Abstract

Increasing antibiotic resistance among uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC) is driving interest in therapeutic targeting of nonconserved virulence factor (VF) genes. The ability to formulate efficacious combinations of antivirulence agents requires an improved understanding of how UPEC deploy these genes. To identify clinically relevant VF combinations, we applied contemporary network analysis and biclustering algorithms to VF profiles from a large, previously characterized inpatient clinical cohort. These mathematical approaches identified four stereotypical VF combinations with distinctive relationships to antibiotic resistance and patient sex that are independent of traditional phylogenetic grouping. Targeting resistance- or sex-associated VFs based upon these contemporary mathematical approaches may facilitate individualized anti-infective therapies and identify synergistic VF combinations in bacterial pathogens.

Keywords: uropathogens, UPEC, UTI, antibiotic resistance, novel therapeutic targets, sex specificity in infections, network analysis

Antibiotic resistance is widely recognized as one of the 21st century’s pre-eminent public health challenges. There is also a growing appreciation that conventional broad-spectrum antibiotic strategies exert deleterious “off-target effects” on the human microbiome.1,2 Antibiotic therapies for urinary tract infections (UTIs), which are predominantly caused by uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC), have come to exemplify both challenges. UPEC are becoming notably resistant to the potent oral trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and fluoroquinolones that have long been a mainstay of outpatient UTI therapy,3,4 presenting an increasing healthcare burden.5 Fluoroquinolone use has also been implicated in the rise of community-acquired Clostridium difficile, an opportunistic infection that takes root when the intestinal microbiome is disturbed by antibiotic exposure.6 These shortcomings of current broad-spectrum antibiotic approaches have motivated renewed interest in precision therapeutic approaches directed against pathogen-specific molecular targets that circumvent existing resistance mechanisms and spare beneficial members of the gut microbiome. Chief among these are antivirulence agents that selectively disarm pathogenic functions in bacteria without suppressing beneficial functions of intestinal microbes.7

Prior studies, aided by UPEC’s genetic tractability, have identified numerous monogenic urovirulence determinants in clinical E. coli isolates. Many of these genetic loci, termed virulence factors (VFs), are nonconserved or are carried on mobile genetic elements and are known to execute specific biochemical functions related to uropathogenesis.8 The biochemical functions of many VFs are known in sufficient detail to permit prototype antivirulence therapeutic agents to be identified or developed. VFs associated with iron acquisition systems (siderophores9), in particular, have been targeted by biosynthetic inhibitors,10 import inhibitors, and “Trojan horse” toxins such as pesticin, albomycin, and microcins.11−14E. coli adhesins have also been targeted for inhibition in approaches that could be expanded to other adhesin types.15−17 Continued efforts are likely to provide an expanded panel of antivirulence agents that may be combined to maximize clinical efficacy.

An important theoretical weakness of antivirulence therapies arises from the targets’ potentially brief period of pathophysiologically relevant activity, which may limit an agent’s efficacy. Just as uropathogenic adaptations are generally multifactorial in nature, antivirulence agents will likely have to be combined for efficacy.18,19 In addition to increasing efficacy, combination drug approaches typically limit the rate at which resistant mutants emerge by forcing pathogens to develop multiple simultaneous resistance adaptations. These principles underlie current combination anti-infective therapies against Helicobacter pylori, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and HIV. Although combined siderophore and adhesin inhibitor therapy may be similarly effective against uropathogenic E. coli, it has been unclear how to optimally combine these agents to best treat urological infections. Currently unexplored associations between UPEC VFs further complicate combination antivirulence therapeutic formulations for UTI.

To determine which antivirulence target combinations predominate in patients, we applied mathematical network community detection and statistical biclustering to uropathogenic E. coli VF genotypes from a previously described hospitalized UTI patient cohort with a high incidence of antibiotic resistance, pyelonephritis, and bacteremia.20 The mathematical tools used here21−23 simultaneously considered VF genotypes and their frequency among 337 clinical pathogenic isolates and identified 4 stereotypical urovirulence strategists. These strategists were independently associated with antibiotic resistance and patient sex. These results provide a preliminary framework for devising and prioritizing combinatorial antivirulence strategies and support the use of these mathematical approaches to address this and other unresolved questions in infectious diseases.

Results and Discussion

Clinical Isolate Characteristics

Three hundred and thirty-seven bacteriuric inpatient E. coli clinical isolates (CIs) were derived from a recently described inpatient cohort collected over the course of one year (Table 1).20 The CIs characterized in this study were predominantly female (n = 263, 78%), with a median inpatient age range of 62 years (range, 19–101 years). One hundred and seven patients had pyelonephritis (32%), 60 had sepsis-induced hypotension (17%), and 24 had bacteremia (7%). The E. coli phylogenetic group distribution was typical of urinary isolates, with a majority of strains contained in group B2 (68%).24 One hundred and seventeen isolates were resistant to ciprofloxacin (CIP, 35%), and 96 were resistant to trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMP/S, 29%).

Table 1. Clinical Characteristics of Clinical Isolates Tested in This Study.

| metric | total (%) |

|---|---|

| female | 263 (78) |

| male | 74 (22) |

| pyelonephritis | 107 (32) |

| sepsis-induced hypotension (SIH) | 60 (17) |

| bloodstream infection (BSI) | 24 (7) |

| ciprofloxacin (CIP) resistant | 117 (35) |

| trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMP/S) resistant | 96 (29) |

