Background: Diminished activity of the enzyme AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is associated with impaired insulin signaling.

Results: Protein Kinase (PK)C/D1 activation inhibits AMPKα2 via Ser491 phosphorylation; PKD1 inhibition prevents this in skeletal muscle cells.

Conclusion: PKD1 is a novel upstream AMPK-kinase that phosphorylates AMPK on Ser491 and regulates insulin signaling.

Significance: PKD1 inhibition may be a novel strategy for improving insulin sensitivity.

Keywords: Akt PKB, AMP-activated kinase (AMPK), insulin resistance, protein kinase C (PKC), protein kinase D (PKD), skeletal muscle, Serine485/491

Abstract

AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is an energy-sensing enzyme whose activity is inhibited in settings of insulin resistance. Exposure to a high glucose concentration has recently been shown to increase phosphorylation of AMPK at Ser485/491 of its α1/α2 subunit; however, the mechanism by which it does so is not known. Diacylglycerol (DAG), which is also increased in muscle exposed to high glucose, activates a number of signaling molecules including protein kinase (PK)C and PKD1. We sought to determine whether PKC or PKD1 is involved in inhibition of AMPK by causing Ser485/491 phosphorylation in skeletal muscle cells. C2C12 myotubes were treated with the PKC/D1 activator phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), which acts as a DAG mimetic. This caused dose- and time-dependent increases in AMPK Ser485/491 phosphorylation, which was associated with a ∼60% decrease in AMPKα2 activity. Expression of a phosphodefective AMPKα2 mutant (S491A) prevented the PMA-induced reduction in AMPK activity. Serine phosphorylation and inhibition of AMPK activity were partially prevented by the broad PKC inhibitor Gö6983 and fully prevented by the specific PKD1 inhibitor CRT0066101. Genetic knockdown of PKD1 also prevented Ser485/491 phosphorylation of AMPK. Inhibition of previously identified kinases that phosphorylate AMPK at this site (Akt, S6K, and ERK) did not prevent these events. PMA treatment also caused impairments in insulin-signaling through Akt, which were prevented by PKD1 inhibition. Finally, recombinant PKD1 phosphorylated AMPKα2 at Ser491 in cell-free conditions. These results identify PKD1 as a novel upstream kinase of AMPKα2 Ser491 that plays a negative role in insulin signaling in muscle cells.

Introduction

Skeletal muscle is responsible for ∼80% of insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in healthy humans (1). Thus, tight regulation of insulin signaling and glucose uptake in muscle cells is essential to maintaining normal blood glucose levels and overall metabolic health. This process can become dysregulated in pathological settings of insulin resistance, such as type 2 diabetes (T2D),2 which currently affects over 300 million people worldwide (2). At a cellular level, prolonged exposure to excess nutrients, such as glucose, leucine, and free fatty acids (FFA), can impair the signaling processes that normally regulate glucose uptake. Though these pathways have been studied in detail, a better understanding of the pathological changes that lead to dysfunctional insulin signaling is essential for improving therapeutic strategies.

AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is an energy sensing enzyme that is regarded as a master regulator of cellular metabolism (3). This serine/threonine kinase is activated when cellular energy levels are low (high AMP:ATP ratio) and its activation signals for the cell to increase catabolic (energy generating) processes, such as glucose uptake and fatty acid oxidation, and to inhibit anabolic (energy consuming) processes, such as protein and triglyceride synthesis. AMPK is activated by both its phosphorylation on Thr172 and allosteric modification of its catalytic α-subunit. Activated AMPK, in turn, mediates some of the beneficial metabolic effects of exercise and pharmacological activators, such as biguanides, and thiazolidinediones, which improve insulin sensitivity. Recent studies suggest that an inhibitory phosphorylation site at Ser485/491 of AMPK α1/α2 subunits plays an important role in diminishing its enzyme activity (4–7). We recently found that incubation of rat extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscle with elevated glucose levels (25 versus 5.5 mm) for 1 or 2 h both increased the phosphorylation of AMPK at Ser485/491 and diminished its phosphorylation at Thr172, both of which decreased its enzyme activity, as measured by the SAMS peptide assay (8). Similarly, it has been reported that when MIN6 pancreatic beta cells are switched from low glucose (3 mm) culture medium to high glucose (25 mm) for either 1 h or overnight, phosphorylation of AMPKα1 at Ser485 is increased, and phosphorylation at Thr172 is diminished (9).

Several upstream kinases have been identified that phosphorylate AMPK at Ser485/491 and inhibit its activity in various tissues. For example, in heart, skeletal muscle, and liver, insulin and IGF-1 stimulate AMPK phosphorylation at this site by activating Akt (4, 7, 10, 11). Also, in the hypothalamus, Dagon et al. (4, 5) showed that p70S6K phosphorylates AMPKα2 Ser491 to inhibit AMPK activity and decrease food intake. Others have shown that in murine macrophage-like RAW 264.7 cells, IKKβ phosphorylates AMPK at Ser485 in response to LPS treatment (12), while ERK1/2 can inhibit AMPK by this mechanism in mature dendritic cells in response to CCR7 signaling (13). Finally, protein kinase A (PKA) has been reported to phosphorylate this site in INS-1 cells in response to forskolin or GIP stimulation (14) and in human diploid fibroblasts in response to lysophosphatidic acid (15). Inhibition of AMPK through this mechanism by multiple kinases suggests a biological need to maintain tight control over AMPK enzyme activity. Whether still other kinases also phosphorylate AMPK at Ser485/491 to modulate its activity and biological functions remain to be determined.

Protein kinase C (PKC) is a family of serine/threonine kinases that can be activated by diacylglycerol (DAG), a phospholipid, and Ca2+ (depending on the isoform). Several of the 10 known PKC isoforms have long been implicated in the development of insulin resistance, but beyond inhibitory serine phosphorylation of IRS-1 (16), the mechanisms by which they do so have not been fully clarified. Protein kinase D1 (PKD1) (the mouse ortholog of human PKCμ) is a related kinase that can be activated either directly by DAG or due to phosphorylation by novel PKC isoforms (17). When activated, PKD1 undergoes transphosphorylation by novel PKCs at Ser744/748 of its activation loop and autophosphorylation at Ser916 at its C terminus. This more recently discovered enzyme was initially classified as an atypical PKC isoform, but was later determined to be more similar structurally to the calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaMK) group of serine/threonine kinases with unique substrate specificity (17, 18). Pathological overactivation of PKD1 has been linked to the invasiveness of certain cancers (19) and to cardiac hypertrophy (20, 21), the latter of which is often present in patients with T2D. Whether alterations in PKD1 expression or activity affect AMPK activation is not yet known. What is clear is that the DAG mimetic phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), which activates PKC and PKD1, as well as many other signaling molecules, decreases AMPK activity in cardiac myocytes (22), although the mechanism by which it does so is unknown.

In the present study, we sought to determine whether PKC or PKD1 is involved in the inhibition of AMPK by phosphorylation at Ser485/491 in skeletal muscle cells. We used the phorbol ester PMA to determine the effects of broad PKC/PKD1 activation on AMPK phosphorylation and activity. By the use of nonspecific and specific PKC and PKD1 inhibition, we show for the first time that PKD1 phosphorylates AMPK at Ser485/491, thus diminishing AMPK activity.

