Abstract

The advantages of using bacterial systems to study the mechanism and function of cytochrome bc1 complexes do not extend readily to their structural investigations. High quality crystals of bacterial complexes have been difficult to obtain despite the enzymes' smaller sizes and simpler subunit compositions compared to their mitochondrial counterparts. In the course of the structure determination of the bc1 complex from R. sphaeroides, we observed that the growth of only low quality crystals correlated with low activity and stability of the purified complex, which was mitigated in part by introducing a double mutations to the enzyme. The S287R(cyt b)/V135S(ISP) mutant shows 40% increase in electron transfer activity and displays a 4.3°C increase in thermal stability over wild-type enzyme. The amino acid histidine was found important in maintaining structural integrity of the bacterial complex, while the respiratory inhibitors such as stigmatellin are required for immobilization of the iron-sulfur protein extrinsic domain. Crystal quality of the R. sphaeroides bc1 complex can be improved further by the presence of strontium ions yielding crystals that diffracted X-rays to better than 2.3 Å resolution. The improved crystal quality can be understood in terms of participation of strontium ions in molecular packing arrangement in crystal.

Introduction

The cytochrome bc1 complex (cyt bc1 or bc1), also known as ubiquinol cytochrome c oxidoreductase, is a multi-subunit integral membrane protein that constitutes an essential component of the cellular respiratory chain; It catalyzes electron transfer from ubiquinol to cyt c coupled with proton translocation across the membrane [1]. The cross-membrane electrochemical gradient is used as an energy source to generate ATP by ATP synthase. Subunit compositions of bc1 complexes vary depending on organisms ranging from three subunits in P. denitrificans and R. capsulatus [2, 3] to as many as eleven subunits, as in bovine mitochondria [4]. Three redox subunits are essential and are found in all species; they are cyt b housing hemes bL and bH, cyt c1 containing a heme c and the Iron sulfur protein (ISP) featuring a 2Fe-2S cluster [5, 6]. All additional subunits, referred to as supernumerary subunits, are believed to contribute to the increased stability of the protein [7, 8]. Despite its size (500 kDa for the dimer) and complexity (11 different subunits in a monomer), crystal structures for the bovine mitochondrial cyt bc1 complex (Bos taurus bc1, Btbc1) were determined first [9-11]. The bc1 complex isolated from R. sphaeroides (Rsbc1), on the other hand, has been defying crystallization efforts until very recently [12], even though it is smaller in size (250 kDa per dimer) due to its much simpler composition having only one supermumerary subunit: subunit IV [8]. The simpler subunit composition, amenable to genetic manipulations, and easy to express and purify in large quantity make the Rsbc1 an excellent model of the mitochondrial complex and an ideal system for investigating into the mechanism of bc1 function. Indeed, most of the structural information obtained from the mitochondrial enzyme has been validated via molecular genetic manipulations of the bacterial enzyme. Although the structures of the bacterial and mitochondrial complexes were expected to be very similar, an experimental structure of the bacterial bc1 was highly desirable due to sequence variations and numerous insertions and deletions in the bacterial sequences.

Despite its simple composition and small size, the structure determination of Rsbc1 had been hampered by poor crystal qualities, a problem also apparent in the structure from R. capsulatus [13]. As it is common in membrane protein crystallization, a number of factors could affect the diffraction quality of Rsbc1 crystals. Firstly, the considerably larger proportion of hydrophobic surface compared to mitochondrial complexes limits the amount of hydrophilic interactions that are essential for crystal contacts, pointing to a more challenging crystallization case. Secondly, compared to mitochondrial enzymes, purified Rsbc1 has significantly lower electron transfer (ET) activity, which are correlated to complex stability and ultimately to crystal quality. Furthermore, structures of the Btbc1 revealed a highly mobile iron-sulfur protein extrinsic domain (ISP-ED), whose rapid motion is required for function as demonstrated experimentally [14-16]. In this report, we demonstrate that by carefully monitoring Rsbc1 activity and structrual stability, complex monodispersity, and conformational uniformity in solution, we found conditions that led to the reproducible crystallization of this membrane protein complex and to well-diffracting crystals up to 2.35 Å resolution.

