Abstract

Exopeptidases, including dipeptidyl- and tripeptidylpeptidase, are crucial for the growth of Porphyromonas gingivalis, a periodontopathic asaccharolytic bacterium that incorporates amino acids mainly as di- and tripeptides. In this study, we identified a novel exopeptidase, designated acylpeptidyl oligopeptidase (AOP), composed of 759 amino acid residues with active Ser615 and encoded by PGN_1349 in P. gingivalis ATCC 33277. AOP is currently listed as an unassigned S9 family peptidase or prolyl oligopeptidase. Recombinant AOP did not hydrolyze a Pro-Xaa bond. In addition, although sequence similarities to human and archaea-type acylaminoacyl peptidase sequences were observed, its enzymatic properties were apparently distinct from those, because AOP scarcely released an N-acyl-amino acid as compared with di- and tripeptides, especially with N-terminal modification. The kcat/Km value against benzyloxycarbonyl-Val-Lys-Met-4-methycoumaryl-7-amide, the most potent substrate, was 123.3 ± 17.3 μm−1 s−1, optimal pH was 7–8.5, and the activity was decreased with increased NaCl concentrations. AOP existed predominantly in the periplasmic fraction as a monomer, whereas equilibrium between monomers and oligomers was observed with a recombinant molecule, suggesting a tendency of oligomerization mediated by the N-terminal region (Met16–Glu101). Three-dimensional modeling revealed the three domain structures (residues Met16–Ala126, which has no similar homologue with known structure; residues Leu127–Met495 (β-propeller domain); and residues Ala496–Phe736 (α/β-hydrolase domain)) and further indicated the hydrophobic S1 site of AOP in accord with its hydrophobic P1 preference. AOP orthologues are widely distributed in bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes, suggesting its importance for processing of nutritional and/or bioactive oligopeptides.

Keywords: aminopeptidase, microbial pathogenesis, oligomerization, peptidase, periodontal disease, DFP-6, acylaminoacyl peptidase, oligopeptidase B

Introduction

Porphyromonas gingivalis, a Gram-negative obligate anaerobe, has been implicated as the causative agent of chronic periodontal disease (1, 2), which is a major reason for permanent tooth loss (3–5). Recently, much attention has been paid to this bacterium due to its association with systemic diseases, such as cardiovascular disorders (6), decreased kidney function (7), and rheumatoid arthritis (8). P. gingivalis does not ferment carbohydrates but rather metabolizes amino acids to produce ATP by a putative respiratory chain of fumarate respiration without oxygen (9). In addition, it incorporates nutritional amino acids not as single amino acids but preferentially as di- and tripeptides and short oligopeptides, possibly via inner membrane-associated oligopeptide transporters (9, 10).

In P. gingivalis, extracellular nutritional proteins are initially digested to oligopeptides by potent cysteine endopeptidases, such as Arg-gingipain (Rgp)3 (C25.001 in MEROPS classification) (11) and Lys-gingipain (Kgp) (C25.002) (12), and subsequently degraded into di- and tripeptides by exopeptidases (i.e. dipeptidylpeptidases (DPPs) (13–16) and prolyl tripeptidylpeptidase A (PTP-A) (17), respectively). Therefore, the topology of the subcellular localization of these peptidases (i.e. extracellular and outer membrane-bound Rgp/Kgp and DPPs/PTP-A in the periplasmic space) appears to be suitable for an ordered degradation of proteinaceous substrates and their incorporation into cells. Through amino acid metabolism, the organism excretes sulfide, ammonia, butyrate (18, 19), and methyl mercaptan (20) as end products, which have been suggested to cause host tissue damage (21–23). Accordingly, DPPs, PTP-A, and gingipains are considered to play crucial roles not only in cell growth but also bacterial pathogenicity.

Thus far, four DPPs (i.e. DPP4, DPP5, DPP7, and DPP11) have been identified in P. gingivalis. These are serine peptidases belonging to either the S9 or S46 family, with DPP4 (S09.003) showing a preference for Pro at P1 (13, 14) and DPP5 (S09.012), the first entity identified in bacteria, showing a preference for hydrophobic P1 residues and no specificity at the P2 position (24). Furthermore, DPP7 (S46.001) has a hydrophobic preference for the P1 (15, 25) as well as P2 (26) positions, whereas we discovered that DPP11 (S46.002) is a unique DPP specific for acidic P1 residues (Asp and Glu) (27). In addition to these DPPs, P. gingivalis possesses a metallopeptidase encoded by the gene PGN_1645, which was identified as DPP3 (M49.001) and specific for P1 Arg. However, DPP3 appears to be localized in the cytosol, whereas the Arg-specific DPP activity of Rgp plays a role in extracellular substrate processing (24). We also found Lys-specific DPP activity in Kgp (24). DPPs do not cleave polypeptides with Pro at the third position from the N terminus, whereas PTP-A (S09.017) is able to release the N-terminal tripeptide Xaa1-Xaa2-Pro3 (16, 17). Therefore, most extracellular polypeptides, at least those without N-terminal modification, should be sequentially and completely degraded into di- or tripeptides in P. gingivalis by the cooperative activities of the four DPPs, PTP-A, and gingipains (24).

On the other hand, our previous observations of P. gingivalis NDP212, a dpp4-5-7-11-knock-out strain, suggested the existence of an unidentified DPP responsible for Met-Leu-MCA hydrolysis because the activity was markedly elevated in the mutant strain as compared with a dpp4-5-7-knock-out strain (24). In order to define this entity, we focused on and studied the three remaining uncharacterized putative S9 family proteins (i.e. PGN_1349, PGN_1542, and PGN_1878) of P. gingivalis in the present study. We found peptidase activity exclusively in PGN_1349, and, interestingly, most exopeptidase activities remaining in NDP212 were explained by the activity of PGN_1349. The observed peptidase properties of PGN_1349 indicated it as a novel oligopeptidase, designated acylpeptidyl oligopeptidase (AOP), with a preference for hydrophobic amino acids at the P1 position of its substrates, especially those with N-terminal modification.

Experimental Procedures

Materials

pQE60 (Qiagen Inc., Chatsworth, CA) and pTrcHis2-TOPO (Invitrogen) were used as expression vectors. Restriction enzymes and DNA-modifying enzymes were purchased from Takara Bio (Tokyo, Japan) and New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA), respectively. Quick TaqHS DyeMix and KOD-Plus-Neo DNA polymerase came from Toyobo (Tokyo, Japan). Met-Leu-4-methycoumaryl-7-amide (MCA) was from Bachem (Bubendorf, Switzerland), and Leu-Asp-, Leu-Glu-, Lys-Met-, benzyloxycarbonyl (Z)-Lys-Met-, and Z-AVKM-MCA were synthesized by Thermo Fisher Scientific (Ulm, Germany) and Scrum (Tokyo, Japan). Other MCA peptides were purchased from the Peptide Institute (Osaka, Japan). Oligonucleotide primers were synthesized by FASMAC (Atsugi, Japan). Low molecular weight markers, full-range rainbow molecular weight markers, rabbit muscle aldolase, egg white ovalbumin, and Sephacryl S-200 High Resolution and Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 columns were from GE Healthcare (Little Chalfont, UK). Bovine liver catalase and bovine milk α-lactalbumin were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Lysozyme from egg white and formyl cellulofine were from Seikagaku Biobusiness Corp. (Tokyo, Japan).

Culture Conditions

P. gingivalis strains ATCC 33277, KDP136 (28), NDP212 (24), and NDP600 were grown anaerobically (80% N2, 10% CO2, 10% H2) in enriched brain-heart infusion broth (BD Biosciences) supplemented with 5 μg/ml hemin and 0.5 μg/ml menadione. Ampicillin (10 μg/ml) for NDP600 and appropriate antibiotics (ampicillin, erythromycin, tetracycline, and chloramphenicol) were added to the cultures of KDP136 and NDP212, as described previously (24, 27). Bacterial cells were suspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at pH 7.4 and then centrifuged at 6000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. The cell pellet was washed once with PBS, resuspended in PBS to adjust absorbance to 2.0 at 600 nm, and then used in the following experiments.

Expression and Purification of Recombinant Proteins

Oligonucleotides and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. DNA fragments encoding the mature forms (Met16–Lys579) of PGN_1349 (29) (GenBankTM accession number 6329856, MEROPS code MER034614) and Leu6–Glu279 of PGN_1542 (MER110015) were amplified by PCR using sets of primers (primers 5PGN1349-M16 and 3PGN1349-K759B and primers 5PGN1542-L6Bam and 3PGN1542-E279Bam, respectively), with genomic DNA of P. gingivalis ATCC 33277 utilized as a template. The PCR products were ligated with pTrcHis2-TOPO according to the manufacturer's protocol, resulting in production of pTrcHis2-PGN1349 and -PGN1542, respectively. A DNA fragment encoding Ile6–Leu473 of PGN_1878 (MER109588) was PCR-amplified using a set of primers (5PGN1878-I6Bgl and 3PGN1878-L473Bgl). After restriction cleavage by BglII, the fragment was inserted into the BamHI site of pQE60, resulting in production of pQE60-PGN1878. A deletion mutation of Met16–Gly101 (designated pTrcHis2-PGN1349-N102) was constructed using a PCR-based technique with primers 5PGN1349-N102 and 3pTrcHisTopo-L-1, with the substitution of Ser615 by Ala (designated pTrcHis2-PGN1349-S615A and pTrcHis2-PGN1349-N102-S615A) constructed from pTrcHis2-PGN1349 and pTrcHis-PGN1349-N102 using the primers 5PGN1349-S615A and 3PGN1349-A614, respectively. Mutations were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

TABLE 1.

