Abstract

The digital imaging and communications in medicine (DICOM) protocol is the leading standard for image data management in healthcare. Imaging biomarkers and image-based surrogate endpoints in clinical trials and medical registries require DICOM viewer software with advanced functionality for visualization and interfaces for integration. In this paper, a comprehensive evaluation of 28 DICOM viewers is performed. The evaluation criteria are obtained from application scenarios in clinical research rather than patient care. They include (i) platform, (ii) interface, (iii) support, (iv) two-dimensional (2D), and (v) three-dimensional (3D) viewing. On the average, 4.48 and 1.43 of overall 8 2D and 5 3D image viewing criteria are satisfied, respectively. Suitable DICOM interfaces for central viewing in hospitals are provided by GingkoCADx, MIPAV, and OsiriX Lite. The viewers ImageJ, MicroView, MIPAV, and OsiriX Lite offer all included 3D-rendering features for advanced viewing. Interfaces needed for decentral viewing in web-based systems are offered by Oviyam, Weasis, and Xero. Focusing on open source components, MIPAV is the best candidate for 3D imaging as well as DICOM communication. Weasis is superior for workflow optimization in clinical trials. Our evaluation shows that advanced visualization and suitable interfaces can also be found in the open source field and not only in commercial products.

Keywords: Software, DICOM, Evaluation, Data capture, Integration, Interfaces, Display

Background

Digital imaging and communications in medicine (DICOM) has been released in 1993 by the American College of Radiology (ACR) and the National Electrical Manufacturers Association (NEMA). Nowadays, DICOM has been established as the leading standard for image data management in medical applications [1]. The protocol is applied to capture, exchange, and archive image data in picture archiving and communication systems (PACS). Using DICOM software, a subject’s image data is viewed and analyzed by physicians in hospitals, as well as in clinical research.

Accordingly, a lack of interfaces for system integration has been identified as a key issue in clinical research [2, 3], where systems still are operated standalone. The demand on workflow-optimized and integrated systems for imaging-based clinical trials increases [4]. For instance, powerful functionality for rendering of three-dimensional (3D) volume data such as computer tomography (CT) may be required within the electronic case report form (eCRF) to decide on inclusion or exclusion of subjects in clinical trials [5] or in rare disease registries [6]. Almost 370 free DICOM software projects are currently listed in the “I Do Imaging” database1, and finding an optimal viewer turns challenging, particularly for research applications.

In 1998, Honea et al. have published an investigation of commercial personal computer (PC)-based DICOM viewers for clinical review and home teleradiology stations [7]. The authors identified important functionality, such as multiple windowing levels, distance and angle measurements, as well as storage of annotations and built up a catalog of criteria. The evaluation was performed by an ability check during demonstrations of five various viewer projects at a children’s hospital.

In 2003, Horii has presented a survey of free and commercial DICOM viewers [8]. He analyzed viewing capabilities by means of supported DICOM object types, included image processing methods, and the ability to export images. Horii stated that tools, which are easy to use and include rich functionality, can also be found in the open source field.

In 2007, Nagy has published a list of suitable DICOM open source tools [9]. He included server, viewer, image processing, teaching file tools, web-based PACS, and general toolkits, which include conversion and code libraries.

In 2008, a first systematic evaluation was performed by Liao et al. The survey has been focused on free and standalone non-diagnostic DICOM viewers [10]. In this work, 21 software projects with a graphical user interface (GUI) have been analyzed regarding data import, data export, header viewing, two-dimensional (2D) and 3D image viewing, support, portability, workability, and usability. All criteria have been defined as “yes”/“no” categories except workability and usability. These aspects have been assessed rather qualitatively (e.g., by subjective percent values). Optimal DICOM viewers have been suggested for inexperienced users, data conversion, and volume rendering.

The publications of Nagy and Horii rather focused on a description of available tools than comparing them. Published almost 10 years ago, Liao’s results are considered as expired. Furthermore, all evaluations completely disregard the fact that DICOM viewers are usually not designed as standalone software. Tight coupling of systems allows easy access to shared data. Integrating data, context, and functionality of components improve the workflow of medical personal, particularly in clinical trials [5]. Various approaches have been published, where DICOM viewer tools have been integrated into system architectures [11–13]. For this, a compatible platform and the availability of interfaces are essential.