The requirement of histidine for complex integrity and monodispersity

Recombinant wild-type Rsbc1 can be over-expressed in and purified from the R. sphaeroides strain BC17 bearing a plasmid pRKDfbcFBC6HQ; the Rsbc1 thus obtained has a his-tag at the C-terminus of the cyt c1 subunit for easy purification by affinity chromatography [17]. Initially, during purification, the elution profiles from a Ni-NTA column showed a long trailing peak when the bound Rsbc1 was eluted with imidazole. This problem was solved when imidazole was replaced by the amino acid histidine in the elution buffer. In subsequent gel filtration experiments, it was found that in the absence of histidine, the protein complex has a dendency to fall apart, whereas 200 mM of histidine maintained the subunit integrity of the Rsbc1 in solution (Fig. 1). In an attempt to improve the quality of the resulting crystals, we tried to replace histidine in the crystallization buffer by pyrazole, tetrazole, histidinole, 4-bromo-imidazole and melamine but without success. Thus, in all subsequent purification steps and crystallization trials, the buffers contained 200 mM histidine.

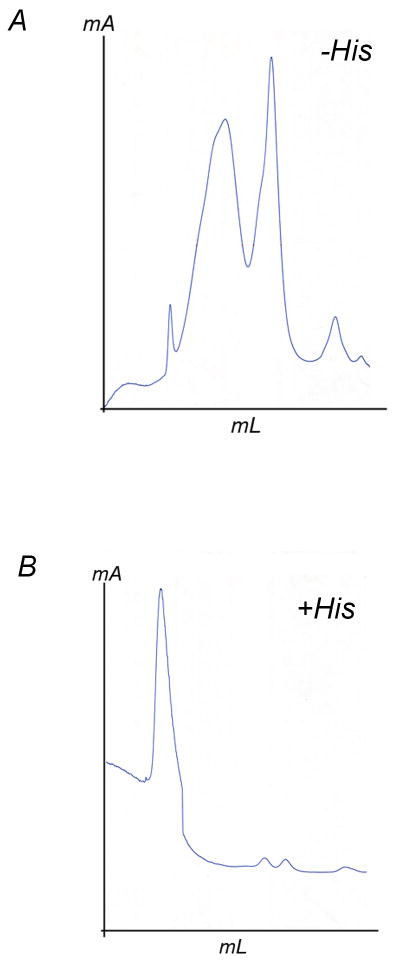

Figure 1. Requirement of histidine for the structural integrity of Rsbc1 complex.

(A) Gel-filtration chromatograph of purified Rsbc1 in the absence of histidine. The protein sample was run on a sephadex 200 column (GE Health Science) with a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min in a buffer containing 50 mM MOPS, pH 8.0, 0.5% β-OG, 0.12% SMC, 200 mM NaCl and 10% glycerol. (B) Gel-filtration chromatograph of purified Rsbc1 in the presence of 200 mM histidine. All other parameters are identifical to (A).

Achieving conformational uniformity using respiratory inhibitors

Structure solutions of cyt bc1 from bovine and chicken mitochondria revealed a highly mobile extrinsic domain for the ISP subunit (ISP-ED), which appeared in various positions in different crystal environments [9, 18, 19]. It was shown experimentally that movement of ISP-ED is required for the function of the bc1 complex [15, 16] and could be arrested by a certain type of respiratory inhibitor such as stigmatellin or UHDBT [10, 20]. While functionally essential, the free movement of ISP-ED is highly undesirable during crystallization efforts. Due to its particular effectiveness in arresting ISP-ED, stigmatellin has been often used and described to be essential in the crystallization of yeast mitochondrial bc1 [21] and R. capsulatus bc1 [13]. In our initial crystallization condition, the Rsbc1 protein proteins was solubilized in a solution containing 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 0.5 % β-OG, 200 mM NaCl, and 200 mM histidine, was pre-incubated with stigmatellin (five-fold molar excess), and was readily crystallized by adding 4% PEG3500.

A problem of anisotropic diffraction of Rsbc1 crystals

Despite early successes, all Rsbc1 crystals were fragile and produced only relatively weak and highly anisotropic diffraction images (Fig. 2A, Table 1). Fundamental difficulties in crystallizing membrane proteins have their roots in the fact that crystals need to grow from a mixture of protein-detergent-complex (PDC) and detergent micelles. For membrane proteins with a relatively large hydrophilic surface such as mitochondrial bc1, crystal contacts are often formed between polar residues, leading to Type-II crystals [22, 23]. In contrast, membrane proteins with small hydrophilic surfaces as exemplified by bacteriorhodopsin often pack together to form two-dimensional plane sheets, which stack in the 3rd dimension to form Type-I crystals [22, 23]. Based on the amount of hydrophobic surface, it is conceivable that Rsbc1 crystals would belong to Type-I, which would be consistent with the observation that the first Rsbc1 crystals were often hexagonal-shaped and showed better diffraction along the six-fold axis, suggesting conversely, a poor molecular packing within the plane sheets. To improve the quality of Rsbc1 crystals, molecular packing within a membrane plane-sheet as well as contacts between plane-sheets must be improved. It is conceivable that a more rigid protein would likely improve lateral packing of dimeric bc1 molecules in the membrane plane, and by modulating sizes of detergent micelles, two-dimensional plane-sheets in a type-I crystal might be better aligned, giving rise to better quality crystals.

