Abstract

Mutations in MCOLN1, which encodes the cation channel protein TRPML1, result in the neurodegenerative lysosomal storage disorder Mucolipidosis type IV. Mucolipidosis type IV patients show lysosomal dysfunction in many tissues and neuronal cell death. The ortholog of TRPML1 in Caenorhabditis elegans is CUP-5; loss of CUP-5 results in lysosomal dysfunction in many tissues and death of developing intestinal cells that results in embryonic lethality. We previously showed that a null mutation in the ATP-Binding Cassette transporter MRP-4 rescues the lysosomal defect and embryonic lethality of cup-5(null) worms. Here we show that reducing levels of the Endosomal Sorting Complex Required for Transport (ESCRT)-associated proteins DID-2, USP-50, and ALX-1/EGO-2, which mediate the final de-ubiquitination step of integral membrane proteins being sequestered into late endosomes, also almost fully suppresses cup-5(null) mutant lysosomal defects and embryonic lethality. Indeed, we show that MRP-4 protein is hypo-ubiquitinated in the absence of CUP-5 and that reducing levels of ESCRT-associated proteins suppresses this hypo-ubiquitination. Thus, increased ESCRT-associated de-ubiquitinating activity mediates the lysosomal defects and corresponding cell death phenotypes in the absence of CUP-5.

Keywords: CUP-5, ESCRT, lysosome, mucolipidosis type IV, TRPML1

MUCOLIPIDOSIS type IV (MLIV) is a neurodegenerative lysosomal storage disorder characterized by corneal clouding, achlorhydria, and psychomotor defects (Bach 2001; Altarescu et al. 2002). In MLIV patients, large lipid-rich vacuoles are found in many tissues, while psychomotor defects are thought to be due to neuronal cell death. MLIV is caused by mutations in MCOLN1, which encodes the human protein mucolipin-1/TRPML1; this protein belongs to the transient receptor potential cation channel family and is a nonselective cation channel (Bargal et al. 2000; Bassi et al. 2000; Sun et al. 2000; Laplante et al. 2002; Raychowdhury et al. 2004; Dong et al. 2008).

Caenorhabditis elegans protein CUP-5 is the ortholog of human TRPML1 (Fares and Greenwald 2001b; Hersh et al. 2002). The phenotypes resulting from mutations in cup-5(null) mimic those found in MLIV patients: defective lysosomal degradation and the appearance of large vacuoles in most tissues (Fares and Greenwald 2001b; Schaheen et al. 2006a). In addition, this lysosomal dysfunction in the absence of CUP-5 leads primarily to the death of developing intestinal cells that results in embryonic lethality (Schaheen et al. 2006a). It is not known why developing intestinal cells die in C. elegans or why neurons die in MLIV patients. In C. elegans cup-5(null) mutants, the embryonic lethality is not solely due to cells undergoing apoptosis from starvation; when ATP levels are restored or when apoptosis is blocked, embryonic lethality is only partially rescued (∼14% of embryos hatch and arrest at the L1 larval stage) (Hersh et al. 2002; Schaheen et al. 2006a).

We have shown that C. elegans CUP-5 and mammalian TRPML1 likely function in lysosome formation, which involves the budding of nascent lysosomes from endosomes and scission to release the nascent lysosomes (Treusch et al. 2004; Miller et al. 2015). In contrast to this outward budding event, Endosomal Sorting Complex Required for Transport (ESCRT) proteins are required for the sequestration of integral membrane proteins in intraluminal vesicles through an inward budding and scission event in late endosomes/multivesicular bodies (Henne et al. 2011). This ESCRT-dependent targeting of integral membrane proteins includes an early ubiquitination of the cargo and a late de-ubiquitination required for completion of the scission reaction for internalization into an intraluminal vesicle. This de-ubiquitination is carried out by a complex of ESCRT-associated proteins that include Did2p (Saccharomyces cerevisiae)/CHMP1b (human), Bro1p (S. cerevisiae)/Alix and HD-PTP (human), and Doa4p (S. cerevisiae)/USP8 [UBPY] (human) (Bowers et al. 2004; Reid et al. 2005; Mahul-Mellier et al. 2006; Nickerson et al. 2006; Richter et al. 2007; Row et al. 2007; Ali et al. 2013). Sequestered cargo is transported to lysosomes for degradation. However, the mechanisms coordinating the sequestration of cargo inside late endosomes and their subsequent transport to lysosomes are unknown.

We have previously shown that mutations in mrp-4 suppress the cup-5(null) lysosomal defect and embryonic lethality (Schaheen et al. 2006b). MRP-4 is a member of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter superfamily found in prokaryotes and eukaryotes that use ATP energy for transport of various molecules across membranes (Bauer et al. 1999; Dean et al. 2001; Sheps et al. 2004). Here, we show that reducing levels of worm ESCRT-associated proteins almost completely suppress the lysosomal defect and embryonic lethality due to the loss of CUP-5. Indeed, we show that, in the absence of CUP-5, misregulated ESCRT-associated protein activity results in altered ubiquitination of MRP-4, which leads to embryonic lethality. Our results implicate ESCRT-associated protein defects in cell death and tissue degeneration in this C. elegans model of MLIV.

Materials and Methods

C. elegans strains and methods

Standard methods were used for genetic analysis (Brenner 1974). RNAi was done by the feeding method; control RNAi was done using bacteria expressing the double-stranded RNA generating vector L4440/pPD129.36 (Timmons and Fire 1998). The following markers were used in this study: arIs37[Pmyo-3::ssGFP; dpy-20] I (Fares and Greenwald 2001a); did-2(ok3325) I (Moerman and Barstead 2008); ego-2(om33) I (Qiao et al. 1995; Liu and Maine 2007); bIs1[vit-2::GFP; rol-6(su1006)] (Grant and Hirsh 1999); unc-36(e251) III (Brenner 1974); cup-5(zu223) III (Hersh et al. 2002); qC1 (Graham and Kimble 1993); mrp-4(cd8) (Schaheen et al. 2006b); and pwIs50[lmp-1::GFP, unc-119(+)] (Treusch et al. 2004). cup-5(zu223) unc-36(e251) worms bearing various transgenes were isolated from qC1-balanced parent heterozygotes; the eggs from these cup-5(zu223) unc-36(e251) homozygous progeny were analyzed in the various assays. The strains used in this study are listed in Table 1.

Table 1 C. elegans strains used in this study.

| Name | Genotype |

|---|---|

| N2 | Wild type |

| GS1912 | dpy-20(e1282); arIs37[Pmyo-3::ssGFP; dpy-20] |

| GS2886 | unc-36(e251); bIs1[vit-2::GFP; rol-6(su1006)] |

| NP27 | cup-5(zu223) unc-36(e251)/qC1 |

| NP35 | cup-5(zu223) unc-36(e251)/qC1; arIs37[Pmyo-3::ssGFP; dpy-20] |

| NP283 | mrp-4(cd8); cup-5(zu223) unc-36(e251); arIs37[Pmyo-3::ssGFP; dpy-20] |

| NP612 | mrp-4(cd8); arIs37[Pmyo-3::ssGFP; dpy-20] |

| NP952 | cup-5(zu223) unc-36(e251)/qC1; bIs1[vit-2::GFP; rol-6(su1006)] |

| NP1160 | unc-119(ed3); cdIs146[MRP-4::GFP; unc-119-ttx-3::GFP] |

| NP1301 | cup-5(zu223) unc-36(e251)/qC1; arIs37; unc-119(ed3); pwIs50[LMP-1::GFP, unc-119] |

| NP1332 | unc-119(ed3); cdIs197[DID-2::LINKER::TagRFP(S158T); unc-119-ttx-3::GFP] |

| NP1359 | did-2(ok3325); cdIs197[DID-2::LINKER::TagRFP(S158T); unc-119-ttx-3::GFP] |

| NP1455 | cup-5(zu223) unc-36(e251)/qC1; unc-75(e950) ego-2(om33) arIs37[Pmyo-3::ssGFP; dpy-20] |

| NP1462 | unc-75(e950) ego-2(om33) arIs37[Pmyo-3::ssGFP; dpy-20] |

| NP1490 | unc-119(ed3); cdIs214[DID-2::LINKER::GFP; unc-119] |

| NP1507 | unc-119(ed3); cdIs212[Pelt-2::MRP-4::LINKER::GFP; unc-119] |

| NP1509 | cup-5(zu223) unc-36(e251)/qC1; cdIs214[DID-2::LINKER::GFP; unc-119] |

| NP1515 | unc-119(ed3); cdIs197[DID-2::LINKER::TagRFP(S158T); unc-119-ttx-3::GFP]; cdIs212[Pelt-2::MRP-4::LINKER::GFP; unc-119] |

| NP1521 | cup-5(zu223) unc-36(e251)/qC1; cdIs212[Pelt-2::MRP-4::LINKER::GFP; unc-119] |

| NP1548 | unc-119(ed3); cdIs228[Pelt-2::DID-2; unc-119] |

| NP1561 | cup-5(zu223) unc-36(e251)/qC1; cdIs197(DID-2::LINKER::TagRFP(S158T); unc-119-ttx-3::GFP); cdIs212[Pelt-2::MRP-4::LINKER::GFP; unc-119] |

| NP1572 | did-2(ok3325)/hT2; cdIs214[DID-2::LINKER::GFP; unc-119] |

| NP1591 | cup-5(zu223) unc-36(e251)/qC1; cdIs228[Pelt-2::DID-2; unc-119] |

| NP1592 | cup-5(zu223) unc-36(e251)/qC1; cdIs146[MRP-4::GFP; unc-119-ttx-3::GFP] |

| NP1597 | unc-119(ed3); cdIs194[LMP-1::TagRFP(S158T); unc-119-ttx-3::GFP]; cdIs212[Pelt-2::MRP-4::LINKER::GFP; unc-119] |

| NP1602 | cup-5(zu223) unc-36(e251)/qC1; cdIs194[LMP-1::TagRFP(S158T); unc-119-ttx-3::GFP]; cdIs212[Pelt-2::MRP-4::LINKER::GFP; unc-119] |

| NP1684 | cdIs243[Pelt-2::GFP; HYGR] |

| NP1687 | cup-5(zu223) unc-36(e251)/qC1; cdIs243[Pelt-2::GFP; HYGR] |

| NP1768 | cdIs212[Pelt-2::MRP-4::LINKER::GFP; unc-119]; cdEx181[Pelt-2::GFP::TagRFP(S158T)::RBB-11.1; HYGR] |

| NP1779 | cup-5(zu223) unc-36(e251)/qC1; cdIs212[Pelt-2::MRP-4::LINKER::GFP; unc-119]; cdEx181[Pelt-2::GFP::TagRFP(S158T)::RBB-11.1; HYGR] |

| NP1789 | cup-5(zu223) unc-36(e251)/qC1; unc-75(e950) ego-2(om33) arIs37[Pmyo-3::ssGFP; dpy-20]; cdIs212[Pelt-2::MRP-4::linkerGFP; unc-119] |

| NP1790 | unc-75(e950) ego-2(om33) arIs37[Pmyo-3::ssGFP; dpy-20]; cdIs212[Pelt-2::MRP-4::linkerGFP; unc-119] |

| NP1825 | mrp-4(cd8); arIs37; unc-119(ed3); cdIs262[pelt-2::MRP-4 genomic; pmyo-2::GFP; unc-119- Pmyo-2::GFP] |

| NP1829 | cup-5(zu223) unc-36(e251)/qC1; mrp-4(cd8); arIs37; cdIs262[pelt-2::MRP-4 genomic;; unc-119- Pmyo-2::GFP] |

| RT258 | unc-119(ed3); pwIs50[LMP-1::GFP, unc-119] |

The following transgenes were made by the bombardment method (Praitis et al. 2001): cdIs146[MRP-4::GFP; unc-119-ttx-3::GFP]; cdIs194[LMP-1:: LINKER(PGGAGAGGAGAG)::TagRFP(S158T); unc-119-ttx-3::GFP]; cdIs197[DID-2::LINKER(PGGAGAGGAGAG)::TagRFP(S158T); unc-119-ttx-3::GFP]; cdIs212[Pelt-2::MRP-4::LINKER(PGGAGAGGAGAG)::GFP; unc-119]; cdIs214[DID-2::LINKER(PGGAGAGGAGAG)::GFP; unc-119]; cdIs228[Pelt-2::DID-2; unc-119]; cdIs243[Pelt-2::GFP]; cdIs262 [Pelt-2::MRP-4]; and cdEx181[Pelt-2::GFP::TagRFP(S158T)::RBB-11.1; HYGR].