Primers, plasmids, and DNA fragments used in this study

Restriction and mutated sites are shown in italic type and underlined, respectively.

| Name | Sequence (5′–3′) | Product (plasmid or DNA fragment) |

|---|---|---|

| 5PGN1349M16 | ATGACTGTGCATGCACAAAAGATCA | pTrcHis2TOPO-PGN1349 |

| 3PGN1349-K759B | TTTCTTCAGGTGTTTGGCGAAGAAACC | pTrcHis2TOPO-PGN1349 |

| 5PGN1542-L6Bam | AAAAAAGGATCCCTACAGATCATCATACTGCT | pQE60-PGN1542 |

| 3PGN1542-E279Bam | AGATCTGGATCCTTCTACCTGAGATTCGATGT | pQE60-PGN1542 |

| 5PGN1878-I6Bgl | AAGCATAGATCTATTATTATCATCTAATGTAGT | pQE60-PGN1878 |

| 3PGN1878-L473Bgl | AGATCTAGATCTAAGACTATCCAGGAAGGAGC | pQE60-PGN1878 |

| 5PGN1349-N102 | AATGTGGAGCAGATGGGCTTCAGCCT | pTrcHis2TOPO-PGN1349-N102 |

| 3pTrcHisTopo-L-1 | AAGGGCCATGGTTTATTCCTCCTTAT | pTrcHis2TOPO-PGN1349-N102 |

| 5PGN1349-S615A | GCCCACGGTGGTTATGCCACGCTGAT | pTrcHis2TOPO-PGN1349-S615A |

| 3PGN1349-A614 | GGCACCGTATATGGCGATCCTGTCGG | pTrcHis2TOPO-PGN1349-N102-S615A |

| 1349-5F1 | ATAATCACCCAACAAAATACCAAGT | PGN1349 5′ region with cepA anchor |

| cep-comp-1349-5R | TGCTTCACACCATGGATATGATCATGTAGTCCTTC | PGN1349 5′ region with cepA anchor |

| 1349-5F1-cepF | ATCATATCCATGGTGAAGCATCTTCGATGCTG | cepA with 5PGN1349 anchor |

| 1349-3Fcomp-cep3R-comp | ATTGTTTTTGTTCCGATAGTGATAGTGAACGG | cepA with 5PGN1349 anchor |

| cep-3F-1349-3F1 | TCACTATCGGAACAAAAACAATCCGCAGATCTTCGA | 5PGN1349 3′ region with cepA anchor |

| 1349-3Rcomp | GCTTTCAGCCTTATATCCTCCGGCTTA | 5PGN1349 3′ region with cepA anchor |

| 1349-5F2 | ATGACTGTGCATGCACAAAAGATCA | 5PGN1349-cepA |

| 1349-3R2comp | TTTCTTCAGGTGTTTGGCGAAGAAACC | 5PGN1349-cepA |

Escherichia coli XL-1 Blue cells carrying expression plasmids were cultured in Luria-Bertani broth supplemented with 75 μg/ml ampicillin at 37 °C. Recombinant proteins were induced with 0.2 mm isopropyl-thiogalactopyranoside at 30 °C for 4 h and then purified using Talon affinity chromatography as reported previously (27).

Disruption of P. gingivalis Genes

P. gingivalis NDP212, with deletion of four DPP genes (dpp4, dpp5, dpp7, and dpp11) (24), and KDP136, with deletions of kgp, rgpA, and rgpB (28), were reported previously. To construct the PGN_1349 gene deletion mutant, DNA fragments of each 5′- and 3′-part of the PGN_1349 gene were PCR-amplified with a set of primers (1349-5F1 and cep-comp-1349-5R for the 5′ part, cep3F-1349–3F1 and 1349–3Rcomp for the 3′ part). A cepA fragment was amplified using primers (1349-5F1-cepF and 1349-3Fcomp-cep3R-comp) and pCR4-TOPO as a template. Nested PCR was performed with a mixture of these three fragments using primers (1349-5F2 and 1349-3R2comp), and then the obtained DNA fragment (3440 bp) was introduced into P. gingivalis by electroporation, resulting in NDP600 (pgn1349::cepA).

Measurement of Peptidase Activity

Peptidase activity was measured using peptidyl-MCA as reported previously (24, 27). Briefly, the reaction was started by the addition of recombinant proteins (5–100 ng), a periplasmic cell fraction (1–5 μl), or P. gingivalis cell suspensions (1–5 μl) in a reaction mixture (200 μl) composed of 50 mm sodium phosphate (pH 7.5), 5 mm EDTA, and 20 μm peptidyl-MCA. After 30 min at 37 °C, fluorescence intensity was measured with excitation at 380 nm and emission at 460 nm. In some experiments, pH values varied from 5.5 to 9.5 with 50 mm phosphate (pH 5.5–8.5) or Tris-HCl (pH 7.0–9.5), and NaCl concentrations varied from 0 to 1.6 m. To determine enzymatic parameters, recombinant proteins were incubated with various concentrations of peptidyl-MCA. The data obtained were analyzed using a nonlinear regression curve fitted to the Michaelis-Menten equation with GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA). Values are shown as the average ± S.D. and are calculated from four independent measurements.

Subcellular Fractionation

All procedures were carried out at 4 °C according to a method reported previously (30), with a sight modification. Briefly, a 20-ml culture of P. gingivalis in the log phase was centrifuged at 6000 × g for 15 min, and then the extracellular fraction was obtained from the supernatant by filtration with a 0.20-μm membrane filter. Bacterial cells were washed with ice-cold PBS, resuspended in 4 ml of 0.25 m sucrose in 5 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), and then left on ice for 10 min. Cells were precipitated at 12,500 × g for 15 min, resuspended in 4 ml of 5 mm Tris-HCl, and mixed gently for 10 min to disrupt the outer membrane. The supernatant was obtained by centrifugation at 6000 × g for 15 min and collected as the periplasmic fraction containing the outer membrane. The obtained spheroplasts as precipitate were resuspended in PBS and then disrupted in an ice-water bath by sonication pulse 10 times for 10 s each with 2-s intervals. The cytosol and inner membrane fractions were separately prepared by ultracentrifugation, as described previously (24).

Size Exclusion HPLC

Recombinant proteins and the periplasmic fraction were subjected to size exclusion HPLC using ÄKTA explorer 10S (GE Healthcare) with a Superdex200 increase 10/300 column (1.5 × 30 cm) equilibrated with 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) containing 1 mm EDTA. They were separated with the identical buffer at a rate of 0.75 ml/min at room temperature, and then 0.5-ml fractions were collected. Aliquots of the fractions were subjected to a peptidase assay with Z-VKM-MCA as well as SDS-PAGE or native PAGE.

Immunoblotting Analysis

Recombinant PGN_1349 (Met16–Lys759) was purified by use of Talon affinity chromatography and further subjected to a Sephacryl S200 HR column equilibrated with 20 mm ammonium bicarbonate (pH 8.5). Rabbit anti-PGN_1349 (AOP) antiserum was prepared as reported previously (24, 27). For immunoblotting, separated proteins on polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore) were incubated with anti-AOP antiserum (103-fold dilution), followed by alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG. Finally, specific bands were visualized with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate and nitro blue tetrazolium. Similarly, immunoblotting against P. gingivalis DPP5 and DPP7 was performed as reported previously (24, 25).

N-Terminal Sequencing of Proteins

Proteins separated on SDS-PAGE and transferred to a Sequi-Blot membrane (Bio-Rad) were stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue and subjected to protein sequencing by use of a model Procise 49XcLC protein sequencer (Applied Biosystems).

Three-dimensional Homology Modeling

To search for an ideal template for homology modeling, the P. gingivalis AOP sequence was submitted to the Psipred server (31) using the GenThreader method (32) for domain and fold assignment. Afterward, a BLAST search (33) against the Protein Data Bank was performed to identify the closest homologue to P. gingivalis AOP with known three-dimensional structure. The model was generated via the Phyre2 server (Protein Homology/Analogy Recognition Engine) (34), using the tool “one-to-one threading,” in the expert mode. The coordinates of Pyrococcus horikoshii acylaminoacyl peptidase (AAP) (35) (Protein Data Bank code 4HXE) and the P. gingivalis AOP sequence were submitted to structural alignment and further model building. The final model covered around 85% of the sequence, sharing 20% identity with the template.

Results

PGN_1349 Responsible for Remaining Activity in NDP212

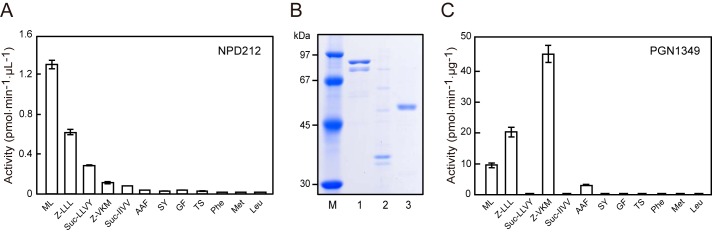

We previously reported that Met-Leu-MCA-hydrolyzing activity was markedly decreased in a dpp4-5-7 triple knock-out P. gingivalis strain (NDP211). However, unexpectedly, that activity was reversed by introduction of a fourth dpp gene disruption to NDP211, resulting in NDP212, a dpp4-5-7-11 quadruple knock-out strain (24). These results indicated that the bacterium additionally expresses a peptidase related to Met-Leu-MCA hydrolysis in addition to DPP5 and DPP7 and suggested an up-regulation mechanism to compensate for the loss of dipeptide production. To identify this entity, the peptidase activity of NDP212 was reexamined in detail with various MCA substrates (portion of results shown in Fig. 1A). NDP212 showed the most efficient hydrolysis of Met-Leu-MCA, followed by benzyloxycarbonyl (Z)-LLL-MCA and succinyl (Suc)-LLVY-MCA, suggesting that the candidate is not a DPP but probably an oligopeptidase with a hydrophobic P1 preference. These activities were observed in a cell-associated form and not with the culture supernatant and were efficiently inhibited by diisopropyl fluorophosphates, suggesting a serine peptidase, the same as previously reported periplasmic DPPs (data not shown).

