Abstract

Dating aggression is a prevalent and costly public health concern. Using a relational risk framework, this study examined acute and chronic relational risk factors (negative interactions, jealousy, support, & relationship satisfaction) and their effects on physical and psychological dating aggression. The study also examined the interaction between chronic and acute risk, allowing us to assess how changes in acute risk have differing effects depending on whether the individual is typically at higher chronic risk. A sample of 200 youth (100 female) completed seven waves of data, which spanned nine years from middle adolescence to young adulthood (M age at Wave 1 = 15.83). Using hierarchical linear modeling, analyses revealed both acute (within-person) and chronic (between-person) levels in jealousy, negative interactions, and relationship satisfaction, were associated with physical and psychological dating aggression. Significant interactions between chronic and acute risk emerged in predicting physical aggression for negative interactions, jealousy, and relationship satisfaction such that those with higher levels of chronic risk are more vulnerable to increases in acute risk. These interactions between chronic and acute risk indicate that risk is not static, and dating aggression is particularly likely to occur at certain times for youth at high risk for dating aggression. Such periods of increased risk may provide opportunities for interventions to be particularly effective in preventing dating aggression or its consequences. Taken together, these findings provide support for the role of relational risk factors for dating aggression. They also underscore the importance of considering risk dynamically.

Introduction

Dating aggression has been identified as a serious public health concern among adults and, increasingly, adolescents (Breiding, Chen, & Black, 2014). Consequently, significant attention has been paid to identifying risk factors for dating aggression among adolescents and young adults (Capaldi, Knoble, Shortt, & Kim, 2012). Although much research has been done, the literature has been critiqued for often being atheoretical (Shorey, Cornelius, & Bell, 2008), focusing primarily on individual risk factors, and not sufficiently considering relational risk factors (i.e., the characteristics of the relationship, such as satisfaction) (Reese-Weber & Johnson, 2013). Relational risk factors are theorized to increase risk for aggression by intensifying the frequency and severity of conflict situations (Riggs & O’Leary, 1989). Indeed, research suggests that relational risk factors may be more predictive of dating aggression than commonly studied factors such as alcohol use (Foran & O’Leary, 2008) or psychopathology (Capaldi et al., 2012).

In response to these criticisms, Reese-Weber and Johnson (2013) extended Riggs and O’Leary’s (1989) background-situational theory to further emphasize relationship risk factors. In their original theory, Riggs and O’Leary conceptualized risk factors as fitting into two components: background risk factors and situational risk factors. Background risk factors are features that an individual may be bringing to a relationship, such as individual psychopathology. In contrast, situational risk factors are specific to the context of dating aggression, such as stress, alcohol use, and relational risk factors. Reese-Weber and Johnson (2013) contended that relational risk factors warrant increased attention, on par with other sets of risk factors. Therefore, Reese-Weber and Johnson argued that relational risk factors should be separated from situational risk factors to emphasize their critical role in the etiology of dating aggression. Instead, they proposed an extension to Rigg’s and O’Leary’s theory of dating aggression such that risk factors are organized into three components: background risk factors (e.g., individual psychopathology), immediate situational risk factors (e.g., stress levels), and relational risk factors (e.g., relationship satisfaction). In the present article, we refer to this theoretical extension as a relational risk framework.

The present longitudinal study aimed to contribute to a relational risk framework by longitudinally examining relational risk factors that have been identified as theoretically and empirically linked to dating aggression. Specifically, we examined negative interactions, jealousy, support, and relationship satisfaction. Negative interactions have received the most attention as a relational risk factor for dating aggression. It has been shown to be a consistent predictor of dating aggression (O’Keefe, 2005), and is thought to be the most proximal relational risk factor preceding aggression (Riggs & O’Leary, 1989). Similarly, jealousy and relationship satisfaction are theorized to contribute to risk by exacerbating hostile patterns of communication, which may then escalate into dating aggression. Indeed, each has been empirically linked to greater risk for dating aggression as well (O’Leary & Slep, 2003; Kaura & Lohman, 2007), although little work has examined them longitudinally (Vagi, Rothman, Latzman, Tharp, Hall, & Breiding, 2013). Theoretically, support may also be expected to function as a protective factor for dating aggression, as it reflects a stronger bond and positivity in the relationship (Riggs & O’Leary, 1989). Empirical support for this idea is limited, however, as support behavior has been associated with no differences in risk for aggression (Marcus & Swett, 2002) or greater dating aggression risk (Giordano, Soto, Manning, & Longmore, 2010). Thus, theoretically and empirically, negative interactions, jealousy, relationship satisfaction, and support may all be important relational factors that increase risk dating aggression.

The current study also examined both psychological aggression and physical aggression, as psychological aggression is also associated with psychological consequences (Lawrence, Orengo-Aguayo, Langer, & Brock, 2012), and is often a precursor to physical aggression (O’Leary & Maiuro, 2001). Finally, consistent with prior work on ecological models of aggression, we used an involvement model of dating aggression, which included victimization, perpetration, and mutual aggression (Connolly, Friedlander, Pepler, Craig, & Laporte, 2010; Williams, Connolly, Pepler, Craig, & Laporte, 2008). During this developmental period, victimization and perpetration are highly correlated and most often co-occur (O’Leary & Slep, 2003; Whitaker, Haileyesus, Swahn, & Saltzman, 2007; Williams et al., 2008); thus, it is best to examine them together.

Importantly, a relational risk framework of dating aggression is consistent with the idea that risk for dating aggression is not static, and that individuals may be at higher risk at some times than at other times. For example, if individuals are very jealous regarding a specific partner’s behaviors, they may be at greater risk at that time. We refer to this as acute risk. Moreover, individuals may also have chronic relational risk. For example, some individuals may typically be more jealous than others, placing them at greater risk over the course of time. Finally, if risk is indeed dynamic, we might expect interactions between chronic and acute risk. That is, those who are chronically jealous about their partners may be more likely to be involved in dating aggression when they are acutely jealous than when not; on the other hand, risk for dating aggression may not be particularly elevated at times of acute risk for those who are not chronically jealous. Alternatively, those who are not chronically jealous may be more likely to be involved in dating aggression if they have a partner who elicits greater feelings of jealousy than usual for them, whereas those who are chronically jealous may be at high risk regardless of whether their acute level of jealousy is particularly high for them. Thus, examining acute and chronic risk, as well as the interaction between the two, offers important information regarding when, and for whom, risk for dating aggression increases.

Chronic and Acute Risk

Although they are conceptually critical to the understanding of dating aggression, relatively little work has examined relational risk factors, and findings have been mixed (see Reese-Weber & Johnson, 2013). Existing work has primarily examined associations at one time point, not allowing for an examination of variations in risk across time. To more fully understand the links between relational risk factors and dating aggression, we examined both between-person (chronic risk) and within-person effects (acute risk) (Curran & Bauer, 2011). Between-person effects (chronic risk) refer to whether differences between people on one variable are associated with differences in dating aggression. For example, is a person who has higher levels of jealousy on average at greater risk for dating aggression? In contrast, within-person effects (acute risk) refer to whether variations in relational factors within a person over time are associated with variations in dating aggression over time. For example, if a person has a higher level of jealousy than she typically does, does her risk for dating aggression also increase? Studies of within-person variation are central to many psychological theories, as social scientists are often interested in understanding changes or differences within a person, rather than differences between people per se. For example, developmental psychologists have increasingly relied on longitudinal studies of the same people over time, rather than inferring change rom cross-sectional comparisons of different individuals. Studies of within-person effects can also provide information about when activities occur (vs. who is likely to engage in them). They may also be less prone to spurious associations stemming from third variables because third variables that are relatively stable over time cannot account for variation within a person.

Finally, the current study also examined an interaction between within and between person effects to assess whether the association between acute risk and aggression depends on the level of chronic risk. To our knowledge, no research has examined these interaction effects; evidence of such interactions would highlight potential periods of increased risk and inform more targeted interventions.

