Abstract

Delivery systems other than in-office therapist-led treatments are needed to address treatment barriers such as accessibility, efficiency, costs, and parents wanting an active role in helping their child. To address these barriers, stepped care trauma focused-cognitive behavioral therapy (SC-TF-CBT) was developed as a parent-led, therapist-assisted therapy that occurs primarily at-home so that fewer in-office sessions are required. The current study examines caregivers’ perceptions of parent-led (SC-TF-CBT) and therapist-led (TF-CBT) treatment. Participants consisted of 52 parents/care-givers (25–68 years) of young trauma-exposed children (3–7 years) who were randomly assigned to SC-TF-CBT (n = 34) or to TF-CBT (n = 18). Data were collected at mid-and post-treatment via interviews inquiring about what participants liked, disliked, found most helpful, and found least helpful about the treatment. Results indicated that parents/caregivers favored relaxation skills, affect modulation and expression skills, the trauma narrative, and parenting skills across both conditions. The majority of parents/caregivers in SC-TF-CBT favored the at-home parent–child meetings and the workbook that guides the parent-led treatment, and there were suggestions for improving the workbook. Reported disliked and least helpful aspects of treatments were minimal across conditions, but themes that emerged that will need further exploration included the content and structure, and implementation difficulties for both conditions. Collectively, these results highlight the positive impact that a parent-led, therapist-assisted treatment could have in terms of providing caregivers with more tools to help their child after trauma and reduce barriers to treatment.

Keywords: Stepped care, Parent-led therapy, Children, Posttraumatic stress, Trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy

Introduction

Trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy (TF-CBT) is an evidence-based treatment for children, including young children, who are experiencing posttraumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) after a traumatic event (Cary and McMillen 2012; Cohen et al. 2004; de Arellano et al. 2014; Scheeringa et al. 2007). TF-CBT, a therapist-led treatment, is being widely disseminated (Cohen and Mannarino 2008; Ebert et al. 2012; Jensen et al. 2014; Murray et al. 2013; Sigel et al. 2013). However, therapies that involve weekly therapist-led treatment can present barriers to treatment such as costs, inconveniences, stigma, limited availability of trained therapists (Bringewatt and Gershoff 2010), and parents’ wanting to solve their child’s problem independently (Thurston and Phares 2008). One approach to addressing treatment barriers for children with PTSS is to provide TF-CBT as a stepped care intervention where Step One is parent-led treatment at-home with minimal therapist support and Step Two, which consists of standard therapist-led TF-CBT, is only provided to children needing more intensive treatment. Stepped Care TF-CBT (SC-TF-CBT) has been developed (Salloum et al. 2013) and undergone pilot feasibility and efficacy trials (Salloum and Storch 2011; Salloum et al. 2014), but parents’ perception of leading their child’s treatment has not been examined.

Step One within SC-TF-CBT (Salloum et al. 2013) includes similar treatment components as standard TF-CBT such as psychoeducation, parenting skills, relaxation, affective expression and modulation, trauma narrative, cognitive processing, in vivo mastery, and conjoint child-parent sessions (Cohen et al. 2006). What is different about Step One compared to standard TF-CBT is that the parent leads the trauma-focused treatment components at-home, without the therapist, using a parent–child workbook called Stepping Together (Salloum et al. 2009) as a treatment guide. The workbook is based on the therapist treatment manual for Preschool PTSD Treatment (Scheeringa et al. 2010) which consists of building coping skills and having the child complete trauma-focused exposures. In vivo exposure exercises are used in standard TF-CBT as needed, whereas in Step One, there are six parent–child at-home meetings that focus on drawing the trauma narrative, imagining it, and having the child complete an exposure to a trauma reminder. The parent and child only meet with the therapist every other week over a 6 week period where they receive sections of the book, and the therapist provides technical assistance to the parent in terms of establishing exposures for the parent and child to complete at-home. Both Stepped Care and standard TF-CBT include the parent and child in treatment.

Many mental health treatments for childhood disorders include both the parent and child in treatment. In fact, findings from three randomized clinical trials (RCT) suggest that while parent-only treatment for child sexual abuse is helpful in terms of increasing parenting skills and addressing child externalizing behavior, child participation in therapy results in greater improvements in child PTSD than parent-only treatment (Deblinger et al. 1996, 2001; King et al. 2000). A study using focus groups with therapists, parents, and children (ages 5–13) who were receiving treatment at community outpatient centers due to disruptive behavioral problems suggests that therapists and parents wanted more involvement and support from each other in treatment and the children wanted their parents more involved in their therapy (Baker-Ericzen et al. 2013). The one qualitative study on children’s (ages 11–17) perceptions of TF-CBT found that more than half of the children preferred to talk with thetherapist about the trauma rather thantheir parent, with some youth suggesting that it may be too difficult for the parent to hear about the youth’s traumatic event. Most youth stated that it was alright for the therapist to share with the parent what the child was talking about in the sessions. Parents’ perceptions of involvement in their child’s treatment were not examined (Dittmann and Jensen 2014). Taken together, these studies raise questions about parents’ perception of leading their child’s trauma treatment in terms of their perceptions about the limited therapist support and working directly with the child to process the traumatic event. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to describe and compare parents’ experiences of participating in either the parent leading TF-CBT at-home (e.g., Step One) or the therapist leading TF-CBT in-office. Specifically, parents’ likes and dislikes as well as what they found the most and least helpful about either participating in Step One or standard TF-CBT were examined. Suggestions for improvements were also explored.

Method

Participants

Data for this study were part of a RCT where parent–child dyads were randomly assigned (2:1) to receive either SC-TF-CBT (n = 34) or TF-CBT (n = 18). The trial occurred at a community-based setting in a large metropolitan area in the United States. To participate in the RCT, children (ages 3–7) had to have at least five DSM-PTSD symptoms and parents and children had to be able to comprehend the treatment and follow instructions in English. For the current study, participants were excluded if they did not participate in the qualitative interview after either the mid- or post-treatment assessment. Only one parent–child dyad assigned to SC-TF-CBT was excluded for the current study due to dropping out before the mid-treatment interview. Results from the RCT study suggest child improvements occurred at the same rate in both conditions over time (e.g., post and 3 month follow-up) in PTSS, severity and externalizing and externalizing symptoms. There were no differences in parent-reported expectations and credibility of treatment and satisfaction. SC-TF-CBT was not inferior to TF-CBT for all child outcomes, although non-inferiority was not supported for externalizing symptoms. Costs were 51.3 % lower for children in SC-TF-CBT compared to TF-CBT (Salloum et al. 2015).

