Abstract

Differentiation of hematopoietic stem-progenitor cells (HSPCs) into mature blood lineages results from the translation of extracellular signals into changes in the expression levels of transcription factors controlling cell fate decisions. Multiple transcription factor families are known to be involved in hematopoiesis. While the T-box transcription factor family is known to be involved in the differentiation of multiple tissues, and expression of T-bet, a T-box family transcription factor, has been observed in HSPCs, T-box family transcription factors do not have a described role in HSPC differentiation. In the current study, we address the functional consequences of T-bet expression in mouse HSPCs. T-bet protein levels differed among HSPC subsets, with highest levels observed in megakaryo-erythroid progenitor cells (MEPs), the common precursor to megakaryocytes and erythrocytes. HSPCs from T-bet deficient mice showed a defect in megakaryocytic differentiation when cultured in the presence of thrombopoietin. In contrast, erythroid differentiation in culture in the presence of erythropoietin was not substantially altered in T-bet deficient HSPCs. Differences observed with regard to megakaryocyte number and maturity, as assessed by level of expression of CD41 and CD61, and megakaryocyte ploidy, in T-bet deficient HSPCs were not associated with altered proliferation or survival in culture. Gene expression micro-array analysis of MEPs from T-bet deficient mice showed diminished expression of multiple genes associated with the megakaryocyte lineage. These data advance our understanding of the transcriptional regulation of megakaryopoiesis by supporting a new role for T-bet in the differentiation of MEPs into megakaryocytes.

Keywords: Hematopoiesis, Megakaryocytes, Megakaryopoiesis, Transcription Factors, T-box transcription factor, TBX21, Thrombopoiesis

Introduction

The differentiation of hematopoietic stem-progenitor cells (HSPCs) into mature lineages involves developmentally regulated gene expression resulting from the coordinated expression of specific cell-fate determining transcription factors [1]. The differentiation of HSPCs into megakaryocytes is known to involve multiple essential transcription factors, including GATA-1, GATA-2, Friend of GATA-1 (FOG-1), NF-E2, mafG, mafK, FLI-1, ZBP-89, P-TEFb, RUNX-1, sp1, and sp3[2-11]. While the interactions of these factors during megakaryopoiesis is currently under investigation, a complete understanding of the transcriptional regulation of megakaryopoiesis will be facilitated by increased knowledge of which additional transcription factors are involved. The contributions of sp1 and sp3 to megakaryopoiesis were identified only recently, and it is likely that additional transcription factors that impact megakaryopoiesis remain to be identified.

T-bet is a member of the T-box family of transcription factors that has critical effects on the differentiation of T-lymphocytes during immune responses[12]. In CD8+ T-lymphocytes, T-bet promotes terminal effector differentiation at the expense of long-term persistence as self-renewing memory [13, 14]. In CD4+ T cells, T-bet directs Th1 effector cell differentiation and suppresses the differentiation of Th2 cells, in part through mutually antagonistic interactions with a member of the GATA family of transcription factors, GATA-3[15]. T-bet expression and functions have primarily been observed in lymphoid cells, however T-bet expression has also been reported in human CD34+ HSPCs[16]. Currently there is no known function for T-bet in HSPCs.

To investigate the consequences of T-bet expression in HSPCs, we analyzed T-bet expression in known HSPC subsets in mice. We observed detectable expression of T-bet in megakaryocyte-erythroid progenitor (MEP) cells. Based on this finding, we used mice lacking the gene encoding T-bet, Tbx21, to examine the effects of T-bet deficiency on megakaryocyte and erythrocyte differentiation from HSPC enriched bone marrow populations.

Methods

Mice

Mice were housed, bred, and used in experiments in accordance with Institutional Animal Care and Use Guidelines at the University of Maryland School of Medicine. C57BL/6 mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. Tbx21−/− (T-bet KO) mice were on a C57BL/6 background and have been previously described[17]. All mice used in this study were from the same colony. Tbx21−/− mice (already on a C57BL/6 background) were backcrossed into the colony for over 7 generations prior to use.

Preparation of single cell suspensions from bone marrow and magnetic lineage depletion

Tibias and femurs were harvested from euthanized mice and crushed using mortar and pestle in RPMI + 10% FBS. The resulting mixture was filtered with 40um nylon mesh and cells were resuspended in red blood cell lysis buffer. After red blood cell lysis cells were resuspended in PBS. For lineage depletion, cells were labeled with a biotin conjugated lineage marker antibody cocktail containing antibodies to CD11b, CD3e, CD45R, Ly-6G,Ter119 (eBioscience) and anti-NK1.1 (eBioscience). Biotin conjugated anti-CD41 antibody (eBioscience) was included in the depletion cocktail in the experiments indicated. After labeling with the biotin-conjugated antibody cocktail, cells were incubated with streptavidin beads and magnetically depleted (Mylitenyi Biotech). Lineage depleted bone marrow cells used in experiments were in the flow-through fraction.

Analysis of gross bone marrow morphology

Femurs were isolated from euthanized mice and embedded in paraffin. Sections cut from paraffin blocks were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and analyzed by microscopy.

Identification of HSPC subsets by flow cytometry

Lineage depleted bone marrow cells were stained with fluorochrome conjugated antibodies to cell surface molecules for 30 minutes. Cell surface molecules stained include sca, c-kit, Flt3, CD34, CD127, and CD16/32, all stained with antibodies purchased from eBiosciences. Fluorochrome conjugated lineage marker antibody cocktail and anti-NK1.1 antibody was included to identify lineage-committed cells that were not removed by magnetic depletion. HSPC subsets in this study were defined by the following patterns of surface marker expression: LT-HSC: Lin−/sca+/kit+/Flt3−/CD34−, ST-HSC: Lin−/sca+/kit+/Flt3−/CD34+, MPP: Lin−/sca+/kit+/Flt3+/CD34+ [18] CMP: Lin−/sca−/kit+/CD127−/CD16/32−/CD34+, MEP: Lin−/sca−/kit+/CD127−/CD16/32−/CD34−, GMP: Lin−/sca−/kit+/CD127−/CD16/32+/CD34+ [19], PreMegE: Lin−/sca−/kit+/CD41−/CD16/32−/Endoglin−/CD150+ [20]. Sorting of HSPC subsets was performed using a FACSAria III (BD Biosciences). For assessment of T-bet expression by flow cytometry, after cell surface staining cells were fixed, permeabilized , and stained with fluorochrome-conjugated anti-T-bet antibody (clone O4-46, BD biosciences). Samples were acquired using a LSR II (BD biosciences) flow cytometer and analysis was performed using FlowJo software (Treestar).

