Abstract

Objectives

Fatigue and other treatment-related symptoms (e.g., sleep disturbance) are critical targets for improving quality of life in patients undergoing chemotherapy. Yoga may reduce the burden of such symptoms. This study investigated the feasibility of conducting a randomized controlled study of a brief yoga intervention during chemotherapy for colorectal cancer.

Design

We randomized adults with colorectal cancer to a brief Yoga Skills Training (YST) or an attention control (AC; empathic attention and recorded education).

Setting

The interventions and assessments were implemented individually in the clinic while patients were in the chair receiving chemotherapy.

Interventions

Both interventions consisted of three sessions and recommended home practice.

Main Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was feasibility (accrual, retention, adherence, data collection). Self-reported outcomes (i.e., fatigue, sleep disturbance, quality of life) and inflammatory biomarkers were also described to inform future studies.

Results

Of 52 patients initially identified, 28 were approached, and 15 enrolled (age Mean=57.5 years; 80% White; 60% Male). Reasons for declining participation were: not interested (n=6), did not perceive a need (n=2), and other (n=5). Two participants were lost to follow-up in each group due to treatment changes. Thus, 75% of participants were retained in the YST and 71% in the AC arm. Participants retained in the study adhered to 97% of the in-person intervention sessions and completed all questionnaires.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated the feasibility of conducting a larger randomized controlled trial to assess YST among patients receiving chemotherapy for colorectal cancer. Data collected and challenges encountered will inform future research.

Keywords: yoga, cancer, chemotherapy, fatigue, sleep disturbance, quality of life

1. Introduction

Fatigue and sleep disturbance are symptoms often experienced by patients receiving chemotherapy for colorectal cancer (CRC). Based on the biobehavioral conceptual framework and research data, fatigue and sleep disturbance co-occur because of shared underlying mechanisms including inflammation [1–3]. Treating fatigue and sleep disturbances may improve the quality of life of patients during chemotherapy [4]. Yet, there are few behavioral interventions designed for CRC patients that aim to proactively improve fatigue and sleep disturbances during treatment.

This study aimed to establish the feasibility of conducting a randomized controlled trial of a Yoga Skills Training (YST) among patients receiving chemotherapy for colorectal cancer. Research supports that yoga is a promising intervention for reducing fatigue and sleep disturbances when implemented as group classes [5, 6, 7]. Preliminary evidence also supports that yoga reduces inflammation [8]. However, barriers limit patients’ participation in group classes such as scheduling or feeling too sick to attend [7, 9]. The proposed YST was designed to lessen these barriers by integrating yoga into the clinic during patients’ visits for chemotherapy. We indicated a priori that a retention rate of 65% would support feasibility for a larger trial.

2. Methods

2.1 Participants

We recruited adults at the Comprehensive Cancer Center of Wake Forest University who were within 2 weeks of initiating a new course of chemotherapy for CRC and willing and able to provide informed consent in English (June 2011–January 2013; ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01590147). Ethical approval was obtained from this University’s local institutional review board (IRB00016716). Enrolled participants were randomized using a computer generated table. Allocation was concealed until participants were assigned (1:1) to YST or an attention control (AC). Both interventions consisted of three fifteen-minute sessions delivered in-person once every two weeks while patients sat in a chair during chemotherapy treatments with recommended home practice.

2.2 Interventions

The three in-person YST sessions were designed to teach the same set of skills: a) awareness meditation; b) movement; c) breathing and relaxation. Patients were given an audio recording of a 15-minute YST session and asked to practice four times per week at home (A.1 Audio Recording of the YST by Lynn Felder, RYT). The YST was informed by the Principal Investigator’s training in adapting yoga for people with cancer (http://www.yogaforpeoplewithcancer.com/) and to the clinical setting (http://www.urbanzen.org/uzit/). All movements were taught while patients were seated during chemotherapy.

The AC sessions included empathic attention to account for nonspecific effects of the YST. An interventionist allowed patients to direct the conversation and provided supportive comments. Additionally, patients were given audio recordings of freely available podcasts related to coping with cancer similar in length to the suggested YST home practice time (Podcasts selected from: http://www.cancercare.org/connect_workshops#past_workshops).

2.3 Measures

Rates of accrual, adherence to the interventions (in person attendance, length of practice, home practice [yes/no]), completion of questionnaires, and satisfaction with the interventions (0 not at all to 4 very much) were documented to assess feasibility. Patient-reported outcomes and inflammation were also assessed during clinic visits for chemotherapy at baseline (week 0) and post-intervention (week 8).

