Abstract

Adults aged 50 and older make up half of individuals experiencing homelessness and have high rates of morbidity and mortality. They may have different life trajectories and reside in different environments than do younger homeless adults. Although the environmental risks associated with homelessness are substantial, the environments in which older homeless individuals live have not been well characterized. We classified living environments and identified associated factors in a sample of older homeless adults. From July 2013 to June 2014, we recruited a community-based sample of 350 homeless men and women aged fifty and older in Oakland, California. We administered structured interviews including assessments of health, history of homelessness, social support, and life course. Participants used a recall procedure to describe where they stayed in the prior six months. We performed cluster analysis to classify residential venues and used multinomial logistic regression to identify individual factors prior to the onset of homelessness as well as the duration of unstable housing associated with living in them. We generated four residential groups describing those who were unsheltered (n=162), cohabited unstably with friends and family (n=57), resided in multiple institutional settings (shelters, jails, transitional housing) (n=88), or lived primarily in rental housing (recently homeless) (n=43). Compared to those who were unsheltered, having social support when last stably housed was significantly associated with cohabiting and institution use. Cohabiters and renters were significantly more likely to be women and have experienced a shorter duration of homelessness. Cohabiters were significantly more likely than unsheltered participants to have experienced abuse prior to losing stable housing. Pre-homeless social support appears to protect against street homelessness while low levels of social support may increase the risk for becoming homeless immediately after losing rental housing. Our findings may enable targeted interventions for those with different manifestations of homelessness.

Keywords: United States, Homelessness, ageing, cluster analysis, environmental health, gender, social support, housing

INTRODUCTION

Over the past thirty years the median age of adult homeless individuals in the United States has increased from the late twenties to approximately fifty. This trend has continued beyond what would be expected by the aging of the general population (Culhane et al., 2010; Hahn et al., 2006). As the age structure of the homeless population shifted, so did the health characteristics of people experiencing homelessness. Among older homeless adults, there are high rates of chronic diseases, cognitive and functional impairments (Brown et al., 2012; Garibaldi et al., 2005). Homelessness is associated with increased morbidity (Fazel et al., 2014; Hwang, 2001) and early mortality (Barrow et al., 1999; Hibbs et al., 1994; Hwang et al., 2009; Metraux et al., 2011), although the risk that homelessness imparts goes beyond poverty, demographic background, health behaviors, and insurance coverage (Browning & Cagney, 2003; Morrison, 2009), suggesting an important role of the lived environment.

The definition of homelessness in the Homeless Emergency Assistance and Rapid Transition to Housing (HEARTH) Act includes both those who lack a fixed residence or reside in a place not typically used for sleeping and those who are at imminent risk of losing housing within fourteen days ("Homeless Emergency Assistance and Rapid Transition to Housing Act of 2009. Definition of homelessness.," 2009). The HEARTH Act acknowledges that people experiencing homelessness reside in a variety of environments including unsheltered environments, shelters, residential hotels, temporary stays with friends and family, jails, hospitals, and treatment programs. The lived environment plays a significant role in defining the experience of homelessness and homeless survival (Marr et al., 2009; Wolch et al., 1988). These environments may result in different patterns of exposure to environmental risks and access to health and social services, yet little is known about where people experiencing homelessness reside and whether there are differences in the characteristics of people who live in different environments (O'Flaherty, 2012).

The role of safe environments may be particularly important for older adults, as disability results from an interaction between physical impairment and the environment (Verbrugge & Jette, 1994). Poor household and neighborhood conditions have been associated with poorer physical functioning in older people (Lan et al., 2009; Samuel et al., 2015). Although such individuals may rely on environmental modifications and external supports to mitigate impairments, homelessness impedes the ability to control one’s environment (Kushel, 2012).

Previous work has used typologies of homelessness to understand the choices made by individuals who experience homelessness and the actions of the institutional structures that were established to serve them (Adlaf & Zdanowicz, 1999; Farrow et al., 1992; Jahiel & Babor, 2011), the most enduring of which is a time-aggregated approach describing chronic, episodic, and transitional patterns of homelessness using shelter data from New York City (Kuhn & Culhane, 1998). Shelters however house only a subpopulation of homeless individuals. We hypothesized that the lived environment during homelessness is heterogeneous and that those residing in different environments may share certain strengths and vulnerabilities. We developed an environmental typology using cluster analysis as a lens to explore how individual impairments and strengths are related to structural factors and institutional actors, theorizing that understanding residential patterns will help us better understand the complex dynamics between individual factors and structural factors (DeVerteuil, 2003).

Using baseline data from the Health Outcomes of People Experiencing Homelessness in Older Middle Age (HOPE HOME) cohort, we define and describe four clusters of residential venues in older homeless adults. We examine duration of unstable housing and homelessness, demographic factors, and behavioral and situational factors prior to the loss of the last stable housing associated with each of these residential patterns. Defining residential patterns and determining factors associated with them may allow for more targeted service delivery and further elucidate the role of the lived environment in mediating the morbidity and chronicity of homelessness.

