Guidelines recommend that pregnant women be vaccinated against pertussis between gestational weeks 26 and 36. We show that this narrow window can be widened, as optimal neonatal antibody concentrations and expected infant seropositivity rates are elicited between weeks 13 and 33.

Keywords: pertussis, maternal immunization, maternal antibodies, pregnancy, neonates

Abstract

Background. Maternal immunization against pertussis is currently recommended after the 26th gestational week (GW). Data on the optimal timing of maternal immunization are inconsistent.

Methods. We conducted a prospective observational noninferiority study comparing the influence of second-trimester (GW 13–25) vs third-trimester (≥GW 26) tetanus-diphtheria-acellular pertussis (Tdap) immunization in pregnant women who delivered at term. Geometric mean concentrations (GMCs) of cord blood antibodies to recombinant pertussis toxin (PT) and filamentous hemagglutinin (FHA) were assessed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. The primary endpoint were GMCs and expected infant seropositivity rates, defined by birth anti-PT >30 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay units (EU)/mL to confer seropositivity until 3 months of age.

Results. We included 335 women (mean age, 31.0 ± 5.1 years; mean gestational age, 39.3 ± 1.3 GW) previously immunized with Tdap in the second (n = 122) or third (n = 213) trimester. Anti-PT and anti-FHA GMCs were higher following second- vs third-trimester immunization (PT: 57.1 EU/mL [95% confidence interval {CI}, 47.8–68.2] vs 31.1 EU/mL [95% CI, 25.7–37.7], P < .001; FHA: 284.4 EU/mL [95% CI, 241.3–335.2] vs 140.2 EU/mL [95% CI, 115.3–170.3], P < .001). The adjusted GMC ratios after second- vs third-trimester immunization differed significantly (PT: 1.9 [95% CI, 1.4–2.5]; FHA: 2.2 [95% CI, 1.7–3.0], P < .001). Expected infant seropositivity rates reached 80% vs 55% following second- vs third-trimester immunization (adjusted odds ratio, 3.7 [95% CI, 2.1–6.5], P < .001).

Conclusions. Early second-trimester maternal Tdap immunization significantly increased neonatal antibodies. Recommending immunization from the second trimester onward would widen the immunization opportunity window and could improve seroprotection.

Decades after the introduction of pertussis vaccines, infant pertussis-related hospitalizations and deaths persist and have even increased in countries with high immunization rates [1–4]. Indeed, pertussis has the highest disease burden in infants aged <3 months [3, 4]. As pertussis vaccines are licensed for use only after 6 weeks of age and the first infant dose only confers partial protection [5], additional preventive strategies are required for the very young [6]. Efficient cocooning strategies are difficult to implement [7], and neonatal vaccination has limitations [8–10]. In contrast, pertussis antibodies of maternal origin are readily transferred to the fetus [11–13]. For this reason, and in the context of a public health crisis, health authorities recommended the immunization of pregnant women against pertussis [14–16]. These recommendations were issued between 2011 and 2014, prior to the generation of a high level of evidence on the optimal timing of maternal immunization—and the demonstration of its efficacy [17, 18]. In the United States, maternal immunization was first recommended during “late gestation,” after gestational week (GW) 20 [14]. The window was subsequently narrowed to GW 27–36 [15], a strategy also adopted in the United Kingdom [16].

Given the paucity of available data on which to issue evidence-based recommendation, Swiss health authorities recommend maternal immunization in the second or third trimester [19]. We designed a prospective observational noninferiority study with the primary aim of determining whether tetanus-diphtheria-acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccination as early as GW 13–25 elicits noninferior geometric mean concentrations (GMCs) of infant cord blood antibodies against pertussis toxin (PT) and filamentous hemagglutinin (FHA) compared with immunization after GW 25. To maximize our observations' relevance to seroprotection, we quantified antibodies against a genetically inactivated PT whose immunogenicity is closest to that of native PT [20, 21].

METHODS

Study Design and Objectives

This prospective observational noninferiority nonrandomized controlled study was designed to test the noninferiority of antibody transfer following second-trimester (GW 13–25) vs third-trimester (GW ≥26) maternal Tdap immunization by comparing GMCs and expected infant seropositivity rates. Secondary objectives were to define potential differences among populations and the influence of the time interval between maternal immunization and delivery on infant cord GMCs.

The study was funded by the Center for Vaccinology of the University of Geneva and conducted in accordance with International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines. The Ethics Commission of the Canton of Geneva, Switzerland, approved the study protocol (CCER 14-096). All participants provided written informed consent prior to enrollment at the maternity ward of the University Hospital of Geneva.

Study Population

Eligible participants were consenting pregnant women vaccinated with Tdap after GW 13 and delivering after GW 36 at the University Hospitals of Geneva after 15 July 2014. For twin births (n = 7), blood was collected only from the firstborn twin. Exclusion criteria were known or suspected alteration of immune function resulting from immune deficiency or immunosuppressive therapy during the past 3 months, known exposure to pertussis (positive polymerase chain reaction or culture), previous pertussis immunization in the preceding 5 years, and major neonatal malformations. Cord blood samples of 90 neonates of nonvaccinated mothers recruited in a similar study in 2011, prior to maternal Tdap recommendation, were used as negative controls [22].