Experimental Procedures

Materials

C2C12 cells were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA). DMEM, Penicillin-Streptomycin (P/S), fetal bovine serum (FBS), and horse serum (HS) were from Invitrogen (Grand Island, NY). d-(+)-Glucose solution, 45%, and insulin were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Primary antibodies for acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC), AMPK, phospho-AMPKα (Thr172), phospho-AMPKα1/α2 (Ser485/491), phospho-PKD1 (Ser916), phospho-PKD1 (Ser744/748), PKD1, phospho-PKC (pan) (βII Ser660), phospho-PKCδ/θ (Ser643/676), phospho-(Ser) PKC Substrate, phosphor-(Ser/Thr) PKD substrate, phospho-mTOR (Ser2448), mTOR, phospho-p70S6K (Thr389), phosphor-ERK (Thr202/Tyr204), phospho-Akt (Ser473), and Akt antibodies, as well as secondary horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-linked antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). Phospho-ACC (Ser79) antibody was from Upstate/Millipore (Temecula, CA). Anti-β-actin and anti-FLAG were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. PRKD1 siRNA and corresponding negative control scrambled siRNA were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA). AMPKα1 and α2 antibodies used for immunoprecipitation were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. SAMS peptide was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA) and [γ-32P]ATP was from Perkin-Elmer (Boston, MA).

Cell Culture

C2C12 myoblasts were cultured in normal glucose (5.5 mm) DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% glutamine, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (P/S). Medium was replaced every 24–48 h, and cells were passaged upon reaching 80–90% confluence. At 80–90% confluence they were differentiated into myotubes in DMEM supplemented with 2% horse serum and 1% P/S. Glucose and FBS-free DMEM, supplemented with 1% P/S and glucose at a final concentration of 5.5 mm, was used for all experimental incubations.

Transfection Studies

Cells were transfected with Lipofectamine 3000 (for FLAG-WT AMPKα2/FLAG-S491A AMPKα2studies) or Lipofectamine RNAimax (for siRNA studies) according to the manufacturer's instructions. C2C12 cells were transfected on day 3 of differentiation, and experiments were performed on day 5 of differentiation.

Cell Lysate Preparation

Cells were washed once on ice with Dulbecco's PBS, lysed in buffer containing 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm Na2EDTA, 1% Triton, 2.5 mm sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mm β-glycerophosphate, 1 mm Na3VO4, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, 1× phosphatase inhibitor mixture 3 (Sigma), and 1x protease inhibitor mixture containing 0.5 mm EDTA (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and removed from wells using a cell scraper with a polyethylene copolymer blade (Fisher Scientific). Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 13,200 × g for 10 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was removed and stored at −80 °C until analysis. Protein concentration was assessed by the bicinchoninic acid method (BCA; Pierce Biotechnology, Inc., Rockford, IL).

SDS-PAGE Western Blot Analysis

Protein expression and phosphorylation were determined in 15–30 μg of protein lysate using SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting. Following transfer onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, membranes were blocked in Tris-buffered saline (pH 7.5) containing 0.05% Tween-20 (v/v; TBST) and 5% nonfat dry milk (w/v) for 1 h at room temperature, followed by incubation in primary antibodies (1:1,000) at 4 °C overnight. After washing, membranes were incubated in a secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase at a 1:5,000 dilution for 1 h at room temperature. Bands were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence solution (ECL; Pierce Biotechnology, Inc., Rockford, IL), and densitometry was performed with Scion Image software.

AMPK Activity Assay

AMPK activity was assessed as previously described (23, 24). Briefly, AMPK α1 or α2 was immunoprecipitated from 500 μg of protein from cell lysates by incubation at 4 °C overnight on a roller mixer using AMPK α1 or α2-specific antibodies (1:80) and protein A/G-agarose beads (1:10; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc). Following several washes, activity was measured in the presence of 200 μm AMP and 80 μm [γ-32P]ATP (2 μCi) using 200 μm SAMS peptide (Abcam) as a substrate. Label incorporation into the SAMS peptide was quantified using a LabLogic (Brandon, FL) scintillation counter.

Cell-free in Vitro Phosphorylation Assay

Recombinant proteins were purchased from EMD Millipore (Billerica, MA) (AMPK) and Enzo Life Sciences (Farmington, NY) (PKD1 and Akt). Recombinant α2AMPK/β1/γ1 complex was incubated with recombinant Akt or PKD1 in 50 mm Na-HEPES, 5 mm MgCl2, 500 μm ATP, 1 mm DTT for 30 min at 30 °C.

Statistical Analysis

Results are reported as means ± S.E. of the mean (S.E.). Statistical significance was determined by two-tailed unpaired Student's t tests or ANOVA with Tukey's post-hoc test. A level of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The PKC Activator PMA Dose- and Time-dependently Stimulates AMPK Ser485/491 Phosphorylation in C2C12 Myotubes

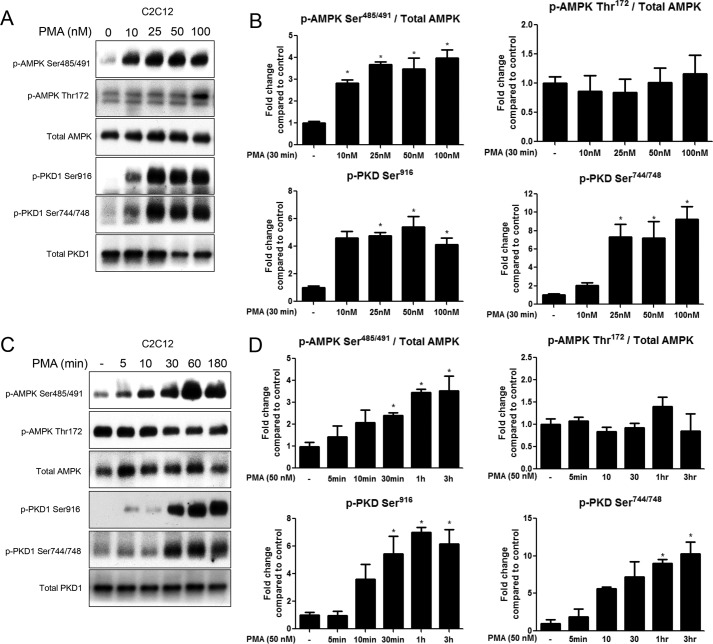

Treatment with the PKC activator phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) has previously been shown to decrease AMPK activity in cardiac myocytes, as measured by the SAMS peptide assay (22). We sought to determine whether PMA had the same effect in C2C12 myotubes, and if so, whether it is mediated by an inhibitory phosphorylation on AMPK α1/α2 subunit at Ser485/491. All doses of PMA (10–100 nm) significantly increased serine phosphorylation of AMPK (Fig. 1, A and B), as did PMA treatment for 30 min to 3 h (50 nm) (Fig. 1, C and D). Increases in overall PKC activity, as measured by serine phosphorylation of PKC substrates (data not shown), mirrored the increases in phosphorylation of AMPK Ser485/491. Phosphorylation of PKD at Ser916 and Ser744/748 of its activation loop were also significantly increased by incubation with PMA at doses of 25 nm or higher for 30 min to 3 h (Fig. 1, A–D). Since phosphorylation of these two sites changed similarly in response to all treatments, only the data for Ser916 phosphorylation is shown for subsequent experiments. Notably, no significant changes in phosphorylation of AMPK Thr172 (Fig. 1, A and C) or its downstream substrate ACC Ser79 (data not shown) were observed. Phosphorylation of conventional PKC isoforms, as measured by p-PKC (pan) (βII Ser660), was increased in a dose-response manner; however, activation of the atypical PKCι was not increased by PMA treatment (data not shown).

