Abstract

A 65-year-old man presents with a rash of 2 days duration over the right forehead with vesicles and pustules, a few lesions on the right side and tip of the nose, and slight blurring in the right eye. The rash was preceded by tingling in the area and is now associated with aching pain. How should this patient be evaluated and treated?

THE CLINICAL PROBLEM

Primary infection with varicella-zoster virus (VZV) results in chickenpox, manifested by viremia with a diffuse rash and seeding of multiple sensory ganglia where the virus establishes life-long latency. Herpes zoster is caused by reactivation of latent VZV from cranial nerve or dorsal root ganglia with spread of virus along the sensory nerve to the dermatome. There are more than 1 million cases of herpes zoster in the United States each year with an annual rate of 3 to 4 cases per 1000 persons. Studies suggest that the incidence of herpes zoster is increasing.1 Unvaccinated persons who live to age 85 have a 50% chance of developing herpes zoster. Up to 3% of patients with zoster require hospitalization.

The major risk factor for herpes zoster is increasing age. With increasing time after varicella, there is a reduction in the level of T cell immunity to VZV2 which, unlike virus-specific antibodies, correlates with protection from zoster. The risk is higher in women than men, in whites than blacks, and in persons with a family history of herpes zoster.3 Chickenpox that occurs in utero or early in infancy, at a time when the cellular immune system is not fully matured, is associated with herpes zoster in childhood. Immunocompromised persons with impaired T cell immunity, including organ and hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients, persons receiving immunosuppressive therapy, and patients with lymphoma, leukemia, or HIV infection, are at increased risk of developing herpes zoster and having more severe disease.

Postherpetic neuralgia (PHN), or pain persisting after the rash has resolved (often defined specifically as pain persisting 90 days or more after onset of rash), is a feared complication of herpes zoster. The pain may persist for many months or even years; it may be severe and interfere with sleep and activities of daily living, resulting in anorexia, weight loss, fatigue, depression, withdrawal from social activities and employment, and loss of independent living. Depending on age and the definition used, ten to 50% of persons with herpes zoster develop PHN. The risk increases with increasing age (particularly over age 50) and is greater in persons with severe pain at the onset of herpes zoster or severe rash with a large number of lesions.

Various neurologic complications have been reported to occur with herpes zoster including Bell’s palsy, the Ramsay-Hunt syndrome, transverse myelitis, transient ischemic attacks, or stroke.4 In addition, ophthalmologic complications of zoster occurring in the V1 distribution of the trigeminal nerve can include keratitis, scleritis, uveitis, or acute retinal necrosis (Table 1). Immunocompromised persons can develop additional complications including disseminated skin disease, verrucous skin lesions, acute or progressive outer retinal necrosis, chronic zoster, or infection with acyclovir-resistant VZV. In these patients the disease can involve multiple organs (e.g. lung, gastrointestinal tract, brain) and patients may present with hepatitis or pancreatitis several days before the rash appears.5

Table 1.

Selected Complications of Herpes Zoster in the Non-Immunocompromised Host

| Complication | Manifestations | Site of VZV reactivation |

|---|---|---|

| Aseptic meningitis | Headache, meningismus | Cranial nerve V |

| Bacterial superinfection | Streptococcus, staphylococcus cellulitis | Any sensory ganglia |

| Bell’s palsy | Unilateral facial paralysis | Cranial nerve VII |

| Eye involvement (herpes zoster ophthalmicus) | Keratitis, episcleritis, iritis, conjunctivitis, uveitis, acute retinal necrosis, optic neuritis, acute glaucoma. | Cranial nerve II, III, or V (ophthalmic [V1] branch) |

| Hearing impairment | Deafness | Cranial nerve VIII |

| Motor neuropathy | Weakness, diaphragm paralysis, neurogenic bladder | Any sensory ganglia |

| Postherpetic neuralgia | Pain persisting for 90 days after onset of rash | Any sensory ganglia |

| Ramsay-Hunt syndrome | Ear pain and vesicles in the canal, numbness of anterior tongue, facial paralysis | Cranial nerve VII geniculate ganglia and spread to cranial nerve VIII |

| Transverse myelitis | Paraparesis, sensory loss, sphincter impairment | Vertebral ganglia |

| Vasculopathy (encephalitis) | Vasculitis of cerebral arteries, confusion, seizures, TIAs, stroke | Cranial nerve V |

