Abstract

Gendered occupational segregation remains prevalent across the world. Although research has examined factors contributing to the low number of women in male-typed occupations – namely science, technology, engineering, and math – little longitudinal research has examined the role of childhood experiences in both young women’s and men’s later gendered occupational attainment. This study addressed this gap in the literature by examining family gender socialization experiences in middle childhood – namely parents’ attitudes and work and family life – as contributors to the gender typicality of occupational attainment in young adulthood. Using data collected from mothers, fathers, and children over approximately 15 years, the results revealed that the associations between childhood socialization experiences (∼10 years old) and occupational attainment (∼26 years old) depended on the sex of the child. For sons but not daughters, mothers’ more traditional attitudes towards women’s roles predicted attaining more gender-typed occupations. In addition, spending more time with fathers in childhood predicted daughters attaining less and sons acquiring more gender-typed occupations in young adulthood. Overall, evidence supports the idea that childhood socialization experiences help to shape individuals’ career attainment and thus contribute to gender segregation in the labor market.

Keywords: career development, childhood, family socialization, gender, occupational attainment, young adulthood

Gendered occupational segregation remains prevalent across the world (Charles, 2011): Women are more likely to hold occupations related to education, health, and clerical work, whereas men are found more often in managerial, science, engineering, and physically demanding jobs such as construction (Steinmetz, 2012). Gendered occupational attainment has corresponding social problems. First, it can prevent workers from choosing occupations in which they could perform well, which in turn deprives society and employers of skill and talent and is economically inefficient. Second, it contributes to the gender wage gap by excluding women from occupations that are better-paid than female-dominated occupations (Hegewisch et al., 2010). Third, women are less likely than men to hold high prestige positions – 77.8% of chief executives and legislators are male, for example (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010)—which contributes to gender differences in power and influence within a society. Fourth, the availability of many blue-collar male-typed jobs (e.g., manufacturing) in the U.S. has dropped due to economic restructuring – leaving fewer available positions for men.

Research on gender segregation in the labor market has focused on why women are not pursuing STEM careers. This is important given that the nation’s ability to be competitive in the global economy is dependent on STEM achievements. This focus, however, ignores another important question – why aren’t men pursuing female-typed occupations? The limited research may be because male-typed occupations have been more prestigious and/or higher paid. Economic restructuring, however, has led to declines in wages and job growth among many blue-collar, male-typed occupations (Shen-Miller & Smiler, 2015), and male-typed occupations tend to be more dangerous than female-typed occupations (Stier & Yaish, 2014). Thus, it also is important to understand contributors to men’s gender atypical occupational choices. This study used longitudinal data to examine early roots of gendered occupational attainment, namely parents’ gender attitudes and work and family life when their children were about 10 years old.

Theoretical Underpinnings: The Role of Parents

Gender socialization refers to the transmission of norms, behaviors, values, and skills necessary to be a “successful” woman or man. Parents socialize gender in many ways: they are models, reinforce/punish children’s behaviors, select children’s environments and shape opportunities within those environments, and scaffold children’s skill development (Bornstein et al., 2011). For example, parents’ work and family experiences, such as the time each parent spends in housework and paid employment, are observed and may be models for children’s later choices (Bussey & Bandura, 1999). Parents’ gender role attitudes also influence the ways they socialize their children. Bornstein and colleagues (2011) argue that parents with traditional gender role attitudes encourage and set expectations that their sons behave in stereotypically masculine ways, which may lead to children’s internalization of these attitudes and expectations.

Parents’ socialization practices, in turn, may influence their children’s beliefs about their future work success and whether or not they value gender atypical work. According to the expectancy-value theory of achievement (EVT), individuals who believe that they can be successful in and value the tasks associated with gender atypical occupations are the most likely to pursue them (Wigfield & Eccles, 2000). This theory posits that parents’ beliefs and behaviors influence children’s values, expectations, and interpretations of achievement-related experiences, which contribute to children’s goals and self-schemas, and ultimately play a role in occupational attainment. Thus, we examined parents’ attitudes, work, and family roles as contributors to children’s gendered occupational attainments.

Parental Influences on Children’s Vocational Development

Over 25 years ago, Corcoran and Courant (1987) recommended that researchers use longitudinal data to illuminate the role of early socialization experiences in adults’ gendered occupational attainment. Yet, longitudinal data remain limited. Instead, most studies assess concurrent associations between parents’ characteristics and their children’s occupational aspirations. Below we summarize findings on associations between parents’ gender role attitudes and work and family life with children’s occupational aspirations and then consider the limited longitudinal data on parents’ influences on their children’s occupational attainment.

Parental Gender Role Attitudes

Mothers’ traditional gender role attitudes have been linked to the gender typicality of adolescent daughters’ desired careers (Fiebig & Beauregard, 2011). Less attention has been given to fathers’ gender role attitudes, although some early evidence suggests that these may not be related to daughters’ gender typicality (Steele & Barling, 1996). We also know little about the role of parents’ gender role attitudes and sons’ occupational aspirations. Research has, however, supported the role of parents’ attitudes posited by the EVT: More traditional mothers overestimated their children’s skills in gender-typed domains, which, in turn, were associated with children’s perceptions of their abilities. These perceptions have implications for youths’ occupational aspirations and attainment (Wigfield & Eccles, 2000).

Work Life

Research suggests that parents’ occupations influence socialization practices, indirectly influencing children’s occupational aspirations through their interests and skills (Ryu & Mortimer, 1996). Further, more gender-typed occupations of mothers (but not fathers) were linked to daughters’ gender-typed occupational aspirations (Barak, Feldman, & Noy, 1991), a pattern not apparent for sons. In contrast, studying an ethnically and socioeconomically diverse sample, Schuette and colleagues (2012) found that the gender typicality of mother figures’ occupations was unrelated to girls’ desired occupations, but that boys’ occupational aspirations were linked to the gender typicality of father figures’ occupations.