FIGURE 1.

PMA treatment time- and dose-dependently stimulates phosphorylation of AMPK at Ser485/491 in C2C12 myotubes. Myotubes were treated with 10–100 nm PMA for 30 min (A, B) or 50 nm PMA for 5–180min (C, D). Cells were lysed and protein expression and phosphorylation were analyzed by Western blot. Representative Western blots (A, C) and their densitometric analyses (B, D) are shown. Results are means ± S.E. (n = 3–6 per treatment). All experiments were performed in triplicate. *, p < 0.05 compared with control.

The Non-selective PKC Inhibitor Gö6983 Prevents PMA-induced Phosphorylation of AMPK Ser485/491in the Myotubes

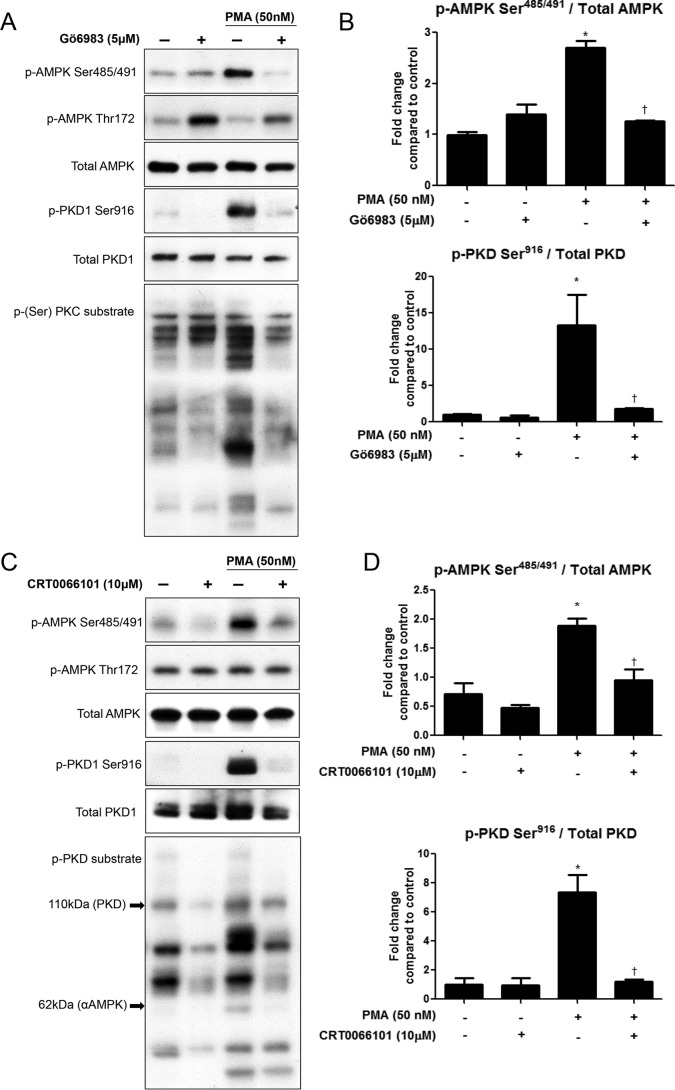

To determine whether the increase in phosphorylation of AMPK at Ser485/491 was attributable to PKC activation, we used the non-selective PKC inhibitor Gö6983. Treatment of C2C12 myotubes with Gö6983 (5 μm) for 1 h prior to PMA treatment (50 nm, 30 min) significantly attenuated phosphorylation of AMPK at Ser485/491 (Fig. 2, A and B). Phosphorylation of AMPK Thr172 (Fig. 2A) was not affected by PMA treatment, but it was increased by the inhibitor. PKC activity, assessed by serine phosphorylation of PKC substrates, was decreased by the inhibitor (Fig. 2A), as was phosphorylation of conventional PKC isoforms, when evaluated by phospho-PKC β pan, and PKD at Ser916 (Fig. 2, A and B), but not PKC δ/θ (data not shown).

FIGURE 2.

PKD inhibition prevents PMA-induced phosphorylation of AMPK Ser485/491 in C2C12 myotubes. Myotubes were treated with the nonspecific PKC inhibitor Gö6983 (5 μm) (A, B) or the specific PKD inhibitor CRT0066101 (10 μm) (C, D) for 1 h prior to PMA treatment (50 nm, 30 min). Cells were lysed and protein expression and phosphorylation were analyzed by Western blot. Representative Western blots (A, C) and their densitometric analyses (B, D) are shown. Results are means ± S.E. (n = 3–6 per treatment). All experiments were performed in triplicate. *, p < 0.05 compared with control; †, p < 0.05 compared with PMA treatment.

The Selective PKD1 Inhibitor CRT0066101 Prevents PMA-induced Phosphorylation of AMPK Ser485/491

Since phosphorylation of the activation loop of PKD at Ser744/748 and at Ser916 (Fig. 2, A and B) corresponded with changes in phosphorylation of AMPK at Ser485/491, we investigated whether specific inhibition of PKD could attenuate PMA-induced serine phosphorylation of AMPK. Pre-treatment for 1h with the specific PKD inhibitor CRT0066101 (10 μm) prevented phosphorylation of AMPK Ser485/491 in C2C12 myotubes (Fig. 2, C and D). Phosphorylation of AMPK at Thr172 was unchanged by treatment with this inhibitor (Fig. 2C). As expected, PMA effects on PKD Ser916 phosphorylation were ablated by CRT0066101 treatment, and probing with a phospho-(Ser/Thr) PKD substrate antibody revealed an overall increase in number of bands and band intensity with PMA treatment, which was prevented by pretreatment with CRT0066101 (Fig. 2C). Bands detected by this antibody at 110 kDa and 62 kDa may represent PKD (which is autophosphorylated at Ser916) and AMPK, respectively.

