Abstract

Objective

Research indicates that foster parents often do not receive sufficient training and support to help them meet the demands of caring for foster children with emotional and behavioral disturbances. Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT) is a clinically efficacious intervention for child externalizing problems, and it also has been shown to mitigate parenting stress and enhance parenting attitudes and behaviors. However, PCIT is seldom available to foster families, and it rarely has been tested under intervention conditions that are generalizable to community-based child welfare service contexts. To address this gap, PCIT was adapted and implemented in a field experiment using 2 novel approaches—group-based training and telephone consultation—both of which have the potential to be integrated into usual care.

Method

This study analyzes 129 foster-parent-child dyads who were randomly assigned to 1 of 3 conditions: (a) waitlist control, (b) brief PCIT, and (c) extended PCIT. Self-report and observational data were gathered at multiple time points up to 14 weeks post baseline.

Results

Findings from mixed-model, repeated measures analyses indicated that the brief and extended PCIT interventions were associated with a significant decrease in self-reported parenting stress. Results from mixed-effects generalized linear models showed that the interventions also led to significant improvements in observed indicators of positive and negative parenting. The brief course of PCIT was as efficacious as the extended PCIT intervention.

Conclusions

The findings suggest that usual training and support services can be improved upon by introducing foster parents to experiential, interactive PCIT training.

Keywords: foster care, parent training, intervention, parent-child interaction therapy, stress, parenting

Children often enter foster care with emotional and behavioral disturbances (Clausen, Landsverk, Ganger, Chadwick, & Litrownik, 1998; Keil & Price, 2006), which present foster parents with caregiving demands that they might not be adequately trained to meet. These conditions are especially concerning given the limited availability of empirically supported mental health assessment and treatment services for foster children (Burns et al., 2004; Horwitz et al., 2012). Whereas the mental health challenges of foster children have garnered considerable scholarly attention, less is known about foster parents and their caregiving capacities. Available evidence has shown that foster parents often perceive that they do not receive the extent of support they need from the child welfare system to manage the challenges of caring for children with special mental health needs (Denby, Rindfleisch, & Bean, 1999; MacGregor, Rodger, Cummings, & Leschied, 2006). Foster parents have frequently reported experiencing high levels of caregiving burden and parenting stress as well (Jones & Morrisette, 1999; Murray, Tarren-Sweeney, & France, 2011; Vanschoonlandt, Vanderfaeillie, Van Holen, De Maeyer, & Robberechts, 2013). Prevailing theory and evidence suggests that caregiving stress as well as a lack of social support undermines parenting efficacy (Abidin, 1992; Healey, Flory, Miller, & Halperin, 2011; Ponnet et al., 2013).

Considering their elevated levels of caregiving burden and parenting stress, it is not surprising that some foster caregivers find it difficult to provide an adequate caregiving environment. Based on their review of the literature, Orme and Buehler (2001) concluded that approximately 15% of foster parents exhibited “poor or troubled parenting” (p. 7). More recent studies have also shown that a sizeable minority of foster parents do not provide foster children with appropriate care (Barth et al., 2008; Linares, Montalto, Li, & Oza, 2006; Vanderfaeillie, Van Holen, Trogh, & Andries, 2012). Another concern is that capable providers might decide to relinquish custody of their foster children due to the stress associated with caring for dysregulated children without requisite training and support. Research has demonstrated that placement disruptions occur more frequently among children with emotional and behavioral problems, and that placement disruptions contribute to or exacerbate children’s emotional and behavioral problems (Barth et al., 2007; Newton, Litrownik, & Landsverk, 2000; Oosterman, Schuengel, Wim Slot, Bullens, & Doreleijers, 2007).

In light of their need for specialized parenting skills, it is unsurprising that foster parents often request training in behavior management techniques (Murray et al., 2011). However, the training foster parents typically receive lacks scientific validation at best, and at worst it appears to be ineffective (Berry, 1988; Dorsey et al., 2008). For example, one study of a widely-used curriculum—Model Approach to Partnerships in Parenting Group Preparation and Selection of Foster and/or Adoptive Families (i.e., MAPP/GPS)—revealed that foster parents who completed training were no better equipped to manage child behavior problems than were foster parents who had not completed training (Puddy & Jackson, 2003). These results reinforced those of an evaluation by Lee and Holland (1991), who reported that an earlier version of this curriculum did not lead to expected changes in foster parent empathy, use of physical punishment, or knowledge of child development. Another commonly used training curriculum, Foster Parent Resources for Information, Development, and Education (i.e., PRIDE), has yet to be rigorously tested (Dorsey et al., 2008). Thus, despite the need for foster parents to develop effective behavior management skills, there is scant evidence that the training they receive actually promotes these competencies.

When foster parents do receive validated parent training interventions they often show improvements in managing difficult child behaviors and parenting stress. For example, the Multidimensional Treatment Foster Care for Preschoolers (MTFC-P) program, which provides child, parent, and family services for up to 12 months, has been linked to reduced levels of caregiver stress and improved permanency outcomes (Fisher, Kim, & Pears, 2009; Fisher & Stoolmiller, 2008). The Incredible Years® is another comprehensive, multimodal intervention that has been successfully adapted for the child welfare service sector (Webster-Stratton & Reid, 2010). The Incredible Years typically incorporates parent, child, and teacher curricula, and calls for at least 18 two-hour sessions plus support and consultation, yet one study demonstrated that a 12-session model was associated with enhanced foster parenting (Linares et al., 2006). Modifications in dosage (i.e., duration) along these lines might help child welfare agencies adopt models such as MTFC-P and The Incredible Years by reducing costs and decreasing the extent to which agency services and resources have to be reconfigured.

A third evidence-based parent training intervention, Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT), has a more circumscribed treatment focus and service array than does the MTFC-P and Incredible Years programs. As a result, PCIT can be more readily assimilated into existing systems of care. Designed for children between 2 and 7 years old who have behavior problems, PCIT is usually provided over 12 to 20 weekly sessions by a therapist who helps caregivers develop specific parenting skills through psychoeducation, coaching, modeling, and role-play. The defining characteristics of PCIT include (a) joint treatment for parent and child, (b) in vivo parent coaching, (c) use of assessment to guide treatment, and (d) tailoring of treatment to the child’s developmental level and caregiver’s level of mastery (McNeil & Hembree-Kigin, 2010).

According to observational and self-report data, and as compared with wait list controls, PCIT has been found to produce large effect size changes in child and parent behaviors (for review, see Thomas & Zimmer-Gembeck, 2007). Participation in PCIT has been linked to significant reductions in caregiver stress, child abuse potential, and physical abuse recurrence, gains in positive parenting parent attitudes and behaviors, and improvements in parent-child interactions (Cooley, Veldorale-Griffin, Petren, & Mullis, 2014; Thomas & Zimmer-Gembeck, 2007). These findings have been replicated with child welfare samples (Chaffin et al., 2004; Timmer, Zebell, Culver, & Urquiza, 2010), including foster parents (Timmer, Urquiza, & Zebell, 2006).

Despite its circumscribed focus and clinical efficacy, there are barriers to integrating PCIT into routine care for foster families. Many regions of the United States face a shortage of child mental health therapists (Burns et al., 2004), and most of these therapists have not been trained in PCIT. In addition, the uptake of PCIT might be slowed by the initial investments required for clinical training as well as the changes the model requires in child welfare staffing and service realignment. Moreover, when compared to the cost of usual care, the cost of a treatment that lasts up to 20 sessions might be a disincentive because a large proportion of foster children between the ages of 2 and 7 years have mental health disturbances that would qualify them for PCIT. Finally, similar to many clinical treatments, standard PCIT programs tend to have high rates of attrition (Fernandez & Eyberg, 2009; Werba, Eyberg, Boggs, & Algina, 2006). Some foster parents, particularly those who face high caregiving and employment demands, might be unwilling to commit to a lengthy course of treatment.