FIGURE 1.

Peptidase activities remaining in dpp4-5-7-11 knock-out strain and recombinant PGN_1349. A, the peptidase activity of NDP212 cells (Δdpp4-5-7-11) was determined with peptidyl-MCA. B, purified proteins (0.5 μg) of PGN_1349 (lane 1), PGN_1542 (lane 2), and PGN_1878 (lane 3) were separated on SDS-polyacrylamide gels and detected by Coomassie Blue staining. Lane M, molecular weight marker. C, the peptidase activity of recombinant PGN_1349 was determined with peptidyl-MCA. Values are shown as the mean ± S.D. (error bars) (n = 3).

Taking into consideration these properties, along with information from the KEGG and MEROPS databases (29, 36), we focused on three uncharacterized peptidases among the seven S9 family members (i.e. PGN_1349 (KEGG definition: DPP), PGN_1542 (esterase), and PGN_1878 (hypothetical protein)) and expressed them as C-terminal His6-tagged proteins in E. coli. Purified PGN_1349, PGN_1542, and PGN_1878 migrated as 85-, 35-, and 50-kDa species, respectively, in accordance with their calculated molecular masses (Fig. 1B). Subsequent peptidase analysis using 80 peptidyl-MCAs available in our laboratory revealed that PGN_1349 hydrolyzed several substrates. In contrast, attempts to detect peptidase activities in PGN_1542 and PGN_1878 have not been successful to date.

PGN_1349 is currently annotated as a DPP, although it was found to be hydrolyzed by both N-terminally blocked and unblocked substrates, such as Met-Leu-, Z-LLL-, Z-VKM-, and AAF-MCA, to a small extent (Fig. 1C). Other substrates showed much lower activities, including glutalyl-AAF-MCA (4.21 ± 0.05 pmol/min/μg, mean ± S.D., n = 3), Suc-AAA-MCA (1.01 ± 0.05), N-methoxysuccinyl-AAP-MCA (0.38 ± 0.02), GP- (0.28 ± 0.01), Ac-Ala-MCA (0.12 ± 0.00), Lys-Ala-MCA (0.10 ± 0.00), Ac-Met-MCA (0.056 ± 0.002), Z-MEK-MCA (0.026 ± 0.005), Gly-Gly-MCA (0.017 ± 0.004), Z-LRGG-MCA (0.015 ± 0.000), Boc-FSR-MCA (0.013 ± 0.012), Z-LLE-MCA (0.009 ± 0.002), Ala-MCA (0.009 ± 0.000), and Leu-Asp-MCA (0.004 ± 0.002). These results indicate that PGN_1349 is not a DPP but rather an oligopeptidase that is able to liberate N-terminally blocked peptides with a P1 preference for hydrophobic residues. Interestingly, its substrate preference profile resembles that of NDP212, except for no activity of PGN_1349 against Suc-LLVY-MCA. In addition, NDP212 scarcely hydrolyzed Z-VKM-MCA, whereas PGN_1349 showed efficient hydrolysis. We speculated that the reason for the low level of Z-VKM-MCA hydrolysis by NDP212 was due to the activity of Kgp, which preceded the hydrolysis of Z-VKM-MCA into Z-Val-Lys and Met-MCA, in which the latter was scarcely degraded by PGN_1349 (Fig. 1C). In fact, the level of hydrolysis of Z-VKM-MCA was even higher than that of Z-LLL-MCA by the gingipain-null strain KDP136 (data not shown). At this time, we are unable to explain the activity against Suc-LLVY-MCA in NPD212, although it may be due to an unidentified peptidase. Taken together, we concluded that most hydrolyzing activities observed in NDP212 can be mainly attributed to PGN_1349.

Distribution of PGN_1349 Orthologues in Organisms

PGN_1349 in P. gingivalis ATCC 33277 and its homologues in other P. gingivalis strains have been annotated under various names, such as DPP (ATCC 33277) (29), prolyl oligopeptidase (W83) (10), putative DPP (TDC60) (37), and peptidase S9 A/B/C family catalytic domain protein (JCV1 SC001) (38). In the MEROPS peptidase database, PGN_1349 is classified into Clan SC, family S9, subfamily C of the peptidase S09.A77, for which the dipeptidylpeptidase family member 6 (DPF-6) from Caenorhabditis elegans (UniProt number P34422) is a representative. An orthologue search of PGN_1349 produced a long list of S9 family peptidase members (supplemental Table S1). This family comprises at least 142 genera of organisms, in which most orthologues are distributed in both Gram-negative and -positive bacteria, such as the phyla Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Cyanobacteria, and Firmicutes, but are also found in archaea (the phyla Euryarchaeota and Crenarhaeota), including Aeropyrum pernix, and eukaryotes (the phylum Nematoda), including C. elegans. The average amino acid length of the 477 DPF-6 members is 652 ± 62 (mean ± S.D.).

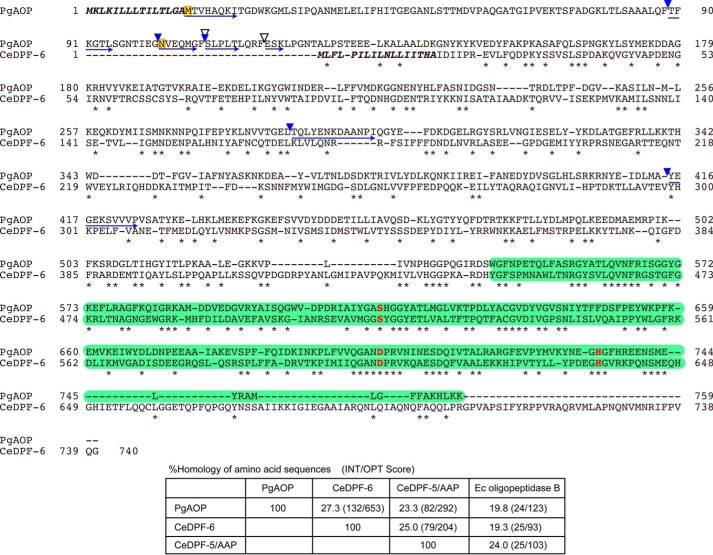

DPF-6 from C. elegans is composed of 740 amino acids (39) and postulated to have serine-type peptidase activity, whereas no actual activity in any family members has yet been reported. Alignment of the amino acid sequences indicates that the Ser-Asp-His catalytic triad and their adjacent sequences are highly conserved (Fig. 2). The peptidase S9 family motif is predicted to be present in the C-terminal half region in both PGN_1349 and DPF-6 by the Pfam database (40). The N-terminal part corresponding to Met16–Lys142 of PGN_1349 is absent in C. elegans DPF-6. Importantly, this sequence identity between PGN_1349 and C. elegans DPF-6 (27.3%, INT/OPT score = 132/653) is even higher than that with C. elegans DPF-5/AAP (23.3%, 82/292), which releases acylaminoacyl amino acids, or E. coli oligopeptidase B (19.8%, 24/123), which releases acyloligopeptides from the N terminus of peptides (Fig. 2, bottom). These findings strongly suggest that the enzymatic activities of DPF-6 family members are represented by that of P. gingivalis PGN_1349 and enzymatically distinct from DPF-5/AAP and oligopeptidase B.

FIGURE 2.

Comparison of amino acid sequences between PGN_1349 and C. elegans DPF-6. The amino acid sequence of PGN_1349 (PgAOP) was compared with that of C. elegans DPF-6 (CeDPF-6). Identical amino acids are indicated by asterisks. Potential sets of 3 amino acids (Ser615, Asp702, and His734) forming the essential triad of serine peptidases are indicated by red boldface letters. Putative signal sequences are shown in boldface italic type, and peptidase S9 family domains (residues 544–759 on PgAOP and 445–662 on CeDPF-6) are shown by green boxes. The starting amino acids (Met16 and Asn102) of recombinant proteins expressed in this study (see Fig. 5) are boxed in yellow. N-terminal sequences and the autoproteolytic cleavage sites producing 75-kDa species in the purified sample and 75- and 52-kDa species appearing after incubation at 37 °C for 6 days (Fig. 5) are indicated by blue arrows and arrowheads, respectively. Chymotryptic cleavage sites are indicated by open arrowheads. Bottom, percent homology of amino acid sequences among PgAOP, CeDPF-6, CeDPF-5/AAP, and E. coli (Ec) oligopeptidase B were determined using Genetyx software.