| phylogenetic group B2 | 232 (68) |

| phylogenetic group D | 54 (16) |

| phylogenetic group B1 | 41 (12) |

| phylogenetic group A | 10 (3) |

Virulence Factor Distribution

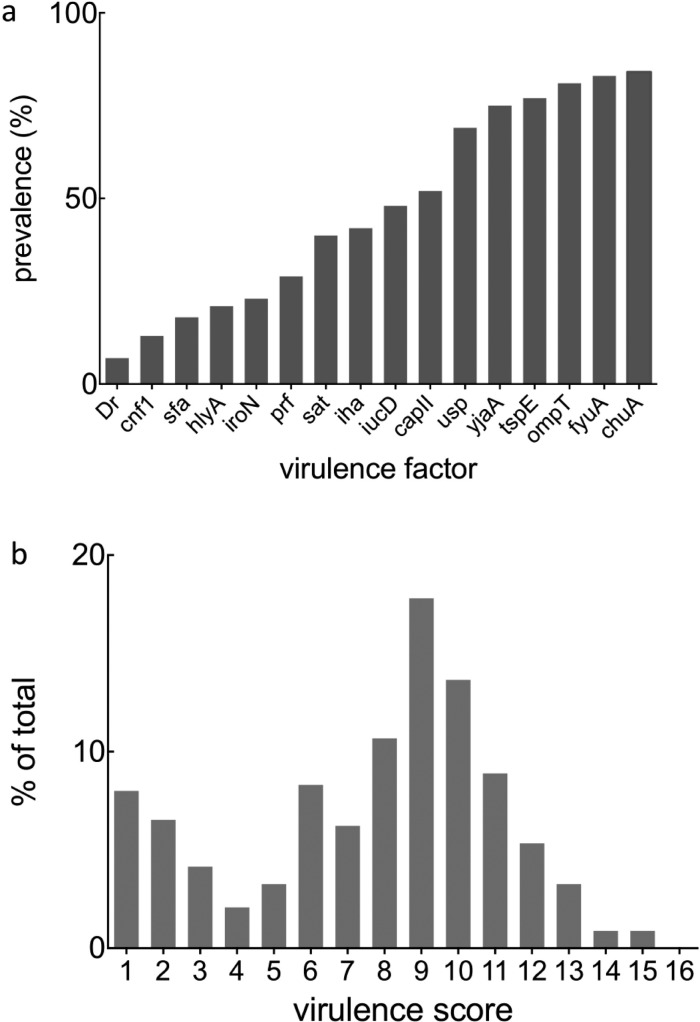

CIs were assessed for the presence or absence of 16 VF genes (Table 2) that have been collectively addressed in over 2700 publications (Figure S1). One hundred and twenty-seven unique, nonredundant VF genotypes were present among the clinical isolates examined in this study. Virulence factor prevalence ranged from highly common (chuA; 84%) to infrequent (Dr; 7%, Figure 1a). Using a z test for normality, we found that the gene content is not normally distributed (p = 0.031). Indeed, a histogram of VF gene content frequency reveals a bimodal distribution with local maxima at one and nine virulence factors (Figure 1b). This bimodal distribution is consistent either with two quantitative optima for VF content or with the tendency of VFs to occur in modular combinations. An overview by principal component analysis (PCA) did not clearly resolve any coherent patterns in this data set (Figure S2).

Table 2. Virulence Factors and Their Functions.

| gene | function |

|---|---|

| chuA | E. coli heme uptake |

| fyuA | siderophore (yersiniabactin uptake) |

| ompT | surface protease |

| tspE | anonymous DNA fragment |

| yjaA | hypothetical protein |

| usp | bacteriocin |

| capII | group II capsule antigen |

| iucD | siderophore (aerobactin) |

| iha | irgA homologue adhesin |

| sat | secreted autotransporter toxin |

| prf | adhesion (P-related fimbriae) |

| iroN | siderophore (salmochelin) |

| hlyA | hemolysin |

| sfa | adhesion (S-fimbriae) |

| cnf1 | cytotoxic necrotizing factor |

| Dr | adhesion (Dr family) |

Figure 1.

Virulence factor incidence and distribution among the clinical isolates examined in this study: (a) Virulence factor incidence in the 337 clinical isolatesi shown. (b) Each virulence factor (VF) was assigned a score of 1. Any virulence score ≥1 indicates the presence of one or more VFs, and 0 is the absence of individual genes. Because the presence and absence of all 16 genes were considered, the VF score ranged from 0 to 16. Next, a data matrix was generated to determine each clinical isolate’s VF profile. A bimodal distribution of virulence scores was observed among 337 clinical isolates, with local maxima at one and nine virulence factors.

Network Community Detection of Uropathogenic Strategies

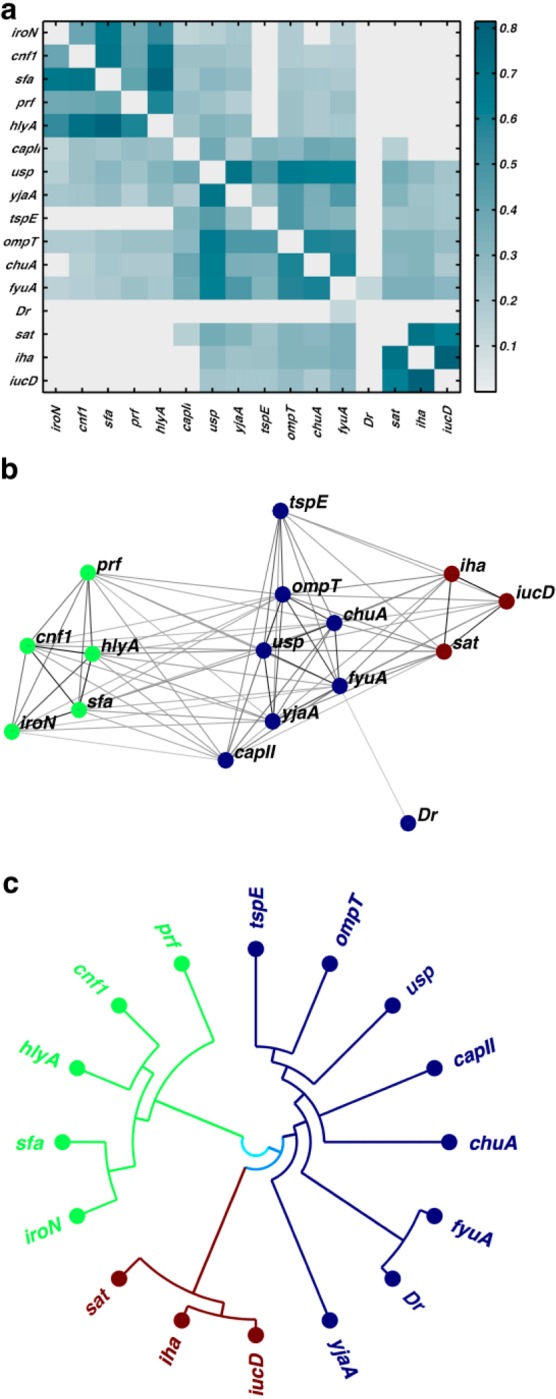

To determine whether UPEC VFs are associated with each other in stereotypical patterns, we next applied modularity-based community detection to a network of the 16 VFs alone. We set weighted edges between VFs by statistically significant positive correlations (by Fisher’s exact test at the 1.5% one-sided level to ensure a single component connecting all 16 VFs). Three interrelated VF communities are discernible within the resulting heatmap (Figure 2a), corresponding force-directed layout (Figure 2b), and VF nested hierarchy of communities (Figure 2c). Siderophore genes are uniquely represented in each VF community (VF community 1, fyuA; VF community 2, iroN; VF community 3, iucD). Weaker positive correlations between the fyuA-containing VF community and those containing iucD or iroN are evident in the VF adjacency matrix. Network community detection thus shows that the clinical E. coli isolates deploy VFs in stereotypical combinations.

Figure 2.

Network community detection clusters 16 virulence factors into three discrete communities. (a) Three VF communities are evident in an empirical heatmap depicting statistically significant positive correlations between VFs. (b) A force-directed layout illustrates connectivities between individual virulence factors (VFs) organized into three VF communities (colors). (c) Nested hierarchy of communities of VF genes in a polar coordinate dendrogram are colored according to community identification at default resolution (three communities). Each VF community contains a distinct siderophore gene (iroN, fyuA, iucD).

