Abstract

Digital whole slide imaging (WSI) is an emerging technology for pathology interpretation, with specific challenges for dermatopathology, yet little is known about pathologists’ practice patterns or perceptions regarding WSI for interpretation of melanocytic lesions. A national sample of pathologists (N = 207) was recruited from 864 invited pathologists from ten US states (CA, CT, HI, IA, KY, LA, NJ, NM, UT, and WA). Pathologists who had interpreted melanocytic lesions in the past year were surveyed in this cross-sectional study. The survey included questions on pathologists’ experience, WSI practice patterns and perceptions using a 6-point Likert scale. Agreement was summarized with descriptive statistics to characterize pathologists’ use and perceptions of WSI. The majority of participating pathologists were between 40 and 59 years of age (62 %) and not affiliated with an academic medical center (71 %). Use of WSI was seen more often among dermatopathologists and participants affiliated with an academic medical center. Experience with WSI was reported by 41 %, with the most common type of use being for education and testing (CME, board exams, and teaching in general, 71 %), and clinical use at tumor boards and conferences (44 %). Most respondents (77 %) agreed that accurate diagnoses can be made with this technology, and 59 % agreed that benefits of WSI outweigh concerns. However, 78 % of pathologists reported that digital slides are too slow for routine clinical interpretation. The respondents were equally split as to whether they would like to adopt WSI (49 %) or not (51 %). The majority of pathologists who interpret melanocytic lesions do not use WSI, but among pathologists who do, use is largely for CME, licensure/board exams, and teaching. Positive perceptions regarding WSI slightly outweigh negative perceptions. Understanding practice patterns with WSI as dissemination advances may facilitate concordance of perceptions with adoption of the technology.

Keywords: Digital whole slide imaging, Melanocytic lesions, Dermatopathology

Introduction

Digital whole slide imaging—also referred to as “virtual microscopy” is a technology meant to simulate use of the light microscope through digitization of glass slides to create high resolution images for viewing. Since the introduction of digital whole slide imaging (WSI) almost 15 years ago, the technology has advanced considerably, allowing a range of common applications to proliferate, including education, tumor boards, consultation, research, archiving, and quality assurance testing. WSI is still limited for routine primary diagnostic use due to both technical/logistical and regulatory barriers [1]. Some of the technical and logistical barriers include suboptimal visualization for thick smears and three-dimensional cell clusters [2, 3], inefficient throughput [4], cost of infrastructure, software integration, and cumbersome viewing [5]. The regulatory environment currently restricts use of WSI for primary diagnosis based on a 2011 US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulation as a class III medical device, which requires further evidence to ensure safety and effectiveness [6].

Given the rapid dissemination of digital technology in the broader world, including other fields of medicine, the likelihood of demand for WSI rising in the field of dermatopathology is strong [4, 5, 7], with the expectation that eventually WSI will increase workflow efficiency, with the continual evolution of features to enhance viewing. For example, image viewers can show multiple images at a time, such as an overview image next to a high-powered image [5], and can allow multiple viewers from different locations to examine the same slide at the same time [8]. Also, WSI has the potential to improve accuracy and timeliness of diagnosis, particularly in subspecialty fields such as dermatopathology in which access to experts is limited and telepathology can play an important role [4]. Research evidence is mounting considering virtual microscopy a useful tool for dermatopathology with respect to educational workshops, learning and testing [7, 9–12] and second opinion consultation practices [13–15].

Despite barriers to further adoption, several digital pathology vendors are currently seeking approval from the FDA to use WSI in primary diagnosis [5]. Recent studies have examined the role of WSI in dermatopathology for validity of using WSI for primary diagnosis [5] and for workflow efficiency [4] with somewhat conflicting conclusions. Al-Janabi et al. tested the concordance of skin biopsy and resections (N = 100) of diagnoses made with light microscopy compared to those made on the same slides which were digitally scanned [5]. They found WSI diagnoses to be concordant in 94 % of the cases and slightly discordant in the remaining 6 %, with no discordant cases having clinical or prognostic implications. Their findings were consistent with others, suggesting acceptability of virtual slides compared to glass slides for primary diagnosis [9, 10, 16]. Another study, however, compared time spent per slide between light microscopy and WSI and found the interpretive time was an average of 11 s faster with the microscope than with WSI (23 v. 34 s, respectively) [4]. Also, pathologists report that interpretation of mitotic figures, neutrophil lobules, and eosinophil granules is difficult with digital slides [4]. Given the importance of assessing the mitotic rate for T1 melanoma classification [17, 18], the utility of virtual microscopy for primary diagnosis may be limited.

Understanding the accuracy and workflow patterns associated with WSI in dermatopathology is important in guiding and enhancing its potential in routine practice. Similarly, understanding pathologists’ attitudes and perceptions about use of WSI can facilitate the most usable and clinically sound applications of WSI in dermatopathology. There is very little known about patterns of use among pathologists and their perceptions of digital WSI for dermatopathology interpretation, and data indicating the acceptance of this new emerging technology by practicing dermatopathologists is lacking. This study characterizes use of WSI among a national sample of physicians who interpret melanocytic lesions and examines their perceptions of this digital pathology technology overall and by physician characteristics.