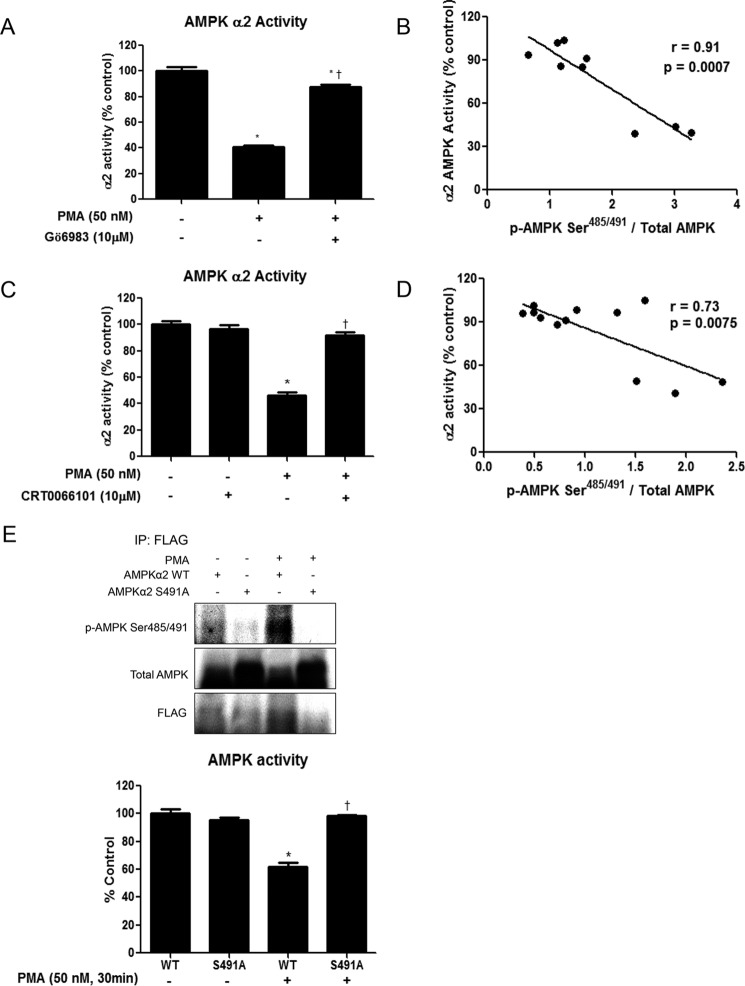

PMA Treatment Inhibits AMPK Activity, which Is Attenuated by Pretreatment with Gö6983 or CRT0066101

Recent studies have shown that phosphorylation of AMPK Ser485/491 can inhibit its activity, even in the absence of diminished Thr172 phosphorylation, which is often used as a surrogate readout for enzyme activity (4, 5). We sought to determine whether the changes in phosphorylation of AMPK Ser485/491 caused by PMA and the PKC/D inhibitors Gö6983 and CRT0066101 corresponded to changes in AMPK activity. Using the SAMS peptide assay described in the methods section, we found that PMA treatment significantly decreased AMPKα2 activity in C2C12 myotubes (Fig. 3, A and C). Furthermore, pretreatment with the non-selective PKC inhibitor Gö6983 significantly attenuated the reduction in enzyme activity (Fig. 3A), while the specific PKD inhibitor CRT0066101 completely prevented the PMA-induced decrease in AMPK activity (Fig. 3C). Despite the lack of changes in phosphorylation of AMPK Thr172 or ACC Ser79, we found a significant inverse correlation between AMPKα2 activity and phosphorylation at Ser485/491 (Fig. 3, B and D).

FIGURE 3.

PMA treatment diminishes AMPK activity in C2C12 myotubes, while PKC and PKD inhibition or expression of S491A AMPKα2 prevent this decrease. C2C12 myotubes were treated with the nonspecific PKC inhibitor Gö6983 (5 μm) (A) or the specific PKD inhibitor CRT0066101 (10 μm) (C) for 1 h prior to PMA treatment (50 nm, 30 min). AMPKα2 activity was measured by the SAMS peptide assay. B and D show the correlation between AMPKα2 activity and Ser485/491 phosphorylation. E, C2C12 cells were transfected with FLAG-tagged WT AMPKα2 or S491A AMPKα2. 48 h later, cells were treated with PMA (50 nm, 30 min) and then lysed and immunoprecipitated using an anti-FLAG antibody. Protein phosphorylation and expression were analyzed by Western blot. AMPK activity was measured using the SAMS peptide assay. Results are means ± S.E. (n = 3–6 per treatment). *, p < 0.05 compared with control; †, p < 0.05 compared with PMA treatment.

Phosphorylation of AMPK α2 on Ser491 Is Necessary for PMA-induced Inhibition of AMPK Activity

To determine if serine phosphorylation is required for the PMA-induced reduction in AMPK activity, C2C12 cells were transfected with WT AMPKα2 or phosphodefective S491A AMPKα2. As expected, phosphorylation of AMPK at Ser491 under both basal and PMA-treated conditions was prevented in the S491A AMPKα2-expressing cells (Fig. 3E). While PMA significantly decreased AMPKα2 activity, as measured by the SAMS peptide assay, in cells transfected with WT AMPKα2, no effect of PMA treatment was observed in the S491A AMPKα2-expressing cells. These data suggest that Ser491 phosphorylation of AMPKα2 is required for the PMA-induced inhibition of AMPK activity.

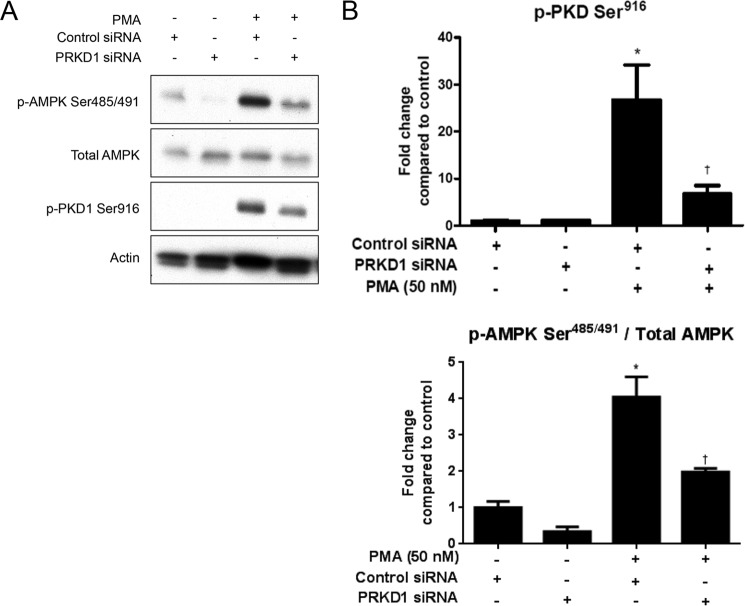

Knockdown of PKD1 Prevents PMA-induced Phosphorylation of AMPK Ser485/491

To confirm the results obtained using pharmacological inhibitors which suggested that PKD1 is involved in PMA-induced AMPK Ser485/491 phosphorylation (Fig. 2), we used siRNA to reduce PKD1 mRNA, and hence protein, levels. As expected, transfection of C2C12 cells with PKD1 (gene name PRKD1) caused a reduction in phospho-PKD1 (Fig. 4, A and B). Consistent with data shown in Fig. 2, PKD1 knockdown prevented the PMA-induced increase in AMPK Ser485/491 phosphorylation. These data offer further evidence that PKD1 is responsible for PMA-induced inhibition of AMPK by Ser485/491 phosphorylation.

FIGURE 4.