Hypotheses

First, consistent with a relational risk framework, we hypothesized that higher levels of negative interactions and jealousy will be associated with more physical and psychological dating aggression. Lower levels of support and relationship satisfaction will be associated with higher levels of physical and psychological dating aggression. Second, acute (within-person) increases in relational risk factors will be associated with acute (within-person) increases for both psychological and physical aggression. Thus, when a person is experiencing higher levels of negative interaction and jealousy than usual or lower levels of support and satisfaction than usual, psychological and physical aggression will be greater. Finally, interactions will occur between acute (within-person) and chronic (between-person) risk for both psychological and physical aggression. We expected the specific nature of these interactions would illustrate one of two patterns. One possibility is that those who are not chronically at risk may show greater levels of aggression at times of acute risk, whereas those at chronic risk may consistently be at greater levels of risk, regardless of acute risk. Alternatively, those with chronic risk may be more vulnerable to changes in acute risk.

Method

Participants

The participants were part of a longitudinal study investigating the role of relationships with parents, peers, and romantic partners on psychosocial adjustment. Two hundred 10th grade high school students (100 boys, 100 girls; M age at Wave 1 = 15 years 10.44 months old, SD = .49) were recruited. The participants came from working class to upper middle class neighborhoods in a large Western metropolitan area. We sought to obtain such a diverse sample by distributing brochures and sending letters to families residing in a number of different zip codes and to students enrolled in various schools in ethnically diverse neighborhoods. We were unable to determine the ascertainment rate because we used brochures and because the letters were sent to many families who did not have a 10th grader. We contacted interested families with the goal of selecting a sample that had an equal number of males and females, and had a distribution of racial/ethnic groups that approximated that of the United States. To insure maximal response, we paid families $25 to hear a description of the project in their homes. Of the families that heard the description, 85.5% expressed interest and carried through with the Wave 1 assessment.

The sample consisted of 11.5% African Americans, 12.5% Hispanics, 1.5% Native Americans, 1% Asian American, 4% biracial, and 69.5% White, non-Hispanics. With regard to family structure, 57.5% were residing with 2 biological or adoptive parents, 11.5% were residing with a biological or adoptive parent and a step parent or partner, and the remaining 31% were residing with a single parent or relative. The sample was of average intelligence (WISC-III vocabulary score M = 9.8, SD = 2.44) comparable to national norms on multiple measures of adjustment (see Furman, Low, & Ho, 2009); 55.4% of their mothers had a college degree, indicating that the sample was predominately middle or upper middle class.

In Wave 1, 59.8% of participants reported having had a romantic partner in the last year; in Wave 2, 66% had a romantic partner; in Wave 3, 78.2% had a romantic partner; in Wave 4, 75.9% had a romantic partner; in Wave 5, 73.5% had a romantic partner; in Wave 6, 79.9% had a romantic partner; in Wave 7, 80.6% had a romantic partner. In Wave 5, 11% of participants were cohabitating with a romantic partner or married; 22% in Wave 6; 32% in Wave 7.

Procedure

Adolescents participated in a series of 2–3 laboratory sessions in which they were interviewed about romantic relationships, completed questionnaires, and observed with a romantic partner (see blinded citation 1 for further information). For the purposes of the current study, we used the questionnaire data from the first through seventh waves of data collection, beginning when the participants were in the 10th grade and ending approximately 5.5 years after graduation from high school. Data were collected on a yearly basis in Waves 1 through 4, and then one and a half years later for Waves 5–7. The seven waves of data were collected between 2000 and 2010. Participant retention was excellent (Wave 1 & 2: N = 200; Wave 3: N = 199, Wave 4: N = 195, Wave 5: N = 186, Wave 6: N = 185, Wave 7: N = 179). There were no differences on the variables of interest between those who did and did not remain in the study.

Participants were compensated between $30 and $75 for completing questionnaires in the various waves of data collection. The study was approved by the local Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Physical and psychological aggression

Dating aggression was assessed with the Conflict Resolution Style Inventory (CRSI; Kurdek, 1994). The CRSI consists of 16 items pertaining to means of handling conflict. Using a 7-point scale, adolescents rated how often they and their partner had each engaged in various behaviors with their most important romantic partner in the past year. The dominance subscale consists of 4-item (e.g., “throwing insults and digs”) and was used as a measure of psychological aggression (M alpha = .84). Four items from the Conflict Tactics Scale (Straus, 1979) were added to assess adolescents’ physical aggression (e.g., “slapping or hitting”) (M alpha = .90). We examined dating aggression in three forms. First, based on an involvement model of dating aggression, we combined ratings of victimization and perpetration. Correlations between psychological victimization and perpetration (M r = .76) and physical victimization and perpetration (M r = .65) supported this conceptualization. We also examined victimization and perpetration separately to further assess the effects.

Support and negative interactions

Participants completed the short version of the Network of Relationships Inventory: Behavioral Systems Version (NRI), to assess their perceptions of their most important romantic relationship in the last year (Furman & Buhrmester, 2009). The NRI included five items regarding social support (e.g., How much do you turn to this person for comfort and support when you are troubled about something?) and six items regarding negative interactions (e.g., How much do you and this person get on each other’s nerves?). Participants rated how much the characteristic occurred using a 5-point scale. Romantic support was derived by averaging the five social support items and negative interaction scores were derived by averaging the six negative interactions items (M alphas = .89 & .92, respectively).

Relationship satisfaction

Relationship satisfaction was measured with a version of the Quality of Marriage Inventory (QMI; Norton, 1983) that was adapted to assess relationship satisfaction among adolescents and young adults. The measure consisted of 5 seven-point Likert items and 1 ten-point Likert item. An example of a question is “My relationship with my boy/girlfriend makes me happy” (M alpha = .97). Scores on items were transformed so that all items had the same range of potential scores; item scores were then averaged to derive a total score.

Jealousy

Jealousy was measured using Pfeiffer and Wong’s (1989) Multidimensional Jealousy Scale (MJS). Participants were asked to complete 24 questions assessing cognitive, emotional, and behavioral jealousy. Participants rated their responses on a five-point Likert scale (1= never to 5 = all the time). An example of an item is: “I question my boy/girlfriend about his or her whereabouts.”.” (M alpha = .91). The 24 items were averaged to derive a total score.

Analytic Strategy

We conducted multilevel models to examine the between-person (chronic) and within-person (acute) effects. Each model had the following form.

| Level 1: | Yi = β0 + β1(age) + β2(relational risk factor)+ β3(relationship presence)+ ri |

| Level 2: | β0 = γ00 + γ01(gender) + γ02(relational risk factor mean) + γ03(relational risk factor mean X gender) |

| β1 = γ10 + γ11(gender) | |

| β2 = γ20 + γ21(gender) + γ22(relational risk factor mean) | |

| β3 = γ30 |

In these models, Y represented psychological/physical aggression reported by individual i. Age was included as a covariate at Level 1 (β1). The within-person (acute) effect was examined at Level 1 by the term relational risk factor (β2). This term was group-mean centered, such that scores reflected the score for that relational risk factor relative to that person’s average score across the seven waves for that relational risk factor. The between-person (chronic) effect was examined at Level 2 by the term relational risk factor mean (γ02). This term was the person’s average score on that relational risk factor across the seven waves and is grand mean centered so as to compare it to other participants’ relationship characteristics. In addition, interactions between the within-person (acute) and between-person (chronic) term were estimated by cross-level interactions (γ22). Finally, gender was included as a Level 2 main effect (γ01), in an interaction with the between-person (chronic) term (γ03), in a cross-level interaction with age (γ11) and in a cross-level interaction with the within-person (acute) term (γ21).

Participants who did not have a relationship during a specific wave were assigned missing values to the relationship characteristics in that wave; multilevel modeling uses full information maximum likelihood (FIML) so that participants who had valid data in some waves were retained. FIML provides a powerful alternative to listwise deletion and protects against bias in analyses (Graham, Olchowski, & Gilreath, 2007; Little, Jorgensen, Lang, & Moore, 2013). Participants who did not have a romantic relationship during the entire period of the study were removed (n = 5). To better meet the assumptions of missing at random (MAR), we included a relationship presence (β3) measure indicating whether the participant was in a relationship in a wave. Three time-varying predictors (support, jealousy, & satisfaction) were correlated with the time variable (age). Therefore, Curran and Bauer’s (2011) procedure for data unbalanced with respect to time was used to disaggregate the within-person and between-person effects of all the independent variables.