To address these barriers, we conducted a randomized trial of an adaptation of PCIT designed to (a) help foster parents access empirically supported behavior management training, and (b) help foster children access empirically supported mental health services. As described below (see Interventions), we replaced the conventional PCIT format with two novel approaches: group training and telephone consultation. Foster parents typically receive training in a group setting, and child welfare professionals often communicate with clients by phone. Thus, both service modalities have the potential to be implemented efficiently and integrated seamlessly into usual care. Research has revealed that parent training programs can be delivered efficaciously as group-based interventions (Ruma, Burke, & Thompson, 1996), and a small pilot study also demonstrated the feasibility of implementing PCIT with foster parents in a group setting (McNeil, Herschell, Gurwitch, & Clemens-Mowrer, 2005). In addition, phone consultation has been shown to generate benefits for clients (Leach & Christensen, 2006), including families receiving PCIT (Nixon, Sweeney, Erickson, & Touyz, 2004).

Eligible foster children residing in licensed, nonrelative foster care homes were randomly assigned to 1 of 3 conditions: (a) waitlist control, (b) brief PCIT, (c) extended PCIT. This study expands our previous results that indicated both the brief and extended models of PCIT were associated with a significant reduction in child externalizing and internalizing symptoms (Mersky, Topitzes, Grant-Savela, Brondino, & McNeil, 2014). In the present study, we assessed intervention impacts on indicators of parenting stress and behavior, guided by three research questions:

Research Question 1

Compared with a waitlist control group of foster parents receiving usual services, do foster parents who are randomly assigned to receive PCIT report significantly reduced levels of parenting stress?

Research Question 2

Compared with controls, do observational data show that foster parents who receive PCIT significantly increase their positive parenting behaviors and significantly decrease their negative parenting behaviors?

Research Question 3

Compared with foster parents who receive a brief course of PCIT, do foster parents who receive an extended course of PCIT show a significantly greater increase in positive parenting behaviors and greater decrease in negative parenting behaviors and stress?

Method

Participants

Participants were 129 foster parent-child dyads from a large metropolitan area in the U.S. Midwest. Using child welfare case records housed in the State Automated Child Welfare Information System, the research team selected foster children as potential participants if they were between the 2.5 and 7 years old, and their current placement was in a licensed, nonrelative foster home. Referrals of potential participants were also accepted from child welfare case managers and other service professionals who learned about the program. Children with intellectual, physical, or pervasive developmental disabilities (e.g., autism, deafness) according to child welfare case records were excluded from the study. To minimize predictable treatment attrition, children were excluded if case records or consultation with agency personnel revealed that family reunification or another change of placement was imminent.

Foster parents of children who met these inclusionary and exclusionary criteria were recruited to participate in the study with their child. During an initial recruitment call, foster parents who expressed interest in the study were screened using the Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory (Eyberg & Pincus, 1999) that produces two scores: an intensity score, which assesses the frequency with which the child exhibits the problem behaviors; and a problem score, which indicates parent tolerance and distress associated with the behaviors. The child was eligible for the study if his or her foster parent’s score on the Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory was in the clinical range. If two or more eligible foster children resided in the same home, one child was selected by the foster parent to participate in the intervention to minimize treatment burden and maintain equivalence among caregivers. Similarly, families with more than one foster parent in the home were asked to select a focal adult who would participate in the PCIT trainings. None of the children or caregivers had received PCIT prior to enrollment. Per state regulations, all foster parents in the treatment and control conditions had completed 30 hours of preservice training before becoming a licensed foster parent, and they were required to attend 10 hours of in-service training per year to maintain their licensure.

The study sample was predominantly racial/ethnic minority children (e.g., 61% African American, 18% Hispanic). Sample children averaged 4.6 years of age at enrollment, and 56% were girls. Nearly half (49%) of foster parents were non-Hispanic Caucasian, 45% were African American, and 5% were Hispanic. The mean age of foster parents was 44 years, and 89% were women. More than half (52%) of foster parents were married, and 94% had at least a high school diploma or equivalency test credential. The median duration of foster parenting experience was 24 months, and 72% of foster parents were caring for multiple foster children.

Procedure

After study procedures were approved by a university institutional review board, the research staff initiated recruitment activities. Foster parent-child dyads were recruited and enrolled in waves (i.e., cohorts) according to a predetermined PCIT training schedule. For each cohort, participants were randomly assigned to either the waitlist control condition or to 1 of 2 treatment conditions. This staggered approach minimized the time lapse between study recruitment and the start of active participation and helped to maintain the desired staff-client ratio in the PCIT training groups. During recruitment phone calls initiated by the research team, 186 foster parents completed an oral consent procedure, and were then screened with the Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory. A total of 18 foster families were deemed ineligible because the foster parents’ scores were not in the clinical range on the Inventory’s intensity or problem scales. Of those families who were eligible for study participation, eight foster parents declined to participate during the initial recruitment call, and an additional 31 eligible families opted out of study participation after they had completed the initial screening but before being randomly assigned to a study group.

A covariate-adaptive randomization procedure (i.e., minimization) was used to assign participants to 1 of 3 study conditions (i.e., waitlist control, brief PCIT, or extended PCIT). Minimization reduces the likelihood that allocations will differ by chance on factors hypothesized to impact outcomes (Pocock & Simon, 1975). For this study, the balancing factors included child age, gender, race/ethnicity, and foster parent race/ethnicity. The remaining 129 families received a letter informing them of their assignment to one of three study conditions, and then the foster parents provided written consent for the foster parent-child dyad. Of these, 15 foster parent-child dyads dropped out prior to their baseline assessment. Out of the 114 foster parent-child dyads that presented for a baseline assessment, 99 also completed an assessment at 8 weeks post baseline (76.2%) and 96 completed an assessment at 14 weeks post baseline (73.8%). Attrition rates did not differ significantly among study groups at the 14-week time point (F test, p = .861). Most instances of post-assignment drop out were due to client cancellation or no show (n = 24). Another 10 drop outs resulted from a change in the child’s placement; it was not possible to gather additional assessment data for these cases because all assessments relied on the original foster parent’s ratings of the child’s behavior and observations of the foster parent’s interactions with the child.