In this paper, a comprehensive evaluation of state-of-the-art DICOM viewer software is performed. Besides an extensive analysis of the viewing functionality, our work is focused on platforms and interfaces. Three applications are identified and objective criterions are developed for comparison. Preliminary results have been already presented at the SPIE Medical Imaging conference [14]. In this paper, more software tools have been included, and the evaluation has been re-performed on revised criterions.

Methods

Use Cases

Various use cases for viewing of subject’s DICOM data are conceivable. Each use case has its own focus and appreciates certain functionality of DICOM viewers. On a certain level of abstraction, we determine the following three use cases:

Central Viewing: In hospitals, patient’s DICOM data is usually viewed on a central client system. For this, the data has to be gathered from the PACS, which requires a broad availability of DICOM interfaces. In this use case, stable 2D viewing functionality is rather needed than sophisticated 3D rendering.

Decentral Viewing: In multi-centered clinical trials, patient’s data is shared between sites [15]. Long distances have to be bridged for subject’s image data. Hence, an integrated and decentral system provides the optimal workflow in this use case, which can be satisfied by web-based technologies. DICOM viewing in clinical trials also requires rather effective slice-by-slice display than advanced 3D-viewing functionality.

Advanced Viewing: In some cases, advanced viewing functionality such as sophisticated 3D image rendering and analysis of volumetric data is important. Powerful visualization is obtained combining image processing with advanced rendering techniques. Primarily, comprehensive system resources are needed. System integration plays a minor role.

Tool Selection

The software tools included in our survey have been collected by a non-systematic Internet survey using Google and the “I Do Imaging” database. The survey has been primarily focused on projects, which are distributed under an open source license (e.g., GNU General Public License (GPL), Berkeley Software Distribution (BSD) license). However, some free and commercial tools have been included too.

Comparison Criteria

With respect to the three scenarios, a catalog of 26 criteria have been composed concerning requirements for (i) platform, (ii) interfaces, (iii) support, (iv) 2D rendering, and (v) 3D rendering. Interface criteria are based on functionality which has been valued as advantageous regarding our use cases. The viewing criteria are based on the work of Liao et al. Focusing on integration of systems, criteria such as data import and export have been discharged. To avoid subjectivity, all criteria are designed as simple “yes” (+) or “no” (−) categories.

Platform

The platform criteria concern the viewer’s system environment. Criteria for standalone, web, multi-platform, and mobile device software are included.

C1 – Standalone

Standalone applications are designed to be only runnable on specific operating systems (e.g., Windows, Linux, or Mac OS). Usually, software versions for various platforms exist.

C2 – Web-based

Web applications are running on a web server and can be accessed by client systems via modern browsers. Web servers are usually based on a Linux or Windows operating system.

C3 – Multi-platform

Some programming languages (e.g., Java) are platform-independent. Platform-independent software can be executed on standalone systems (e.g., using Java runtime environment (JRE)) or transferred by the web server to a client system (e.g., using Java Web Start).

C4 – Mobile

In case the DICOM viewer provides a suitable GUI, medical images can be viewed on mobile devices such as smartphones or tablets.

Interfaces

Aiming at communication with other systems, interfaces are needed:

C5 – C-STORE SCP

DICOM C-STORE service class provider (SCP) is an operation that allows transfer and storage of DICOM objects into connected systems [1, 16]. In case of the role as SCP, the viewer passively receives data from other DICOM nodes (e.g., PACS).

C6 – C-STORE SCU

In case of the role as C-STORE service class user (SCU), the viewer actively stores data into other DICOM nodes.

C7 – Query-Retrieve

DICOM query and retrieve (Q/R) allows a system to actively request and gather data from other DICOM nodes.

C8 – WADO

The Web access to DICOM objects (WADO) service allows a system to offer other systems access to DICOM objects via web protocols [17].

C9 – Parameter Transfer

Parameter calls are used to transfer data (e.g., settings) directly on invocation to a software application. For instance, parameter calls may be used to forward context information.

Support

Support requirements identify in which way helpful information for the software is provided.

C10 – Documentation

Written documentation for the software is available (e.g., manuals).

C11 – Mail

A mailing list is offered to get support via mail.

C12 – Forum

A Web-based forum for support is offered.

C13 – Wiki

A wiki Web page is available for users.