Data Collection

A sample of umbilical cord blood (3 mL) was collected immediately after birth and transferred to the Laboratory of Vaccinology of the University Hospitals of Geneva. Samples were centrifuged and aliquoted; sera were frozen at −20°C until assessed. All samples were analyzed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as described previously [21, 23], using plates coated with genetically inactivated PT or FHA (BioNet-Asia) [21] to quantify immunoglobulin G (IgG) serum antibodies. The assays were calibrated using World Health Organization international standards (National Institute for Biological Standards and Control [NIBSC] 06/140), and positive (NIBSC 06/142) and negative (Bordetella pertussis ESR120G, Virion-Serion) controls. The lower limit of detection was 1 ELISA unit (EU)/mL, and the quantification thresholds were set at 5 EU/mL.

To identify potential determinants of vaccine responses and antibody transfer, we collected maternal medical and social histories (including employment resulting in exposure to young children), date of Tdap (Boostrix dTpa, GlaxoSmithKline) immunization, gravidity, parity, and maternal and gestational age at delivery. A socioeconomic status (SES) score was calculated as the sum of maternal educational level (from 6 [primary school] to 1 [higher education]) and paternal profession (from 6 [unskilled labor] to 1 [profession after graduate studies]; 0 if unknown) as described elsewhere [24]. Neonatal characteristics included birth weight and height, sex, and health status.

Definition of Expected Infant Seropositivity

The antibody concentration required for seroprotection against pertussis is unknown. Given the postulated critical role of anti-PT antibodies against severe infant pertussis [25], we based our cutoff for expected infant seropositivity on the published anti-PT half-life (36 days) in adults [26], which was confirmed in infants of mothers immunized during pregnancy [12, 27, 28]. We calculated that birth anti-PT concentrations >30 EU/mL would be associated with seropositivity (antibody persistence >5 EU/mL) until at least 3 months of age and defined “expected infant seropositivity” accordingly. In the absence of similar data for anti-FHA antibodies, results were only expressed as GMCs and their 95% confidence interval (CI).

Sample Size and Statistical Analyses

The sample size was calculated to show noninferiority, with a margin of 10%, in expected infant seropositivity rates among women immunized in the second vs the third trimester. Postulating that 90% of term neonates born to women immunized in the third trimester would be seropositive up to 3 months and assuming balanced groups, a 1-sided risk α of 2.5%, and a power of 90%, we initially calculated a necessary sample size of 210 women per group. This sample size exceeded the number of patients required to show noninferiority in the anti-PT GMC ratio (133 women per group, assuming a third-trimester GMC equal to 17.3 [13]). Ultimately, however, the paucity of women immunized in the second trimester led to a final inclusion of 122 women in this group. Given uncertainties on the required minimal sample size and the wish to avoid introducing potential pertussis exposure bias, recruitment was eventually terminated on 30 May 2015. A 95% CI of the GMC ratio above 0.67 determined GMC noninferiority in the second trimester group. Similarly, noninferiority was reached if the 2-sided 95% CI around the difference in expected infant seropositivity rates (second minus third trimester) was entirely above −10%, or equivalently if the 2-sided 95% CI around the odds ratio (OR) was entirely above 0.44.

Descriptive analyses were performed to identify potential differences between the 2 study groups using the Mann–Whitney, Student t, Fisher exact, and χ2 tests. The association between trimester of immunization and the GMCs of anti-PT and anti-FHA were assessed with the base-10 logarithm function (log) and compared between study groups. Linear regression models were used with adjustment for characteristics that were either unbalanced among the 2 groups or could potentially impact maternal vaccine responses to assess associations. As the titers were not normally distributed, they were transformed with the base-10 logarithm function. The regression coefficients were then back-transformed and expressed as ratios of GMCs. The normality of the distribution of residual was visually inspected. In addition to the differences in antibody GMCs, expected infant seropositivity was assessed via logistic regression. The logistic model's goodness of fit was tested using the Hosmer-Lemeshow test.

To assess the influence of the timing of maternal vaccination on birth GMCs and expected infant seropositivity rates, we performed multivariate regression analyses to calculate adjusted GMC ratios/ORs for various intervals of GW at vaccination (GW 13–16, 17–21, 22–25, 26–29, 30–33, 34–36, 37–38, and 39–41). Results are displayed as reverse cumulative distribution curves.

A P value <.05 was considered statistically significant. Stata software version 13 (StataCorp) was used for all statistical analyses.