Network Community Detection of Clinical Isolates

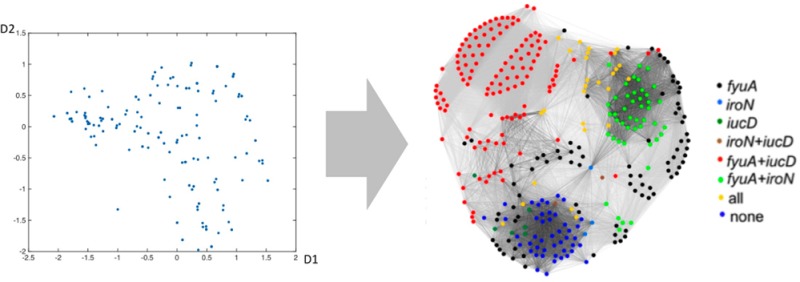

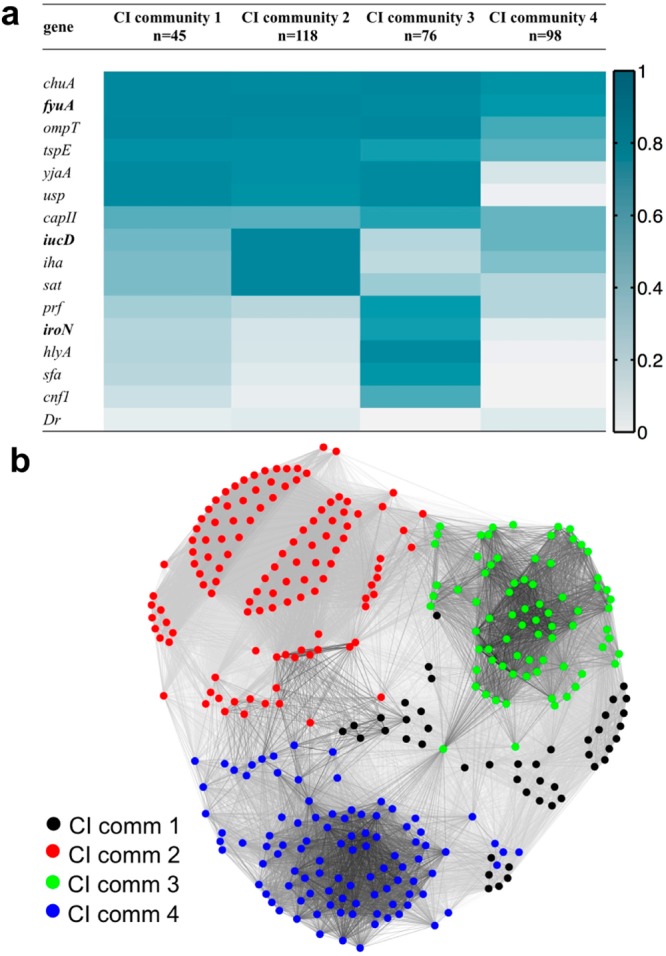

To determine whether UPEC carry stereotypical VF combinations, we applied modularity-based community detection to a network representation of the 337 clinical isolates. We defined a CI network of positively associated pairs after correcting for each VF’s mean frequency and variance across the study population (see Methods for details). Modularity-based community detection resolves four clinical isolate communities (CI communities 1–4, n = 45, 118, 76, and 98, respectively), representing four distinct virulence strategists (Figure 3a). Each community contains distinctive VF patterns that together encompass multiple functional classes. A force-directed layout of this network indicates connectivity and strength of association between UPEC isolates (Figure 3b). These stereotypical distributions suggest that virulence genes are present as modular communities from which relevant antivirulence targets can be prioritized.

Figure 3.

Network community detection clusters 337 inpatient clinical isolates into four discrete communities. (a) Four distinct communities (identified using modularity maximization) describe the CIs in this population. Color scale: dark blue, VF presence = 100%; white, ≤5%. (b) A force-directed layout illustrates associations between virulence factor (VF) profiles of individual UPEC clinical isolates (CIs). Each node represents a CI, and connecting line (edge) lengths are determined to most closely match the connectivity level between the connected CIs (colored by CI community assignment).