Molecular methods

Standard methods were used for the manipulation of recombinant DNA (Sambrook and Russell 2001). PCR was done using the Expand Long Template PCR System (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All other enzymes were from New England Biolabs (Beverly, MA).

Plasmids

Inserts of all plasmids were sequenced to confirm that only the desired changes were introduced. The following plasmids were made and used in this study.

GFP/TagRFP fusion plasmids:

The following GFP/TagRFP fusion plasmids were used: pHD233—MRP-4 fused to GFP(S65T) expressed under the control of the mrp-4 promoter; pHD499—LMP-1 fused to TagRFP(S158T) with an unstructured linker between the two genes and expressed under the control of the lmp-1 promoter; pHD502—DID-2 fused to TagRFP(S158T) with an unstructured linker between the two genes and expressed under the control of the did-2 promoter; pHD543—GFP expressed under the control of the elt-2 promoter; pHD763—RBB-11.1 fused to TagRFP(S158T) expressed under the control of the elt-2 promoter; pHD774—DID-2 fused to GFP(S65T) with an unstructured linker between the two genes and expressed under the control of the did-2 promoter; pHD782—MRP-4 fused to GFP(S65T) with an unstructured linker between the two genes and expressed under the control of the elt-2 promoter; and pHD823—DID-2 fused to GFP(S65T) expressed under the control of the elt-2 promoter.

RNAi plasmids used or made with the L4440/pPD129.36 vector:

From the Ahringer RNAi library (Kamath and Ahringer 2003) the following were used: C07G1.5/hgrs-1, C09G12.9/tsg-101, C27F2.5/vps-22, T27F7.1/vps-24, Y34D9A.10/vps-4, F23C8.6/did-2, E01B7.1/usp-50, C56C10.3/vps-32.1, F21G4.2/mrp-4, and W02C12.3/hlh-30.

From the Orfeome RNAi library (Rual et al. 2004) the following were used: C34G6.7/stam1, Y87G2A.10/vps-28, ZC64.3/ceh-18, W02A11.2/vps-25, F17C11.8/vps-36, Y46G5A.12/vps-2, Y65B4A.3/vps-20, F41E6.9/vps-60, T24B8.2, K10C8.3/istr-1, and F37A4.5.

The following were also used: pHD554, which makes double-stranded RNA corresponding to the last 325 bases of did-2 complementary DNA (cDNA); pHD555, which makes double-stranded RNA corresponding to the full 618 bases of did-2 cDNA; pHD556, which makes double-stranded RNA corresponding to the first 316 bases of did-2 cDNA; pHD670, which makes double-stranded RNA corresponding to amino acids 710–1154 of ego-2; pHD687, which makes double-stranded RNA corresponding to full-length R10E12.1b/alx-1b cDNA; pHD758, which makes double-stranded RNA corresponding to amino acids 710–1154 of ego-2 and full-length cDNA of alx-1b; and pHD863, in which MRP-4 is expressed under the control of the elt-2 promoter.

Plasmid sequences and details on how these plasmids were constructed are available upon request.

Sequence comparison

The DID-2/Did2p/CHMP1b sequence comparison was generated using Clustal Omega (Goujon et al. 2010; Sievers et al. 2011).

Measuring embryonic viability

Adult worms were allowed to lay eggs overnight on NGM plates at 20° (Brenner 1974). The adults were then removed, and the percentage of eggs that hatched and developed normally was calculated. Each viability measurement consists of at least three experiments and the results show the average of these experiments.

Confocal microscopy

Embryos and adults were placed on a 2.2% agarose pad with 1 mM Levamisole or 9 mM Levamisole, respectively, and images were taken using a Zeiss LSM 510 Meta confocal microscope or a Zeiss 510 Meta confocal microscope, using a 63× lens, an argon 488-nm laser for excitation of the GFP, and a helium neon 543-nm laser for excitation of the RFP. For intensity and compartment size measurements, exposure settings for each assay were set using the wild type or wild-type control RNAi strain and were kept the same for all embryos in the assay. Control worms were always included to ensure that signals did not correspond to autofluorescence or to bleed-through from the other fluorophore. Images were taken of embryos that were between the “comma” and the “1.5-fold” stages of embryonic development because these are the first embryonic stages that show the lysosomal defect in the absence of CUP-5 (Schaheen et al. 2006a).

Measurement of intensity and compartment size in embryos

For RNAi experiments, the adult hermaphrodites were placed on the RNAi bacteria, and their laid embryos were analyzed. Measurements of the intensities of GFP and sizes of compartments were done using Metamorph (Sunnyvale, CA) on images that were not modified.

Measurements were made of the sizes and intensities of all VIT-2::GFP-containing compartments within a selected area (213.42 ± 3.28 µm2) at the base of the intestine. At least 120 discrete intracellular structures from four to eight embryos for each strain and RNAi were used in the measurements.

Pdid-2::DID-2::GFP intensity measurements (total, membrane, cytoplasmic) were taken from a selected area (148.19 ± 2.57 µm2) at the base of the intestine. Twenty to 25 embryos were imaged for each strain. The integrated density (density divided by area) of DID-2::GFP punctate (membrane) and diffuse (cytoplasmic) regions was determined. At least 100 discrete intracellular structures from each strain were used in the measurements. Four randomly chosen diffuse spots were chosen from each area for the DID-2::GFP cytoplasmic measurements.

For Pelt-2::DID-2::GFP intensity measurements, 13–14 embryos were imaged for each strain, and the integrated density (density divided by intestine size) was determined for each embryo.

For Pmrp-4::MRP-4::GFP intensity measurements, a z-stack was taken of each embryo (14 embryos imaged for each strain), and the average of the integrated values of all MRP-4::GFP compartments in the intestine from eight layers was determined for each embryo.

For Pelt-2::MRP-4::GFP intensity measurements, 20–25 embryos were imaged for each strain, and the average of the integrated values of all MRP-4::GFP compartments in the intestine was determined for each embryo.

For the HLH-30 suppression intensity measurements (Pdid-2::DID-2::GFP and Pmrp-4::MRP-4::GFP), seven to eight embryos were imaged for each strain, and the average level of each DID-2::GFP/MRP-4::GFP compartment was determined. At least 35 discrete intracellular structures from each strain and RNAi were used in the measurements.

Measurement of lysosomal size and degradation in adults

Hermaphrodites were allowed to lay eggs at 20°. Eggs and worms were collected off the plates in M9 buffer (22 mM KH2PO4, 43 mM Na2HPO4, 86 mM NaCl, and 1 mM MgSO4) and treated with bleach solution (1% NaClO, 1 M NaOH) to dissolve bacteria and worms and isolate the eggs. The embryos were then washed with M9 buffer and placed on NGM plates lacking OP50 bacteria. The next day, the arrested L1 larvae were transferred to plates with RNAi bacteria, and the worms were imaged when they became adults: cup-5(zu223) unc-36(e251) worms were imaged from the cup-5(zu223) unc-36(e251)/qC1 population. To distinguish between LMP-1::GFP compartments and gut granules found in the intestine, both the argon 488-nm laser for GFP excitation and the helium neon 543-nm laser for RFP excitation were used. The autofluorescent gut granules are excited by both lasers while the LMP-1::GFP compartments are excited only by the argon 488-nm laser. Around four adults were imaged for each strain, and the average level of 10 LMP-1::GFP compartments was determined for each strain. A total of at least 30 discrete LMP-1::GFP compartments was determined from each strain and RNAi.

Immunofluorescence

Embryos laid at 20° and expressing both fusion proteins were fixed on slides for 10 min at −20° with 100% methanol and then for 10 min at −20° with 100% acetone. Samples were then washed twice with PBSTw buffer (1× PBS with 0.1% Tween-20) and then placed in Btw buffer (1× PBS, 1% BSA, 0.1% Tween-20) for 2 hr at 4°. A solution containing primary antibodies diluted in Btw buffer was then added, and the samples were left overnight at 4°. Samples were then washed three times with PBSTw buffer and incubated in a Btw solution containing Cy2- and/or Cy3-labeled secondary antibodies for 2 hr at room temperature in the dark, followed by three washes with PBSTw buffer and imaging. For colocalization studies, the same procedure was performed on embryos expressing only MRP-4::GFP or DID-2::TagRFP as a control for nonspecific binding of antibodies.

Measurement of percentage of colocalization/overlap

The percentage of overlap for MRP::GFP and DID-2::TagRFP in the embryo intestine was calculated using “Just Another Colocalization Plugin” from ImageJ (JACoP; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) (Schneider et al. 2012). The values for the Manders’ overlap coefficient M1 were recorded and converted to percentages for the percentage overlap measurement. Eight to 10 embryos were analyzed for each strain.

For measurement of the percentage of colocalization of MRP-4::GFP and LMP-1::TagRFP in the embryo intestine, a z-stack was taken of each embryo (eight to nine embryos for each strain), and the average of the M1 coefficients (calculated by JACoP) from four layers was taken for each embryo. These values were recorded and converted to percentages for the percentage of colocalization.

For measurement of the percentage of colocalization of MRP-4::GFP and LMP-1::TagRFP in the embryo intestine after RNAi of various genes, a z-stack was taken of each embryo (four to seven embryos for each strain and RNAi), and the average of the M1 coefficients (calculated by JACoP) from four layers was taken for each embryo. These values were recorded and converted to percentages for the percentage of colocalization.

For measurement of the percentage of colocalization of MRP-4::GFP and RBB-11.1::TagRFP in the embryo intestine, the number of MRP-4::GFP compartments that also had RBB-11.1::TagRFP were divided by the total number of MRP-4::GFP compartments. Seven to eight embryos were analyzed for each strain.

For measurement of the percentage of colocalization of MRP-4::GFP and RBB-11.1::TagRFP in the embryo intestine after RNAi of various genes, the number of MRP-4::GFP compartments that also had RBB-11.1::TagRFP were divided by the total number of MRP-4::GFP compartments. Four to eight embryos were analyzed for each strain.

qRT-PCR

Hermaphrodites were allowed to lay eggs at 20°. Eggs and worms were collected off the plates in M9 buffer and treated with bleach solution to dissolve bacteria and worms and isolate the viable eggs. The embryos were then washed three times with M9 buffer and lysed in 0.35 ml of ice-cold Qiagen RNeasy buffer RLT (Qiagen, Germantown, MD) using the Bioruptor Standard sonicator (high power, 15 sec ON/60 sec OFF, eight cycles) (Diagenode, Denville, NJ). Total RNA was isolated using the Qiagen RNeasy kit followed by DNase I digestion (ThermoFisher Scientific, Rockford, IL). RNA concentration was determined using a NanoDropxz UV Spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE) before and after DNase 1 digestion. A total of 500 ng of RNA was used to perform oligo(dT) cDNA synthesis with the Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (ThermoFisher Scientific). Quantitative PCR was conducted using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix and an ABI 7300 Real Time PCR System (ThermoFisher Scientific). Raw cycle threshold (Ct) values for mrp-4 were normalized to elt-2. Fold changes were calculated using standard ΔCt methods (Pfaffl 2001). Primers for mrp-4 and elt-2 were designed to span exon/exon junctions to further reduce the chances of genomic DNA amplification. The following primers were used for qRT-PCR: mrp-4 forward and reverse—GACCATTCGAGAGGAGTTTGC and GCTGAGAAGATTGGCAGGAC; and elt-2 forward and reverse—TGCCGACTTGTATCCCGTTTC and ACTTGGATGTTATCGGCAGGTC. RNA isolation from embryos and qRT-PCR was independently done three times for each stain.