Patient-reported Outcomes

The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Fatigue subscale assessed fatigue [10], the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System–Sleep Disturbance Short Form 4a assessed sleep quality [11], and The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Colorectal assessed quality of life [12]. Higher scores indicate lower fatigue, more sleep disturbance and a better quality of life.

Inflammation

Inflammatory cytokines (Interleukin 6, Interleukin 1 receptor agonist, soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor 1, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and C-reactive protein) were collected via plasma samples along with routine blood draws prior to chemotherapy.

Patients also provided demographic information and their medical charts were reviewed.

2.4 Analyses

We conducted descriptive statistics to assess feasibility, patient-reported outcomes, and inflammation and Mann-Whitney U tests to compare groups.

3. Results

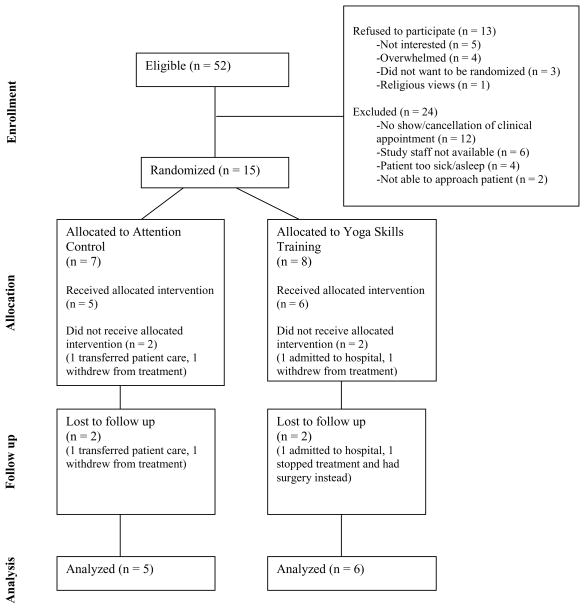

Of 52 patients identified, 28 were approached, and 15 (54%) enrolled (Figure 1). Twenty-four of those initially identified could not be contacted. Participants had a median age of 61.0 years, and a majority were White and male (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Study Flow Diagram

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics (N=15)

| Baseline Characteristics | N |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 9 |

| Female | 6 |

| Race | |

| White | 12 |

| Black | 3 |

| Other | 0 |

| Hispanic | 0 |

| Marital Status | |

| Married or Living with Partner | 13 |

| Separated, Divorced or Widowed | 2 |

| Education | |

| High School Education or Less | 2 |

| Some Post-high School | 4 |

| College/Post-graduate Degree | 8 |

| Primary Diagnosis | |

| Colon Cancer | 10 |

| Rectal Cancer | 5 |

| Stage at Diagnosis | |

| 0–II | 4 |

| III | 6 |

| IV | 5 |

| Treatment for Recurrent Disease | |

| Yes | 6 |

| No | 9 |

| Performance Status (ECOG) | |

| 0 | 3 |

| 1 | 11 |

| 2 | 1 |

| Median (Inter Quartile Range) | |

| Age | 61.0 (44.0–67.0) |

| Fatigue (Possible Range: 0–52.0) | 43.0 (36.0–49.0) |

| Sleep Quality (Possible Range: 0–16.0) | 10.0 (5.0–12.0) |

| Quality of Life (Possible Range: 0–136.0) | 104.0 (87.5–112.0) |

| Interleukin 6 | 2.17 (1.47–3.90) |

| Interleukin 1 receptor agonist | 309.5 (248.22–367.47) |

| Soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 | 1124.10 (856.28–1529.20) |

| Tumor necrosis factor alpha | 1.11 (0.81–1.82) |

| C-reactive protein | 4.6 (2.2–7.0) |

Note. Numbers may not add up to 15 due to missing data. ECOG = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

Two participants were lost to follow-up in each arm due to cancer treatment changes (73% retention). Intervention adherence to the three in-person sessions for both groups was 76% (of those consented: YST: 18 of 24 sessions; AC: 16 of 21 sessions) or 97% (of those retained in study). The median length of each intervention session was significantly different by arm with a median of 30.0 minutes (interquartile range [IQR]=25.0–37.5) for the YST arm and 20.0 minutes (IQR=20.0–27.5) for the AC arm (p<0.05). A higher proportion of the participants indicated that they used the home practice recording in the past two weeks (yes/no) in the YST arm (week 4 [4 of 5]; week 8 [4 of 6]) as compared to the AC arm (week 4 [2 of 5]; week 8 [3 of 5]). All participants indicated that they liked the interventions (YST median=3.0; AC median=3.0) and found them somewhat helpful (YST median=2.0; AC median=2.0).