RESULTS

Study Population

Ultimately, we enrolled 335 pregnant women immunized with Tdap and delivering term newborns between 15 July 2014 and 30 May 2015 (Supplementary Figure 1); 213 of 335 (64%) were immunized during the third trimester and 122 of 335 (36%) during the second. At baseline, the 2 groups differed significantly only with regard to parity and 2 SES scores (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Women and Newborns

| Characteristics | All (n = 335) | Maternal Tdap Immunization in Second Trimester (n = 122) | Maternal Tdap Immunization in Third Trimester (n = 213) | P Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | ||||

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 31.0 (5.1) | 30.3 (5.0) | 31.3 (5.1) | .092 |

| Parity | ||||

| Primiparous | 178 (53%) | 55 (45%) | 123 (58%) | |

| Multiparous | 157 (47%) | 67 (55%) | 90 (42%) | .025* |

| Median (IQR) | 0 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 (1) | |

| Gravidity | ||||

| First | 136 (41%) | 44 (36%) | 92 (43%) | |

| Multiple gestation | 199 (59%) | 78 (64%) | 121 (57%) | .201 |

| Median (IQR) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | |

| Gestational week at immunization | <.001** | |||

| 39–41 | 21 (6%) | 0 (0%) | 21 (10%) | |

| 37–38 | 74 (22%) | 0 (0%) | 74 (35%) | |

| 34–36 | 72 (21%) | 0 (0%) | 72 (34%) | |

| 30–33 | 16 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 16 (7%) | |

| 26–29 | 30 (9%) | 0 (0%) | 30 (14%) | |

| 22–25 | 54 (16%) | 54 (44%) | 0 (0%) | |

| 17–21 | 42 (13%) | 42 (35%) | 0 (0%) | |

| 13–16 | 26 (8%) | 26 (21%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Maternal history during pregnancy | ||||

| Smoking before pregnancy | 62 (19%) | 19 (16%) | 43 (20%) | .295 |

| Smoking during pregnancy | 40 (12%) | 13 (11%) | 27 (13%) | .865 |

| Alcohol use before pregnancy | 6 (2%) | 3 (2%) | 3 (1%) | .672 |

| Alcohol use during pregnancy | 2 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (1%) | .400 |

| Steroid use | 2 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (0%) | 1.000 |

| NSAID use | 1 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0%) | 1.000 |

| Drug use before pregnancy | 3 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 1.000 |

| Drug use during pregnancy | 1 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0%) | 1.000 |

| SES and profession | ||||

| SES score, mean (95% CI) | 6.5 (6.2–6.9) | 7.0 (6.5–7.6) | 6.3 (5.8–6.7) | .038* |

| Maternal education level, mean (95% CI) | 3.2 (3.0–3.4) | 3.5 (3.2–3.8) | 3.0 (2.8–3.3) | .015* |

| Paternal profession, mean (95% CI) | 3.3 (3.1–3.5) | 3.5 (3.2–3.8) | 3.2 (3.0–3.5) | .213 |

| Maternal employment with child contact | 36 (11%) | 11 (9%) | 25 (12%) | .44 |

| Newborns | ||||

| Gestational age, wk (SD) | 39.3 (1.3) | 39.1 (1.3) | 39.4 (1.2) | .06 |

| Mean birth weight, g (SD) | 3344 (453) | 3343 (482) | 3345 (436) | .97 |

| Mean height, cm (SD) | 50.3 (2.3) | 50.3 (2.5) | 50.3 (2.1) | .96 |

| Male sex | 189 (56%) | 69 (57%) | 120 (56%) | .969 |

| Multiple gestations | 7 (2%) | 5 (4%) | 2 (1%) | .104 |

| Intrauterine growth retardation | 41 (12%) | 14 (12%) | 27 (13%) | .747 |

| Interval between vaccination and delivery | <.001** | |||

| <15 d | 68 (20%) | 0 (0%) | 68 (32%) | |

| 15–30 d | 75 (22%) | 0 (0%) | 75 (35%) | |

| 31–60 d | 33 (10%) | 0 (0%) | 33 (16%) | |

| 61–90 d | 35 (11%) | 7 (6%) | 28 (13%) | |

| 91–120 d | 57 (17%) | 48 (39%) | 9 (4%) | |

| 121–150 d | 30 (9%) | 30 (25%) | 0 (0%) | |

| ≥151 d | 37 (11%) | 37 (30%) | 0 (0%) | |

Data are presented as No. (%) unless otherwise specified.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; IQR, interquartile range; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; SD, standard deviation; SES, socioeconomic status; Tdap, tetanus-diphtheria-acellular pertussis.

a The t test (normal distribution) or Mann–Whitney test for comparison between means; χ2 test or Fisher exact test for comparisons between proportions. Distinct denominators among SES variables reflect missing data in 3 subcategories.

*P < .05 and **P < .001.

