Abstract

Cellular signaling through protein tyrosine phosphorylation is well established in mammalian cells. Although lacking the classic tyrosine kinases present in humans, plants have a tyrosine phospho-proteome that rivals human cells. Here we report a novel plant tyrosine phosphatase from Arabidopsis thaliana (AtRLPH2) that, surprisingly, has the sequence hallmarks of a phospho-serine/threonine phosphatase belonging to the PPP family. Rhizobiales/Rhodobacterales/Rhodospirillaceae-like phosphatases (RLPHs) are conserved in plants and several other eukaryotes, but not in animals. We demonstrate that AtRLPH2 is localized to the plant cell cytosol, is resistant to the classic serine/threonine phosphatase inhibitors okadaic acid and microcystin, but is inhibited by the tyrosine phosphatase inhibitor orthovanadate and is particularly sensitive to inhibition by the adenylates, ATP and ADP. AtRLPH2 displays remarkable selectivity toward tyrosine-phosphorylated peptides versus serine/threonine phospho-peptides and readily dephosphorylates a classic tyrosine phosphatase protein substrate, suggesting that in vivo it is a tyrosine phosphatase. To date, only one other tyrosine phosphatase is known in plants; thus AtRLPH2 represents one of the missing pieces in the plant tyrosine phosphatase repertoire and supports the concept of protein tyrosine phosphorylation as a key regulatory event in plants.

Keywords: Arabidopsis thaliana, Phosphoprotein phosphatase, protein phosphatase, protein phosphorylation, protein serine/threonine phosphatase (PSP), tyrosine-protein phosphatase (tyrosine phosphatase), serine/threonine phosphatase

Introduction

Reversible protein phosphorylation, mediated by protein kinases and phosphatases, is a regulatory mechanism key to the functioning of all cell types. With an estimated minimum of 75% of all human proteins controlled by this mechanism (1), connecting the biochemical characteristics of protein kinases and phosphatases to their cellular function is of central importance. Reversible protein phosphorylation can occur on a number of residues, but largely occurs in both plants and animals on serine, threonine, and tyrosine residues at approximate percentages of 86, 12, and 2, respectively (2–6).

Protein kinases exist as one large superfamily with over 1050 members encoded in the genome of the model organism Arabidopsis thaliana (6). Conversely, A. thaliana maintains only 150 protein phosphatases, which are categorized into four distinct families conserved across eukaryotes. These include the phospho-protein phosphatases (PPPs),4 phospho-protein metallo-phosphatases (PPMs), phospho-tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs), and the Asp-based catalysis phosphatases (7). Unlike protein kinases, which employ a single catalytic mechanism, each of the four protein phosphatase families employs differing catalytic mechanisms (7). The PPP, PPM, and Asp-based protein phosphatases coordinate metal ions in their active sites to assist in catalysis, and each has been shown to specifically target phosphorylated serine (pSer) and threonine (pThr) residues on protein substrates (7). The PPM catalytic domains have N- and C-terminal extensions that confer substrate specificity and regulation, whereas the PPP family enzymes all have additional subunits that define function (6). The PTP family protein phosphatases operate independently of metal ion co-factors (7, 8), and alternatively employ a cysteine from the conserved CX5R motif to catalyze the removal of phosphate from substrates. The PTP family was defined by their ability to dephosphorylate phospho-tyrosine (pTyr) residues. In humans, this group is now referred to as the classic PTPs and is described as specifically dephosphorylating only pTyr on proteins. Other PTP family members exist including a large subset of proteins called the dual specificity phosphatases (8–10). These phosphatases maintain a variety of catalytic site structures capable of dephosphorylating pTyr, pSer, and pThr residues in addition to other molecules such as phospho-inositides, glycogen/starch, and mRNA (8, 10). A. thaliana genome analysis has identified many homologues of the human dual specificity phosphatases, but only a single classic PTP family phosphatase (11, 12), whereas humans maintain 38 of the classic tyrosine-specific enzymes (9). Despite the presence of only a single pTyr-specific classic PTP family phosphatase in plants (AtPTP1), phospho-proteomic studies have consistently found levels of protein tyrosine phosphorylation in A. thaliana and Oryza sativa (2, 13) that parallel in abundance to humans.

Recently, two new groups of PPP family protein phosphatases were identified in plants that possess all the defining PPP enzyme motifs and domains (14–16), but overall appear to be more related to bacterial protein phosphatases. The first group, the Shewanella-like phosphatases (SLP1 and SLP2), form two highly conserved and phylogenetically distinct sub-groups across all plants (15, 16). The second group of bacteria-like protein phosphatases is the Rhizobiales/Rhodobacterales/Rhodospirillaceae-like phosphatases (RLPHs), which were named due to their phylogenetic relatedness to phosphatases encoded by these bacterial groups (14, 16). It is the RLPHs that are the focus of this study. We present a comprehensive analysis of A. thaliana RLPH2 (AtRLPH2), a novel phospho-tyrosine-specific PPP family protein phosphatase.

Experimental Procedures

Protein concentration was determined by Bradford reagent using BSA as a standard.

Plant and Cell Culture Growth

A. thaliana wild type seeds were surface-sterilized for 4 h, placed in either magenta boxes containing liquid Murashige and Skoog medium or 0.6% agar plates containing 0.5× Murashige and Skoog medium, and stratified in the dark at 4 °C for 2 days. Magenta boxes were placed under constant light for 10 days with one medium change. Seedlings from plates were transferred to soil and grown in 12-h light/12-h dark conditions for 45 days. Roots from magenta boxes and each part of the plant (rosette, stem, flower, and silique) were harvested, frozen with liquid N2, and kept at −80 °C. A. thaliana cell culture was sub-cultured every 10 days in a 1:10 ratio, harvested, and stored as in Ref. 17.

AtRLPH2 T-DNA Insertion Lines

T-DNA insertion mutant lines for atrlph2-1 (RATM-13-2130-1_G) and atrlph2-2 (RATM-13-3204-1_G) were obtained from RIKEN and are in a Nössen background. Homozygosity of the insertion and absence of AtRLPH2 expression was screened by PCR (data not shown) and Western blotting, respectively (see Fig. 1).

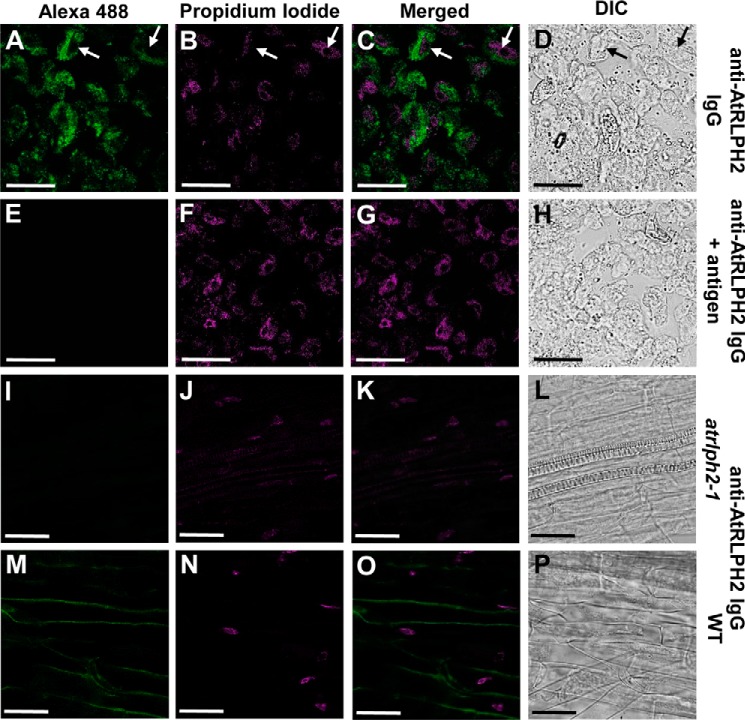

FIGURE 1.