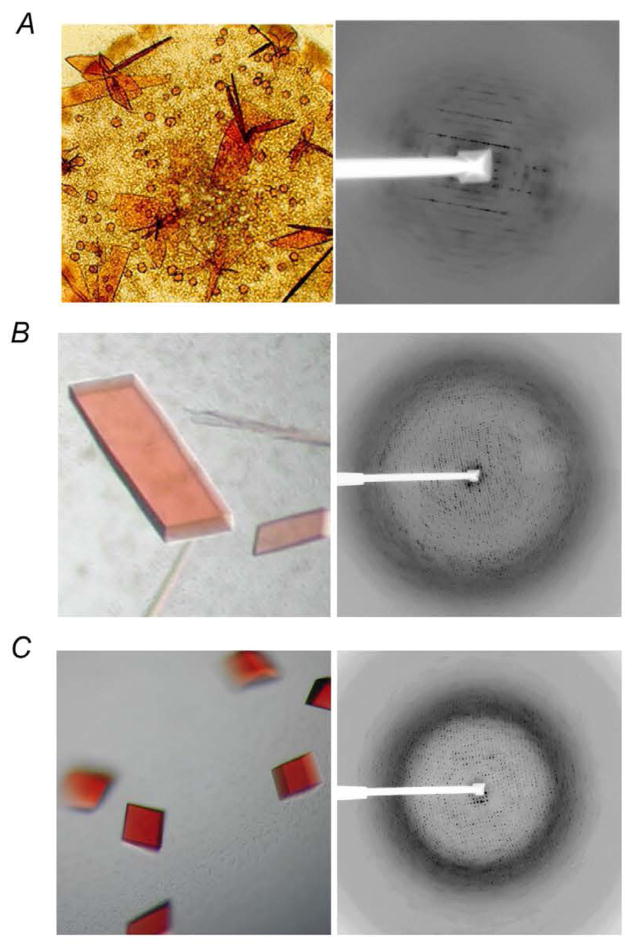

Figure 2. Crystals of R. Sphaeroides cytochrome bc1 complex and their diffraction images at various stages of crystallization efforts.

(A) Wild type Rsbc1 and its anisotropic, low-resolution diffraction pattern at early stage of bc1 crystallization. (B) Images of mutant Rsbc1 crystals and its diffraction. (C) Crystals of Rsbc1 mutant grown in the presence of strontium ion and its diffraction to 2.3 Å resolution.

Table 1. Improvement in Rsbc1 crystallization over time and properties of various Rsbc1 crystals1.

| Protein sample | Year | QN site inhibitor | Second detergent | Metal ion | No. dimer per AU | Resolution (Å) |

SG2 | Cell parameters a, b, c, α, β, γ (Å, °) |

PDB Code |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 2000 | None | None | None | - | 8 | P6 | - | - |

| Double mutant3 | 2004 | None | SMC | Sr2+ | 3 | 3.2 | C2 | 351.3, 147.1, 160.8, 90, 103.9, 90 | 2FYN4 |

| Double mutant | 2004 | UQ25 | SMC | Sr2+ | 3 | 2.8 | C2 | 353.4, 147.1, 182.3, 90, 104.5, 90 | - |

| ΔSub4-mutant | 2005 | Ant6 | SMC | Sr2+ | 2 | 3.0 | P1 | 128.9, 127.0, 127.9, 64.65, 87.71, 61.80 | - |

| Double mutant | 2005 | Ant | Cymal-6 | Sr2+ | 3 | 3.1 | C2 | 352.3, 147.4, 160.8, 90, 104.1, 90 | 2QJK |

| Double mutant | 2005 | UQ2 | SMC | Sr2+ | 3 | 2.35 | C2 | 352.2, 147.2, 161.5, 90, 104.2,90 | 2QJY |

| Wild type | 2006 | Ant | SMC | Sr2+ | 2 | 2.6 | P21 | 135.1, 146.5, 141.0, 90, 110.2, 90 | 2QJP |

All crystallization conditions include 3-5 fold molar excess of stigmatellin, which binds at the QP site.

Space group.