Biclustering Analysis

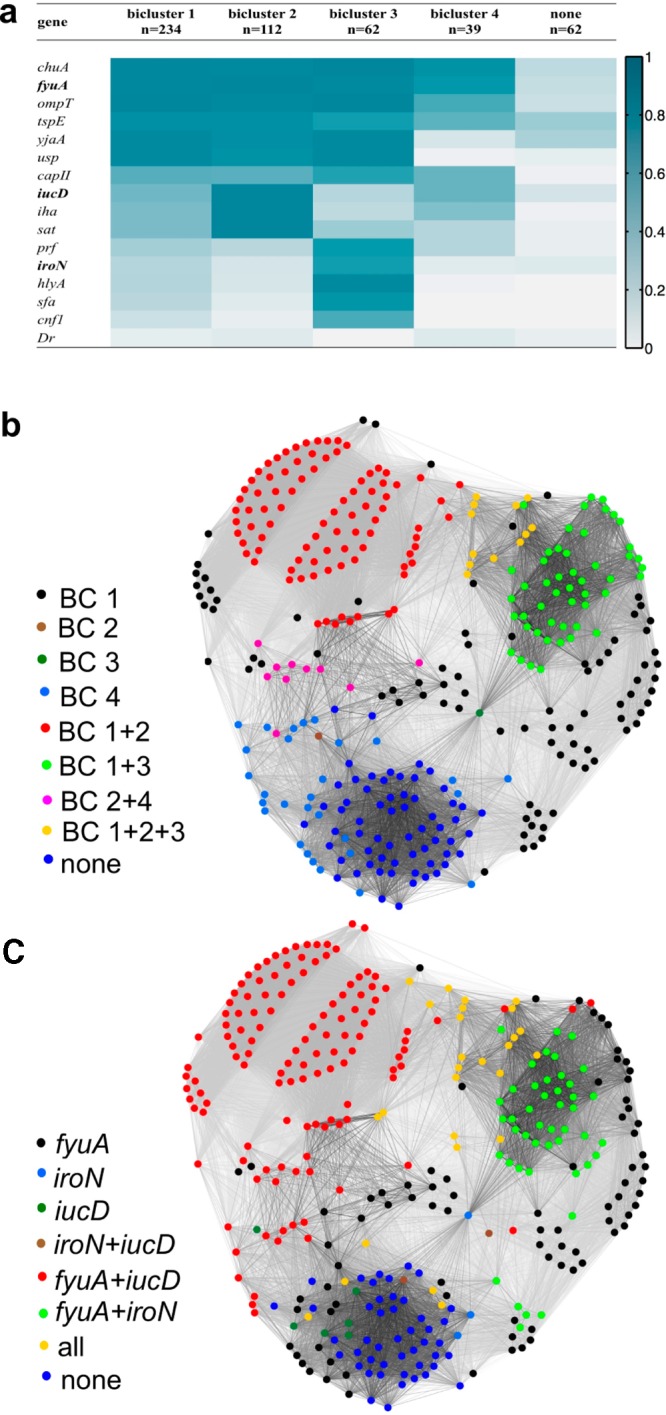

As a complementary alternative to network community detection, we employed an iterative binary biclustering method based on the large average submatrix (LAS) procedure described by Shabalin et al.23 Whereas network-based community detection assigns each VF or clinical isolate to a single community, biclustering simultaneously identifies highly co-occurring VFs and CIs. A CI or VF may belong to multiple biclusters (BCs) or none at all. Four BCs emerge from our clinical population (BC 1–4, n = 234, 112, 62, and 39, respectively; Figure 4a), in a manner consistent with the four virulence strategists identified by network community detection. Overall, VFs associated with each bicluster are highly expressed across the constituent CIs (>72%). Biclustering did not classify 62 CIs with low VF gene content, the collection of which grossly resembles CI community 4. BC 4 is mostly redundant with BC 1 but is most distinguished by the absence of two genes (sfa and cnf1) and the low prevalence of four genes (yjaA, usp, iroN, and hlyA). The most abundant classifications resemble the CI communities, with the largest single bicluster combination (BC1+2, strains appearing in BC1 and BC2 but no other BCs, n = 89) closely resembling CI community 2. By annotating the force-directed layout of the CI strains with bicluster assignments, we reveal many similarities between the two clustering results (Figures 3b and 4b). The stereotypical VF combinations identified by both mathematical approaches define four stereotypical virulence strategists among UPEC in the study population.

Figure 4.

Bicluster and siderophore gene composition cluster clinical isolates similarly to network analysis. (a) Four biclusters describe 82% of the CIs in this population. Siderophore genes are in bold type. Color scale: dark blue, VF presence = 100%; white, ≤5%. (b, c) The force-directed layout for clinical isolates overlaid with each CI’s bicluster assignments (b) and siderophore genotype (c) illustrates overall similarities between these CI classification approaches and the communities in Figure 1b.

Virulence Strategists and Phylogeny

E. coli phylogenetic groups have been used extensively to classify clinical E. coli isolates and consistently associate group B2 with extraintestinal infections. We investigated whether CI phylogenetic groups are more informative than the stereotypical VF communities by seeking associations with CI communities and biclusters (Table S1). Assignment to non-B2 phylotypes is associated with C4, BC4, or nonbiclustered strains. Phylogenetic type otherwise exhibited no other clear associations with other VF-defined groupings. These results reveal that the best-resolved virulence strategies represent an organizational level that is distinct from phylogenetic grouping.

Virulence Strategists and Siderophores

Network community detection and biclustering each identify collections that possess stereotypical combinations of siderophores, toxins, and adhesins. Among single functional classes, siderophore genotypes effectively distinguish these communities and biclusters from one another. E. coli siderophores exhibit diverse structures that likely represent evolutionary adaptive radiation such that one siderophore system may represent a gain of function, whereas another may represent functional redundancy.25−28 Siderophore systems have also been subject to extensive targeted drug development studies in bacteria.13,29 We therefore examined siderophore genotypes as an independent way to characterize UPEC strategists. Overlaying siderophore genotypes on the force-directed layout (Figure 4c) reveals this nonrandom siderophore gene distribution. We observed that a representative siderophore genotype characterizes each CI community (CI community 1 is 88.9% fyuA only; CI community 2 is 93.2% fyuA+iucD; community 3 is 51.3% fyuA+iroN; CI community 4 is 46.9% none). Similarly, representative siderophore genes characterize each BC (BCs 1 and 4 are 61.9% and 34.5% fyuA only, respectively; BC 1+2 is 94.4% fyuA+iucD; BC 3 is 100% iroN). Siderophore genotypes are thus strongly associated with the virulence strategists identified by network community detection and bicluster analysis.

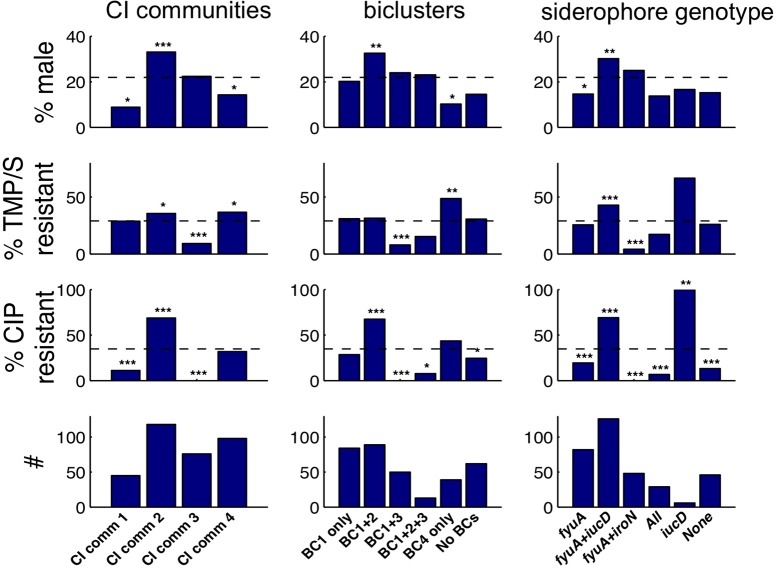

Virulence Strategists and Patient Sex

To assess the four virulence strategists’ clinical significance, we first investigated associations with patient sex, an organizing principle in UTI medical management. The abundant fyuA+iucD strategists (CI community 2, BCs 1+2) are highly associated with male sex (33.1, 32.6, and 30.2%, respectively, compared to the 22% male study population; each deviation is statistically significant as indicated in Figure 5). Female sex, classically a UTI-susceptible population, is predominantly associated with fyuA strategists (CI community 1 and BC 4; 8.9 and 10.3% male, respectively). Sex preferences among different virulence strategists may reflect their preferential adaptation to sex-dependent host niches such as the vaginal mucosa, the prostate and its secretions, urethral length, sex differences in immune defenses, hormonal differences, or a combination thereof. These findings suggest that some antivirulence strategies may be particularly useful in a precision medicine context where individual patient factors such as sex guide therapeutic selection.

Figure 5.

CI classifications correspond to antibiotic resistance and patient sex. Patient sex and antibiotic resistance (bars) in each clinical isolate subgroup relative to total study population (dashed lines) are shown. Subgroup size (#) is indicated in the bottom row. Small subgroups (<6 CI) were omitted for clarity. fyuA+iucD strategists (community 2, BC1+2) exhibit notable sex and ciprofloxacin resistance associations. Statistical significance determined by Fisher’s exact test is indicated by number of asterisks (p values: 0.05, 0.01, and 0.001, respectively, without correction for multiple testing).

Virulence Strategists and Antibiotic Resistance

To determine whether the four virulence strategists are linked with antibiotic resistance, we investigated associations with phenotypic resistance to the two frequently used oral antibiotics trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP/S) and ciprofloxacin (CIP) (Figure 5). The abundant fyuA+iucD strategists (CI community 2 and BC 1+2; 68.6 and 73.2% total siderophore genotypes, respectively) are highly associated with CIP resistance and moderately associated with TMP/S resistance (Figure 5). Conversely, the fyuA+iroN siderophore genotype (CI community 3, BC 1+3) is highly susceptible to both CIP and TMP/S. These results indicate that virulence strategies are linked to antibiotic responses. Combinatorial targeting of the fyuA+iucD siderophore genotype may thus represent an alternative antivirulence strategy against UPEC strains that are resistant to standard antibiotic therapies.