Results

Descriptive statistics can be found in Table 1. Univariate growth curve models revealed that jealousy significantly declined (β = −0.02, p = .001), whereas support (β = 0.08, p < .001) and relationship satisfaction (β = 1.47, p = .003) significantly increased over time. Negative interactions, psychological dating aggression involvement, and physical dating aggression involvement did not change over time. To assess between-person and within-person variability, we ran fully unconditional multilevel models. The results indicated that 72% of the variability of psychological dating aggression involvement and 78% of the variability of physical dating aggression involvement were within-person; the remaining proportions of variability were between-person.

Table 1.

Mean Relational Risk Factors and Dating Aggression (with Standard Deviations in Parentheses)

| Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Wave 3 | Wave 4 | Wave 5 | Wave 6 | Wave 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 15.88 (0.47) | 16.89 (0.47) | 17.94 (0.50) | 19.03 (0.56) | 20.51 (0.56) | 22.11 (0.51) | 23.70 (0.61) |

| Negative Interactions | 1.82 (0.75) | 1.71 (0.76) | 1.95 (0.94) | 1.74 (0.79) | 1.88 (0.81) | 1.79 (0.75) | 1.74 (0.61) |

| Jealousy | 2.51 (0.44) | 2.47 (0.45) | 2.53 (0.50) | 2.44 (0.54) | 2.44 (0.81) | 2.42 (0.48) | 2.36 (0.43) |

| Support | 3.07 (1.03) | 3.52 (1.08) | 3.52 (1.05) | 3.73 (1.00) | 3.66 (1.04) | 3.84 (0.98) | 3.93 (0.96) |

| Relationship Satisfaction | 11.34 (4.42) | 12.28 (4.56) | 12.03 (4.81) | 13.63 (4.13) | 12.26 (4.87) | 13.10 (4.64) | 13.18 (4.48) |

| Psychological Aggression | 1.86 (0.89) | 1.86 (0.88) | 2.15 (1.17) | 2.00 (1.03) | 1.95 (0.96) | 1.94 (1.04) | 2.03 (1.11) |

| Physical Aggression | 1.14 (0.33) | 1.14 (0.38) | 1.25 (0.53) | 1.18 (0.37) | 1.14 (0.33) | 1.12 (0.32) | 1.12 (0.36) |

Table 2 reports the results of the primary analyses.

Table 2.

Summary of Multilevel Models Testing the Between and Within Person Effects of Relational Risk Factors and Dating Aggression

| Psychological Aggression Involvement | Physical Aggression Involvement | |

|---|---|---|

| Negative Interactions | ||

| Intercept (β0) | 1.98 (.22) | 1.17 (.10) |

| Mean Negative Interactions(γ01) | 1.35*** (.12) .41 | 0.26*** (.05) .13 |

| Age (β1) | 0.02 (.01) .00 | −0.01 (.00) .00 |

| Negative Interactions (β2) | 0.70*** (.04) .26 | 0.16*** (.02) .07 |

| Gender Main Effect (γ02) | 0.02 (.08) .00 | −0.03 (.03) .00 |

| Mean Negative Interactions X Negative Interactions (γ22) | 0.11 (.12) .00 | 0.13* (.05) .01 |

| Age X Gender (γ11) | −0.01 (.02) .00 | 0.00 (.01) .00 |

| Mean Negative Interactions X Gender (γ03) | 0.18 (.24) .00 | 0.16 (.10) .01 |

| Negative Interactions X Gender (γ21) | 0.08 (.08) .00 | 0.03 (.04) .00 |

| Jealousy Intercept (β0) | 1.84 (.25) | 1.13 (.10) |

| Mean Jealousy (γ01) | 1.49*** (.23) .19 | 0.21* (.08) .04 |

| Age (β1) | 0.01 (.01) .00 | −0.01 (.00) .00 |

| Jealousy (β2) | 0.60*** (.08) .06 | 0.10** (.03) .02 |

| Gender Main Effect (γ02) | −0.12 (.09) .01 | −0.06 (.03) .01 |

| Mean Jealousy X Jealousy (γ22) | 0.33 (.41) .00 | 0.22* (.11) .01 |

| Age X Gender (γ11) | −0.00 (.02) .00 | 0.00 (.01) .00 |

| Mean Jealousy X Gender (γ03) | 0.12 (.45) .00 | −0.26 (.17) .00 |

| Jealousy X Gender (γ21) | −0.22 (.16) .00 | −0.13* (.06) .01 |

| Support | ||

| Intercept (β0) | 1.80 (.27) | 1.13 (.10) |

| Mean Support (γ01) | −0.15 (.11) .01 | −0.07 (.04) .01 |

| Age (β1) | 0.02 (.01) .00 | −0.01 (.01) .00 |

| Support (β2) | −0.05 (.04) .00 | −0.02 (.02) .00 |

| Gender Main Effect (γ02) | −0.07 (.10) .00 | −0.04 (.04) .01 |

| Mean Support X Support (γ22) | −0.23* (.12) .01 | −0.02 (.05) .00 |

| Age X Gender (γ11) | −0.00 (.02) .00 | 0.01 (.01) .00 |

| Mean Support X Gender (γ03) | 0.13 (.21) .00 | 0.04 (.07) .00 |

| Support X Gender (γ21) | −0.05 (.08) .00 | −0.05 (.03) .00 |

| Relationship Satisfaction | ||

| Intercept (β0) | 1.84 (.07) | 1.15 (.03) |

| Mean Relationship Satisfaction (γ01) | −0.12** (.03) .08 | −0.02* (.01) .02 |

| Age (β1) | 0.02 (.01) .00 | −0.00 (.00) .00 |

| Relationship Satisfaction (β2) | −0.06*** (.01) .04 | −0.01*** (.00) .02 |

| Gender Main Effect (γ02) | −0.04 (.10) .00 | −0.03 (.04) .00 |

| Mean Relationship Satisfaction X Relationship Satisfaction (γ22) | −0.00 (.00) .00 | 0.002* (.00) .01 |

| Age X Gender (γ11) | −0.04 (.07) .00 | −0.01 (.03) .00 |

| Mean Relationship Satisfaction X Gender (γ03) | −0.02 (.07) .00 | −0.05 (.03) .01 |

| Relationship Satisfaction X Gender (γ21) | −0.03 (.02) .00 | −0.02* (.01) .01 |

Notes. The primary numbers in the table are the unstandardized coefficients for the fixed effects.

Standard errors are in parentheses. Effect sizes follow the standard errors for the involvement measure of dating aggression.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

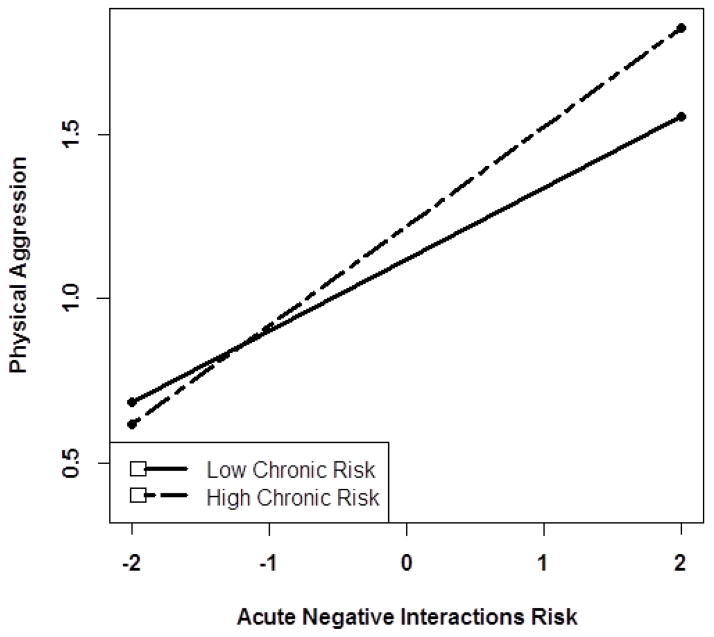

Negative Interactions

In terms of between-person (chronic) and within person (acute) effects, greater levels of negative interactions were associated with greater psychological and physical aggression. For physical aggression, significant interactions between the chronic and acute effects emerged. To further interpret the interactions, we used Preacher, Curran, & Bauer’s (2006) computational tools to plot the estimated effects of within-person (acute) relational risk factors for physical aggression for two values of between-person relational risk factors: 1 SD above the mean for the between-person effect of the relational risk factor (i.e., “high chronic risk”) and 1 SD below the mean (i.e., “low chronic risk”). For both those with high and low chronic risk, acute increases in negative interactions were associated with physical aggression (β = 0.30, p < .001; β = 0.22, p < .001, respectively), though the effect was stronger for those with high chronic risk (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Interaction between within-person negative interactions and between-person negative interactions on physical aggression. The two lines depict the association between within-person levels of negative interactions and physical aggression at one SD below the mean of between-person level of negative interactions (labeled “low chronic risk”), and one SD above the mean of between-person level of negative interactions (labeled “high chronic risk”).