AtRLPH2 is a widely expressed cytosolic enzyme. A, affinity-purified anti-AtRLPH2 IgG (2 μg/ml) detected down to 0.25 ng of purified AtRLPH2-V5-H6 by Western blotting (WB). B, AtRLPH2 antibody (2 μg/ml) was used to probe either a WT or two separate AtRLPH2 T-DNA insertion line crude extracts (atrlph2-1, atrlph2-2). Prior to Western blotting, the membrane was Ponceau S (PS)-stained for equal loading (lower panel). AtRLPH2 is detected as an immunoreactive band at 36 kDa. C, extracts from various A. thaliana plant tissues probed with anti-AtRLPH2 IgG demonstrate broad tissue expression of AtRLPH2. D, crude lysate, isolated nuclei, and cytosolic fractions from A. thaliana rosettes (left panels) and cell culture (right panels) were Western blotted (WB) for AtRLPH2. Known cytosolic marker UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase (UGPase) and nuclear marker histone H3 were used to verify the subcellular localization of AtRLPH2 and purity of each fraction. All mass markers are shown in kDa.

Cloning of AtRLPH2 and AtSLP1

At3g09970 (AtRLPH2) and At1g07010 (AtSLP1) clones were obtained from The Arabidopsis Information Resource. Each was propagated by PCR (AtRLPH2-fwd ATGGCGCAAAAACCACGAACGGTG; AtRLPH2-rev ACTAGACAAATTATCGGTGTCACGGAT; AtSLP1-fwd ATGGCTTCCCTTTACCTCAATTCC; AtSLP1-rev ATAGTAATCTGCAACCTGAAGTTC) with primers that additionally contained forward and reverse Gateway homologous recombination adaptor sites (Invitrogen). PCR products were inserted into pDONR221 and further subcloned into expression vector pYL436 to create C-terminal tandem affinity purification (cTAP) fusion constructs (17). pET-DEST42 was used to create the AtRLPH2 C-terminal V5-HIS6 (AtRLPH2-V5-H6) fusion construct. AtSLP1-H6 construct was created previously (15).

Protein Expression and Purification

AtRLPH2-V5-H6 was expressed in BL21 (DE3) CodonPlus-RIL Escherichia coli at 22 °C, with 0.1 mm isopropyl-1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside for 18 h, and purified in two steps using Ni-NTA followed by Mono-Q chromatography as described in Ref. 15. The unbound Mono-Q fraction contained >95% pure AtRLPH2-V5-H6 (data not shown) and was confirmed to be AtRLPH2 by mass spectrometry. AtSLP1-H6 was purified using Ni-NTA as described previously (15).

The GST-Fer construct, obtained from Dr. Nicholas Tonks (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory), was transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3) CodonPlus-RIL (18), expression was induced with 0.4 mm isopropyl-1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside at 37 °C for 2 h, and the construct was purified on glutathione-Sepharose 4B (GE Healthcare).

Tandem Affinity Purification (TAP) of AtSLP1 and AtRLPH2

AtSLP1 and AtRLPH2 TAP-tagged constructs were transformed into Agrobacterium GV3101 and used to transfect A. thaliana via the floral dip method (19). AtSLP1- and AtRLPH2-TAP-expressing A. thaliana plants were grown in soil under a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle. AtSLP1- and AtRLPH2-TAP proteins were isolated in parallel, each from 20 g of rosette tissue, as described previously (17), and was employed in enzyme assays immediately after the final Ni-NTA purification step, where the matrix was washed but not eluted.

Anti-AtRLPH2 Antibodies

Pure bacterial expressed AtRLPH2-V5-H6 was used as an antigen to generate polyclonal antibodies in a rabbit (20). Anti-AtRLPH2 IgG was affinity-purified from crude immune serum by a membrane method as described previously (21).

Immunoprecipitation

Either anti-AtRLPH2 IgG or rabbit pre-immune serum (PIS) IgG (40 μg) was incubated with protein A-Sepharose 4B (Life Technologies) and covalently coupled to the bead as in Ref. 22. Dark-grown A. thaliana cell culture protein extract (50–70 mg) (23) was mixed with the antibody-coupled beads end-over-end for 4 h at 4 °C. Beads were washed 5 times with 1 ml of 50 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl and 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20.

Immunoblotting

Protein was extracted from different plant tissues as described in Ref. 23, and 5 μg were separated by 14% SDS-PAGE, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, blocked, and probed with 2 μg/ml anti-AtRLPH2 antibody, followed by secondary antibody diluted 1:5000 and developed with ECL (PerkinElmer).

Nuclei were purified from A. thaliana rosette tissue as outlined in the method outlined in Ref. 39. Proteins from nuclei isolation were separated on 10% SDS-PAGE, the blotted membrane was cut in three sections, and each was probed with either 2 μg/ml anti-AtRLPH2 antibody or 1:2500 anti-histone H3 antibody (Abcam, ab1791) for nuclear detection or 1:2000 anti-UGPase antibody (Agrisera, AS05086) for cytoplasmic detection.

Anti-phospho-tyrosine antibody validation was performed using peptides phosphorylated on tyrosine, threonine, or serine ((BRCA1) QSPKVpTFECEQK, (RVSF) KRRVpSFADK, and (SAPK4) RHADAEMTGpYVVTR (200 μg each)) coupled with 2.5% (v/v) glutaraldehyde to 1 mg of BSA in the presence of 25 mm NaF and 1 mm Na3VO4 in PBS. Coupled peptides, as well as recombinant autophosphorylated GST-Fer, were spotted onto a membrane and probed with anti-phospho-tyrosine antibody, PY99 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc7020) diluted 1:100 in 1% (w/v) BSA, 25 mm Tris pH 7.5, 0.5 m NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20, 25 mm NaF, and 1 mm Na3VO4 for 16 h at 4 °C followed by secondary antibody and development with ECL Prime (GE Healthcare).

Enzymatic Analysis

AtRLPH2 activity was measured either by the small molecule phosphatase substrate para-nitrophenylphosphate (24) (pNPP; Sigma) or by measuring phosphatase-catalyzed phosphate release from metabolites or phospho-peptide substrates using malachite green reagent (24, 25). Standard pNPP assay conditions included pre-incubation of 150 ng of AtRLPH2-V5-H6 with small molecules in 1× dilution buffer consisting of 100 mm HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl (totaling a volume of 20 μl) for 10 min at 30 °C. Each assay was then supplemented with 130 μl of buffer containing 5 mm pNPP followed by an additional 10-min incubation at 30 °C.

Malachite green (Sigma-Aldrich) assays were performed using 1 μg of recombinant phosphatase protein incubated for 1 h at 30 °C in 160 μl of buffer containing each substrate with control assays lacking protein phosphatase. To determine kinetic parameters, assays were performed for 30 min using the rSAPK3 peptide (see Table 1) with pTyr, pSer, or pThr at the phospho-position. Km and kcat were determined using the Michaelis-Menten and Lineweaver-Burk plots.

TABLE 1.