Multivariate Analysis

Because virulence strategists were associated with both patient sex and antibiotic resistance (Figure 5), we used nested multivariate logistic regression analyses to determine whether virulence strategies and patient sex contribute independently to antibiotic resistance (Table 3). Incremental addition of VF content to patient sex in the nested model reveals that VF groupings (CI communities, biclusters, or siderophore genotype) are associated independently with antibiotic resistance. To determine which virulence strategists are associated with resistance, we conducted logistic regression analyses with models including each of the three nested strategies. In these analyses, male sex and fyuA+iucD siderophore genotype (CI community 2, BC 1+2) are independently associated with CIP resistance, whereas TMP/S resistance is associated with the fyuA+iucD siderophore genotype (but not CI community 2 or BC 1+2). Conversely, the fyuA+iroN siderophore genotype (CI community 3, BC 1+3) and BC 1, BC 1+2, and BC 1+2+3 are each strongly associated with TMP/S susceptibility, whereas patient sex is not. Virulence strategies are associated with antibiotic resistance independently of the sex of the patients from whom they were recovered. Targeting specific virulence strategists in this population therefore suggests new treatment strategies for antibiotic-resistant uropathogens.

Table 3. Patient Sex and E. coli Virulence Groupings Are Strongly Associated with Ciprofloxacin (CIP) and Trimethoprim/Sulfa (TMP/S) Resistancea.

| nested multivariate analysis |

logistic regression analysis |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| antibiotic | model | deviance | covariate | OR |

| CIP | sex | 415*** | male | 3.5 (2.0–6.0)*** |

| sex + CI communities | 287*** | C2 | 15.0 (6.0–47.0)*** | |

| male | 3.9 (1.9–8.2)*** | |||

| C4 | 4.0 (1.4–11.0)* | |||

| sex + biclusters | 322*** | male | 4.7 (2.4–9.6)*** | |

| BC 1+2 | 2.1 (1.0–4.7)* | |||

| BC 1 | 0.4 (0.2–0.9)* | |||

| sex + siderophore genotype | 294*** | fyuA+iucD | 8.0 (5.0–15.0)*** | |

| male | 4.1 (2.1–8.6)*** | |||

| TMP/S | sex | 405 | ||

| sex + CI communities | 382*** | C3 | 0.2 (0.1–0.4)*** | |

| sex + biclusters | 380*** | BC 1+3 | 0.1 (0.0–0.3)*** | |

| BC 1+2+3 | 0.1 (0.0–0.5)* | |||

| BC 1 | 0.5 (0.2–0.9)* | |||

| BC 1+2 | 0.4 (0.2–0.9)* | |||

| sex + siderophore genotype | 373*** | fyuA+iucD | 2.0 (1.4–3.7)** | |

| fyuA+iroN | 0.1 (0.0–0.5)** | |||

In the nested multivariate analyses, lower deviance indicates improved fit to the model. In the logistic regression analyses, odds ratios (OR) of resistance per covariate are shown (with 95% confidence intervals). Only the statistically significant variables from each model are listed for clarity. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.00001.

The contemporary mathematical exploratory tools used here show that E. coli VFs tend to exist in stereotypical combinations, which define unique bacterial “strategists”, in bacteriuric specimens from a well-characterized patient cohort. Intriguingly, discrete uropathogenic strategists are associated with the clinically important variables of antibiotic resistance and patient sex. These clinical associations suggest that specific VF combinations are worthy of further consideration as combinatorial antivirulence therapeutic targets. Furthermore, the tendency for antibiotic-resistant E. coli to carry VF communities associated with yersiniabactin (fyuA) and aerobactin (iucD) genes suggests new therapeutic targets for uropathogenic isolates in which existing antibiotics are failing.

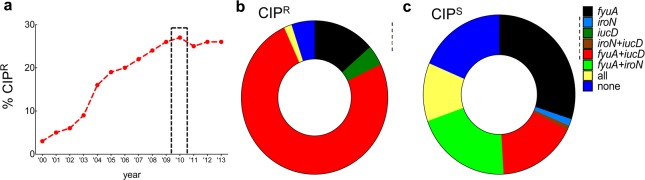

The striking increase in ciprofloxacin-resistant (CIPR) isolates at the study institution over the past 15 years (Figure 6a) parallels the worldwide trend30 and prompts a closer look at the virulence strategy–CIPR association. Mining the extensive literature on worldwide fluoroquinolone resistance in UPEC suggests that the virulence strategists identified in this study may correspond to other geographic locations. In the present study, 75% of CIPR isolates possess fyuA+iucD, whereas none have the fyuA+iroN siderophore genotype (Figure 6b,c). Similar monogenic E. coli siderophore correlates of CIPR were observed in studies examining nonclonal strains from China, Italy, Iran, Israel, Korea, and Australia.31−36 Furthermore, when genetically distinct CIPRE. coli strains (ST131, ST1193, and O15:K52:H1) from geographically distinct locations were characterized by full genome sequencing, aerobactin genes (iucD, iutA) were present and salmochelin genes (iroBCDEN) were absent.37−39 Interestingly, CIPS correlates were correlated with iroN expression in studies conducted in India and France.40,41 Whereas a more systematic international comparison would be more definitive, these results suggest that antivirulence strategies targeting fyuA+iucD strategists would be preferentially effective against CIPRE. coli in geographically diverse populations. This connection between virulence and resistance is unexpected, and the reason for it remains unclear.

Figure 6.

Siderophore genotypes as correlates of CIP resistance (CIPR). (a) CIPR rates among E. coli at Barnes-Jewish Hospital from 2000 to 2013 are shown. The gray bar corresponds to the collection period for the clinical isolates examined in this study. (b) Most CIPR urinary E. coli isolates are fyuA+iucD strategists, whereas (c) all fyuA+iroN strategists are CIPS.

The existence of stereotypical virulence strategists across multiple phylogenetic types (the main communities detected here contain both phylogenetic group B2 and non-B2 strains) in bacteriuric isolates suggests an underlying pathophysiologic basis for VF community composition. In the evolutionary paradigm, VFs with complementary activities are expected to possess a selective advantage, whereas a noncomplementary VF may confer a metabolic penalty.42 Pathogenic success in these bacteria may thus be a more qualitative phenomenon than the sum total of virulence factors alone (the “virulence score”) would suggest. The sex-selective strategists observed here raise the possibility that the iucD-associated VF community confers greater fitness for a male pathophysiologic niche such as prostate tissue. It is less clear why the same VF community is associated with antibiotic resistance, although this could be associated with distinctive antibiotic uses in male patients or occupation of a niche that facilitates resistance. Possible contributions from local circulating E. coli clones, plasmids, phages, or antibiotic use patterns to the results are also unclear. Much remains to be learned about the biology and therapeutic implications of the combinatorial strategists identified here. Although the VF genes assessed here are almost certainly an incomplete list, application of the mathematical approaches described here to more extensive genetic data from a geographically more diverse patient cohort would help to evaluate the interpretations above.