Rsbc1 contains two mutations: S287R in cyt b and V135S in ISP.

Coordinates that have been deposited.

Uquinone derivative with two isoprenoid repeats.

Antimycin A.

Engineering a highly active and stable Rsbc1 complex

Establishing and maintaining sample stability and conformational uniformity present considerable challenges in membrane protein crystallization. However, it has been known for some time that bacterial bc1 complexes have much lower ET activities and are less stable than their mitochondrial counterparts, presumably due to the lack of supernumerary subunits [7]. Since the crystallization process often involves a prolonged incubation period, a more stable and rigid protein may be useful to improve the crystallization behavior of Rsbc1. Similar approach has been reported in successful crystallization of homologous proteins from thermophilc organisms for their stabilities. The observed mobility of the ISP-ED and easy detachment of ISP subunit from the complex led us to search for more stable mutant proteins by introducing cross interactions between subunits based on mitochondrial bc1 structures [24]. One mutant was found bearing double mutations S287R in cyt b and V135S in ISP, which exhibited the expected enhancement in enzymatic activity and protein stability [12].

The R. sphaeroides strain harboring the mutant bc1 complex grows photosynthetically at a similar rate to that harboring the wild type enzyme. Interestingly, enzymatic activities in both isolated chromatophore membranes and in purified forms increased by 40%, as compared to the wild type protein (Table 2). The enhanced activeity was attributed to the increase in complex stability, which was demonstrated by monitoring enzyme activities of both mutant and wild type enzymes over a prolonged period of time at different temperatures (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, subsequent differential scanning calorimetry showed an increase of ΔTm = 4.3°C in the melting temperature for the mutant protein over the wild type enzyme (Fig. 3B).

Table 2. Summary of wild type and mutant characteristics.

| Enzymatic activity2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain | Mutation | Corresponding residue in bovine | Ps growth1 | Chroma-tophore | Purified protein | Protein Soret / UV ratio |

| Wt | - | - | +++ | 2.0 | 2.5 | 1.2 |

| Mutant | S287R (cyt b) V1335S (ISP) | N263 (cyt b) V145 (ISP) | +++ | 2.8 | 3.5 | 1.3 |

Ps Growth (+++) refers to the photosynthetic growth rate of wild type cells.

The enzymatic activity is expressed as μmol cyt c reduced/min/nmoles cyt b.

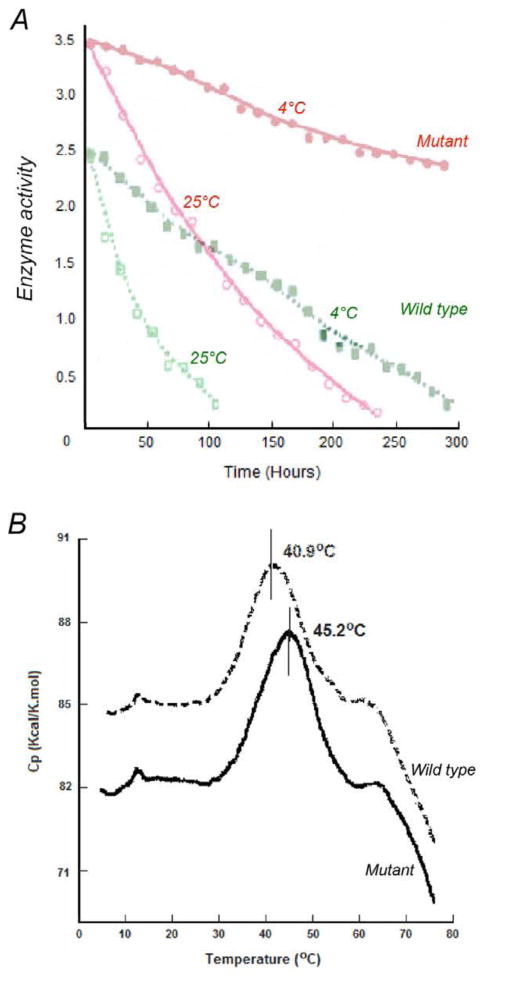

Figure 3. Stabilities of purified cyt bc1 complexes of wild type and mutant.

(A) The enzymatic activities of wild type and mutant Rsbc1 complexes were followed over 300 hours at 4°C and over 100 hours at 25°C, respectively. Within four days (100 hours) of incubation at 25°C, the wild type proteins become inactive whereas the SR mutant proteins still preserve about 50% of activity. Within 12 days (300 hours) of incubation at 4°C, the mutant proteins conserve 70% of activity as compared to nearly complete inactivation of the wild type protein. (B) Differential scanning calorimetric study of purified cyt bc1 complexes. The thermo-denaturation temperature of the wild type (dashed line) and mutant (solid line) cyt bc1 complex is 45.2°C and 40.9°C, respectively. Purified protein (0.55mL of 15μM cyt bc1 complex from wild type or mutant) was subjected to differential scanning calorimetry.