Counting of peripheral blood platelets and erythrocytes

Blood samples were collected from the facial vein of C57BL/6 or T-bet KO mice. The platelet and erythrocyte counting protocol was adapted from Alugupalli, et. al. [21]. Briefly, 5 μl of blood was collected directly into 45 μl citrate anticoagulant, labeled with fluorochrome conjugated anti-CD41 antibody. 5.5 μm diameter fluorescent beads were added (105 beads/ml) prior to acquisition on an Accuri C6 (BD Biosciences) flow cytometer with analysis using FlowJo (Treestar).

HSPC culture

Lineage depleted bone marrow cells were cultured at a concentration of 0.2×106/ml in RPMI supplemented with 10% FBS. Murine SCF (50 ng /ml, Cell Signaling Technology), murine TPO (10 ng/ml, R&D Systems), or murine EPO (10 ng/ml, R&D Systems) were added to media where indicated. Cytokines were supplemented every 4 days using 20% of initial concentration. For counting of cells in culture, Rainbow Fluorescent Particle microbeads (Spherotech) were added to each 1 ml of culture. Cells were stained with anti-CD41 and anti-CD61 antibodies to identify megakaryocytes, and anti-CD71 and anti-ter-119 antibodies to identify erythroid cells (all antibodies from eBioscience). Dead cells were stained with fixable viability dye (eBioscience) and eliminated from analysis. Cells were counted by flow cytometry as number of cells per 5 × 103 microbeads.

Determination of megakaryocyte ploidy

Cells were stained with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies to CD41 and CD61 prior to fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS and permeabilization with 0.2% saponin, 0.1% sodium azide, 1% FBS in PBS. Fixed, permeabilized cells were incubated with with 100 μg/ml RNaseA and then stained with 4 μg/ml propidium iodide. DNA content was determined by flow cytometry, with acquisition on an Accuri C6 (BD Biosciences) flow cytometer with analysis using FlowJo (Treestar).

Proliferation and apoptosis assays

Proliferation was measured by flow cytometry after CFSE staining of lineage depleted bone marrow cells prior to culture as previously described[22]. Measurement of cell death and apoptosis in culture was performed by harvesting cultured cells and staining with antibody to AnnexinV in Annexin V binding buffer (BD biosciences), with the inclusion of fixable viability dye (eBioscience) to label dead cells.

Retroviral transduction and constructs

Bicistronic retrovirus encoding expressing T-bet upstream of an internal ribosomal entry sequence and green fluorescent protein was prepared as described using the MigR1 vector[22, 23]. Lineage-depleted bone marrow cells were transduced ex-vivo upon initial plating in complete media (RPMI + 10% FBS) with 8ng/ml polybrene. Plate containing cells and virus was centrifuged at 2500rpm for 1 hour and cultured overnight at 37° C. The next morning the cells were washed and re-plated in fresh complete medium.

Colony forming assays

Megakaryocyte colony forming assays were performed using a MegaCult-C kit (STEMCELL Technologies). For each sample, 1.8 x 104 lineage-depleted bone marrow cells were cultured in 0.75 ml in semi-solid media on double-chamber slides. Cultures were fixed after 8 days and stained for acetylcholinesterase activity to identify megakaryocytes.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted using RNAqueous (Life technologies). Reverse transcription was performed using SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen). An ABI PRISM 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) was used for quantitative RT-PCR using presynthesized TaqMan Gene Expression Assays. Assay IDs used this study were as follows: Mm00450960_m1 (Tbx21), Mm01351985_m1 (Eomes), Mm99999915_g1 (GAPDH). Test gene values are expressed relative to that of GAPDH, with standardization of the lowest experimental value to 1.

Microarray

MEP cells were sorted from lineage-depleted bone marrow from C57BL/6 or T-bet KO mice based on surface marker criteria described in “Identification of HSPC subsets by flow cytometry” section using a FACSAria III (BD Biosciences). RNA was isolated from sorted cells using RNAqueous (Life Technologies) and hybridized to a GeneChip Mouse Gene 2.0 ST Array (Affymetrix) and scanned using a GeneChip scanner 3000 7G (Affymetrix). Three biologic replicates were used each for C57BL/6 and T-bet KO MEP cells. Microarray analysis services were purchased from Subio inc. Data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) with accession code GSE68943.

Results

T-bet is expressed in megakaryo-erythroid progenitor cells

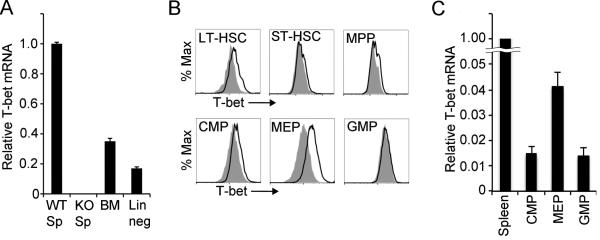

To determine whether T-bet mRNA is expressed in HSPCs, RNA was extracted from bone marrow cells of C57BL/6 mice before and after magnetic depletion of cells expressing lineage specific differentiation markers. Quantitative RT-PCR was used to quantify T-bet mRNA levels in all samples (Fig.1 A). RNA extracts from C57BL/6 splenocytes and T-bet deficient splenocytes were included as positive and negative controls, respectively. T-bet mRNA levels in whole bone marrow were about 30% of those observed in splenocytes. Since whole bone marrow includes lymphocytic populations known to express T-bet, including memory T lymphocytes and NK cells, we also examined T-bet mRNA levels in lineage-depleted bone marrow cells. After HSPC enrichment and removal of lineage-committed cell populations through lineage-depletion, T-bet mRNA levels were detected at approximately 20% of those seen in splenocytes. These results suggest that T-bet may be expressed in HSPCs, although likely at levels significantly lower than those observed in T-bet-expressing lymphocytes.

Figure 1. T-bet expression in the MEP subset of HSPCs.

(A) T-bet mRNA levels in splenocytes (Sp), whole bone marrow cells (BM), or lineage-depleted bone marrow cells (Lin neg) from C57BL/6 (WT) or T-bet KO mice (KO) as determined by quantitative real-time PCR. Values represent the mean ± SEM of triplicate determinations normalized to GAPDH expression. Results are shown relative to WT spleen, for which the mean was set to one. Results are representative of three independent experiments.

(B) T-bet protein expression in in each inicated HSPC subset, identified by cell surface marker expression as described in materials and methods, was analyzed by flow cytometry after intracellular staining for T-bet. Histograms show T-bet staining in indicated cell populations from C57BL/6 mice (solid black line) versus the same cell population from Tbet KO mice (gray, filled line). Results are representative of three independent experiments.