Participants retained in the study also completed all questionnaires except one person in the YST arm who did not provide baseline data on quality of life. Study outcomes at baseline are described in Table 1. No differences were found between groups (Table A.2).

Table A.2.

Study Outcomes and Group Comparisons

| Yoga Skills Training | Attention Control | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Post-Intervention | Change from Baseline | Baseline | Post-Intervention | Change from Baseline | ||||||

| N | Median | N | Median | Median | N | Median | N | Median | Median | p-valuea | |

| Fatigue | 8 | 36.00 | 6 | 34.00 | −8.00 | 7 | 44.00 | 5 | 29.00 | −7.00 | 0.581 |

| IQR | (25.50–48.00) | (11.75–41.50) | (−16.00–1.00) | (40.00–49.00) | (24.50–38.50) | (−20.00–−5.50) | |||||

| Sleep Quality | 8 | 10.00 | 6 | 10.00 | −0.50 | 7 | 10.00 | 5 | 8.00 | 0.00 | 0.783 |

| IQR | (5.25–15.75) | (5.50–15.50) | (−2.75–2.00) | (5.00–10.00) | (5.00–13.50) | (−2.50–2.50) | |||||

| Quality of Life | 8 | 99.00 | 5 | 88.28 | 1.00 | 7 | 110.00 | 5 | 105.00 | −4.00 | 0.754 |

| IQR | (68.50–109.00) | (59.00–109.70) | (−8.00–10.70) | (97.00–117.00) | (94.00–113.50) | (−17.00–6.50) | |||||

| IL-6 | 8 | 1.88 | 6 | 3.21 | 0.11 | 7 | 2.17 | 5 | 4.59 | 0.12 | 0.715 |

| IQR | (0.94–3.50) | (1.44–9.66) | (−9.12–1.86) | (1.59–7.90) | (3.10–9.32) | (−2.63–4.89) | |||||

| IL-1Ra | 8 | 287.42 | 6 | 334.18 | 38.28 | 7 | 317.16 | 5 | 367.08 | 36.56 | 0.855 |

| IQR | (183.73–392.53) | (176.03–510.01) | (−101.18–178.65) | (279.68–367.47) | (192.68–767.54) | (−184.26–317.30) | |||||

| sTNF-R1 | 8 | 990.62 | 6 | 992.82 | 53.65 | 7 | 1335.50 | 5 | 1100.2 | 71.60 | 0.715 |

| IQR | (816.49–1520.50) | (874.52–1713.50) | (−1.02–191.25) | (992.73–1529.20) | (924.44–1593.30) | (2.55–216.50) | |||||

| TNF-alpha | 8 | 1.49 | 6 | 1.27 | −0.15 | 7 | 1.02 | 5 | 1.69 | 0.13 | 0.273 |

| IQR | (0.88–2.03) | (1.03–2.09) | (−0.38–0.46) | (0.69–1.76) | (0.70–1.91) | (−0.16–0.97) | |||||

| CRP | 8 | 3.75 | 6 | 3.55 | −0.73 | 7 | 5.20 | 5 | 5.60 | 0.30 | 0.361 |

| IQR | (1.53–10.53) | (1.26–8.95) | (−3.88–1.98) | (2.20–7.00) | (2.70–34.20) | (−2.10–12.80) | |||||

Note. IQR = Interquartile range

Results from a Mann-Whitney U test comparing change from baseline in the YST to AC.

4. Discussion

This pilot study supported the feasibility of conducting a larger randomized controlled trial to assess the YST as compared to an attention control group among patients in the clinical setting during chemotherapy for colorectal cancer. In particular, the retention rate of 73% was greater than what was determined a priori as reasonable.

In addition, lessons to strengthen the next phase of study were learned. For example, increasing study staff availability and clearly describing potential benefits would improve recruitment. Further, the interventions were perceived as equally helpful and future studies should plan for additional implementation time (20–30 minutes). It may also be beneficial to enhance the dose of the interventions to increase efficacy and to modify the method of home practice in the AC arm to be more engaging and improve adherence (e.g., provide more targeted information to participants, have participants journal about their experience during treatment).