Methods

We conducted a study to assess the variation in and determinants of pathologists’ diagnoses of melanocytic lesions. Study procedures for participating pathologists included completing an online baseline survey and an online histology form to record diagnoses and recommend treatment of a test set of melanocytic lesions. All procedures were HIPAA compliant, and approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Washington, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Oregon Health & Sciences University, Rhode Island Hospital, and Dartmouth College.

We identified potential pathologist participants from community and university laboratories/practices in several geographically-diverse states, including CA, CT, HI, IA, KY, LA, NJ, NM, UT, and WA. A list of 864 potential participants was generated using Internet and professional organizations and updated through telephone calls and Internet searches. Between July 2013 and August 2014, we invited the pathologists to enroll by email (maximum of two attempts), followed by postal mail and telephone calls to non-responders. To compare clinical and demographic characteristics among participants and non-participants, information was obtained on the entire list of invitees from Direct Medical Data, LLC [19].

Eligible participants were those who had completed their pathology training (residency and/or fellowship), interpreted melanocytic skin biopsies within the previous year, and expected to continue interpreting melanocytic skin lesions for the next 2 years while working in the same state.

Data Collection Procedures and Materials

Participation in the study involved completing an online informed consent and survey. Pathologists were invited to complete an optional online CME at completion of this study.

Survey content was developed in consultation with a panel of dermatopathologists and dermatologists (RB, DE, MP, SK, MW). Early survey versions were extensively pilot-tested. Using a cognitive interviewing approach [20, 21], the survey was field-tested by selected community dermatopathologists using a “think aloud” method. The piloters’ comments and impressions were recorded by the research staff and used to refine the survey instrument. The penultimate survey was field-tested for face validity by additional community dermatopathologists. Clinicians involved in survey development and piloting were ineligible for participation in the main study. The final survey queried participating pathologists for general professional information (demographics, training, and clinical practice) and collected data on their opinions and clinical practice regarding melanocytic skin lesions, including use and perceptions of digitized WSI. A full copy of the survey can be reviewed online [22].

Results

Of the 864 potential participants, 450 pathologists or their staff responded. Of the 450 pathologists, 110 were not eligible, 39 declined but their eligibility status was unknown, and 301 confirmed they were eligible to participate, of whom 207 (68.8 %) actively enrolled in the study (Fig. 1). Using t test and chi-square tests, we found no statistically significant differences in mean age, level of direct medical care, or proportion working in a population of ≥250,000 between responders and non-responders, or between eligible pathologists who participated or declined (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Recruitment flowchart of invited M-Path study pathologists

The majority of our final cohort was ages 40–59 years (62 %), male (59 %), and unaffiliated with an academic medical center (72 %) (Table 1). Most reported completion of fellowship training (83 %), including dermatopathology (37 %) than surgical pathology (27 %) (Table 1). Board certification or fellowship training in dermatopathology was common (39 %), and 61 % of participating pathologists reported 10 or more years of interpreting melanocytic lesions. Nearly one half (43 %) reported that they are considered by their peers to be an expert in interpreting these melanocytic lesions (Table 1). Use of digital WSI was reported among 41 % of the study participants and was seen more often among dermatopathologists and participants affiliated with an academic medical center (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of study pathologists (N = 207) with and without use of digital whole slide imaging (WSI) for pathology interpretation

| Participant characteristics | Overall n (col %) | Use of WSI n (col %) | No use of WSI n (col %) | P valuec |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 207 (100) | 84 (41) | 123 (59) | |

| Demographics | ||||

| Age (yrs.) | 0.90 | |||

| <40 | 36 (17) | 14 (17) | 22 (18) | |

| 40–49 | 59 (29) | 24 (29) | 35 (28) | |

| 50–59 | 71 (34) | 31 (37) | 40 (33) | |

| ≥60 | 41 (20) | 15 (18) | 26 (21) | |

| Gender | 0.79 | |||

| Female | 84 (41) | 35 (42) | 49 (40) | |

| Male | 123 (59) | 49 (58) | 74 (60) | |

| Training and experience | ||||

| Affiliation with academic medical center | 0.22 | |||

| No | 148 (71) | 55 (65) | 93 (76) | |

| Yes, adjunct/affiliated | 38 (18) | 20 (24) | 18 (15) | |

| Yes, primary appointment | 21 (10) | 9 (11) | 12 (10) | |

| Residency | 0.38 | |||

| Anatomic/clinical pathology | 186 (90) | 73 (87) | 113 (92) | |

| Dermatology | 17 (8) | 8 (10) | 9 (7) | |

| Both dermatology and anatomic/clinical pathology | 4 (2) | 3 (4) | 1 (1) | |

| Training | 0.075 | |||

| Board certified or fellowship trained in dermatopathologya | 81 (39) | 39 (46) | 42 (34) | |

| Other board certification or fellowship trainingb | 126 (61) | 45 (54) | 81 (66) | |