(C) T-bet mRNA levels in each indicated HSPC subset sorted from lineage-depleted bone marrow from C57BL/6 mice as determined by quantitative real-time PCR. Values represent the mean ± SEM of triplicate determinations normalized to GAPDH expression. Results are shown relative to WT spleen, for which the mean was set to one. Results are representative of three independent experiments.

While lineage depleted bone marrow cells are enriched for HSPCs, they are not exclusively HSPCs. HSPCs can be identified and categorized into specific subsets representing cells of differing lineage potential based on the expression of cell surface markers. To examine the expression of T-bet protein in different HSPC subsets, flow cytometry was used to analyze cell surface marker expression concurrently with intracellular staining for T-bet (Fig.1 B). Specific surface marker combinations used to identify HSPC subsets are described in the Methods section. Since non-specific antibody binding can be influenced by factors, including cell size, staining with an isotope matched non-specific control antibody is not ideal for determining whether or not a specific HSPC population expresses T-bet. Therefore, for each HSPC subset analyzed, staining with T-bet antibody was compared to staining with the same antibody in the corresponding HSPC subset from T-bet deficient lineage depleted bone marrow cells. Minimal, but reproducible, T-bet expression was detected in long-term hematopoietic stem cells and common myeloid progenitor cells, but not in short-term hematopoietic stem cells and granulocyte macrophage progenitor cells. The greatest level of expression was observed in MEP cells. To validate T-bet expression in MEP cells, CMP, GMP, and MEP cells were isolated from lineage-depleted bone marrow by cell sorting, with subsequent analysis of T-bet mRNA by quantitative RT-PCR (Fig. 1C). The results suggest stage specific expression of T-bet in HSPCs, with greatest expression in MEP cells, the HSPCs that go on to differentiate into megakaryocytes and erythrocytes.

Increased bone marrow MEP cells and normal numbers of peripheral blood platelets and erythrocytes in T-bet deficient mice

Having observed T-bet expression in MEP cells, we next sought to determine whether HSPC subset populations were altered in the bone marrow of mice lacking T-bet. Bone marrow cells from tibias and femurs of C57BL/6 mice and T-bet KO mice were isolated and analyzed by flow cytometry to count absolute numbers and percentages of known HSPC subsets. T-bet KO mice were found to have greater overall bone marrow cellularity relative to C57BL/6 (Fig. 2A). Although total bone marrow cellularity was greater in T-bet KO mice by cell count, no differences were observed in gross bone marrow morphology in paraffin sections from femurs of T-bet KO versus C57BL/6 mice (Fig. 2B). Examination of the paraffin sections reveals bone marrow cellularity in excess of 90% in both T-bet KO and C57BL/6 mice. The data show that increased bone marrow cell count observed in T-bet KO mice is unlikely to be simply due to increased cell concentration in the marrow, though it remains possible that the overall marrow compartment is larger in T-bet KO mice. The percentage of lineage-negative cells (that were not labeled with antibodies specific to lineage identifying cell surface markers) was similar in both T-bet KO and C57BL/6 bone marrow (Fig. 2C). Since the lineage negative fraction of bone marrow cells is enriched for HSPCs, the observation of greater overall cellularity and a preserved proportion of lineage negative cells in the bone marrow of T-bet KO mice suggest an increase in HSPCs.

Figure 2. T-bet deficient mice have an increased number of bone marrow MEP cells, but normal peripheral blood platelet and erythrocyte counts.

(A) Whole bone marrow cell counts from bilateral tibia and femurs of C57BL/6 (WT) or T-bet KO (KO). Graph shows mean ± SEM from 8 mice of each genotype.

(B) Hematoxylin and eosin stained paraffin sections of femurs from C57BL/6 (WT) and T-bet KO (KO) mice. Sections shown are representative of 6 paraffin sections from three different C57BL/6 mice and three different T-bet KO mice.

(C) Percentage of whole bone marrow cell count remaining after magnetic lineage-depletion in C57BL/6 (WT) or T-bet KO (KO) mice. Graph shows mean ± SEM from eight mice in each group.

(D) and (E) HSPC subets were identified by cell surface marker staining and flow cytometry as described in materials and methods. Percentage of lineage-depleted cells (D) or cell number per femurs and tibia of one mouse (E) within each HSPC subset are shown as mean ± SEM from 4 C57BL/6 (WT) or T-bet KO (KO) mice. distribution of HSPC subsets.

(F) Platelet and erythrocyte counts in peripheral blood of C57BL/6 (WT) and T-bet KO (KO) mice shown as count per 1ul blood, mean ± SEM of 7 mice of each genotype. Statistical analyses were performed by Student t test; *P<0.05, **P<0.01.

To determine the distribution of specific HSPC subset populations in bone marrow from T-bet KO mice, cell surface marker expression on lineage depleted bone marrow from T-bet KO and C57BL/6 control mice was analyzed by flow cytometry (Fig.2 D, E). Evaluating each subset as a percentage of the lineage negative bone marrow cell population, the only difference observed was in the CMP subset, with a reduction in the T-bet KO. Since greater overall bone marrow cellularity was observed in the T-bet KO, there is no defect in absolute numbers of CMP cells in T-bet KO bone marrow. Comparing total cell count of each HSPC subset between T-bet KO and C57BL/6 shows increased numbers of MEP cells in T-bet KO bone marrow.

MEP cells are the common precursor for megakaryoid and erythroid lineages, and ultimately give rise to peripheral blood platelets and erythrocytes. Having observed an increase in the absolute number of MEPs in T-bet KO bone marrow, we next measured platelet and erythrocyte counts in the peripheral blood of T-bet KO versus C57BL//6 mice by flow cytometry (Fig.2 F). No significant differences in peripheral blood platelet or erythrocyte counts were observed in T-bet KO mice relative to C57BL/6 control. These data show that T-bet deficient mice have increased MEP cells, yet maintain normal levels of the differentiated cells downstream of MEPs, platelets and erythrocytes. The results support reduced efficiency in platelet and erythrocyte differentiation from MEPs in T-bet KO mice.

Diminished megakaryocytic differentiation of T-bet deficient HSPCs in culture

Based on the observed expression of T-bet in MEP cells and increased MEP cells in the setting of normal peripheral erythrocyte and platelet counts in T-bet deficient mice, we hypothesized that T-bet has functional roles in megakaryoid and erythroid differentiation. To begin testing this hypothesis, we cultured T-bet KO versus C57BL/6 lineage depleted bone marrow cells in SCF and TPO to assess megakaryopoiesis in vitro. Anti-CD41 antibodies were added to our lineage depletion cocktail to remove HSPCs that were already committed to megakaryoid differentiation. Cells were harvested after 4, 8 and 10 days of culture and flow cytometry was used to quantify megakaryocytes and platelets in culture. The total count of live cells in the culture was not different between T-bet KO and C57BL/6, but numbers of FSChighCD41+ CD61+ megakaryocytes and FSClowCD41+CD61+ platelets were significantly reduced in T-bet KO culture (Fig. 3A, and S1). The percentage of CD41+CD61+ megakaryocytes among live cells was also significantly reduced in T-bet KO culture, with a greater reduction in more mature CD41highCD61high megakaryocytes (Fig.3 B, C, and S2).