A feasible rate of questionnaire completion was demonstrated, although future studies could improve study retention by following-up with participants who changed cancer treatment plans yet completed at least one of the study interventions (e.g., via mail or internet survey). In addition, baseline data on proposed outcomes showed similar levels of fatigue, sleep disturbance, quality of life and inflammation as reported in other studies of comparable populations [3, 9, 13, 14]. These data will inform future studies to further evaluate the YST, which has the potential to expand the reach of yoga to patients in clinical settings.

Highlights.

This pilot study supported feasibility of investigating a brief yoga intervention.

The novel yoga intervention is implemented in the clinic during chemotherapy.

Lessons learned will strengthen studies to further evaluate the intervention.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Cancer Institute (R25 CA122061) and National Center For Complementary & Integrative Medicine (K01AT008219; K23AT006965) of the National Institutes of Health. It was also supported by the Center for Integrative Medicine, Wake Forest School of Medicine. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. In addition, we acknowledge Jnani Chapman RN, RYT and Lynn Felder, RYT for contributing to development of the yoga intervention.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Miller AH, Ancoli-Israel S, Bower JE, Capuron L, Irwin MR. Neuroendocrine-immune mechanisms of behavioral comorbidities in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:971–982. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.7805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jim HSL, Small B, Faul LA, Franzen J, Apte S, Jacobsen PB. Fatigue, depression, sleep, and activity during chemotherapy: daily and intraday variation and relationships among symptom changes. Ann Behav Med. 2011;42:321–333. doi: 10.1007/s12160-011-9294-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang XS, Williams LA, Krishnan S, Liao Z, Liu P, Mao L, Shi Q, Mobley GM, Woodruff JF, Cleeland CS. Serum sTNF-R1, IL-6, and the development of fatigue in patients with gastrointestinal cancer undergoing chemoradiation therapy. Brain Behav Immun. 2012;26:699–705. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2011.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aprile G, Ramoni M, Keefe D, Sonis S. Application of distance matrices to define associations between acute toxicities in colorectal cancer patients receiving chemotherapy. Cancer. 2008;112:284–292. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bower JE, Garet D, Sternlieb B, Ganz PA, Irwin MR, Olmstead R, Greendale G. Yoga for persistent fatigue in breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Cancer. 2012;118:3766–3775. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mustian KM, Janelsins M, Peppone LJ, Kamen C. Yoga for the Treatment of Insomnia among Cancer Patients: Evidence, Mechanisms of Action, and Clinical Recommendations. Oncol Hematol Rev. 2014;10:164–168. doi: 10.17925/ohr.2014.10.2.164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cramer H, Pokhrel B, Fester C, Meier B, Gass F, Lauche R, et al. A randomized controlled bicenter trial of yoga for patients with colorectal cancer. Psychooncology. 2015 doi: 10.1002/pon.3927. ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Christian L, Preston H, Houts CR, Malarkey WB, Emery CF, Glaser R. Stress, inflammation, and yoga practice. Psychosom Med. 2010;72:113–121. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181cb9377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen L, Warneke C, Fouladi RT, Rodriguez MA, Chaoul-Reich A. Psychological adjustment and sleep quality in a randomized trial of the effects of a Tibetian yoga intervention in patients with Lymphoma. Cancer. 2004;100:2253–2260. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yellen SB, Cella D, Webster K, Blendowski C, Kaplan E. Measuring fatigue and other anemia-related symptoms with the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) measurement system. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1997;13:63–74. doi: 10.1016/S0885-3924(96)00274-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ward WL, Hahn EA, Mo F, Hernandez L, Tulsky DS, Cella D. Reliability and validity of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Colorectal (FACT-C) quality of life instrument. Qual Life Res. 1999;8:181–195. doi: 10.1023/a:1008821826499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buysse DJ, Yu L, Moul DE, et al. Development and validation of patient-reported outcome measures for sleep disturbance and sleep-related impairments. Sleep. 2010;33:781–792. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.6.781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cella D, Lai J-S, Chang C-H, Peterman A, Slavin M. Fatigue in cancer patients compared with fatigue in the general United States population. Cancer. 2002;94:528–538. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yost KJ, Cella D, Chawla A, Holmgren E, Eton DT, Ayanian JZ, West DW. Minimally important differences were estimated for the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Colorectal (FACT-C) instrument using a combination of distribution- and anchor-based approaches. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58:1241–1251. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]