| Years interpreting melanocytic skin lesions | 0.62 | |||

| <5 | 33 (16) | 13 (15) | 20 (16) | |

| 5–9 | 47 (23) | 23 (27) | 24 (20) | |

| 10–19 | 63 (30) | 24 (29) | 39 (32) | |

| ≥20 | 64 (31) | 24 (29) | 40 (33) | |

| Percent of caseload interpreting melanocytic skin lesions (%) | 0.41 | |||

| <10 | 90 (43) | 33 (39) | 57 (46) | |

| 10–24 | 79 (38) | 36 (43) | 43 (35) | |

| 25–49 | 29 (14) | 13 (15) | 16 (13) | |

| ≥50 | 9 (4) | 2 (2) | 7 (6) | |

| Considered an expert in melanocytic skin lesions by colleagues | 0.22 | |||

| No | 119 (57) | 44 (52) | 75 (61) | |

| Yes | 88 (43) | 40 (48) | 48 (39) | |

Percentages might not add up to 100 due to rounding

aThis category consists of physicians with single or multiple fellowships that include dermatopathology. Also includes physicians with single or multiple board certifications that include dermatopathology

b“Other” includes fellowships or board certifications in surgical pathology, cytopathology, hematopathology, etc.

cChi-square or Fisher’s exact test

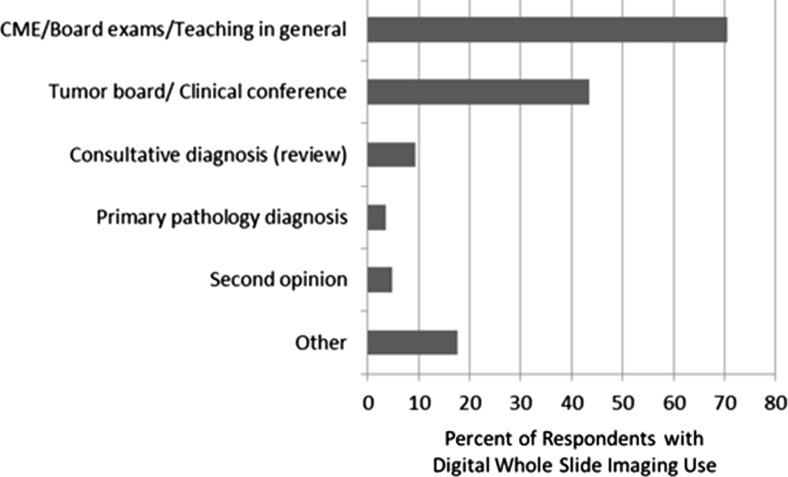

For those reporting use of WSI, the most common reason was for CME, board exams, and teaching (71 %), in addition to use at tumor boards and clinical conferences were also common (44 %) (Fig. 2). Few pathologists reported using digital WSI for provision of consultative diagnosis/review (9 %), or second opinions (5 %) (Fig. 2). Almost 20 % of pathologists using digital WSI used it for other purposes than those listed, such as for tumor marker testing of breast specimens and immunohistochemistry (IHC).

Fig. 2.

Types of use of digital whole slide imaging among the 84 of 207 study pathologists reporting previous use; users could indicate more than one category

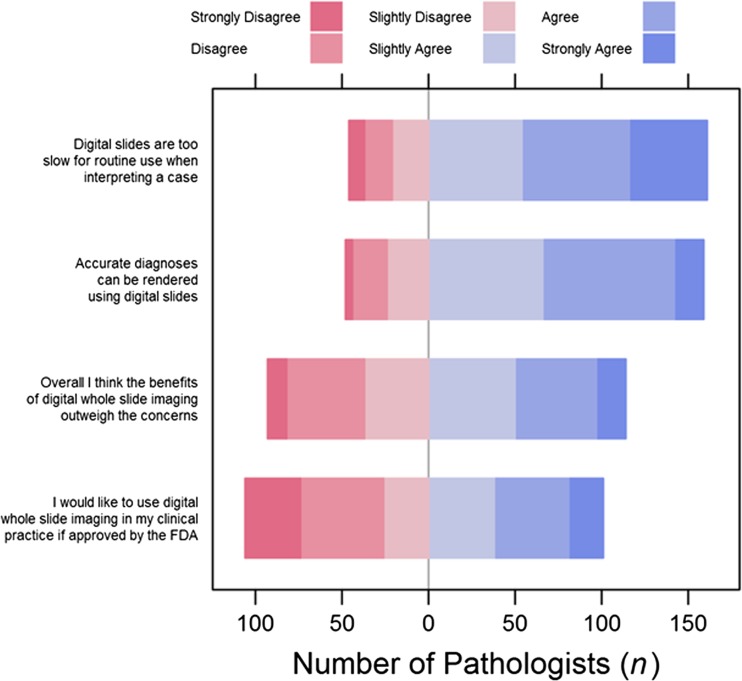

Most participants agreed that accurate diagnoses can be made with digital WSI (77 %) (Fig. 3). However, 77 % of pathologists believed that digital slides are too slow for routine initial clinical interpretation. When asked if the benefits of digital WSI outweigh the concerns, 56 % agreed and 49 % reported that they would like to adopt digital WSI into their practices. Agreement or disagreement with the perception statements did not vary significantly by pathologists’ characteristics or by use v. non-use of WSI (Appendices 1, 2 and 3).

Fig. 3.