DID-2 and MRP-4 necessity assays

RNAi conditions that reduced DID-2::GFP/MRP-4::GFP levels in cup-5(zu223) to wild-type levels were determined by making dilutions of control/pPD129.36 RNAi with varying amounts of did-2 RNAi or mrp-4 RNAi feeding bacteria. To measure the DID-2::GFP/MRP-4::GFP levels corresponding to each dilution, seven to nine embryos were imaged for each strain and dilution. The average level of each DID-2::GFP/MRP-4::GFP compartment was determined. At least 25 discrete intracellular structures from each strain and RNAi were used in the measurements. The dilution where the average level of all the DID-2::GFP/MRP-4::GFP compartments measured in cup-5(zu223) was not statistically different from the average level of DID-2::GFP/MRP4::GFP compartments in wild type was chosen. Viability tests to measure embryonic viability were concurrently done with the imaging such that RNAi’s done for the imaging were done side-by-side with the RNAi’s for viability tests.

Western analysis

Adult wild-type and cup-5(zu223) hermaphrodites were allowed to lay eggs for 14 hr at 20° to minimize the accumulation of dead embryos laid by cup-5(zu223) homozygous parents. Eggs and worms were collected off the plates in M9 buffer and treated with bleach solution to dissolve bacteria and worms and isolate the viable eggs. The embryos were then washed with ddH2O and lysed for Western analysis.

Pelt-2::GFP Western:

After isolation, embryos were suspended in 1× Western Sample Buffer [50 mM Tris, pH 6.8, 10% glycerol, 4% SDS, 10 mM DTT; 1 tablet of complete inhibitor (Life Sciences, Indianapolis) per 1 ml of buffer]. The suspended embryos were freeze-thawed twice (frozen in liquid nitrogen and thawed at 68°) and then boiled for 8 min. Following determination of sample concentrations using Spectra Max 250 (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA), bromophenol blue was added, and same amounts of total protein of the wild type and cup-5(zu223) samples were used for the Western blot.

Pmrp-4::MRP-4::GFP and Pdid-2::DID-2::GFP Western:

After isolation, embryos were suspended in Urea/SDS/NP-40 buffer (4% SDS, 1% NP-40, 5% 2-mercaptoethanol, 6 M Urea, 10 mM DTT, 10% glycerol, 0.002% bromophenol blue, 0.05 M Tris–HCl; 1 tablet of complete inhibitor per 1 ml of buffer). The suspended embryos were frozen in liquid nitrogen, thawed, and sonicated using the Bioruptor Standard sonicator (high power for 15 min, 30 sec ON/30 sec OFF). The samples were then left at 37° for 5 min and spun down at 16,000 × g for 10 min. Ten microliters of each sample wasloaded for Western analysis.

Pelt-2::DID-2::GFP Western and Pelt-2::MRP-4::GFP Western:

After isolation, embryos were suspended in 1× RIPA Buffer (50 mM Tris–HCI, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% SDS, 0.42 mg/ml sodium fluoride, 0.368 mg/ml sodium orthovanadate, 12.1 µg/ml ammonium molybdate, 2.4 mM MG132, 2.5 mg/ml N-ethylmaleimide; 1 tablet of complete inhibitor per 1 ml of buffer). The suspended embryos were frozen in liquid nitrogen, thawed on ice, and sonicated using the Bioruptor Standard sonicator (high power for 5 min, 30 sec ON/30 sec OFF). Following determination of sample concentrations using Spectra Max 250, 5× Western Sample Buffer was added to the samples. The samples were then put at 70° for 10 min and spun-down at 16,000 × g for 10 min. The same amounts of total protein of the wild-type and cup-5(zu223) samples were used for the Western blot.

The intensities of the bands were determined using ImageJ. RME-1 was used as a loading control and to normalize values between wild type and cup-5(zu223) samples.

DID-2::GFP membrane fractionation

Adult wild-type and cup-5(zu223) hermaphrodites were allowed to lay eggs for 14 hr at 20°. Eggs and worms were treated with bleach, and following washes with M9 buffer, the isolated eggs were resuspended in 0.3 ml of membrane lysis buffer (0.2 M Sorbitol, 50 mM KOAc, 2 mM EDTA, 20 mM HEPES–KOH, 1 mM DTT, pH 6.8; 1 tablet of complete inhibitor per 1 ml of buffer). The embryos were then lysed using the Bioruptor Standard sonicator (1 sec at high power followed by 5 sec at low power). The sample was spun-down at 3400 × g for 15 min at 4° to remove intact embryos that had not lysed. and the supernatant was preserved for membrane fractionation.

The supernatant was extracted and spun-down at 200,000 × g for 60 min at 4°. The pellet was kept as the membrane fraction and was resuspended in 200 µl of 1× Laemmli Buffer–Urea (8% SDS, 2% NP-40, 10% 2-mercaptoethanol, 6 M Urea, 20 mM DTT, 20% glycerol, 0.004% bromophenol blue, 0.1 M Tris–HCl; 1 tablet of complete inhibitor per 1 ml of buffer) and left at 37° for 40 min with occasional mixing by pipetting. The supernatant from the 200,000 × g centrifugation represents the cytosolic fraction and was concentrated using a MWCO 3000 microcon (Millipore, Billerica, MA) at 4°. The final volume of the supernatant sample was adjusted to 200 µl in 1× Laemmli buffer–urea, and the sample was incubated at 37° for 10 min. Equal volumes of supernatant and pellet were used for Western analysis.

MRP-4::GFP ubiquitination assay plus or minus RNAi

A total of 1000 adult wild-type, unc-75(e950) ego-2(om33) arIs37[Pmyo-3::ssGFP; dpy-20], cup-5(zu223), or cup-5(zu223); unc-75(e950) ego-2(om33) arIs37[Pmyo-3::ssGFP; dpy-20] hermaphrodites carrying the Pelt-2::MRP-4::GFP transgene were allowed to lay eggs for 14 hr at 20°. Eggs and worms were treated with bleach solution, and following washes with M9 buffer, the isolate eggs were resuspended in 0.3 ml of ice-cold 1× RIPA Buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% SDS, 0.42 mg/ml sodium fluoride, 0.368 mg/ml sodium orthovanadate, 12.1 µg/ml ammonium molybdate, 2.4 mM MG132, 2.5 mg/ml N-ethylmaleimide; 1 tablet of complete inhibitor per 1 ml of buffer). The embryos were lysed using the Bioruptor Standard sonicator (high power for 5 min, 30 sec ON/30 sec OFF). The sample was spun-down to remove intact eggs, and the supernatant was transferred to a new tube. Thirty microliters of the supernatant was added to 30 µl of 2× Western Sample Buffer (100 mM Tris, pH 6.8, 20% glycerol, 8% SDS, 20 mM DTT, 20% bromophenol blue; 1 tablet of complete inhibitor per 1 ml of buffer); this was the total protein sample. The remainder of the sample was used for immunoprecipitation.

Immunoprecipitation was done using 20 µl of Sepharose-conjugated anti-GFP beads (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) in Pierce Centrifuge Columns (Rockford, IL). The Sepharose-conjugated anti-GFP beads in 700 µl of 1× RIPA Buffer were added to the columns and then centrifuged at 2875 × g for 1 min. The columns were washed two more times with 1× RIPA Buffer. Following the last spin, the supernatant was added to the column and left to mix overnight at 4°. The beads were washed three times with 700 µl of 1× RIPA Buffer (using 1 min 2875 × g centrifugation). Immunoprecipitates were eluted using 100 µl of 2× Western Buffer without DTT preheated to 95°. Following elution, 2 µl of 1 M DTT was added to samples that were incubated at 70° for 30 min.

Antibodies and Western detection

Antibodies used in this study were the following: chicken anti-GFP (Abcam); mouse anti-Ubiquitin P4D1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX); mouse anti-Ubiquitin FK1 (Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY); mouse anti-RME-1 (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, Iowa City, IA) (Hadwiger et al. 2010); mouse anti-LMP-1 (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank) (Hadwiger et al. 2010); rabbit anti-TagRFP (Abcam); donkey anti-rabbit-IgG-Cy3 (Jackson ImunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA); donkey anti-Chicken-IgY-FITC (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories); donkey anti-chicken IgG-HRP (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories); and goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories).

Western detection was done using the SuperSignal West Dura kit (ThermoFisher Scientific).

Statistical methods

The Student’s t-test was used to compare average measurements from two samples using a two-tailed distribution (tails = 2) and a two-sample unequal variance (type = 2). Unless otherwise specified, all error bars represent the standard deviation.

Data availability

All data and reagents are available upon request.

Results

Identification of an ESCRT-associated protein suppressor of cup-5(null) lethality

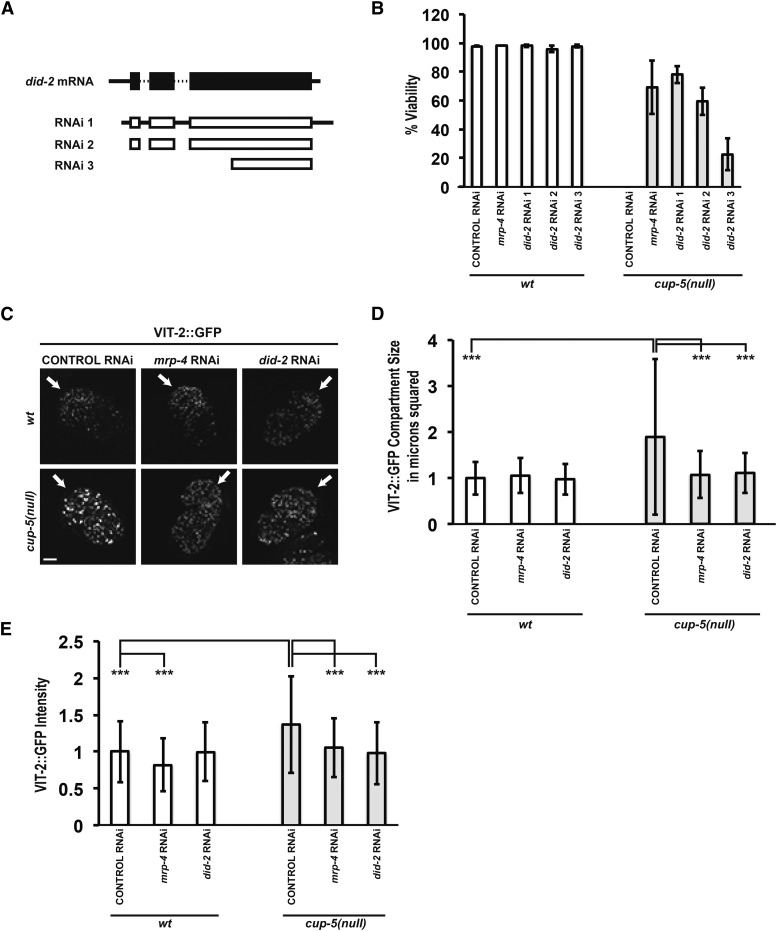

To decipher pathways that lead from loss of CUP-5 to developing intestinal cell death, we began a genome-wide RNA interference (RNAi) feeding screen for suppressors of cup-5(null) embryonic lethality (Kamath and Ahringer 2003). We identified did-2/phi-24/F23C8.6 as a strong suppressor of cup-5(null). While 0% of eggs laid by cup-5(null) worms hatched after control RNAi, 79 ± 6% of eggs laid by cup-5(null) worms hatched after did-2 RNAi; viable worms grew to adulthood within 2–3 days of hatching, similar to wild-type worms (RNAi 1 in Figure 1, A and B). This strong suppression of cup-5(null) lethality by did-2 RNAi is similar to the suppression of cup-5(null) lethality by the mrp-4 null allele or mrp-4 RNAi (Figure 1B) (Schaheen et al. 2006b). DID-2 is the C. elegans homolog of S. cerevisiae Did2p (37.6% identical) and human CHMP1b (53.2% identical) (Supporting Information, Figure S1A).

Figure 1.