STRATEGIES AND EVIDENCE

EVALUATION

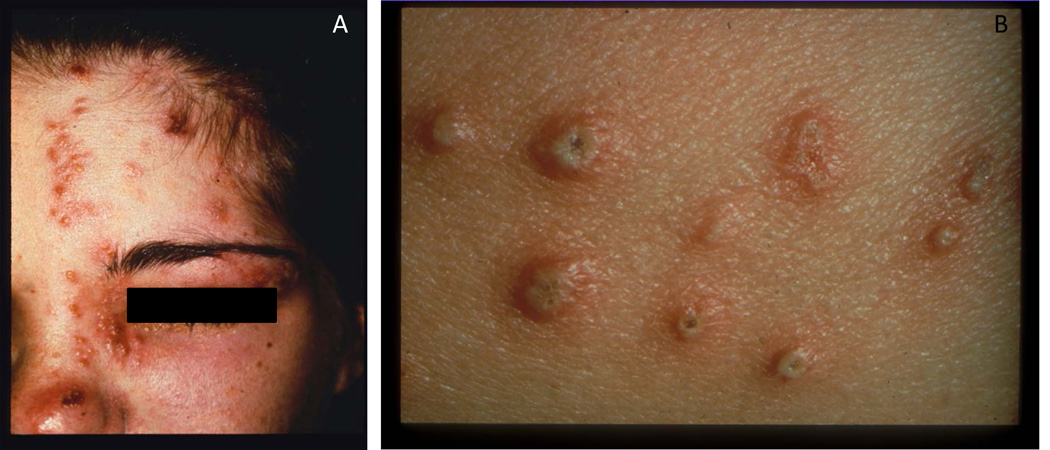

The rash of herpes zoster is dermatomal and does not cross the midline, consistent with reactivation from dorsal root or cranial nerve ganglia. The thoracic, trigeminal (Fig. 1A), lumbar, and cervical dermatomes are the most frequent sites of rash, although any area of the skin can be involved. In non-immunocompromised persons, a few scattered lesions outside the affected dermatome are not unexpected. The rash is often preceded by tingling, itching, and/or pain for 2 to 3 days, which can be continuous or episodic. Depending upon the location and severity, this prodromal pain may lead to misdiagnosis and costly testing. The rash begins as macules and papules which evolve into vesicles and then pustules (Fig. 1B). New lesions appear over 3 to 5 days, often with filling in of the dermatome despite antiviral treatment. The rash usually dries with crusting in 7 to 10 days. Some persons have pain in the absence of a rash, termed zoster sine herpete, which is difficult to diagnose and may lead to numerous unnecessary tests or procedures. Immunocompromised patients may have disseminated rashes with viremia and new lesions occurring for up to 2 weeks. The characteristics of pain associated with herpes zoster may vary. Patient may have paresthesias (e.g. burning or tingling), dysethesias (altered or painful sensitivity to touch), allodynia (pain associated with non-painful stimuli) or hyperesthesia (exaggerated or prolonged response to pain). Pruritis is also commonly associated with herpes zoster.

Figure 1.

(A) Zoster in the ophthalmic (V1) branch of the trigeminal ganglia. Photograph courtesy of Michael Oxman, M.D. (B) Vesicles and pustules in a patient with zoster. These are representative photographs and are not from the case presented.

DIAGNOSIS

Most cases of herpes zoster can be diagnosed clinically, although direct immunofluorescence for VZV antigen or PCR for VZV DNA in cells from the base of lesions after they are unroofed may be needed for atypical rashes. In a study comparing PCR with other diagnostic methods, the sensitivity and specificity of PCR was 95% and 100% respectively, and, using immunofluorescent VZV antigen testing, was 82% and 76%, respectively.6 The most common condition mistaken for zoster is herpes simplex virus, which can recur in a dermatomal distribution; accordingly, when patients present with “recurrent zoster,” atypical lesions, or are immunocompromised with disseminated skin lesions, specific testing for both VZV and herpes simplex virus is often useful. VZV has been demonstrated in saliva of persons with zoster, although such testing does not currently have a demonstrated role in clinical practice.7

PCR of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) has been used for diagnosis of CNS vasculopathy; demonstration of an increase in the ratio of anti-VZV antibody in CSF to that in the blood is more sensitive.4 PCR of the blood may be helpful for diagnosis of visceral zoster in immunocompromised persons who present with hepatitis or pancreatitis without a rash.5 PCR of blood or CSF for VZV has been used for diagnosis of zoster sine herpete.