Participants consisted of 52 parents/caregivers (25–68 years, M = 33.1, SD = 8.44) of trauma-exposed young children (3–7 years, M = 7.17, SD = 1.4) with 34 assigned to SC-TF-CBT and 18 assigned to TF-CBT. Table 1 provides demographic information about the sample. Since the four relative caregivers were in the role of parent to the participating child and were leading the child’s treatment, we use the word parent in the following sections. The children’s index traumas as endorsed by the caregivers were as follows: 18 domestic violence (34.6 %), 17 sexual abuse (32.7 %), 6 death of a loved one/traumatic grief (11.5 %), 3 accident (5.8 %), 2 physical abuse (3.8 %), 1 kidnapping (1.9 %), 1 child removed from home (1.9 %), 1 child witnessed arrest (1.9 %), 1 victim of crime (1.9 %), 1 illness/medical (1.9 %), and 1 community violence (1.9 %). The vast majority (82.7 %) of children experienced poly-trauma and the mean number of traumatic events was 2.69 (SD = 1.15). Of the 34 assigned to SC-TF-CBT, 22 (64.7 %) responded after Step One.

Table 1. Demographics of participants by condition (N = 52).

| Characteristic | Stepped care (n = 34) n (%) |

Standard (n = 18) n (%) |

Total (N = 52) n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Child’s gender | |||

| Male | 19 (55.9) | 8 (44.4) | 27 (51.9) |

| Female | 15 (44.1) | 10 (55.6) | 25 (48.1) |

| Child’s ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic or Latino | 14 (41.2) | 10 (55.6) | 24 (46.2) |

| Not Hispanic/Latino | 20 (58.8) | 8 (44.4) | 28 (53.8) |

| Child’s race | |||

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 1 (2.9) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.9) |

| African American | 6 (17.6) | 8 (44.4) | 14 (26.9) |

| White | 24 (70.6) | 9 (50) | 33 (63.5) |

| Mixed race | 3 (8.8) | 1 (5.6) | 4 (7.7) |

| Identity of parent | |||

| Biological mother | 29 (86.5) | 16 (88.9) | 45 (86.5) |

| Biological father | 3 (8.8) | 0 (0) | 3 (5.8) |

| Grandmother | 2 (5.9) | 0 (0) | 2 (3.8) |

| Great aunt | 0 (0) | 1 (5.6) | 1 (1.9) |

| Aunt | 0 (0) | 1 (5.6) | 1 (1.9) |

| Parent’s ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic or Latino | 11 (32.4) | 9 (50) | 20 (38.5) |

| Not Hispanic/Latino | 23 (67.6) | 9 (50) | 32 (61.5) |

| Parent’s race | |||

| American Indian/Alaskan native | 0 (0) | 2 (11.1) | 2 (3.8) |

| African American | 6 (17.6) | 6 (33.3) | 12 (23.1) |

| White | 28 (82.4) | 10 (55.6) | 38 (73.1) |

| Household income | |||

| 0–9999 | 4 (11.8) | 7 (38.9) | 11 (21.2) |

| 10,000–24,999 | 9 (26.5) | 5 (27.8) | 14 (26.9) |

| 25,000–34,999 | 11 (32.4) | 1 (5.6) | 12 (23.1) |

| 35,000–49,999 | 4 (11.8) | 0 (0) | 4 (7.7) |

| 50,000 and above | 6 (17.6) | 5 (27.8) | 11 (21.2) |

| Parent employed | |||

| Yes | 22 (64.7) | 10 (55.6) | 32 (61.5) |

| Parent in treatment | |||

| Yes | 6 (17.6) | 5 (27.8) | 11 (21.2) |

| No | 28 (82.4) | 13 (72.2) | 41 (78.8) |

Since the relative caregivers were in the role of parent and led the child’s treatment, the term parent is used

Procedures

The current study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of South Florida. Written consent to participate in the RCT was obtained from all parents/caregivers. For the current study, all of the participants consented to have the interview audiotaped except for one parent who participated in SC-TF-CBT. In this case the interviewer read back to the participant her responses to clarify that what was written was complete and accurate.

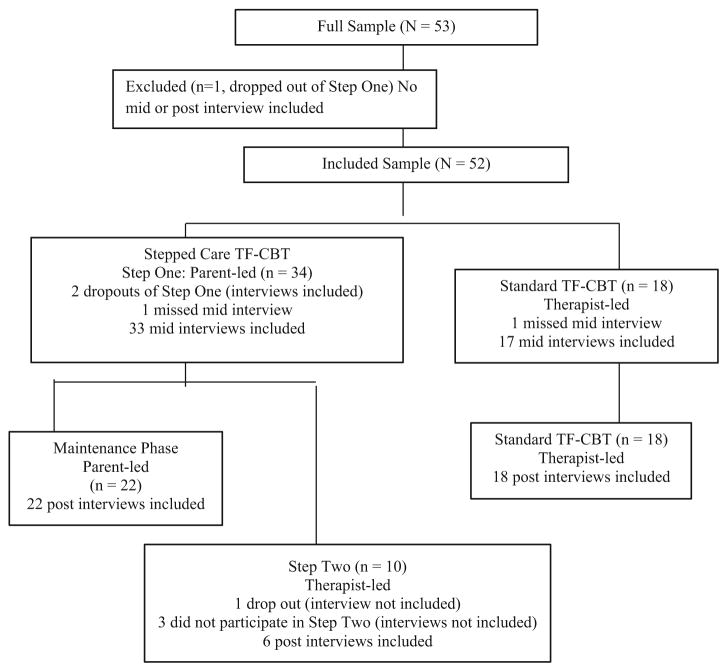

A total of 96 interviews (approximately 10–15 min) were conducted independently by the second and third authors, neither of whom provided treatment (see Fig. 1). Of the 34 participants in SC-TF-CBT, the following interviews occurred: 33 interviews after Step One, 22 occurred after maintenance phase and 6 after Step Two. One SC-TF-CBT participant missed the mid-treatment interview, and another participant missed the post-treatment interview. There were non-early responders who participated at the mid-treatment interview but did not participate in Step Two and thus were not able to provide feedback about Step Two. Of the 18 participants in TF-CBT, 17 mid-treatment interviews occurred after session 6, and 18 occurred at the end of TF-CBT. One TF-CBT caregiver missed the mid-treatment interview but completed the post-treatment interview. The interviews occurred after parents/caregivers completed an outcome assessment packet for the RCT and compensation ($50.00 each) was provided after both the mid- and post-treatment assessments.