Suppression of cup-5(null) defects by RNAi of did-2. (A) Structure of did-2 mRNA (solid black boxes indicate translated regions, solid lines are 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions, and dashed lines are introns) and targeted areas by did-2 RNAi constructs (RNAi 1–3). (B) Percentage of viable worms laid by wild-type or cup-5(null) hermaphrodites after the indicated RNAi’s. (C) Confocal images of comma to 1.5-fold stage embryos laid by wild-type or cup-5(null) hermaphrodites carrying the VIT-2::GFP transgene after the indicated RNAi’s. All images were taken at the same exposure and magnification. Arrows indicate intestinal cells. (D) Quantitation of surface area of VIT-2::GFP compartments in intestinal cells shown in C. (E) Quantitation of the intensity of the VIT-2::GFP compartments in intestinal cells shown in C. Three asterisks indicate P < 0.0005. Measurements were normalized to 1 in D and E using the wild-type control RNAi values. Bars in whole-embryo images: 10 µm.

We could not use the did-2(ok3325) null allele to test for suppression of cup-5(null) lethality because homozygous did-2(ok3325) is embryonically lethal (Moerman and Barstead 2008). Although the genomic did-2 RNAi feeding clone included an insert that does not have predicted secondary targets, we designed two other RNAi feeding constructs to confirm that the suppression was due to reduction of did-2 levels. These two RNAi clones also suppressed cup-5(null) lethality, albeit with different efficiencies as has been seen in many other genes (Figure 1, A and B). We used the did-2 RNAi 1 clone for all of the future experiments.

Reducing levels of did-2 rescues the lysosomal degradation defects of cup-5(null)

cup-5(null) mutants have dysfunctional lysosomes that lead to embryonic lethality and tissue degeneration (Schaheen et al. 2006a; Campbell and Fares 2010). To determine whether DID-2 exerts its effects upstream or downstream of the lysosomal defects found in cup-5(null) mutants, we looked at lysosomal degradation of the yolk protein VIT-2. VIT-2::GFP is endocytosed by oocytes and subsequently degraded primarily by intestinal cells in developing embryos (Grant and Hirsh 1999).

As we had previously shown, VIT-2::GFP accumulates in larger vacuoles in cup-5(null) mutants compared to wild type (Figure 1, C–E) (Schaheen et al. 2006a). While RNAi of did-2 had no significant effect on lysosome size and degradation of VIT-2::GFP in wild-type embryos, RNAi of did-2 in cup-5(null) mutants rescued both the expanded lysosome sizes and the defective degradation of VIT-2::GFP (Figure 1, C–E). This suppression of cup-5(null) lysosomal defects after reducing levels of DID-2 indicates that DID-2 protein function is necessary for the development of lysosomal defects in cup-5(null) embryonic intestinal cells.

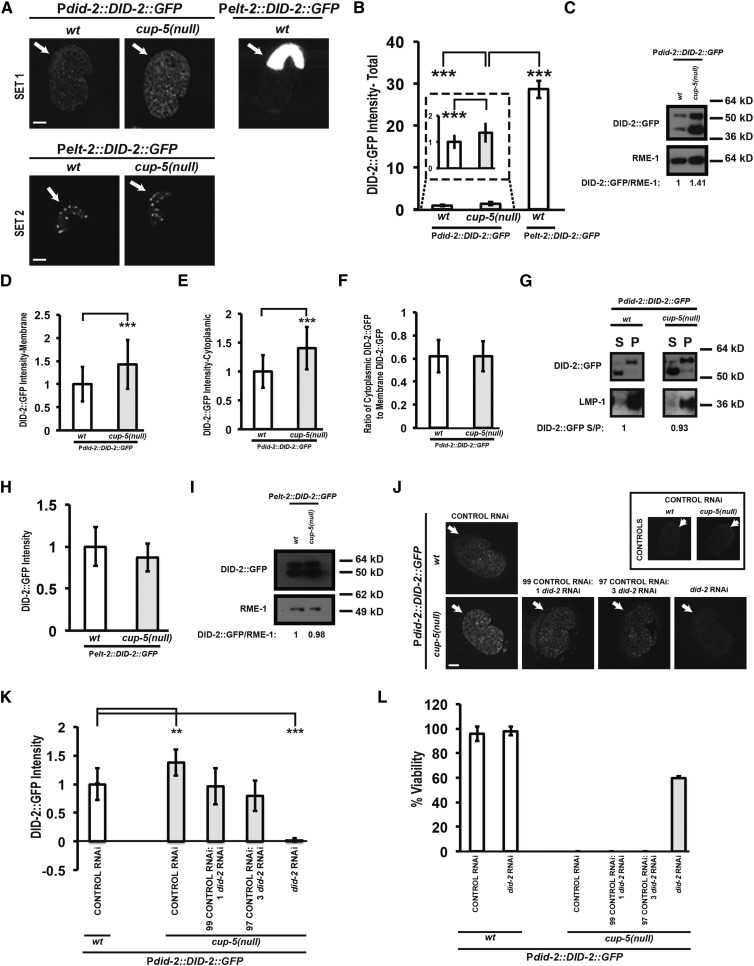

DID-2 protein levels are increased in cup-5(null) mutants

We determined whether alterations to DID-2 levels accounted for the requirement of DID-2 for the lysosomal defects in the absence of CUP-5. We first made transgenic worms that express a functional DID-2::GFP fusion protein under the control of its own did-2 promoter (Figure S1B). DID-2::GFP localizes to the cytoplasm and to endosomal membranes. Analysis of confocal images of developing intestinal cells in embryos showed that total (membrane bound and cytoplasmic) DID-2::GFP levels were increased in cup-5(null) embryos relative to wild-type embryos (Figure 2, A and B). We got similar results using Western analysis on total proteins from mixed-stage embryos (Figure 2C). In these Western blots of total embryonic proteins, DID-2::GFP often appeared as a doublet with a lower band at its expected size of ∼49 kDa and an upper band that is 7–10 kDa larger; the levels of both the lower and the upper bands are proportionally increased in the absence of CUP-5 (Figure 2C). RME-1 was used to normalize loading since RME-1 protein levels are the same in wild-type and cup-5(null) embryos (Figure S2, A–C).

Figure 2.

Characterization of DID-2 protein defects in cup-5(null). (A) Confocal images of 1.5-fold stage embryos laid by wild-type (wt) and cup-5(null) (zu223 allele) hermaphrodites carrying the DID-2::GFP transgene expressed from the did-2 promoter or the elt-2 promoter. All images in set 1 were taken using the same exposure and magnification. All images in set 2 were taken using the same exposure and magnification. Under both of these microscopy conditions, embryos lacking this transgene showed no background fluorescence. Arrows indicate intestinal cells. (B) Quantitation of total DID-2::GFP levels in intestinal cells of wild-type embryos and cup-5(null) embryos expressing the indicated fusion protein shown in A, set 1. DID-2::GFP levels expressed from the elt-2 promoter in wild-type embryos from set 1 is likely higher due to the saturation of the images. (C) Western blot showing DID-2::GFP and RME-1 levels in embryos laid by Pdid-2::DID-2::GFP wild-type or cup-5(null) hermaphrodites. RME-1 was used for normalization. The total of both DID-2::GFP bands was used for the quantitation. (D) Quantitation of membrane-bound DID-2::GFP levels in intestinal cells of Pdid-2::DID-2::GFP wild-type and cup-5(null) embryos hermaphrodites shown in A. (E) Quantitation of cytoplasmic DID-2::GFP in intestinal cells of Pdid-2::DID-2::GFP wild-type and cup-5(null) embryos laid by hermaphrodites shown in A. (F) Quantitation of the ratio of cytoplasmic DID-2::GFP to membrane-bound DID-2::GFP in intestinal cells of Pdid-2::DID-2::GFP wild-type and cup-5(null) embryos laid by hermaphrodites shown in A. (G) Membrane-bound DID-2::GFP (pellet) was separated from cytoplasmic DID-2::GFP (supernatant) in embryos laid by Pdid-2::DID-2::GFP, wild-type, or cup-5(null) hermaphrodites. DID-2::GFP and LMP-1 protein were then detected by Western analysis. DID-2::GFP S/P represents the ratio of cytoplasmic DID-2::GFP to membrane-bound DID-2::GFP; the total of both DID-2::GFP bands was used for the quantitation. LMP-1 protein was used as a control of fractionation. (H) Quantitation of DID-2::GFP levels in intestinal cells of wild-type and cup-5(null) embryos laid by Pelt-2::DID-2::GFP hermaphrodites shown in A, set 2. (I) Western blot showing DID-2::GFP and RME-1 levels in embryos laid by Pelt-2::DID-2::GFP wild-type or cup-5(null) hermaphrodites. Equal amounts of total protein levels were loaded. RME-1 was used for normalization. The total of both DID-2::GFP bands were used for the quantitation. (J) Confocal images of comma to 1.5-fold stage embryos laid by Pdid-2::DID-2::GFP wild-type or cup-5(null) hermaphrodites after the indicated RNAi’s. The ratios of control RNAi to did-2 RNAi represent two dilutions of the did-2 RNAi bacterial seeding clone with the control RNAi bacterial seeding clone. All images were taken using the same exposure and magnification. Arrows indicate intestinal cells. The boxed images are autofluorescence controls of embryos that do not carry the Pdid-2::DID-2::GFP transgene. (K) Quantitation of DID-2::GFP intensity in intestinal cells after the indicated RNAi’s of embryos shown in J. (L) Percentage of embryos laid by Pdid-2::DID-2::GFP wild-type or cup-5(null) hermaphrodites that hatched after the indicated RNAi’s shown in J. Two asterisks indicate P < 0.005; three asterisks indicate P < 0.0005. Measurements were normalized to 1 in B, D, E, H, and K using the wild type or wild-type control RNAi values. Bars, 10 µm in all images.

We then asked whether there was more DID-2::GFP being recruited and bound to endosomal membranes in cup-5(null). Quantitation of the confocal images showed that, individually, both cytoplasmic and membrane-bound DID-2::GFP levels are increased in cup-5(null) (Figure 2, A, D, and E). However, there was not a significant difference in the ratio of cytoplasmic DID-2::GFP to membrane-bound DID-2::GFP in wild type (0.62 +/− 0.14) compared to cup-5(null) (0.62 ± 0.13) (Figure 2, A and F). This result was confirmed by membrane fractionation where the ratio of DID-2::GFP found in the supernatant (cytoplasmic) to DID-2::GFP in the pellet (membrane bound) was similar in wild-type and cup-5(null) embryos (Figure 2G). In addition, the larger sized DID-2::GFP band appeared to be the predominant membrane-bound form of DID-2::GFP in both wild type and cup-5(null) embryos (Figure 2G). C. elegans LMP-1 is homologous to human Lysosomal-Associated Membrane Protein 1 (LAMP1) and was used to test for proper partitioning of membrane and cytosolic fractions (Figure 2G) (Kostich et al. 2000).

To determine whether increased DID-2::GFP levels in the absence of CUP-5 is due to changes in DID-2 protein stability, we expressed DID-2::GFP under the control of the intestine-specific elt-2 promoter (Fukushige et al. 1998); elt-2 promoter activity is unaffected by the loss of CUP-5 (Figure S2, D–F). If the increase in DID-2::GFP (expressed from the did-2 promoter) levels in the absence of CUP-5 is due to a defect in DID-2::GFP degradation, we would expect to see the same increase in DID-2::GFP (expressed from the elt-2 promoter) levels. However, we saw that expression of DID-2::GFP from the elt-2 promoter resulted in similar expression levels between wild-type and cup-5(null) embryos using confocal microscopy and Western analysis (Figure 2, A, H, and I). This indicates that increased DID-2 levels in the absence of CUP-5 are not due to altered degradation of DID-2 protein.

This increase in DID-2 levels is consistent with previous in vitro studies that showed that MLIV fibroblasts have altered gene expression, including differential regulation of genes functioning in endosome/lysosome trafficking and lysosome biogenesis (Bozzato et al. 2008). The transcription factor EB was found as a key regulator of this differential expression; under conditions of lysosomal dysfunction, transcription factor EB translocates to the nucleus and changes the gene expression profile of lysosomal genes, including MCOLN1 (Sardiello et al. 2009). We used HLH-30, the C. elegans ortholog of TFEB, to determine whether the increase in DID-2 protein levels was due to TFEB-mediated transcriptional activation (Lapierre et al. 2013). RNAi of hlh-30 did not affect the increase of DID-2 levels in cup-5(null) embryos, indicating that the increase in DID-2 protein levels is not due to a TFEB-mediated defect in transcription, but is rather due to defects in messenger RNA (mRNA) processing, degradation, or translation (Figure S3, A and B).