PKD1 knockdown prevents PMA-induced phosphorylation of AMPK Ser485/491 in C2C12 myotubes. C2C12 myotubes were transfected with scrambled or PKD1 siRNA. 48 h later, they were treated with PMA (50 nm, 30min). Cells were lysed, and protein expression and phosphorylation were analyzed by Western blot. Representative Western blots (A) and their densitometric analyses (B) are shown. Results are means ± S.E. (n = 3–6 per treatment). All experiments were performed in triplicate. *, p < 0.05 compared with control; †, p < 0.05 compared with PMA treatment.

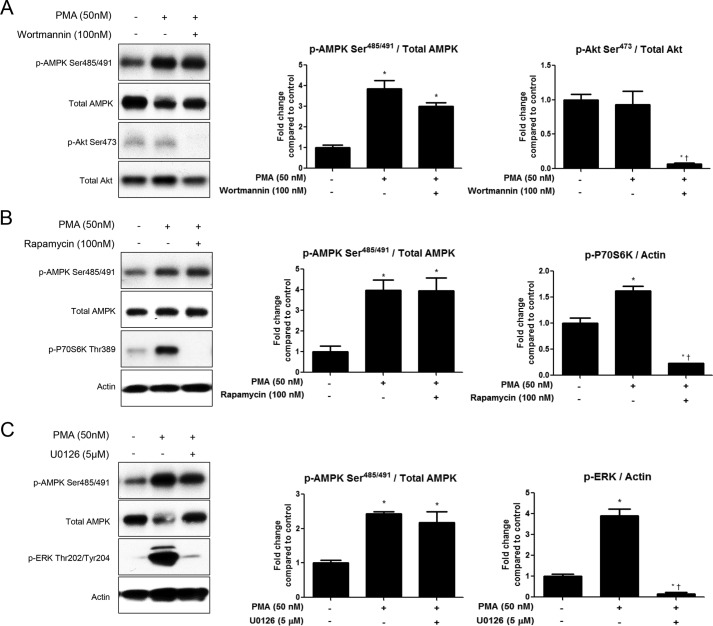

Inhibition of Akt, P70S6K, or ERK Does Not Prevent PMA-induced Phosphorylation of AMPK Ser485/491

As previously mentioned, the kinases Akt, P70S6K, and ERK1/2 have been shown to phosphorylate AMPK at Ser485/491 in response to various stimuli in other cell types. To rule out involvement of these kinases in PMA-induced phosphorylation of AMPK Ser485/491, we used inhibitors of each of these kinases. Pretreatment of C2C12 myotubes with the PI3K/Akt inhibitor wortmannin (100 nm) did not affect PMA-stimulated serine phosphorylation of AMPK (Fig. 5A). As expected, PMA treatment did not increase Akt phosphorylation, but p-Akt Ser473 phosphorylation was diminished by wortmannin treatment. Next, we used the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin to test whether P70S6K was involved. Although P70S6K Thr389 phoshphorylation was increased by PMA treatment, rapamycin (100 nm) treatment did not did not affect PMA-induced phosphorylation of AMPK Ser485/491 (Fig. 5B). Similarly, pretreatment with the ERK inhibitor U0126 (5 μm) had no effect on AMPK serine phosphorylation (Fig. 5C), despite inhibiting ERK phosphorylation, which can occur downstream of PKD.

FIGURE 5.

Inhibition of Akt, S6K, or ERK does not prevent PMA-induced phosphorylation of AMPK Ser485/491. Myotubes were treated with the PI3K/Akt inhibitor wortmannin (100 nm) (A), the mTOR/P70S6K inhibitor rapamycin (100 nm) (B), or the ERK inhibitor U0126 (5 μm) (C) for 2 h prior to PMA treatment (50 nm, 30 min). Cells were lysed, and protein expression and phosphorylation were analyzed by Western blot. Representative Western blots and their densitometric analyses are shown. Results are means ± S.E. (n = 3–6 per treatment). All experiments were performed in triplicate. *, p < 0.05 compared with control; †, p < 0.05 compared with PMA treatment.

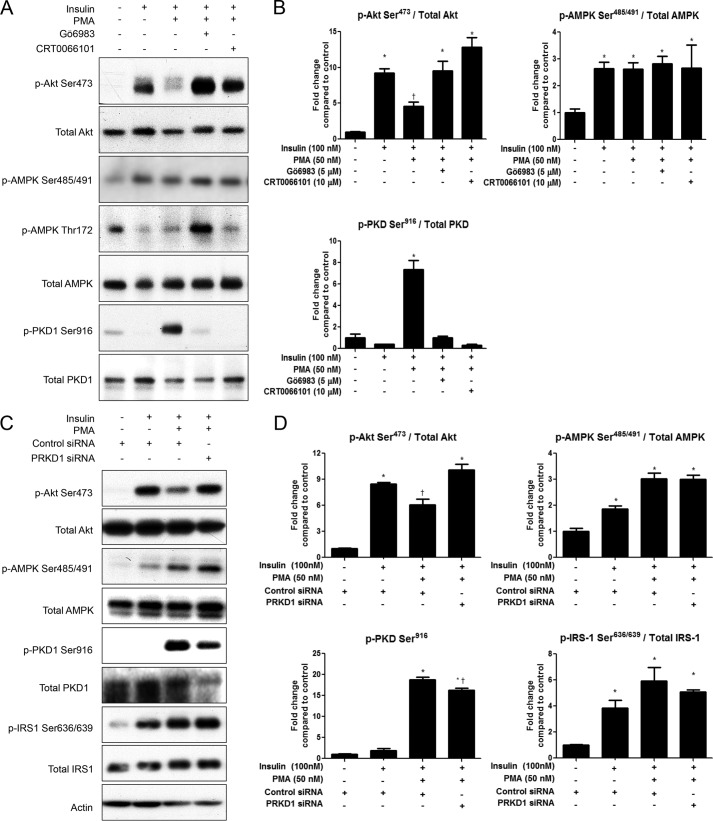

PMA Treatment Inhibits Insulin Signaling through Akt, which Is Attenuated by Pretreatment with Gö6983 or CRT0066101, or by PKD1 Knockdown

To test whether the PMA-induced changes were associated with impaired insulin signaling, we measured insulin-stimulated Akt phosphorylation. PMA treatment (50 nm) for 30 min diminished insulin-stimulated Akt Ser473 phosphorylation (Fig. 6, A and B). Pretreatment with Gö6983 or CRT0066101 restored insulin signaling through Akt. Since both insulin and PMA independently stimulate AMPK Ser485/491 phosphorylation through Akt and PKD, respectively, all combinations of insulin and PMA with and without inhibitors significantly increased serine phosphorylation of AMPK (Fig. 6, A and B). Similarly, siRNA mediated knockdown of PKD1 also restored insulin signaling through Akt (Fig. 6, C and D). PKD1 knockdown, however, did not prevent PMA-induced serine phosphorylation of IRS-1, which is known to impair insulin signaling. Thus, this suggests that PKD1 activation impairs insulin signaling through a novel mechanism, independent of IRS-1 phosphorylation.

FIGURE 6.