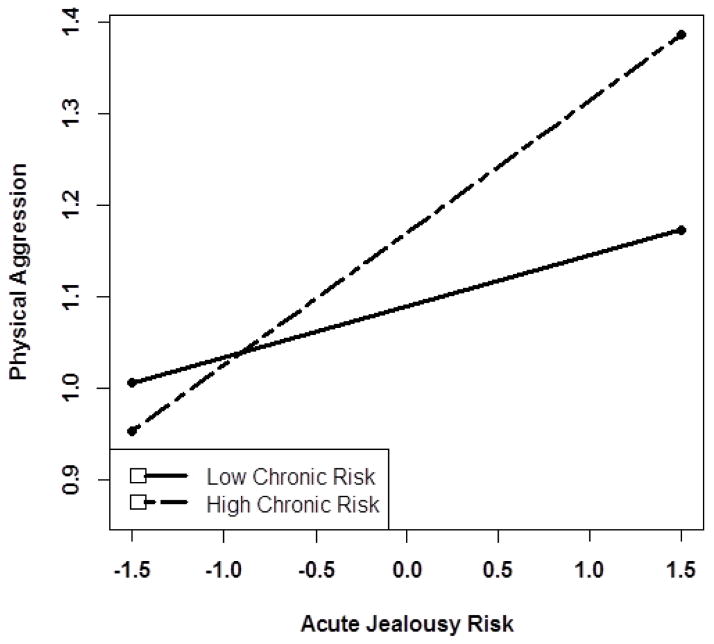

Jealousy

In terms of between-person (chronic) and within-person (acute) effects, greater levels of jealousy were associated with greater psychological and physical aggression. For physical aggression, significant interactions between the chronic and acute effects emerged such that acute increases in jealousy was associated with physical aggression for those with high chronic risk (β = 0.14, p < .001), but not for those with low chronic risk (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Interaction between within-person jealousy and between-person jealousy on physical aggression. The two lines depict the association between within-person levels of jealousy and physical aggression at one SD below the mean of between-person level of jealousy (labeled “low chronic risk”), and one SD above the mean of between-person level of jealousy (labeled “high chronic risk”).

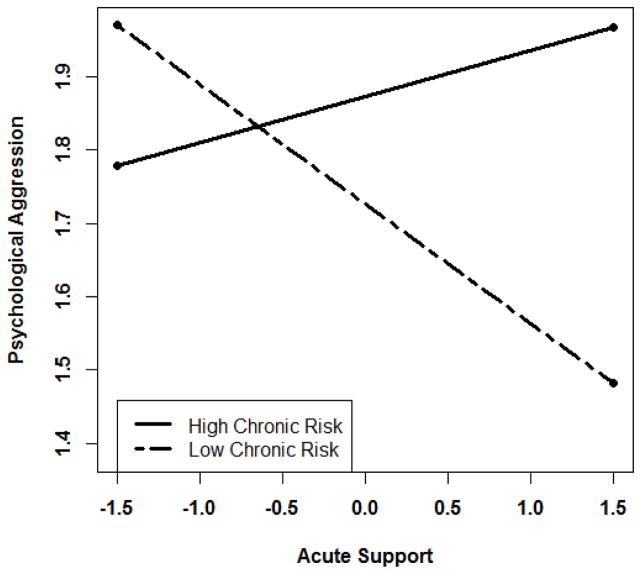

Support

For psychological aggression, there was a significant interaction of the between-person (chronic) and within-person (acute) effects; acute increases in support were negatively associated with psychological aggression (β = −0.16, p = .02), but only for those with low chronic risk (i.e., high support on average) (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Interaction between within-person support and between-person support on psychological aggression. The two lines depict the association between within-person levels of support and psychological aggression at one SD below the mean of between-person level of support (labeled “high chronic risk”), and one SD above the mean of between-person level of support (labeled “low chronic risk”).

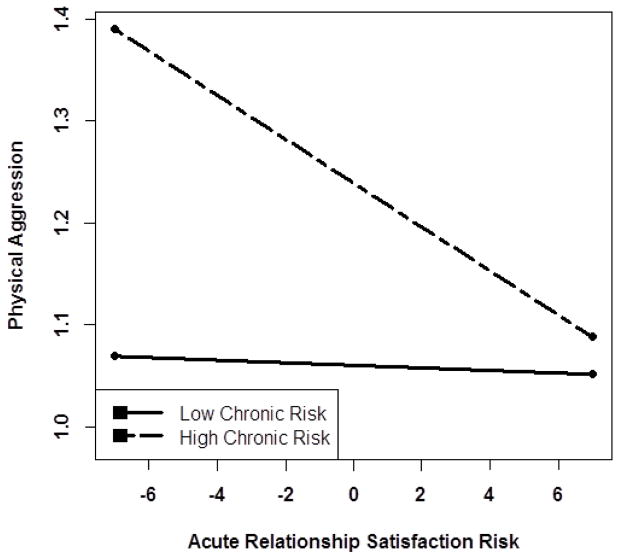

Relationship Satisfaction

In terms of between-person (chronic) and within-person (acute) effects, lower levels of relationship satisfaction were associated with greater psychological and physical aggression. For physical aggression, significant interactions of the between-person and within-person effects emerged such that acute increases in relationship satisfaction were negatively associated with physical aggression for those with high chronic risk (i.e., low relationship satisfaction on average) (β = minus;0.02, p < .001), but not for those with low chronic risk (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Interaction between within-person relationship satisfaction and between-person relationship satisfaction on physical aggression. The two lines depict the association between within-person levels of relationship satisfaction and physical aggression at one SD below the mean of between-person level of relationship satisfaction (labeled “high chronic risk”), and one SD above the mean of between-person level of relationship satisfaction (labeled “low chronic risk”).

Gender

No main effects of gender were found. No interaction effects were found between age and gender. We then tested interactions between each chronic and acute relational risk factor and gender for physical dating aggression involvement. Out of 16 potential interactions, only 2 instances of a significant interaction with gender emerged. Specifically, acute increases in jealousy were associated with increases in physical dating aggression involvement for women (β = .13, p = .01), but not men. Similarly, acute reductions in relationship satisfaction were associated with increases in physical dating aggression involvement for women (β = minus;0.02, p < .001), but not men.

Age

No main effects of age were found.