By resolving meaningful associative patterns from heterogeneous clinical isolates, contemporary exploratory tools such as network analysis offer significant advances over traditional monogenic analyses. Additionally, these approaches are insensitive to additive or synergistic VF combinations that enhance pathogen virulence or antagonistic combinations that reduce it. Whereas network community detection amplifies signal from noise to identify superstructures in the data, the complementary biclustering approach described here simultaneously identifies related E. coli strains and virulence factors that significantly interact. By offering a simplified relational superstructure of the data, they also account for the possibility of clonality in a complex pathogenic data set. It is notable that network analysis and biclustering identified VF communities that mirror the evolutionary relationships proposed above. Basically, network analysis identifies VF pairs that are most successful in the study population (i.e., most strongly associated with each other relative to chance) and progressively assembles these into an interrelated network based upon these pairwise interactions. In contrast, more restrictive methods such as PCA and hierarchical clustering (Figures S2 and S3) do not capture the interacting gene groups identified in this study. Analyzed with different tools, the choice of antivirulence targets is thus an extension of their evolutionary interrelationships. Targeting these synergistic combinations would lower selective pressure for antibiotic resistance and minimize the impact on commensal bacteria, presenting a major advance in infection pharmacotherapy.

Methods

Study Design, Data Collection, Laboratory Analyses, and Definitions

The samples were collected as part of a 1 year (August 1, 2009, to July 31, 2010) Washington University Institutional Review Board-approved prospective study of patients with E. coli bacteriuria (>5 × 104 colony-forming units (CFU)/mL) described by Marschall et al.20 These urine cultures were obtained as part of the clinical workup for these patients and were then processed at the hospital’s medical microbiology laboratory. Clinical isolates were retrieved directly from this laboratory once bacteriuric patients were identified in the hospital’s patient database. Strains without associated blood culture data were not excluded from this study. Briefly, clinical isolates were collected from male and female patients with significant bacteriuria. Bacterial DNA was extracted using a QIAamp DNA mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). DNA probes for virulence genes were developed as previously described20 by the molecular epidemiology laboratory at the University of Michigan’s School of Public Health, and the presence of these genes was determined by dot-blot hybridization using a previously described microarray system43 (Table 1). This method is based on established cDNA glass microarray fabrication and hybridization techniques that are modified by printing total bacterial genomic DNA on the slide. The hybridization signal is determined by both the target concentration in the spot and the quantity of the fluorescent tag carried by the probe, both of which were empirically optimized by Zhang et al.43 DNA concentration was controlled for in a separate quantification step, utilizing 16S rRNA PCR. Whereas the clinical isolate collection dates varied, laboratory processing and analysis were concentrated over a small number of defined sessions, each of which included appropriate controls.

The E. coli phylogenetic group was determined from hybridization results using the triple genotyping method of Clermont et al.44 Antimicrobial susceptibility was determined using disk diffusion tests (Kirby–Bauer). In this commonly used test, bacterial growth is observed in response to a standard concentration of a particular antibiotic. Resistance is defined by employing Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI; Wayne, PA, USA) standards for measuring the zone of inhibition around the antibiotic-impregnated disk and comparing it to a standard interpretation chart.45 Only three isolates qualified as moderately resistant by this measure (the rest were either resistant or susceptible) and were qualified as resistant for the purposes of this study. Bacteriuria was defined as ≥5 × 104 CFU/mL in noncatheterized patients and ≥5 × 103 CFU/mL in catheterized patients, as well as by using the patients’ documented urinary symptoms. Pyelonephritis was defined as the presence of flank pain and tenderness and/or fever; sepsis and sepsis-induced hypotension were defined using established clinical criteria. The Microbiology Laboratory at Barnes-Jewish Hospital provided clinical antibiogram data.

Network Analysis

The (bipartite) clinical-isolates-by-genes binary data array was projected onto two separate (unipartite) network representations, one each for the clinical isolates and for the VFs. The VF network, connected by similar co-occurrences across the clinical isolate population, was defined by statistically significant positive correlation coefficients between VF pairs. Statistical significance was determined by Fisher exact tests on 2 × 2 contingency tables; for each pair of genes the 2 × 2 contingency table of the number of expressed and not-expressed outcomes for each of these two genes was tabulated, and then a Fisher exact test was used to determine whether or not the two genes appeared independently within the population of clinical isolates, conditional on their observed marginal frequencies in the population. A 1.5% p value threshold (one-tailed on the right, without correction for multiple testing) was chosen to ensure that the resulting network of VFs was a single connected component. An edge was defined as present between any pair of positively correlated genes that satisfied the threshold, and then the positive weight of that edge was set by the correlation coefficient. To continue to respect the diversity of background VF expression frequencies, we define the network of clinical isolates in terms of the column-standardized version of the clinical-isolates-by-VFs data array; that is, each column is centered to zero and rescaled to unit variance. The resulting column-standardized matrix M yielded the full matrix of correlation coefficients between VFs through the expression MTM/(n – 1), where n is the number of clinical isolates. For symmetry, we defined the clinical isolates adjacency matrix, the (i,j) element of which indicates the presence and weight of the edge connecting nodes i and j, from the matrix product MMT, thresholding the elements to retain all positive elements of the resulting matrix product. We set the diagonals of both adjacency matrices to zero (no self-loops).

Community detection of the clinical isolate and VF networks was performed by maximizing modularity with a resolution parameter, by a generalized implementation of the Louvain method followed by Kernighan–Lin node-swapping steps.21,22,46,47 Networks were partitioned into various numbers of communities by varying the resolution parameter (γ index, Figure S4). This parameter appears directly in the definition of modularity and optimizes community selection. Through this procedure, a collection of nested VF network partitions was identified (as visualized in the main text). For the network of CIs, closely similar four-community partitions were identified in a range of gamma values straddling its default value (γ = 1.0), so we restricted our attention to a four-community partition found at that default resolution.

Biclustering

Biclustering is a popular statistical tool for exploratory analysis of high-dimensional data.48 Given a matrix of genes by isolates, the goal of biclustering is to group the rows and columns to find “dense” regions of the matrix, that is, groups of VFs similarly expressed by subsets of isolates. The expression profile is a binary structure where values for each clinical isolate indicate expression of a VF (0 = absence, 1 = presence). A binary version of large average submatrices (LAS) was used to exhaustively search the 337 × 16 condition matrix for all statistically significant biclusters of large average expression.23

This method operates in an iterative-residual fashion and is driven by a Bonferroni-based significance score that trades off between submatrix size and average value. The method identified statistically significant large average biclusters, in the sense that the VFs are expressed across the collection of clinical isolates more often than expected within the entire population. The significance of an identified k × l bicluster U is measured through a binary score function

where F(τ;kl;1 – p) gives the null probability that the kl entries of U have τ or more 1s. The probability inside the logarithm is a Bonferroni-corrected p value associated with observing a submatrix with an average at least as large as U. The algorithm was set to find biclusters with score S(U) ≥100.