Family Life

Mothers typically spend more time in housework than fathers (Bianchi, Milkie, Sayer, & Robinson, 2000). A less traditional division of household work by parents, however, is associated with less gender-typed role preferences (including occupational preferences), interests, and less knowledge of and adherence to gender stereotypes in childhood (McHale, Crouter, & Tucker, 1999; Serbin et al., 1993).

Parent-child time together may also have implications for occupational aspirations – and that association may depend on the sex composition of the parent-child dyad. On average, mothers spend more time with their children than fathers (Craig, 2006), and mothers and fathers engage in and encourage different kinds of activities: Fathers tend to encourage more risk-taking, exploration, active leisure, and taking initiative, whereas mothers tend to engage in more role-playing, object-mediated play, and child care (Lam & McHale, 2014; Paquette, 2004; Sayer et al., 2004). Thus, paternal involvement may expose children to a range of experiences and skill-building opportunities, which, according to EVT, have implications for occupational aspirations (Wigfield & Eccles, 2000). However, social pressures toward boys’ stereotypically masculine orientations may mean that fathers discourage sons from exploring female-typed interests, skills, and careers. Indeed, time with fathers in childhood was associated concurrently with less gender-typed occupational aspirations for daughters but more gender-typed aspirations for sons in an early study of school-aged children (Baruch & Barnett, 1986). In this study we tested whether these same kinds of patterns emerged in longitudinal associations between parent-child shared time in middle childhood and young adults’ occupational attainment.

Longitudinal Research on Youth Occupational Attainment

Few longitudinal studies have examined early family socialization influences on adult occupations attainment, and even fewer have focused on childhood experiences. One study revealed no links between mothers’ relative to fathers’ labor force involvement in adolescence and young women’s gendered occupational attainment (Corcoran & Courant, 1987), but young adults’ retrospective reports highlighted mothers and fathers as primary influences on career achievement (Helwig, 2008).

Longitudinal data from the Michigan Study of Adolescent Life Transitions showed that parents’ attitudes predicted their children’s occupational attainment in young adulthood: Sons whose mothers reported more gender traditional attitudes in adolescence were more likely to acquire male-typed occupations in young adulthood, and parents’ gender typical occupation expectations in adolescence were associated with their children’s more gender-typed occupations in young adulthood (Chhin, Bleeker, & Jacobs, 2008).

Directions for Research

Some limitations of prior literature provided the impetus for the present study. First, childhood is a key time of exploration and learning when an awareness of work and sense of self are developing, which result in an individual’s vocational identity and self-concept (Porfeli, Hartung, & Vondracek, 2008). As such, longitudinal data beginning in childhood “before gendered conceptions of the world of work crystallize” (p. 29) are essential for understanding and ultimately reducing the gendered segregation of the workforce.

Second, consistent with social learning tenets that such intergenerational transmission will be strongest, prior work focuses on same-sex parent-child dyads (Bussey & Bandura, 1999). Thus, most research includes only one parent, and although past research focused on sons, recent studies target daughters’ occupational attainment. There is some evidence, however, that opposite-sex parents also have implications for their offspring’s occupational attainment. For example, Chhin and colleagues (2008) found that mothers’, not fathers’, gender role attitudes predicted sons’ more male-typed occupations. Relatedly, data are usually collected from only one person – typically the child (Schuette et al., 2012): When youth report on both their own and their mothers’ and/or fathers’ gender orientations, mono-reporter bias may inflate correlations. Thus, in this study we collected data from mothers and fathers about dimensions of gender socialization and data from both sons and daughters about their gendered occupation attainment.

Finally, much of the literature on the role of the gendered division of household labor on children’s outcomes was conducted in the 1990s – nearly 15 to 25 years ago. Given changes in both gender roles (Kite, 2001) and the labor market (Shen-Miller & Smiler, 2015), research on contemporary patterns is needed.

Present Study

In sum, this study was aimed at contributing to the literature by using longitudinal data starting in childhood and collected from mothers, fathers, sons, and daughters to assess both same-sex and cross-sex links between parents’ gendered attitudes and work and family life and the gendered occupational attainment of their children in young adulthood. Specifically, we examined parents’ gender role attitudes, hours worked per week, gender typicality of occupation, and time spent on female-typed household labor and with children when children were about 10 years old as predictors of the gender typicality of children’s occupational attainment at about age 26. We hypothesized that parents’ more gendered attitudes and patterns of work and family life would predict more gender-typed occupational attainment in young adulthood, and that these associations would be strongest for same-sex parent-child dyads.

Material and Methods

Participants

Data from a longitudinal study of family socialization were used to address the research goals. The sample included mothers, fathers, and children from 203 families residing in a Northeastern state. Families were recruited via letters sent home from schools in 16 districts. Families with a firstborn child in the fourth or fifth grade, two opposite-sex, always-married, employed parents, and who were interested in participating in the study returned a postcard to the project office. Over 90% of the eligible families who returned postcards and met criteria agreed to participate in the study. Although data were collected from both firstborn and secondborn children (beginning in 1995–1996), the current study focused on firstborn children because a majority of secondborn children were still in school at the young adulthood follow-up.

Data were collected in home interviews on up to 10 annual occasions (until the year after firstborns graduated from high school, and then in a web survey about 6 years later). A total of 203 first-born children completed phase 1 assessments and 157 completed phase 11 – the two phases used for the current study. T-tests and chi-square analyses revealed that phase 11 participants did not differ from those who did not participate at phase 11 on demographics (children’s age, gender, income, family size, and employment status) except parent age and education. At baseline, parents of young adults who did not participate at phase 11 were significantly younger, mothers: 34.99 v. 37.14, t(199) = −3.29, p < .01; fathers: 37.15 v. 39.42, t(199) = −2.70, p < .01, and less educated (12 = High school graduate, 16 = College Degree), mothers: 13.80 v. 14.78, t(199) = −2.74, p < .01; fathers: 13.86 v. 14.90, t(199) = −2.53, p < .01.