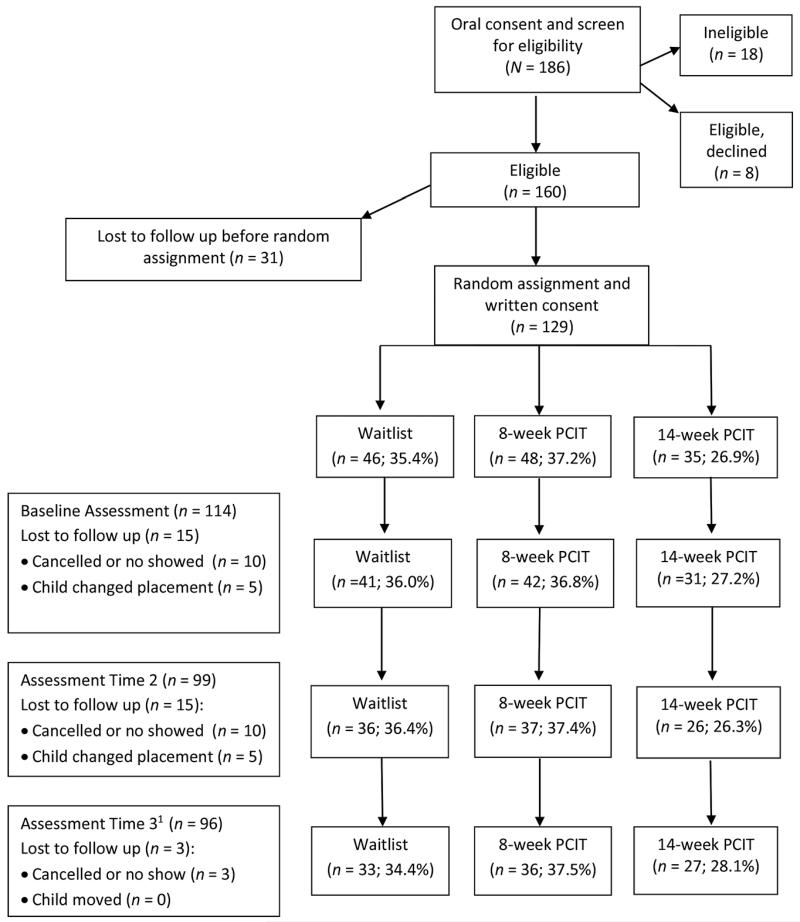

Children and foster parents in the treatment and control groups continued to receive usual services as designated by their case plan, including ongoing foster parent training, case management, and other psychosocial or pharmacological interventions. After their 14-week final assessment, control families were eligible to attend PCIT workshops. Due to resource constraints, the study included one less extended PCIT cohort than brief PCIT cohort, resulting in an imbalanced allocation between treatment groups. A CONSORT diagram depicting the flow of recruitment, enrollment, and randomization in the study is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Enrollment, randomization, and attrition flow chart for the field experiment of Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT) delivered as a brief (8-week) program and as an extended 14-week program, as compared with waitlist controls. Note. 1 Five participants who completed Time 3 assessments did not complete Time 2 assessments.

Assessments

Study data were derived from participant assessments and agency records maintained in a state-administered database. Foster parent-child dyads in all three study conditions presented to a university laboratory for a baseline assessment consisting of parent self-report measures and an observational protocol to record foster parent-child interactions. Foster parents were asked to fill out the same self-report measures by mail at 8 weeks post baseline; at 14 weeks post baseline, foster parent-child dyads returned to the laboratory to complete the self-report and observational assessments. Foster parents received modest compensation (i.e., $10 to $20) for time and travel associated with the assessment procedures.

Demographic questionnaire

A foster parent questionnaire was developed to gather household demographic information. These data were validated and, if missing, supplemented with data extracted from child welfare records. Characteristics recorded included age, gender, and race/ethnicity of foster parent and child, foster parent marital status, and the number of children in the home. Foster parent education was recorded on a scale from less than high school degree or equivalency test credential (coded 1) to some postgraduate college coursework (coded 5). The variable foster parent experience indicated the number of months each adult participant had been a licensed foster parent.

Parenting Stress Index Short Form

The Parenting Stress Index-Short Form (PSI-SF; Abidin, 1995) consists of 36 items that use a 5-point Likert response scale to produce a total stress score (range of 36 to 180 points), with scores of 90 and greater defined as clinically significant. The PSI-SF comprises three 12-item subscales: parental distress, parent—child dysfunctional interaction, and difficult child. The parental distress subscale measures perceptions of stressors associated with the role of being a parent, such as restrictions on daily life, household conflict, and lack of social support. The parent—child dysfunctional interaction subscale assesses the extent to which the parent perceives that the child is not meeting the parent’s expectations or that interactions with the child are unsatisfying. The difficult child subscale measures the extent to which the parent perceives the child’s behaviors as being difficult to manage. Studies of diverse samples have demonstrated that the PSI-SF demonstrates good internal consistency reliability and concurrent validity (Abidin, 1995; Haskett, Ahern, Ward, & Allaire, 2006; Hutcheson & Black, 1996). In the present study, internal consistency coefficients ranged from very good to excellent at all three assessment points for the Total Stress scale (α = .91—.93) as well as the three subscales for parental distress (α = .83—.89), parent—child dysfunctional interaction (α = .81—.87), and difficult child (α = .89—.90). Missing values within PSI-SF subscales were imputed using an expectation maximization approach, in which data from the subscale were entered as predictors and participant demographic characteristics were used as covariates. Missing value rates ranged from 0 to 5.1% across the three assessment time points.

Dyadic Parent–Child Interaction Coding System

The Dyadic Parent—Child Interaction Coding System (DPICS-II; Eyberg, Nelson, Duke, & Boggs, 2005) is an observational coding system used to assess behaviors and verbalizations of parents and children along with parent-child interactions. Studies have shown that the DPICS-II has sound internal consistency and discriminant validity, and that the measure is sensitive to effects associated with parent training interventions (Eyberg et al., 2005; Schuhmann, Foote, Eyberg, Boggs, & Algina, 1998). Foster parent-child dyads engaged in a 15 to 20 minute structured protocol that began with child-directed play, followed by parent-directed play, and then clean-up activities during which the child was asked to help pick up the play materials. Videotaped recordings of the sessions were coded at a different university by trained graduate and undergraduate students who were blind to the participants’ study condition. All coders were trained to 80% or greater interrater agreement prior to study involvement (McNeil & Hembree-Kigin, 2010). The present study uses codes that assess parent verbal and nonverbal behaviors, which were used to create four summative measures: (a) labeled praise across child-led play, parent-led play, and clean-up; (b) negative talk across child-led play parent-led play and clean-up; (c) positive composite of labeled praise, reflections, and behavior descriptions in child-led play; and (d) negative composite of negative talk and questions commands in child-led play.

Interventions

For the present study, PCIT was adapted so that the model would align with the format and setting of foster parent trainings as they are typically delivered. Foster parents assigned to one of the treatment conditions were asked to attend group PCIT trainings with six to eight families at a large, urban child welfare agency. Foster parents and foster children attended the PCIT trainings together, which introduced opportunities for in vivo coaching, skills application, and parent-child interaction. Foster parents also received periodic telephone consultation at home from their clinicians to reinforce knowledge and skills developed during workshops and homework activities. Foster parents received compensation ($50 to $90) for transportation costs and completing the PCIT trainings. In addition, participation in PCIT training was credited toward the annual training hours these parents are asked to fulfill as licensed foster care providers.

Brief PCIT

Foster parent-child dyads assigned to the brief PCIT group were asked to attend 2 full-day workshops, totaling 14 hours of training. The first day of training focused on child-directed interaction (CDI), the first of two PCIT phases, and the second day of training focused on parent-directed interaction (PDI), the second phase of PCIT. At the beginning of the first day, foster parents received 90 minutes of clinical instruction in CDI. Meanwhile, their children engaged in structured play in a separate child care area. A schedule of activities for the child care room was developed by a master’s-trained early education specialist who helped enlist and train undergraduate students in the study’s child care protocols.

After the initial instructional period, foster parents and children were re-united to practice CDI skills in a group setting. Stations equipped with different kinds of play materials were distributed throughout the room, and a foster parent-child dyad was positioned at each station. Two PCIT-trained graduate students circulated around the room to facilitate parent-child interactions through positive reinforcement, coaching, and role-plays. These activities prepared the parents and children for sessions with a PCIT therapist, which were conducted in a separate clinical setting in the same facility. Following a prearranged rotational system and standard PCIT protocols, each foster parent-child dyad was directed to a private training room to engage in a 20-minute CDI session with the therapist. The clinical room was equipped with a one-way mirror, which allowed the lead clinician to discreetly observe each dyad from an adjacent room. The observation room also featured conventional PCIT audiovisual equipment such as bug-in-ear communication devices that were used to communicate privately with the parent and a video camera that was used to record the proceedings. Videotaped sessions were used to enhance clinician training and fidelity to the model.

