Abstract

The primary focus of this study was to assess age related changes in the vertical distance of the estimated level of velopharyngeal closure in relation to a prominent landmark of the cervical spine: the anterior tubercle of cervical vertebrae one (C1). Midsagittal anatomical magnetic resonance images (MRI) were examined across 51 participants with normal head and neck anatomy between 4 and 17 years of age. Results indicate that age is a strong predictor (p = 0.002) of the vertical distance between the level of velopharyngeal closure relative to C1. Specifically, as age increases, the vertical distance between the palatal plane and C1 becomes greater resulting in the level of velopharyngeal closure being located higher above C1 (range 4.88mm to 10.55mm). Results of this study provide insights into the clinical usefulness of using C1 as a surgical landmark for placement of pharyngoplasties in children with repaired cleft palate and persistent hypernasal speech. Clinical implications and future directions are discussed.

INTRODUCTION

The cranial and velopharyngeal soft tissue structures develop and change across the age span.1 Age related changes are evident in the horizontal and vertical dimensions of the vocal tract and contribute to normal velopharyngeal anatomy and function.2 Between 4-17 years of age, vertical growth of the vocal tract causes changes in the angle of the posterior pharyngeal wall, moving from an obtuse angle to an approximately right angle.3 Ursi and colleagues4 found that facial, maxillary, and mandibular growth showed no sexual dimorphism prior to puberty. Perry et al5 demonstrated non-significant gender effects for cranial, velopharyngeal, and levator muscle measures prior to puberty with notable growth variations occurring post-puberty (13-19 years of age). Perry et al6, in agreement with other studies7-10, further demonstrated velopharyngeal closure at or along the palatal plane. Thus, the level of velopharyngeal closure is closely associated with the palatal plane in the child population.7

Velopharyngeal dysfunction (VPD) occurs in approximately 5-38% of children with repaired cleft palate.11 A pharyngoplasty is typically used for surgical correction of VPD. Pharyngoplasties alter the relationship between the posterior pharyngeal wall and the velum. The success of speech outcomes corresponds to the patient's preoperative craniofacial morphology.12,13 Preoperative morphology has primarily been assessed in the orthognathic and dental literature and focused on anterior craniofacial structures.13 Craniofacial soft tissue structures and their functions have further been a focus of recent studies14-18. Specifics of the craniofacial structures and the upper cervical spine along with changes across the age span as they relate to surgical outcomes warrant further analysis. Specifically, it is not well understood how growth and angulation changes in the pharyngeal cavity effect the decisions of optimal surgical placement.

An estimated 13-23% of patients will have a failed pharyngoplasty that requires a surgical revision.19-21 Riski et al22 observed the primary cause of failed pharyngoplasty was insertion of the flap below the point of optimal velopharyngeal closure. Studies have emphasized the importance of placement of the pharyngoplasty as it relates to speech outcome20,23,24, suggesting placement at or above the level of velopharyngeal closure20,22,24. However, clinical methods tend to be less prescriptive indicating placement should be “as high as possible.” The first cervical vertebra (C1) or the level of velopharyngeal closure have been recommended as landmarks for identifying placement of the pharyngoplasty prior to and during surgery in order to ensure the pharyngoplasty is at an optimal level for normal resonance postsurgically. To our knowledge, no studies have quantified the optimal level of insertion of pharyngoplasties relative to any bony or palpable intraoperative landmarks. Given the range in age of surgery for pharyngoplasties can be extensive (2-17 years of age), further information is needed to understand how changes in the pharynx due to growth effect the relationship of C1 to level of velopharyngeal closure. It is expected that as the vocal tract lengthens and changes in the vertical configuration occur across the age span, the relationship between C1 and palatal plane will likely be altered. Research is needed to understand the relationship of palatal plane in normal anatomy relative to age related changes in the cervical spine to determine the need for future research with clinical populations.

The purpose of this study is to determine if C1 remains at the same location relative to the level of velopharyngeal closure (using the palatal plane as a reference line) across a selected age span. Consistent with vocal tract literature demonstrating cervical growth patterns across the age span25-27, it is expected that the relationship between C1 and the palatal plane will show similar changes with age. Specifically, we hypothesize that the vertical distance between C1 and the level of velopharyngeal closure will increase with age. This study seeks to examine age related changes and the usefulness of the palatal plane in relation to the cervical spine for evaluating the level of velopharyngeal closure.