PMA stimulates PKD1 to impair insulin signaling. A and B, C2C12 myotubes were treated with or without Gö6983 (5 μm) or CRT0066101 (10 μm) for 1h prior to PMA treatment (50 nm, 30 min), followed by insulin stimulation (100 nm, 15min). C and D, C2C12 myotubes were transfected with scrambled or PKD1 siRNA. 48 h later, they were treated with PMA (50 nm, 30 min), followed by insulin stimulation (100 nm, 15 min). Cells were lysed, and Akt, AMPK, PKD1, and IRS-1 phosphorylation were analyzed by Western blot. Representative blots (A, C) and quantifications (B, D) are shown. *, p < 0.05 compared with control; †, p < 0.05 compared with insulin treatment.

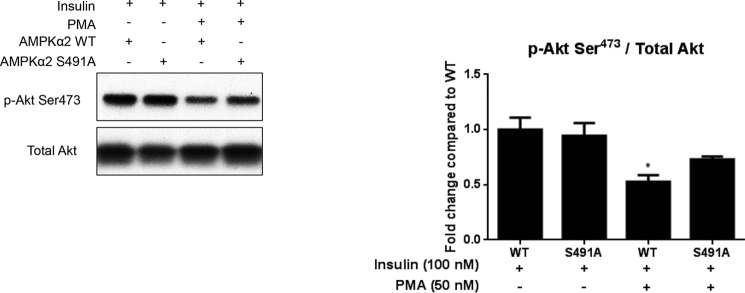

Expression of S491A AMPKα2 Prevents PMA-induced Impairments in Insulin-signaling through Akt

To evaluate whether AMPK was involved in the diminished insulin-stimulated Akt phosphorylation following PMA treatment, we transfected cells with phosphodefective S491A AMPKα2. While PMA treatment significantly reduced insulin-stimulated Akt Ser473 phosphorylation in cells expressing WT AMPKα2, this effect was not seen in cells expressing the phosphodefective AMPKα2 (Fig. 7). These data suggest that AMPK Ser491 is required for PMA to impair insulin signaling through Akt.

FIGURE 7.

Expression of S491A AMPKα2 prevents the PMA-induced impairment in insulin signaling through Akt. C2C12 cells were transfected with WT AMPKα2 or S491A AMPKα2. 48 h later, cells were treated with PMA (50 nm, 30 min) followed by insulin stimulation (100 nm, 15 min). Cells were then lysed, and Akt phosphorylation at Ser473 was analyzed by Western blot. A representative blot and quantification are shown. Results are means ± S.E. (n = 3–6 per treatment). *, p < 0.05 compared with WT + insulin.

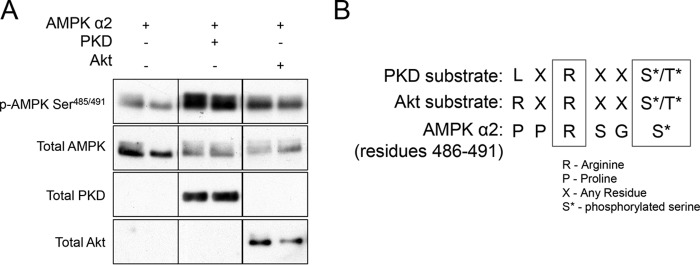

Recombinant PKD1 Phosphorylates AMPKα2 at Ser491 in Cell-free Conditions

To determine if PKD1 directly phosphorylates AMPK or if an intermediate signaling molecule is necessary, we tested whether recombinant PKD1 phosphorylates AMPK in a cell-free system. Compared with AMPKα2 alone, co-incubation of recombinant PKD1 with AMPKα2 caused phosphorylation of AMPKα2 at Ser491 (Fig. 8A). Incubation of Akt, used as a positive control, with AMPK also caused an obvious increase in Ser491 phosphorylation. These data suggest that PKD1 phosphorylates AMPK directly. To evaluate whether AMPKα2 Ser491 is a good substrate for PKD1, we lined up the PKD1 substrate consensus sequence with the sequence of residues preceding Ser491 on AMPKα2. Although AMPKα2 has a proline rather than PKD1 preferred leucine at the −5 position, the arginine at the −3 position does line up (Fig. 8B). This is similar to Akt, which prefers arginine at both the −5 and −3 positions.

FIGURE 8.

Recombinant PKD1 phosphorylates AMPK at Ser485/491 in a cell-free assay. Recombinant AMPKα2/β1/γ1 was incubated with recombinant PKD1 or recombinant Akt as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Phosphorylation of AMPK at Ser491 was evaluated by Western blot. Representative image shown is from a single gel/exposure. A, consensus substrate motifs of PKD and Akt were lined up with residues 486–491 of AMPKα2 (B). n = 3 per group. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Discussion

A better understanding of how AMPK is regulated at a molecular level is important for improving drug-targeting strategies for T2D. Phosphorylation of AMPK at Thr172 of the activation loop is generally held to be essential for the activation of AMPK and is often used as a readout for its activity. However, our data add to a growing number of studies showing that phosphorylation of AMPK at Ser485/491 can inhibit AMPK activity, even in the absence of changes in p-AMPK Thr172 (4, 5). These data suggest that phosphorylation of AMPK at Ser485/491 can inhibit AMPK activity independent of changes in p-AMPK Thr172 and that inhibition of p-AMPK Thr172 is not required for Ser485/491 phosphorylation to induce inhibition of AMPK activity. We also show, for the first time, that PKD1 activation can stimulate phosphorylation of AMPK Ser485/491 in skeletal muscle cells, resulting in impaired insulin signaling. In addition to identifying a novel kinase that can inhibit AMPK via Ser485/491 phosphorylation, these studies present a possible mechanism by which AMPK may be inhibited by excess nutrients, since DAG (which activates PKD1) is known to be increased by high glucose and lipids.

In 2012, Tsuchiya et al. (22) demonstrated that 60 min of PMA treatment (1 μm) inhibits AMPK activity by ∼33% in cardiac myocytes, as measured by the SAMS peptide assay. They found that this inhibition could be prevented by the nonspecific PKC inhibitor bisindoylmaleimide I (BIM I) and by the ERK inhibitor U0126, which led them to conclude that PMA inhibits AMPK by a mechanism involving the PKC and ERK pathways. There was no apparent change in energy state (AMP/ATP ratio) accompanying this decrease in AMPK activity. To our knowledge, this was the first report of PMA treatment causing inhibition of AMPK; however, AMPK phosphorylation at Thr172 or Ser485/491 was not measured. In concert with these results, we found that PMA treatment significantly diminished AMPK activity in C2C12 myotubes (Fig. 3A, 3C). However, we found that a dose of only 50 nm for 30min resulted in a 50–60% decrease in AMPK activity, nearly twice as much as was seen in the cardiac myocytes. In addition, our results indicate that ERK was not involved in the phosphorylation of AMPK at Ser485/491 induced by PMA. These discrepancies could be due to differences in cell type or methodologies.