One important modification was made to the clinical protocol to maximize the benefits of the group-based model. With the aim of promoting therapeutic gains via observational learning, one foster parent who was not related to the parent-child dyad in the clinical room joined the clinician to observe the CDI of the parent-child dyad. After the session, this observing parent reunified with her or his child in the clinical training room and engaged in CDI while the outgoing parent joined the clinician to observe the session through the one-way mirror. This process was repeated until all families completed the CDI sessions. At the end of the training day, children returned to the child care room while parents and clinical staff held a group discussion to consolidate learning and create a homework plan involving 5 minutes of daily CDI practice.

The second training day, which was held 2 weeks after the first training day, mirrored the structure of the first but focused on PDI. Building on CDI knowledge and skills, PDI helps parents learn to manage difficult child behaviors through the use of adaptive verbal and nonverbal disciplinary practices. After a series of group-based and individualized PDI training sessions, the day closed with a group discussion. In addition to encapsulating lessons learned throughout the 2 days of training, this closing session was used to establish protocols and schedules for periodic telephone consultation and ongoing homework activities.

Foster parents in the brief PCIT group were asked to complete a 5-minute homework protocol each day, and to receive brief phone consultation each week for 4 weeks and every other week for another 4 weeks. The 15 to 20 minute consultations were used to refresh parents’ knowledge of and fidelity to PCIT, monitor and review progress, troubleshoot when children or parents were not making expected gains, and plan for future activities. Out of a maximum possible number of six consultations, the brief PCIT group had a mean of 4.4 phone consultations per participant. Similar to conventional PCIT, homework was used to bolster clinical gains, promote overlearning and mastery until behaviors become rote, and to ensure PCIT skills were applied in the home. The brief PCIT condition concluded after 8 weeks of phone consultation and homework.

Extended PCIT

Parent-child dyads in the extended PCIT group received the same initial treatment regimen as the brief PCIT group, consisting of 2 full-day trainings and 8 weeks of phone consultation and homework. Whereas services ceased at the 8-week point for the brief PCIT group, families in the extended PCIT group were asked to return to the same child welfare agency for another full day of PCIT training. This 7-hour booster session, which largely replicated the structure of the first two training days, focused primarily on promoting PDI skills because these skills are often more difficult to master than CDI skills. After the training session, the extended PCIT group was scheduled to receive 4 more phone consultation sessions along with regular homework activities over a 6-week period. Out of a maximum possible of 10 phone consultations, the extended PCIT group had a mean of 6.3 consultations per participant. The extended PCIT condition received 3 days of group training and 14 weeks of home-based intervention. Dosage effects can be estimated because both treatment groups received the same services but for different durations.

Table 1 displays descriptive comparisons of foster children and foster parent by study condition. Analyses were performed using chi-square tests for dichotomous variables and F tests for non-dichotomous variables. Omnibus tests indicated that the distributions of foster children in the three study groups did not differ significantly in child age, sex, or race/ethnicity. No significant differences were detected among the three groups in foster parent demographics, including age, race/ethnicity, education, marital status, months of foster parenting experience, or number of children in the home.

Table 1. Child and Foster Parent Characteristics by Study Condition.

| Variable | Total Sample (N = 129) |

Waitlist Control (n = 46) |

Brief PCIT (n = 48) |

Extended PCIT (n = 35) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child age (range 2—7 years) | 4.6 | 4.6 | 4.7 | 4.4 | .665 |

| Child gender (girl = 1) | 56% | 63% | 56% | 46% | .297 |

| Child race/ethnicity | |||||

| African American | 61% | 63% | 58% | 60% | .895 |

| Hispanic | 18% | 15% | 17% | 23% | .650 |

| Non-Hispanic Caucasian | 16% | 11% | 18% | 17% | .546 |

| FP a age in years (range 23–79 yrs.) |

44 | 45 | 44 | 45 | .820b |

| FP race/ethnicity | |||||

| African American | 45% | 52% | 42% | 40% | .466 |

| Caucasian | 50% | 41% | 52% | 54% | .573 |

| FP education level (range 1–5) |

3.4 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 3.2 | .566b |

| FP married | 52% | 52% | 51% | 51% | .997 |

| FP experience (range 1–480 months) |

24 | 37 | 24 | 16 | .281b |

| Number of children in home (range 1–7) |

3.0 | 3.1 | 2.8 | 3.0 | .548b |

Note.

FP = foster parent.

Test statistics are F-statistics; others are Pearson χ2. Estimates for dichotomous variables reported as percentages. Units of measurement for non-dichotomous variables reported as means except for foster parent months of experience (median).

Because randomization procedures appeared to result in group equivalence, primary analyses of PSI-SF outcomes were run using 3 × 3 mixed-model repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) and maximum likelihood estimation to test for differences in the three study conditions over three data points (i.e., baseline, 8 weeks, 14 weeks). Tests of interactions were conducted between contrast-coded vectors designating the treatment comparisons and linear and quadratic orthogonal polynomial trend contrasts representing time (Mersky et al., 2014). The DPICS-II scores consisted of observational counts, and therefore, a mixed-effects generalized linear model was used to analyze the nonlinear outcomes. Residual likelihood estimation methods were applied along with a log link function to model the Poisson distribution (Hedeker, 2005). Interactions between treatment conditions were also conducted for the DPICS-II analysis. Primary analyses retained missing observations, and used maximum likelihood procedures to obtain valid parameter estimates despite missing values. For between-group contrasts we report Cohen’s d effect size estimates, for which 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8 are considered small, medium, and large effects, respectively (Cohen, 1988). To test for robustness, analyses were also repeated under intention-to-treat assumptions. For those cases when a participant missed a data point, missing values were replaced by applying a last observation carried forward (LOCF) approach. All mixed model analyses were run in SAS 9.3 with the PROC MIXED procedure for PSI-SF outcomes and the PROC GLIMMIX procedure for DPICS-II outcomes.

Results

Primary analyses revealed no omnibus differences existed between study groups at baseline on any outcome measure. As shown in Table 2, least squares mean scores on the PSI-SF Total Stress scale indicated that parenting stress levels were high in all three groups at the study start (> 85th percentile). By 14 weeks post baseline, Total Stress scores for the two treatment conditions (brief and extended PCIT groups) decreased substantially whereas scores for the control group increased slightly at 8 weeks and then decreased at 14 weeks to below baseline levels. Between-group analyses of the Total Stress scale uncovered a significant condition-by-time interaction (p = .007) with a Cohen’s d effect size (ES) of .49, signifying an omnibus difference in the average trend among study conditions over time. The combined trend of the two treatment groups also differed from the trend of the control group when time was modeled as a linear function (p = .027; ES = .45) or as a quadratic function (p = .029; ES = .45). The significant interaction term in the quadratic model suggests that, although scores decreased slightly for the control group, the treatment groups decreased at a faster rate. Within-group analyses showed that Total Stress scores decreased significantly for the brief and extended PCIT groups (p < .001). Scores decreased for the control group as well, although within-group effects were not statistically significant (p = .086).