METHODS

Participants

In accordance with the University Medical Center Institutional Review Board (UMIRB) 51 participants were recruited to participate in the study. Male and female participants (26 male, 25 female) were included between the ages of 4 and 17 years (mean, 9.59; SD 4.383). Participants were stratified across age groups including 15 child participants (4-6 years of age; mean 4.87 ± 0.83), 17 prepubescent participants (7-9 years of age; mean 8.18 ± 0.883), 6 peri-pubescent participants (10-14 years of age; mean 11.67 ± 1.86) and 13 adolescent/post-pubescent participants (14-17 years of age; mean 15.92 ± 0.64). Age groups were selected based on the stages of development from childhood through adolescence and notable changes that are known to occur with the craniofacial and skeletal development during puberty.28 A similar number of boys and girls were recruited within each age category. Prior studies have demonstrated no gender effects in craniometric and velopharyngeal measures prior to puberty.2,29 Therefore, we do not expect the majority of data from the present study to be influenced by gender. Participants reported no history of craniofacial, cervical spine abnormalities, neurological, swallowing, or musculoskeletal disorders. No syndromic conditions were reported. Oral exam and a 7-point perceptual rating scale confirmed normal oral anatomy and normal resonance. Midsagittal MR images were examined to ensure exclusion of participants with cervical spine abnormalities.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

Procedures for MRI scanning have been previously described.18 Participants were scanned using a Siemens 3 Tesla Trio (Erlangen, Germany) and a 12-channel Siemens Trio head coil. During the 5-minute scan, participants were instructed to breathe through their nose with their mouth closed. Previous studies have found that supine imaging data can be translated to an upright activity such as speech.18,29,30 Thus, imaging was obtained while in the supine position allowing the velum to rest in a relaxed and lowered position.

A Velcro-fastened elastic strap was placed around the participant's head, passing above the glabella and fastened to the head coil to reduce head motion. A high-resolution, T2-weighted turbo-spin-echo (TSE) three-dimensional anatomical scan called SPACE (Sampling Perfection with Application optimized Contrasts using different flip angle Evolution) was used to acquire a large field of view covering the oropharyngeal anatomy (25.6 × 19.2 × 15.5 cm) with 0.8 mm in plane isotropic resolution with an acquisition time of slightly less than 5 minutes (4:52). Echo time (TE) was 268 milliseconds, and repetition time (TR) was 2.5 seconds.

Image Analysis

MRI data were transferred into Amira 5.6 Visualization and Volume Modeling software (Mercury Company Systems Inc, Chelmsford, MA), which has a built-in native Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) support program. This software ensures the anatomical geometry (e.g., aspect ratio, scaling dimension, and image resolution) is maintained when importing images into the program. The midsagittal plane was determined by identifying the section plane that most clearly depicts the complete nasal septum, genu of the corpus callosum, and outline of the fourth ventricle. Quantitative measures of the cranial base angle, the line of the palatal plane estimating velopharyngeal contact to the posterior pharyngeal wall, vertical distance of estimated velopharyngeal contact to C1, pharyngeal depth, and velar length were obtained from the midsagittal MRI plane (Figure 2). Cranial base angle and the velar/pharyngeal depth to length ratios were then computed. Means and standard deviations are displayed in Table 2. Descriptions of these measures obtained at rest, similar to Tian et al31, are further enumerated below.

-

a)

Cranial Base Angle: Angle created by the intersection of the nasion-sella line and sella-basion line.

-

b)

Velar Length: Curvilinear distance between the posterior border of the hard palate (PNS) and center of the uvula at rest.

-

c)

Pharyngeal Depth: Distance from velar knee at rest to the posterior pharyngeal wall drawn parallel to palatal plane.

-

d)

Nasopharyngeal Depth (PNS to PPW): Distance between the posterior border of the hard palate (PNS) and the posterior pharyngeal wall (PPW).

-

e)

Palatal Plane Reference Line: Line drawn through the body of the hard palate and extending posteriorly through the posterior pharyngeal wall.

-

f)

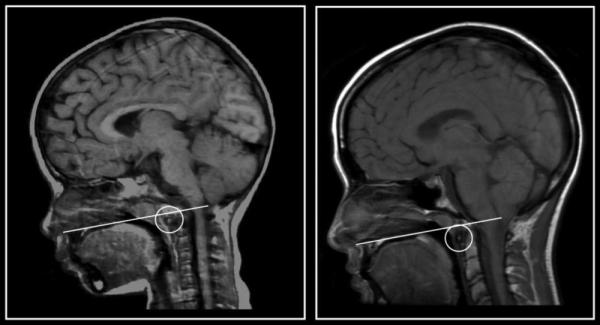

Vertical Distance from Palatal Plane Reference Line Relative to C1: Distance from the anterior tubercle of C1 vertically (coursing parallel to the pharyngeal wall) to the palatal plane reference line (Figure 1).