Several kinases have been reported to phosphorylate AMPK at Ser485/491. We (4) and others (7) have shown that Akt phosphorylates and inhibits AMPK at this site in muscle, liver, and heart in response to insulin. In the hypothalamus, the mTOR/p70S6 kinase pathway has been reported to cause this inhibitory event in response to leptin (5), an effect shown to be essential for mediating the anorectic effects of leptin. In murine macrophage-like RAW 264.7 cells, Park et al. (12) showed that IKKβ phosphorylates AMPK at Ser485 in response to LPS treatment in mature dendritic cells. ERK1/2 was recently shown to phosphorylate AMPK on this serine residue (13), an effect that may be an important part of the mechanism by which CCR7 signaling promotes cell survival. Furthermore, protein kinase A (PKA) has been reported to act as an upstream kinase for AMPK Ser485/491 in INS-1 cells in response to forskolin or GIP stimulation (14) and in human diploid fibroblasts in response to lysophosphatidic acid (15). We ruled out Akt, S6K, and ERK as upstream kinases responsible for AMPK Ser485/491 phosphorylation in response to PMA treatment (Fig. 5); however, we have identified PKD1 as a novel enzyme to be added to the growing list of kinases which inhibit AMPK via Ser485/491 phosphorylation. Furthermore, we found a significant inverse correlation between AMPK activity and phosphorylation at Ser485/491 under these conditions, suggesting that PKD1 is responsible for the serine phosphorylation and inhibition of AMPK in this setting (Fig. 3, B and D). The fact that expression of a phosphodefective S491A AMPKα2 mutant prevented the PMA-induced reduction in AMPKα2 activity confirms that phosphorylation of AMPKα2 on Ser491 is required for PMA-induced inhibition of AMPK kinase activity.

Many of the aforementioned kinases that can mediate AMPK inhibition through Ser485/491 phosphorylation are associated with anabolic or pro-hypertrophic signaling pathways (Akt, mTOR/P70S6K). This is not surprising, since AMPK is generally activated under low energy conditions that favor catabolic processes, and inhibited under conditions of energy overload that favor anabolic processes. Consistent with this, PKD1 has recently been identified as having pro-hypertrophic functions. For example, Harrison et al. (21) reported that transgenic mice expressing a cardiac-specific, constitutively active PKD1 mutant develop cardiac hypertrophy, followed by ventricular chamber dilation, wall thinning, and contractile dysfunction. They also showed that PKD1 expression and activity are significantly increased in the myocardium of spontaneously hypertensive rats with heart failure, an effect that is further exaggerated by thoracic aortic banding. Furthermore, PKD1 activation was found to be elevated in hearts of humans with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy (20). While these results suggest that PKD1 activation may be sufficient to induce pathological cardiac remodeling, the role of PKD1 in skeletal muscle is less clear. McGee et al. (25) reported that loss of AMPK in muscle resulted in no change in HDAC5 phosphorylation during exercise, but a ∼33% compensatory increase in PKD activation, suggesting potential redundancies in the functions of these two proteins in response to exercise. Although they did not investigate the effects of PKD loss or activation on AMPK activation, these data, together with our results, suggest that PKD and AMPK may negatively regulate each other in skeletal muscle.

Further evidence supporting potential redundancy of functions between AMPK and PKD1, at least in regards to HDAC5 phosphorylation in response to exercise, is the fact that mice overexpressing constitutively active PKD1 in skeletal muscle show resistance to fatigue in response to repetitive contraction and a shift to Type I and Type IIa muscle fibers (26), while expression of a dominant negative kinase dead PKD1 in skeletal muscle results in impaired running performance and prevents fiber type switching (27). Similarly, it has long been known that AMPK mediates many adaptations of muscle to exercise (28), and loss of AMPK in muscle causes impairments in running capacity (29).

Our data showed that PKD1 activation impairs insulin-signaling through Akt in C2C12 myotubes, an effect prevented both by pharmacological inhibition and by genetic knockdown of PKD1 (Fig. 6). PKC activation by PMA is known to impair insulin signaling by causing serine phosphorylation of IRS-1. Intriguingly, PKD1 knockdown did not reduce PMA-induced serine phosphorylation of IRS-1, despite restoring insulin-stimulated Akt phosphorylation. These data suggest that PKD1 activation impairs insulin-signaling through an IRS-1-independent mechanism, although the exact mechanism remains to be determined. Additionally, we have shown that AMPKα2 Ser491 is required for the observed impairment in insulin signaling, though further studies are required to identify the exact mechanism (Fig. 7). Although AMPKα2 is the predominant isoform in skeletal muscle, the presence of AMPKα1 Ser485 could explain why Akt phosphorylation is not fully restored to control levels. The present study is the first report of PKD1 activation causing impaired insulin-signaling, and the mechanism by which it does so requires further investigation, though we have shown that it involves AMPK.

In summary, we have reported a novel inhibitory relationship between PKD1 and AMPK in skeletal muscle cells whereby PKD1 inhibits AMPK directly by phosphorylating it at Ser491 of the α2 subunit. Since PKD1 may be activated directly by DAG (or the DAG mimetic PMA) or by novel PKC isoforms, we have not ruled out the possibility that novel PKC isoforms may also be involved upstream of PKD1 in these processes. Similarly, though we have shown that PKD1 activation is necessary for the inhibition of AMPK and that AMPKα2 Ser491 is required for the impairment of insulin signaling through Akt, further studies are required to further elucidate the pathway responsible for this impairment. Our data suggest that PKD1 inhibition may be a novel strategy for preventing AMPK inhibition and impaired insulin sensitivity in muscle; however, based on the growing list of PKD1 functions in a variety of tissues being reported in the literature, this strategy would have to be approached with caution, and likely in a highly controlled, tissue-specific manner.

Author Contributions

K. A. C. and R. J. V. designed, performed, and analyzed the experiments, and K. A. C. wrote the manuscript. K. A. and B. S. S. provided technical assistance in performing experiments and preparation of figures. N. B. R. and A. K. S. helped with experimental design and editing of the manuscript. Y. D. provided reagents and technical guidance for data shown in Figs. 3 and 6. BBK edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

This study was supported by USPHS Grants RO1DK19514, RO1DK67509 (to N. B. R. and A. K. S.), NIH Training Grants NHLBI 2 T32 HL07969-06A1 (to K. A. C.) and 5T32HL007224 (to R. J. V.) NIH Grant R01 DK098002 and a Grant from the JPB foundation (to B. B. K.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

- T2D

- type 2 diabetes

- FFA

- free fatty acid; diacylglycerol

- PMA

- phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate

- CaMK

- calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase

- AMPK

- AMP-activated protein kinase

- ACC

- acetyl-CoA carboxylase.