PGN_1349 Is a Novel Exopeptidase, Designated AOP

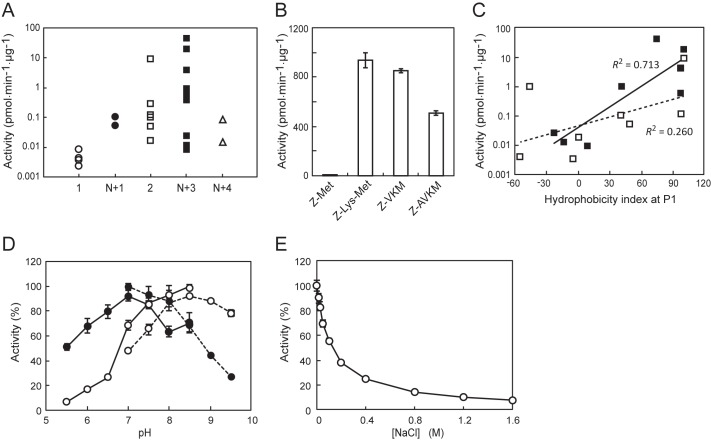

The peptidase activity of PGN_1349 is rearranged based on the residue numbers of 26 MCA substrates. It showed predominant release of tripeptides with N-terminal blockage. Other substrates, such as acylaminoacyl-, dipeptidyl-, and N-terminally blocked tetrapeptidyl-MCA, were slowly hydrolyzed, whereas aminoacyl-MCA was scarcely hydrolyzed (Fig. 3A). To more precisely evaluate the substrate length preference, we prepared a set of substrates with altered lengths (i.e. Z-Met-, Z-Lys-Met-, Z-VKM-, and Z-AVKM-MCA) and then determined the activities (Fig. 3B). PGN_1349 most potently hydrolyzed Z-Lys-Met-MCA, followed by Z-VKM-MCA. The hydrolysis of Z-AVKM-MCA was lower as compared with the former, and Z-Met-MCA was scarcely hydrolyzed. Taken together, we concluded that PGN_1349 is neither a DPP nor AAP, although it has acyl-oligopeptide-releasing activity. In order to more precisely evaluate the influence of N-terminal blockage on its enzymatic activity, the hydrolysis of four pairs of substrates, with the N-terminal either blocked or unblocked, was examined. As shown in Table 2, PGN_1349 consistently hydrolyzed the acylated substrates more efficiently than the substrates without N-terminal modification. Hence, we designated PGN_1349 as AOP.

FIGURE 3.

Properties of PGN_1349 (AOP). A, peptidase activities of AOP with MCA substrates were arranged according to the numbers of amino acids and N-terminal states. 1, aminoacyl-MCA (Ala-, Leu-, Met-, and Phe-MCA); N+1, N-terminal-modified aminoacyl-MCA (Ac-Ala- and Ac-Met-MCA); 2, dipeptidyl-MCA (Met-Leu-, Gly-Pro-, Gly-Phe-, Lys-Ala-, Ser-Tyr-, Gly-Gly-, Leu-Asp-, and Thr-Ser-MCA); N+3, N-terminal-modified tripeptidyl-MCA (Z-VKM-, Z-LLL-, glutalyl-AAF-, Suc-AAA-, Suc-IIW-, N-methoxysuccinyl-AAP-, Z-MEK-, Boc-FSR-, and Z-LLE-MCA); N+4, N-terminal-modified tetrapeptidyl-MCA (Suc-LLVY- and Z-LRGG-MCA). B, the activity of PGN_1349 was determined with Z-Met-, Z-Lys-Met-, Z-VKM-, and Z-AVKM-MCA. C, activities of dipeptidyl-MCA (open square, broken line, 2 in A) and N-terminally modified tripeptidyl-MCA (closed square, solid line, N+3) were replotted against the hydrophobicity index of the P1 residues. Data for Gly-Pro-MCA and N-methoxysuccinyl-MCA were omitted from this plot because of the peculiarity of the imino acid, Pro. D, the activity of recombinant AOP was determined with Met-Leu-MCA (open circle) and Z-VKM-MCA (closed circle) in 50 mm sodium phosphate (pH 5.5–8.5) or 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.0–9.5). The highest activities in phosphate buffer (pH 8.5) for Met-Leu-MCA (48.6 ± 0.9 pmol/min/μg) and in Tris-HCl (pH 7.0) for Z-VKM-MCA (367.9 ± 8.0 pmol/min/μg) were used as 100%. E, the activity of PGN_1349 for Z-VKM-MCA was determined at 0–1.6 m NaCl in 50 mm Tris-HCl buffer, pH 8.0. Values are shown as the mean ± S.D. (error bars) (n = 3).

TABLE 2.

Influence of N-terminal modification on peptidase activity of AOP

| MCA peptide | Activity | Increase by acylation |

|---|---|---|

| pmol min−1 μg−1 | -fold | |

| Ala | 0.04 ± 0.01 | |

| Ac-Ala | 0.40 ± 0.01 | 9.2 |

| Met | 0.01 ± 0.01 | |

| Ac-Met | 0.24 ± 0.02 | 21.5 |

| Lys-Met | 0.05 ± 0.16 | |

| Z-Lys-Met | 362.17 ± 1.13 | 7705.7 |

| AAF | 2.54 ± 0.13 | |

| Glutalyl-AAF | 34.58 ± 0.13 | 13.6 |

The P1 position amino acid preference of AOP was further examined using synthetic dipeptidyl-MCA or N-terminally modified tripeptidyl-MCA with different P1 amino acids. When the activities for these substrates were plotted against P1 amino acid residual hydrophobicity indexes (41), a close positive relationship with P1 position hydrophobicity was demonstrated with both the di- and tripeptidyl-MCA substrates (Fig. 3C). These results clearly indicate that AOP prefers hydrophobic residues at the P1 position.

The pH profile of AOP revealed an optimum pH of 8.5 for Met-Leu-MCA and 7.0 for Z-VKM-MCA. The activity was gradually decreased as the concentration of NaCl increased. Therefore, to achieve direct comparison with various substrates, the activity was simply measured in 50 mm sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.5, containing 5 mm EDTA in the absence of NaCl in the following experiments. We also tested the effects of reducing reagents (i.e. dithiothreitol, reduced glutathione, and oxidized glutathione) because it has been reported that they modulate the peptidase activity of oligopeptidase B (42). However, none (up to 1.6 mm) affected the peptidase activity of AOP (data not shown), again indicating characteristics distinct from oligopeptidase B.

The enzymatic parameters of AOP for the three substrates indicate that the kcat value was maximal for Z-Lys-Met-MCA (1155 ± 77 s−1), whereas Km was smallest for Z-VKM-MCA (4.9 ± 1.0 μm) and kcat/Km was maximal for Z-VKM-MCA (123.3 ± 17.0 μm−1 s−1) (Table 3). When the values were compared with those of P. gingivalis DPPs for their best dipeptidyl-MCA substrates, the kcat/Km values of AOP (58–123 μm−1 s−1) were shown to be comparable with those of DPP4, DPP5, DPP7, and DPP11 (11–548 μm−1 s−1), suggesting that AOP and the DPPs are able to function under similar substrate concentrations in the bacterium.

TABLE 3.

Enzymatic parameters of P. gingivalis exopeptidases

| Peptidase | MCA peptide | kcat | Km | kcat/Km | Source/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| s−1 | μm | μm−1 s−1 | |||

| AOP | Z-Lys-Met- | 1155 ± 77 | 17.8 ± 2.0 | 65.0 ± 3.7 | This study |

| Z-VKM- | 592 ± 40 | 4.9 ± 1.0 | 123.3 ± 17.3 | This study | |

| Z-AVKM- | 399 ± 13 | 6.9 ± 0.6 | 57.5 ± 3.7 | This study | |

| DPP4 | Gly-Pro- | 6917 ± 1253 | 100.9 ± 20.1 | 66.8 ± 2.0 | This study |

| DPP5 | Lys-Ala- | 1948 ± 165 | 185 ± 21 | 10.5 | Ref. 24 |

| DPP7 | Met-Leu- | 394 ± 79 | 39.6 ± 16.0 | 10.6 ± 2.5 | Ref. 25 |

| DPP11 | Leu-Asp- | 10,707 ± 140 | 19.5 ± 0.4 | 547.4 ± 6.3 | This study |

| Leu-Glu- | 13,587 ± 577 | 80.9 ± 5.7 | 167.7 ± 5.3 | This study |

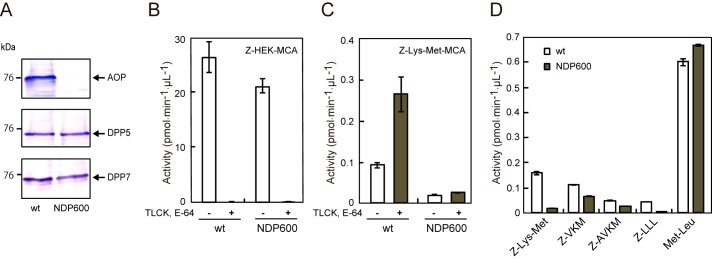

Peptidase Activities in aop Gene-disrupted Strain

An aop-disrupted strain, NDP600, was constructed, and the absence of AOP in the strain was confirmed by immunoblotting (Fig. 4A). Cell-associated peptidase activity of NDP600 was determined in the presence of 50 μm Nα-p-tosyl-l-lysine chloromethyl ketone (TLCK) and 3 μm E-64, under which the activity of Kgp toward Z-HEK-MCA was completely abolished in both the wild-type and NDP600 strains (Fig. 4B), whereas the addition of these gingipain inhibitors markedly enhanced Z-Lys-Met-MCA hydrolysis in the wild type. In contrast, this activity was greatly reduced in NDP600 both with and without the inhibitors (Fig. 4C). These results clearly demonstrated that AOP is the main peptidase responsible for this hydrolysis. Similarly, the hydrolysis of Z-LLL-MCA was significantly reduced in NDP600 (Fig. 4D). However, hydrolyses of Z-VKM- and Z-AVKM-MCA were modestly reduced in NDP600, presumably because of incomplete protection of the substrates from Kgp. On the other hand, that of Met-Leu-MCA was not affected by disruption of the aop gene, because this substrate was predominantly hydrolyzed by DPP5 (24) and DPP7 (25), which are active in NDP600. Taken together, these results suggest that AOP is primarily responsible for the release of di- and tripeptides with P1 hydrophobic residues from N-terminally blocked oligopeptides in P. gingivalis.