Malachite green dephosphorylation assay examining AtRLPH2 activity towards phosphorylated peptides

Assays were performed in triplicate using 1 mm phospho-peptide and 1 μg of bacterially expressed and purified AtRLPH2-V5-H6. Phosphorylated amino acids are shown in bold. All peptides are derived from human sequences except rSAPK3, which is rat SAPK3. Values are followed by ± S.E. (n = 3).

| Peptide origin | Peptide sequence | nmol of Pi min−1 mg−1 |

|---|---|---|

| RRP1B | SSKKVpTFGLN | 0.997 ± 0.009 |

| BRCA1 | QSPKVpTFECEQK | 1.92 ± 0.03 |

| Ki67 | KRRRVpSFGGH | 1.479 ± 0.004 |

| B56 | KLQGIDpSQGVNQ | 1.82 ± 0.03 |

| HIPK4 | VKEPpYIQSR | 17.3 ± 0.4 |

| HIPK | VCSTpYLQSR | 18.3 ± 1.4 |

| hSAPK4s | EMTGpYVVTR | 18.8 ± 0.5 |

| PINK1 | RAHLESRSpYQEAQLPAR | 32.4 ± 0.6 |

| ICK | KPPYTDpYVSTR | 37.6 ± 0.9 |

| DAPP1 | PRKVEEPSIpYESVRVH | 49.8 ± 1.2 |

| hSAPK4 | RHADAEMTGpYVVTR | 99.7 ± 1.6 |

| rSAPK3 | RQADSEMTGpYVVTR | 103.0 ± 1.6 |

Assays performed using TAP-purified AtSLP1- and AtRLPH2-cTAP employed 65 μl of protein phosphatase-bound Ni-NTA isolated from 20 g of rosette tissue. Each aliquot of coupled Ni-NTA matrix was resuspended in 235 μl of buffer containing phosphorylated peptide and was incubated for 1 h at 30 °C. Ni-NTA matrix was pelleted, and 160 μl of reaction mix were removed and quenched with malachite green solution.

Beads with immunoprecipitated endogenous AtRLPH2 (and control beads) from one-half of an IP experiment were resuspended in 160 μl of 1× dilution buffer containing the phosphorylated peptide. Controls consisting of a blank without enzyme and a PIS IgG IP were performed in parallel. Each assay was incubated for 1.25 h at 30 °C. Beads were pelleted, and supernatant was quenched with malachite green solution. IP assays employed phospho-peptides derived from the proteins: DAPP1 (PRKVEEPSIpYESVRVH), SPAK (CTRNKVRKpTFVGTP), and TSC2, (QLHRSVpSWADSAK), with phospho-residues as indicated.

For GST-Fer dephosphorylation assays, immunoprecipitated endogenous AtRLPH2 beads (and PIS control) were resuspended in 1× dilution buffer containing 0.5 μg of phospho-GST-Fer and incubated at 30 °C for up to 24 min. Every 3 min, one tube was boiled with 5× SDS mixture. GST-Fer tyrosine phosphorylation state was tested by immunoblotting with anti-phospho-tyrosine antibody as described above. For loading control, the membrane was stripped with 2 m MgCl2 and 0.1% acetic acid for 10 min at room temperature and then probed with anti-GST antibody (Immunology Consultants Laboratory, RGST-45A-Z). This experiment was performed in triplicate, and the representative blot is shown. Bands were quantified with ImageJ.

AtRLPH2 Subcellular Localization by Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence imaging was performed as in Ref. 26 with the following changes. A. thaliana culture cells and seedlings were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde prior to aldehyde group reduction. Cell wall digestion did not include meicelase. The antibody incubations included 5 μg/ml anti-AtRLPH2 IgG or 5 μg/ml anti-AtRLPH2 IgG quenched with 100 μg/ml purified AtRLPH2-V5-H6. Nuclear staining was performed with 10 μg/ml propidium iodide supplemented with 10 μg/ml RNase for 12 min at 37 °C. Cells or seedlings were mounted on a microscopy slide with 50% (v/v) glycerol and visualized at room temperature on a confocal microscope (Leica TCS SP5) in oil at 40× and an aperture of 1.3, with the following excitation (Ex) and emission (Em) settings: propidium iodide (red), Ex/Em used was 543/603–674 nm; Alexa Fluor 488 (green), Ex/Em used was 488/503–536 nm.

Results

AtRLPH2 Is a Broadly Expressed Cytosolic Phosphatase

Previous bioinformatic analysis determined RLPH2 to be found widely across photosynthetic eukaryotes, where it was predicted to have a cytosolic localization (16). To confirm its subcellular localization and tissue expression, we generated and affinity-purified antibodies to recombinant AtRLPH2 (see “Experimental Procedures” and Fig. 1). This antibody could detect as little as 0.25 ng of tagged AtRLPH2 (Fig. 1A) and detected a protein in crude extracts at the predicted mass (∼36 kDa) of the endogenous AtRLPH2 (Fig. 1B). This band was confirmed to be AtRLPH2 by demonstrating its disappearance in two separate knock-out lines (Fig. 1B), neither of which displayed any obvious growth phenotype. Western blotting of A. thaliana tissues demonstrated AtRLPH2 protein expression in all tissues examined (Fig. 1C).

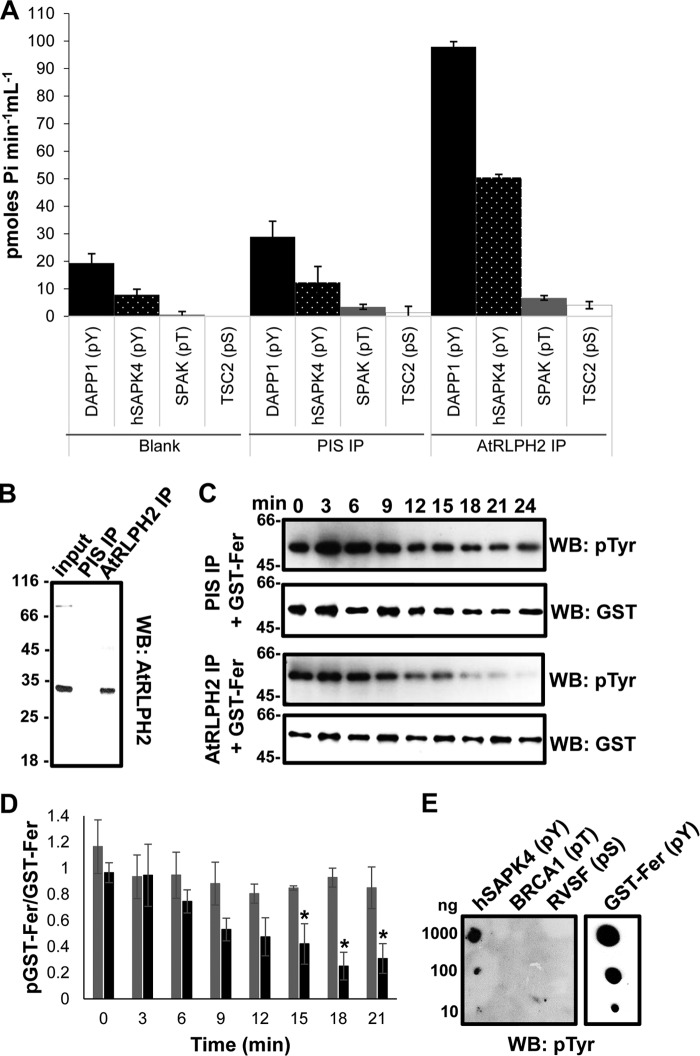

To explore AtRLPH2 subcellular localization, nuclear and cytosolic fractions were prepared from both rosettes and cell culture. Blotting each fraction with cytosolic and nuclear marker proteins (Fig. 1D) revealed a cytosolic localization for AtRLPH2. Consistent with cell fractionation and bioinformatics, immunolocalization imaging of cultured A. thaliana cells revealed that AtRLPH2 is cytosolic and excluded from the nucleus (Fig. 2, A–H). Identical results were found in A. thaliana roots (Fig. 2, M–P). No signal was observed when the knock-out line atrlph2-1 was used (Fig. 2, I–L), supporting the notion that the anti-AtRLPH2 signal observed in Fig. 2, A and M is derived solely from antibody binding AtRLPH2. The immunoreactive band of ∼50 kDa observed during Western blotting (Fig. 1B) is likely an epitope only exposed once proteins are denatured in SDS. Blotting with PIS IgG gave no signal for roots or cell culture (data not shown).