Increased DID-2 levels in cup-5(null) are not sufficient or necessary for cup-5(null) embryonic lethality

To examine the relevance of increased DID-2 levels to cup-5(null) lethality, we asked whether this phenotype was sufficient and/or necessary. The DID-2::GFP expressed from the elt-2 promoter in wild-type embryos is significantly higher than the DID-2::GFP expressed from the did-2 promoter in cup-5(null) embryos (Figure 2, A and B). However, unlike the 100% embryonic lethality of cup-5(null) mutants, embryos laid by Pelt-2::DID-2::GFP wild-type worms are fully viable. This suggests that increased DID-2::GFP levels are not sufficient to cause the embryonic lethality found in cup-5(null). However, the increase in DID-2 levels might still be necessary for cup-5(null) lethality.

We identified the RNAi condition that reduced DID-2 levels in cup-5(null) mutants to those seen in wild-type embryos; this still resulted in 0% viability in cup-5(null) embryos (Figure 2, J–L). Therefore, while increased DID-2 levels is a phenotype seen in the absence of CUP-5, this increase is neither sufficient nor necessary for lethality; the mere presence of DID-2 protein in cells causes cell death in the absence of CUP-5.

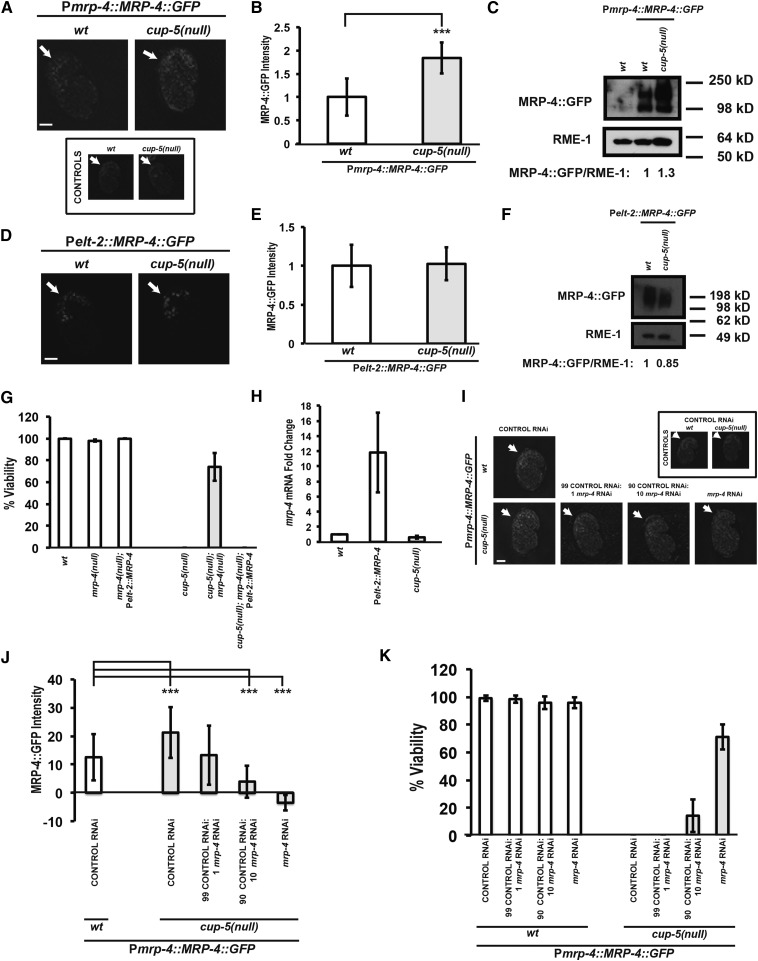

Increased MRP-4 levels in cup-5(null) are not due to a defect in MRP-4 degradation rate

DID-2 is a member of the ESCRT complex that targets integral membrane proteins for lysosomal degradation; one of these candidate proteins is the ABC Transporter MRP-4. We had previously shown that reducing levels of MRP-4 in cup-5(null) rescues the lysosomal defects in developing intestinal cells and embryonic lethality (Figure 1, C–F) (Schaheen et al. 2006b). We had also shown, using a partially functional MRP-4::GFP construct, that MRP-4 levels are elevated in cup-5(null) embryos, which we confirmed with a similar partially functional construct using confocal microscopy and Western analysis (Figure 3, A–C) (Schaheen et al. 2006b).

Figure 3.

Characterization of MRP-4 protein defects in cup-5(null). (A) Confocal images of 1.5-fold stage embryos laid by wild type (wt) and cup-5(null) (zu223 allele) hermaphrodites carrying the MRP-4::GFP transgene expressed from the native mrp-4 promoter. All images were taken using the same exposure and magnification. Arrows indicate intestinal cells. (B) Quantitation of MRP-4::GFP levels in intestinal cells shown in A. Background immunofluorescence values from wild type and cup-5(null) not carrying the MRP-4::GFP transgene were subtracted. (C) Western blot showing MRP-4::GFP and RME-1 levels in embryos laid by Pmrp-4::MRP-4::GFP wild-type or cup-5(null) hermaphrodites. RME-1 was used for normalization. (D) Confocal images of 1.5-fold stage embryos laid by wild-type and cup-5(null) hermaphrodites carrying the MRP-4::GFP transgene expressed from the elt-2 promoter. All images were taken using the same exposure and magnification. Arrows indicate intestinal cells. Under these microscopy conditions, embryos lacking this transgene showed no background fluorescence. (E) Quantitation of MRP-4::GFP levels in intestinal cells shown in D. (F) Western blot showing MRP-4::GFP and RME-1 levels in embryos laid by Pelt-2::MRP-4::GFP wild-type or cup-5(null) hermaphrodites. Equal amounts of total protein levels were loaded. RME-1 was used for normalization. (G) Percentage of viable worms laid by hermaphrodites with the indicated genotypes. (H) Fold-change of mrp-4 mRNA levels in Pelt-2::MRP-4 and cup-5(null) relative to wild-type embryos as determined by qRT-PCR. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. (I) Confocal images of 1.5-fold stage embryos laid by Pmrp-4::MRP-4::GFP wild-type or cup-5(null) hermaphrodites after the indicated RNAi’s. The ratios of control RNAi to mrp-4 RNAi represent two dilutions of the mrp-4 RNAi bacterial seeding clone with the control RNAi bacterial seeding clone. All images were taken using the same exposure and magnification. Arrows indicate intestinal cells. (J) Quantitation of MRP-4::GFP puncta intensity in intestinal cells shown in G. (K) Percentage of embryos laid by Pmrp-4::MRP-4::GFP wild-type or cup-5(null) hermaphrodites that hatched after the indicated RNAi’s shown in G. Three asterisks indicate P < 0.0005. Measurements were normalized to 1 in B, E, and H using the wild type or wild-type control RNAi values. Bars, 10 µm in all images.

We had expected that the increased MRP-4 levels in cup-5(null) were caused by a defect in the rate of MRP-4 degradation because of the identification of DID-2 and its ESCRT functions. However, when we assayed for changes in the stability of MRP-4 protein by expressing MRP-4::GFP under the control of the intestine-specific elt-2 promoter that is unaffected by the loss of CUP-5, we saw that the levels of MRP-4::GFP in wild-type and cup-5(null) embryos did not differ using confocal microscopy and Western analysis (Figure 3, D–F). This indicates that the increased levels of MRP-4 protein in cup-5(null) are not due to a defect in degradation. In addition, although reducing the levels of the C. elegans TFEB ortholog HLH-30 did not suppress the increase in DID-2 protein levels in cup-5(null) embryos, we found that hlh-30 RNAi suppressed the increase in MRP-4 protein levels in cup-5(null) embryos (Figure S3, C and D). This suggests that this increase in MRP-4 levels in the absence of CUP-5 is due to HLH-30-mediated transcription. We next asked whether the MRP-4 increased levels were sufficient or necessary for embryonic lethality in cup-5(null) worms.

MRP-4 protein increased levels in cup-5(null) are not sufficient or necessary for embryonic lethality

While wild-type Pelt-2::MRP-4::GFP embryos have almost seven times increased MRP-4::GFP relative to cup-5(null); Pmrp-4::MRP-4::GFP embryos, we could not use these Pelt-2::MRP-4::GFP strains to assay sufficiency of MRP-4 overexpression to cause embryonic lethality because MRP-4::GFP is partially functional. Therefore, we made another transgenic strain carrying a Pelt-2::MRP-4 transgene that expresses a functional MRP-4 protein because it reverses the suppression of cup-5(null) embryonic lethality by the null allele mrp-4(cd8) (Figure 3G) (Schaheen et al. 2006b). In three independent experiments, quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) showed that mrp-4 mRNA levels in the Pelt-2::MRP-4 strain are 3, 10, and 21 times higher than nontransgenic strains (Figure 3H). Note that we do not see increased mrp-4 RNA levels in cup-5(null) compared to wild type since a 1.3- to 1.7-fold increase seen in MRP-4::GFP protein levels between these two strains is below the sensitivity of qRT-PCR (Figure 3, A–C and H). Embryos laid from Pelt-2::MRP-4 hermaphrodites are 100% viable (Figure 3G). This indicates that increased levels of MRP-4 are not sufficient to cause cup-5(null) lethality.

We then assessed the pertinence of increased MRP-4 protein levels for cup-5(null) embryonic lethality using the approach that we used to study DID-2 necessity. We identified the RNAi conditions that would reduce MRP-4 levels in cup-5(null) mutants to the levels found in wild-type embryos (Figure 3, I and J). Reduction of MRP-4 levels down to the levels seen in wild-type worms still resulted in 0% viability in cup-5(null) embryos (Figure 3, I–K). Indeed, even reducing cup-5(null) MRP-4 levels down to half the amount in wild type gives only a very slight rescue of lethality (Figure 3, I–K). Thus, the increased levels of MRP-4 are not necessary for the lethality, meaning that the presence of wild-type (or lower) levels of MRP-4 protein in cup-5(null) embryos is sufficient to cause embryonic lethality. Since the levels of MRP-4 protein in cup-5(null) are not necessary for lethality, we tested whether did-2 RNAi suppression is mediated by altering the localization of MRP-4 protein.

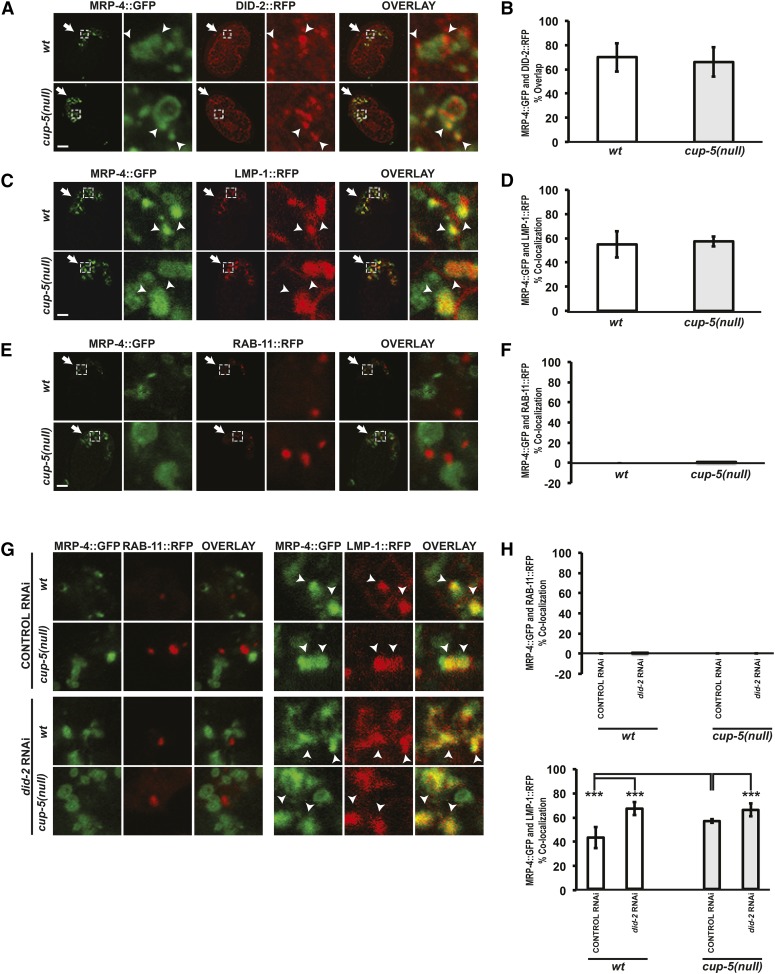

did-2 RNAi suppression of cup-5(null) defects is not caused by altered localization of MRP-4 protein

Immunofluorescence of embryos expressing a functional DID-2::RFP and MRP-4::GFP showed that, while the staining patterns of these two proteins were fairly different, there was still extensive overlap (Figure 4, A and B). MRP-4::GFP stains whole membranes of compartments, while DID-2::RFP appears to stain punctate microdomains on the same membranes or adjacent compartments (Figure 4, A and B). These results indicate that MRP-4 and DID-2 localize close to each other on endosomes/lysosomes, consistent with MRP-4 protein being a substrate for DID-2/ESCRT functions (see below).