Figure 2.

Sample Measures Obtained.

Table 2.

Means and standard deviations for measures across age groups (in mm)

| Age Group | Cranial Base Angle | Pharyngeal Depth | Velar Length | PNS to PPW | Vertical Distance between PP and C1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child Ages 4-6 | 130.63° ± 3.35 | 7.88 ± 1.10 | 24.39 ± 1.81 | 18.69 ± 3.43 | 6.94 ± 1.15 |

| Prepubescent Ages 7-9 | 130.66° ± 1.82 | 8.27 ± 1.22 | 27.30 ± 2.47 | 19.75 ± 3.18 | 7.77 ± 1.23 |

| Peripubescent Ages 10-14 | 128.35° ± 4.33 | 10.07 ± 2.47 | 28.21 ± 0.99 | 19.92 ± 2.50 | 8.82 ± 1.04 |

| Postpubescent Ages 15-17 | 130.20° ± 2.53 | 11.02 ± 1.87 | 32.17 ± 3.53 | 24.95 ± 4.06 | 8.28 ± 1.93 |

| Overall Mean Mean age 9.59 | 130.26° ± 2.86 | 9.07 ± 2.00 | 27.79 ± 3.81 | 20.78 ± 4.17 | 7.78 ± 1.51 |

Figure 1.

Reference line of the palatal plane and vertical distance between the anterior tubercle of C1 and the level of velopharyngeal closure.

The Pearson product moment correlation (α = 0.05) was used to establish interrater and intrarater reliability measures. Reliability measurements were completed on 10 randomly selected mid-sagittal MRI slices by the primary and secondary raters 3 weeks after the first measures were obtained. Both raters have prior experience in measuring the areas and structures in this study. The interrater and intrarater reliability ranged from r = .98 to r =.99.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) on 51 children to determine age variations and interactions among craniometric variables including vertical distance of the palatal plane relative to C1, pharyngeal depth, velar length, and cranial base angle. A two sample t-test on gender and cranial measures (the vertical distance of the level of VP closure to C1) were used to assess the homogeneity of our sample to determine if differences were present secondary to sexual dimorphism within each age group.

An analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) using the general linear model procedure in SPSS (IBM Corp.) was used to determine the interactions between age and vertical distance of the estimated level of velopharyngeal closure to C1 using the covariate of race to control for the effects of racial difference on cranial measures.

Linear regression analysis was performed to determine whether age could be used to predict the vertical distance of the estimated level of velopharyngeal closure relative to C1. It was hypothesized that age would affect the vertical distance of the palatal plane/estimated level of velopharyngeal closure relative to C1. Cranial base angle was found to be consistent across all measures, thus it was not included in the statistical analyses or regression model.

RESULTS

Two sample t-tests were used to assess if gender differences secondary to pubertal growth effects were present within groups. No statistically significant differences were seen related to sexual dimorphism across all groups (Table 1). This indicates that for the measures used in the present study, there do not appear to be gender differences within each group.

Table 1.

No Significant Differences in PP to C1 between Male vs Female within Age Groups

| Paired Samples T-Test | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Male | Mean Female | Significance | |

| Child Age 4-6 | −7.21 ± 1.04 | −6.63 ± 1.28 | 0.352 |

| Prepubescent Age 7-9 | −8.01 ± 1.25 | −7.49 ± 1.23 | 0.402 |

| Peripubescent Age 10-14 | −9.725 ± 0.71 | −8.365 ± 0.90 | 0.142 |

| Postpubescent Age 15-17 | −9.025 ± 1.61 | −7.649 ± 2.06 | 0.213 |

*p = 0.05

Means and standard deviations are reported for craniometric measures on all participants (Table 2). Cranial base angle was found to be consistent across all participants with little variability between age and gender groups. Pharyngeal depth increased across the age span for all participants with the largest increase noted from the pre- to peri-pubescent group, followed closely by the adolescent/post-pubescent group. Velar length was noted to increase, with the greatest difference in means noted between the peri-pubescent and post-pubescent groups. Values within our sample were consistent with previous literature.1 The variability observed in the vertical distance between the level of VP closure and C1 was demonstrated by a large spread across measures in the post-pubescent age group (4.91 to 10.55 mm). This is in contrast to the child and pre-pubescent groups which had smaller spreads (4.88 to 9.51 mm and 5.87 to 9.69 mm, respectively).