FIGURE 2.

Immunofluorescence imaging of AtRLPH2 in A. thaliana cell culture and roots. A–C, affinity-purified antibody was used to localize AtRLPH2 in cultured cells. A, fixed cells were probed with anti-AtRLPH2 IgG (5 μg/ml) and visualized with Alexa Fluor 488 (Alexa 488)-conjugated secondary antibody, whereas DNA was stained and visualized with propidium iodide (B), and the images were merged (C). White arrows indicate nuclei where AtRLPH2 is excluded. Controls with antigen-blocked anti-AtRLPH2 IgG are shown in panels E–G. In panels I–K, A. thaliana roots from the T-DNA insertion line atrlph2-1 were probed with anti-AtRLPH2 IgG and visualized with Alexa Fluor 488 (I), DNA was marked with propidium iodide (J), and the signals were merged (K). The same is shown for WT roots in panels M–O. Panels D, H, L, and P are the differential interference contrast (DIC)/Nomarski images of the left-hand panel of cells. Scale bar = 25 μm.

Enzymatic Characterization of AtRLPH2

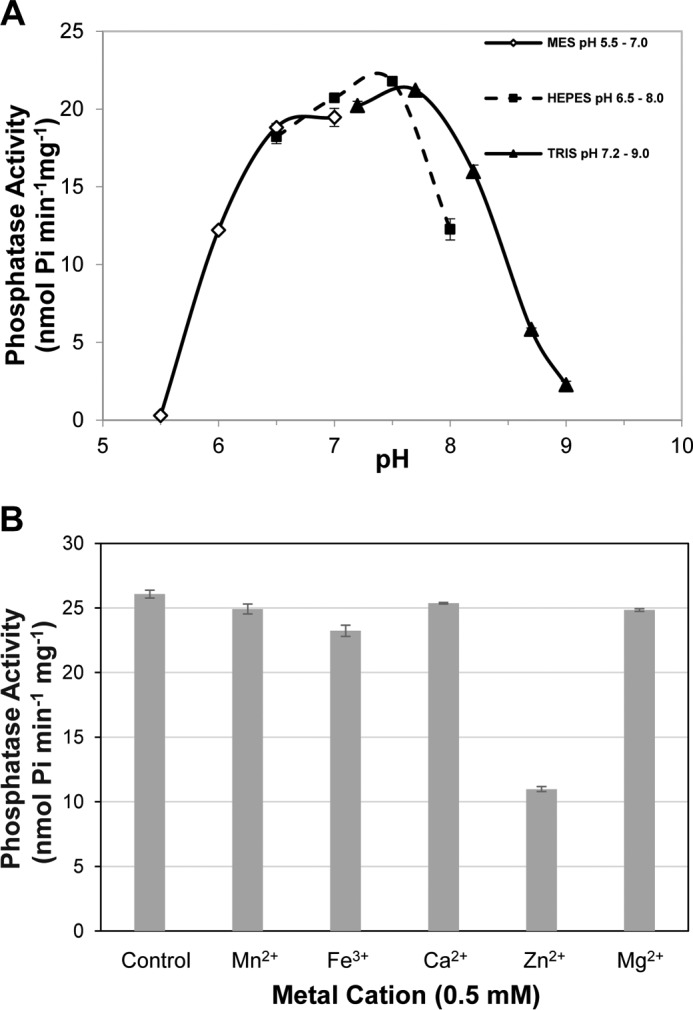

Poly-His-tagged AtRLPH2 (AtRHLPH2-V5-H6) was expressed and purified from E. coli. Size exclusion chromatography revealed a monomer of 49.1 kDa, despite a denatured SDS-PAGE mass of ∼40 kDa (data not shown). AtRLPH2 was found to have a pH optimum of 7.0–7.8 (Fig. 3A) with a specific activity of 20 nmol Pi min−1 mg−1 toward the artificial phosphatase substrate pNPP (Fig. 3A). Screening of known metal cation co-factors of various protein and non-protein phosphatases showed no stimulation of phosphatase activity, with highest activity observed in the control condition containing 5 mm EDTA (Fig. 3B). Interestingly, Zn2+ inhibited the phosphatase activity of AtRLPH2, just as Zn2+ is the most potent metal ion inhibitor of human classic tyrosine phosphatases (27).

FIGURE 3.

AtRLPH2 pH activity profile and metal cation dependence. A, E. coli-expressed and -purified AtRLPH2-V5-H6 pH activity profile was assessed from pH 5.5 to 9. Activity assays were conducted in the absence of metal cations. B, AtRLPH2-V5-H6 assayed in the presence of 0.5 mm metal cations (Mn2+, Fe3+, Ca2+, Zn2+, and Mg2+) or absence of metal cations (control containing 5 mm EDTA). All assays were performed using 150 ng of bacterially expressed and purified AtRLPH2 and the phosphatase substrate pNPP. Error bars represent S.E. (n = 3).