TREATMENT AND PREVENTION

Antiviral Therapy

Antiviral therapy is recommended for herpes zoster for certain non-immunocompromised patients and all immunocompromised patients (Table 2). Other persons might also benefit from antiviral therapy, although their risk of complications from zoster is lower. Three guanosine analogs- acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir- have been licensed by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of herpes zoster (Table 3). Oral bioavailability and levels of antiviral drug activity in the blood are higher and more reliable in those receiving thrice daily valacyclovir or famciclovir than for acyclovir 5 times daily. This is important, because VZV is less sensitive than herpes simplex virus to acyclovir, valacyclovir, or famciclovir. These antivirals hasten resolution of lesions, reduce new lesion formation, reduce virus shedding, and decrease severity of acute pain (Table 3). For example, in the largest randomized, double-blind trial of acyclovir for zoster, oral acyclovir given within 47 hours of onset shortened the mean time for the last day of new lesion formation, loss of vesicles, and full crusting by 0.5 days, 1.8 days, and 2.2 days, respectively, compared with placebo.10 In another large trial, acyclovir reduced duration of virus shedding by 0.8 days compared with placebo.11 In a meta-analysis of several randomized, controlled trials, antivirals did not significantly reduce the incidence of PHN19 and they are not approved for prevention of PHN by the FDA. Valacyclovir or famciclovir have been shown to be superior to acyclovir for reducing pain associated with herpes zoster in some studies.14,15 Valacyclovir is comparable to famciclovir in terms of efficacy for reducing acute pain and accelerating healing.20 As compared with acyclovir, valacyclovir and famciclovir require fewer daily doses, but are more expensive. While controlled trials have initiated treatment within 72 hours of onset of the rash, and treatment is recommended to start within this interval and as early as possible, many experts recommend that if new skin lesions are still appearing or complications of herpes zoster are present, treatment should be initiated even if the rash began more than 3 days prior. Treatment is usually given for 7 days in the absence of complications of herpes zoster. Intravenous acyclovir is recommended for immunocompromised persons who require hospitalization or for persons with severe neurologic complications. Foscarnet is used for immunocompromised patients with acyclovir-resistant VZV.

Table 2.

Indications for Antiviral Treatment for Patients with Herpes Zostera

| ≥50 years old |

| Moderate or severe pain |

| Severe rash |

| Involvement of the face or eye |

| Other complications of zoster |

| Immunocompromised persons |

Table 3.

Antiviral Therapy for Herpes Zoster*

| Medication | Dose | Effects Observed in Controlled Trials |

Side Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nonimmunocompromised persons | |||

| Acyclovir (oral) | 800 mg po 5 times daily for 7–10 days | Reduced time to last new lesion formation, loss of vesicles, full crusting, cessation of viral shedding; reduced severity of acute pain10–12 | malaise |

| Famiclovir (oral) | 500 mg po 3 times daily × 7 days | Reduced time to last new lesion formation, loss of vesicles, full crusting, cessation of viral shedding, cessation of pain13,14 | headache, nausea |

| Valacyclovir (oral) | 1 gm po 3 times daily × 7 days | Reduced time to last new lesion formation, loss of vesicles, full crusting, cessation of pain15,16 | headache, nausea |

| Immunocompromised persons requiring hospitalization or severe neurologic complications | |||

| Acyclovir (intravenous) | 10 mg/kg iv every 8 hrs × 7–10 days | Reduced time to last new lesion formation, full crusting, cessation of virus shedding, cessation of pain; reduced cutaneous dissemination, reduced visceral zoser17,18 | renal insufficiency |

| Foscarnet+ (for acyclovir-resistant VZV) | 40 mg/kg every 8 hr until healed | not reported | renal insufficiency, hypokalemia, hypocalcemia, hypomagnesemia, hypophosphatemia, nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, anemia, granulocytopenia, headache |

All drugsin this table are available as generics

Not approved for this use by FDA

Corticosteroids

The use of corticosteroids with antiviral therapy for uncomplicated herpes zoster remains controversial. Randomized controlled trials have demonstrated benefits of a tapering course of predisone21 or prednisolone12, including reducing acute pain,12,21 improving performance of activities of daily living,21 accelerated early healing,12 and time to complete healing in one21 but not another study.12 The addition of corticosteroids to antiviral therapy has not been shown to reduce the incidence of PHN. Owing to their immunosuppressive properties, corticosteroids should not be administered for herpes zoster without concomitant antiviral therapy. Corticosteroids should generally be avoided in patients with hypertension, diabetes mellitus, peptic ulcer disease, or osteoporosis; particular caution is warranted in elderly patients, who are at increased risk of serious adverse events with treatment. Prednisone is used for treatment of certain CNS complications of herpes zoster such as vasculopathy or Bell’s palsy in non-immunocompromised patients.

Acute pain associated with herpes zoster

Several medications have been used for the treatment of acute pain associated with herpes zoster (Table 4). Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or acetaminophen can be tried for patients with mild pain. Opioids, such as oxycodone, are used for more severe pain associated with herpes zoster. Opioids were more effective than gabapentin for herpes zoster pain in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial.22 Gabapentin was shown in one,23 but not another22 controlled trial to reduce pain associated with herpes zoster. Lidocaine patches reduced pain associated with herpes zoster in a placebo-controlled trial, and should only be applied to intact skin, not to the area of the rash.24 While tricyclic antidepressants have not been shown to be effective in randomized controlled clinical trials for acute zoster pain, they have been used when opioids are insufficient for pain.

Table 4.