Statistical Analysis

A multivariate logistic regression model was used to identify covariates significantly associated with antibiotic resistance. The fitted model included indicator (0/1) covariates for sex, community containment, bicluster containment, and siderophore content. The covariates with statistically significant coefficients (p value < 0.10) for each antibiotic (CIP and TMP/S) are shown in Table 3. A nested models approach was used to determine the significance of variability in antibiotic resistance (CIP and TMP/S) explained by the inclusion of covariates describing sex, community containment, bicluster containment, and siderophore type. The null model contained only the mean response for resistance to CIP and TMP/S, respectively. Sequentially, each of the above covariates was added to the null model, and the variability explained in the model was recorded. To test the significance of the added covariate type, an analysis of deviance was employed wherein a χ2 test was used to test the reduction in deviance from the null model. The models and test results are shown in Table 3. PCA and hierarchical analysis were conducted using MATLAB.

Acknowledgments

We thank B. Foxman and L. Zhang (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) for dot-blot hybridization analysis. We also thank C. A. Burnham, E. Casabar, and the Barnes-Jewish Hospital Microbiology Laboratory for assistance with clinical isolates and antibiotic resistance records. J.P.H. holds a Career Award for Medical Scientists from the Burroughs-Wellcome Fund and acknowledges NIH Grants R01DK099534 and P50DK064540. J.M. acknowledges NIH Grants UL1RR024992, KL2RR024994, and BIRCWH 5K12HD001459-13. J.D.W. acknowledges NSF Grant DMS-1310002. P.J.M. acknowledges support from the James S. McDonnell Foundation 21st Century Science Initiative – Complex Systems Scholar Award Grant 220020315. J.P.H. and K.S.C. additionally acknowledge the Longer Life Foundation and the Center for Women’s Infectious Disease Pilot Research Project Grant.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.5b00022.

Author Present Address

△ Department of Mathematics and Statistics, the University of San Francisco

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Dethlefsen L.; Relman D. A. (2011) Incomplete recovery and individualized responses of the human distal gut microbiota to repeated antibiotic perturbation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108 (Suppl. 1), 4554–4561. 10.1073/pnas.1000087107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekirov I.; Tam N. M.; Jogova M.; Robertson M. L.; Li Y.; Lupp C.; Finlay B. B. (2008) Antibiotic-induced perturbations of the intestinal microbiota alter host susceptibility to enteric infection. Infect. Immun. 76, 4726–4736. 10.1128/IAI.00319-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho J.; Tambyah P. A.; Paterson D. L. (2010) Multiresistant Gram-negative infections: a global perspective. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 23, 546–553. 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32833f0d3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta K.; Hooton T. M.; Stamm W. E. (2001) Increasing antimicrobial resistance and the management of uncomplicated community-acquired urinary tract infections. Ann. Intern. Med. 135, 41–50. 10.7326/0003-4819-135-1-200107030-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litwin M. S.; Saigal C. S.; Yano E. M.; Avila C.; Geschwind S. A.; Hanley J. M.; Joyce G. F.; Madison R.; Pace J.; Polich S. M.; Wang M. (2005) Urologic diseases in America Project: analytical methods and principal findings. J. Urol. 173, 933–937. 10.1097/01.ju.0000152365.43125.3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown K. A.; Khanafer N.; Daneman N.; Fisman D. N. (2013) Meta-analysis of antibiotics and the risk of community-associated Clostridium difficile infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57, 2326–2332. 10.1128/AAC.02176-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischbach M. A.; Walsh C. T. (2009) Antibiotics for emerging pathogens. Science 325, 1089–1093. 10.1126/science.1176667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiles T. J.; Kulesus R. R.; Mulvey M. A. (2008) Origins and virulence mechanisms of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 85, 11–19. 10.1016/j.yexmp.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wandersman C.; Delepelaire P. (2004) Bacterial iron sources: from siderophores to hemophores. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 58, 611–647. 10.1146/annurev.micro.58.030603.123811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelhart C. A.; Aldrich C. C. (2013) Synthesis of chromone, quinolone, and benzoxazinone sulfonamide nucleosides as conformationally constrained inhibitors of adenylating enzymes required for siderophore biosynthesis. J. Org. Chem. 78, 7470–7481. 10.1021/jo400976f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukacik P.; Barnard T. J.; Keller P. W.; Chaturvedi K. S.; Seddiki N.; Fairman J. W.; Noinaj N.; Kirby T. L.; Henderson J. P.; Steven A. C.; Hinnebusch B. J.; Buchanan S. K. (2012) Structural engineering of a phage lysin that targets Gram-negative pathogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109, 9857–9862. 10.1073/pnas.1203472109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng T.; Nolan E. M. (2014) Enterobactin-mediated delivery of beta-lactam antibiotics enhances antibacterial activity against pathogenic Escherichia coli. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 9677–9691. 10.1021/ja503911p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorska A.; Sloderbach A.; Marszall M. P. (2014) Siderophore-drug complexes: potential medicinal applications of the “Trojan horse” strategy. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 35, 442–449. 10.1016/j.tips.2014.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pramanik A.; Stroeher U. H.; Krejci J.; Standish A. J.; Bohn E.; Paton J. C.; Autenrieth I. B.; Braun V. (2007) Albomycin is an effective antibiotic, as exemplified with Yersinia enterocolitica and Streptococcus pneumoniae. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 297, 459–469. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cusumano C. K.; Pinkner J. S.; Han Z.; Greene S. E.; Ford B. A.; Crowley J. R.; Henderson J. P.; Janetka J. W.; Hultgren S. J. (2011) Treatment and prevention of urinary tract infection with orally active FimH inhibitors. Sci. Transl. Med. 3, 109ra115. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brumbaugh A. R.; Smith S. N.; Mobley H. L. (2013) Immunization with the yersiniabactin receptor, FyuA, protects against pyelonephritis in a murine model of urinary tract infection. Infect. Immun. 81, 3309–3316. 10.1128/IAI.00470-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langermann S.; Ballou W. R. (2003) Development of a recombinant FimCH vaccine for urinary tract infections. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 539, 635–648. 10.1007/978-1-4419-8889-8_41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clatworthy A. E.; Pierson E.; Hung D. T. (2007) Targeting virulence: a new paradigm for antimicrobial therapy. Nat. Chem. Biol. 3, 541–548. 10.1038/nchembio.2007.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman J. A.; Schreiber H. L. t.; Hooton T. M.; Hultgren S. J. (2013) From physiology to pharmacy: developments in the pathogenesis and treatment of recurrent urinary tract infections. Curr. Urol. Rep. 14, 448–456. 10.1007/s11934-013-0354-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marschall J.; Zhang L.; Foxman B.; Warren D. K.; Henderson J. P.; Program C. D. C. P. E. (2012) Both host and pathogen factors predispose to Escherichia coli urinary-source bacteremia in hospitalized patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 54, 1692–1698. 10.1093/cid/cis252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortunato S. (2010) Community detection in graphs. Phys. Rep. 486, 75–174. 10.1016/j.physrep.2009.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Porter M. A.; Onnela J. P.; Mucha P. J. (2009) Communities in networks. Notices AMS 56, 1082–1097,. 1164–1066. [Google Scholar]