Figure 4.

MRP-4 protein localization in wild type and cup-5(null). (A) Confocal images of comma to 1.5-fold stage embryos laid by wild type (wt) or cup-5(null) (zu223 allele) hermaphrodites that were immunostained to detect DID-2::RFP and MRP-4::GFP. Arrows indicate intestinal cells. Arrowheads indicate overlap between DID-2::RFP and MRP-4::GFP. Images to the right of the embryos are magnified images of the regions indicated by the dashed white boxes. (B) Quantitation of DID-2::RFP and MRP-4::GFP percent overlap in intestinal cells shown in A. (C) Confocal images of 1.5-fold stage embryos laid by wild-type or cup-5(null) hermaphrodites expressing MRP-4::GFP and LMP-1::RFP. Arrows indicate intestinal cells. Arrowheads indicate colocalization between MRP-4::GFP and LMP-1::RFP. Images to the right of the embryos are magnified images of the regions indicated by the dashed white boxes. (D) Quantitation of MRP-4::GFP and LMP-1::RFP percentage of colocalization in intestinal cells shown in C. (E) Confocal images of 1.5-fold embryos laid by wild-type or cup-5(null) hermaphrodites expressing MRP-4::GFP and RBB-11.1::RFP. Arrows indicate intestinal cells. Images to the right of the embryos are magnified images of the regions indicated by the dashed white boxes. (F) Quantitation of MRP-4::GFP and RBB-11.1::RFP percentage of colocalization in intestinal cells shown in E. (G) Confocal images of comma to 1.5-fold stage embryos laid by wild-type and cup-5(null) hermaphrodites expressing MRP-4::GFP and LMP-1::RFP or RBB-11.1::RFP after the indicated RNAi’s. Only the magnified images are shown. Arrowheads indicate colocalization. (H) Quantitation of MRP-4::GFP and LMP-1::RFP percentage of colocalization and MRP-4::GFP and RBB-11.1::RFP percentage of colocalization in intestinal cells shown in G. Three asterisks indicate P < 0.0005. Bars in whole-embryo images: 10 µm.

Reducing levels of did-2 might rescue cup-5(null) lethality by shuttling MRP-4 protein away from late endosomes/lysosomes where MRP-4’s increased transport activity is damaging to these compartments. We therefore first assayed MRP-4 protein localization in the endo-lysosomal pathway in wild-type and cup-5(null) embryos. MRP-4::GFP colocalizes with LMP-1::RFP, a lysosomal membrane marker in wild type and cup-5(null), with no difference in percentage of colocalization of the two proteins between wild type and cup-5(null) (Figure 4, C and D) (Campbell and Fares 2010). Thus, MRP-4 protein trafficks through the endo-lysosomal system. We then assayed MRP-4 protein trafficking in the recycling pathway by looking at its localization with RBB-11.1::RFP, a marker for recycling endosomes. We saw no MRP-4 protein colocalized with the RBB-11.1 recycling endosomes in wild-type and cup-5(null) embryos, indicating that MRP-4 does not typically get trafficked through the recycling pathway (Figure 4, E and F).

Given MRP-4 protein’s presence in the endo-lysosomal pathway and absence in the recycling pathway, we asked whether RNAi of did-2 rescued cup-5(null) lethality by trafficking MRP-4 to the recycling pathway or at the least away from lysosomes where its activity is damaging. RNAi of did-2 still resulted in no colocalization between MRP-4::GFP and RBB-11.1::RFP in wild type and cup-5(null), indicating that did-2 RNAi rescue was not due to moving MRP-4 protein to the recycling pathway (Figure 4, G and H). Additionally, RNAi of did-2 did not result in less MRP-4 protein trafficking through the endo-lysosomal system since we did not see lower colocalization between MRP-4::GFP and LMP-1::RFP in cup-5(null) after RNAi of did-2; in fact, there was a slight increase in colocalization between the proteins (Figure 4, G and H). This indicates that did-2 RNAi does not rescue cup-5(null) defects by altering the endo-lysosomal localization of MRP-4 protein. We then assayed whether cup-5(null) lethality and did-2 RNAi rescue was due to alterations in MRP-4 protein.

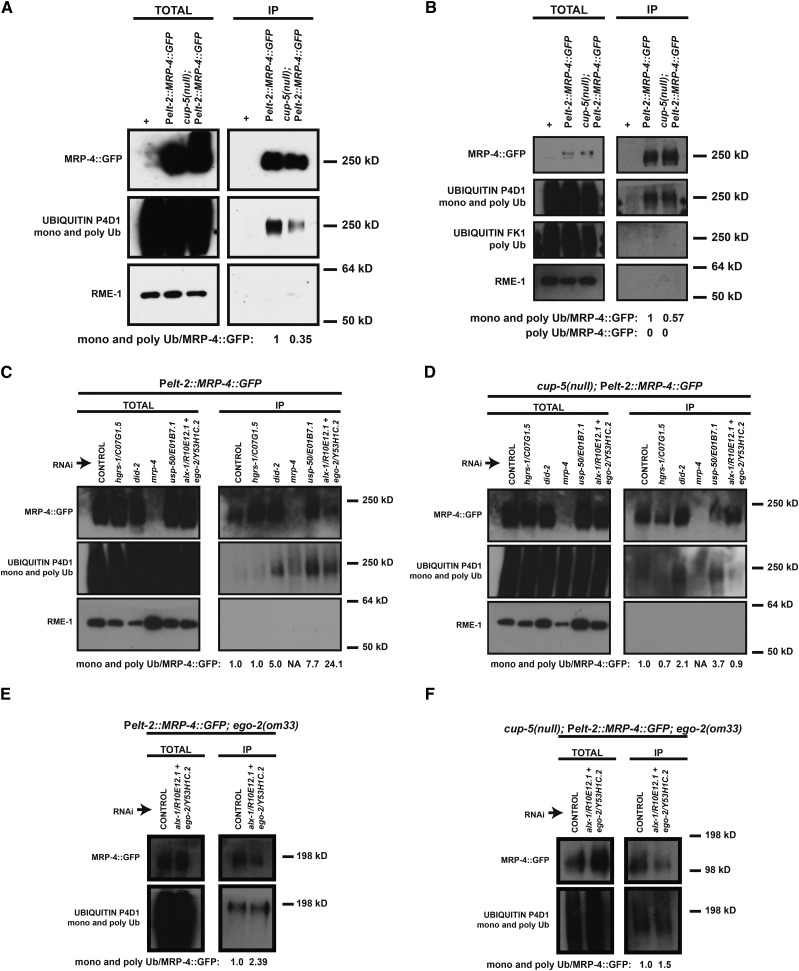

MRP-4 protein is hypo-ubiquitinated in cup-5(null)

DID-2 is a member of the ESCRT-associated complex that is required for the de-ubiquitination of integral membrane proteins prior to the completion of the internalization of these integral membrane proteins in intraluminal vesicles. We therefore assayed whether the loss of CUP-5 resulted in perturbations to MRP-4 ubiquitination. We immunoprecipitated MRP-4::GFP out of total protein isolates from wild-type and cup-5(null) embryos and determined the fraction of both mono- and poly-ubiquitinated MRP-4::GFP in Western blots using the P4D1 antibody. We found that MRP-4 protein is hypo-ubiquitinated in cup-5(null) embryos; at steady state, MRP-4 in cup-5(null) shows a significant decrease in ubiquitination to ∼35–57% of the levels seen in wild-type embryos (Figure 5, A and B).

Figure 5.

MRP-4 protein ubiquitination in wild type and cup-5(null). (A) Western blots probing for MRP-4::GFP, ubiquitin, and RME-1 protein in embryos laid by Pelt-2::MRP-4::GFP, wild-type, or cup-5(null) hermaphrodites. (Left) Total protein isolates. (Right) Total protein isolates after immunoprecipitation of MRP-4::GFP. The P4D1 antibody was used to detect ubiquitin; this antibody detects both mono- and poly-ubiquitination. Ub/MRP-4::GFP represents the fraction of MRP-4 that is ubiquitinated. The plus sign (+) indicates control wild-type worms that do not carry the Pelt-2::MRP-4::GFP transgene. (B) Western blots probing for MRP-4::GFP, ubiquitin, and RME-1 protein in embryos laid by Pelt-2::MRP-4::GFP, wild-type, or cup-5(null) hermaphrodites. (Left) Total protein isolates. (Right) Total protein isolates after immunoprecipitation of MRP-4::GFP. In addition to the P4D1 antibody, the FK1 antibody was used to specifically detect poly-ubiquitin. Ub/MRP-4::GFP represents the fraction of MRP-4 that is ubiquitinated. The plus sign (+) indicates control wild-type worms that do not carry the Pelt-2::MRP-4::GFP transgene. (C) Western blots probing for MRP-4::GFP, ubiquitin, and RME-1 protein in embryos laid by Pelt-2::MRP-4::GFP wild-type hermaphrodites after the indicated RNAi’s. (Left) Total protein isolates. (Right) Total protein isolates after immunoprecipitation of MRP-4::GFP. The P4D1 antibody was used to detect ubiquitin; this antibody detects both mono- and poly-ubiquitination. Ub/MRP-4::GFP represents the fraction of MRP-4::GFP that is ubiquitinated. (D) Western blots probing for MRP-4::GFP, ubiquitin, and RME-1 protein in embryos laid by cup-5(null); Pelt-2::MRP-4::GFP hermaphrodites after the indicated RNAi’s. (Left) Total protein isolates. (Right) Total protein isolates after immunoprecipitation of MRP-4::GFP. Ub/MRP-4::GFP represents the fraction of MRP-4::GFP that is ubiquitinated. (E) Western blots probing for MRP-4::GFP and ubiquitin in embryos laid by ego-2(om33); Pelt-2::MRP-4::GFP hermaphrodites after the indicated RNAi’s. (Left) Total protein isolates. (Right) Total protein isolates after immunoprecipitation of MRP-4::GFP. Ub/MRP-4::GFP represents the fraction of MRP-4::GFP that is ubiquitinated. (F) Western blots probing for MRP-4::GFP and ubiquitin in embryos laid by cup-5(null); ego-2(om33); Pelt-2::MRP-4::GFP hermaphrodites after the indicated RNAi’s. (Left) Total protein isolates. (Right) Total protein isolates after immunoprecipitation of MRP-4::GFP. Ub/MRP-4::GFP represents the fraction of MRP-4::GFP that is ubiquitinated. Measurements were normalized to 1 in A–F using the wild type, wild-type control RNAi, or cup-5(null) control RNAi Ub/MRP-4::GFP values. RME-1 was used to confirm MRP-4::GFP enrichment following immunoprecipitation.

Mono-ubiquitination is the signal for cargo entry into the ESCRT pathway (Katzmann et al. 2001; Reggiori and Pelham 2001). We used the FK1 antibody, which detects only poly-ubiquitin to assess whether MRP-4 protein is mono- or poly-ubiquitinated. Similar to the P4D1 antibody, the FK1 antibody also detects many proteins that are ubiquitinated in total embryonic lysates (Figure 5B). However, unlike P4D1, FK1 did not detect poly-ubiquitinated immunoprecipitated MRP-4::GFP in wild-type or cup-5(null) embryos (Figure 5B). This suggests that MRP-4 protein is mono-ubiquitinated at a lower level in cup-5(null) embryos. Therefore, we assayed whether the cup-5(null) hypo-ubiquitination was dependent on the presence of DID-2 protein.