Figure 3. Inefficient megakaryopoiesis in cultured T-bet deficient HSPCs.

(A) Lineage and CD41-depleted bone marrow cells from C57BL/6 (WT) and T-bet KO (KO) mice were cultured with SCF (50 ng/ml) and TPO (10 ng/ml) with fluorescent microbeads added to the culture. Aliquots were taken from cultures at day 4, 8, and 10 for cell count relative to microbeads of total cells and CD41+ CD61+ megakaryocytes and platelets by flow cytometry. Each point represents the mean and SEM from 9 independent cultures.

(B) FACS plots are gated on live (viability dye negative) cells from day 10 of culture under conditions described in (A). Plots are representative of 5 independent pairs of cultures.

(C) Graph shows mean and SEM of percentage of total live cells that are in the CD41+ CD61+ megakaryocyte gate (larger box with black outline in (B)) or in the CD41highCD61high mature megakaryocyte gate (smaller box with dashed outline in (B)) from 5 independent cultures of lineage and CD41 depleted bone marrow cells from C57BL6/(WT) or T-bet KO (KO) mice harvested at day 10.

(D and E) Lineage and CD41-depleted bone marrow cells from C57BL/6 (WT) or T-bet KO (KO) mice were cultured in semi-solid media with TPO (30 ng/ml) + SCF (30ng/ml) (D) TPO alone (30 ng/ml) (E). After 8 days fo culture colonies were fixed and stained for AchE activity. Plain bar graphs show mean and SEM from 3 independent cultures for each genotype of AchE positive colony counts per chamber. Stacked graphs show percentage of colonies in each of four size categories, XS: 3 to 5 cells, S: 6 to 10 cells, M: 11 to 20 cells, L: 21 cells above, for semi-solid cultures. Statistical analyses were performed by Student t test; *P<0.05, **P<0.01.

Megakaryopoiesis was also assessed by colony-forming assays in semi-solid culture. Lineage (including CD41) depleted bone marrow cells from T-bet KO and C57BL/6 control mice were cultured in serum-free semi-solid media supplemented with TPO and SCF or TPO alone. Under both cytokine conditions, significantly fewer megakaryocyte progenitor colonies were obtained when starting with lineage depleted bone marrow from T-bet KO mice (Fig. 3D, E). In addition to the reduction in the number of megakaryocyte progenitor colonies obtained, colony size was smaller in T-bet KO samples. In TPO supplemented with TPO none of the observed T-bet KO colonies was made up of more than 5 cells, and in cultures supplemented with TPO plus SCF the percentage of T-bet KO colonies that grew to over 20 cells was approximately half of that observed for C57BL/6 colonies. Overall these findings reveal a defect in megakaryocytic differentiation potential in T-bet deficient HSPCs.

Decreased megakaryocytic maturation in T-bet deficient HSPCs and increased megakaryocytic maturation on ectopic T-bet expression in HSPCs in culture

As megakaryocytes mature, they lose capacity for cell division, but increase in size and continue DNA replication, resulting in polyploidy, during endomitosis[24]. We next examined whether megakaryocytic maturation was deficient in T-bet KO HSPC cultures. Lineage (including CD41) depleted bone marrow cells from T-bet KO versus C57BL/6 control mice were cultured in the presence of SCF and TPO. Cells were harvested after 10 days in culture. Cell surface staining with anti-CD41 and anti-CD61 antibodies was used to identify megakaryocytes (Fig. S3A), and DNA was stained with propidium iodide for determination of cell ploidy. We observed diminished cell ploidy among CD41+ CD61+ megakaryocytes in T-bet KO cultures (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4. T-bet promotes increased megakaryocyte cell ploidy in culture.

(A) Lineage and CD41-depleted bone marrow cells from C57BL/6 (WT) or T-bet KO (KO) mice were cultured with SCF (50 ng/ml) and TPO (10 ng/ml) for 8 days. Histogram plot is gated on CD41+ CD61+ megakaryocytes and shows DNA content as measured by staining with propidium iodide. Plot is representative of 6 independent experiments. Peaks representing 2n or 4n cell ploidy and region representing 8n or greater ploidy are indicated. Bar graphs show percentage of cells in the CD41+ CD61+ megakaryocyte gate that have cell ploidy of 4n or lower and 8n and higher in WT and KO cultures. Values shown are mean and SEM of 6 independent experiments.

(B) Lineage and CD41-depleted bone marrow cells from C57BL/6 mice were transduced with retrovirus encoding T-bet and GFP (Mig-T-bet) versus GFP alone (Mig, vector control), and plated in SCF (50 ng/ml) and TPO (10 ng/ml) for 7 days. Histogram plot shows propidium iodine staining as a measure of DNA content in GFP+ CD41+ CD61+ transduced megakaryocyte gate. Bar graphs show percentage of GFP+ CD41+ CD61+ megakaryocytes with 4n or lower and 8n or higher cell ploidy. The histogram plot shown is representative of 4 independent experiments. Graphs show mean and SEM values of 4 independent experiments. Statistical analyses were performed by Student t test; **P<0.01.

We used a retro-viral transduction approach to determine whether over-expression of T-bet could enhance megakaryocyte ploidy in culture. Lineage (including CD41) depleted bone marrow cells from C57BL/6 mice were cultured in SCF and TPO and transduced with retrovirus to ectopically express GFP and T-bet or GFP alone. Cells were harvested after 7 days in culture. Transduced megakaryocytes were identified by expression of GFP and surface expression of CD41 (Fig. S3B), and ploidy was determined by propidium iodide staining of DNA. Ectopic expression of T-bet led to increased cell ploidy among CD41+ CD61+ megakaryocytes using cells from both C57BL/6 mice (Fig. 4B), and also from T-bet KO mice (Fig. S4). These data show that T-bet increases megakaryocyte cell ploidy in HSPC culture and support a role for T-bet in megakaryocyte maturation.