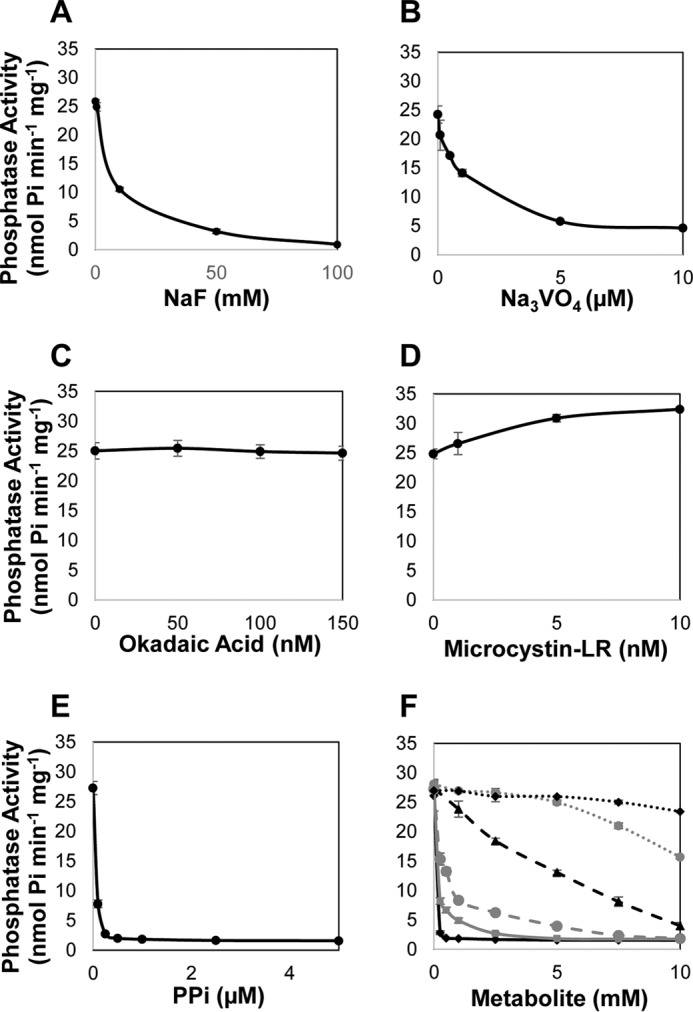

Several phosphate-containing compounds and classic protein phosphatase inhibitors were evaluated for their inhibitory effect on AtRLPH2 (Fig. 4). Phosphate analogs NaF and Na3VO4 are PPP and PTP family protein phosphatase-specific small molecule inhibitors, respectively (27). Both NaF and Na3VO4 substantially reduced AtRLPH2 activity with IC50 values of 8.9 mm and 2.1 μm, respectively (Fig. 4, A and B). Additionally, the naturally occurring PPP family protein phosphatase-specific small molecule inhibitors okadaic acid and microcystin-LR were also examined for their inhibitory effect on AtRLPH2 (Fig. 4, C and D). Concentrations that would completely inhibit the PPP family member PP2A failed to have any inhibitory effect on AtRLPH2. AtRLPH2 also exhibited nanomolar PPi sensitivity (IC50 350 nm), in addition to micromolar to millimolar sensitivity to ADP (IC50 356 μm), Pi (IC50 1.1 mm), and AMP (IC50 5.2 mm), as well as remarkable sensitivity to ATP (IC50 2.2 μm) (Fig. 4, E and F). Glucose 6-phosphate and glycerol 3-phosphate had no notable inhibitory effect on AtRLPH2 activity up to a 5 mm concentration (Fig. 4F).

FIGURE 4.

AtRLPH2 sensitivity to classic PPP and PTP phosphatase inhibitors. A–F, recombinant AtRLPH2 incubated with increasing amounts of NaF (A), Na3VO4 (B), okadaic acid (C), microcystin-LR (D), and PPi (E), and ATP (black diamonds), ADP (gray squares), AMP (black triangles), Pi (gray circles), glucose 6-phosphate (black diamonds; dashed black line), or glycerol 3-phosphate (gray circles; dashed gray line) (F) in conjunction with the phosphatase substrate pNPP. All assays were performed using 150 ng of bacterially expressed and purified AtRLPH2. Error bars represent S.E. (n = 3).

AtRLPH2 Is a Phospho-tyrosine-specific PPP Family Protein Phosphatase

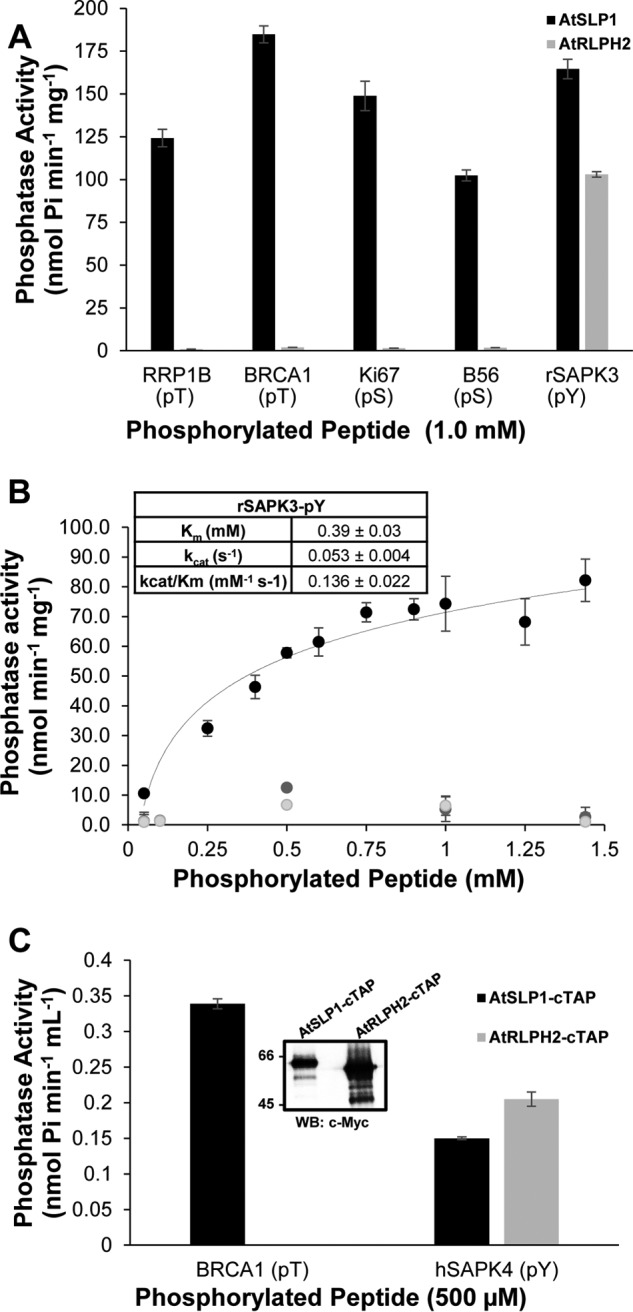

Utilizing Ser, Thr, and Tyr phospho-peptides to decipher the substrate preferences of PPP family members (PP1, PP2A, PP2B, PP2C) and classic PTPs has previously been employed successfully (28–32). Therefore, using a panel of phosphorylated peptides consisting of pSer, pThr, and pTyr, the substrate specificity of AtRLPH2 was evaluated (Table 1). AtRLPH2 exhibited low activity toward pSer- and pThr-only peptides, but displayed typically 50-fold greater activity against pTyr-containing peptides. No measurable activity was detected when employing the non-phospho-peptide substrates phospho-enolpyruvate, AMP, ADP, ATP, GTP, dATP, dihydroxyacetone phosphate, PPi, glucose-6-P, and glycerol-3-P. Among the A. thaliana PPP family enzymes, we recently characterized the other bacteria-like phosphatases, Shewanella-like protein phosphatases AtSLP1 and AtSLP2 (15). For comparison, bacterially expressed AtSLP1 was assayed in parallel with AtRLPH2 to assess its preference for pSer, pThr, and pTyr peptides (Fig. 5A). Unlike AtRLPH2, AtSLP1 exhibited a broad specificity profile for phospho-peptide substrates, effectively dephosphorylating pSer, pThr, and pTyr peptides. Next we performed assays to determine AtRLPH2 kinetic parameters toward a pSer, pThr, and pTyr peptide (Fig. 5B). To allow a direct comparison, we selected the rSAPK3 peptide and also synthesized the same peptide with pSer or pThr in place of the pTyr residue. Due to the extremely low activity with the pSer and pThr peptides, no reliable Km or kcat values could be determined. However, using the pTyr-containing rSAPK3 peptide, we determined a kcat value of 0.053 s−1 and a Km of ∼390 μm.

FIGURE 5.