Severe and Mild Psychological Aggression

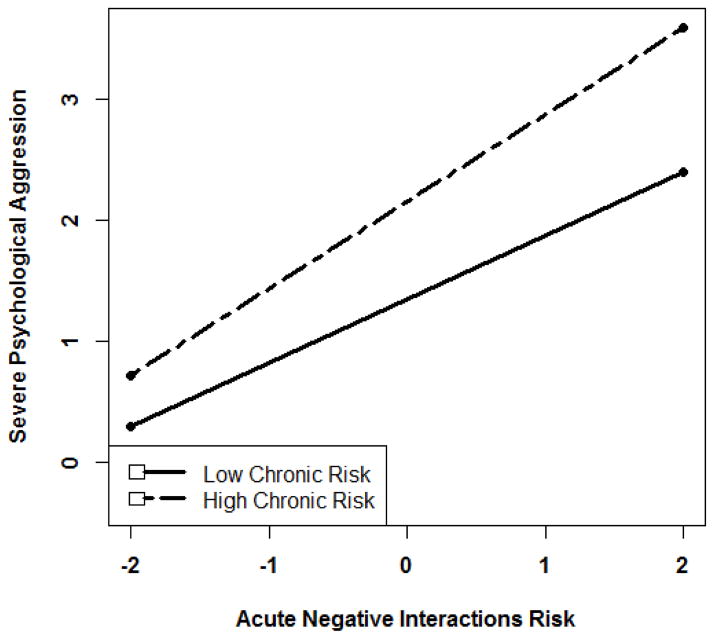

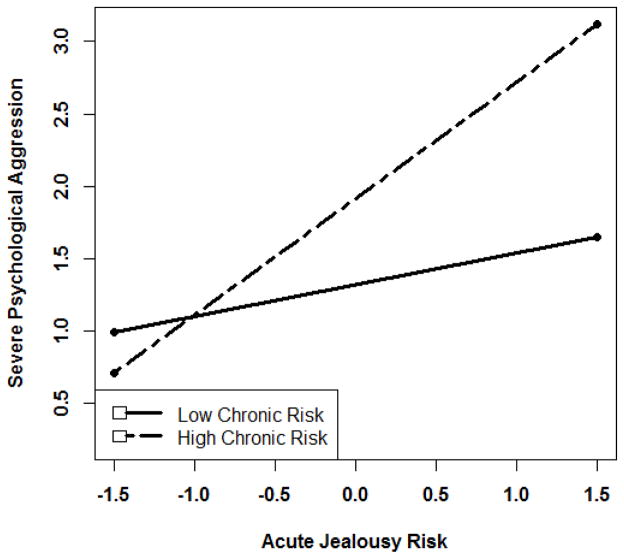

In the prior analyses, interaction effects between chronic and acute risk emerged for physical aggression, but they did not for psychological aggression. One reason such effects may not have emerged is because of the commonality of psychological aggression; thus, we suspected that distinguishing between mild and severe degrees of psychological aggression may yield different patterns. In a series of post-hoc exploratory analyses, we examined associations between chronic and acute effects and mild or severe psychological aggression separately. For mild psychological aggression, the patterns mirrored those of the broader psychological aggression measure. That is, main effects of both chronic and acute risk in the form of negative interactions, jealousy, and relationship satisfaction were related to mild psychological aggression (see Table 3); no interactions between chronic and acute risk were found. In contrast, the main effects of chronic and acute risk for severe psychological aggression were qualified by significant interactions between chronic and acute risk also emerged. For both those with high and low chronic risk, acute increases in negative interactions were associated with physical aggression (β = 0.52, p < .001; β = 0.72, p < .001, respectively), though the effect was stronger for those with high chronic risk (see Figure 5). Similarly, significant interactions between the chronic and acute effects emerged such that acute increases in jealousy were associated with physical aggression for those with high chronic risk (β = 0.80, p < .001), but not for those with low chronic risk (see Figure 6).

Table 3.

Summary of Multilevel Models Testing the Between and Within Person Effects of Relational Risk Factors and Dating Aggression Victimization and Perpetration

| Psychological Aggression Victimization | Psychological Aggression Perpetration | Physical Aggression Victimization | Physical Aggression Perpetration | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative Interactions | ||||

| Intercept (β0) | 1.82 (.26) | 2.15 (.24) | 1.19 (.12) | 1.15 (.10) |

| Mean Negative Interactions(γ01) | 1.41*** (.13) .40 | 1.27*** (.12) .38 | 0.30*** (.06) .12 | 0.23*** (.05) .10 |

| Age (β1) | 0.02 (.01) .01 | 0.01 (.01) .00 | −0.01 (.01) .00 | −0.00 (.00) .00 |

| Negative Interactions (β2) | 0.75*** (.05) .21 | 0.65*** (.05) .16 | 0.18*** (.02) .09 | 0.14*** (.02) .05 |

| Gender Main Effect (γ02) | −0.01 (.09) .00 | 0.05 (.08) .02 | −0.08 (.04) .02 | 0.01 (.03) .00 |

| Mean Negative Interactions X Negative Interactions (γ22) | 0.00 (.14) .00 | 0.22 (.13) .00 | 0.11 (.06) .00 | 0.15* (.06) .01 |

| Age X Gender (γ11) | −0.01 (.02) .00 | −0.01 (.02) .00 | 0.00 (.01) .00 | 0.00 (.01) .00 |

| Mean Negative Interactions X Gender (γ03) | 0.18 (.27) .00 | 0.18 (.25) .00 | 0.11 (.12) .01 | 0.23* (.10) .03 |

| Negative Interactions X Gender (γ21) | 0.06 (.10) .00 | 0.10 (.09) .00 | 0.02 (.05) .00 | 0.04 (.04) .00 |

| Jealousy | ||||

| Intercept (β0) | 1.67 (.29) | 2.03 (.26) | 1.15 (.12) | 1.11 (.10) |

| Mean Jealousy (γ01) | 1.59*** (.25) .18 | 1.40*** (.23) .17 | 0.26* (.10) .04 | 0.17* (.08) .03 |

| Age (β1) | 0.02 (.01) .01 | 0.01 (.01) .00 | −0.01 (.01) .00 | −0.00 (.00) .00 |

| Jealousy (β2) | 0.61*** (.09) .05 | 0.60*** (.08) .06 | 0.12** (.04) .01 | 0.07* (.03) .01 |

| Gender Main Effect (γ02) | −0.16 (.10) .01 | −0.09 (.09) .01 | −0.10* (.04) .03 | −0.03 (.03) .01 |

| Mean Jealousy X Jealousy (γ22) | 0.24 (.55) .00 | 0.42 (.50) .00 | 0.64* (.25) .01 | 0.37* (.18) .01 |

| Age X Gender (γ11) | −0.01 (.03) .00 | 0.01 (.01) .00 | 0.01 (.01) .00 | 0.00 (.01) .00 |

| Mean Jealousy X Gender (γ03) | −0.06 (.50) .00 | 0.23 (.46) .00 | −0.39 (.20) .02 | −0.12 (.17) .00 |

| Jealousy X Gender (γ21) | −0.17 (.19) .00 | −0.27 (.17) .00 | −0.11 (.08) .00 | −0.15* (.07) .01 |

| Support | ||||

| Intercept (β0) | 1.63 (.30) .01 | 1.98 (.28) | 1.15 (.12) | 1.12 (.11) |

| Mean Support (γ01) | −0.17 (.12) .01 | −0.12 (.11) .01 | −0.06 (.04) .01 | 0.01 (.03) .00 |

| Age (β1) | 0.02 (.01) .00 | 0.02 (.01) .01 | −0.01 (.01) .00 | −0.00 (.01) .00 |

| Support (β2) | −0.08 (.05) .01 | −0.02 (.04) .00 | −0.02 (.02).00 | −0.02 (.02) .01 |

| Gender Main Effect (γ02) | −0.11 (.11) .00 | −0.05 (.10) .00 | −0.09* (.04) .03 | 0.01 (.03) .00 |

| Mean Support X Support (γ22) | −0.26* (.13) .00 | −0.18 (.12) .00 | −0.00 (.06) .00 | −0.24* (.05) .03 |

| Age X Gender (γ11) | −0.01 (.03) .00 | 0.01 (.02) .00 | 0.01 (.01) .00 | 0.01 (.01) .00 |

| Mean Support X Gender (γ03) | 0.14 (.23) .00 | 0.11 (.21) .00 | 0.01 (.09) .00 | 0.08 (.07) .01 |

| Support X Gender (γ21) | −0.10 (.09) .00 | 0.02 (.08) .00 | −0.07 (.04) .00 | −0.03 (.03) .00 |

| Relationship Satisfaction | ||||

| Intercept (β0) | 1.83 (.08) | 1.85 (.07) | 1.13 (.03) | 1.14 (.03) |

| Mean Relationship Satisfaction (γ01) | −0.12*** (.03) .08 | −0.12*** (.03) .08 | −0.02 (.01) .02 | −0.03** (.01) .05 |

| Age (β1) | 0.02 (.01) .01 | 0.01 (.01) .00 | −0.01 (.01) .00 | 0.00 (.01) .00 |

| Relationship Satisfaction (β2) | −0.08*** (.01) .07 | −0.06*** (.01) .04 | −0.01*** (.001) .10 | −0.01** (.003) .01 |

| Gender Main Effect (γ02) | −0.09 (.11) .00 | −0.01 (.10) .00 | −0.08* (.04) .02 | 0.01 (.03) .00 |

| Mean Relationship Satisfaction X Relationship Satisfaction (γ22) | 0.00 (.00) .00 | 0.00 (.00) .00 | 0.002* (.001) .01 | 0.002** (.001) .01 |

| Age X Gender (γ11) | −0.02 (.08) .00 | −0.04 (.07) .00 | −0.02 (.08) .00 | 0.01 (.03) .00 |

| Mean Relationship Satisfaction X Gender (γ03) | −0.07 (.07) .01 | 0.02 (.07) .00 | −0.07 (.07) .01 | −0.04 (.02) .02 |

| Relationship Satisfaction X Gender (γ21) | −0.03 (.02) .00 | −0.03 (.02) .00 | −0.04* (.02) .01 | −0.02* (.01) .01 |

Notes. The primary numbers in the table are the unstandardized coefficients for the fixed effects.

