Abstract

Patient: Female, 63

Final Diagnosis: Drug-induced hyponatremic encephalopathy

Symptoms: Seizures • coma

Medication: Hypertonic 3% saline infusion

Clinical Procedure: —

Specialty: Internal Medicine

Objective:

Unusual clinical course

Background:

Drug-induced hyponatremia characteristically presents with subtle psychomotor symptoms due to its slow onset, which permits compensatory volume adjustment to hypo-osmolality in the central nervous system. Due mainly to the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH), this condition readily resolves following discontinuation of the responsible pharmacological agent. Here, we present an unusual case of life-threatening encephalopathy due to adverse drug-related effects, in which a rapid clinical response facilitated emergent treatment to avert life-threatening acute cerebral edema.

Case Report:

A 63-year-old woman with refractory depression was admitted for inpatient psychiatric care with a normal physical examination and laboratory values, including a serum sodium [Na+] of 144 mEq/L. She had a grand mal seizure and became unresponsive on the fourth day of treatment with the dual serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor [SNRI] duloxetine while being continued on a thiazide-containing diuretic for a hypertensive disorder. Emergent infusion of intravenous hypertonic (3%) saline was initiated after determination of a serum sodium [Na+] of 103 mEq/L with a urine osmolality of 314 mOsm/kg H20 and urine [Na+] of 12 mEq/L. Correction of hyposmolality in accordance with current guidelines resulted in progressive improvement over several days, and she returned to her baseline mental status.

Conclusions:

Seizures with life-threatening hyponatremic encephalopathy in this case likely resulted from co-occurring SIADH and sodium depletion due to duloxetine and hydrochlorothiazide, respectively. A rapid clinical response expedited diagnosis and emergent treatment to reverse life-threatening acute cerebral edema and facilitate a full recovery without neurological complications.

MeSH Keywords: Brain Edema, Hyponatremia, Inappropriate ADH Syndrome

Background

Drug-Induced hyponatremia is a frequent and potentially serious adverse reaction with many psychopharmacological agents, mediated in most cases by the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH) [1–3]. This condition most often leads to subtle psychomotor symptoms due to its slow progression, permitting a compensatory adjustment of intra-cellular volume in the central nervous system. Subtle psycho-motor symptoms and motor imbalance readily resolve after discontinuation of the responsible pharmacological agent [4]. In contrast, rapid onset of hyponatremia may present with life-threatening encephalopathy, which requires emergent infusion of intravenous hypertonic (3%) saline to reverse acute cerebral edema.

We describe herein a patient presenting with seizures 4 days after initiating treatment with the dual serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor [SNRI] duloxetine, with continuation of a thiazide-containing diuretic for a stable hypertensive disorder. Laboratory data determined that SIADH and sodium depletion were collateral underlying causes of this atypical presentation related to duloxetine and hydrochlorothiazide, respectively. A rapid clinical response expedited diagnosis and emergent treatment, averting potentially fatal acute cerebral edema and facilitating a full recovery without neurological complications.

Case Report

A 63-year-old white woman was hospitalized for refractory depression. Physical exam was unremarkable and laboratory values were normal, including a serum sodium [Na+] of 144 meq/L. Treatment was initiated with the SNRI duloxetine and titrated to 40 mg daily over several days while triamterene/hydrochlorothiazide 37.5/25 mg daily was continued for a stable hypertensive disorder. Her daily sodium intake was 5 grams and she had no sign of a thirst disorder. Seizures and unresponsiveness led to an emergent evaluation showing a [Na+] of 103 mEq/L, potassium 3.5 mEq/L, chloride 76 mEq/L, BUN 15 mg/dL, creatinine 0.7 mg/dL, C02 of 16 mEq/L, anion gap 13, lactic acid 4.4 mg/dL, urine osmolality 314 mOsm/kg H20, and urine [Na+] 12 mEq/L. Emergent infusion of intravenous hypertonic (3%) saline according to current clinical guidelines resulted in progressive improvement over several days and a return to her baseline mental status without neurological complications.

Discussion

As the most common electrolyte abnormality in medical practice, recent evidence from meta-analyses indicates that hyponatremia, defined as a reduction in the serum sodium concentration (Na+)<135 mEq/L, is associated with increased morbidity and excess mortality [1,2]. Psychiatric patients are at substantial risk for this adverse event, which may occur with many pharmacologic agents. SIADH is the most common underlying mechanism, accounting for over 80% of cases in psychiatric patients in contrast to less than 30% in general medical practice [3].