Fig. 1.

Record of interviews included after parent-led and therapist-led treatment

Stepped Care TF-CBT

Step One is a parent-led, therapist-assisted treatment wherein each parent–child dyad participates in three in-office therapist-led sessions. In each of these sessions, the parent received parts of a workbook called Stepping Together that they used to guide treatment during their 11 parent–child meetings at-home. Some of the activities in Stepping Together involved learning relaxation tools (e.g., deep breathing, muscle relaxation, and safe place imagery) and feelings identification and expression. A “feelings score” was used to help the child identify the intensity of a feeling he/she was experiencing. Other components of Stepping Together involved the child developing a trauma narrative and identifying trauma reminders through a “scary ladder” (e.g., fear hierarchy). This hierarchy of trauma reminders was then used to facilitate exposures that were completed through drawing them in the workbook, imagining them, and “next steps” (e.g., in vivo exposures). The first part of the book, called “Just for You,” provides an overview of the treatment and helps the parent prepare to provide the treatment by providing psychoeducation and exploring social supports and his/her own feelings. During in-office meetings, the therapist provided to the parent a general orientation to Step One, technical assistance for relaxation strategies and “next steps,” and support. Weekly telephone support (10–15 min per call) was provided to each parent by the therapist to discuss progress, problem-solve, and provide support. Parents were encouraged to access a private website where they could watch demonstrations of relaxation exercises and exposures, and receive additional psychoeducational information about childhood trauma.

After completion of Step One, parents completed an assessment with a blinded evaluator to determine if they met responder status. Responder status was based on the child having three or fewer PTSD symptoms as determined by the Diagnostic Infant and Preschool Assessment (DIPA; Scheeringa and Haslett 2010), or a total score of 40 or less on the Trauma Symptom Checklist for Young Children (TSCYC; Briere et al. 2001) and a rating of 3 (improved), 2 (much improved), or 1 (free of symptoms) on the Clinical Global Impression-Improvement Scale (Guy 1976). If the child met responder status, the parent and child entered into the maintenance phase which consisted of a 6 week period for the parent and child to continue to practice the tools and skills (relaxation skills, feelings score use, and parenting skills) and to continue to meet weekly to strengthen the parent–child relationship. If the child did not meet responder status, the child would step up to Step Two which consisted of 9 (90 min) in-office therapist-led TF-CBT sessions. After either completion of the maintenance phase or Step Two, parents completed another assessment to determine post-treatment outcomes and perceptions of treatment.

Standard TF-CBT

Similar to Cohen et al. (2004), TF-CBT consisted of 12 weekly sessions in-office (90 min each) where the following treatment components are addressed: psychoeducation; parenting skills; relaxation skills; affect expression and modulation; cognitive coping; trauma narrative; in vivo exposure, which was optional depending on need; conjoint child-parent sessions; enhancing safety; and problem-solving skills (Cohen et al. 2006).

Treatment Fidelity

Four community-based post-masters therapists provided treatment in both conditions. Their experience consisted of 5 months, 11 months, 3 years 3 months, and 14 years 10 months. In Step One there were a total of 89 therapist-led sessions (M = 2.65, SD = .95) and 63 Step Two therapist-led sessions (M = 5.25, SD = 4.85). In TF-CBT, there were 199 therapist-led sessions (M = 11.06, SD = 2.6). Therapists completed treatment adherence checklists after every therapist-led session. The third author, a licensed mental health professional who was also the project coordinator, randomly reviewed 42.86 % of Step One sessions, 28.57 % of Step Two sessions and 31.71 % of TF-CBT sessions. Agreement between ratings was above 95 % for all treatments.

Measures

The interview guide consisted of six open-ended questions assessing the parents’/caregivers’ perception of the treatment their child was assigned to. The questions asked included: (1) what did you like about the program? (2) what didn’t you like about the program?, (3) what was the most helpful?, (4) what was the least helpful?, and (5) what suggestions do you have for improving the program? At the mid-treatment interview, participants were asked these questions in reference to Step One or to the first six sessions of TF-CBT and at the post-treatment interview, they were asked these questions in reference to the maintenance phase, Step Two, or the last six sessions of TF-CBT.

Data Analysis

This qualitative study about the experiences of parents/caregivers leading or participating in their child’s trauma-focused treatment seeks to understand this phenomenon from the perspective of the participating parents/caregivers. Thus, the methods were based on the phenomenological tradition (Moustakas 1994). The second author transcribed all of the transcripts and the third author listened to the audio and reviewed the transcripts for accuracy. Since the maintenance phase was also parent-led, we combined SC-TF-CBT transcripts from the mid- and post-treatment interviews. Similarly, the transcripts for the mid- and post-treatment interviews for TF-CBT were combined. The first, second, and third authors reviewed all transcripts. The first author is one of the developers of SC-TF-CBT and certified in TF-CBT, and provided clinical supervision for both treatments in the RCT. However, to minimize bias, the second and third authors coded all of the data since neither one of these authors were involved clinically with the treatment. The first three authors developed an initial code book based on the treatment components of Step One, maintenance phase, and TF-CBT (e.g., relaxation, parenting skills, trauma narrative, phone support).

Four transcripts (two from Step One and maintenance phase and two from TF-CBT) were coded independently and discrepancies were discussed. The code book was revised based on the agreement in definition and examples between the coders. An additional nine transcripts were reviewed until above 90 % agreement was met (94.4 % met). To ensure high rater-agreement, an additional transcript was coded and there was 100 % agreement. Both coders then coded all of the transcripts independently and discrepancies were addressed via discussion and consensus. The first author, who is trained in qualitative data analysis, provided consultation to the second and third author throughout the coding process. In one instance, the first author assisted with obtaining consensus in coding text for TF-CBT. Specifically, the second and third authors were unclear as to how to code a statement regarding parental involvement. The confusion arose from the code involvement as this code was listed under the main theme of parent-led, regardless of treatment condition. Since the parent-led theme was not applicable for TF-CBT, the code book was updated to include involvement in TF-CBT under the parent–child meetings/conjoint sessions theme (because TF-CBT parents’ involvement took place during the conjoint sessions) and that theme was renamed parent–child meeting/conjoint sessions and involvement. All final codes were entered into an Excel database and sorted by questions (e.g., liked/disliked, most/least helpful, and comments). The first three authors developed themes based on the codes and, when appropriate, subthemes were developed.