METHODS

Sampling and Inclusion Criteria

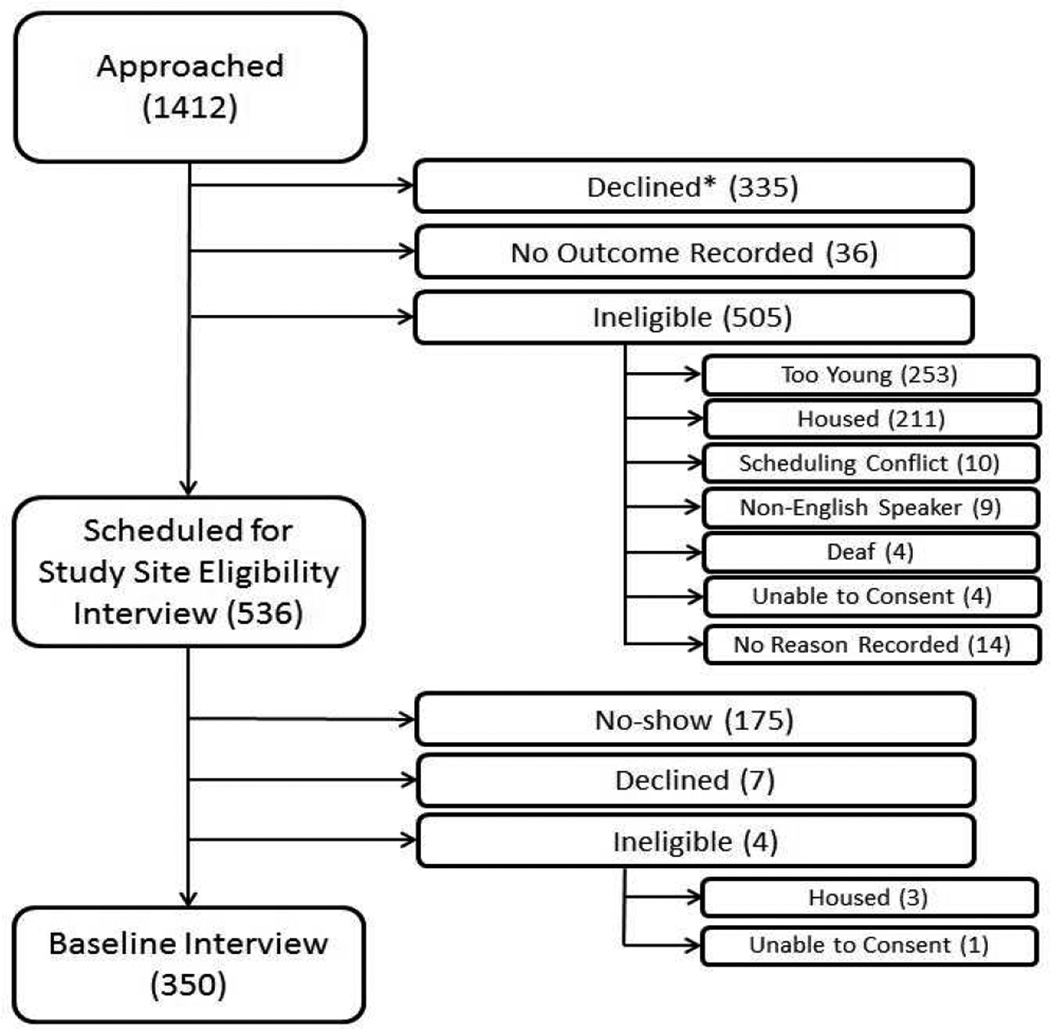

From July 2013 to June 2014, we conducted community-based sampling of 350 homeless individuals aged 50 and older in Oakland CA. Similar to our prior research with homeless adults, we sampled from homeless shelters and free meal programs (Hansen et al., 2011; Palar et al., 2014; Vijayaraghavan et al., 2013a; Vijayaraghavan et al., 2013b; Vogenthaler et al., 2013; Weiser et al., 2009; Weiser et al., 2013a; Weiser et al., 2013b). We also included homeless encampments and recycling centers because of concerns among key informants that some individuals would not be represented adequately (Figure 1). We sampled from all overnight homeless shelters in Oakland that served single adults over the age of 25 (n=5), all free and low-cost meal programs that served homeless individuals at least 3 meals a week (n=5), one recycling center close to homeless service agencies, and homeless encampments throughout Oakland. To recruit participants from homeless encampments, the study team followed an outreach van that served homeless individuals on randomly selected shifts and enrolled participants at each stop. At other sites, we used random sampling of individuals from each venue, based on the number of unique individuals estimated to be served annually at that site. If the designated person declined, was ineligible, or already in the study, we approached the next person until we identified an eligible individual. Someone from the primary recruitment team was present for enrollment interviews to ensure that participants were not double-counted. Inclusion criteria included English-speaking, age 50 or older, and defined as currently homeless by the HEARTH Act (lacked a fixed residence, resided in a place not typically used for sleeping, or were imminently at risk of losing housing within fourteen days) ("Homeless Emergency Assistance and Rapid Transition to Housing Act of 2009. Definition of homelessness.," 2009). At meal programs, encampments and recycling centers, staff asked individuals where they had stayed for the last 2 weeks to establish homelessness. Individuals residing in shelters were presumed to be homeless. Study staff provided a brief description of the study and invited potential participants to a visit for more intensive screening at a community center that served lower-income adults. Individuals who presented for the study visit underwent another screening procedure to confirm homelessness and evaluate the ability to consent to the study. The study protocol was approved by the University of California, San Francisco Institutional Review Board.

Figure 1.

Sampling Strategy for the HOPE-HOME Cohort of Older Homeless Adults, Oakland CA (N=350)

*Participants who declined after being approached (335) declined before being assessed for eligibility. Therefore, the number of participants who were ineligible for the study may have been higher than the numbers presented in this table.

Measures

We gathered demographic data from participants, including age, gender, race, veteran status, and highest level of educational attainment. Participants reported whether they experienced homelessness before the age of eighteen, the age at which they first became homeless in adulthood, and the duration of their current episode of homelessness, defined as the time since meeting the HEARTH criteria definition.

Events during the target year

We asked participants to report on their experiences during the ‘target year,’ the last year in which participants were stably housed (housed in a non-institutional setting for 12 months or more) (Shinn et al., 2007). This construct is distinct from the time since the current onset of homelessness. We asked where participants had stayed and the reasons why they left, which we used for descriptive purposes only (Burt et al., 1999). We asked participants to report whether they had suffered verbal, physical, or sexual abuse during the target year. We assessed social support by asking participants whether they had someone to stay with or someone who would lend them money if needed, and used those responses to create an instrumental support index ranging from 0–2 (Gielen et al., 1994). We also asked about the receipt of government financial assistance, case management services, health insurance, and primary care during the target year and coded positive values for each as a binary measure.

History of substance use, mental health problems and incarceration through the end of the target year

To measure substance use disorders and mental health problems, we adapted questions from the Addiction Severity Index (ASI), 5th Edition (McLellan et al., 1992). We asked participants about alcohol, cocaine, methamphetamines, and use of non-prescribed opioids throughout the life course and at what age they started using each regularly, defined as using at least three times per week. We coded responses as positive for each substance if they had used it regularly prior to the end of their target year. We asked participants if they had ever experienced serious depression, anxiety, or thoughts of suicide. If participants reported any such experiences, we asked them to report the first and most recent times. We asked participants to report whether and when they had sought treatment for their mental health problems (Burt et al., 1999) and coded responses as positive if they had experienced problems or attended treatment prior to the end of the target year. We asked participants if they had ever spent time in jail or prison and if so, when, and created a binary variable for incarceration prior to the end of the target year.

Residential History

We gathered residential histories based on the Residential Time-Line Follow-Back Inventory (Tsemberis et al., 2007). Study staff asked the participant to recount all of the places they had stayed in the past 6 months, prompting recall by reviewing all venues (shelters; on streets; with friends and family; transitional housing; rented or owned rooms, apartments, or homes; hotels and single-room occupancy (SRO) units; medical facilities; drug rehabilitation facilities; jails or prison). Participants gave a numerical value (0–180) for the number of days spent in each.

Cluster Analysis

Using the six-month residential recall, we performed cluster analysis to develop a classification of the type of housing in which participants lived. Cluster analysis (Everitt et al., 2011; Kaufman & Rousseeuw, 1990) finds existing patterns within data to generate groups by minimizing within-group and maximizing between-group variability and has been used in studies of homelessness to classify subpopulations (Danseco & Holden, 1998; Huntington et al., 2008; Kuhn & Culhane, 1998). Using Stata version 11 (StataCorp, 2009), we employed two cluster methods to determine the classification of housing status for participants. First, we used Ward’s linkage to minimize the sum-of-square differences within groups (Hair et al., 1987; Ward, 1963). To select an optimal number of clusters, we performed visual analysis of a dendrogram representing the structure of the data and confirmed that we could identify natural groupings using bivariate matrices which provided construct validation. Next, we used the k-medians cluster methodology with a Euclidean distance similarity measure (L2) to verify cluster classifications, for a set number of k clusters ranging from 3–8 (Brusco & Köhn, 2009; Kohn et al., 2010). We used the Calinski pseudo-F statistic, which measures the ratio of between cluster variance to within cluster variance as a quantitative measure of the distinctness of the groups generated by the cluster analysis and provide a stopping rule to optimize the number of groups selected (Calinski & Harabasz, 1974).

Analysis

We performed data analysis using Stata version 11 (StataCorp, 2009). We performed non-parametric analysis of variance and chi-square testing to compare group characteristics between clusters (Kruskal & Wallis, 1952). Following the bivariate analysis, we retained covariates with P<0.20 and removed collinear variables. The remaining variables were used in a multinomial logistic regression model to determine factors associated with each cluster. We calculated multinomial logit coefficients and present their exponentiated values as adjusted risk ratios (ARR) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals and P values to determine significant differences between covariates for each cluster when compared with the largest cluster which was used as a baseline risk group. We tested for interactions and selected a final model based on Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC) which favors models with improved fit (log-likelihood) and penalizes model overfitting (Akaike, 1998). As the interaction models did not contribute to the overall model fit, we did not include them in the final analysis.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