Crystallization of Rsbc1 mutant and cryo protection

The Rsbc1 mutant behaved significantly better even with the crystallization conditions used for the wild type enzymes. Crystals that diffracted X-rays to a much better resolution were routinely obtained, although anisotropy in diffraction patterns persisted. High-resolution diffractions were difficult to achieve in part due to the use of cryo-protection procedure for Rsbc1 crystals, which involved in step-wise soaking of cryo-protectants into crystals prior to X-ray data collection and inevitably damaged the diffraction quality of Rsbc1 crystals. Screening with lower molecular weight precipitants such as polyethylene glycols (PEGs) were conducted, which are themselves cryo-protectants, and Rsbc1 crystals were successfully obtained in PEG400. Crystals grew under these conditions were frozen readily with liquid propane at liquid nitrogen temperature and diffracted X-rays to 2.9 Å resolution (Fig 2B & Table 1).

Structure determination and crystal packing analysis

Crystals of mutant Rsbc1 in complex with stigmatellin frequently have the symmetry of the space group C2 and have large unit cell dimensions (Table 1). The structures of Rsbc1-inhibitor complexes were solved by molecular replacement (MR) method using a dimeric Rsbc1 model based largely on the structure of bovine bc1 with minor modifications. Surprisingly, only the three core subunits were present (Fig. 4A); apparently, subunit IV was lost upon crystal formation. This observation was confirmed by SDS-PAGE analysis of Rsbc1 crystals, which showed no band corresponding to subunit IV but it was however present in the mother liquor (Data not shown). Crystallization with purified three-subunit Rsbc1 (ΔSub4-Rsbc1) was also successful under conditions similar to four-subunit Rsbc1 (Table 1). The assembly of the three-subunit Rsbc1 resembles closely that of the corresponding subunits in bovine mitochondrial bc1.

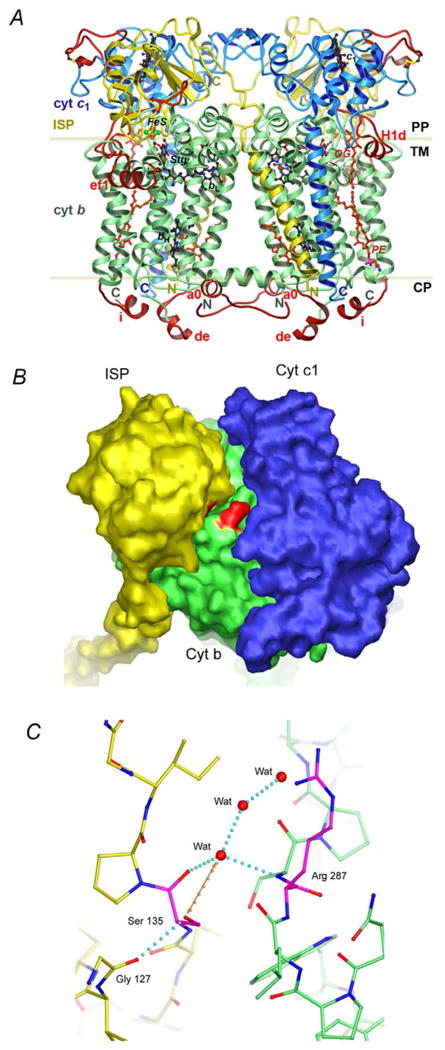

Figure 4. Structure of the wild type and mutant three-subunit Rsbc1.

(A) Structure of the dimeric Rsbc1 in ribbon representation with the bound QP site inhibitor stigmatellin and QN site substrate ubiquinone. Color assignment is the following: green, cyt b; blue, cyt c1 and yellow, ISP. The insertions and extensions that distinguish Rsbc1 from its mitochondrial counterpart are colored in red. Prosthetic groups and stigmatellin are shown as the ball-and-stick models with carbon atoms colored in black, oxygen red, nitrogen blue, sulfur green and iron brown. Modeled lipid and detergent molecules are shown as the ball-and-stick models in red. The boundary of lipid bilayer is indicated with the two parallel lines. The trans-membrane domain (TM), the periplasmic (PP) and cytoplasmic (CP) space are also labeled. (B) Surface diagram of the three-subunit Rsbc1 shows the cyt b subunit in green, cyt c1 in blue and ISP in yellow. The two mutations are highlighted in red located at the interface. (C) Stick model showing interactions at the mutation site. Carbon atoms from residues in the ISP subunit are yellow and those from the cyt b subunit are green, whereas those for the two mutations are shown in magenta. Oxygen atoms are red and nitrogen blue. Water molecules are given as red balls.