Regression analysis was performed to determine if age was a predictor of the vertical distance from the level of VP closure to C1. Age, when treated as a continuous variable, was found to be statistically significant (p = 0.002). A moderate correlation (R = 0.402) was observed across all participant measures of vertical distance (Figure 5). In such, C1 becomes farther below the estimated level of velopharyngeal closure with an increase in age (Figure 3).

Figure 5.

Regression of age (in years) to vertical distance (in mm) between level of VP closure and C1.

Figure 3.

Example of vertical distance between C1 and palatal plane in a 4 year old female compared to a 17 year old female.

Greater variability in the vertical distance of palatal plane to C1 was observed in the peri-pubescent and adolescent group compared to the child and pre-pubescent age groups (Figure 4). Specifically, after age 10, the downward trend becomes less apparent due to the variability in vertical distance. This indicates that between the ages of 4-9, vertical distance between C1 and the level of velopharyngeal closure steadily increases. Following age 10, variability in the vertical distance between participants was observed (indicating differences in the peri-pubertal growth spurts) and greater vertical distances were measured. Thus, age is a stronger predictor of the vertical distance for the child group (ages 4-9). During the peri-pubertal and post-pubertal stages it is likely that other pubertal growth factors may begin to play a larger role.

Figure 4.

Mean vertical distance of palatal plane to C1 across age span.

An analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was completed across age groups (child, prepubescent, peri-pubescent, and adolescent) with race treated as a covariate to determine if differences in the mean vertical distance between the level of closure and C1 for each group were present between age groups. Results were statistically significant at α = 0.05 (p = 0.029). A Bonferoni post-hoc test revealed the greatest difference occurred between the child and adolescent groups.

DISCUSSION

Historically, the palatal plane has been defined as the measure of the anterior nasal spine (ANS) to the posterior nasal spine (PNS).7,27,32,33 These structures create easily recognizable landmarks. However, consistent with past studies34-36, significant variability was seen in the location and prominence of the ANS across the images in the present study. This noted variability included a higher curving or more superiorly placed ANS in some individuals. This influences the line of reference drawn through to the PNS. Further, it has been reported that the ANS can be significantly angled both superiorly and inferiorly in the cleft lip and palate population37, can vary by race34, and patients with cleft palate do not display a prominent PNS.38 The use of the ptergomaxillary fissure is suggested to estimate the location of the PNS in the cleft population.38,39 Frequently, when using the ANS-PNS line for participants within our sample, the body of the palate was disregarded and the reference line did not course directly through the body of the palate with differing variations of the ANS. Thus, this study used the body of the palate through the PNS (directly below the ptergomaxillary fissure in normal participants) to determine the level of the palatal plane as an estimator of velopharyngeal closure or contact with the PPW. This allowed for the creation of a consistent plane of reference for which to measure an estimated level of velopharyngeal closure (against the posterior pharyngeal wall). Past literature has demonstrated velopharyngeal closure occurs along this palatal plane reference line8,10, however, it is expected that changes in velar contact along the posterior pharyngeal wall demonstrate a pubertal shift that is beyond the age range used in the present study. In such, velar height variations that have been demonstrated in adult populations40,41 are likely not evident in the age ranges used in the present study. This is consistent with prior studies examining velar variations across the age span.4

Similar to Ursi et al4, cranial base angle values in the present study were consistent across all age groups, with minimal variation between males and females. Despite known increases in head size for boys and girls across the age span, cranial base angle remains consistent across age and gender for the age range used in the present study. Pharyngeal depth and velar length showed a trend to increase with age. These findings are similar to those found by Subtelny1 and parallel the consistent increase found in studies of velar length and nasopharyngeal depth.1,25,42 Within each age group, no significant differences in cranial measures were noted. Due to the majority of our data being from pre-pubertal participants, these results were expected. Non-significant gender differences are consistent with findings from Perry et al2 in which sexual dimorphism of cranial and velopharyngeal variables were primarily evident in post-pubertal age groups. However, variability in the vertical distance between the palatal plane and C1 was noted across age groups and most significantly observed in the peri- and post-pubescent age groups. This variability is likely due to changes in the vocal tract descent and angulation.2

Previous studies have assessed height of insertion of pharyngoplasties relative to C1.22,23,43 Riski et al23 demonstrated that the insertion height of the pharyngoplasty appeared to be a critical factor in surgical success. However, quantification for the ideal height of insertion has not been reported. To our knowledge, no studies have examined how this palpable bony landmark (C1) relative to the palatal plane and level of velopharyngeal closure may change with age. The anterior tubercle of C1 is commonly palpated and used as an identifying landmark for the placement of tissue during surgical insertion of a pharyngoplasty.22 Our study sought to assess if age related changes affected the vertical distance from the level of velopharyngeal closure to C1. Our results indicate age is significantly correlated to the vertical distance between the palatal plane (point of velopharyngeal contact against the posterior pharyngeal wall) and the anterior tubercle of C1 (p = 0.002, α = 0.05).