Little to no defect in megakaryocytic differentiation of purified T-bet deficient bi-potent megakaryoerythroid progenitor cells

To determine whether T-bet plays a role in the development of bi-potent megakaryo-erythroid progenitor cells, the subsequent differentiation of bi-potent cells into megakaryocytes, or both, we cultured sorted bi-potent Pre Meg E cells [20] from lineage-depleted bone marrow from C57BL/6 and T-bet KO mice (Fig. 5). While we did observe a trend towards diminished numbers of megakaryocytes in cultures from T-bet KO mice (Fig. 5A, B, C), none of these differences were of statistical significance (p>0.05, Student t test). The observed trend in liquid culture was not observed in semi-solid culture with quantitation of number and size of megakaryocyte colonies showing no difference between C57BL/6 and T-bet KO (Fig. 5D). Analysis of CD41highCD61high megakaryocyte ploidy in Pre Meg E cultures gives the appearance of a trend towards lower ploidy in the absence of T-bet that is not of statistical significance (p>0.05, Student t test) (Fig. 5E). These results suggest that T-bet influences the establishment of bi-potent megakaryo-erythroid progenitors, although a role for T-bet in subsequent megakaryocytic differentiation cannot entirely be excluded.

Figure 5. Megakaryopoiesis in cultures of sorted Pre MegE cells from T-bet deficient mice.

(A) preMegE cells were sorted from lineage-depleted bone marrow cells from C57BL/6 (WT, solid line with circles) and T-bet KO (KO) mice (dashed line with triangles) and cultured with SCF (50 ng/ml) and TPO (10 ng/ml). Cultures were harvested at day 6 for cell count relative to fluorescent microbeads of total cells and CD41+ CD61+ megakaryocytes by flow cytometry. Each point represents the mean and SEM from 3 independent cultures. No statistically significant difference between numbers of live cells or megakaryocytes was observed between WT and KO (p>0.05, Student t test).

(B) FACS plots are gated on live (viability dye negative) cells from day 6 of culture under conditions described in (A). Numbers within plots indicate percentage of cells within adjacent gate. Plots are representative of 3 independent pairs of cultures.

(C) Graph shows mean and SEM of percentage of total live cells that are in the CD41+ CD61+ megakaryocyte gate (larger gate with black outline in (B)) or in the CD41highCD61high mature megakaryocyte gate (smaller gate with dashed outline in (B)) from 3 independent cultures of preMegE from C57BL6/(WT) or T-bet KO (KO) mice harvested at day 6. No statistically significant difference between WT and KO was observed (p>0.05, Student t test).

(D) preMegE from C57BL/6 (WT) or T-bet KO (KO) mice were cultured in semi-solid media with TPO (30 ng/ml) + SCF (30ng/ml) After 6 days, culture colonies were fixed and stained for AchE activity. Plain bar graphs show mean and SEM from 3 independent cultures for each genotype of AchE positive colony counts per chamber. Stacked graphs show percentage of colonies in each of four size categories as described in Fig.3. No statistically significant difference in colony counts between WT and KO was observed (p>0.05, Student t test).

(E) preMegEs from C57BL/6 (WT) or T-bet KO (KO) mice were cultured with SCF (50 ng/ml) and TPO (10 ng/ml) for 6 days. Histogram plot is gated on CD41+ CD61+ megakaryocytes (gated as in Fig. S3A), and shows DNA content as measured by staining with propidium iodide. Histogram is representative of 3 independent experiments. Peaks representing 2n or 4n cell ploidy and region representing 8n or greater ploidy are indicated. Bar graphs show percentage of cells in the CD41+ CD61+ megakaryocyte gate with cell ploidy of 4n or lower and 8n and higher in WT and KO cultures. Values shown are mean and SEM of 3 independent experiments. No statistically significant difference between WT and KO was observed (p>0.05, Student t test).

T-bet deficiency in HSPCs leads to minimal changes in erythropoiesis

Since MEP cells give rise to both megakaryocytes and erythrocytes, we next investigated the function of T-bet in erythropoiesis. Lineage depleted bone marrow cells isolated from femurs and tibias of T-bet KO or C57BL/6 mice were cultured in the presence of SCF and EPO. Cells were harvested after 4 days of culture, and stained with fluorochrome conjugated anti-CD71 and anti-Ter119 antibodies for counting of erythroid committed cells in different stages of erythropoiesis. Four stages of erythropoiesis were defined by expression levels of CD71 and Ter119 (stage I: CD71highTer119−, stage II: CD71highTer119high, stage III: CD71midTer119high, stage IV: CD71lowTer119high)[25]. Neither the total number of live cells in culture or the number of Ter119+ erythroid committed cells in culture was altered to a statistically significant degree in T-bet KO cultures (Fig. 6A). The percentage of Ter119+ erythroid committed cells in each of the four stages of erythropoiesis was also not different in between T-bet KO and C57BL/6 cultures (Fig. 6B, C). On calculating the number of Ter119+ cells in each stage of erythropoiesis we observed a statistically significant 33% decrease in stage IV erythrocytes in T-bet KO cultures (Fig. 6C). These findings suggest that the influence of T-bet on erythropoiesis is much more modest than its role in megakaryopoiesis.

Figure 6. Modest defect in erythrocytosis in T-bet deficient HSPCs cultured in vitro.

Lineage and CD41-depleted bone marrow cells from C57BL/6 (WT) and T-bet KO (KO) mice were cultured with SCF(50ng/ml) and EPO(10ng/ml) for 4 days.

(A) Count of live cells and ter119+ erythroid cells relative to fluorescent microbeads added at plating. Graphs show mean and SEM values from 8 independent experiments.

(B) FACS plots show CD71 and ter119 staining for all live (viability dye negative) cells. Erythrocyte developmental stages I to IV are indicated on plots. Top two panels show results after 2 days of culture, and lower plots show results after four days of culture. Results shown are representative of 8 independent experiments.

(C) Quantitation of number and percentage of WT (white bars) or KO (grey bars) cells in each stage of erythroid development after 4 days of culture. Graph shows values representing mean and SEM from 8 independent experiments. Statistical analyses were performed by Student t test; *P<0.05.

