4977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giguère PM, Gall BJ, Ezekwe EA Jr, Laroche G, Buckley BK, Kebaier C et al. G protein signaling modulator-3 inhibits the inflammasome activity of NLRP3. J Biol Chem 2014; 289: 33245–33257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y, Varadarajan S, Munoz-Planillo R, Burberry A, Nakamura Y, Nunez G. 3,4-methylenedioxy-beta-nitrostyrene inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome activation by blocking assembly of the inflammasome. J Biol Chem 2014; 289: 1142–1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madouri F, Guillou N, Fauconnier L, Marchiol T, Rouxel N, Chenuet P et al. Caspase-1 activation by NLRP3 inflammasome dampens IL-33-dependent house dust mite-induced allergic lung inflammation. J Mol Cell Biol 2015; 7: 351–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitoh T, Fujita N, Jang MH, Uematsu S, Yang BG, Satoh T et al. Loss of the autophagy protein Atg16L1 enhances endotoxin-induced IL-1beta production. Nature 2008; 456: 264–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang SY, Yang CH, Chou CC, Chiang YP, Chuang TH, Hsu LC. TLR-induced PAI-2 expression suppresses IL-1β processing via increasing autophagy and NLRP3 degradation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013; 110: 16079–16084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Burgh R, Nijhuis L, Pervolaraki K, Compeer EB, Jongeneel LH, van Gijn M et al. Defects in mitochondrial clearance predispose human monocytes to interleukin-1β hypersecretion. J Biol Chem 2014; 289: 5000–5012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deretic V, Kimura T, Timmins G, Moseley P, Chauhan S, Mandell M. Immunologic manifestations of autophagy. J Clin Invest 2015; 125: 75–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris J, Hartman M, Roche C, Zeng SG, O'Shea A, Sharp FA et al. Autophagy controls IL-1beta secretion by targeting pro-IL-1beta for degradation. J Biol Chem 2011; 286: 9587–9597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi CS, Shenderov K, Huang NN, Kabat J, Abu-Asab M, Fitzgerald KA et al. Activation of autophagy by inflammatory signals limits IL-1β production by targeting ubiquitinated inflammasomes for destruction. Nat Immunol 2012; 13: 255–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedraza-Alva G, Perez-Martinez L, Valdez-Hernandez L, Meza-Sosa KF, Ando-Kuri M. Negative regulation of the inflammasome: keeping inflammation under control. Immunol Rev 2015; 265: 231–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]