Pathologists’ (N = 207) perceptions of digital whole slide imaging for interpretation of melanocytic lesions

Discussion

This study provides the first assessment of how pathologists who interpret melanocytic lesions are using digital WSI, and what their perceptions of this technology are. In our national sample, fewer than half of pathologists who interpret melanocytic lesions use digital WSI for some purpose. Of those who do use it, the vast majority is for educational purposes, with almost half using it for tumor boards or conferences, and very little use for second opinions, or consultations. Aside from the FDA regulations blocking use of digital WSI for primary diagnosis, our findings suggest that the limited use of digital WSI in this sample may also be due, at least in part, to the perception that use of this technology is too slow for routine clinical practice. Diagnostic accuracy with digital WSI did not seem to be a major concern for the study pathologists. A slight majority of pathologists agreed that the benefits of digital WSI outweigh the concerns, but just under half agreed that they would like to use it in their clinical practice if approved by the FDA. This study suggests that speed of interpretation with this technology may be a barrier to increased use, or broader types of use.

Most pathologists in this study agreed that accurate diagnoses can be rendered with digital WSI, which suggests that concerns raised by some pathologists about digital WSI use in routine pathology practice, particularly for melanocytic lesions, while still notable, may be declining. Specifically, in dermatopathology, a concern has been raised that digital WSI may not sufficiently allow identification of mitotic figures—a crucial feature for the diagnostic evaluation of many melanocytic lesions, for the accurate assessment of mitotic rate as a prognostic factor in melanoma, and for the staging of thin melanomas [23]. Accurate interpretation of mitotic rate is vital to appropriate T1 melanoma classification [17, 18]. More broadly, interpretive accuracy using digital WSI is currently contingent upon image quality, the type of platform utilized, user experience, and evidence for concordance of digital WSI interpretation to that of glass slides [24–26].

However, recent research suggests that agreement in histopathologic interpretation between digital WSI and glass slides may support the use of WSI [27–29], including a study of 251 surgical pathology cases that demonstrated a 96 % (95 % CI 94.8–98.3 %) concordance between digital WSI and light microscopy [29]. Another study of intra-observer variability with conventional microscopy compared to digital WSI for interpretation of breast biopsy specimens found comparable intra-observer agreement [30]. The degree to which accuracy of digital WSI versus glass slide interpretation varies by tissue specimen type is unknown. The Digital Pathology Association has called for a three-tiered approach to validating comparability between digital image and light microscopy evaluation, specifically: (1) including a sufficiently extensive representation of all primary organ systems, tissue types, and their cellular elements, (2) ensuring that the basic pathologic processes can be identified in digital WSI, and (c) confirming that key histological changes seen with light microscopy studies can be identified in digital WSI [31].

The concern reported by our study pathologists about the slowness of using WSI mirrors that reported in a prior similar study on breast pathology [32], suggesting that improved tools for image-viewing browsers may help adoption of digital WSI. Digital WSI viewing typically is aided by tools for navigation, annotation, and recording regions of interest, but often still requires substantial time to view the complete slide [1]. Drawbacks, such as slowness and limitations in accuracy may be actual and/or perceived, but need to be understood to most effectively guide improvements and adoption of WSI into clinical practice and shifts in the regulatory environment.

Little is currently known about pathologists’ use and perceptions of digital WSI in the USA, both overall and by clinical specialty [33]. However, in our earlier work focused on digital WSI use among breast pathologists, we found very similar use patterns, with about half reporting use of WSI, largely for CME, board exams, and teaching [32]. Perception responses were also similar, although in that study sample, almost 60 % agreed that the benefits of WSI outweighed the concerns. A major hurdle to full adoption of WSI into routine pathology practice is the FDA restriction on use of WSI for primary diagnosis [6]. Regulatory status in Canada provides a contrast to the USA—with more comprehensive Canadian adoption, including primary diagnosis [32]. Despite that, a Canadian study of pathologists’ perceptions of WSI found the most common uses to be for teaching and consultation [32]. However, Canadian pathologists’ overall use of digital images was higher than in our US study (85 v. 41 %). Further adoption of digital WSI in the USA is likely to occur as evidence for its primary clinical use increases, regulatory statutes evolve, technology advances, and user experience and perceptions adapt.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01 CA151306.

Appendix 1

Table 2.

Characteristics of respondents (N = 207) who agreed with perception statements about digital whole slide imaging

| Participant characteristics | Overall I think the benefits of digital whole slide imaging outweigh the concerns N (row %) agree | P valuec for agree v. disagree | I would like to use digital whole slide imaging in my clinical practice if approved by the FDA N (row %) agree | P valuec for agree v. disagree | Accurate diagnoses can be rendered using digital slides N (row %) agree | P valuec for agree v. disagree | Digital slides are too slow for routine use when interpreting a case N (row %) agree | P valuec for agree v. disagree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 114 (55) | 101 (49) | 159 (77) | 161 (78) | ||||