Statistically significant correlations were further present for age as a predictor in the level of velopharyngeal closure relative to the vertical distance above C1. As age increases, the level of velopharyngeal closure is higher above C1. This is likely due to the accelerated growth of the vertebral column.26 The anterior tubercle of C1 was consistently below the level of velopharyngeal closure in all participants. Quantitatively, a range of 4.88mm to 10.55mm was seen in the vertical distance between C1 and palatal plane across the age span of 4-17 years. Table 2 displays the mean vertical distance between C1 and palatal plane within each age group. Our data suggest that age affects the vertical distance between C1 and the level of velopharyngeal closure among the child population. Contrary to previous tracings of craniofacial growth3,44, which illustrate smaller distances between C1 and the palatal plane as the child ages, data from this study demonstrate an increased distance between the level of velopharyngeal closure and the palatal plane as the child ages.

This study highlights anatomical landmarks in a normal population that can be utilized as a reference for a disordered population. Previous studies have primarily focused on outcomes for specific speech surgeries and techniques to improve their success with little focus on a patient's preoperative bony anatomy as it relates to the structural development and function of the velopharyngeal mechanism.45,46 Ysunza et al46 primarily utilized the assessment of lateral wall motion, velopharyngeal gap size, and level of maximum displacement of the velopharyngeal sphincter. In regards to bony anatomy, Krogman et al47 found that palatal clefting affects the bony structures of the cranial base and the facial skeleton. Thus, the level of the palatal plane and its relation to the cervical spine as it relates to velopharyngeal closure is of interest. Wada et al32 found that the cranial base and upper cervical vertebrae growth is independent to cleft or cleft surgery effects. However, inhibition of growth at the posterior maxilla results in morphological asynchrony in upper nasopharyngeal structures and could be a sign of potential reappearance of velopharyngeal inadequacy at an older age. Satoh et al27 found that lateral cephalograms identified nasopharyngeal growth and morphological changes, but no information was found regarding velopharyngeal closure. Further, Shibaski and Ross48 found children with repaired cleft exhibited an overall decreased growth in length and height of the maxilla in comparison to children with normal anatomy. The extent to which the above cranial variables may affect the vertical distance of VP closure relative to C1 remains unknown. It is suspected that age related pubertal changes to cranial variables in a normal population may contribute to the observed variability in the vertical distance between C1 and palatal plane that was noted in the peri-pubescent and post-pubescent age groups.

Limitations

The variability seen in the peri- and post-pubescent age groups may have resulted from the cross sectional nature of the study design. Utilizing a long term, longitudinal analysis of participants may result in a stronger relationship between age and the vertical distance between the palatal plane and C1. Increased variability noted in the peri-pubertal age group may further be exacerbated due to a smaller sample size within that age group. If analyzed longitudinally, a more consistent trend and stronger correlation between age and the vertical distance of palatal plane to C1 may be seen.

Clinical Applications and Future Research

MRI was successfully used to visualize the velopharyngeal mechanism and related anatomical structures. MRI and other 3D imaging modalities have proven to be a sound technique for the analysis of the velopharyngeal musculature as well as for the study of growth and treatment response.49-51 MR imaging can further facilitate the diagnostic process. Measurements obtained through MRI allow information to be assessed quantitatively and non-invasively. Further, greater accuracy in craniometric measures of cranial base angle, velar length, pharyngeal depth and the level of velopharyngeal closure are possible.

The understanding and quantification of normal anatomical locations of the palatal plane and level of velopharyngeal closure relative to the cervical spine may benefit in the advancement of knowledge for the modeling and creation of a functional post-operative anatomy for individuals with VPD, especially those who undergo pharyngoplasties. Further, data suggests that utilizing the measure of vertical distance between palatal plane and C1 preoperatively may be of clinical interest in patients who undergo secondary speech surgeries due to the change in the vertical distance between these landmarks as the child ages. Future research is needed to examine the feasibility and clinical utility of using measures between C1 and palatal plane as a reference point for surgical approaches and outcomes in the cleft palate population.