Anti-PT and Anti-FHA Antibody Concentrations

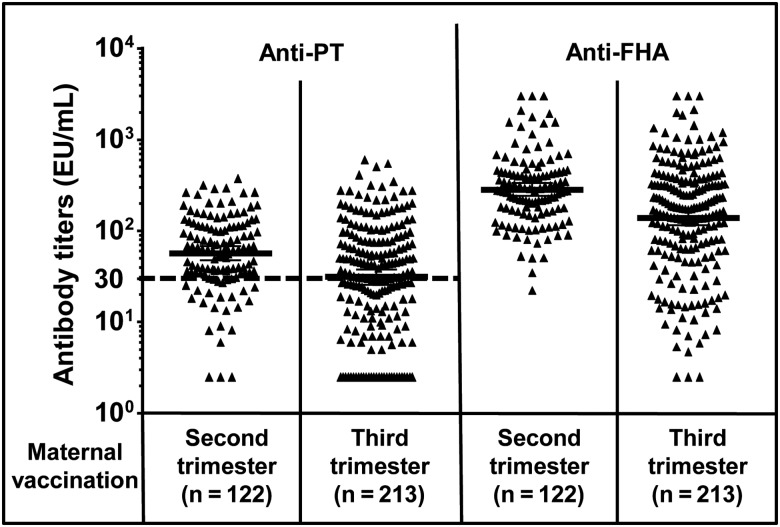

Birth anti-PT GMCs in cord blood were significantly higher following second- vs third-trimester immunization (57.1 EU/mL [95% CI, 47.8–68.2] vs 31.1 EU/mL [95% CI, 25.7–37.7], respectively; P < .001) and anti-FHA (284.4 EU/mL [95% CI, 241.3–335.2] vs 140.2 EU/mL [95% CI, 115.3–170.3], respectively; P < .001; Figure 1). The nonadjusted GMC ratios of anti-PT (1.8 [95% CI, 1.4–2.4]) and anti-FHA (2.0 [95% CI, 1.5–2.7]) were also largely above the set noninferiority cutoff of 0.67. Because participating women were not randomized, we adjusted the GMC ratios for characteristics unbalanced between study groups (age, gestational age, parity, SES score) and potentially impacting maternal vaccine responses (eg, employment-related contact with children). Calculating the adjusted GMC ratios for anti-PT (1.9 [95% CI, 1.4–2.5]) and anti-FHA (2.2 [95% CI, 1.7–3.0]) confirmed that GMCs were significantly higher following second-trimester immunization (P < .001; Figure 1 and Table 2).

Figure 1.

Anti–pertussis toxin (PT) and anti–filamentous hemagglutinin (FHA) cord blood antibody concentrations by trimester of maternal immunization. Individual anti-PT and anti-FHA antibody concentrations in newborns of mothers vaccinated with tetanus-diphtheria-acellular pertussis during the second or the third trimester; each point corresponds to 1 patient. Geometric mean concentrations and 95% confidence intervals are indicated. The dotted line indicates the cutoff for expected infant seropositivity (anti-PT = 30 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay units [EU]/mL).

Table 2.

Multivariate Regression Analysis of Determinants of Cord-Blood Antibody Concentrations and Expected Infant Seropositivity Rates

| Determinants | Anti-PT GMC |

Anti-FHA GMC |

Infant Seropositivity Ratesa |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | OR (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Trimesterb | 1.9 (1.4–2.5) | <.001* | 2.2 (1.7–3.0) | <.001* | 3.7 (2.2–6.5) | <.001* |

| Age (per 5 y) | 0.9 (.8–1.0) | .05 | 1.0 (.9–1.1) | .688 | 0.9 (.7–1.1) | .195 |

| Gestational age at birth (per week) | 1.3 (1.2–1.5) | <.001* | 1.3 (1.2–1.5) | <.001* | 1.5 (1.2–1.8) | <.001* |

| Parityc | 1.1 (.9–1.5) | .408 | 1.0 (.7–1.3) | .743 | 1.0 (.6–1.7) | .973 |

| Maternal employment with child contact | 0.8 (.5–1.3) | .419 | 1.0 (.6–1.5) | .839 | 0.8 (.4–1.8) | .612 |

| SES score | 1.0 (1.0–1.1) | .964 | 1.0 (1.0–1.1) | .950 | 1.0 (.9–1.1) | .955 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; EU, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay units; FHA, filamentous hemagglutinin; GMC, geometric mean concentration; OR, odds ratio; PT, pertussis toxin; SES, socioeconomic status [24].

a Infant seropositivity defined as birth anti-PT >30 EU/mL.

b Third trimester as reference.

c Primiparous as reference.

*P < .001.

Restricting the third trimester to the currently recommended GW 26–36 yielded similar results (anti-PT GMCs: second trimester 57.1 EU/mL [95% CI, 47.8–69.2], third trimester 44.4 EU/mL [95% CI, 35.3–55.9], P < .001; anti-FHA GMCs: second trimester 284.4 EU/mL [95% CI, 241.3–335.2], third trimester 237.6 EU/mL [95% CI, 188.0–300.3], P < .001). The lower 95% CIs of adjusted GMC ratios were >1 (anti-PT: 1.2 [95% CI, .9–1.6]); (anti-FHA: 1.3 [95% CI, 1.04–1.7]), reaching statistical significance for superiority for anti-FHA.