The sample was predominantly African-American (79.7%) and men (77.1%) (Table 1) with a median age of 58 years (range 50–80); 43.5% had become homeless at age 50 or later. Half of the sample (50.3%) had been homeless during this episode for greater than one year yet two-thirds of participants (67.2%) had lost their last stable housing more than a year ago. Prior to the end of the target year, most participants had a history of cocaine (70.6%) or alcohol (56.9%) use. Approximately half had experienced depression (50.6%) and slightly less had experienced anxiety (44.0%). The majority of participants (78.9%) had a history of incarceration at some point prior to losing stable housing. During the last year of stable housing, one-fifth (21.1%) of the sample had experienced a form of abuse. The majority of respondents had social support during the last period of stable housing: 64.8% had someone to stay with and 69.0% had someone to lend them money. The reasons for losing stable housing included interpersonal conflicts with other housemates (10.9%), the end of a relationship (11.4%) and eviction unrelated to the ability to pay (12.3%). Approximately a third of the sample cited difficulty with paying rent; 13.4% were unable to pay their own rent whereas 15.7% reported someone else’s inability to pay.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics in the HOPE HOME Cohort of Homeless adults aged 50 and older (N=350)

| No. | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Age, y | ||

| 50–54 | 102 | 29.1 |

| 55–59 | 117 | 33.4 |

| 60–64 | 89 | 25.4 |

| 65 or greater | 42 | 12.0 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 80 | 22.9 |

| Race | ||

| Non-Latino white | 38 | 10.9 |

| Non-Latino African American | 279 | 79.7 |

| Latino | 16 | 4.6 |

| Other | 17 | 4.9 |

| Veteran | 76 | 21.7 |

| Highest Completed Education | ||

| Less than High School | 91 | 26.0 |

| High School or GED Degree | 181 | 51.7 |

| Post-Secondary Degree | 78 | 22.3 |

| History of Homelessness | ||

| Homeless as a Child | 8 | 2.3 |

| Duration of Homeless Episode | ||

| Age First Homeless in Adulthood | ||

| 18–25 | 52 | 14.9 |

| 26–49 | 146 | 41.7 |

| 50–59 | 115 | 32.9 |

| 60 or greater | 37 | 10.6 |

| Duration of Current Episode of Homelessness | ||

| Less than 3 months | 78 | 22.3 |

| 3 months to < 6 months | 37 | 10.6 |

| 6 months to < 12 months | 59 | 16.9 |

| 12 months to < 4 years | 99 | 28.3 |

| 4 years or greater | 77 | 22.0 |

| Duration Since Last Period of Stable Housing (Target Year) | ||

| Less than 3 months | 37 | 10.6 |

| 3 months to < 6 months | 25 | 7.1 |

| 6 months to < 12 months | 53 | 15.1 |

| 12 months to < 4 years | 120 | 34.3 |

| 4 years or greater | 115 | 32.9 |

| Substance Abusea Before Losing Stable Housingb | ||

| Regular Alcohol Use | 199 | 56.9 |

| Regular Cocaine Use | 247 | 70.6 |

| Regular Amphetamine Use | 89 | 25.4 |

| Regular Opioid Use | 86 | 24.6 |

| Mental Illness Before Losing Stable Housingc | ||

| Depression | 177 | 50.6 |

| Anxiety | 154 | 44.0 |

| Suicidal Thoughts | 66 | 18.9 |

| Psychiatric Hospitalization Before Homeless | 46 | 13.1 |

| Incarceration Before Losing Stable Housing | 276 | 78.9 |

| Abuse During Year of Last Stable Housing | ||

| Verbal | 48 | 13.7 |

| Physical | 45 | 12.9 |

| Sexual | 16 | 4.6 |

| Any | 74 | 21.1 |

| Social Supports During Period of Last Stable Housing | ||

| Had Someone to Lend Money (%) | 240 | 69.0 |

| Had Someone to Stay With (%) | 223 | 64.8 |

| Institutional Supports During Period of Last Stable Housing | ||

| Received Government Benefits or Social Security | 246 | 70.3 |

| Had a Primary Care Clinic | 183 | 52.3 |

| Had Health Insurance | 235 | 67.1 |

| Had a Case Manager | 41 | 11.7 |

| Reason Lost Stable Housing | ||

| Never had Stable Housing | 4 | 1.1 |

| Couldn't Pay Rent/Mortgage | 47 | 13.4 |

| Someone Else Stopped Paying Rent/Mortgage | 55 | 15.7 |

| Family Abuse/Violence | 5 | 1.4 |

| Pushed or Kicked Out, for Reasons Other than Payment | 3 | 0.9 |

| Building Condemned/Destroyed/Foreclosed | 18 | 5.1 |

| Moved Elsewhere (to a new city/with someone else) | 32 | 9.1 |

| Enrolled in a Hospital or Drug Treatment Program | 4 | 1.1 |

| Incarcerated or Imprisoned | 16 | 4.6 |

| Poor or Unsafe Housing Conditions | 23 | 6.6 |

| Evicted by Landlord or Asked to Move Out | 43 | 12.3 |

| Break-up or Death or Spouse/Partner | 40 | 11.4 |

| Housemates Using Drugs, Alcohol, or Stealing | 5 | 1.4 |

| Personal Use of Drugs or Alcohol | 13 | 3.7 |

| Conflict With Others in the Household | 38 | 10.9 |

| Mental/Emotional Crisis | 2 | 0.6 |

| No Reason Given | 2 | 0.6 |

History of use three times per week or greater, initiated prior to the end of the target year, the last year in which participants had stable housing for 12 months

Stable housing defined as living in an apartment or house with tenancy rights, staying with family or friends for free or for rent, or a hotel or motel with tenancy rights

Experienced symptoms of mental illness at any time prior to the end of the target year, the last year in which participants had stable housing for 12 months

Cluster Analysis

We found the optimal cluster solutions to be comprised of either four or six groups. There was a high correlation between the cluster solutions using both Ward’s linkage and k-medians, with correlation coefficients of 90% and 95% for the four- and six-group solutions, respectively. We used the four-group k-medians cluster solution for the final analysis as it generated groups with the most similar sizes and distinguished four distinct and meaningful groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Days in Each Housing Type During the Past 180 Days, by Cluster N=350 (mean, (SD))

| Unsheltereda n=162 |

Cohabitersb n=57 |

Multiple Institution Usersc n=88 |

Rentersd n=43 |

Pe | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days by Housing Type | |||||

| Unsheltered | 154.2 (28.08) | 22.3 (31.6) | 28.4 (31.3) | 12.9 (19.5) | <0.001 |

| In Shelter | 7.9 (16.1) | 21.7 (26.4) | 71.0 (59.7) | 14.7 (23.4) | <0.001 |

| Transitional Housing | 0.3 (2.0) | 0.0 (0.1) | 17.1 (43.2) | 0.7 (4.6) | <0.001 |

| Hotel | 4.2 (9.9) | 3.8 (10.4) | 23.8 (44.2) | 4.9 (10.9) | 0.024 |

| Rented Apartment or Room | 2.5 (11.2) | 3.4 (12.0) | 4.3 (15.4) | 144.4 (23.8) | <0.001 |

| Owned Home | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4.2 (23.5) | 0 (0) | 0.03 |

| With Friends or Family | 7.7 (15.1) | 128.1 (32.7) | 11.2 (19.0) | 4.0 (11.1) | <0.001 |

| Medical Facility | 1.9 (6.4) | 3.1 (19.9) | 2.0 (6.5) | 0.6 (2.4) | 0.123 |

| Drug Facility | 0.3 (4.3) | 0 (0) | 2.4 (13.5) | 0 (0) | 0.136 |

| Jail or Prison | 2.6 (11.1) | 0.9 (6.0) | 14.5 (40.4) | 0.7 (4.6) | 0.009 |

Unsheltered cluster spent the majority of days unsheltered (on the street or other place not ordinarily used as sleeping accommodations)

Cohabitors spent the majority of days staying with friends or family

Multiple Institution Users spent the majority of days in shelters, jail, transitional housing, and other institutions

Renters spent the majority of days in rented rooms or apartments

Non Parametric ANOVA

The largest cluster (n=162) spent the majority of days in the prior six months (85.7%) unsheltered (“unsheltered”). A second cluster (n=57) spent the majority of days (71.2%) residing in the homes of friends and family members, either for free or paying rent (“cohabiters”). A third group (n=88) spent time in a variety of places, including homeless shelters (39.4% of days), incarcerated, and transitional housing (“multiple institution users”). The smallest cluster (n=43) resided primarily in rental housing (80.2%) and spent a minority of time living on the streets (7.2% of days) or in shelters (8.2% of days) (“renters”). We found significant between-group differences in the number of days spent in all residential venues with the exception of medical facilities and drug rehabilitation facilities. The six-group cluster solutions resulted in further partitioning of the multiple institution users cluster into three separate groups, which did not substantively alter the typology of institution use [INSERT LINK TO ONLINE FILE Supplementary Table.xlsx].