Table 2. Mixed Model Analyses of Variance (ANOVAs) Comparing Mean Parenting Stress Index Scores.

| Waitlist Control (G0) | Brief PCIT (G1) | Extended PCIT (G2) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | M (SE) | M (SE) | M (SE) | |||||

| Total Stress Scale | Between-Group Effects | |||||||

| (G0 vs. G1 + G2)b | (G1 vs. G2)c | |||||||

| Time 1 | 85.20 | 90.16 | 89.77 | Omnibus Testa | Linear | Quadratic | Linear | Quadratic |

|

|

||||||||

| (2.84) | (2.79) | (3.31) | p = .007 | p = .027 | p = .029 | p = .727 | p = .081 | |

| Time 2 | 86.56 | 79.15 | 83.31 | ES = .49 | ES = .45 | ES = .45 | ES = .07 | ES = .30 |

| (3.03) | (2.99) | (3.55) | Within-Group Effects d | |||||

| Time 3 | 80.57 | 77.41 | 75.35 | (G0) |

(G1) |

(G2) |

||

| (3.19) | (3.10) | (3.61) | p = .086 | p < .001 | p < .001 | |||

|

| ||||||||

| Parental Distress | Between-Group Effects d | |||||||

| (G0 vs. G1 + G2)b | (G1 vs. G2)c | |||||||

| Time 1 | 23.47 | 25.02 | 23.51 | Omnibus Testa | Linear | Quadratic | Linear | Quadratic |

|

|

||||||||

| (1.095) | (1.07) | (1.27) | p = .868 | p = .990 | p = .305 | p = .926 | p = .743 | |

| Time 2 | 23.19 | 23.56 | 22.37 | ES = .14 | ES = .02 | ES = .20 | ES = .02 | ES = .07 |

| (1.16) | (1.14) | (1.36) | Within-Group Effects d | |||||

| Time 3 | 21.95 | 23.55 | 21.91 | (G0) |

(G1) |

(G2) |

||

| (1.19) | (1.15) | (1.35) | p = .252 | p = .172 | p = .302 | |||

|

|

||||||||

| Parent-Child Dysfunctional Interaction | Between-Group Effects | |||||||

| (G0 vs. G1 + G2)b | (G1 vs. G2)c | |||||||

| Time 1 | 26.84 | 27.68 | 28.11 | Omnibus Testa | Linear | Quadratic | Linear | Quadratic |

|

|

||||||||

| (1.03) | (1.01) | (1.19) | p = .006 | p = .013 | p = .018 | p = .446 | p = .237 | |

| Time 2 | 26.53 | 22.48 | 23.85 | ES = .60 | ES = .50 | ES = .47 | ES = .16 | ES = .24 |

| (1.11) | (1.10) | (1.30) | Within-Group Effects d | |||||

| Time 3 | 23.89 | 21.81 | 20.94 | (G0) |

(G1) |

(G2) |

||

| (1.16) | (1.12) | (1.30) | p = .02 | p < .001 | p < .001 | |||

|

|

||||||||

| Difficult Child | Between-Group Effects | |||||||

| (G0 vs. G1 + G2)b | (G1 vs. G2)c | |||||||

| Time 1 | 34.89 | 37.46 | 38.14 | Omnibus Test a | Linear | Quadratic | Linear | Quadratic |

|

|

||||||||

| (1.35) | (1.32) | (1.57) | p = .002 | p = .004 | p = .164 | p = .90 | p = .02 | |

| Time 2 | 36.91 | 33.13 | 37.37 | ES = .55 | ES = .60 | ES = .14 | ES = .03 | ES = .49 |

| (1.45) | (1.43) | (1.69) | Within-Group Effects d | |||||

| Time 3 | 35.03 | 32.15 | 32.54 | (G0) |

(G1) |

(G2) |

||

| (1.52) | (1.48) | (1.72) | p = .157 | p < .001 | p = .002 | |||

Note. Coefficients are least squares means. M = mean; SE = standard error; ES = effect size reported as Cohen’s d.

Omnibus interaction tests of study condition by time.

Interaction contrasts comparing trends of waitlist control (G0) to the average of treatment conditions (G1 + G2).

Interaction contrasts comparing trends of the two treatment conditions (G1 vs. G2).

Within-group comparison of time effects for each treatment condition.

Analyses of the parental distress subscale of the PSI-SF revealed no significant between-group or within-group effects (Table 2). By contrast, analyses of the parent—child dysfunctional interaction subscale of the PSI-SF showed a significant omnibus difference existed in group trends over time (p = .006; ES = .60). The trend of the two treatment groups combined also differed from the trend of the control group on the parent—child dysfunctional interaction subscale when time was modeled as a linear function (p = .013; ES = .50) and as a quadratic function (p = .018; ES = .47). Within-group analyses of the parent—child dysfunctional interaction scale also revealed significant change over time in both the brief and extended PCIT groups (p < .001) and the control group (p = .02). For the difficult child subscale of the PSI-SF, we also detected a significant omnibus difference in group trends (p = .002; ES = .55). Between-group contrasts indicated that the combined trend of the treatment groups differed significantly from the trend of the control group when time was modeled as a linear function (p = .004; ES = .60), but not as a quadratic function. Within-group analyses uncovered significant pre-post change in the brief and extended PCIT groups only (p < .001, p = .002, respectively). Pairwise contrasts showed that there were no significant differences between the brief and extended PCIT conditions on the Total Stress scale of the PSI-SF or any of its subscales with one exception: The quadratic model for the difficult child subscale indicated the presence of a significant condition-by-time interaction effect (p = .02; ES = .49), which resulted from a more rapid decrease in mean scores reported by the brief PCIT group.

Analyses of observational data using the DPICS-II revealed a similar, consistent pattern of between-group effects (see Table 3). Results indicated that omnibus change scores differed significantly among the study groups for labeled praise (p < .001; ES = .55) as well as the composite measures of positive parenting (p < .001; ES = .39) and negative parenting (p < .001; ES = .66). The combined trend of the treatment groups also differed significantly from the control group on each of these measures (p < .001), with ES estimates ranging from .70 to .92. No significant between-group differences were detected in negative talk. In addition, no significant between-group differences were found on any DPICS-II indicators for the brief and extended PCIT conditions. However, we did discover a significant within-group change occurred for the brief and extended PCIT groups on the measures of labeled praise, positive parenting, and negative parenting (p < .001 for all values). Moreover, we found evidence of significant within-group change in negative talk for the brief PCIT group (p = .011), but not the extended PCIT group (p = .082). Results showed no significant within-group change for the control group on any of the DPICS-II indicators.

Table 3. Mixed Model Analyses of Variance (ANOVAs) Comparing Mean Dyadic Parent-Child Interaction Coding System Scores.

| Waitlist Control (G0) | Brief PCIT (G1) | Extended PCIT (G2) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Outcomes | M (SE) | M (SE) | M (SE) | |||

| Labeled Praise | Between-Group Effects | |||||

| Omnibus Testa | (G0 vs. G1 + G2)b | (G1 vs. G2)c | ||||

|

|

||||||

| Time 1 | .77 | .61 | .55 | p < .001 | p < .001 | p = .683 |

| (.35) | (.43) | (.50) | ES = .55 | ES = .70 | ES = .06 | |

| Time 2 | 1.36 | 8.58 | 10.20 | Within-Group Effects d | ||

| (.30) | (.12) | (.13) | (G0) | (G1) | (G2) | |

|

|

||||||

| p = .202 | p < .001 | p < .001 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Negative Talk | Between-Group Effects | |||||

| Omnibus Testa | (G0 vs. G1 + G2)b | (G1 vs. G2)c | ||||

|

|

||||||

| Time 1 | 7.09 | 6.88 | 8.23 | p = .232 | p = .111 | p = .490 |

| (.16) | (.17) | (.18) | ES = .23 | ES = .32 | ES = .13 | |

| Time 2 | 6.26 | 3.41 | 5.28 | Within-Group Effects d | ||

| (.19) | (.27) | (.24) | (G0) | (G1) | (G2) | |

|

|

||||||

| p = .545 | p = .011 | p = .082 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Positive Composite | Between-Group Effects | |||||

| Omnibus Testa | (G0 vs. G1 + G2)b | (G1 vs. G2)c | ||||

|

|

||||||

| Time 1 | 2.26 | 2.00 | 2.80 | p < .001 | p < .001 | p = .215 |

| (.25) | (.28) | (.27) | ES = .56 | ES = .72 | ES = .21 | |

| Time 2 | 3.73 | 18.24 | 15.41 | Within-Group Effects d | ||

| (.22) | (.10) | (.13) | (G0) | (G1) | (G2) | |

|

|

||||||

| p = .113 | p < .001 | p < .001 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Negative Composite | Between-Group Effects | |||||

| Omnibus Testa | (G0 vs. G1 + G2)b | (G1 vs. G2)c | ||||

|

|

||||||

| Time 1 | 31.21 | 38.64 | 37.91 | p < .001 | p < .001 | p = .480 |

| (.09) | (.08) | (.10) | ES = .66 | ES = .92 | ES = .13 | |

| Time 2 | 28.02 | 17.16 | 19.71 | Within-Group Effects d | ||

| (.10) | (.14) | (.15) | (G0) | (G1) | (G2) | |

|

|

||||||

| p = .293 | p < .001 | p < .001 | ||||

Note. Coefficients are least squares means. M = mean; SE = standard error; ES = effect size reported as Cohen’s d.