Although the expected interaction between the side chains of Arg287 and Ser135 of the mutant Rsbc1 is not observed, several observations from the mutant structure may explain the enhancement in stability of the mutant enzyme. The introduction of two mutations, S287R in cyt b and V135S in ISP, at the interface considerably alters the surface property of the enzyme in this region, redering a more hydrophilic interface than that for the wild type enzyme (Fig. 4B). As a result, ordered water molecules are localized at the interface (Fig. 4C). These solvent molecules clearly bridge hydrogen-bonding interactions between the two subunits, providing additional stability to the complex. Additionally, the hydroxyl group of Ser135 has a potential to form a hydrogen bond with the main chain amide nitrogen atom of Arg287, thus stablilizes the complex.

As expected, the mutant Rsbc1 crystals are Type-I membrane protein crystals. Three bc1 dimers occupy the crystallographic asymmetric unit (Fig. 5A). In the crystal, dimeric bc1 molecules are aligned side-by-side in a two-dimensional plane sheet. These sheets are then stacked on top of each other to form a three-dimensional crystal.

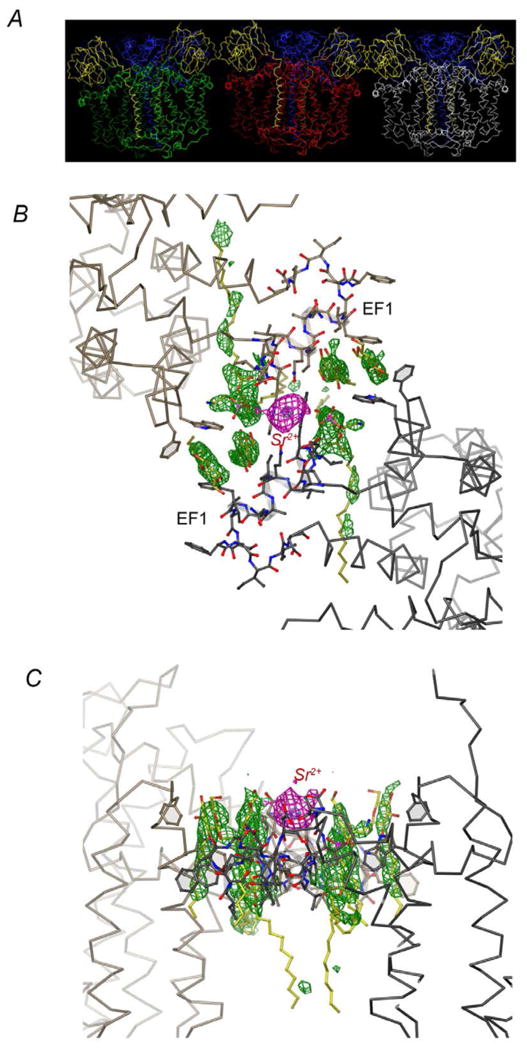

Figure 5. Packing interactions in Rsbc1 crystal.

(A) Packing of the three Rsbc1 dimers in the asymmetric unit in space group C2. The three independently determined dimers are shown with the three cyt b dimers in green, red, and white, respectively. The ISP subunits are yellow and cyt c subunits blue. (B) Interactions at the interface between dimers mediated by Sr2+. This is the view from periplasma looking down the cytoplasmic membrane. The two Rsbc1 dimers contact each other through the EF1 insertion, which is unique to photosynthetic bacteria. The anomalous electron density from the Sr2+ ion is given in magenta, whereas the difference density shown in green are likely from bound lipid molecules. (C) The same as (B) except viewed parallel with the membrane plane.