Cluster Characteristics

There were no significant differences in age, race, or educational attainment between the clusters (Table 3). Women were overrepresented in the cohabiters (45.6%) and renters groups (32.6%, P<0.001). The mean duration of this episode of homelessness was significantly greater in the unsheltered and multiple institution user clusters than the cohabiters and renters (P<0.001), corresponding with older ages of entry into first adult homelessness for the latter two groups. A significantly greater proportion of the renters became homeless after the age of 60 (25.6%, P=0.004). Although the majority (57.9%) of cohabiters reported this episode of homelessness as less than six months in duration, three-quarters of the cohabiters (77.1%) reported their last stable housing having occurred more than six months previously. We did not find substantial differences between duration of the current episode of homelessness and last stable housing in the other groups. There were no significant differences between the groups in mental health problems or psychiatric hospitalizations prior to losing stable housing. During the last period of stable housing, instrumental support was highest in the cohabiters (1.6) and lowest in the renters cluster (1.2, P=0.04). Utilization of institutional supports during the last period of stable housing was similar across the groups with the exception of primary care services, which were lowest in the unsheltered cluster (43.2%, P=0.009).

Table 3.

HOPE HOME Characteristics by Residential Cluster (N=350)

| Unsheltereda | Cohabitersb | Multiple Institution Usersc |

Rentersd | Pe | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics, n (%) | |||||

| Age, Current | |||||

| 50–54 | 49 (30.3) | 22 (38.6) | 24 (27.3) | 7 (16.3) | |

| 55–59 | 53 (32.7) | 17 (29.8) | 32. (36.4) | 15 (34.9) | |

| 60–64 | 45 (27.8) | 14 (24.6) | 19 (21.6) | 11 (25.6) | |

| 65 or greater | 15 (9.3) | 4 (7.0) | 13 (14.8) | 10 (23.3) | 0.161 |

| Female | 23 (14.2) | 26 (45.6) | 17 (19.3) | 14 (32.6) | <0.001 |

| Race | |||||

| Non-Latino white | 16 (9.9) | 4 (7.0) | 10 (11.4) | 8 (18.6) | |

| Non-Latino African American | 133 (82.1) | 45 (79.0) | 71 (80.7) | 30 (69.8) | |

| Latino | 8 (4.9) | 3 (5.3) | 4 (4.6) | 1 (2.3) | |

| Other | 5 (3.1) | 5 (8.8) | 3 (3.4) | 4 (9.3) | 0.389 |

| Veteran | 36 (27.2) | 7 (12.3) | 23 (26.1) | 9 (20.9) | 0.255 |

| Highest Completed Education | |||||

| Less than High School | 46 (28.4) | 12 (21.1) | 24 (27.3) | 9 (20.9) | |

| High School Degree or GED | 84 (51.9) | 31 (54.4) | 43 (48.9) | 23 (53.5) | |

| Post-Secondary Degree | 32 (19.8) | 14 (24.6) | 21 (23.9) | 11 (25.6) | 0.866 |

| History of Homelessness, n (%) | |||||

| Homeless as a Child | 5 (3.1) | 1 (1.8) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (2.3) | 0.787 |

| Age First Homeless in Adulthood | |||||

| 18–25 | 25 (15.4) | 6 (10.5) | 16 (18.2) | 5 (11.6) | |

| 26–49 | 78 (48.2) | 18 (31.6) | 38 (43.2) | 12 (27.9) | |

| 50–59 | 51 (31.5) | 24 (42.1) | 25 (28.4) | 15 (34.9) | |

| 60 or greater | 8 (4.9) | 9 (15.8) | 9 (10.2) | 11 (25.6) | 0.004 |

| Duration of Homeless Episode | |||||

| Less than 3 months | 5 (3.1) | 22 (38.6) | 16 (16.2) | 35 (81.4) | |

| 3 months to < 6 months | 11 (6.8) | 11 (19.3) | 11 (12.5) | 4 (9.3) | |

| 6 months to < 12 months | 33 (20.4) | 6 (10.5) | 20 (22.7) | 0 (0) | |

| 12 months to < 4 years | 60 (37.0) | 11 (19.3) | 26 (29.6) | 2 (4.7) | |

| 4 years or greater | 53 (32.7) | 7 (12.3) | 15 (17.1) | 2 (4.7) | <0.001 |

|

Duration Since Last Period of Stable Housing (Target Year) |

|||||

| Less than 3 months | 2 (1.2) | 6 (10.5) | 6 (6.8) | 23 (53.5) | |

| 3 months to < 6 months | 6 (3.7) | 7 (12.3) | 7 (8.0) | 5 (11.6) | |

| 6 months to < 12 months | 22 (13.6) | 17 (29.8) | 12 (13.6) | 2 (4.7) | |

| 12 months to < 4 years | 59 (36.4) | 17 (29.8) | 36 (40.9) | 8 (18.6) | |

| 4 years or greater | 73 (45.1) | 10 (17.5) | 27 (30.7) | 5 (11.6) | <0.001 |

|

Substance Abuse Before Losing Stable Housing,f n (%) |

|||||

| Regular Alcohol Use | 88 (54.3) | 32 (56.1) | 53 (60.2) | 26 (60.5) | 0.784 |

| Regular Cocaine Use | 22 (75.3) | 43 (75.4) | 53 (60.2) | 29 (67.4) | 0.068 |

| Regular Amphetamine Use | 36 (23.5) | 14 (24.6) | 17 (19.3) | 20 (46.5) | 0.007 |

| Regular Opioid Use | 43 (26.5) | 16 (28.1) | 15 (17.1) | 12 (27.9) | 0.301 |

|

Mental Illness Before Losing Stable Housing,g n (%) |

|||||

| Depression | 78 (48.2) | 32 (56.1) | 47 (53.4) | 20 (46.5) | 0.647 |

| Anxiety | 70 (43.2) | 26 (45.6) | 39 (44.3) | 19 (44.2) | 0.991 |

| Suicidal Thoughts | 24 (14.8) | 10 (17.5) | 23 (26.1) | 9 (20.9) | 0.175 |

| Psychiatric Hospitalization Before Homeless |

17 (10.5) | 7 (12.3) | 17 (19.3) | 5 (11.6) | 0.255 |

|

Incarceration Before Losing Stable Housing, n (%) |

135 (83.3) | 45 (79.0) | 67 (76.1) | 29 (67.4) | 0.127 |

|

Abuse During Year of Last Stable Housing, n (%) |

|||||

| Verbal | 17 (10.5) | 12 (21.1) | 10 (11.4) | 9 (20.9) | 0.097 |

| Physical | 17 (10.5) | 12 (21.1) | 9 (10.2) | 7 (16.3) | 0.157 |

| Sexual | 4 (2.5) | 5 (8.8) | 4 (4.6) | 3 (7.0) | 0.211 |

| Any | 28 (17.3) | 18 (31.6) | 16 (18.2) | 12 (27.9) | 0.078 |

|

Social Supports During Period of Last Stable Housing |

|||||

| Had Someone to Lend Money, n (%) | 104 (64.6) | 44 (77.2) | 64 (73.6) | 28 (65.1) | 0.222 |

| Had Someone to Stay With, n (%) | 98 (62.0) | 44 (78.6) | 59 (67.8) | 22 (51.2) | 0.029 |