SIADH characteristically results in subtle changes in mental status, psychomotor deficits, and motor instability with an increased risk for falling. Optimal treatment of symptomatic hypo-osmolar hyponatremia begins with a high index of suspicion and identification of the underlying cause as determined by simultaneous measurement of serum and urine chemistry (Table 1) [4,5]. Hyponatremia due to SIADH results in less than maximally diluted urine, with an osmolality greater than 100 mOsm/kg H2O and a urine [Na+] greater than 30 mEq/L. Symptoms resolve rapidly after discontinuation of the responsible agent. In contrast, the rapid onset of hyponatremia, as seen in patients with polydipsia, results in maximally diluted urine with a variable sodium content. Sodium depletion results in high urine osmolality with a low urine [Na+] concentration and elevated BUN in the presence of co-occurring dehydration.

Table 1.

Pathophysiologic findings in hypo-osmolar hyponatremia: Differentiation of dilutional versus depletional mechanisms.

| Hypo-osmolar hyponatremia | Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL) | Urine osmolality (mOsm/kg H20) | Urine sodium (mEq/L) | AVP (ng/L) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dilutional | |||||

| • Polydipsia | <15 | <100 | Variable | <1.0 | |

| • SIADH | <15 | >100 | >30 | >1.0 | |

|

| |||||

| Depletional | >15 | >300 | <30 | <30 | |

The underlying mechanism of hypo-osmolar hyponatremia can be assessed according to laboratory criteria. Dilutional hyponatremia due primarily to polydipsia produces a maximally dilute urine with a variable (Na+) and suppression of AVP secretion. Dilutional hyponatremia under conditions of SIADH results in a concentrated urine with a sodium value >30 mEq/L and an inappropriate urinary response to hypo-osmolality. Depletional hyponatremia associated with dehydration [BUN >15 mg/dL] leads to concentrated urine with a sodium value <30 mEq/L and volume-dependent stimulation of AVP secretion. AVP – arginine vasopressin; SIADH – syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion. (Adapted from: Siegel AJ: Is urine concentration a reliable biomarker to guide vaptan usage in psychiatric patients with symptomatic hyponatremia? Psychiatry Res, 2015; 226: 403–4).

Taking laboratory findings into account in this case, the urine osmolality of 314 mOsm/kg H20 indicates that the SIADH was likely related to the SNRI duloxetine, while the urine [Na+] of 12 mEq/L represents sodium depletion likely due to hydrochlorothiazide. The co-occurrence of SIADH and sodium depletion likely accounts for the uncharacteristically severe onset of life-threatening hyponatremic encephalopathy in this case, with a higher degree of clinical severity than has been reported previously with either SNRI-induced SIADH or thiazide-induced hyponatremia alone [6]. Co-administration of pharmacological agents conferring risk for dilutional hyponatremia by various mechanisms should therefore be avoided.

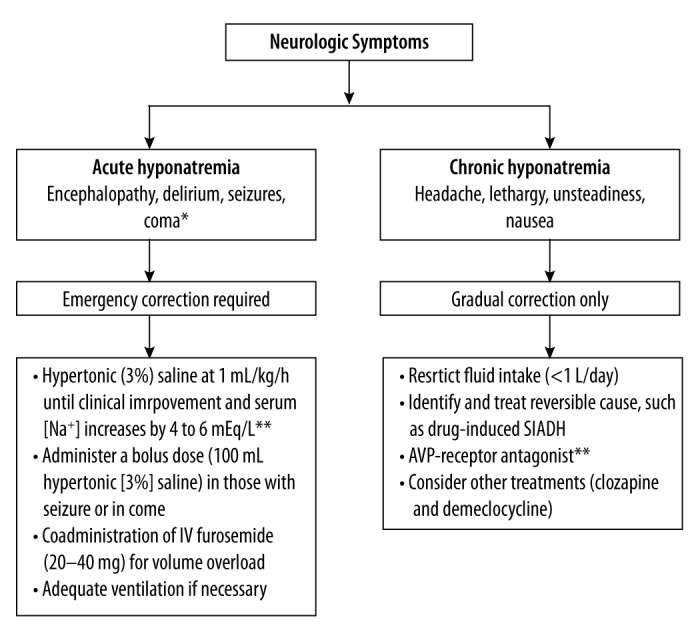

Treatment of symptomatic hyponatremia is guided by the level of clinical severity, as shown in an algorithm based on recent best-practices guidelines (Figure 1) [7,8]. Emergent infusion of intravenous hypertonic (3%) saline is indicated for severe neurological symptoms to rapidly reverse the flow of water in the brain in response to increased blood osmolality. Current guidelines call for a rate of correction with a maximal increase in [Na+] of 8–10 mEq/L in the first 24 hours to avoid the complications of osmotic demyelination syndrome or central pontine myelinolysis [9,10].