2D Viewing

Focusing on viewing functionality, some viewer features are in special useful viewing 2D images:

C14 – Scrolling

During viewing of images in a DICOM series, usability can be improved by reduced mouse interaction. Mouse interaction can be decreased, for instance, by offering the possibility to move to the next or previous image by simply scrolling with the mouse wheel or by using the up and down keys on the keyboard.

C15 – Metadata

Header viewing functionality includes parsing and displaying of DICOM object’s metadata. This functionality should include image- (e.g., resolution), study- (e.g., subject’s identifier), and vendor-specific DICOM tags (e.g., special settings of recording device).

C16 – Information Overlay

Important information should be visualized in the display window as an overlay. For instance, the current position in the DICOM series or subject’s pseudonym should be directly shown.

C17 – Windowing

Windowing controls brightness and contrast of the displayed image. In case structures of the image are not optimally visualized, these values can be adjusted.

C18 – Pseudo Colors

Pseudo-color look up tables (LUT) map grey values of the image to pseudo-colors. This improves the visual effect.

C19 – Histogram

Histograms visualize the occurrences and distribution of color values in the images. These statistics describe meaningful image characteristics.

C20 – Measurements

Measurements allow drawing (e.g., lines) and analysis (e.g., distances, angles) of geometric figures in the image. Since the DICOM header often contains calibration information (e.g., pixel to centimeters relation), representative results can be determined.

C21 – Annotations

Results of image viewing (e.g., by measurements, text annotations) should be storable for later purposes. The data is usually stored in the image bitmap or in the metadata header.

3D Viewing

In contrast to 2D images, other features are needed in case 3D volume data is viewed:

C22 – Secondary Reconstruction

Usually, medical volume data is acquired along one body axis (e.g., transversal). In some cases, it is important to view the data in other directions (e.g., sagittal or coronal) to improve visualization of certain structures. For this, functionality for reconstruction of a secondary axis based on the primary direction has to be provided.

C23 – Slice Cube

Volume slices typically can be better displayed at a particular position. Slice cube functionality allows to independently adjust the position of the various slice axes (e.g., transversal, sagittal, or coronal) in the volume model. During this, the slices themselves are shown in a separate window.

C24 – Volume Rendering

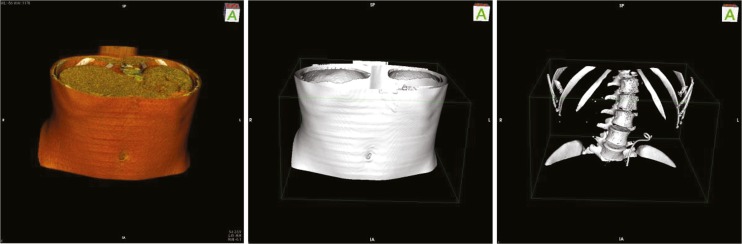

By volume rendering, 3D image data is directly visualized as volume. The user can interact with the volume by rotating, translating or scaling (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

DICOM Library data set visualized by (i) volume rendering, (ii) transfer, and (iii) surface generation functionality in OsiriX Lite [14]

C25 – Transfer Function

Transfer functionality is used to map grey values of image voxels to opacity values of tissue types (e.g., bones). Structures in the image matching the grey values are highlighted. Unmapped grey values are shown transparent. Specific structures become more clearly visible.

C26 – Surface Generation

Various algorithms (e.g., marching cubes) can be applied to calculate surfaces of voxels, which share the same grey values. Surface representations can also be applied to improve the visualization of certain image structures.

Evaluation

General and integration requirements have been evaluated on public information provided by the developers or vendors. In contrast, viewing functionality has been investigated by the authors themselves. For this, standalone- and platform-independent tools have been installed on a local system (Windows 7 Enterprise Service Pack 1, 64-Bit Genuine Intel CPU 1.60 GHz, 3GB RAM). Aiming at reproducibility, the criteria have been verified using public available datasets. The “DICOM Samples CT” dataset is offered by DICOM library2 and contains a series of 361 CT images. In this data set, JPEG 2000 is used as transfer syntax. Since, this caused issues in some viewers, another dataset has been included. The “CT0001” DICOM dataset is provided by the NEMA3 and uses explicit little endian as transfer syntax, which seems to be more broadly supported by the viewers. The data set includes a series with 153 CT images. The evaluation of web applications is based on demo systems. The demo systems have been provided by the “I Do Imaging” website or the software developers. Since the demo applications usually do not allow import of data sets, the criteria have been investigated using already available data sets. In general, we always remark, which dataset has been exactly used (Table 1).