- Shabalin A. A.; Weigman V. J.; Perou C. M.; Nobel A. B. (2009) Finding large average submatrices in high dimensional data. Ann. Appl. Stat. 3, 985–1012. 10.1214/09-AOAS239. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J. R.; Kuskowski M. A.; Gajewski A.; Soto S.; Horcajada J. P.; Jimenez de Anta M. T.; Vila J. (2005) Extended virulence genotypes and phylogenetic background of Escherichia coli isolates from patients with cystitis, pyelonephritis, or prostatitis. J. Infect. Dis. 191, 46–50. 10.1086/426450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi K. S.; Hung C. S.; Crowley J. R.; Stapleton A. E.; Henderson J. P. (2012) The siderophore yersiniabactin binds copper to protect pathogens during infection. Nat. Chem. Biol. 8, 731–736. 10.1038/nchembio.1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh E. I.; Hung C. S.; Parker K. S.; Crowley J. R.; Giblin D. E.; Henderson J. P. (2015) Metal selectivity by the virulence-associated yersiniabactin metallophore system. Metallomics 7, 1011–1022. 10.1039/C4MT00341A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields-Cutler R. R.; Crowley J. R.; Hung C. S.; Stapleton A. E.; Aldrich C. C.; Marschall J.; Henderson J. P. (2015) Human urinary composition controls siderocalin’s antibacterial activity. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 15949–15960. 10.1074/jbc.M115.645812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson J. P.; Crowley J. R.; Pinkner J. S.; Walker J. N.; Tsukayama P.; Stamm W. E.; Hooton T. M.; Hultgren S. J. (2009) Quantitative metabolomics reveals an epigenetic blueprint for iron acquisition in uropathogenic Escherichia coli. PLoS Pathog. 5, e1000305. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brumbaugh A. R.; Mobley H. L. (2012) Preventing urinary tract infection: progress toward an effective Escherichia coli vaccine. Expert Rev. Vaccines 11, 663–676. 10.1586/erv.12.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalhoff A. (2012) Global fluoroquinolone resistance epidemiology and implictions for clinical use. Interdiscip. Perspect. Infect. Dis. 2012, 976273. 10.1155/2012/976273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y.; Ma Y.; Zhao Q.; Wang L.; Guo L.; Ye L.; Zhang Y.; Yang J. (2012) Similarity and divergence of phylogenies, antimicrobial susceptibilities, and virulence factor profiles of Escherichia coli isolates causing recurrent urinary tract infections that persist or result from reinfection. J. Clin. Microb. 50, 4002–4007. 10.1128/JCM.02086-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piatti G.; Mannini A.; Balistreri M.; Schito A. M. (2008) Virulence factors in urinary Escherichia coli strains: phylogenetic background and quinolone and fluoroquinolone resistance. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46, 480–487. 10.1128/JCM.01488-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno E.; Prats G.; Sabate M.; Perez T.; Johnson J. R.; Andreu A. (2006) Quinolone, fluoroquinolone and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole resistance in relation to virulence determinants and phylogenetic background among uropathogenic Escherichia coli. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 57, 204–211. 10.1093/jac/dki468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C. S.; Kim M. E.; Cho Y. H.; Cho I. R.; Lee G. (2010) Virulence characteristics and phylogenetic background of ciprofloxacin resistant Escherichia coli in the urine samples from Korean women with acute uncomplicated cystitis. J. Korean Med. Sci. 25, 602–607. 10.3346/jkms.2010.25.4.602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J. R.; Kuskowski M. A.; O’Bryan T. T.; Colodner R.; Raz R. (2005) Virulence genotype and phylogenetic origin in relation to antibiotic resistance profile among Escherichia coli urine sample isolates from Israeli women with acute uncomplicated cystitis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49, 26–31. 10.1128/AAC.49.1.26-31.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katouli M.; Brauner A.; Haghighi L. K.; Kaijser B.; Muratov V.; Mollby R. (2005) Virulence characteristics of Escherichia coli strains causing acute cystitis in young adults in Iran. J. Infect. 50, 312–321. 10.1016/j.jinf.2004.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olesen B.; Frimodt-Moller J.; Leihof R. F.; Struve C.; Johnston B.; Hansen D. S.; Scheutz F.; Krogfelt K. A.; Kuskowski M. A.; Clabots C.; Johnson J. R. (2014) Temporal trends in antimicrobial resistance and virulence-associated traits within the Escherichia coli sequence type 131 clonal group and its H30 and H30-Rx subclones, 1968 to 2012. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58, 6886–6895. 10.1128/AAC.03679-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olesen B.; Scheutz F.; Menard M.; Skov M. N.; Kolmos H. J.; Kuskowski M. A.; Johnson J. R. (2009) Three-decade epidemiological analysis of Escherichia coli O15:K52:H1. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47, 1857–1862. 10.1128/JCM.00230-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platell J. L.; Trott D. J.; Johnson J. R.; Heisig P.; Heisig A.; Clabots C. R.; Johnston B.; Cobbold R. N. (2012) Prominence of an O75 clonal group (clonal complex 14) among non-ST131 fluoroquinolone-resistant Escherichia coli causing extraintestinal infections in humans and dogs in Australia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56, 3898–3904. 10.1128/AAC.06120-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu S.; Mukherjee S. K.; Hazra A.; Mukherjee M. (2013) Molecular characterization of uropathogenic Escherichia coli: nalidixic acid and ciprofloxacin resistance, virulent factors and phylogenetic background. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 7, 2727–2731. 10.7860/JCDR/2013/6613.3744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaureguy F.; Carbonnelle E.; Bonacorsi S.; Clec’h C.; Casassus P.; Bingen E.; Picard B.; Nassif X.; Lortholary O. (2007) Host and bacterial determinants of initial severity and outcome of Escherichia coli sepsis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 13, 854–862. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv H.; Hung C. S.; Henderson J. P. (2014) Metabolomic analysis of siderophore cheater mutants reveals metabolic costs of expression in uropathogenic Escherichia coli. J. Proteome Res. 13, 1397–1404. 10.1021/pr4009749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L.; Srinivasan U.; Marrs C. F.; Ghosh D.; Gilsdorf J. R.; Foxman B. (2004) Library on a slide for bacterial comparative genomics. BMC Microbiol. 4, 12. 10.1186/1471-2180-4-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clermont O.; Bonacorsi S.; Bingen E. (2000) Rapid and simple determination of the Escherichia coli phylogenetic group. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66, 4555–4558. 10.1128/AEM.66.10.4555-4558.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLSI. (2006) Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, M100-S16, Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 16th Informational Supplement, Wayne, PA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Jutla I. S., Lucas G. S., and Mucha P. J. (2011) A generalized louvain method for community detection implemented in Matlab. http://netwiki.amath.unc.edu/GenLouvain.

- Reichardt J.; Bornholdt S. (2006) Statistical mechanics of community detection. Phys. Rev. E 74, 016110. 10.1103/PhysRevE.74.016110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madeira S. C.; Oliveira A. L. (2004) Biclustering algorithms for biological data analysis: a survey. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinf. 1, 24–45. 10.1109/TCBB.2004.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.