Hypo-ubiquitination in cup-5(null) is rescued by reducing levels of did-2

We assayed MRP-4 ubiquitination in wild-type and cup-5(null) embryos after RNAi of did-2. We saw a fivefold increase in MRP-4 ubiquitination at steady state after did-2 RNAi in wild-type embryos (Figure 5C). This is consistent with DID-2’s function: recruitment of the de-ubiquitinating enzyme to endosomal membranes where it can act on MRP-4 (Row et al. 2007). Similarly, there was an increase in MRP-4 ubiquitination at steady state in cup-5(null) embryos after RNAi of did-2 compared to cup-5(null) embryos after the control RNAi (Figure 5D). This increase indicates that the hypo-ubiquitination of MRP-4 in cup-5(null) developing intestinal cells in embryos is dependent on DID-2 protein and suggests the involvement of other ESCRT-associated proteins in this MRP-4 ubiquitination defect.

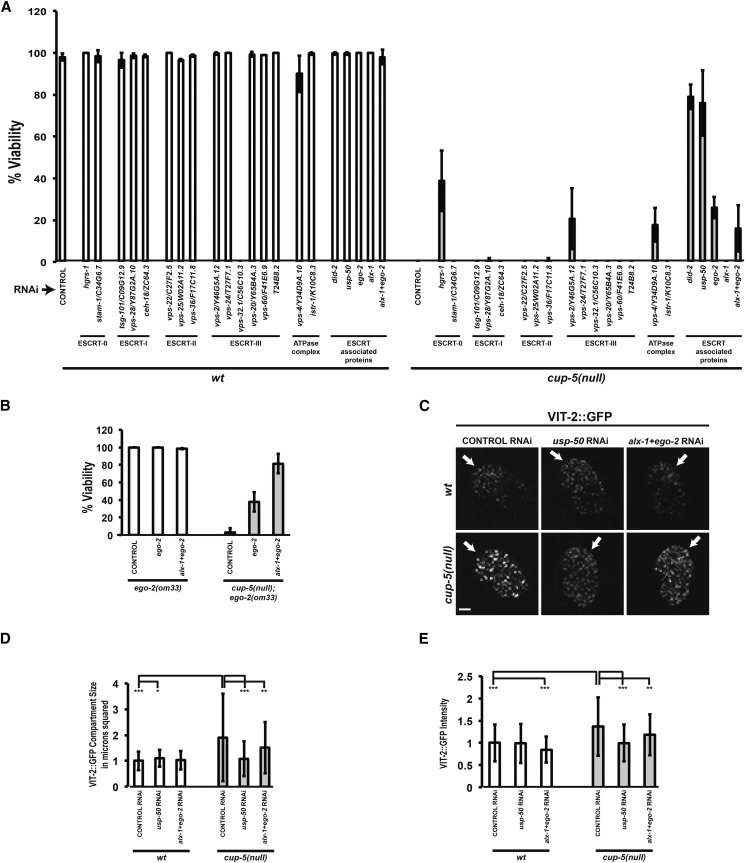

Reducing levels of other ESCRT-associated proteins also suppress embryonic lethality, lysosomal defect, and MRP-4 hypo-ubiquitination in cup-5(null)

We tested members of the ESCRT complex for RNAi suppression of cup-5(null) embryonic lethality. With the exception of vps-32.1/C56C10.3, RNAi of ESCRT genes did not cause significant lethality of wild-type embryos (Figure 6A). RNAi of hgrs-1, an ESCRT-0 protein, gave 38.8 ± 14.48% rescue of cup-5(null) embryonic lethality, although RNAi of the other ESCRT-0 gene, stam-1, gave no rescue (Figure 6A). In addition, RNAi of vps-2 (ESCRT-II) and vps-4 (ATPase complex) gave weak rescue of cup-5(null) lethality (Figure 6A).

Figure 6.

ESCRT RNAi suppression of cup-5(null) defects. (A) Percentage of viable worms laid by wild-type or cup-5(null) hermaphrodites after the indicated RNAi’s. (B) Percentage of viable worms laid by ego-2(om33) or cup-5(null); ego-2(om33) hermaphrodites after the indicated RNAi’s. (C) Confocal images of comma to 1.5-fold stage embryos laid by wild-type or cup-5(null) hermaphrodites carrying the VIT-2::GFP transgene after the indicated RNAi’s. All images were taken at the same exposure and magnification. Arrows indicate intestinal cells. Bar represents 10 µm. (D) Quantitation of surface area of VIT-2::GFP compartments in intestinal cells shown in C. (E) Quantitation of the intensity of the VIT-2::GFP compartments in intestinal cells shown in C. An asterisk indicates P < 0.05; two asterisks indicate P < 0.005; and three asterisks indicate P < 0.0005. Measurements were normalized to 1 in D and E using the wild-type control RNAi values.

We saw the strongest rescue of cup-5(null) lethality after RNAi of the ESCRT-associated genes usp-50, ego-2, and alx-1 (Figure 6A). USP-50 is the C. elegans homolog of S. cerevisiae Doa4p and human USP8/UBPY and EGO-2 and its homolog ALX-1 are the C. elegans homologs of human HD-PTP and Alix, respectively, and of S. cerevisiae Bro1p. While 0% of eggs laid by cup-5(null) hermaphrodites hatch, RNAi of usp-50 gave 76 ± 15.6% viability (Figure 6A). RNAi of ego-2 alone in cup-5(null) gave 26 ± 5.14% viability while RNAi of alx-1 gave no rescue of lethality (Figure 6A). RNAi of ego-2+alx-1 in cup-5(null) gave 16 ± 11.1% viability [which was not significantly different from the viability after RNAi of ego-2 alone in cup-5(null); P > 0.05] (Figure 6A). However, because combination RNAi’s are not as effective as single RNAi’s, and since EGO-2 and ALX-1 may have redundant ESCRT functions, we tested the ego-2+alx-1 RNAi in the presence of an ego-2(om33) hypomorphic allele that reduces EGO-2 activity. Indeed, RNAi of ego-2+alx-1 results in 81.17 ± 11.05% viability in the cup-5(null); ego-2(om33) background (Figure 6B).

Because of their strong suppression of cup-5(null) lethality, we focused our analysis on these ESCRT-associated proteins. We first assayed the degradation of VIT-2::GFP after reducing levels of these ESCRT-associated proteins in embryos laid by cup-5(null) hermaphrodites. Reducing levels of USP-50 suppresses both the cup-5(null) degradation defect and expanded lysosome size (Figure 6, C–E). Similarly, reducing levels of EGO-2+ALX-1 also suppresses the degradation defect and the expanded lysosome size in the cup-5(null) background (Figure 6, C–E). Similar to what we observed with DID-2 and MRP-4 proteins, these results indicate that the presence of USP-50 and ALX-1+EGO-2 is required for the appearance of the lysosomal defect in the absence of CUP-5.

The rescue of cup-5(null) lethality and the lysosomal defect by reducing levels of USP-50 and EGO-2+ALX-1 is not due to altering the endo-lysosomal localization of MRP-4 protein. Reducing levels of USP-50 in the cup-5(null) background resulted in an increase, rather than a decrease, in colocalization between MRP-4::GFP and LMP-1::RFP, while RNAi of alx-1+ego-2 resulted in no significant change in colocalization between the two proteins (Figure S4, A and B). This indicates that RNAi of these genes does not rescue cup-5(null) defects by trafficking MRP-4 protein away from the endo-lysosomal system where it does its damage.

We then assayed hypo-ubiquitination of MRP-4 protein in cup-5(null) to assess whether it was dependent on the presence of USP-50 or EGO-2+ALX-1. RNAi of usp-50 increases MRP-4 protein ubiquitination 7.7-fold at steady state in wild-type embryos when compared with control RNAi, consistent with its de-ubiquitinating activity (Figure 5C). This increase in MRP-4 ubiquitination is also seen after RNAi of usp-50 in cup-5(null) embryos at steady state with a 3.7-fold increase from control RNAi, establishing that cup-5(null) hypo-ubiquitination is dependent on USP-50 protein activity (Figure 5D). While RNAi of alx-1+ego-2 increases MRP-4 ubiquitination at steady state in wild-type embryos compared to control RNAi, we did not see an increase in MRP-4 ubiquitination in cup-5(null) embryos when compared to control RNAi (Figure 5, C and D). However, in the presence of the ego-2(om33) hypomorphic allele, reducing levels of alx-1+ego-2 increases MRP-4 protein ubiquitination at steady state in wild type (2.4-fold) and cup-5(null) (1.5-fold) embryos when compared with control RNAi (Figure 5, E and F).

ESCRT-associated/MRP-4 RNAi rescue of cup-5(null) lysosomal defects shows tissue and developmental specificity

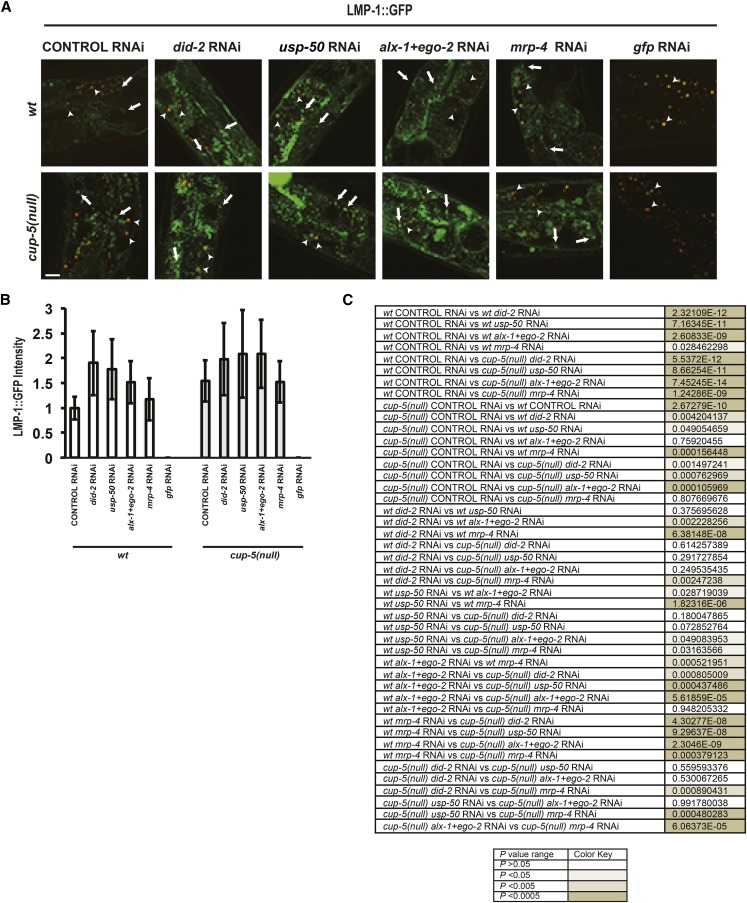

Is this genetic pathway linking ESCRT-associated proteins and MRP-4 with CUP-5 seen in developing intestinal cells in embryos also present in other tissues and at other stages of development? We first assayed GFP that is secreted by muscle cells and that is then endocytosed by coelomocytes; the GFP accumulates in terminal compartments (lysosomes) of the coelomocytes (Treusch et al. 2004). We measured GFP-filled compartment sizes because the intensity of endocytosed GFP in cup-5(null) coelomocytes was very bright compared to wild type and was saturated at the microscopy settings used to visualize wild-type coelomocytes. As we had previously shown, the GFP-filed compartments are larger in adult cup-5(null) compared to adult wild-type coelomocytes, indicating a lysosomal defect in the absence of CUP-5 (Figure S5, A–C) (Fares and Greenwald 2001b). RNAi of did-2, usp-50, alx-1+ego-2, or mrp-4 does not rescue this increased compartment size in adult cup-5(null) coelomocytes (Figure S5, A–C). Indeed, while RNAi of the ESCRT-associated proteins did not significantly alter the GFP-filled compartment sizes of adult wild-type coelomocytes, RNAi of did-2 and alx-1+ego-2 significantly increased GFP-filled compartment sizes of adult cup-5(null) coelomocytes (Figure S5, A–C). Thus, the suppression of cup-5(null) lysosomal defects by RNAi of ESCRT-associated proteins or MRP-4 in developing intestinal cells in embryos does not occur in adult coelomocytes.