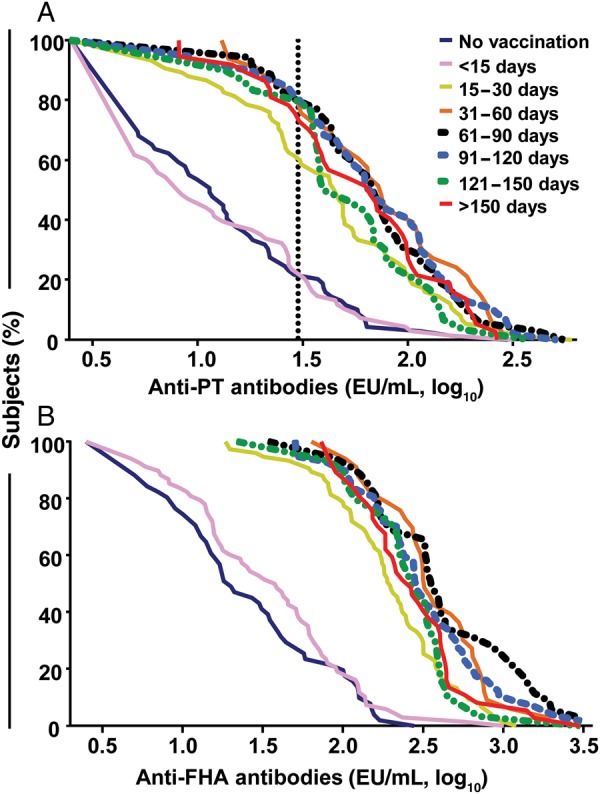

Influence of the Time Interval Between Vaccination and Delivery

We next assessed the influence of the interval between vaccination and delivery. Cord sera of 90 offspring born to nonimmunized women [22] were used as controls for the 68 newborns whose mothers were immunized <2 weeks prior to delivery. Valid ELISA results were obtained for 69 (anti-PT) and 51 (anti-FHA) samples. Cord blood anti-PT GMCs (9.9 EU/mL [95% CI, 7.2–13.6] vs 11.1 EU/mL [95% CI, 8.3–15.0]) were similar in infants whose mothers were immunized <2 weeks prior to delivery or not immunized, respectively (Figure 2A), a finding consistent with the known lack of protection following vaccination within 14 days of delivery. The same applied to anti-FHA (GMC 33.3 EU/mL [95% CI, 24.7–45.1] vs 23.4 EU/mL [95% CI, 16.3–33.4] in controls; Figure 2B). The 68 neonates born <15 days after maternal immunization were thus used as surrogates for a nonvaccinated reference group in multivariate analyses. Antibody concentrations markedly increased with intervals >14 days, reaching optimal GMCs (Figure 2) with intervals between 30 and 120 days. Unexpectedly high GMCs were observed in neonates of 37 women immunized >150 days prior to delivery.

Figure 2.

Distribution of anti–pertussis toxin (PT) and anti–filamentous hemagglutinin (FHA) infant cord blood antibody concentrations according to time between maternal tetanus-diphtheria-acellular pertussis (Tdap) immunization and delivery. The curves represent the distribution of individual anti-PT (A) and anti-FHA (B) antibody concentration (log10) at various time intervals between maternal Tdap immunization and delivery. The vertical line indicates the cutoff for expected infant seropositivity (anti-PT ≥30 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay units [EU]/mL).

To further assess the impact of the timing of maternal immunization, we calculated neonatal GMCs by gestational age at maternal Tdap immunization. Similar neonatal anti-PT and anti-FHA GMCs were observed following immunization between GW 13 and 33 (Table 3). Calculating the expected waning of anti-PT antibodies confirmed that immunization between GW 13 and 33 should confer seropositivity (anti-PT >5 EU/mL) to all infants up to 3 months of age.

Table 3.

Influence of Gestational Age at Maternal Tetanus-diphtheria-acellular pertussis Immunization on Neonatal Geometric Mean Concentrations and Expected Infant Seropositivity Rates

| Gestational Week at Maternal Vaccination | No. (%) | Anti-PT GMC (95% CI) | Anti-FHA GMC (95% CI) | Infant Seropositivitya, No. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 39–41 | 21 (6) | 9.0 (5.0–16.2) | 31.0 (16.9–56.6) | 4 (19) |

| 37–38 | 74 (22) | 25.1 (17.9–35.3) | 92.7 (69.0–124.7) | 37 (50) |

| 34–36 | 72 (22) | 32.7 (24.1–44.3) | 173.0 (126.5–236.6) | 40 (56) |

| 30–33 | 16 (5) | 74.9 (38.3–146.4) | 417.3 (232.7–748.4) | 12 (75) |

| 26–29 | 30 (9) | 70.3 (49.0–100.8) | 376.8 (257.0–552.7) | 23 (77) |

| 22–25 | 54 (16) | 68.3 (52.8–88.3) | 291.8 (222.8–382.2) | 45 (83) |

| 17–21 | 42 (13) | 53.1 (37.2–75.7) | 267.3 (205.4–347.9) | 32 (76) |

| 13–16 | 26 (8) | 44.2 (32.2–60.7) | 297.9 (206.7–429.4) | 20 (77) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; EU, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay units; FHA, filamentous hemagglutinin; GMC, geometric mean concentration; PT, pertussis toxin.

a Infant seropositivity defined as birth anti-PT >30 EU/mL.

Univariate (Supplementary Table 1) and multivariate (Table 4) analyses assessed the impact of various factors on antipertussis immunity; gestational age at maternal Tdap immunization was the only significant predictor identified.

Table 4.