FIGURE 4.

Effect of gene disruption of AOP. A, cell suspensions (10 μl) from ATCC 33277 (WT) and an AOP-knock-out strain (NDP600) were subjected to immunoblotting analysis with anti-AOP, DPP5, and DPP7 antibodies. Z-HEK-MCA-hydrolyzing (B) and Z-Lys-Met-MCA-hydrolyzing activities (C) were determined with cell suspensions of WT and KDP600 in the absence or presence of 60 μm TLCK and 3 μm E-64. D, peptidase activities were determined using WT and NDP600 in the presence of TLCK and E-64. Error bars, S.D.

Active Serine and Endopeptidase Activity

Recombinant AOP was mainly purified as an 85-kDa species with the N-terminal sequence of ala−2-ile−1-Met16-Thr-Val-His-Ala-Gln-Lys-Ile23 (ala−2-ile−1 was derived from the vector sequence) due to release of the initial met−3 (Figs. 1 and 2). In addition, a minor 75-kDa species with the N-terminal sequences of Thr89-Phe-Lys-Gly-Thr-Leu94 and Asn102-Val-Glu-Gln-Met-Gly107 was occasionally obtained, indicating cleavage at the Phe88-Thr89 and Gly101-Asn102 bonds, respectively (Figs. 2 and 5A). These results suggested that the N-terminal region at around the 100th residue is protease-sensitive. Similarly, 75- and 70-kDa species were produced by limited proteolysis with chymotrypsin at the Phe108-Ser109 and Phe117-Glu118 bonds, respectively (data not shown).

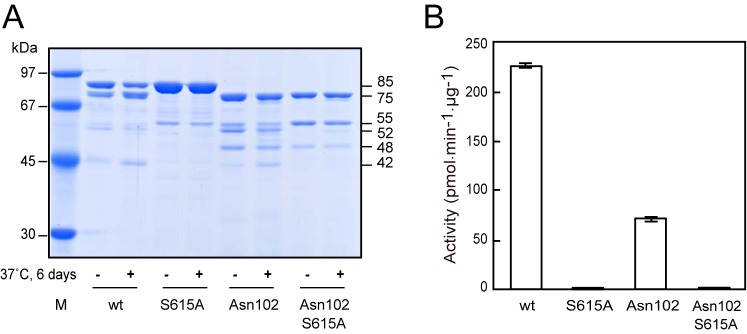

FIGURE 5.

Effects of N-terminal truncation and substitution of Ser615 in AOP. A, recombinant AOP and its derivatives (10 μg) were heated in 100 μl of SDS-sample buffer just after purification (−) or incubated at 37 °C for 6 days (+). Then aliquots (1 μg) were subjected to SDS-PAGE. Lane M, molecular weight markers. Apparent molecular masses of the major products are indicated on the right. B, activities of recombinant AOP and its derivatives were determined with Z-Lys-Met-MCA (mean ± S.D. (error bars), n = 3).

We compared the peptidase activities of several forms of AOP, in which either the N-terminal 101 residues were truncated (Asn102 form), the potentially essential Ser at position 615 was substituted by Ala (S615A form), or both. The S615A substitution completely abolished the activity (Fig. 5B). These results indicate that Ser615 is essential, as previously proposed (36). The N-terminally truncated Asn102 form maintained one-third of the activity, suggesting that the N-terminal 101 residues are not essential, although they have effects on peptidase activity.

Interestingly, 75-, 52-, and 42-kDa species emerged in enzymatically active forms and were increased by incubation at 37 °C for 6 days (Fig. 5A), suggesting an autoproteolytic activity of AOP. In accord with the P1 hydrophobic preference of AOP activity, the cleavage sites of the 52- and 42-kDa species were Leu290-Tyr291 and Ala414-Tyr415, respectively. Endopeptidase activity of AOP was further confirmed because it degraded 14.3-kDa α-lactalbumin into 7.5- and 8.5-kDa species at the Gln62-Asn63 and Gln58-Ala59 bonds, respectively (data not shown) and was estimated to be less than one-one hundredth of that of α-chymotrypsin when assessed with α-lactalbumin as a substrate.

Oligomerization and Subcellular Localization

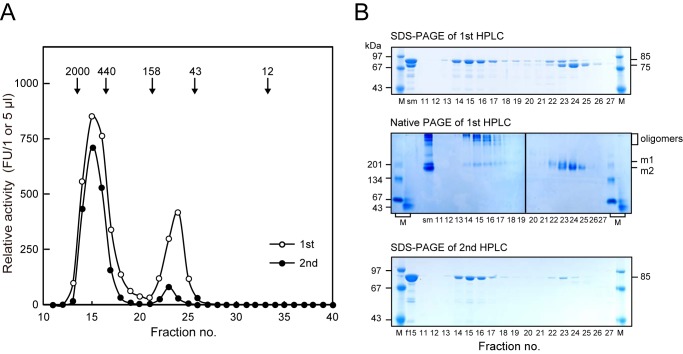

We also examined the molecular structure of AOP in an aqueous solution using size exclusion HPLC (Fig. 6). The hydrolyzing activity of purified AOP was split into a major peak larger than 440 kDa and a minor 85-kDa peak. Fractions 14–17 of the first HPLC consisted solely of the 85-kDa species, as shown by SDS-PAGE, whereas the second peak at fractions 22–25 consisted of both the 85- and 75-kDa entities. Native PAGE confirmed that the 85-kDa species in the first peak formed oligomers and that the 85- and 75-kDa species in the second peak were monomers (m1 and m2, respectively). Furthermore, the second HPLC of the large peak sample (fraction 15 of the first HPLC) consisting of the 85-kDa species reproduced the two-peak profile. These findings clearly indicated an equilibrium of oligomeric and monomeric forms of the 85-kDa AOP in solution and comparable specific activities of these two forms. Because the 75-kDa species starting at Thr89 or Asn102 was a monomer, the N-terminal region (Met16–Glu101) appears to be indispensable for AOP oligomerization.

FIGURE 6.

Molecular status of recombinant AOP. A, AOP (10 mg/0.3 ml) and fraction 15 of the first HPLC (0.3 ml) were subjected to size exclusion HPLC (first and second, respectively) with a Superdex200 10/300 column, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Relative activities (first, FU/μl and, second, FU/5 μl) were determined with Z-VKM-MCA. Molecular markers run in parallel were as follows: blue dextran 2000 (2000 kDa), ferritin (440 kDa), aldolase (158 kDa), ovalbumin (43 kDa), and cytochrome c (12 kDa). B, aliquots (2.5 μl for SDS-PAGE and 10 μl for native PAGE) of each fraction of the first HPLC were separated on polyacrylamide gels under denaturing (SDS-PAGE) and non-denaturing (native PAGE) conditions. sm, starting material (2 μg with SDS-PAGE, 16 μg with native PAGE). Positions of oligomers and monomers (m1 and m2) are indicated. Fraction 15 of the first HPLC (f15) and each fraction (5 μl) of the second HPLC were separated on SDS-polyacrylamide gels. Lanes M, molecular weight markers.

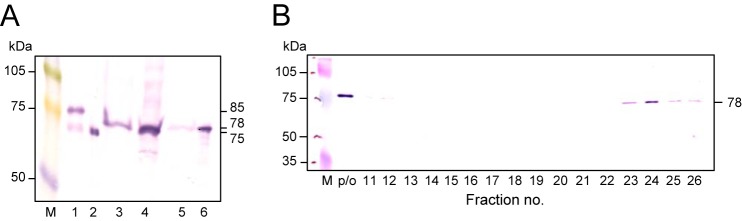

In P. gingivalis KDP136 cells, the apparent molecular mass of native AOP was found to be 78 kDa (Fig. 7), suggesting the loss of some region as compared with 85- and 75-kDa AOP, although the N terminus of the 78-kDa form could not be determined. AOP at 78 kDa was predominantly detected in the periplasm/outer membrane and cytosol fractions. When the periplasmic/outer membrane fraction was subjected to size exclusion HPLC, 78-kDa AOP was detected as a monomer at fractions 23–26. Because the cytosolic preparation contained a considerable amount of periplasmic components, P. gingivalis AOP appears to be primarily distributed in the periplasm and present mainly as a monomer in cells. In accord with these findings, a previous proteome analysis also found that PG_1004, an orthologue of PGN_1349 in P. gingivalis W83, was mainly recovered in cytosol/periplasm and periplasm fractions (43).

FIGURE 7.

Molecular status of endogenous AOP. A, recombinant AOP (50 ng) and subcellular fractions of KDP136 (2 μg of protein) were separated on SDS-polyacrylamide gels and subjected to immunoblotting. Lane M, full-length rainbow molecular weight marker; lane 1, recombinant WT AOP; lane 2, Asn102; lane 3, KDP136 whole cells; lane 4, cytosol; lane 5, inner membrane; lane 6, periplasm/outer membrane. B, the periplasm/outer membrane fraction of KDP136 (0.3 ml) was loaded onto an HPLC column, as described in the legend to Fig. 6. Aliquots (5 μl) of separated fractions were subjected to SDS-PAGE and then visualized by immunoblotting with the anti-AOP antibody. p/o, periplasm/outer membrane fraction (5 μl).