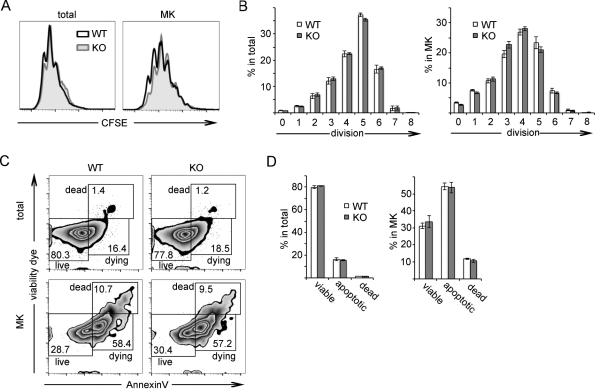

Proliferation and cell death are not altered in T-bet deficient cultured HSPCs

The diminished number of megakaryocytes observed in T-bet KO lineage-depleted bone marrow cell cultures could be secondary to increased proliferation or decreased cell death of megakaryocyte precursors. To assess whether T-bet KO HSPCs have a proliferation defect in response to SCF and TPO, we used CFSE staining to track cell division number by flow cytometry. Lineage (including CD41) depleted bone marrow from T-bet KO or C57BL/6 femurs and tibias was stained with CFSE and cultured in the presence of SCF and TPO. After 4 days of culture, a time point prior to the development of polyploid megakaryocytes, cells were harvested for analysis by flow cytometry. In both total live cell populations and CD41+ CD61+ megakaryocytes, T-bet deficiency resulted in no significant difference in proliferation as measured by number of cell divisions (Fig. 7A, B). Megakaryocytic differentiation occurs as HSPCs divide, and we observed that the megakaryocytes had more cell divisions when compared with the total live cell population.

Figure 7. T-bet deficiency does not lead to changes in proliferation or cell death in HSPCS cultured in vitro.

(A and B) Lineage and CD41-depleted bone marrow cells from C57BL/6 (WT) or T-bet KO (KO) mice were labeled with CFSE and cultured with SCF (50 ng/ml) and TPO (10 ng/ml) for 4 days. Histogram plots in (A) show WT (black, unfilled line) versus KO (gray, filled line) CFSE staining in all live cells (viability dye negative) and in CD41+ CD61+ megakaryocytes on day 4. Plots are representative of 5 independent experiments. Graphs in (B) show WT (white bars) versus KO (gray bars) percentages of total live cells or CD41+ CD61+ megakaryocytes that have undergone the indicated number of cell divisions. Values shown in graphs are mean and SEM of 5 independent experiments.

(C and D) Lineagae and CD41-depleted bone marrow cells from WT or KO mice were cultured with SCF (50 ng/ml) and TPO (10 ng/ml) for 8 days, after which cells were harvested and analyzed for cell death and apoptosis by annexin V and viability dye staining. FACS plots in (C) show dead, apoptotic, and viable cells in total cell population (top two plots) and gated CD41+ CD61+ megakaryocyte population (lower two plots). Plots are representative of 5 independent experiments. Graphs in (D) show percentages of total cells or gated CD41+ CD61+ megakaryocytes within dead, apoptotic (apo) and viable (via) box gates shown in (C). Bars shown in graphs represent mean and SEM values of 5 independent experiments

To evaluate cell death during megakaryopoiesis, lineage (including CD41) depleted bone marrow cells from T-bet KO or C57BL/6 mice were cultured in the presence of SCF and TPO and harvested after 8 days of culture. Cells were stained with antibodies directed against CD41 and CD61 to identify megakaryocytes and also stained with annexin V and a cell viability dye prior to analysis by flow cytometry. No significant differences in apoptosis or cell death were observed between T-bet KO cultures and C57BL/6 cultures in both total live cells and in megakaryocytes (Fig 7C, D). HSPCs cultured in vitro exhibit a high rate of apoptosis as they differentiate, and a greater proportion of apoptotic and dead cells was seen in the megakaryocyte populations relative to the total live cell populations. The results show that proliferation and apoptosis are not altered by T-bet deficiency in HSPCs cultured in vitro under conditions conducive to megakaryocytic differentiation.

Decreased expression of genes associated with megakaryocytic differentiation in T-bet deficient MEP cells

Following our observations of T-bet expression in MEP cells and decreased megakaryocytic differentiation in cultured HSPCs lacking T-bet, we next sought to identify differences between intact MEP cells and MEP cells lacking T-bet. Comparing global gene expression profiles of sorted MEP cells from T-bet KO and C57BL/6 mice, decreased expression of multiple genes associated with megakaryocytic differentiation was observed (Fig. 8A, B). These genes, Thpo, Itga2b, Pf4, and Mpl, along with the genes encoding the transcription factor, Hmgb2, and the receptor tyrosine kinase, Tek, were selected for validation by qRT-PCR[26-29]. Hmgb2, was assessed because it has been shown to have activity in HSPCs during erythroid differentiation[30], and Tek, because it has been shown to be involved in hematopoeisis, and specifically in thrombopoiesis[31, 32]. A complete listing of differentially expressed genes is included in Table S1 (down-regulated in T-bet KO) and Table S2 (up-regulated in T-bet KO).

Figure 8. Multiple genes associated with megakaryocytic lineage differentiation are expressed at lower levels in T-bet deficient MEP cells.

(A) Sorted MEP cell populations from lineage-depleted C57BL/6 and T-bet KO bone marrow are shown as boxed populations in FACS plots.

(B) Differentially expressed genes in T-bet KO MEP cells relative to expression in C57BL/6 MEP cells as determined by gene expression micro-array profiling of three samples from each group.

(C) qRT-PCR validation of mRNA levels of genes from (B), differentially expressed in MEP cells from C57BL/6 versus T-bet KO mice. Error bars represent SEM. Results are representative of three independent experiments.

While thrombopoietin trancripts could not be detected in either C57BL/6 or T-bet KO MEP cells by qRT-PCR, reductions in CD41 (encoded by Itga2b), Pf4, and the thrombopoietin receptor (encoded by Mpl) were observed in T-bet KO MEP cells in the validation set (Fig. 8C). Decreased expression of Tek in T-bet KO MEP cells was also validated by qRT-PCR, while increased expression of Hmgb2 was not (Fig. 8C). The results indicate that T-bet deficient MEP cells may have diminished expression of multiple genes associated with the megakaryocytic cell differentiation, suggesting a role for T-bet in the differentiation of MEP cells into megakaryocytes.

To identify find out the biological pathways affected by T-bet deficiency in MEP cells, KEGG pathway analysis was performed by uploading the list of differentially expressed genes in T-bet deficient MEP cells to DAVID, an online gene functional classification tool [33, 34]. Enriched pathways identified in our analysis are shown in Table 1. Of the pathways identified, the “hematopoietic cell lineage” and “cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction” pathways are of the most potential relevance. These two pathways are shown in Figure S5, with marking of the genes within each pathway that have altered expression in the absence of T-bet in MEP cells.

Table 1.