Table 1.

Included DICOM viewer projects with version, reference, and used data set

| Name | Version | Reference | Dataset |

|---|---|---|---|

| Open Source Viewer | |||

| 3D Slicer | 4.3.1 | http://www.slicer.org/ | DICOM Library |

| BioImageSuite | 3.0.1 | http://bioimagesuite.yale.edu/ | DICOM Library |

| Cornerstone | 2014-05-014 | https://github.com/chafey/cornerstone/ | MISTER^MR |

| DWV | 0.8.0 | https://github.com/ivmartel/dwv/ | Baby MRI |

| Eviewbox | 2013-04-214 | http://eviewbox.sourceforge.net/ | NEMA |

| EzDICOM | 2004-12-024 | http://www.mccauslandcenter.sc.edu/mricro/ezdicom/ | NEMA |

| Gingko CADx | 3.7.0 | http://ginkgo-cadx.com/en/ | DICOM Library |

| Image J | 1.48 | http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/ | NEMA |

| IOviyam | 2.0Beta | http://oviyam.raster.in/ | CT^HEAD |

| MicroView | 2.1.2 | http://microview.sourceforge.net/ | DICOM Library |

| MIPAV | 7.1.1 | http://mipav.cit.nih.gov/ | DICOM Library |

| OpenDicomViewer | 0.9.0 | http://sourceforge.net/projects/opendicomviewer/ | NEMA |

| Oviyam | 2.0 | http://oviyam.raster.in/ | DICOM Library |

| Slice::Drop | 2014-12-054 | http://slicedrop.com/ | DICOM Library |

| Weasis | 2.0.1 | http://www.dcm4che.org/confluence/display/WEA/Home | DICOM Library |

| XMedCon | 0.13.0 | http://xmedcon.sourceforge.net/ | NEMA |

| Free Viewer | |||

| DicomWorks | 1.3.5 | http://www.dicomworks.com/ | NEMA |

| JiveX Dicom Viewer | 4.6.2 RC05 | http://www.visus.com/ | DICOM Library |

| MediINRIA | 1.9.4 | http://med.inria.fr/ | DICOM Library |

| MedImaView | 1.8 | http://www.dicom-solutions.com/ | NEMA |

| MRIcro | 1.40 | http://www.mricro.com/ | DICOM Library |

| OsiriX Lite | 6.0.2 | http://www.osirix-viewer.com/ | DICOM Library |

| Phillips DICOM Viewer | 3.0 SP3 | http://www.healthcare.philips.com/main/about/connectivity/ | NEMA |

| Tomovision | 2.1-rev5 | http://www.tomovision.com/ | NEMA |

| Commercial Viewer | |||

| JiveX Mobile | 4.6.3 RC03 | http://www.visus.com/ | Anonymized |

| MedDream | 2.0.8 | http://www.softneta.com/ | DICOM Library |

| RadiAnt | 1.9.16 | http://www.radiantviewer.com/ | DICOM Library |

| Xero (Agfa) | 2014.1 | http://www.agfahealthcare.com/ | CT ABDOMEN BILE |

4No version number found, identified by revision date

Results

Twenty-eight DICOM viewer projects have been included in our survey (Table 2). Sixteen of twenty-one projects of Liao et al.’s work are incorporated. The projects Julius, syngo FastView, and UniView have not been available anymore. The viewer Amide and FPImage seems to be no longer maintained, since no version running on our 64-Bit Windows system was available.

Table 2.

Results of the DICOM viewer survey

| Platforms | Interface | Support | 2D viewing | 3D Viewing | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standalone | Web | Multi-platform | Multi-platform mobile | C-STORE SCP | C-STORE SCU | DICOM Q/R | WADO | Parameter | Documentation | Forum | Wiki | Scrolling | Header | Overlay | Windowing | Pseudo Colors | Histogram | Measurements | Annotations | Secondary | Slice Cube | Volume | Transfer | Surface | ||

| Name | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 | C6 | C7 | C8 | C9 | C10 | C11 | C12 | C13 | C14 | C15 | C16 | C17 | C18 | C19 | C20 | C21 | C22 | C23 | C24 | C25 | C26 |

| Open Source Viewer | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3D Slicer | + | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | + |

| BioImageSuite | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | −+ | − | − | + | + | + | − | − | |