| Instrumental Support Indexh (Mean, 95% CI)i |

1.26 (1.13–1.39) |

1.55 (1.37–1.74) |

1.41 (1.26–1.57) |

1.16 (0.91–1.41) |

0.044 |

|

Institutional Supports During Period of Last Stable Housing, n(%) |

|||||

| Received Government Benefits or Social Security |

109 (67.3) | 41 (71.9) | 62 (70.5) | 34 (79.1) | 0.501 |

| Had a Primary Care Clinic | 70 (43.2) | 31 (54.4) | 53 (60.2) | 29 (56.4) | 0.009 |

| Had Insurance | 101 (62.4) | 38 (66.7) | 62 (70.5) | 34 (79.1) | 0.179 |

| Had a Case Manager | 15 (9.3) | 6 (10.5) | 14 (15.9) | 6 (14.0) | 0.436 |

| Reason Lost Stable Housing, n (%) | |||||

| Never had Stable Housing | 2 (1.2) | 0 (0) | 2 (2.3) | 0 (0) | |

| Couldn't Pay Rent/Mortgage | 23 (14.2) | 8 (14.0) | 6 (6.8) | 10 (23.3) | |

| Someone Else Stopped Paying Rent/Mortgage |

25 (15.4) | 13 (22.8) | 11 (12.5) | 6 (14.0) | |

| Family Abuse/Violence | 2 (1.2) | 3 (5.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Pushed or Kicked Out, for Reasons Other than Payment |

1 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (2.3) | |

| Building Condemned/Destroyed/Foreclosed | 9 (5.6) | 3 (5.3) | 4 (4.6) | 2 (4.7) | |

| Moved Elsewhere (to a new city/with someone else) |

13 (8.0) | 5 (8.8) | 9 (10.2) | 5 (11.6) | |

| Enrolled in a Hospital or Drug Treatment Program |

2 (1.2) | 1 (1.8) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0) | |

| Incarcerated or Imprisoned | 9 (5.6) | 2 (3.5) | 5 (5.7) | 0 (0) | |

| Poor or Unsafe Housing Conditions | 7 (4.3) | 2 (3.5) | 10 (11.4) | 4 (9.3) | |

| Evicted by Landlord/Asked to Move Out | 14 (8.6) | 10 (17.5) | 13 (14.8) | 4 (9.3) | |

| Break-up or Death or Spouse/Partner | 25 (15.4) | 3 (5.3) | 9 (10.2) | 3 (7.0) | |

| Housemates Using Drugs, Alcohol, or Stealing | 0 (0) | 1 (1.8) | 3 (3.4) | 1 (2.3) | |

| Personal Use of Drugs or Alcohol | 8 (4.9) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (4.6) | 1 (2.3) | |

| Conflict With Others in the Household | 19 (11.7) | 5 (8.8) | 10 (11.4) | 4 (9.3) | |

| Mental/Emotional Crisis | 2 (1.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| No Reason Given | 1 (0.6) | 1 (1.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.332 |

Unsheltered cluster spent the majority of days unsheltered (on the street or other place not ordinarily used as sleeping accommodations)

Cohabitors spent the majority of days staying with friends or family

Multiple Institution Users spent the majority of days in shelters, jail, transitional housing, and other institutions

Renters spent the majority of days in rented rooms or apartments

Chi-Square Analysis

History of use three times per week or greater, initiated prior to the end of the target year

Experienced symptoms at any time prior to the end of the target year

Sum of responses to having someone to lend money and someone to stay with (range 0–2), derived from Gielen et al. (2004)29

Non-Parametric ANOVA

Factors Associated with Residential Clusters

After adjustment, compared to the unsheltered cluster, factors associated with being in the cohabiters cluster were being a woman (ARR 5.7, P<0.001), older age of first homelessness (ARR 1.04 per year, P=0.04), shorter duration since last stably housed (ARR 0.9 per year, P=0.03) and greater instrumental support (ARR 2.1, P=0.004) (Table 4). The cohabiters cluster was associated with significantly greater experiences of abuse during the last period of stable housing (ARR 2.2, P=0.049). Factors associated with being in the renters cluster versus the unsheltered cluster were older age (ARR 1.1 per year, P=0.03), being a woman (ARR 2.8, P=0.03), and shorter duration since last stably housed (ARR 0.8 per year, P=0.01). History of amphetamine use prior to homelessness was significantly associated with being in the renters cluster (ARR 5.1, P<0.001). Members of the renters cluster were less likely to have a history of incarceration, which approached statistical significance (ARR 0.4, P=0.050). The multiple institution users were similar when compared to the unsheltered cluster members, but were associated with greater social support (ARR 1.6, P=0.02) and a history of suicidal thoughts (ARR 2.3, P=0.02) and negatively associated with regular cocaine use prior to losing stable housing (ARR 0.4, P=0.008).

Table 4.

Factors Associated with Membership in Clusters in the HOPE HOME Cohort - Multivariate Results: Multinomial Log Odds Comparing Clusters to Unsheltered Cluster (N=350)f

| Cohabitersg vs Unshelteredh ARR (95% CI) |

Multiple Institution Usersi vs Unsheltered ARR (95% CI) |

Rentersj vs Unsheltered ARR (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Agea | 0.96 (0.88–1.03) | 1.04 (0.97–1.10) | 1.09* (1.01–1.17) |

| Female Sexb | 5.72*** (2.61–12.54) | 1.19 (0.55–2.58) | 2.84* (1.14–7.12) |

| Age First Homelessa | 1.04* (1.00–1.07) | 0.99 (0.97–1.02) | 1.01 (0.98–1.04) |

| Years Since Last Stably Houseda | 0.93* (0.86–0.99) | 0.99 (0.96–1.03) | 0.84* (0.73–0.96) |

| History of Amphetamine Useb,d | 1.20 (0.53–2.76) | 0.90 (0.44–1.85) | 5.14*** (2.18–12.09) |

| History of Cocaine Useb,d | 0.60 (0.25–1.43) | 0.40** (0.21–0.79) | 0.45 (0.17–1.16) |

| History of Suicidal Thoughtsb,e | 0.88 (0.34–2.28) | 2.27* (1.11–4.63) | 1.09 (0.40–2.99) |

| History of Incarcerationb | 0.74 (0.28–1.93) | 0.56 (0.26–1.20) | 0.37 (0.14–1.00) |

| Abuse During Target Yearb | 2.18* (1.00–4.75) | 0.99 (0.48–2.05) | 1.75 (0.72–4.26) |

| Social Supports During Last Stable Housing Instrumental Support Indexc |

2.05** (1.25–3.36) | 1.59* (1.09–2.31) | 1.13 (0.70–1.83) |

| Institutional Supports During Last Stable Housing Primary Care Clinicb |

1.55 (0.71–3.37) | 2.35** (1.24–4.47) | 2.18 (0.89–5.30) |

| Insuranceb | 0.84 (0.36–1.93) | 0.98 (0.49–1.99) | 0.97 (0.35–2.67) |

P<0.05,

P<0.01,

P<0.001

Continuous variable, in years

Binary variable

Continuous variable with value 0–2

History of use three times per week or greater, initiated prior to the end of the target year

Experienced symptoms at any time prior to the end of the target year

ARR (exponentiated multinomial log odds) adjusted for all other variables in the table

Cohabitors spent the majority of days staying with friends or family

Unsheltered cluster spent the majority of days unsheltered (on the street or other place not ordinarily used as sleeping accommodations)

Multiple Institution Users spent the majority of days in shelters, jail, transitional housing, and other institutions

Renters spent the majority of days in rented rooms or apartments

DISCUSSION

Within this population-based sample of older homeless people in Oakland, California, four distinct residential patterns emerged, which were associated with duration since last period of stable housing, gender, and social supports prior to losing stable housing.