| Demographics | ||||||||

| Age (yrs.) | 0.67 | 0.49 | 0.32 | 0.56 | ||||

| <40 | 17 (47) | 17 (47) | 24 (67) | 27 (75) | ||||

| 40–49 | 32 (54) | 32 (54) | 44 (75) | 48 (81) | ||||

| 50–59 | 40 (56) | 36 (51) | 58 (82) | 52 (73) | ||||

| ≥60 | 25 (61) | 16 (39) | 33 (80) | 34 (83) | ||||

| Gender | 0.52 | 0.40 | 0.61 | 0.36 | ||||

| Female | 44 (52) | 38 (45) | 63 (75) | 68 (81) | ||||

| Male | 70 (57) | 63 (51) | 96 (78) | 93 (76) | ||||

| Training and experience | ||||||||

| Affiliation with academic medical center | 0.72 | 0.87 | 0.48 | 0.90 | ||||

| No | 79 (53) | 71 (48) | 117 (79) | 114 (77) | ||||

| Yes, adjunct/affiliated | 23 (61) | 20 (53) | 27 (71) | 30 (79) | ||||

| Yes, primary appointment | 12 (57) | 10 (48) | 15 (71) | 17 (81) | ||||

| Residency | >0.99 | 0.85 | 0.010 | 0.72 | ||||

| Anatomic/clinical pathology | 103 (55) | 92 (49) | 148 (80) | 143 (77) | ||||

| Dermatology | 9 (53) | 7 (41) | 8 (47) | 14 (82) | ||||

| Both dermatology and anatomic/clinical pathology | 2 (50) | 2 (50) | 3 (75) | 4 (100) | ||||

| Training | 0.91 | 0.89 | 0.036 | 0.49 | ||||

| Board certified or fellowship trained in dermatopathologya | 45 (56) | 40 (49) | 56 (69) | 61 (75) | ||||

| Other board certification or fellowship trainingb | 69 (55) | 61 (48) | 103 (82) | 100 (79) | ||||

| Years interpreting melanocytic skin lesions | 0.34 | 0.32 | 0.51 | 0.057 | ||||

| <5 | 19 (58) | 21 (64) | 22 (67) | 20 (61) | ||||

| 5–9 | 21 (45) | 21 (45) | 37 (79) | 40 (85) | ||||

| 10–19 | 39 (62) | 29 (46) | 49 (78) | 49 (78) | ||||

| ≥20 | 35 (55) | 30 (47) | 51 (80) | 52 (81) | ||||

| Percent of caseload interpreting melanocytic skin lesions (%) | 0.066 | 0.51 | 0.37 | 0.30 | ||||

| <10 | 42 (47) | 45 (50) | 72 (80) | 73 (81) | ||||

| 10–24 | 47 (59) | 36 (46) | 61 (77) | 62 (78) | ||||

| 25–49 | 21 (72) | 17 (59) | 21 (72) | 21 (72) | ||||

| ≥50 | 4 (44) | 3 (33) | 5 (56) | 5 (56) | ||||

| Considered an expert in melanocytic skin lesions by colleagues | 0.32 | 0.76 | 0.23 | 0.60 | ||||

| No | 62 (52) | 57 (48) | 95 (80) | 91 (76) | ||||

| Yes | 52 (59) | 44 (50) | 64 (73) | 70 (80) | ||||

aThis category consists of physicians with single or multiple fellowships that include dermatopathology. Also includes physicians with single or multiple board certifications that include dermatopathology

b“Other” includes fellowships or board certifications in surgical pathology, cytopathology, hematopathology, etc.

cChi-square or Fisher’s exact test

Appendix 2

Table 3.

Characteristics of respondents (N = 207) who agreed with perception statements about digital whole slide imaging

| Participant characteristics | Overall I think the benefits of digital whole slide imaging outweigh the concerns N (row %) agree | P valuec for agree v. disagree | I would like to use digital whole slide imaging in my clinical practice if approved by the FDA N (row %) agree | P valuec for agree v. disagree | Accurate diagnoses can be rendered using digital slides N (row %) agree | P valuec for agree v. disagree | Digital slides are too slow for routine use when interpreting a case N (row %) agree | P valuec for agree v. disagree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 114 (55) | 101 (49) | 159 (77) | 161 (78) | ||||

| Demographics | ||||||||

| Age (yrs.) | 0.67 | 0.49 | 0.32 | 0.56 | ||||

| <40 | 17 (47) | 17 (47) | 24 (67) | 27 (75) | ||||

| 40–49 | 32 (54) | 32 (54) | 44 (75) | 48 (81) | ||||

| 50–59 | 40 (56) | 36 (51) | 58 (82) | 52 (73) | ||||

| ≥60 | 25 (61) | 16 (39) | 33 (80) | 34 (83) | ||||

| Gender | 0.52 | 0.40 | 0.61 | 0.36 | ||||

| Female | 44 (52) | 38 (45) | 63 (75) | 68 (81) | ||||

| Male | 70 (57) | 63 (51) | 96 (78) | 93 (76) | ||||

| Training and experience | ||||||||

| Affiliation with academic medical center | 0.72 | 0.87 | 0.48 | 0.90 | ||||

| No | 79 (53) | 71 (48) | 117 (79) | 114 (77) | ||||

| Yes, adjunct/affiliated | 23 (61) | 20 (53) | 27 (71) | 30 (79) | ||||

| Yes, primary appointment | 12 (57) | 10 (48) | 15 (71) | 17 (81) | ||||

| Residency | >0.99 | 0.85 | 0.010 | 0.72 | ||||

| Anatomic/clinical pathology | 103 (55) | 92 (49) | 148 (80) | 143 (77) | ||||

| Dermatology | 9 (53) | 7 (41) | 8 (47) | 14 (82) | ||||

| Both dermatology and anatomic/clinical pathology | 2 (50) | 2 (50) | 3 (75) | 4 (100) | ||||