Phospho-peptide substrate preferences of purified A. thaliana bacteria-like PPP family protein phosphatases. A. thaliana SLP1 (AtSLP1, black bars) and RLPH2 (AtRLPH2, gray bars) were expressed and purified as tagged fusion proteins in E. coli. A, 1 μg of each purified phosphatase was incubated with 1 mm designated phosphorylated peptide at 30 °C for 1 h to determine their phospho-substrate preference. The phospho-residue is indicated below the peptide name. pT, pThr; pS, pSer; pY, pTyr. B, bacterially expressed tagged AtRLPH2 kinetic constants were determined by performing assays with increasing amounts of rSAPK3 peptide (pTyr; black), or rSAPK3 peptide with a pSer (light gray) or pThr (dark gray) substituted for the pTyr. Only the pTyr peptide yielded adequate activity to calculate Km, kcat, and kcat/Km values, which are presented in the inset. C, constitutively expressed AtSLP1-cTAP (black bars) and AtRLPH2-cTAP (gray bars) were isolated from A. thaliana rosette leaf tissue as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Incubation of each TAP purified protein with either 500 μm BRCA1 (pThr) or 500 μm hSAPK4 (pTyr) phospho-peptides revealed each protein phosphatase substrate preference. The inset shows a Western blot (WB) of the Myc epitope of the TAP tag on each protein to demonstrate that equal amounts of phosphatase were used in each assay. Phosphatase activity was determined using a stop time malachite green assay. Error bars represent S.E. (n = 3).

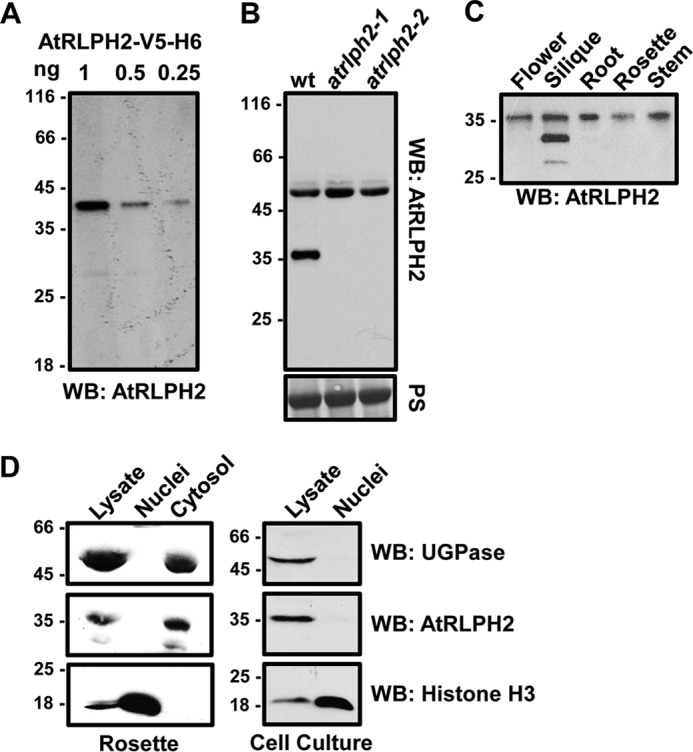

Next we employed TAP of overexpressed, in planta constructed AtSLP1 and AtRLPH2 to verify these phospho-peptide substrate preferences (Fig. 5C). Using equal amounts of enzyme, AtRLPH2-cTAP displayed little to no detectable activity toward a pThr-containing peptide, but still robustly dephosphorylated a pTyr peptide, whereas AtSLP1-cTAP still maintained measurable phosphatase activity toward the pTyr peptide, but with a marked preference for the pThr-containing peptide. To further support this observation, we next immunoprecipitated the endogenous AtRLPH2 from wild type plant cell culture for in vitro assays, and again the enzyme displayed a remarkable preference for pTyr peptides (Fig. 6A).

FIGURE 6.

Endogenous AtRLPH2 preferentially targets pTyr residues. A, affinity-purified anti-AtRLPH2 IgG, in parallel with PIS IgG and a peptide-only control (blank), was used to assay endogenous AtRLPH2 from a dark cell culture extract. Bead-bound AtRLPH2 was used to dephosphorylate two pTyr (pY) peptides (DAPP1, black bars; hSAPK4, white dotted black bars), a pThr (pT) peptide (SPAK3, gray bars), and a pSer (pS) peptide (TSC2, white bars) (see “Experimental Procedures” and Table 1 for peptide sequences). Error bars represent S.E. (n = 3). B, the clarified lysate (input) as well as PIS and anti-AtRLPH2 IP eluates were immunoblotted (WB) for AtRLPH2. Mass markers are shown in kDa. C, both the endogenous immunoprecipitated AtRLPH2 and the PIS control were used to dephosphorylate the autophosphorylated tyrosine kinase Fer. Aliquots of the assay were removed at the time points shown for SDS-PAGE and anti-phospho-tyrosine Western blotting (WB) analysis. Subsequently, blots were striped and probed with anti-GST IgG to visualize the quantity of GST-tagged Fer protein kinase on the membrane. A representative blot from three separate experiments is shown. In D, the Western blotting signal intensity for each time point shown in C was determined as outlined under “Experimental Procedures” and plotted as the ratio of phospho-GST-Fer to total GST-Fer. PIS IP is shown as black bars, and AtRLPH2 IP is shown as gray bars. Error bars depict ± S.E. (n = 3), and the asterisks depict a significance p ≤ 0.05 (two-tailed student's t test). E, phosphorylated peptides hSAPK4 (pTyr), BRCA1 (pThr), and RVSF (pSer) (defined under “Experimental Procedures”) or autophosphorylated GST-Fer were spotted to a membrane and probed with the anti-phospho-tyrosine IgG. In all panels, the antibody used for Western blotting (WB) is indicated.

The human tyrosine kinase Fer (Fps/Fes-related) autophosphorylates on tyrosine residues when expressed in bacteria. This makes it an excellent substrate for human classic PTPs (18). We purified the bacterially expressed auto-phosphorylated GST-Fer kinase, (Fig. 6E) and used it in an assay with immunoprecipitated AtRLPH2 (Fig. 6B). As shown in Fig. 6, C and D, AtRLPH2 readily dephosphorylated the pTyr-protein, again supporting the notion that in vivo, AtRLPH2 is a tyrosine phosphatase.

Discussion

In human cells, ∼2% of protein phosphorylation events occur on tyrosine. It is well established that this ∼2% is a fundamental component of cellular signaling (5). Despite an equivalent degree of tyrosine phosphorylation in humans and plants, genome analysis of plants has revealed a lack of dedicated tyrosine kinases. Select members of the large receptor-like protein kinase, calcium-dependent protein kinase (CDPKs), and MAPKK (MEK) families in A. thaliana have shown an ability to phosphorylate proteins on tyrosine, exhibiting dual specificity for the phosphorylation of Ser, Thr, and Tyr (33). Additionally, the glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) and calcium-dependent protein kinase-related enzymes (CRKs) autophosphorylate on tyrosine (34). There are two main subfamilies of protein phosphatases capable of dephosphorylating pTyr: the classic and dual specificity PTPs. The classic PTP subfamily enzymes are dedicated tyrosine phosphatases, whereas several dual specificity PTP subfamily enzymes dephosphorylate pTyr, but most target other specific phospho-substrates, including pSer and pThr (8). Plants encode for a single tyrosine phosphatase equivalent to the human enzymes (PTP1) (11), and it has the ability to dephosphorylate the activation loop pTyr of AtMPK4 (35). Plants also encode for many equivalents of the human dual specificity subfamily of PTPs (9, 12). As a whole, this body of evidence supports the idea that protein tyrosine phosphorylation is a key aspect of plant signaling, yet only a single tyrosine-specific protein phosphatase has been characterized in plants.