Although most homeless research is based on individuals sampled from shelters or unsheltered environments, a large proportion of individuals experiencing homelessness stay temporarily with friends or family and share many of the vulnerabilities as other homeless populations, but may be undersampled (Crawley et al., 2013; Gaetz; et al., 2013). Drawing samples only from homeless shelters is problematic because the median shelter stay for a single adult is just over two weeks (US Department of Housing and Urban Development, 2011). We found only a minority of participants utilized homeless shelters for more than a few days. This may be due in part to the fact that despite increasing rental costs, Oakland has a limited availability of shelter beds. Although the proportion of unsheltered homeless individuals in Oakland has remained about half of homeless individuals, over the past decade there has been a relative decrease in shelter capacity with concomitant efforts to increase permanent supportive housing stock ("Alameda Countywide Homeless Count and Survey 2013. Summary Findings & Policy Implicatons.," 2013). Studies that have sampled homeless individuals from a broader array of places (Burnam & Koegel, 1988; Curtis et al., 2013; Morrison, 2009) have not characterized the venues in which participants reside (van Laere et al., 2009). The current study provides a comprehensive perspective of homelessness in an older adult population by including recruiting venues through which homeless people transition. Because Oakland has a higher proportion of African-Americans than the country as a whole, our sample has a larger proportion of African-Americans (Dietz, 2007; Hahn et al., 2006; Kushel et al., 2002), although the relative proportions (3–4 times the general population of the region) are similar. Similar to other studies of older homeless adults, we found a higher rate of chronic illness (Hahn et al., 2006), cognitive impairments (Buhrich et al., 2000; Fischer et al., 1986), and a lower rate of active illicit drug use than younger samples (Gelberg et al., 1990).

We found that the largest residential cluster was composed of those who were primarily unsheltered. These findings are consistent with national data showing that approximately half of single homeless adults in the United States are unsheltered (Henry et al., 2014; "Opening Doors: Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness Update 2013," 2014). This group is made up of both individuals who have experienced prolonged homelessness since early adulthood and those who became homeless in later life. Unsheltered individuals did not have differences in many factors in early life but did have higher rates of cocaine use when compared to the multiple institution users. Cocaine use may have made it difficult to stay in homeless shelters, as most have policies against active drug use. Unsheltered participants’ lack of social support may have led to difficulty finding a place to stay or reflect reluctance to stay in places that require frequent contact with others. These individuals may also lack institutional resources to prevent being unsheltered (Dunn & Hayes, 2000; Waldbrook, 2015).

The higher level of social support prior to the end of the target year for the multiple institution users may suggest that these ties played a role in preventing unsheltered time or may be indicative of an ability to navigate social relationships that are needed in institutional settings. Cycling between multiple institutions may be a survival strategy for those who are unstably housed but may create dependence on these institutions or prolong homelessness (DeVerteuil, 2003). Institutional cycling may also be a substitute for recently exhausted social support. The higher rates of jail days over the past six months among multiple institution users could be a result of jails discharging inmates to shelters (Metraux et al., 2010), or may be because those who stay in shelters may be more closely observed, and thus more likely to be incarcerated for infractions. The lifetime history of incarceration prior to losing stable housing amongst the multiple institution users was similar to the unsheltered group, and was common amongst the entire sample as seen in other samples of homeless adults (Greenberg & Rosenheck, 2008; Tsai et al., 2014). The causes of the high rates of incarceration are multifactorial. Criminal justice system involvement is an important risk factor for homelessness, both because of shared risk factors (mental health and substance use disorders, African-American race) (Carson, 2014; "Current Statistics on the Prevalence and Characteristics of People Experiencing Homelessness in the United States," 2011) and because having a criminal justice history creates barriers to employment and housing options and disruptions in social support (Greenberg & Rosenheck, 2008), all increasing homelessness. Homelessness may increase the risk of criminal justice system involvement (Greenberg & Rosenheck, 2008; Kushel et al., 2005).

We identified a group of homeless individuals who resided primarily with friends or family members in the prior six months, yet met the HEARTH definition of homelessness. The cohabiters cluster, who have also been described as ‘couchsurfers’ or ‘doubled-up’ (Ahrentzen, 2003; Wright et al., 1998), contained the highest proportion of women. These individuals exhibited the highest levels of social supports, which may have allowed them to avoid being unsheltered. In a study of homeless individuals with severe mental illness, women were more likely to employ the strategy of being doubled-up (Hopper et al., 1997). Women may have stronger social networks (Bassuk, 1993; Tucker et al., 2009) or may be more willing to accept help, with a lower degree of stigma about relying on social ties (Griffiths et al., 2011). Women may prefer to avoid emergency shelters and unsheltered environments because of the associated real or perceived threat of sexual, and economic exploitation and environmental risks (Lazarus et al., 2011; Waldbrook, 2015). However, women’s reliance on their social networks may pose different risks such as increasing their risk of exposure to sexual and financial exploitation by partners, family, or friends (Kushel et al., 2003; Maher et al., 1996; Riley et al., 2007). We found that prior to losing stable housing, the cohabiters cluster experienced significantly more abuse than unsheltered individuals, highlighting their vulnerability even when housed. Our data suggest that higher levels of social support are protective against being unsheltered, but aren’t sufficient to avoid homelessness. This cluster may represent a group of individuals who may benefit from rapid rehousing programs or housing vouchers in order to prevent the progression to chronic homelessness (Gubits et al., 2015; "Rapid Re-Housing: Creating Programs that Work," 2009).

As did DeVerteuil (DeVerteuil, 2003), we found a subset of participants with a recent onset of homelessness that recently resided in rental units. Members of this group lost their stable housing in the prior six months and have stayed in shelters or unsheltered environments since. This group had the lowest level of social supports in their last year of stable housing. These low levels may explain why they went to homeless shelters or unsheltered environments immediately after losing housing. Studies about homeless families suggest that some families with a ‘slow slide’ into homelessness will double-up with friends or family members prior to entering emergency shelters, while others may abruptly transition from rental apartments to shelters (Weitzman et al., 1990). Our cluster likely represents those without the social supports to delay the onset of homelessness.

Although the clusters described living environments, we also found temporal patterns in the data that differentiated the clusters. The nature of our cross-sectional sample allowed us to enroll people at different stages of their homelessness trajectory. While the majority of the cohabiters and renters had been homeless for less than six months, the unsheltered homeless and the multiple institution users had been homeless for significantly longer and may be similar to Kuhn and Culhane’s ‘chronically homeless’ typology (Kuhn & Culhane, 1998). We found a discrepancy between the duration of the current homeless episode and the duration since last stable housing for the cohabiters cluster; despite being homeless for a shorter period of time during this episode, the last period of stable housing for cohabiters was similar to that of the unsheltered and multiple institution users, suggesting more chronic housing instability with episodic “rehousing” by doubling up for short periods of time.

There are several limitations to our study. As this was a baseline study of a cohort, the data presented are cross-sectional and reliant on participant self-report of housing status and life history; recall of target year events in particular may have been subject to recall bias particularly for those whose last stable housing was longer ago. We may have been able to describe more subpopulations of the homeless – reducing heterogeneity within the multiple institution user cluster – although we found few meaningful differences with the addition of two clusters (see Supplementary Table). The patterns of homelessness we found may represent local trends; it is possible that certain groups may have been under or overrepresented, as it is difficult to know the true source population. Future research in different populations is needed to determine whether these residential clusters may be found more broadly in people experiencing homelessness.

Our environment-based approach adds to the existing literature on risks associated with homelessness. Homeless individuals have higher rates of morbidity than housed individuals. It is not known how much of this difference is attributed to the experience of homelessness itself versus the selection into homelessness of people with higher rates of pre-existing co-morbidities.

Further research on the newly homeless individuals and cohabiters in this cohort may elucidate more clearly the trajectories of these different phenotypes of homelessness. Developing a more nuanced understanding of the environments in which homeless people live may contribute to housing policies and epidemiologic modeling of the risks associated with unstable housing.