References

- 1. Amati F. (2012) Revisiting the diacylglycerol-induced insulin resistance hypothesis. Obes Rev. 13, 40–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. IDF. (2014) International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, 6th Edn update (Federation I. D., ed), Brussels, Belgium [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kahn B. B., Alquier T., Carling D., and Hardie D. G. (2005) AMP-activated protein kinase: ancient energy gauge provides clues to modern understanding of metabolism. Cell Metab. 1, 15–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Valentine R. J., Coughlan K. A., Ruderman N. B., and Saha A. K. (2014) Insulin inhibits AMPK activity and phosphorylates AMPK Ser through Akt in hepatocytes, myotubes and incubated rat skeletal muscle. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 562, 62–69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dagon Y., Hur E., Zheng B., Wellenstein K., Cantley L. C., and Kahn B. B. (2012) p70S6 kinase phosphorylates AMPK on serine 491 to mediate leptin's effect on food intake. Cell Metab. 16, 104–112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hawley S. A., Ross F. A., Gowans G. J., Tibarewal P., Leslie N. R., and Hardie D. G. (2014) Phosphorylation by Akt within the ST loop of AMPK-alpha1 down-regulates its activation in tumour cells. Biochem. J. 459, 275–287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Horman S., Vertommen D., Heath R., Neumann D., Mouton V., Woods A., Schlattner U., Wallimann T., Carling D., Hue L., and Rider M. H. (2006) Insulin antagonizes ischemia-induced Thr172 phosphorylation of AMP-activated protein kinase α-subunits in heart via hierarchical phosphorylation of Ser485/491. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 5335–5340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Coughlan K. A., Balon T. W., Valentine R. J., Petrocelli R., Schultz V., Brandon A., Cooney G. J., Kraegen E. W., Ruderman N. B., and Saha A. K. (2015) Nutrient excess and AMPK downregulation in incubated skeletal muscle and muscle of glucose infused rats. PloS one 10, e0127388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Garcia-Haro L., Garcia-Gimeno M. A., Neumann D., Beullens M., Bollen M., and Sanz P. (2012) Glucose-dependent regulation of AMP-activated protein kinase in MIN6 beta cells is not affected by the protein kinase A pathway. FEBS Letts. 586, 4241–4247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ning J., Xi G., and Clemmons D. R. (2011) Suppression of AMPK activation via S485 phosphorylation by IGF-I during hyperglycemia is mediated by AKT activation in vascular smooth muscle cells. Endocrinology 152, 3143–3154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Berggreen C., Gormand A., Omar B., Degerman E., and Göransson O. (2009) Protein kinase B activity is required for the effects of insulin on lipid metabolism in adipocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 296, E635–E646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Park D. W., Jiang S., Liu Y., Siegal G. P., Inoki K., Abraham E., and Zmijewski J. W. (2014) GSK3β-dependent inhibition of AMPK potentiates activation of neutrophils and macrophages and enhances severity of acute lung injury. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 307, L735–L745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. López-Cotarelo P., Escribano-Diaz C., González-Bethencourt I. L., Gómez-Moreira C., Deguiz M. L., Torres-Bacete J., Gómez-Cabanas L., Fernández-Barrera J., Delgado-Martín C., Mellado M., Regueiro J. R., Miranda-Carús M. E., and Rodríguez-Fernández J. L. (2015) A Novel MEK-ERK-AMPK signaling axis controls chemokine receptor CCR7-dependent Survival in human mature dendritic cells. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 827–840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hurley R. L., Barré L. K., Wood S. D., Anderson K. A., Kemp B. E., Means A. R., and Witters L. A. (2006) Regulation of AMP-activated protein kinase by multisite phosphorylation in response to agents that elevate cellular cAMP. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 36662–36672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rhim J. H., Jang I. S., Song K. Y., Ha M. K., Cho S. C., Yeo E. J., and Park S. C. (2008) Lysophosphatidic acid and adenylyl cyclase inhibitor increase proliferation of senescent human diploid fibroblasts by inhibiting adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase. Rejuvenation Res. 11, 781–792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bollag G. E., Roth R. A., Beaudoin J., Mochly-Rosen D., and Koshland D. E. Jr. (1986) Protein kinase C directly phosphorylates the insulin receptor in vitro and reduces its protein-tyrosine kinase activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 83, 5822–5824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Avkiran M., Rowland A. J., Cuello F., and Haworth R. S. (2008) Protein kinase D in the cardiovascular system: emerging roles in health and disease. Circ. Res. 102, 157–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Johannes F. J., Prestle J., Eis S., Oberhagemann P., and Pfizenmaier K. (1994) PKCu is a novel, atypical member of the protein kinase C family. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 6140–6148 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. LaValle C. R., George K. M., Sharlow E. R., Lazo J. S., Wipf P., and Wang Q. J. (2010) Protein kinase D as a potential new target for cancer therapy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1806, 183–192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bossuyt J., Helmstadter K., Wu X., Clements-Jewery H., Haworth R. S., Avkiran M., Martin J. L., Pogwizd S. M., and Bers D. M. (2008) Ca2+/Calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IIδ and protein kinase D overexpression reinforce the histone deacetylase 5 redistribution in heart failure. Circ. Res. 102, 695–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Harrison B. C., Kim M. S., van Rooij E., Plato C. F., Papst P. J., Vega R. B., McAnally J. A., Richardson J. A., Bassel-Duby R., Olson E. N., and McKinsey T. A. (2006) Regulation of cardiac stress signaling by protein kinase d1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 3875–3888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tsuchiya Y., Denison F. C., Heath R. B., Carling D., and Saggerson D. (2012) 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase is inactivated by adrenergic signalling in adult cardiac myocytes. Biosci. Rep. 32, 197–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Park H., Kaushik V. K., Constant S., Prentki M., Przybytkowski E., Ruderman N. B., and Saha A. K. (2002) Coordinate regulation of malonyl-CoA decarboxylase, sn-glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase, and acetyl-CoA carboxylase by AMP-activated protein kinase in rat tissues in response to exercise. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 32571–32577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Saha A. K., Xu X. J., Lawson E., Deoliveira R., Brandon A. E., Kraegen E. W., and Ruderman N. B. (2010) Downregulation of AMPK accompanies leucine- and glucose-induced increases in protein synthesis and insulin resistance in rat skeletal muscle. Diabetes 59, 2426–2434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. McGee S. L., Swinton C., Morrison S., Gaur V., Campbell D. E., Jorgensen S. B., Kemp B. E., Baar K., Steinberg G. R., and Hargreaves M. (2014) Compensatory regulation of HDAC5 in muscle maintains metabolic adaptive responses and metabolism in response to energetic stress. Faseb. J. 28, 3384–3395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kim M. S., Fielitz J., McAnally J., Shelton J. M., Lemon D. D., McKinsey T. A., Richardson J. A., Bassel-Duby R., and Olson E. N. (2008) Protein kinase D1 stimulates MEF2 activity in skeletal muscle and enhances muscle performance. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28, 3600–3609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ellwanger K., Kienzle C., Lutz S., Jin Z. G., Wiekowski M. T., Pfizenmaier K., and Hausser A. (2011) Protein kinase D controls voluntary-running-induced skeletal muscle remodelling. Biochem. J. 440, 327–335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Richter E. A., and Ruderman N. B. (2009) AMPK and the biochemistry of exercise: implications for human health and disease. Biochem. J. 418, 261–275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. O'Neill H. M., Maarbjerg S. J., Crane J. D., Jeppesen J., Jørgensen S. B., Schertzer J. D., Shyroka O., Kiens B., van Denderen B. J., Tarnopolsky M. A., Kemp B. E., Richter E. A., and Steinberg G. R. (2011) AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) β1β2 muscle null mice reveal an essential role for AMPK in maintaining mitochondrial content and glucose uptake during exercise. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 16092–16097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]