Omnibus interaction tests of study condition by time.

Interaction contrasts comparing trends of waitlist control (G0) to the average of treatment conditions (G1 + G2).

Interaction contrasts comparing trends of the two treatment conditions (G1 vs. G2).

Within-group comparison of time effects for each treatment condition.

Reanalyzing the data under intention-to-treat assumptions yielded results that were consistent with the results reported above. Point estimates and effect sizes were very similar to those produced by our primary analytic approach.

Discussion

Results from this randomized field trial demonstrated that implementing PCIT as a group-based intervention coupled with individualized telephone consultation was associated with reduced parenting stress and enhanced parenting behavior. We found that, as compared with the waitlist control condition, both the brief PCIT and extended PCIT interventions were associated with effect sizes that fell mostly in the medium range. Results were consistent across multiple measures and model specifications, suggesting that integrating PCIT into parent training has the potential to improve upon usual training and support services for foster parents.

The estimates we report are in line with two similar studies. Timmer and colleagues (2010) compared receipt of in-home social support with receipt of the combination of in-home PCIT and clinic-based PCIT to test the program’s association with improved foster parent outcomes. Results showed that adjunctive in-home PCIT was associated with small to medium effect size changes in self-reported parenting stress and observed indicators of parenting behavior. Our findings also align with a pilot study of Project KEEP (Price et al., 2008), which, like MTFC-P, is an extension of the original Multidimensional Treatment Foster Care model. Results showed that the KEEP intervention, which was delivered as a series of 16 in-person trainings to groups of foster parents, was associated with improved outcomes in increased positive reinforcement (d = .29), decreased frequency of behavior problems (d = .26), and increased placement stability (Chamberlain et al., 2008; Price et al., 2008).

Although our findings generally point to the efficacy of the intervention, specific results warrant further interpretation. For example, both PCIT conditions exhibited a significant decrease in scores on the PSI-SF Total Stress scale as well as the parent-child dysfunctional interaction and difficult child subscales, but not the parental distress subscale. These findings replicate two studies that showed PCIT was associated with reduced parenting stress attributed to the child’s behavior, but not parenting stress due to general parent concerns (Bagner & Eyberg, 2007; Thomas & Zimmer-Gembeck, 2012). Because child externalizing symptoms are a central treatment focus, it might be that PCIT alleviates parenting stress related specifically to the child’s behavior or interactions with the child. However, these changes might not correspond with effects on generalized stress or global parenting concerns. It is also possible that global parenting stress is a more distal outcome, is more difficult to alter relative to other related outcomes, or requires other intervention inputs to remediate. On the other hand, Timmer and colleagues (2010) found that, after receiving a standard clinic-based course of PCIT, foster parents reported significantly lower scores on the PSI-SF parental distress subscale if they also received in-home PCIT than if they received in-home social support. Thus, there is a need for additional research to disaggregate the effects of PCIT on various dimensions of parenting stress.

Analysis of observational data using the DPICS demonstrated that foster parents were able to learn and retain the specific positive parenting verbalizations and behaviors emphasized in PCIT. It is noteworthy that the effects of PCIT emerged even though adult participants had a substantial amount of previous training and parenting experience, implying that it is possible to promote growth in parenting knowledge and skill even for seasoned foster parents. However, the effects of the intervention on negative talk (e.g., “no,” “stop that”) were not as robust, which might imply that the development of new verbal and nonverbal behavior patterns might not supplant or extinguish established patterns of parental communication. It is also plausible that altering antecedent schemas and behaviors requires a longer, more intensive course of PCIT than the dosage received by participants in this study.

On the other hand, contrary to the preceding interpretation, results indicated that both treatment groups improved relative to controls, and no significant differences emerged between the brief and extended PCIT conditions over time. These findings are congruent with recent evidence indicating that parent and child change due to PCIT occurs largely in the early stages of treatment. For example, Hakman Chaffin, Funderburk, and Silovsky (2009) found that approximately 70% of the variance in change trajectories occurred within the first three sessions of the PCIT intervention. In addition, two other studies have shown that brief PCIT models yielded significant effects on child and parent outcomes (Berkovits, O’Brien, Carter, & Eyberg, 2010; Nixon et al., 2004). Additional exploration of dosage effects is needed to generate knowledge of how PCIT can be tailored to maximize efficacy and efficiency overall and according to distinct client needs.

Results and corresponding interpretations must take into account the following study limitations. First, a significant proportion of the caregivers recruited for the study chose not to enroll due to the voluntary nature of the study, disqualifying child characteristics, or loss of interest between the point of recruitment and initial study activities. Given that written consent was obtained post randomization, there might be unmeasured differences among the study participants and non-participants. It is also possible that the observed variation in child gender and foster parent experience could be linked to the study design, although the study conditions did not differ significantly on these or any other measured characteristics. Second, the modest sample size means that randomization procedures could not guarantee group equivalence on other latent variables, and that the analyses might not have been powered sufficiently to detect smaller effect sizes in pairwise contrasts. Third, data collection ceased at 14 weeks post baseline, and it is possible that the intervention effects might fade over time. Fourth, this study measured a restricted set of parenting measures, justifying further research on other indicators of adaptive and maladaptive parenting. In addition, self-report measures are subject to known reporting biases such as demand characteristics and social desirability, although our inclusion of measures based on observational data mitigates this concern to some degree. Fifth, only licensed, nonrelative foster care providers were included in the sample, owing partly to the absence of regulations requiring kinship care providers to attend in-service parent training. Therefore, our findings might not generalize to all kinship and non-kin care providers.

The above limitations notwithstanding, results should also be considered in light of several noteworthy study strengths. The use of psychometrically sound, repeated measures and mixed-model analyses enhances statistical conclusion validity. The fact that intervention effects were detected in survey and observational data as well as across multiple modeling approaches increases confidence in the robustness of the results. Moreover, randomized designs have known advantages in terms of internal validity, and it is important to underscore the fact that all study groups received usual services such as other parent training and child mental health treatments prior to and throughout the study. Therefore, the estimated effects could be regarded as conservative in relation to the effects that might have been detected in the absence of these services.

Testing the effects of the intervention relative to standard care under real-world conditions also amplifies the practical significance of the findings. PCIT is a clinically efficacious treatment, but rarely has it been implemented and tested using intervention modalities that are replicable in the child welfare system. Through the establishment of university-agency partnerships, plans to adapt PCIT were developed for the present study in order to navigate potential barriers to integrating PCIT into child welfare services. Extending the pilot study by McNeil et al. (2005), which established the feasibility of implementing PCIT with groups of foster parents, a group-based approach was adopted so that the intervention could be integrated into the context of foster parent training. Using this service portal facilitated implementation efforts, and in the future this adaptation might increase the likelihood of integrating this model into routine services.