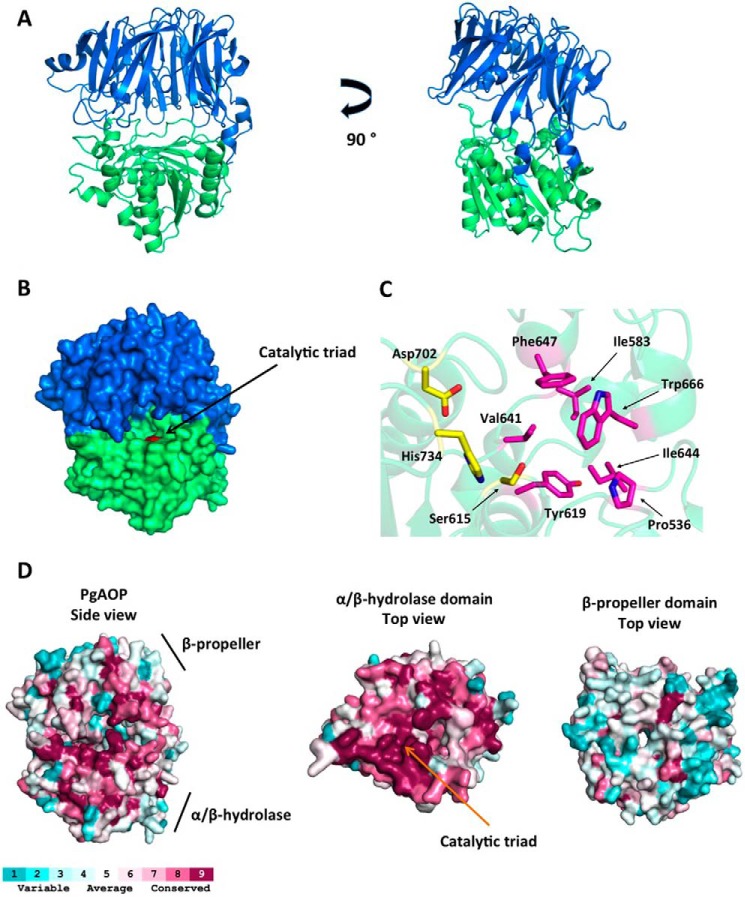

Modeling of Three-dimensional Structure

Psipred and GenThreader results indicate that AOP possesses three domains: Met16–Ala126, which has no similar homologue with known three-dimensional structure, and Leu127–Met495 and Ala496–Phe736, which form β-propeller and α/β-hydrolase domains, respectively. The three-dimensional model comprises residues Ala138–Lys759 and bears the domain organization of S9 family members, as indicated by GenThread. The α/β-hydrolase domain hosts the catalytic triad (Ser615, Asp702, and His734) and is responsible for the enzymatic activity, whereas the β-propeller provides enzyme specificity (Fig. 8, A and B).

FIGURE 8.

Three-dimensional homology model of AOP. A, schematic representation of AOP three-dimensional structure; the β-propeller domain (Ala138–Met495) is shown in blue, and the α/β-hydrolase domain (Ala496–Lys759) is shown in green. B, surface representation of AOP with the catalytic triad region (red). C, stick representation of catalytic triad (yellow) and the residues forming the S1 subsite (magenta). D, surface representation of AOP colored in terms of evolutionary conservation of its amino acids. Psi-BLAST, Cobalt, and Consurf were used to calculate the conservation scores. Left, side view of AOP. Middle, top view of the α/β-hydrolase domain; the β-propeller was removed for better visualization. Right, top view of the β-propeller domain. The color code ranges from blue (non-conserved) to red (conserved). The figure was prepared using the program PyMOL (Schroedinger, LLC, New York).

In agreement with the hydrophobic P1 preference, the S1 site is formed by the hydrophobic residues: Pro536, Ile583, Tyr619, Val641, Ile644, Phe647, and Trp666 (Fig. 8C). Differently from DPPs, which have an N-anchor region determining the protein specificity (44, 45), our model indicates a more open active site without any steric impediment for its oligopeptidase feature. The autoproteolytic site (Gly101-Asn102) associated with the production of the 75-kDa truncated AOP is localized in the N-terminal domain, which suggests that this region is very likely exposed to the solvent, reasonably explaining the site accessibility by another AOP molecule.

To estimate the evolutionary conservation of amino acid positions in AOP, we performed a Psi-BLAST (33) search with the AOP sequence, followed by multialignment in Cobalt (46), and mapped their conservation onto the AOP structure, using the server Consurf (47). This analysis revealed that the α/β-hydrolase domain is more conserved than the β-propeller domain (Fig. 8D), in agreement with the observation that the β-propeller domain is responsible for enzyme specificity. Therefore, the β-propeller domain is expected to present more variation among the proteins than the α/β-hydrolase domain, which provides the catalytic activity shared by all members. Furthermore, because the oligomer interface region lies in the N terminus, we hypothesize that AOP might display a novel oligomer formation process. In this way, determining the three-dimensional structure of AOP by an experimental method (e.g. x-ray crystallography) could shed light upon its mechanism of action.

Discussion

In the present study, we identified a novel exopeptidase encoded by the gene PGN_1349 in the P. gingivalis strain ATCC 33277. This enzyme, designated AOP, was found to possess active Ser615, to most preferentially degrade peptide bonds between Yaa2-Xaa3 and Yaa3-Xaa4 (where Yaa is a hydrophobic amino acid) of oligopeptides with N-terminally blocked oligopeptides, and to exist mainly in the periplasmic space as a monomer. Furthermore, AOP showed a tendency to oligomerization at the N-terminal 100-amino acid region; thus, it may bind to other molecules via interactions in this region. Our three-dimensional modeling results also indicated a conserved structure of S9 peptidases coinciding with the hydrophobic P1 preference of AOP.

Peptidase activities of three of seven members categorized as P. gingivalis S9 family proteins have been identified in previous studies (i.e. DPP4, DPP5, and PTP-A) (14, 15, 24, 27), whereas the present study identified the fourth, AOP. Whether the remaining three (i.e. PGN_1542 (annotated as esterase), PGN_1694 (Ala-DPP), and PGN_1878 (hypothetical protein)) possess hydrolyzing activity remains unknown (24) (this study); however, we confirmed here that they could not release N-acylated amino acids from MCA substrates available in our laboratory. Therefore, to the best of our knowledge, AOP is a unique exopeptidase that hydrolyzes nutritional N-terminally blocked peptides in P. gingivalis. The activity of AOP may provide substantial benefits for efficient utilization of amino acids by the bacterium. Notably, when considering its habitat in the subgingival space, the bacterium frequently utilizes serum proteins contained in gingival crevicular fluid, some of which are N-terminally blocked by acyltransferase or glutamyl cyclase by processing into their secretary forms (48).

Our comparison of amino acid sequences supported the kinship of AOP with C. elegans DPP-6 (S9.A77). On the other hand, sequence homologies were rather lower among AOP, C. elegans DPF-5/AAP, and E. coli oligopeptidase B, and their peptidase characteristics are obviously distant. Although both AOP and DPF-5/AAP exhibit a hydrophobic P1 preference, a typical feature of mammalian (S09.004) and Aeropyrum-type (S09.070) AAP is removal of an N-acylated hydrophobic amino acid from oligopeptides with various N-terminal acyl groups (49, 50). Because of this activity, AAP is also termed an acylamino acid-releasing enzyme. In contrast, AOP was shown to scarcely release acylamino acids but preferably released di- and tripeptides (Fig. 1). Furthermore, the P1 hydrophobic preference of AOP is clearly distinct from oligopeptidase B, which targets basic amino acid residues, such as Arg (51). On the other hand, both share common features in that these exopeptidases poorly exhibit aminopeptidase activity and possess elevated activities against N-acylated substrates (52) (this study). Therefore, DPF-6 family members, including P. gingivalis AOP, should be considered as the third exopeptidase group in the S9 family responsible for N-terminally blocked peptidyl substrates. Although AOP possessed a weak endopeptidase activity, this activity was also reported on AAP (53).

In supplemental Table S1, Bacteroides peptidases, such as Bacteroides fragilis (BF9343_3151, 23.4% amino acid identity), Bacteroides vulgatus (BVU_4083, 21.6%), and Bacteroides thetiotaomicron (BT_1838, 23.8%) are listed as homologues of P. gingivalis AOP (PGN_1349). Among them, BT_1838 and BVU_4083 are annotated as Ala-DPP in the S9 family, of which the enzymatic activity remains unknown (24). The amino acid identities of P. gingivalis Ala-DPP (PGN_1694) with BF_9343_3151 from B. fragilis, BVU_4083, and BT_1838 are 39.1, 39.4, and 40.2%, respectively, which are substantially higher than those with P. gingivalis AOP. In fact, we cloned BF_9343_3151 and expressed its recombinant form in E. coli as an 80-kDa protein. It did not show any peptidase activity (data not shown), as P. gingivalis Ala-DPP did not (24). Therefore, we conclude that not all proteins of supplemental Table S1 are AOP, especially those with lower similarities. The final annotation of AOP should be carefully done in future studies. In addition, a study on peptidase activity of Ala-DPP is now under way in our laboratory.