Multivariate Regression Analysis of the Impact of Various Factors on Antibody Concentrations and Expected Infant Seropositivity Rates

| Determinants |

Anti-PT GMC |

Anti-FHA GMC |

Infant Seropositivitya |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | OR (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Gestational week at maternal Tdap immunization | |||||||

| 39–41 | 21 (6) | Reference category | |||||

| 37–38 | 74 (22) | 3.8 (2.2–6.7) | <.001*** | 4.2 (2.5–7.1) | <.001*** | 6.9 (2.0–23.2) | .002** |

| 34–36 | 72 (22) | 5.7 (3.2–10.1) | <.001*** | 8.8 (5.2–15.1) | <.001*** | 10.9 (3.1–38.0) | <.001*** |

| 30–33 | 16 (5) | 9.9 (4.7–20.9) | <.001*** | 15.7 (7.8–31.6) | <.001*** | 17.3 (3.4–86.9) | .001** |

| 26–29 | 30 (9) | 11.3 (5.9–21.9) | <.001*** | 18.4 (10.0–34.0) | <.001*** | 27.4 (6.4–116.9) | <.001*** |

| 22–25 | 54 (16) | 10.0 (5.5–18.0) | <.001*** | 13.2 (7.6–22.9) | <.001*** | 43.2 (10.8–173.1) | <.001*** |

| 17–21 | 42 (13) | 8.7 (4.7–16.3) | <.001*** | 14.8 (8.2–26.5) | <.001*** | 27.5 (6.9–110.7) | <.001*** |

| 13–16 | 26 (8) | 7.7 (3.9–15.1) | <.001*** | 16.3 (8.7–30.5) | <.001*** | 32.4 (7.2–145.7) | <.001*** |

| Gestational age at birth (per week) | 335 (100) | 1.4 (1.3–1.5) | <.001*** | 1.5 (1.3–1.6) | <.001*** | 1.7 (1.3–2.1) | <.001*** |

| Maternal age (per 5 y) | 335 (100) | 0.9 (.8–.99) | .028* | 0.96 (.85–1.1) | .506 | 0.8 (.7–1.1) | .187 |

| Parity | |||||||

| Primiparous | 178 (53) | Reference category | |||||

| Multiparous | 157 (47) | 1.2 (.9–1.5) | .281 | 1.0 (.8–1.3) | .955 | 1.0 (.7–1.1) | .944 |

| Professional contact with children | 36 (11) | 0.7 (.5–1.1) | .113 | 0.8 (.5–1.2) | .234 | 0.7 (.3–1.5) | .319 |

| SES score | 0.99 (.95–1.0) | .667 | 1.0 (.95–1.0) | .671 | 1.0 (.9–1.1) | .869 | |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; EU, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay units; FHA, filamentous hemagglutinin; GMC, geometric mean concentration; OR, odds ratio; PT, pertussis toxin; SES, socioeconomic status [24]; Tdap, tetanus-diphtheria-acellular pertussis.

a Infant seropositivity defined as birth anti-PT >30 EU/mL.

*P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

Expected Infant Seropositivity Rates

Seropositivity was frequent: Anti-PT antibodies were >5 EU/mL in 119 of 122 (98%) vs 182 of 213 (86%) neonates after second- vs third-trimester immunization, respectively (P < .001; data not shown). The seroprotection rate reached 80% (97/122) and 55% (116/213) (P < .001) after second- and third-trimester immunization, respectively (Figure 1). This 25% [95% CI, 14.8%–35.6%] difference in seroprotection rates not only reached noninferiority criteria for second-trimester immunization but demonstrated superiority (P < .001). The unadjusted OR for neonatal seroprotection after second- vs third-trimester immunization was 3.2 ([95% CI, 2.0–5.4]; P < .001), similar to the adjusted OR (3.7 [95% CI, 2.2–6.5]), thus further supporting a conclusion favoring second-trimester immunization (P < .001). The ORs for other factors are shown in Table 2.

As our cutoff for expected infant seropositivity was extrapolated, we conducted sensitivity analyses by modifying the limit of cord blood anti-PT antibodies to >20 EU/mL and >10 EU/mL. This did not eliminate the superiority of second-trimester immunization (>20 EU/mL: 107/122 [88%] vs 145/213 [68%], P < .001; >10 EU/mL: 115/122 [94%] vs 165/213 [78%], P < .001). Similarly, restricting the third trimester to the currently recommended GW 26–36, we found expected infant seropositivity rates of 75 of 118 (64%) vs 97 of 122 (80%) after second-trimester immunization (P = .006). The adjusted OR was 2.3 ([95% CI, 1.2–4.3]; P = .011).

DISCUSSION

This study revisits the important question of the optimal timing of maternal pertussis immunization for antibody transfer. Designed as a noninferiority study given the expectation of lower GMCs and expected infant seropositivity rates following second-trimester maternal Tdap immunization [13], its results indicate, rather, the superiority of earlier immunization: GMCs and expected infant seropositivity rates were significantly higher following second- vs third-trimester immunization, even after adjustments.