Data suggests that as a child ages, specifically between the ages of 4-9, an increase in the vertical distance is observed between the anterior tubercle of C1 and the palatal plane. This may infer that for children undergoing secondary surgical treatment for VPD, the pharyngoplasty may need to be placed higher in the nasopharynx relative to C1. Secondarily, since C1 consistently resided significantly below the level of velopharyngeal closure, it can be inferred that placement of the sphincter flaps or pharyngeal flaps at C1 would result in a pharyngoplasty positioned below the level of effective VP closure. Poor surgical outcomes, secondary to placement of pharyngoplasty below the point of velopharyngeal contact, could be further exacerbated if surgical placement at C1 occurs after the age of 10, due to a greater distance between C1 and the palatal plane being present. Future research is needed to examine outcomes from pharyngoplasties relative to the data presented in the present study.

CONCLUSION

The purpose of this study was to determine if C1 remained at the same location relative to the level of velopharyngeal closure using the palatal plane as a reference line. C1 was consistently below the line of the palatal plane. Thus, the level of velopharyngeal closure resides above C1 (range 4.88mm to 10.55mm). Age was a significant predictor of the vertical distance between palatal plane and C1. Results indicated that the vertical distance between C1 and palatal plane increases as the child ages. Greater variability was observed in the vertical distance between C1 and palatal plane in the peri- and pre-pubescent age groups. Data may be extrapolated to a disordered population on further study. Additionally, longitudinal assessment is needed. Results of this study provide clinically useful information and implications for future applications to the assessment and treatment of resonance disorders. Comprehension of normal craniofacial morphology is critical to the understanding of abnormal craniofacial morphology. Normative data presented in this study provide a foundation for future comparative analyses.

Acknowledgements

This study was made possible by grant number 1R03DC009676-01A1 from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communicative Disorders. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health

Contributor Information

Kazlin N. Mason, East Carolina University; Children's Healthcare of Atlanta.

Jamie L. Perry, East Carolina University.

John E. Riski, Children's Healthcare of Atlanta.

Xiangming Fang, East Carolina University.