Subcellular fractionation experiments demonstrated that P. gingivalis AOP is localized in the periplasmic space as a monomer. It has been reported that S9 family members are present as various molecular forms (50), because oligopeptidase B and prolyl oligopeptidase were found to exist as monomers (42), and DPP4 (54) and PTP-A (17) were found to exist as dimers, whereas the dimeric structure of human DPP4 is indispensable for peptidase activity (54). In addition, mammalian and A. pernix AAPs are present as a tetramer (55) and dimer (56), respectively. P. gingivalis DPP5 also forms a homodimer (24). In this study, we found that recombinant AOP exists in equilibrium between a large oligomer and monomer. It is interesting to note that two forms of AOP demonstrated peptidase activity, and the specific activities of both seem to be equal. Furthermore, our findings indicated that the N-terminal region is indispensable for oligomerization, although the biological meaning of AOP oligomerization is obscure at present. This region might be related to heteromeric interactions with periplasmic components, such as other peptidases and peptidoglycan.

Genome and biochemical analyses of P. gingivalis demonstrated the presence of two oligopeptide transporters (9, 10) and a Ser/Thr transporter (57). Previous studies reported that di- and tripeptides are predominantly incorporated into cells (18, 19); thus, they appear to be major cargoes for the oligopeptide transporters, and the contribution of the Ser/Thr transporter toward nutritional amino acid incorporation may be limited. Regarding this point, there is a critical difference between P. gingivalis and E. coli, a well studied Gram-negative rod that does not possess DPPs and predominantly incorporates single amino acids (58, 59). It is possible that DPPs/PTP-A and oligopeptide transporters co-evolved, which may explain, at least in part, why novel exopeptidases (i.e. DPP11 (27), DPP5 (24), and AOP (this study)) have recently been discovered in P. gingivalis.

Based on our findings, we describe the metabolism of extracellular oligopeptides in P. gingivalis as follows. P. gingivalis produces oligopeptides from extracellular polypeptides by potent cysteine peptidases, Kgp and Rgp, located in the outer membrane and extracellular space. Subsequently, oligopeptides are converted in periplasmic space into di- and tripeptides by DPPs and PTP-A, respectively, with DPP5 and DPP7 functioning with oligopeptides with hydrophobic residues at the second position from the N terminus. Additionally, the P2 position hydrophobic residue enhances the activities of DPP7 (26). Those with Pro at the second and third positions are cleaved by DPP4 and PTP-A, respectively. Oligopeptides with the penultimate acidic residues Asp and Glu are metabolized by DPP11, whereas those with the basic residues Lys and Arg are metabolized by gingipains. Moreover, N-terminally blocked oligopeptides are segregated by AOP into acylated di- and tripeptides and N-terminally unblocked oligopeptides, which are then processed by DPPs and PTP-A. These di- and tripeptides are promptly incorporated via oligopeptide transporters in the inner membrane. Efficient utilization of extracellular proteins as carbon and energy sources is made possible by coordination of a series of exopeptidases and nutritional oligopeptide transporters in P. gingivalis, which may have inevitably evolved to choose and adapt its anaerobic subgingival habitat, where carbohydrates are consumed mainly by oral streptococci.

Author Contributions

T. K. N. and Y. O.-N. designed and performed the experiments. Y. S. and S. K. performed amino acid sequencing. G. A. B. performed three-dimensional modeling. T. K. N. and Y. O.-N. wrote the first draft. All authors contributed to and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

This study was supported by Grants-in-aid for Scientific Research 15K11047 (to T. K. N.) and 25462894 (to Y. O.-N.) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science and a grant from the Joint Research Promotion Project of Nagasaki University Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences in 2014 (to Y. O.-N.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

This article contains supplemental Table S1.

- Rgp

- Arg-gingipain

- Kgp

- Lys-gingipain

- DPP

- dipeptidyl-peptidase

- PTP-A

- prolyl tripeptidylpeptidase A

- AOP

- acylpeptidyl oligopeptidase

- AAP

- acylaminoacyl peptidase

- MCA

- 4-methycoumaryl-7-amide

- Z-

- benzyloxycarbonyl-

- Suc-

- succinyl-

- Boc-

- t-butyloxycarbonyl- ((2S)-2-amino-3-(benzyloxycarbonyl) propionyl-)

- TLCK

- Nα-p-tosyl-l-lysine chloromethyl ketone

- DPF

- dipeptidylpeptidase family member.