Defining the optimal timing for maternal immunization is critical: The half-life of antipertussis antibodies is short [26] and seroprotection should be extended as long as possible [5]. It is well established that infants may be protected against pertussis via the transplacental transfer of maternal antibodies [17, 18, 29]. Anti-PT antibodies are considered crucial for protection against severe infant pertussis [25], although titers required for protection are undefined. These antibodies rapidly wane after delivery [12, 27, 28]; strategies are thus needed to maximize their maternofetal transfer. Antibody transfer [30] occurs during the second and third trimester [31], resulting in a higher neonatal/maternal GMC ratio at term (1.5–1.7) [32, 33] than at GW 32–33 [34, 35]. Early observational studies suggested that higher birth titers were elicited by immunizing after GW 25, leading to the recommendation of the GW 26–36 window [15, 16]. Recently, a small observational study including 60 neonates reported higher anti-PT and anti-FHA antibody concentrations following immunization at GW 27–30 compared with beyond GW 31 [36]. However, the observation of higher infant anti-PT and anti-FHA concentrations following immunization at GW 13–25 rather than after GW 26 was entirely unexpected.

The finding that immunization in early pregnancy results in higher cord blood GMCs is in apparent contradiction with the observed progressive increase of IgG transfer efficiency in late gestation [30–35]. It suggests that a prolonged maternofetal transfer cumulatively results in a higher amount of transferred IgG than a shorter exposure at the time of peak transfer efficacy (GW 32–33). Although unexpected, this is in accordance with the active, saturable nature of FcRn-mediated transfer [30]. Despite antibody detection with a genetically detoxified PT whose immunogenicity is closest to that of native PT [20, 21], seroprotection rates are lower than the first reported vaccine effectiveness [17, 18]. Whether this reflects a contribution of indirect protection remains to be defined.

This study has some limitations. First, our study was observational rather than randomized, which may have confounding effects; distinct socioeconomic factors were included in the multivariate analysis to control for potential confounders. Nevertheless, this does not exclude unidentified differences. Second, antibody persistence was not measured in infants but was calculated. Thus, the true magnitude and persistence of antibody titers may differ. All women were immunized with a single Tdap vaccine, which increases homogeneity but prevents us from formally extending our conclusions to other formulations. However, this study has unique strengths: Its unprecedented size was sufficient to enable sensitivity and multivariate analyses, which in turn allowed for a robust finding of superiority despite its noninferiority trial design [37, 38].

Extending the immunization opportunity window from GW 13 to GW 33 would reduce missed immunization opportunities in many settings and minimize the large proportion of women delivering within only a few weeks after immunization—too early for sufficient antibody transfer. It may even allow preterm infants to benefit from maternal immunization. Whether maternal Tdap should be preferably recommended at GW 13–25 rather than after GW 26 should now be evaluated through randomized controlled trials. In the meantime, we recommend extending the window of maternal immunization to include the second trimester of gestation.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at http://cid.oxfordjournals.org. Consisting of data provided by the author to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the author, so questions or comments should be addressed to the author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We thank all the women who participated in the study and the midwives who performed repeated blood sampling. We also thank Gianna Cadau, Paolo Valenti, and Stéphane Grillet for excellent technical assistance; Corinne Oberson and Suzanne Duperret-Vonlanthen for excellent administrative support; and Angela Huttner for her outstanding editorial assistance.

Financial support. This work was supported by the Center for Vaccinology and Neonatal Immunology, University of Geneva, Switzerland.

Potential conflicts of interest. C.-A. S. has received grant support for preclinical and clinical studies from several vaccine manufacturers. J. P. is the co-founder and chief scientific officer of BioNet-Asia, and has filed a patent for a recombinant Bordetella pertussis strain. All other authors report no potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Jakinovich A, Sood SK. Pertussis: still a cause of death, seven decades into vaccination. Curr Opin Pediatr 2014; 26:597–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winter K, Harriman K, Zipprich J et al. California pertussis epidemic, 2010. J Pediatr 2012; 161:1091–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Health Protection Agency. Confirmed pertussis in England and Wales: data to end-December 2012. Health Protection Report, 2013; 7. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pertussis outbreak trends. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/pertussis/outbreaks/trends.html Accessed 1 November 2015.

- 5.Tiwari TS, Baughman AL, Clark TA. First pertussis vaccine dose and prevention of infant mortality. Pediatrics 2015; 135:990–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forsyth K, Plotkin S, Tan T, Wirsing von Konig CH. Strategies to decrease pertussis transmission to infants. Pediatrics 2015; 135:e1475–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Urwyler P, Heininger U. Protecting newborns from pertussis—the challenge of complete cocooning. BMC Infect Dis 2014; 14:397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Halasa NB, O'Shea A, Shi JR, LaFleur BJ, Edwards KM. Poor immune responses to a birth dose of diphtheria, tetanus, and acellular pertussis vaccine. J Pediatr 2008; 153:327–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knuf M, Schmitt HJ, Jacquet JM et al. Booster vaccination after neonatal priming with acellular pertussis vaccine. J Pediatr 2010; 156:675–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knuf M, Schmitt HJ, Wolter J et al. Neonatal vaccination with an acellular pertussis vaccine accelerates the acquisition of pertussis antibodies in infants. J Pediatr 2008; 152:655–60, 660.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gall SA, Myers J, Pichichero M. Maternal immunization with tetanus-diphtheria-pertussis vaccine: effect on maternal and neonatal serum antibody levels. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011; 204:334.e1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hardy-Fairbanks AJ, Pan SJ, Decker MD et al. Immune responses in infants whose mothers received Tdap vaccine during pregnancy. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2013; 32:1257–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Healy CM, Rench MA, Baker CJ. Importance of timing of maternal combined tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) immunization and protection of young infants. Clin Infect Dis 2013; 56:539–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated recommendations for use of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid and acellular pertussis vaccine (Tdap) in pregnant women and persons who have or anticipate having close contact with an infant aged <12 months. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2011; 60:1424–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated recommendations for use of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis vaccine (Tdap) in pregnant women—Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2013; 62:131–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.UK Department of Health. Pregnant women to be offered whooping cough vaccination. Available at: http://www.dh.gov.uk/health/2012/09/whooping-cough/ Accessed 1 November 2015.