Standard errors are in parentheses. Effect sizes follow the standard errors for the involvement measure of dating aggression.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

Figure 5.

Interaction between within-person negative interactions and between-person negative interactions on severe psychological aggression. The two lines depict the association between within-person levels of negative interactions and psychological aggression at one SD below the mean of between-person level of negative interactions (labeled “high chronic risk”), and one SD above the mean of between-person level of negative interactions (labeled “low chronic risk”).

Figure 6.

Interaction between within-person jealousy and between-person jealousy on severe psychological aggression. The two lines depict the association between within-person levels of jealousy and severe psychological aggression at one SD below the mean of between-person level of severe psychological aggression (labeled “high chronic risk”), and one SD above the mean of between-person level of jealousy (labeled “low chronic risk”).

Perpetration and Victimization

In other secondary analyses, we examined how the risk factors were associated with perpetration and victimization, separately. We conducted the same models as those reported on previously, but examined effects with psychological dating aggression perpetration and victimization separately as well as physical dating aggression perpetration and victimization separately. We found similar broad patterns of effects as those found using an involvement model (see Tables 2 & 3).

Discussion

This study used a relational risk factor framework to better understand both acute and chronic risk for dating aggression. Relational risk factors are understudied, yet emerging empirical work suggests that they may be critical to our understanding of dating aggression and its development. The current findings bolster the relational risk framework’s proposition that relational risk factors warrant a larger role in conceptual and empirical models of dating aggression. Additionally, this study contributed by examining when, and for whom, relational risk factors are associated with dating aggression.

Notably, we found similar broad patterns of effects when examining effects using an involvement model (i.e., victimization and perpetration together) and when examining each separately. Such a pattern is consistent with the idea that perpetration and victimization so frequently co-occur that it is difficult, and perhaps conceptually unwarranted, to disentangle the two (Connolly et al., 2010). Thus, we discuss the results in the context of an involvement model only.

Relational Context and Dating Aggression

Consistent with Reese-Weber and Johnson’s (2013) relational risk framework, between- and within-person effects on both psychological and physical aggression were found for negative interactions, jealousy, and relationship satisfaction. The presence of between-person effects indicates that individuals with chronically more negative interactions and greater jealousy as well as lower relationship satisfaction are at greater risk for dating aggression. Such a pattern is consistent with prior cross-sectional work (Cano, Avery-Leaf, Cascardi, & O’Leary, 1998; Marcus & Swett, 2002; O’Keefe, 1997; O’Keefe & Treister, 1998) as well as person-oriented results (Burk & Seiffge-Krenke, 2015). The present study extends these findings by showing the pattern of effects in youth ranging in age from middle adolescence to early adulthood.

In addition, acute increases in negative interactions and jealousy as well as worse relationship satisfaction; that is, more risk than is typical for that person was associated with greater likelihood of dating aggression. The presence of acute risk is consistent with ecological models of dating aggression (e.g., Capaldi, Kim, & Shortt, 2004), and suggests that, among adolescents and young adults, risk may be partially dyad dependent. That is, increases and decreases in risk within a specific relationship, or across dyads, are associated with changes in experiencing aggression. Moreover, risk could be either stable or variable depending on whether the relationship(s) varies or is relatively consistent. These finding are important as they suggest that intervention efforts to decrease acute relationship risk may be a promising means of reducing dating aggression. Taken together, these findings provide further evidence that relational risk factors are indeed an important aspect of theories aiming to understand dating aggression. Additionally, they highlight the need for a greater focus on relational risk factors in the dialogue to reduce dating aggression among adolescents and young adults.

The current findings are also notable in their consistency. Between-person and within-person effects are often not the same (Curran & Bauer, 2001). The presence of consistent between and within person effects allows us to reduce the number of likely alternative explanations of the current findings. Specifically, for a third variable to explain these effects it would need to be sufficiently stable to allow for the between-person effects, but not so stable to preclude the within-person effects. Moreover, it would need to covary with both the relational risk factors and dating aggression. These are challenging criteria for a third variable to meet.

Interactions between Chronic and Acute Risk

The current study also examined the interactions between chronic risk and acute risk of relational factors, something we believe has not been done previously. Significant interactions were found for negative interactions, jealousy, and relationship satisfaction in predicting physical aggression.

These interactions revealed a pattern in which those with high chronic risk may be more affected by changes in their acute risk. Specifically, the increase in acute risk for those with high chronic risk was associated with a significant increase in physical aggression, whereas increases in acute risk for those with low chronic risk were not associated with increases in physical aggression. Moreover, when acute risk was low for those with high chronic risk, they had similar levels of physical aggression as those with low chronic risk. That is, decreases in acute risk may be able to return those who are usually at high risk to low levels of risk. Thus, although they may be susceptible to increases in relational risk, they are also more likely to benefit from reductions in acute risk. Consequently, these results indicate that we should not treat risk as static; rather, risk is dynamic and influenced by both acute and chronic factors simultaneously. As such, we should aim to conduct our assessments in a manner that captures risk’s dynamic nature, by conducting multiple levels of analysis and gathering longitudinal data.

The presence of interactions between chronic and acute risk also suggest that intervention efforts targeting relational risk factors among adolescents and young adults may be particularly fruitful. Even incremental change in acute risk, as noted in the presence of within-person effects, particularly for those considered at high risk, may be protective. Further, the opportunity to address relational context risk factors may be greater before youth enter into marital relationships and relational processes become more stabilized. Further work should aim to parse apart potential mechanisms of these interactions by assessing changes in relational risk within specific dyads and examining multiple levels of risk (e.g., individual risk factors, developmental characteristics) in conjunction with the relational context.

Notably, unlike the main effects, the patterns of interactions were not the same across both psychological and physical aggression; rather, the interactions between chronic and acute risk were only found for predicting physical aggression in most instances. The only significant interaction for psychological aggression was support. We hypothesized that the broad lack of interaction effects for psychological aggression may be related to the commonality of psychological aggression. If this was the case, then acute changes in risk may more easily translate to greater psychological aggression, regardless of the level of chronic risk. To test this hypothesis, we conducted a series of exploratory analyses in which we distinguished between mild and severe psychological aggression. As expected, the main effects for both mild and severe psychological aggression were the same and were consistent with the broader measure of psychological aggression. However, interactions between chronic and acute risk emerged for severe psychological aggression, but not mild psychological aggression. Further, these interactions are similar in pattern to those for physical aggression. Taken together, this pattern suggests that more intense psychological aggression may have similar effects as physical aggression. Although exploratory, these results suggest that researchers should consider examining the severity of the psychological aggression to avoid potentially overstating effects which may only be true for more severe psychological aggression or to avoid failing to capture significant effects.

Gender

No main effects of gender were found for dating aggression. This is consistent with other work in both adolescence (Brooks-Russell, Foshee, & Reyes, 2015) and young adulthood (Capaldi, et al., 2012) that has shown similar rates of dating aggression across genders. We also examined interactions between gender and each chronic relational risk factor and each acute relational risk factor. Out of 16 potential interactions, only 2 instances of significant effects emerged for dating aggression involvement. Acute increases in jealousy and decreases in relationship satisfaction were associated with increased risk for dating aggression in involvement for women but not men. This pattern is consistent with some work suggesting that relational risk factors may be especially important for understanding the etiology of women’s dating aggression (Luthra & Gidycz, 2006). However, future work with a larger sample size should aim to replicate these patterns, as the small proportion of significant effects suggests they may be spurious.