KEGG signaling pathways altered in T-bet deficient MEP cells.

| KEGG term | gene count |

% | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ribosome | 14 | 1.9 | 4.0E-05 |

| Primary immunodeficiency | 9 | 1.2 | 6.1E-05 |

| Hematopoietic cell lineage | 13 | 1.7 | 9.9E-05 |

| Cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction | 20 | 2.7 | 3.4E-03 |

| GnRH signaling pathway | 11 | 1.5 | 4.7E-03 |

| Leukocyte transendothelial migration | 12 | 1.6 | 7.1E-03 |

| Antigen processing and presentation | 10 | 1.3 | 9.4E-03 |

Discussion

T-box family transcription factors have critical roles in the development of several tissues[35]. While two family members, T-bet and Eomesodermin, have been studied in the context of T-lymphocytic differentiation, current knowledge of the role of T-box transcription factors in hematopoiesis is limited[12, 13, 36, 37]. In this study we provide evidence supporting a previously undescribed role for T-bet in megakaryopoiesis. The data presented move forward from previous work, showing T-bet expression in human HSPCs, by identifying the MEP cells as the HSPC subset with the highest level of T-bet expression in mice[16]. Defective megakaryopoiesis in cultured T-bet deficient HSPCs and diminished expression of factors associated with megakaryopoiesis in T-bet deficient MEP cells further support a role for T-bet in megakaryocytic differentiation.

The observed consequences of T-bet deficiency on megakaryopoiesis in vivo, an increase in bone marrow MEP cells with no peripheral platelet defect, though relatively modest, suggest an interesting compensated inefficiency in platelet generation from T-bet deficient MEP cells. Although such compensation could arise from a number of mechanisms, one possibility is the expression of a related factor, such as another T-box transcription factor, with functions that overlap those of T-bet. There are multiple examples of related transcription factors with at least partially redundant function during megakaryopoiesis, including the (Sp)/Kruppel-like, Maf, and GATA transcription factor families. While a marked defect in megakaryopoiesis is observed in mice lacking Sp1 and Sp3, no defect is seen in mice lacking only Sp1 or Sp3[3]. Similarly, mafK deficient mice showed minimal defects and mafG deficient mice are mildly thrombocytopenic, while mice lacking both mafK and mafG suffer postnatal lethality with severe defects in megakaryopoiesis and erythropoiesis[8]. The functional redundancies of GATA transcription factors in hematopoiesis are complex, and suggest partial redundancy between GATA-1, GATA-2, and GATA-3, with a greater requirement for GATA-1 for megakaryopoiesis[38-41]. Little is known of the expression patterns of T-box transcription factors other than T-bet during hematopoiesis.

The identification of a role for T-bet in megakaryopoiesis, along with the established roles of GATA family transcription factors and evidence supporting the importance transcription factor interactions raise the question of whether T-bet interacts with GATA transcription factors during megakaryocytic differentiation. In T-lymphocytes there is a well-studied, mutually antagonistic interaction between T-bet and GATA-3 that guides T-lymphocyte fate decisions during immune responses[42]. T-bet has been shown to directly interact with GATA-3 and influence GATA-3 gene regulatory element binding activity[43]. The binding of T-bet to GATA-3 is dependent on tyrosine phosphorylation of T-bet. Potential interactions between T-bet and GATA-1 or GATA-2, and whether T-bet is tyrosine phosphorylated during megakaryopoiesis are promising areas for future investigation.

HSPC proliferation and apoptosis in culture with TPO was not changed by T-bet deficiency, providing evidence that the diminished numbers of megakaryocytes in cultures of HSPCs lacking T-bet are due to a function for T-bet in megakaryocyte lineage commitment rather than increased survival or proliferation of megakaryocytic precursors. A function for T-bet in megakaryocyte lineage commitment is also consistent with the finding of T-bet expression in MEP cells, thought to be the final non-committed progenitor cell stage in megakaryocyte and erythroid lineages[41]. As MEP cells differentiate into megakaryocytes, they lose the capacity for self-renewal and progress towards a state of terminal differentiation. In activated CD8+ T cells, T-bet promotes terminal differentiation of effector cells, while expression of fellow T-box family transcription factor, Eomesodermin, promotes preservation as self-renewing memory[13, 36]. A role in the differentiation of MEP cells into terminally differentiated megakaryocytes would be reminiscent of T-bet’s role in the differentiation of CD8+ T cells into terminally differentiated effectors during immune responses.

The differentiation of HSPCs into megakaryocytes is governed by the coordinated expression of, and interaction between, a network of transcription factors that is incompletely understood. The data presented provide evidence that T-bet is a member of this network that promotes megakaryopoiesis by supporting the differentiation of MEP cells into megakaryocytes. Our findings provide a rationale for further study of T-box family transcription factors in hematopoiesis.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

T-bet is expressed in megakaryo-erythroid progenitor (MEP) cells.

Megakaryopoiesis is defective in cultured T-bet deficient hematopoietic progenitor cells.