| Cornerstone | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | +5 | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| DWV | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | +6 | − | +7 | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Eviewbox | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | −8 | − | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| ezDICOM | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | +9 | − | +9 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| Gingko CADx | + | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| Image J | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | +10 | + | − | − | − | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | +11 | + | + | + | + | + |

| iOviyam | − | +12 | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | − | −13 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| MicroView | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | + | + | + | − | + | + | − | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | + |

| MIPAV | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | +14 | + | + | + | + | + |

| OpenDicomViewer | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Oviyam | − | +15,16 | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | − | −+ | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| Slice::Drop | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | +17 | +17 | − | − | − | |

| Weasis | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | +18 | + | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | +19 | − | − | − | − | − |

| XMedCon | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | +20 | +20 | − | − | − | +20 | − | − | − | − |

| Free Viewer | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| DicomWorks | +21 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| JiveX Dicom Viewer | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | +11 | − | − | − | − | − |

| MediINRIA | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | − | + | −22 | + | +23 | + | − | − | − | + | + | + | − | + |

| MedImaView | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | −24 | + | − | − | + | + | − | + | + | −25 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| MRIcro | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | +26 | +26 | − | +26 | +26,27 | −25 | − | +11,26 | +26 | − | +26 | − | − |

| OsiriX Lite | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Phillips DICOM Viewer | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | +28 | +28 | +28 | +28 | +28 | − | +28 | +28 | − | − | − | − | − |

| Commercial Viewer | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tomovision | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | +29 | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| ViewerJiveX Mobile | − | +30 | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| MedDream | − | +31 | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | + | − | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| RadiAnt | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| Xero | − | + | − | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | + | + | − | + | −32 | + | − | + | +33 | − |

5Via additional CornerstoneWADOImageLoader plugin, 6Conquest, DCM4CHEE or Orthanc PACS for WADO required, 7comprehensive documentation in wiki, 8Forum offline, 9Displays only first slice of test data, 10Using startup macro feature, 11Saves annotations in other formats, but not DICOM, 12Requires Oviyam, 13Designated, but not working, 14Annotated objects could not be reopened, 15Requires DCM4CHEE PACS, 16Runs only with Google Chrome, 17Does not recognize dataset as volume, 18DCM4CHEE PACS Connector plugin needed, 19Only via screenshot, 20Shows every slice of a multi-frame DICOM file separately, 21Only executable on Windows with administrator rights, 22Only technical information, no subject/study related information, 23Bad resolution and grayscale, 24Only commercial, 25Shows initial histogram only, 26Does not open DICOM, but files can be converted to NIFTI, 27Pseudo coloring did not affect visualization of test data, 28Compression artifacts, 29Only on single multi-frame DICOM files, 30Requires JiveX communication server or PACS, 31Requires PACS (supports Conquest, PacsOne, ClearCanvas or DCM4CHEE), 32Images cannot be stored, 34Seems to be not working correctly in demo

Out of the 28 projects, 16 tools are licensed as open source, 8 as free, and 4 as commercial products. 15 viewers are designed as standalone, 8 as web-based, and 5 as platform-independent software. In addition, 7 tools also provide GUIs for mobile devices. Interfaces for DICOM C-STORE as SCP and SCU, as well as Q/R, are supported by 4 and 5 tools, respectively. WADO is provided by 7 and parameter transfer by 5 viewers. However, C-STORE SCP, SCU and Q/R interfaces are almost entirely offered by standalone tools. Only MIPAV as the platform-independent and Xero as the web tool support at least one DICOM interface too. In contrast, excluding OsiriX, GingkoCADx, and Weasis, WADO is only supported by web- and platform-independent solutions. In total, GingkoCADx and OsiriX supply the most interfacing possibilities. Only parameter transfer seems to not be possible with both viewers.

A total of 13 image viewing criteria have been included. Eight requirements for 2D and five requirements for 3D exist. On the average, a total of 5.89 image viewing criteria are fulfilled, 4.46 of the 2D and 1.43 of the 3D viewing criteria Concerning only standalone viewers, a mean of 4.60 and 1.67 criteria are met for 2D and 3D viewing, respectively. On the other hand, for web-based viewers, 3.50 2D and 0.625 3D viewing criteria are met on the average. With 5.60 2D and 2.00 fulfilled 3D image viewing criteria, platform-independent tools achieved the highest values here.