REFERENCES

- 1.Subtelny JD. A cephalometric study of the growth of the soft palate. Plast Reconstr Surg (1946) 1957;19(1):49–62. doi: 10.1097/00006534-195701000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perry JL, Kollara L, Schenck G, Fang X, Kuehn DP, Sutton BP. Pre and post pubertal changes: The effect of growth on the velopharyngeal anatomy. J Speech Lang Hear Res. doi: 10.1044/2018_JSLHR-S-18-0016. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kent RD, Vorperian HK. Development of the craniofacial-oral-laryngeal anatomy. Singular. 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ursi WJ, Trotman CA, McNamara JA, Jr, Behrents RG. Sexual dimorphism in normal craniofacial growth. Angle Orthod. 1993;63(1):47–56. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1993)063<0047:SDINCG>2.0.CO;2. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1993)063<0047:SDINCG>2.0.CO;2 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perry JL, Kuehn DP, Sutton BP, Gamage JK. Sexual dimorphism of the levator veli palatini muscle: An imaging study. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2014;51(5):544–552. doi: 10.1597/12-128. doi: 10.1597/12-128 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perry JL, Sutton BP, Kuehn DP, Gamage JK. Using MRI for assessing velopharyngeal structures and function. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2014;51(4):476–485. doi: 10.1597/12-083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Satoh K, Wada T, Tachimura T, Sakoda S, Shiba R. A cephalometric study of the relationship between the level of velopharyngeal closure and the palatal plane in patients with repaired cleft palate and controls without clefts. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1999;37(6):486–489. doi: 10.1054/bjom.1999.0187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yoshida H, Stella JP, Ghali GE, Epker BN. The modified superiorly based pharyngeal flap: Part IV. position of the base of the flap. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1992;73(1):13–18. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(92)90146-h. doi: http://dx.doi.org.jproxy.lib.ecu.edu/10.1016/0030-4220(92)90146-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu J, Epker BN. The modified superior based pharyngeal flap technique: Part II. an anatomic study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1990;70(3):251–255. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(90)90136-g. doi: http://dx.doi.org.jproxy.lib.ecu.edu/10.1016/0030-4220(90)90136-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Satoh K, Nagata J, Shomura K, et al. Morphological evaluation of changes in velopharyngeal function following maxillary distraction in patients with repaired cleft palate during mixed dentition. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2004;41(4):355–363. doi: 10.1597/02-153.1. doi: 10.1597/02-153.1 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Witt PD, D'Antonio LL. Velopharyngeal insufficiency and secondary palatal management. A new look at an old problem. Clin Plast Surg. 1993;20(4):707–721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El-Kassaby MA, Abdelrahman NI, Abbass IT. Premaxillary characteristics in complete bilateral cleft lip and palate: A predictor for treatment outcome. Ann Maxillofac Surg. 2013;3(1):11. doi: 10.4103/2231-0746.110064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heliövaara A, Leikola J, Hukki J. Craniofacial cephalometric morphology and later need for orthognathic surgery in 6-year-old children with bilateral cleft lip and palate. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2013;50(2):e35–e40. doi: 10.1597/11-262.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trier WC. Velopharyngeal incompetency in the absence of overt cleft palate: Anatomic and surgical considerations. Cleft Palate J. 1983;20(3):209–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gart MS, Gosain AK. Surgical management of velopharyngeal insufficiency. Clin Plast Surg. 2014;41(2):253–270. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2013.12.010. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2013.12.010 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng N, Zhao M, Qi K, Deng H, Fang Z, Song R. A modified procedure for velopharyngeal sphincteroplasty in primary cleft palate repair and secondary velopharyngeal incompetence treatment and its preliminary results. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2006;59(8):817–825. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang MH, Lee ST, Rajendran K. Anatomic basis of cleft palate and velopharyngeal surgery: Implications from a fresh cadaveric study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;101(3):613–27. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199803000-00007. discussion 628-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perry JL. Variations in velopharyngeal structures between upright and supine positions using upright magnetic resonance imaging. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2011;48(2):123–133. doi: 10.1597/09-256. doi: 10.1597/09-256 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Losken A, Williams JK, Burstein FD, Malick D, Riski JE. An outcome evaluation of sphincter pharyngoplasty for the management of velopharyngeal insufficiency. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;112(7):1755–1761. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000090720.33554.8B. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000090720.33554.8B [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Witt PD, Marsh JL, Marty-Grames L, Muntz HR. Revision of the failed sphincter pharyngoplasty: An outcome assessment. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;96(1):129–138. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199507000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kasten SJ, Buchman SR, Stevenson C, Berger M. A retrospective analysis of revision sphincter pharyngoplasty. Ann Plast Surg. 1997;39(6):583–589. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199712000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Riski JE, Ruff GL, Georgiade GS, Barwick WJ, Edwards PD. Evaluation of the sphincter pharyngoplasty. The Cleft palate-craniofacial journal. 1992;29(3):254–261. doi: 10.1597/1545-1569_1992_029_0254_eotsp_2.3.co_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Riski JE, Ruff GL, Georgiade GS, Barwick WJ, Edwards PD. Evaluation of the sphincter pharyngoplasty. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 1992;29(3):254–261. doi: 10.1597/1545-1569_1992_029_0254_eotsp_2.3.co_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carlisle MP, Sykes KJ, Singhal VK. Outcomes of sphincter pharyngoplasty and palatal lengthening for velopharyngeal insufficiency: A 10-year experience. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;137(8):763–766. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2011.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vorperian HK, Kent RD, Lindstrom MJ, Kalina CM, Gentry LR, Yandell BS. Development of vocal tract length during early childhood: A magnetic resonance imaging study. J Acoust Soc Am. 2005;117(1):338–350. doi: 10.1121/1.1835958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vorperian Houri K Wang, Chung Shubing, Schimek Moo K, Michael Durtschi E, Kent Reid B, Ziegert Ray D, Gentry Andrew J, Lindell R. Anatomic development of the oral and pharyngeal portions of the vocal tract: An imaging study. J Acoust Soc Am. 2009;125(3):1666–1678. doi: 10.1121/1.3075589. doi: 10.1121/1.3075589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Satoh K, Wada T, Tachimura T, Shiba R. The effect of growth of nasopharyngeal structures in velopharyngeal closure in patients with repaired cleft palate and controls without clefts: A cephalometric study. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002;40(2):105–109. doi: 10.1054/bjom.2001.0749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vorperian HK, Wang S, Schimek EM, et al. Developmental sexual dimorphism of the oral and pharyngeal portions of the vocal tract: An imaging study. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2011;54(4):995–1010. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2010/10-0097). doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2010/10-0097) [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kollara L, Perry JL. Effects of gravity on the velopharyngeal structures in children using upright magnetic resonance imaging. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2014;51(6):669–676. doi: 10.1597/13-107. doi: 10.1597/13-107 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bae Y, Kuehn DP, Sutton BP, Conway CA, Perry JL. Three-dimensional magnetic resonance imaging of velopharyngeal structures. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2011;54(6):1538–1545. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2011/10-0021). doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2011/10-0021) [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tian W, Yin H, Redett RJ, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging assessment of the velopharyngeal mechanism at rest and during speech in chinese adults and children. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2010;53(6):1595–1615. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2010/09-0105). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wada T, Satoh K, Tachimura T, Tatsuta U. Comparison of nasopharyngeal growth between patients with clefts and noncleft controls. Cleft Palate J. 1997;34(5):405–409. doi: 10.1597/1545-1569_1997_034_0405_congbp_2.3.co_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Courtney M, Harkness M, Herbison P. Maxillary and cranial base changes during treatment with functional appliances. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1996;109(6):616–624. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(96)70073-2. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0889-5406(96)70073-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mooney MP, Siegel MI. Developmental relationship between premaxillary-maxillary suture patency and anterior nasal spine morphology. Cleft Palate J. 1986;23(2):101–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Durtschi RB, Chung D, Gentry LR, Chung MK, Vorperian HK. Developmental craniofacial anthropometry: Assessment of race effects. Clin Anat. 2009;22(7):800–808. doi: 10.1002/ca.20852. doi: 10.1002/ca.20852 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harris JE, Kowalski CJ, LeVasseur FA, Nasjleti CE, Walker GF. Age and race as factors in craniofacial growth and development. J Dent Res. 1977;56(3):266–274. doi: 10.1177/00220345770560031201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Molsted K, Dahl E. Asymmetry of the maxilla in children with complete unilateral cleft lip and palate. Cleft Palate J. 1990;27(2):184–90. doi: 10.1597/1545-1569(1990)027<0184:aotmic>2.3.co;2. discussion 190-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bishara SE. Cephalometric evaluation of facial growth in operated and non-operated individuals with isolated clefts of the palate. Cleft Palate J. 1973;10(3):239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Graber TM. A cephalometric analysis of the developmental pattern and facial morphology in cleft palate. Angle Orthod. 1949;19(2):91–100. [Google Scholar]