To make sure that all perspectives were captured, we conducted three exploratory analyses. First, differences in themes between parents/caregivers whose children were early responders of Step One (n = 22) and non-early responders of Step One were compared (n = 10 non-responders plus 2 dropouts of Step One). Second, six interviews of parent/caregivers who stepped up to Step Two were explored in terms of differences in themes compared to their Step One responses. Third, we reviewed the coded data from the two cases that dropped out of Step One to explore if any new codes were recorded.

Results

In the following discussion of results, we provide the frequency of parents who “liked and/or found most helpful” and “disliked and/or found least helpful” the various components and aspects of treatment. The reported frequencies in the discussion and Table 2 indicate that the specific responses were classified under the identified theme; it does not mean that the remaining percentage of parents indicated the opposite. The specific subthemes of parents’ perceptions are also discussed. Since the components in the maintenance phase were parent-led and included some of the same components as Step One, the themes expressed during the interviews after the maintenance phase (i.e., post-treatment interviews) were merged with Step One participants’ perceptions. Therefore, the themes reported for parent-led treatment include interviews from early responders and non-early responders of Step One and themes from the maintenance phase (now referred to as Step One parent/caregivers); which are the themes all about the parent-led treatment (Step One and maintenance phase). The unique components and aspects of Step One are presented first (e.g., Stepping Together Workbook, parent-led, phone support), followed by the treatment components (e.g., relaxation, parent–child meetings/conjoint sessions, parenting skills, trauma narrative and exposures, affect expression and modulation, cognitive coping, safety and psychoeducation and homework), general aspects of treatment (e.g., therapists, structure/content, implementation difficulty, and liking the program and for Step One only, schedule and review of progress), suggestions and an exploratory analysis.

Table 2. Parents’ perceptions of Step One, treatment components and aspects of treatment in Step One (N = 34) and standard TF-CBT (N = 18).

| Themes | Step One Liked/found helpful |

Step One Disliked/least helpful |

Standard TF-CBT Liked/found helpful |

Standard TF-CBT Disliked/least helpful |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Step One only | ||||||||

| Stepping Together Workbook | 21 | 61.8 | 8 | 23.5 | – | – | – | – |

| Parent-led | 16 | 47.1 | 5 | 14.7 | – | – | – | – |

| Phone support | 7 | 20.6 | 0 | 0 | – | – | – | – |

| Components | ||||||||

| Relaxation | 20 | 58.8 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 50 | 0 | 0 |

| Parent–child meetings/conjoint sessions | 17 | 50 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 16.7 | 0 | 0 |

| Parenting skills | 11 | 32.3 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 55.6 | 0 | 0 |

| Trauma narrative and exposures | 14 | 41.2 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 44.4 | 0 | 0 |

| Affect expression and modulation | 14 | 41.2 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 38.9 | 0 | 0 |

| Cognitive coping | 6 | 17.6 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 11.1 | 0 | 0 |

| Safety | 2 | 5.9 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 22.2 | 0 | 0 |

| Psychoeducation | 2 | 5.9 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 16.7 | 0 | 0 |

| Homework | – | – | – | – | 3 | 16.7 | 0 | 0 |

| Aspects of treatment | ||||||||

| Therapist | 18 | 52.9 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 88.9 | 0 | 0 |

| Content and/or structure | 10 | 29.4 | 5 | 14.7 | 10 | 55.6 | 4 | 22.2 |

| Implementation difficulty | – | – | 9 | 26.5 | – | – | 3 | 16.7 |

Unique Components and Aspects of Step One

Twenty-one parents (61.8 %) in Step One reported liking and/or finding helpful the Stepping Together Workbook whereas eight parents (23.5 %) reported disliking and/or finding it least helpful. Some of the comments regarding liking/finding helpful the Stepping Together Workbook were regarding the book having clear directions, being user friendly, repetition, and review of progress. One of the parents that mentioned liking/finding helpful the clear directions stated the following, “The workbook was great and it was easy to read and it wasn’t small print and it was really laid out for you and so easy to be able to take home and reference it and have it right there.” Another parent (of a 4 year old child) indicated that the workbook was developmentally geared toward her child’s age, “And just the way it (referring to the book) was geared for her age.” Regarding finding the review of progress helpful, one parent stated, “I think her actually seeing it on paper and being able to go back through the little scenario when we did the review. It seemed to be helpful to her to remember everything.” Comments regarding disliking/finding least helpful the Stepping Together Workbook involved the directions being unclear, and being too repetitive. One parent stated, “It didn’t explain a lot as far as what exercises the child is supposed to do. I had to go back and read it a couple times to understand it.” Only one parent disliked the workbook whereas the other seven parents reported that they found it the least helpful aspect of Step One.

Sixteen parents (47.1 %) in Step One reported that they liked the treatment being parent-led. There were five parents/caregivers (14.7 %) who disliked/found it least helpful. Two of these parents/caregivers were non-early responders and three early responders. Parents/caregivers in Step One reported liking and finding helpful the involvement they had in the treatment and also that they received therapist assistance during the treatment. For example, one parent/caregiver expressed the following about liking the involvement, “It challenges you as a parent to get involved in the kid’s feelings in the situation.” Another parent/caregiver stated, “You being that voice for them, you know, and you being there for them and actually have a few sessions with the therapist it shows that they’re there for you but you’re the one who is actually helping the child and that’s something that’s very well done.” Similarly, another parent commented the following regarding involvement, “Having a parent involved….I understand that my child needed treatment but the thought of him being somewhere privately without being involved in that and not knowing where to go as soon as we left the building with anything just frightened me not being involved. So being involved was unbelievable.” Two parents in Step One reported disliking/finding least helpful regarding the treatment being parent-led due to them wanting more therapist assistance during the treatment. Seven parents (20.6 %) reported liking/finding helpful the phone support that they received from the therapist.

Treatment Components

Twenty parents (58.8 %) in Step One and nine (50 %) in TF-CBT reported that what they liked/found helpful regarding their treatment was the relaxation. Parents in both conditions liked/found helpful the progressive muscle relaxation and diaphragmatic breathing techniques. For example, when asked what was the most helpful, a parent in Step One stated, “Teaching him how, when he’s upset, to get through it. Like the breathing and the arm exercises to help him…” Similarly a parent in TF-CBT commented, “[therapist] did a couple relaxation exercises with him and that was super helpful. He loves the balloon [diaphragmatic breathing]….”