Children (N = 123) employed at phase 11 were included in the analyses (Table 1). Almost all participants were White (99.19%), approximately half (52.85%) were female, and participants averaged 10.87 years at phase 1 and 26.25 years at phase 11. The highest level of education included: 22.77% high school diploma, 8.94% Associates degree, 52.85% college degree, 10.57% Master’s degree, and 4.88% professional degree. At phase 1, fathers and mothers were on average 38.88 and 36.65 years, 37% of the families had an annual household income of less than $50,000, 43% between $50–75,000, and only 20% had incomes greater than $75,000. Half the parents (51.38% of fathers, 56.67% of mothers) did not have a Bachelor’s degree.

Table 1.

Child, Parent, and Family Demographic Characteristics during Middle Childhood and Young Adulthood: Mean (SD) or N (%)

| Middle Childhood (Phase 1) |

Young Adulthood (Phase 11) |

Current Study Sample |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | 203 | 157 | 123 |

| Child characteristics | |||

| Age | 10.87 (.54) | 26.26 (.80) | 26.25 (.81) |

| Gender (% Female) | 105 (51.72%) | 85 (54.14%) | 65 (52.85%) |

| Occupational attainment in young adulthood | |||

| N (%) Student Only | -- | 12 (7.69%) | 0 (0.00%) |

| N (%) Unemployed | -- | 8 (5.13%) | 0 (0.00%) |

| N (%) Student & Working | -- | 24 (15.38%) | 12 (9.76%) |

| N (%) Only Working | -- | 112 (71.94%) | 111 (90.24%) |

| Mother characteristics | |||

| Age | 36.65 (3.94) | 52.62 (3.86) | 52.38 (3.65) |

| Education | 14.58 (2.15) | 15.13 (2.19) | 15.05 (2.12) |

| Employment (% employed) | 186 (91.63%) | 133 (86.36%) | 105 (86.78%) |

| Father characteristics | |||

| Age | 38.88 (5.00) | 54.88 (5.23) | 54.75 (5.51) |

| Education | 14.67 (2.43) | 15.29 (2.30) | 15.05 (2.14) |

| Employment (% employed) | 203 (100%) | 134 (94.37%) | 103 (94.50%) |

| Family characteristics | |||

| Ethnicity (% White) | 202 (99.51%) | 156 (99.36%) | 122 (99.19%) |

| Family (i.e., parents’) income | 60,233 (28,473) | 115,993 (90,375) | 117,664 (99,882) |

Note. Education was coded in years: 12 = High school graduate, 14 = Associates Degree, 16 = College Degree, 20 = PhD.

Procedure

In the phase 1 home interviews, parents reported on their gender attitudes and work and family life. In the web surveys at phase 11, young adults reported their current occupation. In addition, we used data from daily telephone surveys to assess family members’ time use in phase 1. Youth completed seven evening telephone interviews (five weekdays, two weekend days) and parents each completed four evening interviews (three weekdays, one weekend day) during the three to four weeks following the home interview. Children and parents’ data were only included if they completed all of the phone calls. For the current study sample, all parents and children completed every phone call. On each call, family members reported on the duration of time spent on specific activities that day (e.g., wash dishes) and their companions in each activity. Calls were conducted during the evening so that a majority of the day’s activities could be reported.

Materials

Gender Typicality of Children’s Occupations

During phase 11, young adults reported their current occupation and education. Occupations were coded if the participant was not currently in school or if the schooling was related to the current occupation (e.g., an elementary teacher earning a Master’s degree in education). If a participant was in school and currently working in an occupation that was not a long-term occupation related to current schooling, the occupation was coded as missing (e.g., a student majoring in Media Studies who was working as a bartender). Two independent coders agreed 76.8% of the time on whether the occupation should be considered “long-term” and coded. The coders discussed all disagreements to make the final decisions. Out of the total 157 individuals who completed the phase 11 assessment, 123 occupations (65 females, 58 males) were coded (14 females and 9 males were still in school, 5 females and 3 males were unemployed, and 1 female and 1 male did not give enough information about the occupation to be coded). Gender typicality was coded based on the percent of females in each occupation using data from the U.S. Census Bureau (2000). To assess reliability, a second individual coded 10% of the occupations (84.6% agreement). To avoid loss of information and to maintain statistical power, we treated the measure of gender-typed occupational choice as a continuous measure (Royston et al., 2006).

Parent Characteristics

At phase 1, parents’ gender role attitudes were assessed using Spence & Helmreich’s (1978) Attitudes Toward Women (ATW) scale. Parents completed 15 items assessing attitudes toward the roles of women versus men using a 4-point scale (1 = Strongly Agree, 4 = Strongly Disagree; example item: “Women should be able to work as equals with men in all businesses and professions”). Items were summed; higher scores reflected more traditional attitudes (Cronbach’s alpha= .74 for fathers and .82 for mothers). This scale is a commonly used measure of attitudes toward women’s and men’s work and family roles, with substantiating evidence of its reliability and validity (Beere, 1990).

Work hours per week and the gender typicality of parents’ occupations at phase 1 were used to capture parents’ work life. Parents reported the total hours working at the job plus hours spent at home on work-related activities (e.g., a teacher grading assignments) in a typical week – which were summed to create the work hours variable. The gender typicality of mothers’ and fathers’ occupations was coded in the same way as young adults’: based on the percent of females in the U.S. (U.S. Census Bureau, 2000). To assess reliability, a second individual coded 10% of parents’ occupations (70.7% agreement between coders). A total of 15 mothers reported that they were homemakers. Because the U.S. Census Bureau only contains information about paid employment, we used data from the first wave of the National Survey of Midlife Development in the United States (MIDUS) collected from 1995 to 1996, which includes a nationally representative sample (Brim, Ryff, & Kessler, 2004). In that study, 97.6% of homemakers were female and thus we used this as the gender typicality score of homemaking.