The most 2D requirements of standalone, web-based, and platform-independent viewers are met by GingkoCADx, OsiriX and Phillips DICOM viewer (all 7 criteria), Oviyam and DVW (both 5 criteria), and MIPAV (8 criteria), respectively. Regarding 3D viewing, OsiriX Lite and MicroView fulfill the most criteria of standalone (both 5 criteria), Xero (3 criteria) of web-based, and ImageJ as well as MIPAV (both 5 criteria) of platform-independent viewers.

Discussion

Focusing on research, flexible low-budget software solutions are advantageous, in particular concerning investigator initiated trials (IIT). Here, open source tools have been recommended over free or commercial products [18]. As our survey shows, open source tools are on a par with commercial software. In fact, they reached partly better scores, which is also in line with the findings of Horii [8].

Our survey does not yield an overall best candidate. There is no viewer fulfilling all criteria we have defined. Each application has its own focus and requires particular features. Thus, significance is achieved by comparing the viewers with respect to use cases.

In the central viewing use case, subject’s routine data has to be gathered from hospital’s infrastructure for visualization in the viewer. This can be done by sending subject’s data to the viewer or by retrieving the images from the hospital’s PACS. In both cases, DICOM interfaces are necessary. Since data is immediately fetched from hospital’s routine, usually high security regulations have to be satisfied. Focusing on DICOM, the viewer GingkoCADx, MIPAV, and OsiriX Lite support the C-STORE as SCP and SCU, as well as the Q/R interface. However, MIPAV fulfills the most 2D criteria in this collection.

In clinical trials, subject’s data is, today, multi-center captured via so-called electronic case report forms (eCRFs) [19, 20]. Here, it is advantageous to integrate the DICOM viewer directly into the data-storing systems. Decentral viewing of image data within the eCRF optimally supports the workflow of the study personnel [5]. Since eCRFs are, today, usually offered via web, only web- or platform-independent viewers can be integrated. Data and context integration is necessary, which can be provided by WADO and parameter transfer, respectively. Oviyam and Weasis are the only web-based and platform-independent candidates, which are utilized with WADO and parameter transfer interfaces. Both projects are open source. However, Weasis slightly beats Oviyam regarding 2D image viewing by two criteria. On the other hand, Oviyam could be extended by iOviyam for support of mobile devices. However, we recommended Weasis as optimal viewer for this use case. In our opinion, pseudo-coloring and annotations are yet more important than mobile device support.

In the advanced viewing use case, 3D volume visualization is needed. However, the 3D performance of web browsers is—at least up to today—still restricted. Hence, web applications are not really suitable for 3D rendering. This is also underlined by the low 3D imaging score of web tools in our survey. Standalone or platform independent viewers are more preferable. Analyzing our results, the highest score regarding 3D imaging is reached by ImageJ, MicroView, MIPAV, and OsiriX Lite. Each tool fulfills all 3D viewing criteria. However, we recommend the open source tool MIPAV, since it satisfies all 2D viewing criteria as well. This might be useful during viewing of single 3D slices. Of course, there are other application scenarios other than the three we defined. Recently, Lo Presti et al. analyzed 26 open source and commercial DICOM viewers with regard to their ability to read in 3D models from a PACS, which are generated from external segmentation systems, such as the visualization toolkit (VTK) [21]. For this special-use case, they identified Synapse 3D and OsiriX as optimal. Although their results are based on different evaluation criterions than those we have used for the advanced viewing-use case, OsiriX reached the highest score in both evaluations.

Conclusion

As our evaluation shows, rich functionality and suitable interfaces can be also found in the open source field of DICOM viewer software. Excellent software must not always be invaluable and is also available for low-budget research, e.g., IITs. However, each tool has its strengths and weaknesses; an all-rounder solution does not exist. However, this work suggests optimal candidates of the large pool of DICOM tools for common applications. In general, we identified the open source tools MIPAV and Weasis as superior. As we have shown in our previous work, a good choice of components simplifies the build-up of a suitable system architecture [5]. Of course, new interfaces such as DICOM Store over the Web by Representations State Transfer (STOW-RS) [22] arise and have to be considered to find an optimal viewer candidate in the future.