Although parent training programs that incorporate in vivo coaching and activities to promote positive parent-child interactions are especially efficacious (Kaminski, Valle, Filene, & Boyle, 2008), foster parents receive almost exclusively didactic, conceptual training. Adapting PCIT to fit the context of foster parent training has the potential to improve upon existing training curricula by introducing opportunities for experiential learning. Arguably, some drawbacks exist to implementing PCIT in a group context, including excess stimuli that could distract participants as well as the added demands of coordinating multiple clinical and auxiliary service providers. Nevertheless, as compared with the standard outpatient model, implementing PCIT as a group-based model offers distinct clinical advantages. For example, the clinical coaching sessions in this study were adapted so that foster parents could observe other parent-child dyads engaging in CDI and PDI. As a result, intervention effects might have been augmented through social learning. In addition, group-based training offers parents the opportunity to receive social support, which could diminish potential feelings of isolation or stigma by normalizing the therapeutic process. Further, by concentrating dosage in a brief, intensive format, group training can reduce client inconvenience and burden, which is important for foster parents given that they often care for multiple children with special mental health needs.

PCIT has also shown promise as an in-home service, used as either as a primary or adjunct treatment (Galanter et al., 2012; Lanier et al., 2011; Timmer et al., 2010). Along with homework exercises, home-based telephone consultation was used to increase treatment adherence and bolster clinic-based gains. Telehealth care is growing rapidly in many fields as a means of removing barriers to care and providing services. Phone consultation is a particularly flexible and convenient modality that can be used to monitor and review clients’ progress, enhance fidelity to PCIT skills, and help clients generalize newly acquired skills into their natural environment. Ongoing communication between clinicians and foster parents can also reinforce therapeutic relationships that emerge during group training.

Group training and telephone consultation are intervention modalities that can be used to translate PCIT into efficacious and replicable services for foster families. Implementing PCIT via these and other routine service mechanisms such as supervised visitation and intensive in-home services can facilitate the process of integrating the model into standard care. In turn, access to PCIT can be expanded by allocating scarce clinical resources to a wider client base. By altering the structure as well as the location and mode of PCIT, this line of translational research holds the promise of cultivating effective, generalizable, and sustainable services for both foster families and biological families who are involved with the child welfare system.

Acknowledgements

Support for this research was provided by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Award No. 1R15HD067829-01A1.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the Bureau of Milwaukee Child Welfare and its partner agencies, SaintA and the Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin. We also thank the foster families that graciously devoted their time and effort to this project.

Contributor Information

Joshua P. Mersky, Jane Addams College of Social Work at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

James Topitzes, Helen Bader School of Social Welfare at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.

Colleen E. Janczewski, Jane Addams College of Social Work at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Cheryl B. McNeil, Department of Psychology at West Virginia University.

References

- Abidin RR. The determinants of parenting behavior. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1992;21:407–412. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp2104_12. [Google Scholar]

- Abidin RR. Parenting Stress Index (PSI) manual. 3rd ed. Psychological Assessment Resources; Odessa, FL: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bagner DM, Eyberg SM. Parent—child interaction therapy for disruptive behavior in children with mental retardation: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2007;36:418–429. doi: 10.1080/15374410701448448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth RP, Green R, Webb MB, Wall A, Gibbons C, Craig C. Characteristics of out-of-home caregiving environments provided under child welfare services. Child Welfare. 2008;87(3):5–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth RP, Lloyd EC, Green RL, James S, Leslie LK, Landsverk J. Predictors of placement moves among children with and without emotional and behavioral disorders. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2007;15:46–55. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/10634266070150010501. [Google Scholar]

- Berkovits MD, O’Brien KA, Carter CG, Eyberg SM. Early identification and intervention for behavior problems in primary care: A comparison of two abbreviated versions of parent-child interaction therapy. Behavior Therapy. 2010;41:375–387. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2009.11.002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry M. A review of parent training programs in child welfare. Social Service Review. 1988;62:302–323. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/644548. [Google Scholar]

- Burns BJ, Phillips SD, Wagner HR, Barth RP, Kolko DJ, Campbell Y, Landsverk J. Mental health need and access to mental health services by youths involved with child welfare: A national survey. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43:960–970. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000127590.95585.65. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.chi.0000127590.95585.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaffin M, Silovsky JF, Funderburk B, Valle LA, Brestan EV, Balachova T, Bonner BL. Parent-child interaction therapy with physically abusive parents: Efficacy for reducing future abuse reports. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:500–510. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.500. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006x.72.3.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain P, Price J, Leve LD, Laurent H, Landsverk JA, Reid JB. Prevention of behavior problems for children in foster care: Outcomes and mediation effects. Prevention Science. 2008;9(1):17–27. doi: 10.1007/s11121-007-0080-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11121-007-0080-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clausen JM, Landsverk J, Ganger W, Chadwick D, Litrownik A. Mental health problems of children in foster care. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 1998;7:283–296. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/a:1022989411119. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cooley ME, Veldorale-Griffin A, Petren RE, Mullis AK. Parent—Child Interaction Therapy: A meta-analysis of child behavior outcomes and parent stress. Journal of Family Social Work. 2014;17:191–208. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10522158.2014.888696. [Google Scholar]

- Denby R, Rindfleisch N, Bean G. Predictors of foster parents’ satisfaction and intent to continue to foster. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1999;23:287–303. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(98)00126-4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s0145-2134(98)00126-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorsey S, Farmer EM, Barth RP, Greene KM, Reid J, Landsverk J. Current status and evidence base of training for foster and treatment foster parents. Children and Youth Services Review. 2008;30:1403–1416. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2008.04.008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyberg SM, Nelson MM, Duke M, Boggs SR. Manual for the dyadic parent—child interaction coding system. 3rd ed. University of Florida; Gainesville: 2005. Retrieved from http://www.PCIT.org. [Google Scholar]

- Eyberg SM, Pincus D. Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory and Sutter-Eyberg Student Behavior Inventory-Revised: Professional manual. Psychological Assessment Resources; Odessa, FL: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez MA, Eyberg SM. Predicting treatment and follow-up attrition in parent—child interaction therapy. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2009;37:431–441. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9281-1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10802-008-9281-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher PA, Kim HK, Pears KC. Effects of Multidimensional Treatment Foster Care for Preschoolers (MTFC-P) on reducing permanent placement failures among children with placement instability. Children and Youth Services Review. 2009;31:541–546. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2008.10.012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2008.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher PA, Stoolmiller M. Intervention effects on foster parent stress: Associations with child cortisol levels. Development and Psychopathology. 2008;20:1003–1021. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000473. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/s0954579408000473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galanter R, Self-Brown S, Valente JR, Dorsey S, Whitaker DJ, Bertuglia-Haley M, Prieto M. Effectiveness of Parent—Child Interaction Therapy delivered to at-risk families in the home setting. Child & Family Behavior Therapy. 2012;34:177–196. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07317107.2012.707079. [Google Scholar]

- Hakman M, Chaffin M, Funderburk B, Silovsky JF. Change trajectories for parent–child interaction sequences during Parent-Child Interaction Therapy for child physical abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2009;33:461–470. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.08.003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haskett ME, Ahern LS, Ward CS, Allaire JC. Factor structure and validity of the Parenting Stress Index-Short Form. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2006;35:302–312. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3502_14. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp3502_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedeker D. Generalized linear mixed models. In: Everitt B, Howell D, editors. Encyclopedia of statistics in behavioral science. John Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, NJ: 2005. pp. 1–10. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/0470013192.bsa251. [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz SM, Hurlburt MS, Goldhaber-Fiebert JD, Heneghan AM, Zhang J, Rolls-Reutz J, Stein RE. Mental health services use by children investigated by child welfare agencies. Pediatrics. 2012;130:861–869. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1330. http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healey DM, Flory JD, Miller CJ, Halperin JM. Maternal positive parenting style is associated with better functioning in hyperactive/inattentive preschool children. Infant and Child Development. 2011;20:148–161. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/icd.682. [Google Scholar]