References

- 1. Griffen A. L., Becker M. R., Lyons S. R., Moeschberger M. L., and Leys E. J. (1998) Prevalence of Porphyromonas gingivalis and periodontal health status. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36, 3239–3242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Holt S. C., and Ebersole J. L. (2005) Porphyromonas gingivalis, Treponema denticola, and Tannerella forsythia: the “red complex”, a prototype polybacterial pathogenic consortium in periodontitis. Periodontology 2000 38, 72–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. White D., and Mayrand D. (1981) Association of oral Bacteroides with gingivitis and adult periodontitis. J. Periodontal Res. 16, 259–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Moore W. E. C., Holdeman L. V., Smibert R. M., Good I. J., Burmeister J. A., Palcanis K. G., and Ranney R. R. (1982) Bacteriology of experimental gingivitis in young adult humans. Infect. Immun. 38, 651–667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Loesche W. J., Syed S. A., Schmidt E., and Morrison E. C. (1985) Bacterial profiles of subgingival plaques in periodontitis. J. Periodontol. 56, 447–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Iwai T., Inoue Y., Umeda M., Huang Y., Kurihara N., Koike M., and Ishikawa I. (2005) Oral bacteria in the occluded arteries of patients with Buerger disease. J. Vasc. Surg. 42, 107–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kshirsagar A. V., Offenbacher S., Moss K. L., Barros S. P., and Beck J. D. (2007) Antibodies to periodontal organisms are associated with decreased kidney function. The dental atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Blood Purif. 25, 125–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Detert J., Pischon N., Burmester G. R., and Buttgereit F. (2010) The association between rheumatoid arthritis and periodontal disease. Arthritis Res. Ther. 12, 218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Meuric V., Rouillon A., Chandad F., and Bonnaure-Mallet M. (2010) Putative respiratory chain of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Future Microbiol. 5, 717–734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nelson K. E., Fleischmann R. D., DeBoy R. T., Paulsen I. T., Fouts D. E., Eisen J. A., Daugherty S. C., Dodson R. J., Durkin A. S., Gwinn M., Haft D. H., Kolonay J. F., Nelson W. C., Mason T., Tallon L., Gray J., Granger D., Tettelin H., Dong H., Galvin J. L., Duncan M. J., Dewhirst F. E., and Fraser C. M. (2003) Complete genome sequence of the oral pathogenic bacterium Porphyromonas gingivalis strain W83. J. Bacteriol. 185, 5591–5601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shah H. N., Gharbia S. E., Kowlessur D., Wilkie E., and Brocklehurst K. (1990) Isolation and characterization of gingivain, a cysteine proteinase from Porphyromonas gingivalis strain W83. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 18, 578–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chen Z., Potempa J., Polanowski A., Wikstrom M., and Travis J. (1992) Molecular cloning and structural characterization of the Arg-gingipain proteinase of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Biosynthesis as a proteinase-adhesin polyprotein. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 18896–18901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Abiko Y., Hayakawa M., Murai S., and Takiguchi H. (1985) Glycylprolyl dipeptidylaminopeptidase from Bacteroides gingivalis. J. Dent. Res. 64, 106–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Banbula A., Bugno M., Goldstein J., Yen J., Nelson D., Travis J., and Potempa J. (2000) Emerging family of proline-specific peptidases of Porphyromonas gingivalis: purification and characterization of serine dipeptidyl peptidase, a structural and functional homologue of mammalian prolyl dipeptidyl peptidase IV. Infect. Immun. 68, 1176–1182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Banbula A., Yen J., Oleksy A., Mak P., Bugno M., Travis J., and Potempa J. (2001) Porphyromonas gingivalis DPP-7 represents a novel type of dipeptidylpeptidase. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 6299–6305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Banbula A., Mak P., Bugno M., Silberring J., Dubin A., Nelson D., Travis J., and Potempa J. (1999) Prolyl tripeptidyl peptidase from Porphyromonas gingivalis: a novel enzyme with possible pathological implications for the development of periodontitis. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 9246–9252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ito K., Nakajima Y., Xu Y., Yamada N., Onohara Y., Ito T., Matsubara F., Kabashima T., Nakayama K., and Yoshimoto T. (2006) Crystal structure and mechanism of tripeptidyl activity of prolyl tripeptidyl aminopeptidase from. Porphyromonas gingivalis. J. Mol. Biol. 362, 228–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Takahashi N., Sato T., and Yamada T. (2000) Metabolic pathways for cytotoxic end product formation from glutamate- and aspartate-containing peptides by. Porphyromonas gingivalis. J. Bacteriol. 182, 4704–4710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Takahashi N., and Sato T. (2001) Preferential utilization of dipeptides by Porphyromonas gingivalis. J. Dent. Res. 80, 1425–1429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tang-Larsen J., Claesson R., Edlund M. B., and Carlsson J. (1995) Competition for peptides and amino acids among periodontal bacteria. J. Periodontal Res. 30, 390–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Singer R. E., and Buckner B. A. (1981) Butyrate and propionate: important components of toxic dental plaque extracts. Infect. Immun. 32, 458–463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ho Y.-C., and Chang Y.-C. (2007) Effects of a bacterial lipid byproduct on human pulp fibroblasts in vitro. J. Endod. 33, 437–441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kurita-Ochiai T., Seto S., Suzuki N., Yamamoto M., Otsuka K., Abe K., Ochiai K. (2008) Butyric acid induces apoptosis in inflamed fibroblasts. J. Dent. Res. 87, 51–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ohara-Nemoto Y., Rouf S. M., Naito M., Yanase A., Tetsuo F., Ono T., Kobayakawa T., Shimoyama Y., Kimura S., Nakayama K., Saiki K., Konishi K., and Nemoto T. K. (2014) Identification and characterization of prokaryotic dipeptidyl-peptidase 5 from Porphyromonas gingivalis. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 5436–5448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rouf S. M., Ohara-Nemoto Y., Hoshino T., Fujiwara T., Ono T., and Nemoto T. K. (2013) Discrimination based on Gly and Arg/Ser at position 673 between dipeptidyl-peptidase (DPP) 7 and DPP11, widely distributed DPPs in pathogenic and environmental Gram-negative bacteria. Biochimie 95, 824–832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rouf S. M., Ohara-Nemoto Y., Ono T., Shimoyama Y., Kimura S., and Nemoto T. K. (2013) Phenylalanine 664 of dipeptidyl peptidase (DPP) 7 and phenylalanine 671 of DPP11 mediate preference for P2-position hydrophobic residues of a substrate. FEBS Open Bio. 3, 177–183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ohara-Nemoto Y., Shimoyama Y., Kimura S., Kon A., Haraga H., Ono T., and Nemoto T. K. (2011) Asp- and Glu-specific novel dipeptidyl peptidase 11 of Porphyromonas gingivalis ensures utilization of proteinaceous energy sources. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 38115–38127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shi Y., Ratnayake D. B., Okamoto K., Abe N., Yamamoto K., and Nakayama K. (1999) Genetic analyses of proteolysis, hemoglobin binding, and hemagglutination of Porphyromonas gingivalis: construction of mutants with a combination of rgpA, rgpB, kgp, and hagA. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 17955–17960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Naito M., Hirakawa H., Yamashita A., Ohara N., Shoji M., Yukitake H., Nakayama K., Toh H., Yoshimura F., Kuhara S., Hattori M., Hayashi T., and Nakayama K. (2008) Determination of the genome sequence of Porphyromonas gingivalis strain ATCC 33277 and genomic comparison with strain W83 revealed extensive genome rearrangements in P. gingivalis. DNA Res. 15, 215–225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nguyen K. A., Travis J., and Potempa J. (2007) Does the importance of the C-terminal residues in the maturation of RgpB from Porphyromonas gingivalis reveal a novel mechanism for protein export in a subgroup of Gram-negative bacteria? J. Bacteriol. 189, 833–843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Buchan D. W. A., Minneci F., Nugent T. C. O., Bryson K., and Jones D. T. (2013) Scalable web services for the PSIPRED Protein Analysis Workbench. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, W349–W357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lobley A., Sadowski M. I., and Jones D. T. (2009) pGenTHREADER and pDomTHREADER: new methods for improved protein fold recognition and superfamily discrimination. Bioinformatics 25, 1761–1767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Altschul S. F., Madden T. L., Schäffer A. A., Zhang J., Zhang Z., Miller W., and Lipman D. J. (1997) Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 3389–3402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kelley L. A., Mezulis S., Yates C. M., Wass M. N., and Sternberg M. J. (2015) The Phyre2 web portal for protein modeling, prediction and analysis. Nat. Protoc. 10, 845–858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Menyhárd D. K., Kiss-Szemán A., Tichy-Rács É., Hornung B., Rádi K., Szeltner Z., Domokos K., Szamosi I., Náray-Szabó G., Polgár L., and Harmat V. (2013) A self-compartmentalizing hexamer serine protease from Pyrococcus horikoshii: substrate selection achieved through multimerization. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 17884–17894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rawlings N. D., Waller M., Barrett A.-J., and Bateman A. (2014) MEROPS: the database of proteolytic enzymes, their substrates and inhibitors. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D503–D509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Watanabe T., Maruyama F., Nozawa T., Aoki A., Okano S., Shibata Y., Oshima K., Kurokawa K., Hattori M., Nakagawa I., and Abiko Y. (2011) Complete genome sequence of the bacterium Porphyromonas gingivalis TDC60, which causes periodontal disease. J. Bacteriol. 193, 4259–4260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. McLean J. S., Lombardo M. J., Ziegler M. G., Novotny M., Yee-Greenbaum J., Badger J. H., Tesler G., Nurk S., Lesin V., Brami D., Hall A. P., Edlund A., Allen L. Z., Durkin S., Reed S., Torriani F., Nealson K. H., Pevzner P. A., Friedman R., Venter J. C., and Lasken R. S. (2013) Genome of the pathogen Porphyromonas gingivalis recovered from a biofilm in a hospital sink using a high-throughput single-cell genomics platform. Genome Res. 23, 867–877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wilson R., Ainscough R., Anderson K., Baynes C., Berks M., Bonfield J., Burton J., Connell M., Copsey T., and Cooper J. (1994) 2.2 Mb of contiguous nucleotide sequence from chromosome III of C. elegans. Nature 368, 32–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Finn R. D., Bateman A., Clements J., Coggill P., Eberhardt R. Y., Eddy S. R., Heger A., Hetherington K., Holm L., Mistry J., Sonnhammer E. L., Tate J., and Punta M. (2014) Pfam: the protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D222–D230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Monera O. D., Sereda T. J., Zhou N. E., Kay C. M., and Hodges R. S. (1995) Relationship of side chain hydrophobicity and α-helical propensity on the stability of the single-stranded amphipathic α-helix. J. Pept. Sci. 1, 319–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Usuki H., Uesugi Y., Iwabuchi M., and Hatanaka T. (2009) Activation of oligopeptidase B from Streptomyces griseus by thiol-reacting reagents is independent of the single reactive cysteine residue. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1794, 1673–1683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Veith P. D., Chen Y. Y., Gorasia D. G., Chen D., Glew M. D., O'Brien-Simpson N. M., Cecil J. D., Holden J. A., and Reynolds E. C. (2014) Porphyromonas gingivalis outer membrane vesicles exclusively contain outer membrane and periplasmic proteins and carry a cargo enriched with virulence factors. J. Proteome Res. 13, 2420–2432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Oefner C., D'Arcy A., Mac Sweeney A., Pierau S., Gardiner R., and Dale G. E. (2003) High-resolution structure of human apo dipeptidyl peptidase IV/CD26 and its complex with 1-[({2-[(5-iodopyridin-2-yl)amino]-ethyl}amino)-acetyl]-2-cyano-(S)-pyrrolidine. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 59, 1206–1212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bezerra G. A., Dobrovetsky E., Dong A., Seitova A., Crombett L., Shewchuk L. M., Hassell A. M., Sweitzer S. M., Sweitzer T. D., McDevitt P. J., Johanson K. O., Kennedy-Wilson K. M., Cossar D., Bochkarev A., Gruber K., and Dhe-Paganon S. (2012) Structures of human DPP7 reveal the molecular basis of specific inhibition and the architectural diversity of proline-specific peptidases. PLoS One 7, e43019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Papadopoulos J. S., and Agarwala R. (2007) COBALT: constraint-based alignment tool for multiple protein sequences. Bioinformatics 23, 1073–1079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Armon A., Graur D., and Ben-Tal N. (2001) ConSurf: an algorithmic tool for the identification of functional regions in proteins by surface mapping of phylogenetic information. J. Mol. Biol. 307, 447–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sykes P. A., Watson S. J., Temple J. S., and Bateman R. C. Jr. (1999) Evidence for tissue-specific forms of glutaminyl cyclase. FEBS Lett. 455, 159–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Abraham C. R., and Nagle M. W. (2012) Acylaminoacyl-peptidase. in Handbook of Proteolytic Enzymes, 3rd Ed (Rawlings N. D., Salvesen G. S., eds)pp. 3401–3403, Elsevier, Amsterdam [Google Scholar]

- 50. Polgár L. (2002) The prolyl oligopeptidase family. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 59, 349–362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kanatani A., Masuda T., Shimoda T., Misoka F., Lin X. S., Yoshimoto T., and Tsuru D. (1991) Protease II from Escherichia coli: sequencing and expression of the enzyme gene and characterization of the expressed enzyme. J. Biochem. 110, 315–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Morty R. E., Authié E., Troeberg L., Lonsdale-Eccles J. D., and Coetzer T. H. (1999) Purification and characterization of a trypsin-like serine oligopeptidase from Trypanosoma congolense. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 102, 145–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kiss A. L., Hornung B., Rádi K., Gengeliczki Z., Sztáray B., Juhász T., Szeltner Z., Harmat V., and Polgár L. (2007) The acylaminoacyl peptidase from Aeropyrum pernix K1 thought to be an exopeptidase displays endopeptidase activity. J. Mol. Biol. 368, 509–520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Chien C. H., Huang L. H., Chou C. Y., Chen Y. S., Han Y. S., Chang G. G., Liang P. H., and Chen X. (2004) One site mutation disrupts dimer formation in human DPP-IV proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 52338–52345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Gade W., and Brown J. L. (1978) Purification and partial characterization of α-N-acylpeptide hydrolase from bovine liver. J. Biol. Chem. 253, 5012–5018 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Bartlam M., Wang G., Yang H., Gao R., Zhao X., Xie G., Cao S., Feng Y., and Rao Z. (2004) Crystal structure of an acylpeptide hydrolase/esterase from Aeropyrum pernix K1. Structure 12, 1481–1488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Dashper S. G., Brownfield L., Slakeski N., Zilm P. S., Rogers A. H., and Reynolds E. C. (2001) Sodium ion-driven serine/threonine transport in Porphyromonas gingivalis. J. Bacteriol. 183, 4142–4148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Piperno J. R., and Oxender D. L. (1968) Amino acid transporter systems in Escherichia coli K12. J. Biol. Chem. 243, 5914–5920 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Schellenberg G. D., and Furlong C. E. (1977) Resolution of the multiplivcity of the glutamate and aspartate transport systems of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 252, 9055–9064 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.