Time spent on female-typed household tasks and with children was used to index parents’ family life. Mothers and fathers reported on their time in four female-typed household tasks during the 4 telephone calls (do dishes; prepare a meal or snack; vacuum, dust, or straighten up; laundry), and these reports were summed across days. To measure parent-child time together, children reported the amount of time they engaged in 70 different activities (e.g., eating meals, working on homework) and whether their mothers and/or fathers were present during those activities. The number of minutes reported with parents were summed across the 7 days of the children’s telephone calls separately for mothers and fathers. Past research using this sample has found evidence of accurate reporting: Inter-rater agreement has been found between mothers and fathers’ (r = .77) and between children and parents’ reports of joint activities on the same day (r = .52 to .65; McHale et al., 1999). In addition, daily measures are less prone to errors such as memory recall issues (Iida et al., 2012).

Covariates included parents’ education, children’s male-typed and female-typed interests at phase 1, and child gender (0 = girl, 1 = boy). Because parents’ socioeconomic status is a significant predictor of occupational attainment (Schuette et al., 2012), the average of mothers’ and fathers’ education was included as a covariate (mothers’ and fathers’ education levels were correlated, r = .58). In addition, children’s male- and female-typed interests at phase 1 were added as covariates to ensure that parents’ characteristics were not associated with the gender typicality of children’s occupations due to the fact that parents adjusted their attitudes or behaviors based on their children’s early interests. Gender-typed interests were measured using a scale adapted from Huston, McHale, and Crouter (1985). Children used a 4-point scale to rate their interest in 31 activities (1 = Not interested at all, 4 = Very interested). Items were categorized as male- and female-typed interested based on past research (McHale et al., 2009), which used gender differences in mothers’ and fathers’ ratings of these same interests at phase 1. Interests were coded as female-typed (11 items, e.g., dancing, handicrafts) if mothers reported significantly more interest in the activity than fathers, whereas interests were coded as male-typed (7 items, e.g., sports, hunting) if fathers reported significantly more interest in the activity than mothers. Items were averaged to create female- and male-typed interests scores. This approach to determining the gendered nature of the activities was used instead of measuring internal consistency, for example, because this scale is a menu of possible gendered activities in which children may be interested, and we would not expect that a child who was very interested in playing sports would necessarily be very interests in hunting or building, even though all are stereotypically masculine by our assessment. Evidence of the validity of the measure is that children’s self-rated interests predict children’s actual participation (as measured using time diary data; McHale et al., 2004). In addition, even though the gender-typing of interests is socially constructed and so varies across time and place, there is substantial cross-time stability (cross-time coefficients: r = .51 for feminine, r = .65 masculine interests; McHale et al., 2009).

Analyses

Separate regression models were conducted for mother and father predictors. After an initial main effects model, child gender was added as a moderator. Prior to the analyses, the males’ gender typicality scores were recoded so that higher scores reflected more gender-typed occupations for both males and females. For example, if a young man reported working in an occupation in which 10% of employees were female, the man’s score was recoded to 90%, which indicates that 90% of the employees were male.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Mother-father comparisons revealed that mothers reported less traditional attitudes, t(122) = −3.47, p < .001, d = .36, worked fewer hours outside the home, t(122) = −10.54, p < .001, d = 1.42, held more female-typed occupations, t(119) = 15.10, p < .001, d = 1.97, spent more time on female-typed household tasks, t(122) = 3.02, p < .01, d = 1.81 (Table 2), and spent more time with children, t(122) = 3.32, p < .01, d = .27. Children’s female-typed interests were positively associated with female-typed occupations, r(63) = .29, p < .05, but daughters’ male-typed interests and parents’ education at phase 1 were not associated with their occupational gender typicality. For sons, parental education was positively associated with attaining more female-typed occupations, r(56) = .28, p < .05, but male-typed and female-typed interests did not predict the gender typicality of sons’ occupations at the bivariate level.

Table 2.

Descriptive Data for Parent Attitudes, Work Life, Family Life, and Parent-Child Relationship Qualities during Middle Childhood

| Mean (SD) | N | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender role attitudes | ||

| Mother | 25.79 (6.72) | 123 |

| Father | 28.01 (5.71) | 123 |

| Work life | ||

| Mothers’ work hours (weekly) | 27.29 (16.21) | 123 |

| Fathers’ work hours (weekly) | 46.78 (10.60) | 123 |

| Mothers’ occupation gender typicality |

75.49 (23.99) | 120 |

| Fathers’ occupation gender typicality |

68.51 (23.41) | 123 |

| Family life | ||

| Mothers’ time spent on female-typed household labor (minutes/4 days) |

459.13 (245.96) | 123 |

| Fathers’ time spent on female-typed household labor (minutes/4 days) |

118.17 (103.90) | 123 |

| Mother time with child (minutes/7 days) | 677.07 (309.48) | 123 |

| Father time with child (minutes/7 days) | 598.24 (283.15) | 123 |

Note. The sample means include families with a child who reported his/her occupation in young adulthood (N = 123). Higher scores signify more traditional attitudes. Gender typicality was coded as the percent of women in an occupation, but fathers’ scores were reverse-coded so that higher scores reflected more gender-typed occupations for both mothers and fathers.