| Training | 0.91 | 0.89 | 0.036 | 0.49 | ||||

| Board certified or fellowship trained in dermatopathologya | 45 (56) | 40 (49) | 56 (69) | 61 (75) | ||||

| Other board certification or fellowship trainingb | 69 (55) | 61 (48) | 103 (82) | 100 (79) | ||||

| Years interpreting melanocytic skin lesions | 0.34 | 0.32 | 0.51 | 0.057 | ||||

| <5 | 19 (58) | 21 (64) | 22 (67) | 20 (61) | ||||

| 5–9 | 21 (45) | 21 (45) | 37 (79) | 40 (85) | ||||

| 10–19 | 39 (62) | 29 (46) | 49 (78) | 49 (78) | ||||

| ≥20 | 35 (55) | 30 (47) | 51 (80) | 52 (81) | ||||

| Percent of caseload interpreting melanocytic skin lesions (%) | 0.066 | 0.51 | 0.37 | 0.30 | ||||

| <10 | 42 (47) | 45 (50) | 72 (80) | 73 (81) | ||||

| 10–24 | 47 (59) | 36 (46) | 61 (77) | 62 (78) | ||||

| 25–49 | 21 (72) | 17 (59) | 21 (72) | 21 (72) | ||||

| ≥50 | 4 (44) | 3 (33) | 5 (56) | 5 (56) | ||||

| Considered an expert in melanocytic skin lesions by colleagues | 0.32 | 0.76 | 0.23 | 0.60 | ||||

| No | 62 (52) | 57 (48) | 95 (80) | 91 (76) | ||||

| Yes | 52 (59) | 44 (50) | 64 (73) | 70 (80) | ||||

aThis category consists of physicians with single or multiple fellowships that include dermatopathology. Also includes physicians with single or multiple board certifications that include dermatopathology

b“Other” includes fellowships or board certifications in surgical pathology, cytopathology, hematopathology, etc.

cChi-square or Fisher’s exact test

Appendix 3

Table 4.

Characteristics of respondents (N = 159) who agreed that accurate diagnoses can be rendered using digital slides

| Participant characteristics | Total | Overall I think the benefits of digital whole slide imaging outweigh the concerns N (row %) agree | P valuec | I would like to use digital whole slide imaging in my clinical practice if approved by the FDA N (row %) agree | P valuec | Digital slides are too slow for routine use when interpreting a case N (row %) agree | P valuec | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (col %) | Use of WSI | No use of WSI | Use of WSI | No use of WSI | Use of WSI | No use of WSI | ||||

| Total | 159 (100) | 48 (67) | 60 (69) | 42 (58) | 54 (62) | 51 (71) | 67 (77) | |||

| Demographics | ||||||||||

| Age (yrs.) | 0.24 | 0.91 | 0.18 | |||||||

| <40 | 24 (15) | 8 (67) | 8 (67) | 8 (67) | 7 (58) | 8 (67) | 8 (67) | |||

| 40–49 | 44 (28) | 9 (50) | 20 (77) | 12 (67) | 18 (69) | 15 (83) | 19 (73) | |||

| 50–59 | 58 (36) | 20 (71) | 20 (67) | 16 (57) | 19 (63) | 16 (57) | 25 (83) | |||

| ≥60 | 33 (21) | 11 (79) | 12 (63) | 6 (43) | 10 (53) | 12 (86) | 15 (79) | |||

| Gender | 0.016 | 0.096 | 0.17 | |||||||

| Female | 63 (40) | 15 (52) | 26 (76) | 13 (45) | 22 (65) | 23 (79) | 25 (74) | |||

| Male | 96 (60) | 33 (77) | 34 (64) | 29 (67) | 32 (60) | 28 (65) | 42 (79) | |||

| Training and experience | ||||||||||

| Affiliation with academic medical center | 0.24 | 0.65 | 0.66 | |||||||

| No | 117 (74) | 27 (59) | 49 (69) | 25 (54) | 43 (61) | 31 (67) | 54 (76) | |||

| Yes, adjunct/affiliated | 27 (17) | 15 (79) | 7 (88) | 13 (68) | 7 (88) | 14 (74) | 7 (88) | |||

| Yes, primary appointment | 15 (9) | 6 (86) | 4 (50) | 4 (57) | 4 (50) | 6 (86) | 6 (75) | |||

| Residency | – | 0.53 | 0.63 | |||||||

| Anatomic/clinical pathology | 148 (93) | 43 (66) | 56 (67) | 38 (58) | 51 (61) | 46 (71) | 64 (77) | |||

| Dermatology | 8 (5) | 3 (75) | 4 (100) | 2 (50) | 3 (75) | 2 (50) | 3 (75) | |||

| Both dermatology and anatomic/clinical pathology | 3 (2) | 2 (67) | . (.) | 2 (67) | . (.) | 3 (100) | . (.) | |||