Supplementary Material

Residential Patterns in Older Homeless Adults: Results of a Cluster Analysis Highlights.

Older homeless adults live in distinct environments with different patterns of strengths and risks

We describe four clusters: unsheltered individuals, cohabiters, institution users, and renters who recently became homeless

Cohabiters are more likely to be women who have social supports but histories of abuse and episodes of unstable housing

Renters lack social supports and have become homeless at an older age

Social supports may play a role in protecting against being unsheltered

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by grants from the National Institute on Aging (NIA) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (K24AG046372 [Kushel], R01AG041860 [Ponath, Guzman, Riley]). These funding sources had no role in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

The authors gratefully acknowledge their colleagues Angela Allen, Pamela Olsen, Nina Fiellin, Tauni Marin, and Kenneth Perez for their invaluable contributions to the HOPE HOME study. The authors also thank the staff at St. Mary’s Center, and the HOPE HOME Community Advisory Board for their guidance and partnership.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Adlaf EM, Zdanowicz YM. A cluster-analytic study of substance problems and mental health among street youths. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1999;25:639–660. doi: 10.1081/ada-100101884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahrentzen S. Double Indemnity or Double Delight? The Health Consequences of Shared Housing and “Doubling Up”. Journal of Social Issues. 2003;59:547–568. [Google Scholar]

- Akaike H. Information Theory and an Extension of the Maximum Likelihood Principle. In: Parzen E, Tanabe K, Kitagawa G, editors. Selected Papers of Hirotugu Akaike. New York: Springer; 1998. pp. 199–213. [Google Scholar]

- Alameda Countywide Homeless Count and Survey 2013. Summary Findings & Policy Implicatons. Hayward, CA: EveryOne Home; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Barrow SM, Herman DB, Cordova P, Struening EL. Mortality among homeless shelter residents in New York City. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:529–534. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.4.529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassuk EL. Social and economic hardships of homeless and other poor women. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1993;63:340–347. doi: 10.1037/h0079443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RT, Kiely DK, Bharel M, Mitchell SL. Geriatric syndromes in older homeless adults. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:16–22. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1848-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning CR, Cagney KA. Moving beyond poverty: neighborhood structure, social processes, and health. J Health Soc Behav. 2003;44:552–571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brusco M, Köhn H-F. Exemplar-Based Clustering via Simulated Annealing. Psychometrika. 2009;74:457–475. [Google Scholar]

- Buhrich N, Hodder T, Teesson M. Prevalence of cognitive impairment among homeless people in inner Sydney. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51:520–521. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.51.4.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnam MA, Koegel P. Methodology for Obtaining a Representative Sample of Homeless Persons: The Los Angeles Skid Row Study. Evaluation Review. 1988;12:117–152. [Google Scholar]

- Burt MR United States. Interagency Council on the Homeless., & Urban Institute. Homelessness : programs and the people they serve : findings of the National Survey of Homeless Assistance Providers and Clients : summary. Washington, DC: U.S. Dept. of Housing and Urban Development; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Calinski T, Harabasz J. A dendrite method for cluster analysis. Communications in Statistics. 1974;3:1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Carson EA. Prisoners in 2013. Washington, D. C: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Crawley J, Kane D, Atkinson-Plato L, Hamilton M, Dobson K, Watson J. Needs of the hidden homeless - no longer hidden: a pilot study. Public Health. 2013;127:674–680. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2013.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culhane DP, Metraux S, Bainbridge J. The Age Structure of Contemporary Homelessness: Risk Period or Cohort Effect? Penn School of Social Policy and Practice Working Paper. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- Current Statistics on the Prevalence and Characteristics of People Experiencing Homelessness in the United States. Washington, D.C.: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis MA, Corman H, Noonan K, Reichman NE. Life shocks and homelessness. Demography. 2013;50:2227–2253. doi: 10.1007/s13524-013-0230-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danseco ER, Holden EW. Are There Different Types of Homeless Families? A Typology of Homeless Families Based On Cluster Analysis. Family Relations. 1998;47:159–165. [Google Scholar]

- DeVerteuil G. Homeless Mobility, Institutional Settings, and the New Poverty Management. Environment and Planning A. 2003;35:361–379. [Google Scholar]

- Dietz TL. Predictors of reported current and lifetime substance abuse problems among a national sample of U.S. homeless. Subst Use Misuse. 2007;42:1745–1766. doi: 10.1080/10826080701212360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn JR, Hayes MV. Social inequality, population health, and housing: a study of two Vancouver neighborhoods. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51:563–587. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00496-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everitt BS, Landau S, Leese M, Stahl D. Cluster Analysis. Chichester, United Kingdom: Wiley; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Farrow JA, Deisher RW, Brown R, Kulig JW, Kipke MD. Health and health needs of homeless and runaway youth. A position paper of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. J Adolesc Health. 1992;13:717–726. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(92)90070-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazel S, Geddes JR, Kushel M. The health of homeless people in high-income countries: descriptive epidemiology, health consequences, and clinical and policy recommendations. Lancet. 2014;384:1529–1540. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61132-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer PJ, Shapiro S, Breakey WR, Anthony JC, Kramer M. Mental health and social characteristics of the homeless: a survey of mission users. Am J Public Health. 1986;76:519–524. doi: 10.2105/ajph.76.5.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaetz S, Donaldson J, Richter T, Gulliver T. The State of Homelessness in Canada 2013. Toronto, Canada: Canadian Alliance to End Homelessness; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Garibaldi B, Conde-Martel A, O'Toole TP. Self-reported comorbidities, perceived needs, and sources for usual care for older and younger homeless adults. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:726–730. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0142.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelberg L, Linn LS, Mayer-Oakes SA. Differences in health status between older and younger homeless adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1990;38:1220–1229. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1990.tb01503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gielen AC, O'Campo PJ, Faden RR, Kass NE, Xue X. Interpersonal conflict and physical violence during the childbearing year. Soc Sci Med. 1994;39:781–787. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90039-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg GA, Rosenheck RA. Jail incarceration, homelessness, and mental health: a national study. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59:170–177. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.2.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths KM, Crisp DA, Jorm AF, Christensen H. Does stigma predict a belief in dealing with depression alone? J Affect Disord. 2011;132:413–417. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubits D, Shinn M, Bell S, Wood M, Dastrup S, Solari CD, et al. Family Options Study Short-Term Impacts of Housing and Services Interventions for Homeless Families. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn JA, Kushel MB, Bangsberg DR, Riley E, Moss AR. BRIEF REPORT: the aging of the homeless population: fourteen-year trends in San Francisco. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:775–778. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00493.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hair JF, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE. Multivariate Data Analysis. New York: Macmillan USA; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen L, Penko J, Guzman D, Bangsberg DR, Miaskowski C, Kushel MB. Aberrant behaviors with prescription opioids and problem drug use history in a community-based cohort of HIV-infected individuals. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;42:893–902. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry M, Cortes; A, Shivji A, Buck K. The 2014 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress. Washington, D.C.: U.S Department of Housing and Urban Development; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hibbs JR, Benner L, Klugman L, Spencer R, Macchia I, Mellinger A, et al. Mortality in a cohort of homeless adults in Philadelphia. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:304–309. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199408043310506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homeless Emergency Assistance and Rapid Transition to Housing Act of 2009. Definition of homelessness. U.S. Congress; 2009. P.L. 111–22, Sec. 1003. [Google Scholar]