Family Gender Socialization and Young Adults’ Gendered Occupations

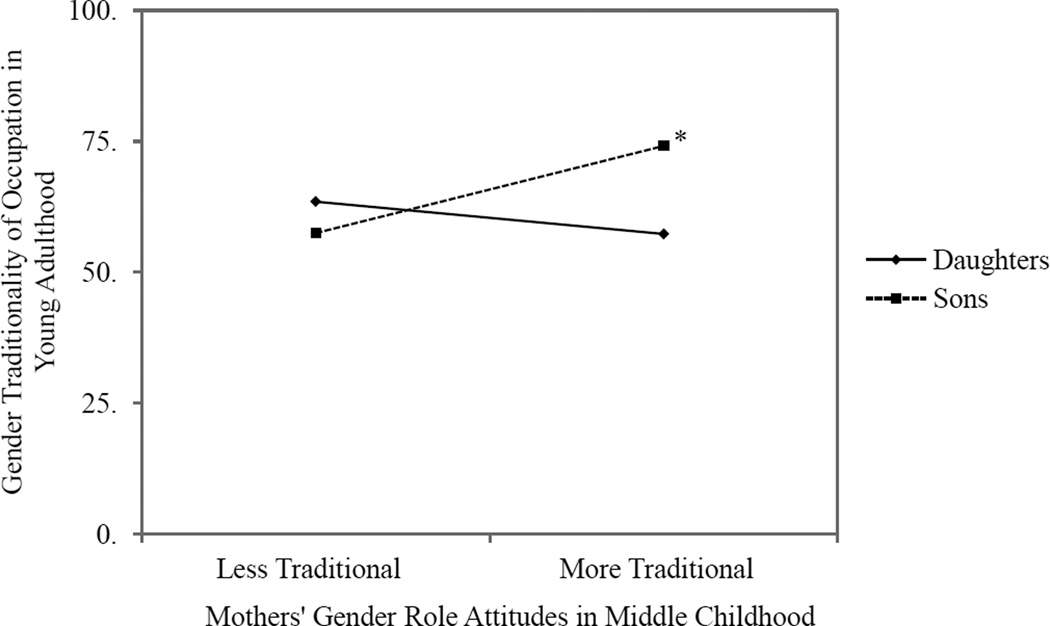

Beginning with findings for mothers, there were no significant main effects of maternal attitudes or work/family life on the gender typicality of young adults’ occupations (Table 3), but child gender moderated the effects of attitudes, β = .29, p < .05, and time spent with children, β = .27, p < .05. For sons only, more traditional maternal attitudes, β = .32, p < .05, predicted attainment of more gender-typed occupations over 15 years later. Follow-up analyses also indicated that boys spending more time with their mother was associated with attaining more gender-typed occupations, β = .20, p < .10, although this association was not statistically significant.

Table 3.

Standardized and Unstandardized Coefficients (and SEs) from Regression Analyses Examining Mothers’ Attitudes, Work Life, and Family Life during Middle Childhood as Predictors of the Gender Typicality of Occupational Attainment in Young Adulthood

| Main Effect Model | Child Gender Moderation Model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized | Unstandardized (SE) |

Standardized | Unstandardized (SE) |

|

| Covariates | ||||

| Child gender | .09 | 4.39 (6.74) | .10 | 4.87 (6.53) |

| Parent education | −.24* | −3.29 (1.35) | −.19* | −2.71 (1.32) |

| Male-typed interests | −.00 | −.09 (5.99) | .02 | .95 (5.82) |

| Female-typed interests | .04 | 2.21 (5.99) | .07 | 3.61 (5.77) |

| Main effects | ||||

| Intercept | 0.00 | 61.37 (3.76) | 0.00 | 60.53 (3.67) |

| Gender role attitudes | .07 | .25 (.37) | −.12 | −.46 (.45) |

| Work hours | −.03 | −.05 (.16) | .02 | .02 (.20) |

| Gender typicality of occupation | .01 | .01 (.10) | .24t | .25 (.14) |

| Time in female-typed household tasks | −.09 | −.01 (.01) | −.19 | −.02 (.01) |

| Time with child | .04 | .00 (.01) | −.15 | −.01 (.01) |

| Interactions | ||||

| Gender role attitudes*child gender | - | - | .29* | 1.70 (.73) |

| Work hours*child gender | - | - | −.02 | −.05 (.31) |

| Gender typicality of occupation*child gender |

- | - | −.25t | −.36 (.19) |

| Time in female-typed household tasks*child gender |

- | - | .13 | .02 (.02) |

| Time with child*child gender | - | - | .27* | .03 (.01) |

| Adjusted R2 | .01 | .10 | ||

Note. Gender typicality was coded as the percent of women in an occupation, but men’s scores were reverse-coded so that higher scores reflected more gender-typed occupations for both young men and women.

< .10,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

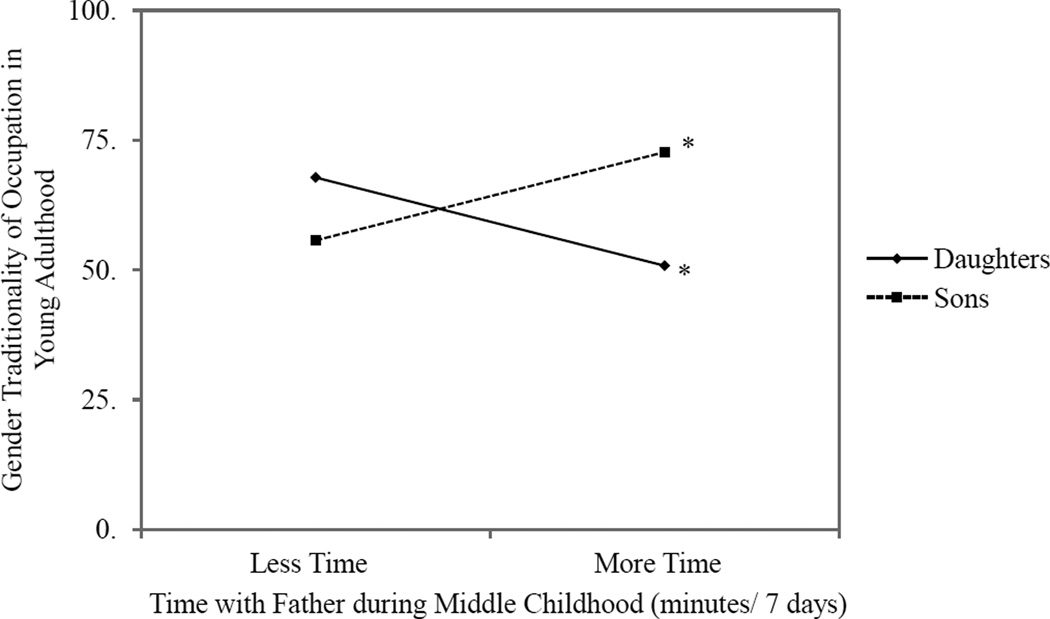

In the case of fathers, no significant main effects of parents’ attitudes and behaviors emerged (Table 4). Child gender, however, moderated the association between fathers’ time with children and the gender typicality of young adults’ occupations, β = .50, p < .001. For daughters, spending more time with fathers during childhood predicted less gender-typed occupations in young adulthood, β = −.36, p < .01. In contrast, sons who spent more time with their fathers obtained more gender-typed occupations as young adults, β = .29, p < .05. In other words, both sons and daughters obtained more male-typed occupations in young adulthood when fathers spent more time with them in childhood.