| Training | 0.85 | 0.90 | 0.87 | |||||||

| Board certified or fellowship trained in dermatopathologya | 56 (35) | 22 (71) | 19 (76) | 20 (65) | 17 (68) | 21 (68) | 18 (72) | |||

| Other board certification or fellowship trainingb | 103 (65) | 26 (63) | 41 (66) | 22 (54) | 37 (60) | 30 (73) | 49 (79) | |||

| Years interpreting melanocytic skin lesions | 0.82 | 0.97 | 0.087 | |||||||

| <5 | 22 (14) | 8 (80) | 10 (83) | 8 (80) | 10 (83) | 5 (50) | 4 (33) | |||

| 5–9 | 37 (23) | 10 (53) | 11 (61) | 10 (53) | 10 (56) | 17 (89) | 14 (78) | |||

| 10–19 | 49 (31) | 14 (70) | 22 (76) | 12 (60) | 17 (59) | 12 (60) | 26 (90) | |||

| ≥20 | 51 (32) | 16 (70) | 17 (61) | 12 (52) | 17 (61) | 17 (74) | 23 (82) | |||

| Percent of caseload interpreting melanocytic skin lesions (%) | 0.79 | 0.17 | 0.32 | |||||||

| <10 | 72 (45) | 17 (57) | 24 (57) | 19 (63) | 23 (55) | 21 (70) | 35 (83) | |||

| 10–24 | 61 (38) | 20 (67) | 24 (77) | 13 (43) | 21 (68) | 22 (73) | 22 (71) | |||

| 25–49 | 21 (13) | 9 (90) | 10 (91) | 8 (80) | 9 (82) | 8 (80) | 7 (64) | |||

| ≥50 | 5 (3) | 2 (100) | 2 (67) | 2 (100) | 1 (33) | 0 (0) | 3 (100) | |||

| Considered an expert in melanocytic skin lesions by colleagues | 0.59 | 0.76 | 0.57 | |||||||

| No | 95 (60) | 23 (59) | 37 (66) | 22 (56) | 33 (59) | 28 (72) | 42 (75) | |||

| Yes | 64 (40) | 25 (76) | 23 (74) | 20 (61) | 21 (68) | 23 (70) | 25 (81) | |||

aThis category consists of physicians with single or multiple fellowships that include dermatopathology. Also includes physicians with single or multiple board certifications that include dermatopathology

b“Other” includes fellowships or board certifications in surgical pathology, cytopathology, hematopathology, etc.

cType III test for the 3-way association

Contributor Information

Tracy Onega, Phone: 603-653-3671, Email: Tracy.L.Onega@dartmouth.edu.

Lisa M. Reisch, Email: lreisch@u.washington.edu

Paul D. Frederick, Email: PaulFred@u.washington.ed

Berta M. Geller, Email: Berta.Geller@uvm.edu

Heidi D. Nelson, Email: Nelsonh@ohsu.edu

Jason P. Lott, Email: Jason.Lott@Yale.edu

Andrea C. Radick, Email: radica@uw.edu

David E. Elder, Email: David.Elder@uphs.upenn.edu

Raymond L. Barnhill, Email: raymond.barnhill@curie.fr

Joann G. Elmore, Email: jelmore@u.washington.edu

References

- 1.Pantanowitz L, Valenstein PN, Evans AJ, et al. Review of the current state of whole slide imaging in pathology. J Pathol Inform. 2011;2:36. doi: 10.4103/2153-3539.83746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pantowitz L, Hornish M, Goulart RA. The impact of digital imaging in the field of cytopathology. Cytojournal. 2009;6:6. doi: 10.4103/1742-6413.48606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilbur DC. Digital cytology: current state of the art and prospects for the future. Acta Cytol. 2011;55:227–238. doi: 10.1159/000324734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Velez N, Jukic D, Ho J. Evaluation of two whole-slide imaging applications in dermatopathology. Hum Pathol. 2008;39:1341–1349. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al-Janabi S, Huisman A, Vink A, Leguit J, Offerhaus GJA, ten Kate JFW, van Dijk R, van Diest PJ. Whole slide images for primary diagnostics in dermatopathology: a feasibility study. J Clin Pathol. 2012;65:152–158. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2011-200277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/DeviceRegulationandGuidance/Overview/ClassifyYourDevice/. Accessed 20 Oct 2014

- 7.Brick KE, Comfere NI, Broeren MD, Gibson LE, Wieland CN. The application of virtual microscopy in a dermatopathology educational setting: assessment of attitudes among dermatopathologists. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:224–227. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leong FJ, McGee JO. Automated complete slide digitization: a medium for simultaneous viewing by multiple pathologists. J Pathol. 2001;195:508–514. doi: 10.1002/path.972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mooney E, Hood AF, Lampros J, et al. Comparative diagnostic accuracy in virtual dermatopathology. Skin Res Technol. 2011;17:251–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0846.2010.00493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mooney E, Kempf W, Jemec GBE, Koch L, Hood A. Diagnostic accuracy in virtual dermatopathology. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:758–761. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2012.01931.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bruch LA, De Young BR, Kreiter CD, et al. Competency assessment of residents in surgical pathology using virtual microscopy. Hum Pathol. 2009;40:1122–1128. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brick KE, Sluzevich JC, Cappel MA, et al: Comparison of virtual microscopy and glass slide microscopy during a simulated in-training examination. American Society of Dermatopathology 49th Annua Meeting, October 11–14, 2012, Chicago, IL