Seventeen parents (50 %) in Step One reported liking/finding helpful the parent–child meetings while three parents in TF-CBT (16.7 %) reported liking/finding helpful the conjoint sessions. Specifically, parents in Step One liked/found helpful the time together and one on one time they spent with their children. One parent in Step One reported the following regarding one on one time, “The one-on-one that I got with him, instead of taking him to a counselor and not being a part of it because there’s a lot that I wouldn’t have learned about what happened with my son. He would have talked to a counselor and I would have never known, I would have never gotten to look in on that and know that part of his life.” No parents in TF-CBT reported these subthemes of time together and one-on-one time. Another subtheme expressed by parents in Step One was that they felt like the parent–child meetings opened the communication and enhanced the connection between the parent and child. One parent in Step One reported the following regarding enhanced connection: “I like how they allow the parent to really connect with the child, which made us closer. I didn’t think we could get any closer, but we did.” Parents in TF-CBT reported finding helpful the open communication and enhanced connection regarding the conjoint sessions as well as liking their involvement in the sessions. For example “That it [conjoint session] was more parents involved and interactive. I was incorporated more into the sessions and into their activities.”

Eleven parents (32.3 %) in Step One and ten (55.6 %) in TF-CBT reported that they liked/found helpful the parenting skills component of their treatment. Parents in both conditions endorsed liking/finding helpful the behavior plan and learning how to help their child, but only parents in TF-CBT reported receiving positive parenting suggestions as something they liked/found helpful. A parent in Step One stated the following regarding liking learning how to help their child, “I felt enlightened and empowered. I love that it had a very specific way to work through the issues that all seem to minimize the problems and symptoms and fears.” Similarly a parent in TF-CBT stated, “I was completely lost when I came here and didn’t have any hope and didn’t know what to do for my daughter. And now I’ve learned tools and skills to be able to cope with the issues.” Only one parent from each condition reported parenting skills as being least helpful. One Step One parent reported that the specific skill in question, the behavior plan, was against her parenting beliefs as she did not think she needed to reward her child for listening, and the other parent receiving TF-CBT reported that time-in time-out was least helpful because it did not work for her child.

Fourteen parents (41.2 %) in Step One and eight (44.4 %) in TF-CBT reported that what they liked/found helpful was the trauma narrative. Parents in both conditions liked/found helpful the child sharing the trauma narrative with the parent and the child telling his/her story. One parent in Step One who reported liking the sharing of the narrative stated, “I think it was good for her, it helped her to talk about the event more openly and freely and without shame and fear.” Another parent that expressed liking the trauma narrative stated, “The closeness that I have with my daughter while she discusses the things that have hurt her and we have developed a nice relationship of trust over the past couple weeks. I like the fact that she looks to me for answers on how to get through some of this stuff.”

One of the parents in TF-CBT who stated that the child telling his/her story was most helpful said, “I think that was really a closure for her. And then for me that is too, to know she understands what happened.” Another parent in TF-CBT who found the child telling his/her story as most helpful said, “And my daughter seems to be enjoying the storybook thing they’re working on. I don’t know too much yet, but they’re putting into story, picture, and words her trauma story basically. The story of what happened to her and how she can communicate that. She seems to actually want to work on it, so that’s different. I didn’t expect that.” One Step One parent reported liking exposures. She stated, “I did see him get a little anxious, but then he was able to calm himself down, which I thought was pretty amazing. I didn’t think little kids could do that.” Therapists used in vivo exposures in three cases, as needed, while providing TF-CBT treatment, but no TF-CBT parents commented on this component.

Fourteen parents (41.2 %) in Step One and seven (38.9 %) in TF-CBT reported liking/finding helpful the affect expression and modulation component. One parent in Step One who expressed liking the expression of feelings stated “I think it made her realize that you don’t have to keep it in. That you can talk about it or get it out in some way.” Parents in both conditions liked/found helpful the child expressing his/her feelings as well as learning to manage difficult affective states. One of the parents in TF-CBT that found this component helpful stated, “Making him aware of his feelings so he can acknowledge them and then express them. He knows all these new feelings now….” One Step One parent reported disliking “diving into the feelings” because the parent was unsure if doing so would result in the child reaching his “breaking point.” In terms of the cognitive coping component, six parents (17.6 %) in Step One and two (11.1 %) in TF-CBT reported liking/finding helpful the cognitive coping component. Parents in both conditions liked/found helpful exploring guilt and blame, but only parents in Step One endorsed exploring and correcting inaccurate or unhelpful cognitions as something they liked/found helpful.

Two parents (5.9 %) in Step One and four (22.2 %) in TF-CBT reported liking/finding helpful the safety component. Parents in both conditions liked/found helpful the enhancing safety element. Two parents (5.9 %) in Step One and three (16.7 %) in TF-CBT reported liking/finding helpful psychoeducation. One of the parents in Step One stated, “It helped point out my own feelings in regards to the trauma. The information about trauma in the ‘Just for You’ section helped with that.” Similarly, one TF-CBT parent stated, “I liked the process that she went through identifying what abuse was….” Three parents (16.7 %) in TF-CBT reported liking/finding helpful the homework, where parents/caregivers were asked to practice strategies suggested by the therapist. This component was part of the TF-CBT treatment.

General Aspects of Treatment

Eighteen parents (52.9 %) in Step One and 16 parents (88.9 %) in TF-CBT reported liking/finding helpful their therapist. Parents in both conditions liked/found helpful that they had a good connection with the therapist as well as their conversations and sessions with the therapist. When asked what they liked about the program, a parent in Step One stated, “The sessions when we went in-office and talked to her to make sure that we were on the right page and we were doing what we were supposed to.” One parent in TF-CBT noted the following regarding the sessions with the therapist, “Being able to go there and talk to somebody else. Having an open ear is good for her. Because some things you don’t want to tell your parents and a lot of new things are coming out. I think her being there is good.” Additionally, one parent from Step One reported that he/she disliked the sessions with the therapist, but only because he/she wanted to spend more time with the therapist.

Ten parents (29.4 %) in Step One and ten parents (55.6 %) in TF-CBT reported liking/finding helpful the content/structure of their treatment program, whereas five parents (14.7 %) in Step One and four parents (22.2 %) in TF-CBT disliked/found it least helpful. Regarding finding the structure of Step One helpful, one parent stated, “…the fact that it was structured and I didn’t really have to search for something to do. It was already established and so it made it easier for me.” Similarly, one parent in TF-CBT stated, “I like that it’s really focused and there’s pretty solid objectives and goals and she’s working through those things as it was outlined.” Reasons that Step One parents gave for disliking/finding least helpful the structure/content included wanting a stronger focus on behavior, being time consuming, wanting only one parent–child meeting per week, the book format not working due to child not listening, and the types of trauma covered being too specific and, at times, irrelevant. Furthermore, parents in TF-CBT disliked/found it least helpful due to wanting other family members to be involved, wanting more treatment, the program being too long, and two parents wanting longer sessions due to not being able to complete all content.