We then assayed the adult intestine to determine whether RNAi of ESCRT-associated proteins or MRP-4 rescues lysosomal defects in intestinal cells of adult cup-5(null) worms. The levels of the lysosomal marker, LMP-1::GFP, are increased in the adult intestine of cup-5(null) hermaphrodites compared to wild type, indicating a lysosomal defect in the absence of CUP-5 (Figure 7, A–C). RNAi of did-2, usp-50, alx-1+ego-2, and mrp-4 cause an increase in LMP-1::GFP levels in wild-type adult intestines, consistent with their functioning in this tissue. However, RNAi of these ESCRT-associated proteins or MRP-4 did not rescue the increased LMP-1::GFP levels in cup-5(null) adults (Figure 7, A–C). Thus, this genetic pathway that is evident in embryonic intestinal cells is absent in adult intestinal cells.

Figure 7.

ESCRT RNAi suppression in adult intestine. (A) Confocal images of adult wild type (wt) and cup-5(null) (zu223 allele) intestine expressing LMP-1::GFP after the indicated RNAi’s. All images were taken using the same exposure and magnification. Arrows indicate LMP-1::GFP compartments. Arrowheads indicate autofluorescent gut granules. Bar, 10 µm. (B) Quantitation of the intensity of LMP-1::GFP in compartments shown in A. Measurements were normalized to 1 using the wild-type control RNAi value. (C) Table of P values for all pairwise tests in B.

Taken together, the data suggest that cup-5(null) suppression by RNAi of the ESCRT-associated proteins and MRP-4 exhibits tissue and developmental specificity.

Discussion

In this study, we uncover a novel genetic link between CUP-5 and ESCRT-associated proteins. Our model is that the absence of CUP-5 results in increased activity of the de-ubiquitinating enzyme USP-50, as evidenced by the suppression of cup-5(null) defects after reducing the levels of the ESCRT-associated proteins DID-2, USP-50, or ALX-1+EGO-2. Our results also suggest that this ESCRT-associated defect impacts lysosomal functions and embryonic lethality in the absence of CUP-5 at least in part through affecting the activity of the ABC transporter MRP-4 and possibly by altering the levels and/or activities of other proteins.

We found that the loss of CUP-5 resulted in increases in levels of DID-2 and MRP-4 proteins. The increase in DID-2 levels is not due to altered degradation or TFEB-mediated transcriptional activation in the absence of CUP-5. In contrast, our studies suggest that the increase in MRP-4 levels is due to altered transcription that is mediated by HLH-30/TFEB. However, other studies have shown that, under lysosomal stress conditions, Ca2+ released from lysosomes by TRPML1 causes the translocation of TFEB to the nucleus where it activates transcription (Medina et al. 2015). Therefore, how does HLH-30 translocate to the nucleus to increase transcription of mrp-4 when CUP-5 is not present to release Ca2+ from lysosomes? Our model is that the lysosomal defect in the absence of CUP-5 leads to lysosome rupture or leakiness, thus releasing Ca2+ into the cytoplasm. Indeed, the lysosomal protease Cathepsin B has been found to leak into the cytoplasm after severe knockdown of TRPML1 in HeLA cells (Colletti et al. 2012).

Although we detect changes in the levels of DID-2 and MRP-4 in the absence of CUP-5, our results show that the increased levels of these proteins do not contribute to cup-5(null) lethality. Therefore, while these gene expression changes are phenotypes of cup-5(null) tissues, they do not impact lysosomal functions or tissue viability. Which phenotypes, then, are relevant?

We propose that the hypo-ubiquitination of MRP-4 protein in cup-5(null) is a major contributor to the lysosomal and viability defects since both defects are rescued by reducing the levels of ESCRT-associated proteins, including the catalytic enzyme USP-50. Surprisingly, given the established functions of ESCRT proteins in shuttling receptors for degradation, this hypo-ubiquitination of MRP-4 in the absence of CUP-5 had no effect on the levels of MRP-4 protein. Our model is that the mono-ubiquitin state of MRP-4 protein modulates its activity, where hypo-ubiquitination of MRP-4 results in increased MRP-4 transporter activity leading to lysosomal defects and ultimately to tissue death. In addition, since overexpression of MRP-4 is not sufficient to cause embryonic lethality, this suggests that the mono-ubiquitination of MRP-4 is used to regulate the total transporter activity of MRP-4 in late endosomes/lysosomes, irrespective of how much MRP-4 protein is present in these compartments. Our results show that CUP-5 directly or indirectly regulates the activity of the ESCRT-associated proteins such that loss of CUP-5 results in their mis-regulation. The question then becomes, is there a biochemical link between CUP-5 and the ESCRT-associated proteins?

Studies in other systems have uncovered a potential link between TRPML1 and ESCRT-associated proteins. Human TRPML1 binds the penta-EF-hand protein ALG2 (Vergarajauregui et al. 2009). In other studies, ALG2 was found to interact with Alix and HD-PTP, the human homologs of ALX-1 and EGO-2 (Missotten et al. 1999; Vito et al. 1999; Ichioka et al. 2007). Our future studies will probe the functionality of this potential link between the Ca2+ channel CUP-5, the Ca2+-binding protein M04F3.4 (worm homolog of ALG2), and ALX-1/EGO-2, the yeast homolog Bro1p of which binds and activates the de-ubiquitinase Doa4p and where human HD-PTP (worm EGO-2) was found to bind UBPY (worm USP-50) as a part of EGFR’s ESCRT pathway (Richter et al. 2007; Ali et al. 2013). These studies would delineate how CUP-5 regulates ESCRT-associated proteins and how these ESCRT-associated proteins are misregulated in the absence of CUP-5.

We have uncovered a novel link between CUP-5 and ESCRT-associated proteins that suggests coordinate regulation of lysosome formation and function via CUP-5 with the de-ubiquitination and intraluminal sequestration of cargo in late endosomes via ESCRT-associated proteins. This genetic link seems to be present only in certain tissues and developmental stages. Thus, CUP-5 may have functions that are unique to some tissues, which may be one of the reasons why MLIV patients and mouse models of the disease show developmental and neurological defects that are more severe than in other tissues (Altarescu et al. 2002; Grishchuk et al. 2015).

Acknowledgments

We thank Eleanor Maine (Syracuse University) for the ego-2 cDNA construct; Patty Jansma for microscopy assistance; Bhavani Bagevalu Siddegowda for qRT-PCR assistance; and Teresa Horm for helpful discussions. This work was supported by a Microscopy Society of America grant (to J.H.) and by National Science Foundation grant 3004290 (to H.F.).

Footnotes

Communicating editor: B. Goldstein

Supporting information is available online at www.genetics.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1534/genetics.115.182485/-/DC1.

Literature Cited

- Ali N., Zhang L., Taylor S., Mironov A., Urbe S., et al. , 2013. Recruitment of UBPY and ESCRT exchange drive HD-PTP-dependent sorting of EGFR to the MVB. Curr. Biol. 23: 453–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altarescu G., Sun M., Moore D. F., Smith J. A., Wiggs E. A., et al. , 2002. The neurogenetics of mucolipidosis type IV. Neurology 59: 306–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach G., 2001. Mucolipidosis type IV. Mol. Genet. Metab. 73: 197–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bargal R., Avidan N., Ben-Asher E., Olender Z., Zeigler M., et al. , 2000. Identification of the gene causing mucolipidosis type IV. Nat. Genet. 26: 118–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassi M. T., Manzoni M., Monti E., Pizzo M. T., Ballabio A., et al. , 2000. Cloning of the gene encoding a novel integral membrane protein, mucolipidin, and identification of the two major founder mutations causing mucolipidosis type IV. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 67: 1110–1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer B. E., Wolfger H., Kuchler K., 1999. Inventory and function of yeast ABC proteins: about sex, stress, pleiotropic drug and heavy metal resistance. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1461: 217–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers K., Lottridge J., Helliwell S. B., Goldthwaite L. M., Luzio J. P., et al. , 2004. Protein-protein interactions of ESCRT complexes in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Traffic 5: 194–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozzato A., Barlati S., Borsani G., 2008. Gene expression profiling of mucolipidosis type IV fibroblasts reveals deregulation of genes with relevant functions in lysosome physiology. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1782: 250–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner S., 1974. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77: 71–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell E. M., Fares H., 2010. Roles of CUP-5, the Caenorhabditis elegans orthologue of human TRPML1, in lysosome and gut granule biogenesis. BMC Cell Biol. 11: 40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colletti G. A., Miedel M. T., Quinn J., Andharia N., Weisz O. A., et al. , 2012. Loss of lysosomal ion channel transient receptor potential channel mucolipin-1 (TRPML1) leads to cathepsin B-dependent apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 287: 8082–8091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean M., Hamon Y., Chimini G., 2001. The human ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter superfamily. J. Lipid Res. 42: 1007–1017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X. P., Cheng X., Mills E., Delling M., Wang F., et al. , 2008. The type IV mucolipidosis-associated protein TRPML1 is an endolysosomal iron release channel. Nature 455: 992–996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fares H., Greenwald I., 2001a Genetic analysis of endocytosis in Caenorhabditis elegans: coelomocyte uptake defective mutants. Genetics 159: 133–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fares H., Greenwald I., 2001b Regulation of endocytosis by CUP-5, the Caenorhabditis elegans mucolipin-1 homolog. Nat. Genet. 28: 64–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukushige T., Hawkins M. G., McGhee J. D., 1998. The GATA-factor elt-2 is essential for formation of the Caenorhabditis elegans intestine. Dev. Biol. 198: 286–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goujon M., McWilliam H., Li W. Z., Valentin F., Squizzato S., et al. , 2010. A new bioinformatics analysis tools framework at EMBL-EBI. Nucleic Acids Res. 38: W695–W699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham P. L., Kimble J., 1993. The mog-1 gene is required for the switch from spermatogenesis to oogenesis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 133: 919–931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant B., Hirsh D., 1999. Receptor-mediated endocytosis in the Caenorhabditis elegans oocyte. Mol. Biol. Cell 10: 4311–4326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grishchuk Y., Pena K. A., Coblentz J., King V. E., Humphrey D. M., et al. , 2015. Impaired myelination and reduced brain ferric iron in the mouse model of mucolipidosis IV. Dis. Model. Mech. 8: 1591–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadwiger G., Dour S., Arur S., Fox P., Nonet M. L., 2010. A monoclonal antibody toolkit for C. elegans. PLoS One 5: e10161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henne W. M., Buchkovich N. J., Emr S. D., 2011. The ESCRT pathway. Dev. Cell 21: 77–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hersh B. M., Hartwieg E., Horvitz H. R., 2002. The Caenorhabditis elegans mucolipin-like gene cup-5 is essential for viability and regulates lysosomes in multiple cell types. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99: 4355–4360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichioka F., Takaya E., Suzuki H., Kajigaya S., Buchman V. L., et al. , 2007. HD-PTP and Alix share some membrane-traffic related proteins that interact with their Bro1 domains or proline-rich regions. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 457: 142–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamath R. S., Ahringer J., 2003. Genome-wide RNAi screening in Caenorhabditis elegans. Methods 30: 313–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzmann D. J., Babst M., Emr S. D., 2001. Ubiquitin-dependent sorting into the multivesicular body pathway requires the function of a conserved endosomal protein sorting complex, ESCRT-I. Cell 106: 145–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostich M., Fire A., Fambrough D. M., 2000. Identification and molecular-genetic characterization of a LAMP/CD68-like protein from Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Cell Sci. 113(Pt 14): 2595–2606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapierre L. R., De Magalhaes Filho C. D., McQuary P. R., Chu C. C., Visvikis O., et al. , 2013. The TFEB orthologue HLH-30 regulates autophagy and modulates longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat. Commun. 4: 2267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]