Table 4.

Standardized and Unstandardized Coefficients (SEs) from Regression Analyses Examining Fathers’ Attitudes, Work Life, and Home Life during Middle Childhood as Predictors of the Gender Typicality of Occupational Attainment in Young Adulthood

| Main Effect Model | Child Gender Moderation Model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized | Unstandardized (SE) |

Standardized | Unstandardized (SE) |

|

| Covariates | ||||

| Child gender | .12 | 6.20 (6.60) | .09 | 4.44 (6.43) |

| Parent education | .17t | −2.36 (1.36) | −.12 | −1.76 (1.33) |

| Male-typed interests | −.00 | −.05 (5.84) | .09 | 4.24 (5.74) |

| Female-typed interests | .06 | 3.18 (5.74) | .07 | 3.89 (5.63) |

| Main Effects | ||||

| Intercept | 0.00 | 61.13 (3.61) | 0.00 | 59.52 (3.55) |

| Gender role attitudes | .15 | .65 (.43) | .10 | .43 (.56) |

| Work hours | .06 | .15 (.22) | −.03 | −.08 (.28) |

| Gender typicality of occupation | .01 | −.02 (.10) | .04 | .05 (.14) |

| Time in female-typed household tasks | −.17t | −.04 (.02) | −.07 | −.02 (.03) |

| Time with child | −.03 | −.00 (.01) | −.38** | −.03 (.01) |

| Interactions | ||||

| Gender role attitudes*child gender | - | - | .16 | .99 (.87) |

| Work hours*child gender | - | - | .23t | .80 (.46) |

| Gender typicality of occupation*child gender |

- | - | −.11 | −.19 (.20) |

| Time in female-typed household tasks*child gender |

- | - | −.00 | −.00 (.05) |

| Time with child*child gender | - | - | .50*** | .06 (.02) |

| Adjusted R2 | .08 | .16 | ||

Note. Gender typicality was coded as the percent of women in an occupation, but men’s scores were reverse-coded so that higher scores reflected more gender-typed occupations for both young men and women.

< .10,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Discussion

Scholars, educators, business leaders, and government officials have called for a better understanding of why individuals tend to limit their career choices based on gender – particularly why women are less likely to work in the STEM fields. The present study, which was grounded in social learning theory and the EVT (Bornstein, 2011; Wigfield & Eccles, 2000), found evidence that family gender socialization experiences in childhood may play a role in the gendered segregation of the labor market.

Most research on family socialization and gendered occupational segregation has examined concurrent associations between parents’ behaviors and personal qualities and their children’s expected or desired occupations. This study sheds light on the longitudinal links between childhood family gender socialization experiences and both women’s and men’s gendered occupational attainment. The results indicated that mothers’ traditional attitudes and both mothers’ and fathers’ time with sons in childhood predicted young men holding more gender-typed jobs in their mid-20s. By contrast, young women who spent more time with their fathers attained less gender-typed occupations. In other words, both men and women who spent more time with their fathers attained more male-typed occupations in young adulthood. These results support social learning theory in suggesting that parents’ time with their children has implications for children’s vocational achievement.

As previously noted, there is little research against which to directly compare these results, given the paucity of longitudinal studies. Our results that mothers’ gender attitudes have implications for sons’ occupational attainment support past longitudinal research on mothers’ attitudes in adolescence and youth occupational attainment (Chhin et al., 2008). This finding also contributes to the literature by testing the hypothesis that intergenerational transmission is strongest for same-sex dyads (Bussey & Bandura, 1999). Although some work suggests that fathers play a role in their daughters’ aspirations and attainment of less gender-typed occupations (Whiston & Keller, 2004), little research has focused on the mother-son dyad. Our results provide evidence that mothers play a role in sons’ occupational attainment – both by virtue of their gender role attitudes and the amount of mother-son time together. Surprisingly, mothers’ time with daughters and gender role attitudes were not associated with daughters’ occupations – in direct contrast with research conducted by Fiebig and Beauregard (2011) on adolescents. Given that our study examined longitudinal linkages of parents’ characteristics with children’s actual occupational attainment – as opposed to concurrent associations of these constructs reported only by children, it is not surprising that our results differ. Although these findings support social learning theory in that parents appear to be socializers of their children, it calls into question the idea that intergenerational transmission is strongest for same-sex dyads.

Nearly 30 years ago, Baruch and Barnett (1986) found concurrent associations between time spent with fathers in childhood and both sons’ and daughters’ preferences for more male-typed occupations. Our study built on these findings by examining longitudinal associations and measuring actual occupational attainment. In addition, we controlled for children’s early gender-typed interests and parents’ education as potential “third variables” that could explain the observed associations. It is possible, for example, that fathers spent time with children who had more male-typed interests. By controlling for interests, we can conclude that, beyond the effects of children’s own qualities, father-child time together predicted young adults attaining more male-typed occupations. Despite the more rigorous methodology used in the current study, we found similar results to Baruch and Barnett (1986). Future analyses of parents’ cross gender activities could shed light on whether the nature of the activities children undertake with their parents has implications for children’s later occupational attainment, which would provide further evidence that social learning theory is underlying this intergenerational transmission.