Overcoming anisotropic diffraction by using detergent mixtures and strontium ions as additive

We found that the directions of weak intensities in the anisotropic diffraction patterns of Rsbc1 crystals are invariably associated with the packing of Rsbc1 molecules in stacked two-dimensional plane sheet. To overcome the problem of anisotropic diffraction, we considered it paramount to identify conditions that would provide stronger, specific interaction between Rsbc1 molecules in the adjacent two-dimensional plane sheets. We focused on the optimization of two crystallization parameters that we deemed particularly important. First, as detergent micelles may be incorporated into protein crystals, their average size and shape represent adjustable parameters. Secondly, specific interactions between neighboring molecules could be established or strengthened by metal ions – a phenomenon that has been shown previously [25]. To optimize the first parameter, a detergent screen kit consisting of moret than 50 different detergents and small molecule amphiphiles at various concentrations was used for screening. The sugar based detergent sucrose mono carprate (SMC) yielded crystals with good morphology and improved diffraction quality. Next, a number of mono and multivalent metal ions was screened, which established strontium nitrate as a successful additive. In the presence of both SMC and Sr2+, the Rsbc1 mutant crystals diffracted X-rays to better than 2.3 Å resolution with a complete data set collected to 2.35 Å resolution (Fig. 2C, Table 1). Although it is difficult to visulize the shape and size of detergent micelles in crystals, metal irons can often be seen. In the crystal, a difference Fourier map revealed a large peak at the interface between two dimers (Fig. 5B &C). Serendipitously, the helical insertion EF1 helix (312-327) in cyt b found in photosynthetic bacteria promotes inter-dimer interactions supported by as of yet unidentified lipid components as well as by a strontium ion.

Crystallization of wild-type Rsbc1

The purified protein at a concentration of 15 mg/ml (in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.5, 0.5% β-OG, 5 mM NaN3, 200 mM NaCl, 200 mM histidine, and 10% glycerol, 0.12% SMC, and 10 mM Sr(NO3)2) is incubated with three to five fold molar excess of stigmatellin and mixed with PEG400 to a final concentration of 8% to 10%. The mixture was allowed to stand overnight at 4°C. A small amount of precipitate was removed by centrifugation and the clear supernatant was used for crystallization by vapor diffusion in sitting drops at 15°C. Small, red translucent crystals appear within four to six weeks. Notably, this condition established first for the crystallization of mutant R. sphaeroides cyt bc1 allowed us to produce wild-type Rsbc1 crystals that diffracted to 2.6 Å resolution with significantly reduced anisotropy. The wild-type enzyme crystallizes with two dimers per asymmetric unit (space group P21, Table 1). The structure of the wild-type complex (P21) was solved by MR using a refined dimeric polypeptide-only model of the mutant Rsbc1.

Abbreviations

- bc1

complex, ubiquinol-cytochrome c oxidoreductase

- bH

high potential cytochrome b heme

- bL

low potential cytochrome b heme

- Btbc1

Bos taurus bc1

- cyt

cytochrome

- DSC

differential scanning calorimetry

- ET

electron transfer

- ISP

Rieske iron-sulfur protein subunit

- ISP-ED

ISP extrinsic domain

- PDC

protein-detergent complex

- PEG

polyethylene glycol

- MR

molecular replacement

- [2Fe-2S]