- 17.Amirthalingam G, Andrews N, Campbell H et al. Effectiveness of maternal pertussis vaccination in England: an observational study. Lancet 2014; 384:1521–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dabrera G, Amirthalingam G, Andrews N et al. A case-control study to estimate the effectiveness of maternal pertussis vaccination in protecting newborn infants in England and Wales, 2012-2013. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 60:333–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Office Fédéral de la Santé Publique. Adaptation des recommandations de vaccination contre la coqueluche: pour les adolescents, les nourrissons fréquentant une structure d'accueil collectif et les femmes enceintes. Bull OFSP 2013; 9:118–23. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seubert A, D'Oro U, Scarselli M, Pizza M. Genetically detoxified pertussis toxin (PT-9K/129G): implications for immunization and vaccines. Expert Rev Vaccines 2014; 13:1191–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buasri W, Impoolsup A, Boonchird C et al. Construction of Bordetella pertussis strains with enhanced production of genetically-inactivated pertussis toxin and pertactin by unmarked allelic exchange. BMC Microbiol 2012; 12:61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rohner GB, Meier S, Bel M et al. Influenza vaccination given at least 2 weeks before delivery to pregnant women facilitates transmission of seroprotective influenza-specific antibodies to the newborn. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2013; 32:1374–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roduit C, Bozzotti P, Mielcarek N et al. Immunogenicity and protective efficacy of neonatal vaccination against Bordetella pertussis in a murine model: evidence for early control of pertussis. Infect Immun 2002; 70:3521–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Largo RH, Pfister D, Molinari L, Kundu S, Lipp A, Duc G. Significance of prenatal, perinatal and postnatal factors in the development of AGA preterm infants at five to seven years. Dev Med Child Neurol 1989; 31:440–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cherry JD, Gornbein J, Heininger U, Stehr K. A search for serologic correlates of immunity to Bordetella pertussis cough illnesses. Vaccine 1998; 16:1901–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Savage J, Decker MD, Edwards KM, Sell SH, Karzon DT. Natural history of pertussis antibody in the infant and effect on vaccine response. J Infect Dis 1990; 161:487–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leuridan E, Hens N, Peeters N, de Witte L, Van der Meeren O, Van Damme P. Effect of a prepregnancy pertussis booster dose on maternal antibody titers in young infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2011; 30:608–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Munoz FM, Bond NH, Maccato M et al. Safety and immunogenicity of tetanus diphtheria and acellular pertussis (Tdap) immunization during pregnancy in mothers and infants: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2014; 311:1760–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heininger U, Riffelmann M, Bar G, Rudin C, von Konig CH. The protective role of maternally derived antibodies against Bordetella pertussis in young infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2013; 32:695–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Firan M, Bawdon R, Radu C et al. The MHC class I-related receptor, FcRn, plays an essential role in the maternofetal transfer of gamma-globulin in humans. Int Immunol 2001; 13:993–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ercan TE, Sonmez C, Vural M, Erginoz E, Torunoglu MA, Perk Y. Seroprevalance of pertussis antibodies in maternal and cord blood of preterm and term infants. Vaccine 2013; 31:4172–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Healy CM, Munoz FM, Rench MA, Halasa NB, Edwards KM, Baker CJ. Prevalence of pertussis antibodies in maternal delivery, cord, and infant serum. J Infect Dis 2004; 190:335–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Palmeira P, Quinello C, Silveira-Lessa AL, Zago CA, Carneiro-Sampaio M. IgG placental transfer in healthy and pathological pregnancies. Clin Dev Immunol 2012; 2012:985646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van den Berg JP, Westerbeek EA, Berbers GA, van Gageldonk PG, van der Klis FR, van Elburg RM. Transplacental transport of IgG antibodies specific for pertussis, diphtheria, tetanus, Haemophilus influenzae type b, and Neisseria meningitidis serogroup C is lower in preterm compared with term infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2010; 29:801–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heininger U, Riffelmann M, Leineweber B, Wirsing von Koenig CH. Maternally derived antibodies against Bordetella pertussis antigens pertussis toxin and filamentous hemagglutinin in preterm and full term newborns. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2009; 28:443–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abu Raya B, Srugo I, Kessel A et al. The effect of timing of maternal tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) immunization during pregnancy on newborn pertussis antibody levels—a prospective study. Vaccine 2014; 32:5787–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Murray GD. Switching between superiority and non-inferiority. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2001; 52:219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for industry—non-inferiority clinical trials. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/ucm/groups/fdagov-public/@fdagov-drugs-gen/documents/document/ucm202140.pdf Accessed 1 November 2015.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.