- Hutcheson JJ, Black MM. Psychometric properties of the Parenting Stress Index in a sample of low-income African-American mothers of infants and toddlers. Early Education and Development. 1996;7(4):381–400. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15566935eed0704_5. [Google Scholar]

- Jones G, Morrissette PJ. Foster parent stress. Canadian Journal of Counselling and Psychotherapy. 1999;33(1):13–27. Retrieved from http://cjc-rcc.ucalgary.ca/cjc/index.php/rcc/article/view/127/308. [Google Scholar]

- Kaminski JW, Valle LA, Filene JH, Boyle CL. A meta-analytic review of components associated with parent training program effectiveness. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:567–589. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9201-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10802-007-9201-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keil V, Price JM. Externalizing behavior disorders in child welfare settings: Definition, prevalence, and implications for assessment and treatment. Children and Youth Services Review. 2006;28:761–779. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2005.08.006. [Google Scholar]

- Lanier P, Kohl PL, Benz J, Swinger D, Moussette P, Drake B. Parent—Child Interaction Therapy in a community setting: Examining outcomes, attrition, and treatment setting. Research on Social Work Practice. 2011;21:689–698. doi: 10.1177/1049731511406551. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/e621642012-167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leach LS, Christensen H. A systematic review of telephone-based interventions for mental disorders. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare. 2006;12:122–129. doi: 10.1258/135763306776738558. http://dx.doi.org/10.1258/135763306776738558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Holland TP. Evaluating the effectiveness of foster parent training. Research on Social Work Practice. 1991;1:162–174. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/104973159100100204. [Google Scholar]

- Linares LO, Montalto D, Li M, Oza VS. A promising parenting intervention in foster care. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:32–41. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.1.32. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006x.74.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacGregor TE, Rodger S, Cummings AL, Leschied AW. The needs of foster parents: A qualitative study of motivation, support, and retention. Qualitative Social Work. 2006;5:351–368. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1473325006067365. [Google Scholar]

- McNeil CB, Hembree-Kigin T. Parent-Child Interaction Therapy. 2nd ed. Springer; New York, NY: 2010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-88639-8. [Google Scholar]

- McNeil CB, Herschell AD, Gurwitch RH, Clemens-Mowrer L. Training foster parents in Parent-Child Interaction Therapy. Education and Treatment of Children. 2005;28:182–196. ERIC Document Number: EJ704947. [Google Scholar]

- Mersky JP, Topitzes J, Grant-Savela SD, Brondino MJ, McNeil CB. Adapting Parent—Child Interaction Therapy to foster care: Outcomes from a randomized trial. Research on Social Work Practice. 2014 Advance online publication. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1049731514543023. [Google Scholar]

- Murray L, Tarren-Sweeney M, France K. Foster carer perceptions of support and training in the context of high burden of care. Child & Family Social Work. 2011;16:149–158. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2206.2010.00722.x. [Google Scholar]

- Newton RR, Litrownik AJ, Landsverk JA. Children and youth in foster care: Disentangling the relationship between problem behaviors and number of placements. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2000;24:1363–1374. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(00)00189-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s0145-2134(00)00189-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon RD, Sweeney L, Erickson DB, Touyz SW. Parent—child interaction therapy: One-and two-year follow-up of standard and abbreviated treatments for oppositional preschoolers. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2004;32:263–271. doi: 10.1023/b:jacp.0000026140.60558.05. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/b:jacp.0000026140.60558.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oosterman M, Schuengel C, Wim Slot N, Bullens RA, Doreleijers TA. Disruptions in foster care: A review and meta-analysis. Children and Youth Services Review. 2007;29:53–76. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2006.07.003. [Google Scholar]

- Orme JG, Buehler C. Foster family characteristics and behavioral and emotional problems of foster children: A narrative review. Family Relations. 2001;50:3–15. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2001.00003.x. [Google Scholar]

- Pocock SJ, Simon R. Sequential treatment assignment with balancing for prognostic factors in the controlled clinical trial. Biometrics. 1975;31:103–115. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2529712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponnet K, Mortelmans D, Wouters E, Van Leeuwen K, Bastaits K, Pasteels I. Parenting stress and marital relationship as determinants of mothers’ and fathers’ parenting. Personal Relationships. 2013;20:259–276. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2012.01404.x. [Google Scholar]

- Price JM, Chamberlain P, Landsverk J, Reid JB, Leve LD, Laurent H. Effects of a foster parent training intervention on placement changes of children in foster care. Child Maltreatment. 2008;13:64–75. doi: 10.1177/1077559507310612. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1077559507310612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puddy RW, Jackson Y. The development of parenting skills in foster parent training. Children and Youth Services Review. 2003;25:987–1013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s0190-7409(03)00106-3. [Google Scholar]

- Ruma PR, Burke RV, Thompson RW. Group parent training: Is it effective for children of all ages? Behavior Therapy. 1996;27:159–169. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s0005-7894(96)80012-8. [Google Scholar]

- Schuhmann EM, Foote RC, Eyberg SM, Boggs SR, Algina J. Efficacy of Parent—Child Interaction Therapy: Interim report of a randomized trial with short-term maintenance. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1998;27:34–45. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2701_4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp2701_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas R, Zimmer-Gembeck MJ. Behavioral outcomes of parent—child interaction therapy and Triple P—Positive Parenting Program: A review and meta-analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2007;35(3):475–495. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9104-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10802-007-9104-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas R, Zimmer-Gembeck MJ. Parent—Child Interaction Therapy: An evidence-based treatment for child maltreatment. Child Maltreatment. 2012;17:253–266. doi: 10.1177/1077559512459555. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1077559512459555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmer SG, Urquiza AJ, Zebell N. Challenging foster caregiver—maltreated child relationships: The effectiveness of parent—child interaction therapy. Children and Youth Services Review. 2006;28:1–19. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2005.01.006. [Google Scholar]

- Timmer SG, Zebell NM, Culver MA, Urquiza AJ. Efficacy of adjunct in-home coaching to improve outcomes in Parent-Child Interaction Therapy. Research on Social Work Practice. 2010;20(1):36–45. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1049731509332842. [Google Scholar]

- Vanderfaeillie J, Van Holen F, Trogh L, Andries C. The impact of foster children’s behavioural problems on Flemish foster mothers’ parenting behaviour. Child & Family Social Work. 2012;17:34–42. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2206.2011.00770.x. [Google Scholar]

- Vanschoonlandt F, Vanderfaeillie J, Van Holen F, De Maeyer S, Robberechts M. Parenting stress and parenting behavior among foster mothers of foster children with externalizing problems. Children and Youth Services Review. 2013;35(10):1742–1750. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2013.07.012. [Google Scholar]

- Webster-Stratton C, Reid M. Adapting the Incredible Years, an evidence-based parenting programme for families involved in the child welfare system. Journal of Children’s Services. 2010;5:25–42. http://dx.doi.org/10.5042/jcs.2010.0115. [Google Scholar]

- Werba BE, Eyberg SM, Boggs SR, Algina J. Predicting outcome in Parent-Child Interaction Therapy success and attrition. Behavior Modification. 2006;30:618–646. doi: 10.1177/0145445504272977. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0145445504272977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]