Limitations

There are several notable limitations in the current study. First, it is limited by its reliance on self-report assessments of both relational risk factors and dating aggression. Future research should strive to examine relational risk factors through observations of dyads to further understand these processes. Additionally, although the current study assessed both aggression perpetration and victimization, reports were made only by one member of the dyad.

The current study is strengthened by its longitudinal design spanning adolescence into young adulthood, but as a consequence, we were limited to collecting data on a moderate size sample of 200 participants. Future work with a larger sample would benefit from examining additional factors and moderators of the effects. For example, the predominance of bidirectional aggression in the current study precluded conducting analyses examining unidirectional vs. bidirectional perpetration and victimization. Further work assessing aggression from both partners’ perspective and including sufficient power to examine unidirectional aggression is necessary. Additionally, although the sample was representative of the ethnic and racial composition of the United States, we did not have a sufficient number of each ethnic and racial minority to examine potential differences in the role of relational risk factors. Evidence suggests heterogeneity exists across different racial and ethnic groups with regard to dating aggression, and so future work should examine potential racial/ethnic differences in the pattern of results observed in this study (O’Leary, Slep, Avery-Leaf, & Cascardi, 2008). Finally, we did not have sufficient power to examine potential interactions between the status of a relationship (e.g., cohabitation) and relational risk factors in association with dating aggression. Future work should test for such potential effects, as we may anticipate that relational risk factors become increasingly important as relationship commitment increases.

Although we examined both between- and within-person effects, the associations were concurrent; therefore we were unable to determine the directionality of the links between relational factors and dating aggression. For the purposes of the present article, we focused solely on the relational variables as risk factors, due to the relational theoretical framework. However, it is also possible that greater levels of aggression negatively impact relational characteristics. Indeed, such effects would be equally interesting. This pattern would indicate that both chronic and acute experiences of dating aggression negatively impact relational characteristics. Such adverse relationship experiences may be partially responsible for the physical and psychological consequences frequently linked to interpersonal violence (see Lawrence, Orengo-Aguayo, Langer, & Brock, 2012). Perhaps most likely, and consistent with a relational theoretical framework, a feedback loop may exist wherein relational risk factors contribute to aggression in a relationship which then increase relational risk factors. Longitudinal studies that examine such changes would help elucidate these potential processes. Additionally, relational risk factors are theorized to contribute to greater risk for dating aggression by increasing the frequency and severity of conflict which may then escalate. The current study, however, did not examine the nature of conflict that occurred most proximally to the incidences of dating aggression. Future work aimed at understanding the potential mechanisms through which relational risk factors contribute to risk should address this facet of a relational risk framework.

Conclusion

Past cross-sectional research has examined the links between relational risk factors and dating aggression (Capaldi et al., 2012). To the best of our knowledge, however, the current study is the first to demonstrate the critical role of relational risk factors by examining both between (chronic) and within (acute) person effects longitudinally. Consistent with Reese-Weber and Johnson’s (2013) relational risk framework, we found between- and within-person effects on both psychological and physical aggression for negative interactions, jealousy, and relationship satisfaction. The presence of between-person effects indicates that individuals with chronically more negative interactions and greater jealousy as well as lower relationship satisfaction are at greater risk for dating aggression, which is consistent with prior cross-sectional work. Moreover, when someone was engaged in more negative interactions, more jealous, or less satisfied with the relationship than usual, she or he was at greater risk for dating aggression. The presence of acute risk suggests that risk may be partially relationship specific. Moreover, the present study examined and found significant interactions between chronic and acute risk in predicting physical aggression. Those with higher levels of chronic risk are more vulnerable to changes in acute risk. Accordingly, relational risk factors may be particularly important targets for interventions as the pattern of results suggests that relational risk factors are dynamic, not static; thus, they may be responsive to intervention efforts to change them. Taken together, the findings contribute to a greater understanding of relational risk factors for aggression and underscore their importance for researchers, policy developers, and care providers working toward the reduction of dating aggression in adolescence and young adulthood.

Table 4.

Summary of Multilevel Models Testing the Between and Within Person Effects of Relational Risk Factors and Degree of Psychological Aggression

| Mild Psychological Aggression Involvement | Mild Psychological Aggression Victimization | Mild Psychological Aggression Perpetration | Severe Psychological Aggression Involvement | Severe Psychological Aggression Victimization | Severe Psychological Aggression Perpetration | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative Interactions | ||||||

| Intercept (β0) | 2.25 (.27) | 1.91 (.30) | 2.60 (.30) | 1.75 (.25) | 1.76 (.30) | 1.74 (.27) |

| Mean Negative Interactions(γ01) | 1.56*** (.13) | 1.64*** (.07) | 1.47*** (.14) | 1.26*** (.14) | 1.34 (.15) | 1.18*** (.14) |

| Age (β1) | 0.02* (.01) | 0.02 (.01) | 0.03* (.01) | .02 (.01) | 0.03* (.01) | 0.01 (.01) |

| Negative Interactions (β2) | 0.74*** (.06) | 0.81*** (.07) | 0.68*** (.06) | .62*** (.05) | 0.69*** (.06) | 0.56*** (.06) |

| Gender Main Effect (γ02) | 0.01 (.09) | −0.01 (.10) | 0.03 (.09) | .07 (.09) | 0.04 (.10) | 0.09 (.09) |

| Mean Negative Interactions X Negative Interactions (γ21) | 0.12 (.15) | 0.10 (.17) | 0.16 (.17) | .30* (.14) | 0.17 (.16) | 0.41** (.15) |

| Jealousy | ||||||

| Intercept (β0) | 2.10 (.30) | 1.75 (.34) | 2.47 (.32) | 1.63 (.28) | 1.62 (.32) | 1.63 (.30) |

| Mean Jealousy (γ01) | 1.82*** (.25) | 1.85*** (.28) | 1.80*** (.25) | 1.41*** (.25) | 1.56*** (.27) | 1.29*** (.25) |

| Age (β1) | 0.02 (.01) | 0.02 (.02) | 0.02 (.02) | 0.01 (.01) | 0.03 (.02) | 0.00 (.01) |

| Jealousy (β2) | 0.69*** (.10) | 0.70*** (.12) | 0.66*** (.11) | 0.51*** (.09) | 0.47*** (.11) | 0.55*** (.10) |

| Gender Main Effect (γ02) | −0.15 (.10) | −0.18 (.12) | −0.13 (.11) | −0.05 (.10) | −0.08 (.11) | −0.02 (.10) |

| Mean Jealousy X Jealousy (γ21) | 0.45 (.45) | 0.23 (.51) | 0.68 (.49) | 1.39** (.42) | 1.52** (.49) | 1.25** (.44) |

| Support | ||||||

| Intercept (β0) | 2.03 (.31) | 1.68 (.35) | 2.40 (.33) | 1.61 (.30) | 1.60 (.33) | 1.62 (.31) |

| Mean Support (γ01) | −0.15 (.12) | −0.16 (.13) | −0.12 (.12) | −0.16 (.11) | −0.19 (.12) | −0.13 (.12) |

| Age (β1) | 0.02 (.01) | 0.02 (.02) | 0.02 (.01) | 0.02 (.01) | 0.03 (.01) | 0.01 (.01) |

| Support (β2) | −0.06 (.05) | −0.10 (.05) | −0.02 (.05) | −0.05 (.04) | −0.08 (.05) | −0.02 (.05) |

| Gender Main Effect (γ02) | −0.10 (.12) | −0.13 (.13) | −0.08 (.12) | −0.02 (.11) | −0.05 (.12) | 0.00 (.11) |

| Mean Support X Support (γ21) | −0.24 (.13) | −0.31* (.14) | −0.18 (.14) | −0.11 (.12) | −0.16 (.14) | −0.08 (.12) |

| Relationship Satisfaction Intercept (β0) | 2.03 (.08) | 1.96 (.09) | 2.09 (.09 | 1.67 (.08) | 1.71 (.09) | 1.63 (.08) |

| Mean Relationship Satisfaction (γ01) | −0.13** (.04) | −0.14** (.04) | −0.12** (.04) | −0.11** (.03) | 0.13** (.04) | 0.11** (.04) |

| Age (β1) | 0.02 (.01) | 0.02 (.02) | 0.02 (.01) | 0.02 (.01) | 0.03* (.01) | 0.01 (.01) |

| Relationship Satisfaction (β2) | −0.08*** (.01) | −0.10*** (.01) | −0.07*** (.01) | −0.07*** (.01) | −0.09*** (.01) | −0.06*** (.01) |

| Gender Main Effect (γ02) | −0.06 (.11) | −0.09 (.12) | −0.04 (.11) | 0.02 (.11) | −0.02 (.12) | 0.04 (.11) |

| Mean Relationship Satisfaction X Relationship Satisfaction (γ21) | −0.00 (.00) | −0.00 (.00) | −0.00 (.00) | 0.00 (.00) | −0.00 (.00) | 0.00 (.00) |