Nine parents (26.5 %) in Step One and three (16.7 %) in TF-CBT reported having difficulties implementing their treatment program. Parents in both conditions reported difficulty with parent tasks, difficulty following through with office appointments, and increased parental distress due to child distress. In regards to parent’s distress at their child’s distress, a parent in Step One commented, “It’s uncomfortable to have to have your child go through some of those processes. And it was uncomfortable for me, and it….but in the long run it helped me.” Similarly, a parent in TF-CBT commented, “I didn’t like seeing him distressed. I feel like at some points in the counseling he just reacted with distress and it was hard to watch.” Parents in both conditions expressed that they liked and felt comfortable in the program and that progress was made at the time of the assessment. Only one parent in Step One did not find that progress had been made because she did not see an improvement in her child’s behavior.

Suggestions

The main suggestion for SC-TF-CBT was regarding the Stepping Together Workbook. Eleven parents (32.4 %) provided suggestions for improving the workbook such as indicating better clarification of instruction (four parents) and more developmentally appropriate specifically for 3 year olds. Two parents indicated less repetition would be helpful and one of these parents also suggested including more of a variety of ways to express the trauma. There were two main suggestions regarding TF-CBT provided by four parents (22.2 %): feedback and longer or more intensive treatment. Two parents indicated that they wanted more feedback such as a having another professional observe or have the parent keep a weekly journal about the child for review by the therapist. Two parents wanted longer treatment and one parent wanted more intensive services such as home and school visits. Similar to SC-TF-CBT one parent wanted more of a variety in how the child expressed the trauma.

Exploratory Analyses

Results of the three exploratory analyses are as follows. (1) Exploratory analyses of themes about Step One at mid-treatment between Step One early responders (n = 22) and non-early responders (n = 10 plus 2 drop outs) were conducted; however, no major differences in themes between the two groups emerged. (2) We explored themes of parents who completed Step Two to their experiences of Step One (i.e., the same parent who experienced both therapist-led versus parent-led). Thematic analysis revealed two major differences in parents’ perceptions of Step One versus Step Two. First, parents favored the therapist during Step Two much more (100 %) than during Step One (50 %, 3 of 6), likely because Step Two provides weekly therapist-led treatment, whereas the therapist provided minimal assistance in Step One where the child did not respond. Second, parents also favored the trauma narrative in Step Two (50 %; 3 of 6) more than the trauma narrative in Step One (16.7 %, 1 of 6). (3) Examining the transcripts of the two parent–child dyads who dropped out of Step One did not reveal any codes that were not already endorsed by Step One completers.

Discussion

Overall, whether the parent or therapist led treatment, both treatments were acceptable to parents. Similarities expressed by parents, whether they participated in parent-led or therapist-led treatment included relaxation skills, affect modulation and expression skills, and trauma narrative. Also, the role and relationship with the therapist was important for both treatments. Parenting skills was also endorsed as a component that parents/caregivers liked and found helpful in both treatments, but a greater percentage of parents/caregivers in TF-CBT reported positive perceptions of this theme. Most parents who participated in Step One indicated that they liked and/or found helpful one of the components or aspects of it being parent-led which include the Stepping Together Workbook, parent–child meetings, and specifically that it was parent-led. However, there were some parents who did not like or find helpful the parent-led component due to wanting more therapist assistance. It is unclear if these parents would have preferred therapist-led treatment or if they wanted to lead the child’s treatment but wanted more assistance and contact with the therapist.

While the percentages of parents who endorsed liking/finding helpful the relaxation skills and affect modulation and expression skills were very similar across conditions, these two components, along with parent–child meetings/conjoint sessions and cognitive coping, had a higher percentage of parents reporting them as liked or helpful in Step One than TF-CBT. Relaxation may have been positively endorsed slightly more in Step One as children were taught three specific relaxation skills (e.g., deep breathing, muscle relaxation, and guided imagery of a happy place) where they practiced these skills in ten meetings, whereas in TF-CBT the relaxation component is taught and is a main treatment component, but it is not always systematically practiced each session. The slightly higher percentage of positive indications for affect expression and modulation in Step One versus TF-CBT may be due to the systematic nature of teaching children to rate how much they feel scared throughout the exposures, although TF-CBT also addresses affect expression and modulation as a main treatment component which is often used throughout treatment. The higher percentage of positive endorsement of the parent–child meetings in Step One than conjoint sessions in TF-CBT may be because there are 11 parent–child meetings in Step One, whereas typically only 2–3 conjoint sessions were held in TF-CBT. Cognitive coping may have been reported more frequently as being liked/helpful in Step One than TF-CBT because in the second therapist meeting the child is directly asked about being mad at others or themselves about what happened. Also, the in vivo exposures that are conducted during five parent–child meetings can serve as a way to revise cognitive distortions by learning that feared outcomes do not occur.

A greater percentage of parents in TF-CBT reported liking and/or finding helpful the parenting skills component and the therapist. On balance, parents in TF-CBT spent more time with the therapist and likely more time reviewing parenting skills with the therapist than did parents/caregivers in Step One. A recent study found that therapeutic alliance was a significant predictor of child outcome for TF-CBT but not for nonspecific psychotherapy (Ormhaug et al. 2014). It would be interesting to study the role of therapeutic alliance in parent-led treatment versus therapist-led treatment, and to explore if there are other differentiating mechanisms of change between the two service delivery approaches.