Figure 1.

Algorithm for Treatment of Hyponatremia Guided by Clinical Severity 1. Treatment of dilutional hyponatremia in psychiatric patients. * The severity of symptoms is related to the rate of development of the hypo-osmolality; the serum [Na+] at which symptoms appear varies markedly among individuals, although most patients demonstrate symptoms when the serum [Na+] falls below 125 mEq/L. ** The rate of correction of hyponatremia should not exceed a maximum of 10 to 12 mEq/L in 24 hours. Adapted from: Siegel AJ: Hyponatremia in psychiatric patients: update on evaluation and management. Harv Rev Psychiatry, 2008; 16: 13–24.

Treatment with vasopressin receptor blockers as pure aquaretic agents may be indicated with moderate symptoms, as shown to be efficacious and safe for patients with SIADH [11,12]. A summary of current treatment practices based on an international registry showed a greater likelihood of meaningful correction of hyponatremia with these agents compared to alternative therapies [13,14]. The finding of a urine concentration above 219 mOsm/kg has been identified as a potentially reliable biomarker for the efficacy of vaptan usage unless precluded, as in this case, by the degree of clinical severity [15,16].

Conclusions

A rapid clinical response to the abrupt onset of seizures expedited diagnosis and emergent treatment, reversing acute cerebral edema and facilitating a full recovery without neurological complications. Clinicians prescribing pharmacological agents conferring risk for dilutional hyponatremia should maintain a high index of suspicion for the full spectrum of consequent clinical severity.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

None.

References:

- 1.Basu A, Ryder REJ. The syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis is associated with excess long-term mortality: A retrospective cohort analysis. J Clin Pathol. 2014;67(9):802–6. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2014-202243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Corona G, Guiliani C, Parenti G, et al. Moderate hyponatremia is associated with increased risk of mortality: evidence from a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e80451. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lange-Asschenfeldt C, Kojda G, Cordes J, et al. Epidemiology, symptoms and treatment characteristics of hyponatremic psychiatric patients. J Clin Psychopharm. 2013;33:799–805. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e3182a4736f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siegel AJ, Baldessarini RJ, Klepser MB, McDonald JC. Primary and drug-induced disorders of water homeostasis in psychiatric patients: Principles of diagnosis and management. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 1998;6(4):190–200. doi: 10.3109/10673229809000329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siegel AJ. Hyponatremia in psychiatric patients: Update on evaluation and management. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2008;16:13–24. doi: 10.1080/10673220801924308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu BA, Mittman N, Knowles SR, Shear NH. Hyponatremia and the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion with the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: A review of spontaneous reports. CMAJ. 1996;155(5):519–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thompson C, Berl T, Tejedor A, Johannsson G. Differential diagnosis of hyponatrmia. Best Prac Resr Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;26(Suppl.1):s7–15. doi: 10.1016/S1521-690X(12)70003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoon EJ, Bouloux PM, Burst V. Perspectives on the treatment of hyponatraemia secondary to SIADH across Europe. Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;26(Suppl.1):S27–32. doi: 10.1016/S1521-690X(12)70005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verbalis JG, Goldsmith SR, Greenberg, et al. Diagnosis, evaluation and management of hyponatremia: Expert panel recommendations. Am J Med. 2013;126(10 Suppl.1):S1–S42. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spasovski G, Vanholder R, Allolio B, et al. on behalf of the Hyponatremia Guidelines Development Group Clinical practice guideline on diagnosis and treatment of hyponatraemia. European J Endocrinol. 2014;170:G1–47. doi: 10.1530/EJE-13-1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Josiassen RC, Goldman M, Jessani M, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled, multi-center trial of a vasopressin V2-receptor antagonist in patients with schizophrenia and hyponatremia. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64(12):1097–100. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laville M, Burst V, Peri A, Verbalis JG. Hyponatremia secondary to the syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone (SIADH): clinical decision-making in real-life cases. Clin Kidney J. 2013;(Suppl.1):i1–20. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sft113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greenberg A, Verbalis JG, Amin AN, et al. Current treatment practice and outcomes. Report of the hyponatremia registry. Kidney Int. 2015;88(1):167–77. doi: 10.1038/ki.2015.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berl T. Vasopressin Antagonists. N Engl J Med. 2015;327(23):2207–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1403672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Atsariyasing W, Goldman MB. A systematic review of the ability of urine concentration to distinguish antipsychotic – from psychosis-induced hyponatremia. Psychiatry Res. 2014;217(3):129–33. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Siegel AJ. Is Urine concentration a reliable biomarker to guide vaptan usage in psychiatric patients with symptomatic hyponatremia? Psych Research. 2015;226:403–4. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.12.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]