Surprisingly, no significant associations were found between mothers’ and fathers’ work life and children’s occupational attainment. Although not significant, some findings were in the expected direction: daughters whose mothers had more female-typed occupations and sons whose fathers worked longer hours attained more gender-typed occupations. These patterns are consistent with previous findings that the gender typicality of mothers’ (Barak et al., 1991) and father figures’ occupations (Schuette et al., 2012) were associated with children’s occupational aspirations. In the present study, parents reported on their work, and children may not have directly observed their parents in their work activities. Social cognitive learning theory asserts that observation is a critical component in order for learning to occur (Bussey & Bandura, 1999). In addition, occupational aspirations and attainment are distinct constructs, with the latter being subject to a range of practical and logistical constraints and opportunities, including those emanating from beyond the family of origin, such as the nature of the economy at the time the young adult is seeking an occupation and the creation of new and outsourcing of old occupations within a society (Duffy & Dik, 2009). Because of this, aspirations may be more strongly associated with socialization experiences than is occupational attainment, requiring a larger sample size and greater power to detect smaller effects.

Strengths and Limitations

This study contributed to the literature on gendered occupational attainment in several ways. A primary strength was the use of longitudinal data spanning approximately 15 years such that we were able to test the predictive associations between childhood family experiences and young adults’ occupations. Second, data were collected from multiple family members, decreasing the possibility that mono-reporter biases explained observed associations and allowing for same-sex and cross-sex parent-child linkages to be examined. Third, the linkages of interest were statistically significant even after controlling for children’s early gender-typed interests and parents’ education, “third variables” that otherwise might have explained both childhood socialization experiences and young adult outcomes. Finally, our study moved beyond the past focus on individuals from higher socioeconomic backgrounds to include youth and families from both working- and middle-class backgrounds (e.g., at phase 1, approximately half the parents did not have a Bachelor’s degree).

In the face of these strengths, limitations of this study provide directions for future research. First, the sample size was small, in part due the fact that a number of young adults were still completing their education at the time of the follow-up data collection; they may have been completing advanced degrees often required for prestigious, male-typed occupations in science, medical, or legal professions. Second, parents’ attitudes and work and family lives were treated as static. Because they may change over time (Hynes & Clarkberg, 2005), future studies should examine longitudinal trajectories of attitudes and behaviors across childhood and adolescence in order to better understand how changes in parents’ characteristics may be linked with their children’s occupational attainment and/or when during development parents’ characteristics and activities have their strongest impact. Third, future research is needed with diverse samples that vary in race/ethnicity and family structure to determine the generalizability of our results. Our sample was almost exclusively White, and all youth came from two-parent families. Finally, our study did not examine the possible mechanisms through which early experiences affect later occupational attainment. Such mediating processes might include children’s developing values, interests, school achievement profiles and gender attitudes, which would provide a more thorough examination of the EVT (Wigfield & Eccles, 2000).

Conclusions

The results of this study suggest that childhood family socialization experiences contribute to the gendered segregation of the labor market, providing support for social learning theory and the EVT. By using a longitudinal dataset containing information from multiple family members, we found that mothers’ attitudes and parents’ time spent with their children predicted the gender typicality of their occupational attainments 15 years later. The findings suggest that efforts to desegregate labor markets and remain competitive in the global economy may require interventions at early stages in family socialization. Efforts to promote more flexibility in youths’ gender typical choices should consider both mothers and fathers as role models and sources of advice and support in their children’s career development.

Figure 1.

More traditional maternal gender role attitudes in middle childhood predict sons attaining more gender-typed occupations in young adulthood

Note. Less and more traditional maternal gender role attitudes defined as one standard deviation above and below the mean. Simple slopes obtained using multi-level modeling while controlling for all covariates are significantly different from zero, p < .05. Gender typicality was coded as the percent of women in an occupation, but young men’s scores were reverse-coded so that higher scores reflect more gender-typed occupations for both young men and women.

Figure 2.

More time with fathers in middle childhood predicts daughters’ attaining less and sons’ attaining more gender-typed occupations in young adulthood

Note. Less and more time with father defined as one standard deviation above and below the mean, respectively. Simple slopes obtained using multi-level modeling while controlling for all covariates are significantly different from zero, p < .05 level. Gender typicality was coded as the percent of women in an occupation, but young men’s scores were reverse-coded so that higher scores reflected more gender-typed occupations for both young men and women.

Highlights.

Childhood experiences predicted gendered occupational attainment in young adulthood

Sons of mothers with more gendered attitudes acquired more gender-typed occupations

For girls, more childhood time with fathers predicted less gender-typed occupations

For boys, more childhood time with fathers predicted more gender-typed occupations

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by a grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01-HD32336) to Ann C. Crouter and Susan M. McHale, Co-Principal Investigators. The authors would like to thank Drs. David Almeida and Rachel Smith for their helpful comments and suggestions on earlier versions of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Barak A, Feldman S, Noy A. Traditionality of children’s interests as related to their parents’ gender stereotypes and traditionality of occupations. Sex Roles. 1991;24(7–8):511–524. [Google Scholar]

- Baruch GK, Barnett RC. Fathers’ participation in family work and children’s sex-role attitudes. Child Development. 1986;57(5):1210–1223. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1986.tb00449.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beere CA. Gender roles: A handbook of tests and measures. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, Inc; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi SM, Milkie MA, Sayer LC, Robinson JP. Is anyone doing the housework? Trends in the gender division of household labor. Social Forces. 2000;79(1):191–228. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Mortimer JT, Lutfey K, Bradley RH. Theories and processes in life-span socialization. In: Fingerman KL, Berg CA, Smith J, Antonucci TC, editors. Handbook of life-span development. New York, NY: Springer; 2011. pp. 27–55. [Google Scholar]

- Brim OG, Ryff CD, Kessler RC. How healthy are we? A national study of well-being at midlife. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bussey K, Bandura A. Social cognitive theory of gender development and differentiation. Psychological Review. 1999;106(4):676–713. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.106.4.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles M. A world of difference: International trends in women’ A world of differen. Annual Review of Sociology. 2011;37:355–71. [Google Scholar]