A number of plant protein phosphatases resemble bacterial phosphatases (14–16), which, based on sequence, clearly belong to the Ser/Thr-specific PPP family enzymes. In this study, we show that one of these enzymes, AtRLPH2, is cytosolic, completely resistant to the classic PPP family inhibitors okadaic acid and microcystin, but sensitive to the adenylates ADP and ATP at concentrations that are physiologically relevant. Although we have yet to uncover the substrates of AtRLPH2 in vivo, our results clearly indicate that AtRLPH2 is a protein-tyrosine phosphatase, and we predict that adenylates play a key role in controlling the action of the phosphatase on protein substrates. This suggests that AtRLPH2 phospho-targets are potentially linked to energy status and metabolism.

With only one known exception (discussed below), the PPP family enzymes of eukaryotes are dedicated Ser/Thr-protein phosphatases. We were surprised to find the remarkable preference of AtRLPH2 for tyrosine phospho-peptides with activities up to 50-fold greater than with a collection of Ser/Thr phospho-peptides. With one selected tyrosine-phosphorylated peptide (rSAPK3), we demonstrated that AtRLPH2 had a Km value within the range observed for other tyrosine-specific phosphatases (36). When we changed the pTyr of this peptide to pSer or pThr, the ability of RLPH2 to dephosphorylate this substrate was almost completely abrogated, supporting the idea that AtRLPH2 is a tyrosine phosphatase.

As the kcat value toward the phospho-peptide substrate used here was only 0.053s−1, considerably less than other PTPs (36), additional factors that may influence AtRLPH2 activity should be considered. 1) AtRLPH2 may be a highly specific enzyme with only a few, currently unknown pTyr phosphorylated substrates. 2) Our assay conditions may, in some way, not be optimal for the enzyme. For example, unlike the classic PTPs, the addition of a thiol-reducing agent (DTT) had no effect on AtRLPH2 activity (data not shown). 3) AtRLPH2 requires association with additional non-substrate protein partners to achieve maximal enzymatic activity and/or to determine substrate specificity. As AtRLPH2 is a PPP family protein phosphatase, one must consider that PPP family protein phosphatases have a multitude of regulatory subunits influencing enzyme stability, activity, and/or determine substrate specificity (6, 7, 10).

We initially performed peptide assays with bacterially built and purified AtRLPH2. However, concerned that the observed AtRLPH2 pTyr phospho-peptide specificity could be an artifact of bacterial protein expression, we confirmed this preference for Tyr phospho-peptides using the enzymes expressed in planta as a TAP tag construct, and then again with the immunoprecipitated endogenous enzyme. Previous studies with other dedicated Ser/Thr and Tyr phosphatases have shown the remarkable specificity these enzymes display toward phospho-peptides, giving us confidence that the observations here reflect AtRLPH2s in vivo capabilities (28–30). Lastly, like the previously characterized plant PTP1 enzyme (11), AtRLPH2 could dephosphorylate a classic human tyrosine phosphatase substrate, in this case autophosphorylated tyrosine kinase Fer.

In support of our work with AtRLPH2 are the assays performed on the Arabidopsis PPP enzyme SLP1 (AtSLP1). Based on its sequence, it is also a Ser/Thr-protein phosphatase (16), yet it displays dual specificity activity toward pSer, pThr, and pTyr peptides. Previous work on the Plasmodium equivalents of plant SLP1 and SLP2 (SHLP1 and -2) (31, 37) indicates that, like AtRLPH2, they are resistant to okadaic acid and microcystin. Moreover, like the cold-active phosphatase originally described in Shewanella (38), SHLP2 has been shown to preferentially dephosphorylate phospho-tyrosine.

With the abundance of plant tyrosine phosphorylation, and a paucity of classic tyrosine-specific phosphatases, we demonstrate that AtRLPH2 is one of the missing components in this area of plant signaling. We also show for the first time that a member of the plant PPP family of phosphatases has the capability to dedicate its activity solely toward phospho-tyrosine. All other PPP family enzymes have rigid active sites that are Ser/Thr-specific (7). A structure for AtRLPH2 may reveal a better understanding of how this enzyme evolved to have the unique capacity to specifically dephosphorylate phospho-tyrosine.

Author Contributions

R. G. U. cloned AtRLPH2-V5-HIS6 and AtRLPH2-cTAP, and in addition performed enzymatic assays involving these proteins. R. G. U. and A. M. L. created anti-AtRLPH2 IgG, with A. M. L. responsible for a research related to the anti-AtRLPH2 IgG thereafter. A. M. L. created and performed experiments related to AtRLPH2 T-DNA knockout lines and determined kinetic parameters. J. M. and M. S. assisted A. M. L. in visualizing the subcellular localization of AtRLPH2. R. G. U., A. M. L., and G. B. M. were responsible for manuscript assembly.

Acknowledgments

We thank Nick Tonks (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory) for the GST-Fer construct. We also thank Dr. D Alessi of the Medical Research Council Protein Phosphorylation and Ubiquitylation Unit (Dundee) for several phospho-peptides used in assays.

This work was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

- PPP

- phospho-protein phosphatase(s)

- PPM

- phospho-protein metallo-phosphatase

- PTP

- phospho-tyrosine phosphatase

- RLPH

- Rhizobiales/Rhodobacterales/Rhodospirillaceae-like phosphatase

- pTyr

- phospho-tyrosine

- pSer

- phospho-serine

- pThr

- phospho-threonine

- TAP

- tandem affinity purification

- cTAP

- C-terminal TAP

- Ni-NTA

- nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid

- pNPP

- para-nitrophenylphosphate

- IP

- immunoprecipitation

- PIS

- pre-immune serum

- rSAPK3

- rat SAPK3.