The vast majority of parents in both treatments found that having their child tell and share his/her story with his/her parent was a helpful part of treatment, although there was a slightly higher percentage of parents in TF-CBT suggesting liking and finding helpful the trauma narrative than in Step One. A major component of trauma-focused treatment is the trauma narrative (Deblinger et al. 2011), which was included in both parent-led and therapist-led treatment, although the actual telling of the story to the parent is conducted in only one session of Step One but occurs in 2–3 conjoint sessions in TF-CBT. Parents shared that they gained more knowledge about the trauma and that the completion of the trauma narrative provided a form of closure for them and their children. Approximately two-thirds of the youth in the Dittmann and Jensen (2014) study reported that the trauma narrative was very difficult to talk about, and while the younger children in this study were not asked about their experiences of the trauma narrative, it is noteworthy that none of the parents reported disliking and finding least helpful the trauma narrative. This difference may of course be due to the fact that the children were the ones who were having to tell their story and were experiencing PTSS, rather than the parents. Nonetheless, while there is some evidence that therapists may be reluctant to work on the trauma narrative with the child (Allen and Johnson 2012) and to conduct trauma-focused exposures (Sprang et al. 2008), none of the parents expressed disliking or finding least helpful these components. Despite exposures being an important component of Step One with six exposures (i.e., Next Steps), only one parent reported liking the exposures, but none of the parents reported disliking this component or finding it least helpful. Parents may have seen exposures as another activity completed as part of their parent–child meetings, especially since they were called Next Steps, indicating another task to be accomplished to help their children. It is also possible that parents may not have specifically identified Next Steps when interviewed, but may have included this as part of their overall comments regarding the parent–child meetings.

Parents in TF-CBT reported liking or finding helpful safety skills and psychoeducation more frequently than parents in Step One. Both treatments specifically address safety skills with the child and the parent, but it is possible that since therapists in TF-CBT have more time with the parents they most likely spent more time discussing safety with the parent. Similarly, both treatments address psychoeducation, usually in at least one designated session and often throughout treatment. However, given the limited time with the parent in Step One, the therapist provides psychoeducation in the first meeting and then refers the parent to the “Just for You” section in the workbook and the private website to learn more about the effects of trauma on young children or other information about trauma, thus limiting the amount of time the parent and therapist engage in conversation about psychoeducational topics.

A larger proportion of parents in TF-CBT reported liking and/or finding helpful the content and/or structure of the therapy compared to parents/caregivers in Step One, although both groups expressed some aspects that they did not like and/or found least helpful regarding the content and/or structure (more in TF-CBT, 22 %, than in Step One, 14.7 %). It is difficult without further research to know if these concerns were specific to these parents or are more generalizable problems which need to be addressed within the treatments. Parents in both conditions reported implementation difficulty, although parent/caregivers in Step One (26.5 %) expressed more difficulty than TF-CBT (16.7 %). Again, further research will need to examine if these difficulties are specific to the treatment provided or more general to all types of treatments. For example, difficulty following through with appointments may be related to common treatment barriers associated with difficulty attending weekly in-office appointments (Bringewatt and Gershoff 2010) or it may be related to the treatment such that the parent did not attend the appointment due to not completing the Stepping Together Workbook in Step One or the parent did not attend because it was difficult to attend a weekly appointment for 3 months. Nonetheless, future development of Stepped Care TF-CBT will need to focus on addressing implementation difficulties that can minimize treatment barriers. This study provides evidence that some parents like and find helpful leading the child’s treatment and meeting with the child to complete trauma-focused activities. Many parents specifically reported liking that they were a significant part of their child’s treatment and that they liked that a therapist was also able to assist them in the process. Some parents reported disliking or finding least helpful that the treatment was parent-led due to their own uncertainty about doing the parent–child meetings and wanting more therapist guidance through the process. It seems that some parents may need more assistance than others as well as more clarification when leading Step One treatment. Further exploration of identifying which parents may need more clarification and more guidance may be needed, or it may be beneficial to build more parent support into the model.

The majority of parents (61.8 %) in Step One reported liking and/or finding helpful the Stepping Together Workbook, but some reported disliking or finding it not as helpful as the other components. Some parents reported that the workbook included unclear directions, and some parts were too repetitive. The repetition was due to the same instructions being used for the drawing, imaginal exposure and Next Steps. In some cases, children were exposed to the same trauma trigger but with gradual frequency and intensity. For example, a first exposure might involve driving by a school bus which served as a reminder about the trauma. The second exposure might have involved walking toward a school bus with the last exposure involving the child and parent getting on the school bus. Some parents may not have understood the importance of the repetition. Therefore, the workbook and therapist will need to provide a more in-depth rational when repetition to exposure reminders is used. Some parents suggested that the workbook be geared more toward 3 year olds. It will be important to continue to refine the book to make sure it is developmentally sensitive to very young children.

A major benefit noted by parents leading treatment was that the parent and child were able to spend quality time together and it helped in the opening up of communication between them. No parents in either treatment reported wanting to be less involved in their child’s treatment. Future studies should explore how the strengthened relationship and enhanced communication may improve outcomes from the child. Due to the small sample, we were not able to detect differential patterns between parents with varying characteristics. Future research may explore if there are sociocultural, gender, or educational level differences or differences based on parent symptomology (i.e., PTSD, depression) in parents’ perceptions of leading the child’s trauma-focused treatment.

There are several limitations of the current study that are important to acknowledge. First, inherent in qualitative studies, findings may not be generalized. Future studies with various populations and larger samples are needed and will allow for examination of differential perceptions and preferences based on parent and child characteristics. Second, the voices of the young children in terms of their perceptions about their parent leading treatment was not included, and is an important direction for future research. Third, while the interview format allowed for varied responses about likes and dislikes and things that parents found helpful and least helpful, more specific questions about the components may have elicited different results. Future studies should include questions about the components. Since the questions about what parents liked was followed by what they found most helpful and the question about what they disliked was followed by what they found least helpful, some parents reported the same response for the positive and negative questions which may have led to biases in response. Fourth, there were some instances where feedback was not provided. One parent was excluded from this study due to not participating in any interviews and three parents missed interviews at one time point. However, the three parents who missed interviews did participate in at least one of the two interviews.

The current study is the first to explore parents’ perceptions of leading a trauma-focused treatment for children. Results suggest that a parent-led therapist-assisted treatment may be as acceptable as therapist-led treatment to many parents, and that parents’ working directly with the child to help the child process the traumatic event is feasible. The SC-TF-CBT model that consists of a first-line parent-led treatment with minimal therapist support with the second step reserved for children needing more intensive therapist-led treatment may serve as a model for other childhood disorders.

Acknowledgments

The project was supported by National Institute of Mental Health award R34MH092373 to Dr. Salloum. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health or the National Institutes of Health. The authors would like to thank the Crisis Center of Tampa Bay, where the study treatment was provided, particularly Melissa Thompson, MSW, Karen Allen, RMHCI, Angela Claudio Torres, LMHC, Awneet Chandhok, RMFTI, Tia Burr, and Kyra Snyder, Debbie Lyublanovits, LMHC, Vicki Hummer, LCSW, Tom Marco, Sunny Hall, and David Braughton, President & CEO. The contributions of Michael Scheeringa, M.D. at Tulane University in New Orleans, LA, Judy Cohen, M.D. at Center for Traumatic Stress in Children and Adolescents, Allegheny General Hospital in Pittsburgh, PA, David Tolin, Ph.D. at Anxiety Disorders Clinic, The Institute of Living in Harford, CT, Wei Wang, Ph.D. and John Robst, Ph.D., and Brittany Kugler, M. A. at the University of South Florida in Tampa, FL are gratefully acknowledged.