T-bet promotes megakaryocytic lineage commitment of MEP cells and enhances megakaryocyte maturation.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Institute of Health grants (P30CA134274, K08HL93207), and the Marlene and Stewart Greenebaum Cancer Center. We thank Ferenc Livak for assistance with flow cytometry and cell sorting.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Gottgens B. Regulatory network control of blood stem cells. Blood. 2015;125:2614–2620. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-08-570226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Huang H, Yu M, Akie TE, et al. Differentiation-dependent interactions between RUNX-1 and FLI-1 during megakaryocyte development. Molecular and cellular biology. 2009;29:4103–4115. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00090-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Meinders M, Kulu DI, van de Werken HJ, et al. Sp1/Sp3 transcription factors regulate hallmarks of megakaryocyte maturation and platelet formation and function. Blood. 2015;125:1957–1967. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-08-593343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Stachura DL, Chou ST, Weiss MJ. Early block to erythromegakaryocytic development conferred by loss of transcription factor GATA-1. Blood. 2006;107:87–97. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Shivdasani RA, Fujiwara Y, McDevitt MA, Orkin SH. A lineage-selective knockout establishes the critical role of transcription factor GATA-1 in megakaryocyte growth and platelet development. The EMBO journal. 1997;16:3965–3973. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.13.3965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Chang AN, Cantor AB, Fujiwara Y, et al. GATA-factor dependence of the multitype zinc-finger protein FOG-1 for its essential role in megakaryopoiesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99:9237–9242. doi: 10.1073/pnas.142302099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Shivdasani RA, Rosenblatt MF, Zucker-Franklin D, et al. Transcription factor NF-E2 is required for platelet formation independent of the actions of thrombopoietin/MGDF in megakaryocyte development. Cell. 1995;81:695–704. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90531-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Onodera K, Shavit JA, Motohashi H, Yamamoto M, Engel JD. Perinatal synthetic lethality and hematopoietic defects in compound mafG::mafK mutant mice. The EMBO journal. 2000;19:1335–1345. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.6.1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Hart A, Melet F, Grossfeld P, et al. Fli-1 is required for murine vascular and megakaryocytic development and is hemizygously deleted in patients with thrombocytopenia. Immunity. 2000;13:167–177. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Woo AJ, Moran TB, Schindler YL, et al. Identification of ZBP-89 as a novel GATA-1-associated transcription factor involved in megakaryocytic and erythroid development. Molecular and cellular biology. 2008;28:2675–2689. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01945-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Elagib KE, Rubinstein JD, Delehanty LL, et al. Calpain 2 activation of P-TEFb drives megakaryocyte morphogenesis and is disrupted by leukemogenic GATA1 mutation. Developmental cell. 2013;27:607–620. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Lazarevic V, Glimcher LH, Lord GM. T-bet: a bridge between innate and adaptive immunity. Nature reviews Immunology. 2013;13:777–789. doi: 10.1038/nri3536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Intlekofer AM, Takemoto N, Kao C, et al. Requirement for T-bet in the aberrant differentiation of unhelped memory CD8+ T cells. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2007;204:2015–2021. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Joshi NS, Cui W, Chandele A, et al. Inflammation directs memory precursor and short-lived effector CD8(+) T cell fates via the graded expression of T-bet transcription factor. Immunity. 2007;27:281–295. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Jenner RG, Townsend MJ, Jackson I, et al. The transcription factors T-bet and GATA-3 control alternative pathways of T-cell differentiation through a shared set of target genes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:17876–17881. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909357106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Faedo A, Ficara F, Ghiani M, Aiuti A, Rubenstein JL, Bulfone A. Developmental expression of the T-box transcription factor T-bet/Tbx21 during mouse embryogenesis. Mechanisms of development. 2002;116:157–160. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00114-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Song C, Sadashivaiah K, Furusawa A, Davila E, Tamada K, Banerjee A. Eomesodermin is required for antitumor immunity mediated by 4-1BB-agonist immunotherapy. Oncoimmunology. 2014;3:e27680. doi: 10.4161/onci.27680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Chao MP, Seita J, Weissman IL. Establishment of a normal hematopoietic and leukemia stem cell hierarchy. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2008;73:439–449. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2008.73.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Mayle A, Luo M, Jeong M, Goodell MA. Flow cytometry analysis of murine hematopoietic stem cells. Cytometry Part A : the journal of the International Society for Analytical Cytology. 2013;83:27–37. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.22093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Pronk CJ, Rossi DJ, Mansson R, et al. Elucidation of the phenotypic, functional, and molecular topography of a myeloerythroid progenitor cell hierarchy. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:428–442. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Alugupalli KR, Michelson AD, Barnard MR, Leong JM. Serial determinations of platelet counts in mice by flow cytometry. Thrombosis and haemostasis. 2001;86:668–671. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Banerjee A, Schambach F, DeJong CS, Hammond SM, Reiner SL. Micro-RNA-155 inhibits IFN-gamma signaling in CD4+ T cells. European journal of immunology. 2010;40:225–231. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Pear WS, Miller JP, Xu L, et al. Efficient and rapid induction of a chronic myelogenous leukemia-like myeloproliferative disease in mice receiving P210 bcr/abl-transduced bone marrow. Blood. 1998;92:3780–3792. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Machlus KR, Italiano JE., Jr. The incredible journey: From megakaryocyte development to platelet formation. The Journal of cell biology. 2013;201:785–796. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201304054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Zhang J, Socolovsky M, Gross AW, Lodish HF. Role of Ras signaling in erythroid differentiation of mouse fetal liver cells: functional analysis by a flow cytometry-based novel culture system. Blood. 2003;102:3938–3946. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].de Sauvage FJ, Carver-Moore K, Luoh SM, et al. Physiological regulation of early and late stages of megakaryocytopoiesis by thrombopoietin. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1996;183:651–656. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.2.651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Drachman JG, Kaushansky K. Dissecting the thrombopoietin receptor: functional elements of the Mpl cytoplasmic domain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94:2350–2355. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Dumon S, Walton DS, Volpe G, et al. Itga2b regulation at the onset of definitive hematopoiesis and commitment to differentiation. PloS one. 2012;7:e43300. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Lambert MP, Rauova L, Bailey M, Sola-Visner MC, Kowalska MA, Poncz M. Platelet factor 4 is a negative autocrine in vivo regulator of megakaryopoiesis: clinical and therapeutic implications. Blood. 2007;110:1153–1160. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-067116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Laurent B, Randrianarison-Huetz V, Marechal V, Mayeux P, Dusanter-Fourt I, Dumenil D. High-mobility group protein HMGB2 regulates human erythroid differentiation through trans-activation of GFI1B transcription. Blood. 2010;115:687–695. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-06-230094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Li X, Slayton WB. Molecular mechanisms of platelet and stem cell rebound after 5-fluorouracil treatment. Experimental hematology. 2013;41:635–645. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2013.03.003. e633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Puri MC, Bernstein A. Requirement for the TIE family of receptor tyrosine kinases in adult but not fetal hematopoiesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100:12753–12758. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2133552100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Bioinformatics enrichment tools: paths toward the comprehensive functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:1–13. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Papaioannou VE. The T-box gene family: emerging roles in development, stem cells and cancer. Development. 2014;141:3819–3833. doi: 10.1242/dev.104471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Banerjee A, Gordon SM, Intlekofer AM, et al. Cutting edge: The transcription factor eomesodermin enables CD8+ T cells to compete for the memory cell niche. Journal of immunology. 2010;185:4988–4992. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Intlekofer AM, Banerjee A, Takemoto N, et al. Anomalous type 17 response to viral infection by CD8+ T cells lacking T-bet and eomesodermin. Science. 2008;321:408–411. doi: 10.1126/science.1159806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Ferreira R, Wai A, Shimizu R, et al. Dynamic regulation of Gata factor levels is more important than their identity. Blood. 2007;109:5481–5490. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-11-060491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Goldfarb AN. Megakaryocytic programming by a transcriptional regulatory loop: A circle connecting RUNX1, GATA-1, and P-TEFb. Journal of cellular biochemistry. 2009;107:377–382. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Bresnick EH, Lee HY, Fujiwara T, Johnson KD, Keles S. GATA switches as developmental drivers. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2010;285:31087–31093. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R110.159079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Dore LC, Crispino JD. Transcription factor networks in erythroid cell and megakaryocyte development. Blood. 2011;118:231–239. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-285981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Evans CM, Jenner RG. Transcription factor interplay in T helper cell differentiation. Briefings in functional genomics. 2013;12:499–511. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/elt025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Hwang ES, Szabo SJ, Schwartzberg PL, Glimcher LH. T helper cell fate specified by kinase-mediated interaction of T-bet with GATA-3. Science. 2005;307:430–433. doi: 10.1126/science.1103336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.