Rieske iron-sulfur center. SMC, sucrose monocaprate

References

- 1.Trumpower BL, Gennis RB. Energy transduction by cytochrome complexes in mitochondrial and bacterial respiration: the enzymology of coupling electron transfer reactions to transmembrane proton translocation. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 1994;63:675–716. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.003331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang X, Trumpower BL. Purification of a three-subunit ubiquinol-cytochrome c oxidoreductase complex from Paracoccus denitrificans. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1986;261:12282–12289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robertson DE, Ding H, Chelminski PR, Slaughter C, Hsu J, Moomaw C, Tokito M, Daldal F, Dutton PL. Hydroubiquinone-cytochyrome c2 oxidoreductase from Rhodobacter capsulatus: definition of a minimal, functional isolated preparation. Biochemistry. 1993;9:1310–1317. doi: 10.1021/bi00056a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schagger H, Brandt U, Gencic S, von Jagow G. Ubiquinol-cytochrome-c reductase from human and bovine mitochondria. Methods Enzymol. 1995;260:82–96. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)60132-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trumpower BL The protonmotive Q cycle. Energy transduction by coupling of proton translocation to electron transfer by the cytochrome bc1 complex. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1990;265:11409–11412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mitchell P. Possible molecular mechanisms of the protonmotive function of cytochrome systems. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 1976;62:327–367. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(76)90124-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ljungdahl PO, Pennoyer JD, Robertson DE, Trumpower BL. Purification of highly active cytochrome bc1 complexes from phylogenetically diverse species by a single chromatophaphic procedure. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1987;891:227–241. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(87)90218-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu L, Tso SC, Shenoy SK, Quinn BN, Xia D. The role of the supernumerary subunit of Rhodobacter sphaeroides cytochrome bc1 complex. Journal of Bioenergetics and Biomembranes. 1999;31:251–257. doi: 10.1023/a:1005423913639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xia D, Yu CA, Kim H, Xia JZ, Kachurin AM, Zhang L, Yu L, Deisenhofer J. Crystal structure of the cytochrome bc1 complex from bovine heart mitochondria. Science. 1997;277:60–66. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5322.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Esser L, Quinn B, Li Y, Zhang M, Elberry M, Yu L, Yu CA, Xia D. Crystallographic studies of quinol oxidation site inhibitors: A modified classification of inhibitors for the cytochrome bc1 complex. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2004;341:281–302. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang LS, Cobessi D, Tung EY, Berry EA. Binding of the respiratory chain inhibitor antimycin to the mitochondrial bc1 complex: a new crystal structure reveals an altered intramolecular hydrogen-bonding pattern. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2005;351:573–597. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.05.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elberry M, Xiao K, Esser L, Xia D, Yu L, Yu CA. Generation, characterization and crystallization of a highly active and stable cytochrome bc1 complex mutant from Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1757:835–840. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2006.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berry EA, Huang L, Saechao LK, Pon NG, Valkova-Valchanova M, Daldal F. X-ray structure of Rhodobacter capsulatus cytochrome bc1: comparison with its mitochondrial and chloroplast counterparts. Photosynthesis Research. 2004;81:251–275. doi: 10.1023/B:PRES.0000036888.18223.0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Esser L, Gong X, Yang S, Yu L, Yu CA, Xia D. Surface-modulated motion switch: capture and release of iron-sulfur protein in the cytochrome bc1 complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:13045–13050. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601149103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tian H, Yu L, Mather MW, Yu CA. Flexibility of the neck region of the rieske iron-sulfur protein is functionally important in the cytochrome bc1 complex. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273:27953–27959. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.43.27953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Darrouzet E, Valkova-Valchanova M, Daldal F. Probing the role of the Fe-S subunit hinge region during Q(o) site catalysis in Rhodobacter capsulatus bc(1) complex. Biochemistry. 2000;39:15475–15483. doi: 10.1021/bi000750l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tian H, Yu L, Mather MW, Yu CA. The Involvement of Serine 175 and Alanine 185 of Cytochrome b of Rhodobacter sphaeroides Cytochrome bc1 Complex in Interaction with Iron-Sulfur Protein. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:23722–23728. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.38.23722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iwata S, Lee JW, Okada K, Lee JK, Iwata M, Rasmussen B, Link TA, Ramaswamy S, Jap BK. Complete structure of the 11-subunit bovine mitochondrial cytochrome bc1 complex [see comments] Science. 1998;281:64–71. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5373.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xia D, Kim H, Yu CA, Yu L, Kachurin A, Zhang L, Deisenhofer J. A novel electron transfer mechanism suggested by crystallographic studies of mitochondrial cytochrome bc1 complex. Biochemistry and Cell Biology. 1998;76:673–679. doi: 10.1139/bcb-76-5-673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim H, Xia D, Yu CA, Xia JZ, Kachurin AM, Zhang L, Yu L, Deisenhofer J. Inhibitor binding changes domain mobility in the iron-sulfur protein of the mitochondrial bc1 complex from bovine heart. Proceedings of National Academy of Sciences U S A. 1998;95:8026–8033. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.8026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hunte C, Koepke J, Lange C, Rossmanith T, Michel H. Structure at 2.3 A resolution of the cytochrome bc(1) complex from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae co-crystallized with an antibody Fv fragment. Structure. 2000;15:669–684. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00152-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deisenhofer J, Michel H. The Photosynthetic Reaction Center from the Purple Bacterium Rhodopseudomonas viridis. SCIENCE. 1989;245:1463–1473. doi: 10.1126/science.245.4925.1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ostermeier C, Harrenga A, Ermler U, Michel H. Structure at 2.7 A resolution of the Paracoccus denitrificans two-subunit cytochrome c oxidase complexed with an antibody FV fragment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:10547–10553. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.20.10547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xiao K, Yu L, Yu CA. Confirmation of the involvement of protein domain movement during the catalytic cycle of the cytochrome bc1 complex by the formation of the intersubunit disulfide bond between cytochrome b and the iron-sulfur protein. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275:38597–38604. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007444200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guo F, Esser L, Singh SK, Maurizi MR, Xia D. Crystal Structure of the Heterodimeric Complex of the Adaptor, ClpS, with the N-domain of the AAA+ Chaperone, ClpA. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277:46753–46762. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208104200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]