- 13.Leinweber B, Massone C, Kodama K, et al. Teledermatopathology: a controlled study about diagnostic validity and technical requirements for digital transmission. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:413–416. doi: 10.1097/01.dad.0000211523.95552.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zembowicz A, Ahmad A, Lyle SR. A comprehensive analysis of a web-based dermatopathology second opinion consultation practice. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:379–383. doi: 10.5858/2010-0187-OA.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okada DH, Binder SW, Felten CL, Strauss JS, Marchevsky AM. “Virtual microscopy” and the internet as telepathology consultation tools: diagnostic accuracy in evaluating melanocytic skin lesions. Am J Dermatopathol. 1999;21:525. doi: 10.1097/00000372-199912000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koch LH, Lampros JN, Delong LK, et al. Randomized comparison of virtual microscopy and traditional glass microscopy in diagnostic accuracy among dermatology and pathology residents. Hum Pathol. 2009;40:662–667. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wong SL, Balch CM, Hurley P, Agarwala SS, Akhurst TJ, Cochran A, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for melanoma: American Society of Clinical Oncology and Society of Surgical Oncology joint clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(23):2912–2918. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.3519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wong SL, Balch CM, Hurley P, Agarwala SS, Akhurst TJ, Cochran A, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for melanoma: American Society of Clinical Oncology and Society of Surgical Oncology joint clinical practice guideline. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19(11):3313–3324. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2475-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Direct Medical Data, LLC. http://www.dmddata.com/data_lists_physicians.asp. Accessed 1 Jun 2015

- 20.Willis, Gordon B: Cognitive Interviewing: A “How To” Guide. In Meeting of the American Statistical Association. 1999

- 21.Cornish TC, Swapp RE, Kaplan KJ. Whole-slide imaging: routine pathologic diagnosis. Adv Anat Pathol. 2012;19:152–159. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0b013e318253459e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elmore JG. Accuracy in the diagnosis of melanoma and the impact of double reading. Baseline Survey. http://sph.washington.edu/faculty/fac_bio.asp?url_ID=Elmore_Joann. 2015. Accessed 1 Jun 2015

- 23.Ghaznavi F, Evans A, Madabhushni A, Feldman M. Digital imaging in pathology: whole-slide imaging and beyond. Annu Rev Pathol Mech Dis. 2013;8:331–359. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011811-120902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Henricks WH. Evaluation of whole slide imaging for routine surgical pathology: looking through a broader scope. J Pathol Inform. 2012;3:39. doi: 10.4103/2153-3539.103009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cerroni L, Barnhill R, Elder D, Gottlieb G, Heenan P, Kutzner H, LeBoit PE, Mihm M, Jr., Rosai J, Kerl H: Melanocytic tumors of uncertain malignant potential (MELTUMPs): Results of a Tutorial held at the XXIX Symposium of the International Society of Dermatopathology in Graz, October 2008. Am J Surg Pathol 34(3):314–326, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Hashimoto N, Bautista PA, Yamaguchi M, Ohyama N, Yagi Y. Referenceless image quality evaluation for whole slide imaging. J Pathol Inform. 2012;3:9. doi: 10.4103/2153-3539.93891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ho J, Parwani AV, Jukic CM, et al. Use of whole slide imaging in surgical pathology quality assurance: design and pilot validation studies. Hum Pathol. 2006;37:322–331. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Campbell WS, Lele SM, West WW, Lazenby AJ, Smith LM, Hinrichs SH. Concordance between whole-slide imaging and light microscopy for routine surgical pathology. Hum Pathol. 2012;43:1739–1744. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2011.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reyes C, Ikpatt OF, Nadji M, Cote RJ: Intra-observer reproducibility of whole slide imaging for the primary diagnosis of breast needle biopsies. J Pathol Inform 1–5, 2014. 10.4103/2153-3539.127814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Cann J, Chlipala E, Ellin J, Kawano Y, Knight B, Long RE, Lowe A, Machotka SV, Smith A: Validation of digital pathology systems in the regulated nonclinical environment. Digital Pathology Association white paper. 2011, https://digitalpathologyassociation.org/white-papers_1 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Onega T, Weaver D, Geller B, Oster N, Tosteson ANA, Carney PA, Nelson H, Allison KH, Elmore JE. Digitized whole slides for breast pathology interpretation: current practices and perceptions. J Digit Imaging. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s10278-014-9683-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mea VD, Demichelis F, Viel F, Palma PD, Betlrami CA. User attitudes in analyzing digital slides in a quality control test bed: a preliminary study. Comput Methods Prog Biomed. 2006;82:177–186. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2006.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bellis M, Metias S, Naugler C, Pollett A, Jothy S, Yousef GM. Digital pathology: attitudes and practices in the Canadian pathology community. J Pathol Inform. 2013;4:3. doi: 10.4103/2153-3539.108540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]