References

- Allen B, Johnson JC. Utilization and implementation of trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy for the treatment of maltreated children. Child Maltreatment. 2012;17(1):80–85. doi: 10.1177/1077559511418220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker-Ericzen MJ, Jenkins MM, Haine-Schlagel R. Therapist, parent, and youth perspectives of treatment barriers to family-focused community outpatient mental health services. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2013;22(6):854–868. doi: 10.1007/s10826-012-9644-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briere J, Johnson K, Bissada A, Damon L, Crouch J, Gil E, Ernst V. The Trauma Symptom Checklist for Young Children (TSCYC): Reliability and association with abuse exposure in a multi-site study. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2001;25(8):1001–1014. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(01)00253-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bringewatt EH, Gershoff ET. Falling through the cracks: Gaps and barriers in the mental health system for America’s disadvantaged children. Children and Youth Services Review. 2010;32(10):1291–1299. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cary CE, McMillen J. The data behind the dissemination: A systematic review of trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for use with children and youth. Children and Youth Services Review. 2012;34(4):748–757. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JA, Deblinger E, Mannarino AP, Steer RA. A multisite, randomized controlled trial for children with sexual abuse-related PTSD symptoms. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43(4):393–402. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200404000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Mannarino AP. Disseminating and implementing trauma-focused CBT in community settings. Trauma, Violence and Abuse. 2008;9(4):214–226. doi: 10.1177/1524838008324336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JA, Mannarino AP, Deblinger E. Treating trauma and traumatic grief in children and adolescents. New York. NY: Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- de Arellano MA, Lyman DR, Jobe-Shields L, George P, Dougherty RH, Daniels AS, Delphin-Rittmon ME. Trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy for children and adolescents: Assessing the evidence. Psychiatric Services. 2014;65(5):591–602. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deblinger E, Lippmann J, Steer R. Sexually abused children suffering posttraumatic stress symptoms: Initial treatment outcome findings. Child Maltreatment. 1996;1:310–321. [Google Scholar]

- Deblinger E, Mannarino AP, Cohen JA, Runyon MK, Steer RA. Trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for children: Impact of the trauma narrative and treatment length. Depression and Anxiety. 2011;28(1):67–75. doi: 10.1002/da.20744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deblinger E, Stauffer LB, Steer RA. Comparative efficacies of supportive and cognitive behavioral group therapies for young children who have been sexually abused and their nonoffending mothers. Child Maltreatment. 2001;6(4):332–343. doi: 10.1177/1077559501006004006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittmann I, Jensen TK. Giving a voice to traumatized youth—Experiences with Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2014;38(7):1221–1230. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert L, Amaya-Jackson L, Markiewicz JM, Kisiel C, Fairbank JA. Use of the breakthrough series collaborative to support broad and sustained use of evidence-based trauma treatment for children in community practice settings. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2012;39(3):187–199. doi: 10.1007/s10488-011-0347-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy W. ECDEU assessment manual for psychopharmacology. Washington, DC: US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen TK, Holt T, Ormhaug SM, Egeland K, Granly L, Hoaas LC, Wentzel-Larsen T. A randomized effectiveness study comparing trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy with therapy as usual for youth. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2014;43(3):356–369. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.822307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King NJ, Tonge BJ, Mullen P, Myerson N, Heyne D, Rollings S, et al. Treating sexually abused children with posttraumatic stress symptoms: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:1347–1355. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200011000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moustakas C. Phenomenology and the social sciences. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Murray LK, Familiar I, Skavenski S, Jere E, Cohen J, Imasiku M, Bolton P. An evaluation of trauma focused cognitive behavioral therapy for children in Zambia. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ormhaug SM, Jensen TK, Wentzel-Larsen T, Shirk SR. The therapeutic alliance in treatment of traumatized youths: Relation to outcome in a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2014;82:52–64. doi: 10.1037/a0033884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salloum A, Robst J, Scheeringa MS, Cohen JA, Wang W, Murphy TK, Storch EA. Step one within stepped care trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for young children: A pilot study. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 2014;45:65–77. doi: 10.1007/s10578-013-0378-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salloum A, Scheering MS, Cohen JA, Amaya-Jackson L. Stepping together: Parent–child workbook for children (ages 3 to 7) after trauma, Version 1.2: Unpublished book. 2009 asalloum@usf.edu. [Google Scholar]

- Salloum A, Scheeringa MS, Cohen JA, Storch EA. Development of stepped care trauma focused cognitive-behavioral therapy for young children. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2013;21:97–108. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2013.1007.1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salloum A, Storch EA. Parent-led, therapist-assisted, first-line treatment for young children after trauma: A case study. Child Maltreatment. 2011;16(3):227–232. doi: 10.1177/1077559511415099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salloum A, Wang W, Robst J, Murphy T, Scheeringa MS, Cohen JA, Storch EA. Stepped care versus standard trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for young children. 2015 doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12471. Submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheeringa MS, Amaya-Jackson L, Cohen JA. Preschool PTSD treatment manual, version 1.6. New Orleans, LA: Tulane Institute of Infant & Early Childhood Mental Health; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Scheeringa MS, Haslett N. The reliability and criterion validity of the diagnostic infant and preschool assessment: A new diagnostic instrument for young children. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 2010;41(3):299–312. doi: 10.1007/s10578-009-0169-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheeringa MS, Salloum A, Arnberger RA, Weems CF, Amaya-Jackson L, Cohen JA. Feasibility and effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder in preschool children: two case reports. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2007;20(4):631–636. doi: 10.1002/jts.20232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigel BA, Benton AH, Lynch CE, Kramer TL. Characteristics of 17 statewide initiatives to disseminate trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy (TF-CBT) Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2013;5(4):323–333. doi: 10.1037/a0029095. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sprang G, Craig C, Clark J. Factors impacting trauma treatment practice patterns: The convergence/divergence of science and practice. Anxiety Disorders. 2008;22:162–174. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurston IB, Phares V. Mental health service utilization among African American and Caucasian mothers and fathers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76(6):1058–1067. doi: 10.1037/a0014007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]