- Hopper K, Jost J, Hay T, Welber S, Haugland G. Homelessness, severe mental illness, and the institutional circuit. Psychiatr Serv. 1997;48:659–665. doi: 10.1176/ps.48.5.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huntington N, Buckner JC, Bassuk EL. Adaptation in Homeless Children: An Empirical Examination Using Cluster Analysis. American Behavioral Scientist. 2008;51:737–755. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang SW. Homelessness and health. CMAJ. 2001;164:229–233. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang SW, Wilkins R, Tjepkema M, O'Campo PJ, Dunn JR. Mortality among residents of shelters, rooming houses, and hotels in Canada: 11 year follow-up study. BMJ. 2009;339:b4036. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b4036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahiel R, Babor TF. Characteristics and dynamics of homeless families with children: Final report to the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2011. Toward a typology of homeless families: Conceptual and methodological issues. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman L, Rousseeuw PJ. Finding Groups in Data: An Introduction to Cluster Analysis. New York: Wiley-Interscience; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Kohn HF, Steinley D, Brusco MJ. The p-median model as a tool for clustering psychological data. Psychol Methods. 2010;15:87–95. doi: 10.1037/a0018535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruskal WH, Wallis WA. Use of Ranks in One-Criterion Variance Analysis. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1952;47:583–621. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn R, Culhane DP. Applying cluster analysis to test a typology of homelessness by pattern of shelter utilization: results from the analysis of administrative data. Am J Community Psychol. 1998;26:207–232. doi: 10.1023/a:1022176402357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushel MB. Older homeless adults: can we do more? J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:5–6. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1925-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushel MB, Evans JL, Perry S, Robertson MJ, Moss AR. No door to lock: victimization among homeless and marginally housed persons. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2492–2499. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.20.2492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushel MB, Hahn JA, Evans JL, Bangsberg DR, Moss AR. Revolving doors: imprisonment among the homeless and marginally housed population. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:1747–1752. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.065094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushel MB, Perry S, Bangsberg D, Clark R, Moss AR. Emergency department use among the homeless and marginally housed: results from a community-based study. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:778–784. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.5.778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan TY, Wu SC, Chang WC, Chen CY. Home environmental problems and physical function in Taiwanese older adults. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2009;49:335–338. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2008.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus L, Chettiar J, Deering K, Nabess R, Shannon K. Risky health environments: women sex workers' struggles to find safe, secure and non-exploitative housing in Canada's poorest postal code. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73:1600–1607. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher L, Dunlap E, Johnson BD, Hamid A. Gender, Power, and Alternative Living Arrangements in the Inner-City Crack Culture. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 1996;33:181–205. [Google Scholar]

- Marr MD, DeVerteuil G, Snow D. Towards a contextual approach to the place- homeless survival nexus: An exploratory case study of Los Angeles County. Cities. 2009;26:307–317. [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, Peters R, Smith I, Grissom G, et al. The Fifth Edition of the Addiction Severity Index. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1992;9:199–213. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(92)90062-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metraux S, Byrne T, Culhane DP. Institutional discharges and subsequent shelter use among unaccompanied adults in New York City. Journal of Community Psychology. 2010;38:28–38. [Google Scholar]

- Metraux S, Eng N, Bainbridge J, Culhane DP. The impact of shelter use and housing placement on mortality hazard for unaccompanied adults and adults in family households entering New York City shelters: 1990–2002. J Urban Health. 2011;88:1091–1104. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9602-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison DS. Homelessness as an independent risk factor for mortality: results from a retrospective cohort study. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38:877–883. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Flaherty B. Individual homelessness: Entries, exits, and policy. Journal of Housing Economics. 2012;21:71–100. [Google Scholar]

- Opening Doors: Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness Update 2013. Washington, D.C.: United States Interagency Council on Homelessness; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Palar K, Kushel M, Frongillo EA, Riley ED, Grede N, Bangsberg D, et al. Food Insecurity is Longitudinally Associated with Depressive Symptoms Among Homeless and Marginally-Housed Individuals Living with HIV. AIDS and Behavior. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0922-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapid Re-Housing. Creating Programs that Work. Washington, DC: The National Alliance to End Homelessness; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Riley ED, Weiser SD, Sorensen JL, Dilworth S, Cohen J, Neilands TB. Housing patterns and correlates of homelessness differ by gender among individuals using San Francisco free food programs. J Urban Health. 2007;84:415–422. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9153-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel LJ, Glass TA, Thorpe RJ, Jr, Szanton SL, Roth DL. Household and neighborhood conditions partially account for associations between education and physical capacity in the National Health and Aging Trends Study. Soc Sci Med. 2015;128:67–75. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinn M, Gottlieb J, Wett JL, Bahl A, Cohen A, Baron Ellis D. Predictors of homelessness among older adults in New York city: disability, economic, human and social capital and stressful events. J Health Psychol. 2007;12:696–708. doi: 10.1177/1359105307080581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 11. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai J, Rosenheck RA, Kasprow WJ, McGuire JF. Homelessness in a national sample of incarcerated veterans in state and federal prisons. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2014;41:360–367. doi: 10.1007/s10488-013-0483-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsemberis S, McHugo G, Williams V, Hanrahan P, Stefancic A. Measuring homelessness and residential stability: The residential time-line follow-back inventory. Journal of Community Psychology. 2007;35:29–42. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JS, Kennedy D, Ryan G, Wenzel SL, Golinelli D, Zazzali J. Homeless Women's Personal Networks: Implications for Understanding Risk Behavior. Hum Organ. 2009;68:129–140. doi: 10.17730/humo.68.2.m23375u1kn033518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Housing and Urban Development. The 2010 Annual Homeless Assessment Report to Congress. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- van Laere IR, de Wit MA, Klazinga NS. Pathways into homelessness: recently homeless adults problems and service use before and after becoming homeless in Amsterdam. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbrugge LM, Jette AM. The disablement process. Soc Sci Med. 1994;38:1–14. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90294-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijayaraghavan M, Penko J, Bangsberg DR, Miaskowski C, Kushel MB. Opioid analgesic misuse in a community-based cohort of HIV-infected indigent adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2013a;173:235–237. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijayaraghavan M, Penko J, Vittinghoff E, Bangsberg D, Miaskowski C, Kushel M. Smoking Behaviors in a Community-Based Cohort of HIV-Infected Indigent Adults. AIDS and Behavior. 2013b:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0576-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogenthaler NS, Kushel MB, Hadley C, Frongillo EA, Jr, Riley ED, Bangsberg DR, et al. Food insecurity and risky sexual behaviors among homeless and marginally housed HIV-infected individuals in San Francisco. AIDS and Behavior. 2013;17:1688–1693. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0355-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldbrook N. Exploring opportunities for healthy aging among older persons with a history of homelessness in Toronto, Canada. Soc Sci Med. 2015;128:126–133. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward JH. Hierarchical Grouping to Optimize an Objective Function. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1963;58:236–244. [Google Scholar]

- Weiser SD, Frongillo EA, Ragland K, Hogg RS, Riley ED, Bangsberg DR. Food insecurity is associated with incomplete HIV RNA suppression among homeless and marginally housed HIV-infected individuals in San Francisco. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:14–20. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0824-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiser SD, Hatcher A, Frongillo EA, Guzman D, Riley ED, Bangsberg DR, et al. Food insecurity is associated with greater acute care utilization among HIV-infected homeless and marginally housed individuals in San Francisco. J Gen Intern Med. 2013a;28:91–98. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2176-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiser SD, Yuan C, Guzman D, Frongillo EA, Riley ED, Bangsberg DR, et al. Food insecurity and HIV clinical outcomes in a longitudinal study of urban homeless and marginally housed HIV-infected individuals. Aids. 2013b;27:2953–2958. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000432538.70088.a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitzman BC, Knickman JR, Shinn M. Pathways to Homelessness Among New York City Families. Journal of Social Issues. 1990;46:125–140. [Google Scholar]

- Wolch JR, Dear M, Akita A. Explaining Homelessness. Journal of the American Planning Association. 1988;54:443–453. [Google Scholar]

- Wright BRE, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Silva PA. Factors Associated with Doubled-Up Housing-- A Common Precursor to Homelessness. Social Service Review. 1998;72:92–111. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.