Notes. The primary numbers in the table are the unstandardized coefficients for the fixed effects. Standard errors are in parentheses.

p< .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this manuscript was supported by Grant 050106 from the National Institute of Mental Health (WF, P.I.), Grant 049080 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (WF, P.I.), and the preparations of this manuscript was supported by F31 AA023692 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (CC, P.I.). Appreciation is expressed to the Project Star staff for their assistance in collecting the data, and to the Project Star participants and their partners, friends and families.

Funding: This study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (grant number 050106), the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (grant number 049080). Preparation of this manuscript was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (grant number 023692).

Biographies

Charlene Collibee is a PhD candidate in the Clinical Psychology program at the University of Denver. Her primary research interests are romantic relationships and interpersonal risk and resilience across development

Dr. Wyndol Furman is a John Evans Professor and Director of Clinical Training at the University of Denver. He studies close relationships in adolescence and early adulthood.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report no conflict of interests.

Authors Contributions

CC and WF conceived of the study together. CC performed the statistical analyses, interpretation of the data, and drafted the manuscript. WF also participated in the interpretation of the data and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- Behrens JT. Principles and procedures of exploratory data analysis. Psychological Methods. 1997;2:131–160. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.2.2.131. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Breiding MJ, Chen J, Black MC. Intimate Partner Violence in the United States — 2010. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Russell A, Foshee VA, Reyes HLM. Dating Violence. In: Gullotta TP, Plant RW, Evans M, editors. Handbook of adolescent behavioral problems. New York, NY: Springer US; 2015. pp. 559–576. [Google Scholar]

- Burk WJ, Seiffge-Krenke I. One-sided and mutually aggressive couples: Differences in attachment, conflict prevalence, and coping. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.08.011. Advanced online publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano A, Avery-Leaf S, Cascardi M, O'Leary KD. Dating violence in two high school samples: Discriminating variables. Journal of Primary Prevention. 1998;18:431–446. doi: 10.1023/A:1022653609263. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Kim HK, Shortt JW. Women’s involvement in aggression in young adult romantic relationships: A developmental systems model. In: Putallez M, Bierman KL, editors. Aggression, antisocial behavior, and violence among girls: A developmental perspective. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2004. pp. 223–241. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Knoble NB, Shortt JW, Kim HK. A systematic review of risk factors for intimate partner violence. Partner Abuse. 2012;3:231–280. doi: 10.1891/1946-6560.3.2.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly J, Friedlander L, Pepler D, Craig W, Laporte L. The ecology of adolescent dating aggression: Attitudes, relationships, media use, and socio-demographic risk factors. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2010;19:469–491. [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. The disaggregation of within-person and between-person effects in longitudinal models of change. Annual Review of Psychology. 2011;62:583–619. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foran HM, O'Leary KD. Alcohol and intimate partner violence: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:1222–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Buhrmester D. Methods and measures: The network of relationships inventory: Behavioral systems version. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2009;33:470–478. doi: 10.1177/0165025409342634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Low S, Ho MJ. Romantic experience and psychosocial adjustment in middle adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2009;38:75–90. doi: 10.1080/15374410802575347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano PC, Soto DA, Manning WD, Longmore MA. The characteristics of romantic relationships associated with teen dating violence. Social Science Research. 2010;39:863–874. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray HM, Foshee V. Adolescent dating violence differences between one-sided and mutually violent profiles. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1997;12:126–141. doi: 10.1177/088626097012001008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaura SA, Lohman BJ. Dating violence victimization, relationship satisfaction, mental health problems, and acceptability of violence: A comparison of men and women. Journal of Family Violence. 2007;22:367–381. doi: 10.1007/s10896-007-9092-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kurdek LA. Conflict resolution styles in gay, lesbian, heterosexual nonparent, and heterosexual parent couples. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1994:705–722. [Google Scholar]

- Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, Selwyn C, Rohling ML. Rates of bidirectional versus unidirectional intimate partner violence across samples, sexual orientations, and race/ethnicities: A comprehensive review. Partner Abuse. 2012;3:199–230. doi: 10.1891/1946-6560.3.2.199. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence E, Orengo-Aguayo R, Langer A, Brock RL. The impact and consequences of partner abuse on partners. Partner Abuse. 2012;3:406–428. doi: 10.1891/1946-6560.3.4.406. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luthra R, Gidycz CA. Dating violence among college men and women: Evaluation of a theoretical model. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2006;21:717–731. doi: 10.1177/0886260506287312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus RF, Swett B. Violence and intimacy in close relationships. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2002;17:570–586. doi: 10.1177/0886260502017005006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy CM, O'Leary KD. Psychological aggression predicts physical aggression in early marriage. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1989;57:79–89. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.57.5.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray CE, Kardatzke KN. Dating violence among college students: Key issues for college counselors. Journal of College Counseling. 2007;10:79–89. doi: 10.1002/j.2161-1882.2007.tb00008.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Norton R. Measuring marital quality: A critical look at the dependent variable. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1983;45:141–151. [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe M. Predictors of dating violence among high school students. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1997;12:546–568. doi: 10.1177/088626097012004005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O'Keefe M, Treister L. Victims of dating violence among high school students: Are the predictors different for males and females? Violence Against Women. 1998;4:195–223. doi: 10.1177/1077801298004002005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Leary K, Maiuro R, editors. Psychological abuse in violence domestic relations. New York, NY: Springer; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- O'Leary KD, Smith Slep AM. A dyadic longitudinal model of adolescent dating aggression. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2003;32:314–327. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3203_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Leary KD, Slep AMS, Avery-Leaf S, Cascardi M. Gender differences in dating aggression among multiethnic high school students. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;42:473–479. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer SM, Wong PTP. Multidimensional jealousy. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1989;6:181–196. doi: 10.1177/026540758900600203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. Computational tools for probing interactions in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2006;31:437–448. doi: 10.3102/10769986031004437. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush S, Bryk A, Cheong YF, Congdon R. HLM5: Hierarchical linear and nonlinear modeling. Chicago: Scientic Software International; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Reese-Weber M, Johnson AI. Examining dating violence from the relational context. In: Cunningham HR, Berry WF, editors. Handbook on the Psychology of Violence. New York: Nova Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Riggs DS, O'Leary KD. The development of a model of courtship aggression. In: Pirog-Good MA, Stets JE, editors. Violence in Dating Relationships: Emerging Social Issues. New York: Praeger; 1989. pp. 53–71. [Google Scholar]

- Riggs DS, O’Leary KD. Aggression between heterosexual dating partners an examination of a causal model of courtship aggression. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1996;11:519–540. [Google Scholar]

- Shorey RC, Cornelius TL, Bell KM. A critical review of theoretical frameworks for dating violence: Comparing the dating and marital fields. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2008;13:185–194. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2008.03.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA. Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: The conflict tactics (CT) scales. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1979:75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Vagi KJ, Rothman EF, Latzman NE, Tharp AT, Hall DM, Breiding MJ. Beyond correlates: A review of risk and protective factors for adolescent dating violence perpetration. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2013;42:633–649. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-9907-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker DJ, Haileyesus T, Swahn M, Saltzman LS. Differences in frequency of violence and reported injury between relationships with reciprocal and nonreciprocal intimate partner violence. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:941–947. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.079020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams TS, Connolly J, Pepler D, Craig W, Laporte L. Risk models of dating aggression across different adolescent relationships: A developmental psychopathology approach. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:622–632. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.4.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]