- 40.McKerns D, Bzoch KR. Variations in velopharyngeal valving: The factor of sex. Cleft Palate J. 1970;7:652–662. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kuehn DP, Folkins JW, Cutting CB. Relationships between muscle activity and velar position. Cleft Palate J. 1982;19(1):25–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tian W, Redett RJ. New velopharyngeal measurements at rest and during speech: Implications and applications. J Craniofac Surg. 2009;20(2):532–539. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e31819b9fbe. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e31819b9fbe [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Witt PD, D'Antonio LL, Zimmerman GJ, Marsh JL. Sphincter pharyngoplasty; A preoperative and postoperative analysis of perceptual speech characteristics and endoscopic studies of velopharyngeal function. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;93(6):1154–1168. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199405000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Coccaro PJ, Pruzansky S, Subtelny JD. Nasopharyngeal growth. Cleft Palate J. 1967;4:214–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sloan GM. Posterior pharyngeal flap and sphincter pharyngoplasty: The state of the art. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2000;37(2):112–122. doi: 10.1597/1545-1569_2000_037_0112_ppfasp_2.3.co_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ysunza A, Pamplona MC, Molina F, et al. Surgery for speech in cleft palate patients. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2004;68(12):1499–1505. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Krogman WM. Craniofacial growth and development: An appraisal. J Am Dent Assoc. 1973;87(5):1037–1043. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1973.0018. http://dx.doi.org/10.14219/jada.archive.1973.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shibasaki Y, Ross R. Facial growth in children with isolated cleft palate. Cleft Palate J. 1969;6(290-302):49–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Atik B, Bekerecioglu M, Tan O, Etlik O, Davran R, Arslan H. Evaluation of dynamic magnetic resonance imaging in assessing velopharyngeal insufficiency during phonation. J Craniofac Surg. 2008;19(3):566–572. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e31816ae746. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e31816ae746 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Perry JL, Kuehn DP, Sutton BP. Morphology of the levator veli palatini muscle using magnetic resonance imaging. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2013;50(1):64–75. doi: 10.1597/11-125. doi: 10.1597/11-125 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Silveira AM, Sommers EW, Katzberg RW, Subtelny JD, Tallents RH, Sanchez-Woodworth R. Three-dimensional computerized tomographic scanning of craniofacial anomalies. Cranio. 1988;6(3):217–223. doi: 10.1080/08869634.1988.11678241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]