Footnotes

References

- 1.Mildenberger P, Eichelberg M, Martin E. Introduction to the DICOM standard. Eur Radiol. 2002;12(4):920–7. doi: 10.1007/s003300101100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sung NS, Crowley WF, Genel M, Salber P, Sandy L, Sherwood LM, et al. Central challenges facing the national clinical research enterprise. JAMA. 2003;289(10):1278–87. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.10.1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ghosh S, Matsuoka Y, Asai Y, Hsin K, Kitano H. Software for systems biology: from tools to integrated platforms. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:821–32. doi: 10.1038/nrg3096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang X, Liu BJ, Martinez C, Zhang X, Winstein CJ: Development of a novel imaging informatics-based system with an intelligent workflow engine (IWEIS) to support imaging-based clinical trials. Comput Biol Med 2015. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Haak D, Page C, Reinartz S, Krüger T, Deserno TM: DICOM for clinical research: PACS-integrated electronic data capture in multi-center trials. J Digit Imaging 28(5):558–66, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Deserno TM, Haak D, Brandenburg V, Deserno V, Classen C, Specht P. Integrated image data and medical record management for rare disease registries. A general framework and its instantiation to the German Calciphylaxis Registry. J Digit Imaging. 2014;27(6):702–13. doi: 10.1007/s10278-014-9698-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Honea R, McCluggage CW, Parker B, O’Neall D, Shook KA. Evaluation of commercial PC-based DICOM image viewer. J Digit Imaging. 1998;11(S1):151–5. doi: 10.1007/BF03168289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horii C: DICOM image viewers: a survey. In: Medical Imaging 2003: SPIE; 2003. (SPIE Proceedings) p 251–9

- 9.Nagy P. Open source in imaging informatics. J Digit Imaging. 2007;20(S1):1–10. doi: 10.1007/s10278-007-9056-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liao W, Deserno TM, Spitzer K. Evaluation of free non-diagnostic DICOM software tools. In: Medical Imaging: SPIE; 2008. (SPIE Proceedings) p. 691903–12

- 11.Bernarding J, Thiel A, Grzesik A. A JAVA-based DICOM server with integration of clinical findings and DICOM-conform data encryption. Int J Med Inform. 2001;64(2-3):429–38. doi: 10.1016/S1386-5056(01)00213-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hernandez JA, Acuna CJ, de Castro M, Marcos E, Lopez M, Malpica N. Web-PACS for multicenter clinical trials. IEEE Trans Inf Technol Biomed. 2007;11(1):87–93. doi: 10.1109/TITB.2006.879601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luccichenti G, Cademartiri F, Pichiecchio A, Bontempi E, Sabatini U, Bastianello S. User Interface of a teleradiology system for the MR assessment of multiple sclerosis. J Digit Imaging. 2010;23(5):632–8. doi: 10.1007/s10278-009-9222-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haak D, Page CE, Kabino K, Deserno TM. Evaluation of DICOM viewer software for workflow integration in clinical trials. In: Medical Imaging: SPIE; 2015. p. 94180 (SPIE Proceedings).

- 15.Deserno TM, Deserno V, Haak D, Kabino K. Digital imaging and electronic data capture in multi-center clinical trials. Stud Health Technol Inform 216:930, 2015 [PubMed]

- 16.Bidgood WD, Horii SC, Prior FW, Syckle DE. Understanding and using DICOM, the data interchange standard for biomedical imaging. In: Wong STC, editor. Medical image databases. Boston: Springer US; 1998. pp. 25–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koutelakis GV, Lymperopoulos DK: PACS through web compatible with DICOM Standard and WADO Service: advantages and implementation. In: 2006 International Conference of the IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. p. 2601-5 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.DeLano WL: The case for open-source software in drug discovery. Drug Discov Today 10(3):213–7, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Leroux H, McBride S, Gibson S: On selecting a clinical trial management system for large scale, multi-centre, multi-modal clinical research study. Stud Health Technol Inform 168:89–95, 2011 [PubMed]

- 20.Franklin JD, Guidry A, Brinkley JF: A partnership approach for electronic data capture in small-scale clinical trials. J Biomed Inform 44:103–108, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Lo Presti G, Carbone M, Ciriaci D, Aramini D, Ferrari M, Ferrari V: Assessment of DICOM viewers capable of loading patient-specific 3D models obtained by different segmentation platforms in the operating room. J Digit Imaging 28(5):518–527, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Le Maitre A, Fernando J, Morvan Y, Mevel G, Cordonnier E: Comparative performance investigation of DICOM C-STORE and DICOM HTTP-based requests. In: 2014 36th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC). p. 1350–1353 [DOI] [PubMed]