References

- 1. Sharma K., D'Souza R. C., Tyanova S., Schaab C., Wiśniewski J. R., Cox J., and Mann M. (2014) Ultradeep human phosphoproteome reveals a distinct regulatory nature of Tyr and Ser/Thr-based signaling. Cell Rep. 8, 1583–1594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sugiyama N., Nakagami H., Mochida K., Daudi A., Tomita M., Shirasu K., and Ishihama Y. (2008) Large-scale phosphorylation mapping reveals the extent of tyrosine phosphorylation in Arabidopsis. Mol. Syst. Biol. 4, 193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nakagami H., Sugiyama N., Mochida K., Daudi A., Yoshida Y., Toyoda T., Tomita M., Ishihama Y., and Shirasu K. (2010) Large-scale comparative phosphoproteomics identifies conserved phosphorylation sites in plants. Plant Physiol. 153, 1161–1174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nguyen T. H., Brechenmacher L., Aldrich J. T., Clauss T. R., Gritsenko M. A., Hixson K. K., Libault M., Tanaka K., Yang F., Yao Q., Pasa-Tolić L., Xu D., Nguyen H. T., and Stacey G. (2012) Quantitative phosphoproteomic analysis of soybean root hairs inoculated with Bradyrhizobium japonicum. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 11, 1140–1155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hunter T. (2009) Tyrosine phosphorylation: thirty years and counting. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 21, 140–146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Uhrig R. G., Labandera A. M., and Moorhead G. B. (2013) Arabidopsis PPP family of serine/threonine protein phosphatases: many targets but few engines. Trends Plant Sci. 18, 505–513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shi Y. (2009) Serine/threonine phosphatases: mechanism through structure. Cell 139, 468–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tonks N. K. (2013) Protein tyrosine phosphatases: from housekeeping enzymes to master regulators of signal transduction. FEBS J. 280, 346–378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kerk D., Templeton G., and Moorhead G. B. (2008) Evolutionary radiation pattern of novel protein phosphatases revealed by analysis of protein data from the completely sequenced genomes of humans, green algae, and higher plants. Plant Physiol. 146, 351–367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Moorhead G. B., Trinkle-Mulcahy L., and Ulke-Lemée A. (2007) Emerging roles of nuclear protein phosphatases. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 234–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Xu Q., Fu H. H., Gupta R., and Luan S. (1998) Molecular characterization of a tyrosine-specific protein phosphatase encoded by a stress-responsive gene in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 10, 849–857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Luan S. (2003) Protein phosphatases in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 54, 63–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mithoe S. C., Boersema P. J., Berke L., Snel B., Heck A. J., and Menke F. L. (2012) Targeted quantitative phosphoproteomics approach for the detection of phospho-tyrosine signaling in plants. J. Proteome Res. 11, 438–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Andreeva A. V., and Kutuzov M. A. (2004) Widespread presence of “bacterial-like” PPP phosphatases in eukaryotes. BMC Evol. Biol. 4, 47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Uhrig R. G., and Moorhead G. B. (2011) Two ancient bacterial-like PPP family phosphatases from Arabidopsis are highly conserved plant proteins that possess unique properties. Plant Physiol. 157, 1778–1792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Uhrig R. G., Kerk D., and Moorhead G. B. (2013) Evolution of bacteria-like phosphoprotein phosphatases in photosynthetic eukaryotes features ancestral mitochondrial or archaeal origin and possible lateral gene transfer. Plant Physiol. 163, 1829–1843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Templeton G. W., Nimick M., Morrice N., Campbell D., Goudreault M., Gingras A. C., Takemiya A., Shimazaki K., and Moorhead G. B. (2011) Identification and characterization of AtI-2, an Arabidopsis homologue of an ancient protein phosphatase 1 (PP1) regulatory subunit. Biochem. J. 435, 73–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Meng T. C., and Tonks N. K. (2003) Analysis of the regulation of protein tyrosine phosphatases in vivo by reversible oxidation. Methods Enzymol. 366, 304–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhang X., Henriques R., Lin S. S., Niu Q. W., and Chua N. H. (2006) Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana using the floral dip method. Nat. Protoc. 1, 641–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tran H. T., Ulke A., Morrice N., Johannes C. J., and Moorhead G. B. (2004) Proteomic characterization of protein phosphatase complexes of the mammalian nucleus. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 3, 257–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tran H. T., Nimick M., Uhrig R. G., Templeton G., Morrice N., Gourlay R., DeLong A., and Moorhead G. B. (2012) Arabidopsis thaliana histone deacetylase 14 (HDA14) is an α-tubulin deacetylase that associates with PP2A and enriches in the microtubule fraction with the putative histone acetyltransferase ELP3. Plant J. 71, 263–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ulke-Lemée A., Trinkle-Mulcahy L., Chaulk S., Bernstein N. K., Morrice N., Glover M., Lamond A. I., and Moorhead G. B. (2007) The nuclear PP1 interacting protein ZAP3 (ZAP) is a putative nucleoside kinase that complexes with SAM68, CIA, NF110/45, and HNRNP-G. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1774, 1339–1350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Labandera A. M., Vahab A. R., Chaudhuri S., Kerk D., and Moorhead G. B. (2015) The mitotic PP2A regulator ENSA/ARPP-19 is remarkably conserved across plants and most eukaryotes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 458, 739–744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Silver D. M., Silva L. P., Issakidis-Bourguet E., Glaring M. A., Schriemer D. C., and Moorhead G. B. (2013) Insight into the redox regulation of the phosphoglucan phosphatase SEX4 involved in starch degradation. FEBS J. 280, 538–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Baykov A. A., Evtushenko O. A., and Avaeva S. M. (1988) A malachite green procedure for orthophosphate determination and its use in alkaline phosphatase-based enzyme immunoassay. Anal. Biochem. 171, 266–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Samajová O., Komis G., and Samaj J. (2014) Immunofluorescent localization of MAPKs and colocalization with microtubules in Arabidopsis seedling whole-mount probes. Methods Mol. Biol. 1171, 107–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gordon J. A. (1991) Use of vanadate as protein-phosphotyrosine phosphatase inhibitor. Methods Enzymol. 201, 477–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Donella Deana A., Mac Gowan C. H., Cohen P., Marchiori F., Meyer H. E., and Pinna L. A. (1990) An investigation of the substrate specificity of protein phosphatase 2C using synthetic peptide substrates: comparison with protein phosphatase 2A. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1051, 199–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Donella-Deana A., Meyer H. E., and Pinna L. A. (1991) The use of phosphopeptides to distinguish between protein phosphatase and acid/alkaline phosphatase activities: opposite specificity toward phosphoseryl/phosphothreonyl substrates. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1094, 130–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Donella-Deana A., Boschetti M., and Pinna L. A. (2003) Monitoring of PP2A and PP2C by phosphothreonyl peptide substrates. Methods Enzymol. 366, 3–17 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fernandez-Pol S., Slouka Z., Bhattacharjee S., Fedotova Y., Freed S., An X., Holder A. A., Campanella E., Low P. S., Mohandas N., and Haldar K. (2013) A bacterial phosphatase-like enzyme of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum possesses tyrosine phosphatase activity and is implicated in the regulation of band 3 dynamics during parasite invasion. Eukaryot. Cell 12, 1179–1191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ruzzene M., Donella-Deana A., Marin O., Perich J. W., Ruzza P., Borin G., Calderan A., and Pinna L. A. (1993) Specificity of T-cell protein tyrosine phosphatase toward phosphorylated synthetic peptides. Eur. J. Biochem. 211, 289–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Oh M. H., Wu X., Kim H. S., Harper J. F., Zielinski R. E., Clouse S. D., and Huber S. C. (2012) CDPKs are dual-specificity protein kinases and tyrosine autophosphorylation attenuates kinase activity. FEBS Lett. 586, 4070–4075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nemoto K., Takemori N., Seki M., Shinozaki K., and Sawasaki T. (2015) Members of the plant CRK superfamily are capable of trans- and autophosphorylation of tyrosine residues. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 16665–16677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Huang Y., Li H., Gupta R., Morris P. C., Luan S., and Kieber J. J. (2000) ATMPK4, an Arabidopsis homolog of mitogen-activated protein kinase, is activated in vitro by AtMEK1 through threonine phosphorylation. Plant Physiol. 122, 1301–1310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhang Z. Y., Thieme-Sefler A. M., Maclean D., McNamara D. J., Dobrusin E. M., Sawyer T. K., and Dixon J. E. (1993) Substrate specificity of the protein tyrosine phosphatases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 4446–4450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Patzewitz E. M., Guttery D. S., Poulin B., Ramakrishnan C., Ferguson D. J., Wall R. J., Brady D., Holder A. A., Szöőr B., and Tewari R. (2013) An ancient protein phosphatase, SHLP1, is critical to microneme development in Plasmodium ookinetes and parasite transmission. Cell Rep. 3, 622–629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tsuruta H., Mikami B., and Aizono Y. (2005) Crystal structure of cold-active protein-tyrosine phosphatase from a psychrophile, Shewanella sp. J. Biochem. 137, 69–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cheng Y. T., Germain H., Wiermer M., Bi D., Xu F., García A. V., Wirthmueller L., Després C., Parker J. E., Zhang Y., and Li X. (2009) Nuclear pore complex component MOS7/Nup88 is required for innate immunity and nuclear accumulation of defense regulators in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 21, 2503–2516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]