- Chhin cS, Bleeker MM, Jacobs JE. Gender-typed occupational choices: The long-term impact on parents’ beliefs and expectations. In: Watt HMG, Eccles JS, editors. Gender and Occupational Outcomes. Washington, D.C: American Psychological Association; 2008. pp. x–x. [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran ME, Courant PN. Sex-role socialization and occupational segregation: An exploratory investigation. Journal of Post Keynesian Economics. 1987;9(3):330–346. [Google Scholar]

- Craig L. Does father care mean fathers share? A comparison of how mothers and fathers in intact families spend time with children. Gender & Society. 2006;20(2):259–281. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch FM, Servis LJ, Payne JD. Paternal participation in child care and its effects on children’s self-esteem and attitudes toward gendered roles. Journal of Family Issues. 2001;22(8):1000–1024. [Google Scholar]

- Duffy RD, Dik BJ. Beyond the self: External influences in the career development process. The Career Development Quarterly. 2009;58(1):29–43. [Google Scholar]

- Fiebig JN, Beauregard E. Longitudinal change and maternal influence on occupational aspirations of gifted female American and German adolescents. Journal for the Education of the Gifted. 2011;34(1):45–67. [Google Scholar]

- Hegewisch A, Liepmann H, Hayes J, Hartmann H. Separate and not equal? Gender segregation in the labor market and the gender wage gap. 2010 Institute for Women’s Policy Research Briefing Paper IWPR C377, www.iwpr.org.

- Helwig AA. From childhood to adulthood: A 15-year longitudinal career development study. The Career Development Quarterly. 2008;57(1):38–50. [Google Scholar]

- Huston TL, McHale SM, Crouter AC. Changes in the marital relationship during the first year of marriage. In: Gilmour R, Duck S, editors. The emerging field of personal relationships. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1985. pp. 109–132. [Google Scholar]

- Hynes KH, Clarkberg M. Women’s employment patterns during early parenthood: A group-based trajectory analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67(1):222–239. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-2445.2005.00017.x. [Google Scholar]

- Iida M, Shrout PE, Laurenceau J, Bolger N. Using diary methods in psychological research. In APA handbook of research methods in psychology: Foundations, planning, measures, and psychometrics. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs JE, Eccles JS. The impact of mothers’ gender-role stereotypic beliefs on mothers’ and children’s ability perceptions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;63(6):932–944. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.63.6.932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kite ME. Changing times, changing gender roles: Who do we want women and men to be? In: Unger RK, editor. Handbook of the Psychology of Women and Gender. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2001. pp. 215–227. [Google Scholar]

- Kohn ML. Class and conformity: A study in values. 2nd ed. Homewood, IL: Dorsey; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Lam CB, McHale SM. Developmental patterns and parental correlates of youth leisure-time physical activity. Journal of Family Psychology. 2014 doi: 10.1037/fam0000049. advanced publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHale SM, Crouter AC, Tucker CJ. Family context and gender role socialization in middle childhood: Comparing girls to boys and sisters to brothers. Child Development. 1999;70(4):990–1004. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHale SM, Dotterer AM, Kim J, Crouter AC, Booth A. The development of gendered interests and personality qualities from middle childhood through adolescence: A biosocial analysis. Child Development. 2009;80(2):482–495. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01273.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHale SM, Shanahan L, Updegraff KA, Crouter AC, Booth A. Developmental and individual differences in girls’ sex-typed activities in middle childhood and adolescence. Child Development. 2004;75(5):1575–1593. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paquette D. Theorizing the father-child relationship: Mechanisms and developmental outcomes. Human Development. 2004;47(4):193–219. [Google Scholar]

- Porfeli EJ, Hartung PJ, Vondracek FW. Children’s vocational development: A research rationale. The Career Development Quarterly. 2008;57:25–37. [Google Scholar]

- Royston P, Altman DG, Sauerbrei W. Dichotomizing continuous predictors in multiple regression: A bad idea. Statistics in Medicine. 2006;25(1):127–141. doi: 10.1002/sim.2331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu S, Mortimer JT. The “occupational linkage hypothesis” applied to occupational value formation in adolescence. In: Mortimer JT, Finch MD, editors. Adolescents, work, and family: An intergenerational developmental analysis. Vol. 6. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1996. pp. 167–190. [Google Scholar]

- Sayer LC, Bianchi SM, Robinson JP. Are parents investing less in children? Trends in mothers’ and fathers’ time with children. Journal of Sociology. 2004;110(1):1–43. [Google Scholar]

- Schuette CT, Ponton MK, Charlton ML. Middle school children’s career aspirations: Relationship to adult occupations and gender. The Career Development Quarterly. 2012;60(1):35–46. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-0045.2012.00004.x. [Google Scholar]

- Shen-Miller D, Smiler AP. Men in female-dominated vocations: A Rationale for academic study and introduction to the special issue. Sex Roles. 2015;72:269–276. [Google Scholar]

- Serbin LA, Powlishta KK, Gulko J, Martin CL, Lockheed ME. The development of sex typing in middle childhood. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1993;58(2) i-95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spence JT, Helmreich RL. Masculinity and femininity: Their psychological dimensions, correlates, and antecedents. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Steele J, Barling J. Influence of maternal gender-role beliefs and role satisfaction on daughters’ vocational interests. Sex Roles. 1996;34(9–10):637–648. [Google Scholar]

- Steinmetz S. The contextual challenges of occupational sex segregation. Germany: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Stier H, Yaish M. Occupational segregation and gender inequality in job quality: A multi-level approach. Work, Employment, and Society. 2014;28(2):225–246. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Census 2000 EEO Data Tool. 2000 Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/cgi-bin/broker.

- U.S. Census Bureau. EEO 1r. Detailed census occupation by sex and race/ethnicity for residence geography universe: Civilian labor force 16 years and over. 2010 Retrieved from http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/searchresults.xhtml?refresh=t#none.

- Whiston SC, Keller BK. The influences of the family of origin on career development: A review and analysis. The Counseling Psychologist. 2004;32:493–568. [Google Scholar]

- Wigfield A, Eccles JS. Expectancy-value theory of achievement motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology. 2000;25:68–81. doi: 10.1006/ceps.1999.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]