Medications commonly used for treatment of acute pain associated with herpes zoster*

| Medication | Dose | Titration | Maximum Dose |

Side Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analgesics-opioid and non-opioid | ||||

| Oxycodone | 5 mg every 4 hrs as needed | Increase by 5 mg 4 times daily every 2 days as tolerated | None specified, but do not exceed 120 mg daily without pain specialist | Drowsiness, dizziness, constipation, nausea, vomiting |

| Tramadol | 50 mg once or twice daily | Increase by 50–100 mg daily in divided doses every 2 days as tolerated | 400 mg daily; 300 mg dailyif >75 years old | Drowsiness, dizziness, constipation, nausea, vomiting |

| Corticosteroids^ | ||||

| Prednisone | 60 mg daily for 7 days, then decrease to 30 mg daily for 7 days, then decrease to 15 mg daily for 7 days | None | 60 mg | Gastrointestinal distress, nausea, vomiting, mood changes, edema, glucose intolerance, increased blood pressure |

| Anticonvulsants | ||||

| Gabapentin | 300 mg at bedtime or 100–300 mg 3 times daily | Increase by 100–300 mg 3 times daily every 2 days as tolerated | 3600 mg daily | Drowsiness, dizziness, ataxia, peripheral edema |

| Pregabalin | 75 mg at bedtime or 75 mg twice daily | Increase by 75 mg twice daily every 3 days as tolerated | 600 mg daily | Drowsiness, dizziness, ataxia, peripheral edema |

| Tricyclic antidepressants | ||||

| Nortriptyline | 25 mg at bedtime | Increase by 25 mg daily every 2–3 days as tolerated | 150 mg daily | Drowsiness, dry mouth, blurred vision, weight gain, urinary retention |

| Topical therapy | ||||

| Lidocaine 5% patch | One patch topically for up to 12 hours to intact skin only | None | One patch for up to 12 hours within a 24-hour period | Local irritation; if systemic absorption can cause drowsiness, dizziness |

Modified from Dworkin RH, Johnson RW, Breuer J, et al. Recommendations for the management of herpes zoster. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44 Suppl 1:S1–26, by permission of Oxford University Press.

This list provides examples and is not meant to be comprehensive

The use of corticosteroids is controversial as they are often poorly tolerated in older patients.

Eye disease associated with zoster

Patients with zoster in the V1 distribution of the trigeminal nerve (including lesions on the forehead and the upper eyelid) and either the tip of the nose or new visual symptoms should be evaluated by an ophthalmologist. Other treatment may be needed in addition to antiviral therapy, including mydriatics to dilate the pupil and reduce the risk of scarring (synechiae), topical corticosteroids for keratitis, episcleritis, or iritis, medications to reduce ocular pressure for glaucoma, or intravitreal antiviral therapy for immunocompromised patients with retinal necrosis.

Postherpetic neuralgia

Pain associated with PHN is often challenging to treat. Detailed discussion of PHN management is beyond the scope of this article. In brief, medications demonstrated in randomized trials to reduce pain associated with PHN include topical lidocaine25, anticonvulsants (e.g. gabapentin26 or pregabalin27), opioids,28 tricyclic antidepressants (e.g. nortriptyline29), and capsaicin30. Combined modalities, such as gabapentin and nortriptyline31 or an opiate and gabapentin32 have been more effective for PHN than single agent therapy, but also confer greater risk of side effects. Even with treatment, many patients do not have adequate relief of pain and referral to a pain specialist can be helpful.

Prevention of Herpes Zoster

A live attenuated zoster vaccine is recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices in persons age 60 and older to prevent herpes zoster and its complications, including PHN.9,33, Based on the results of a recent clinical trial, the vaccine is now approved by the FDA for use in persons age 50 or above to prevent herpes zoster.34 The efficacy of the vaccine to prevent herpes zoster is 70% in persons aged 50 to 59, 64% in persons aged 60 to 69, and 38% in persons 70 or above.33–35 Vaccine efficacy for prevention of PHN is 66% in persons aged 60 to 69 and 67% in persons 70 or older.33,35 A follow-up study showed that the reduction in the risk of herpes zoster remained significant for at least 5 years after vacation, though vaccine effectiveness declined over time.36 Among vaccinated (as compared with unvaccinated) persons who develop herpes zoster, pain was significantly shorter in duration and less severe.33 The vaccine can be given to persons with a prior history of herpes zoster; in a recent report, rates of adverse events associated with vaccination were similar between those who had prior zoster (mean 3.6 years prior to vaccination) and those with no history of zoster.37

The optimal timing of vaccination after an episode of zoster is uncertain. Since the risk of recurrent zoster after a recent episode of the disease is relatively low,38 and the cellular immune response to VZV is similar during the first 3 years after receiving the zoster vaccine and after having an episode of zoster,39 one might delay vaccination in immunocompetent persons with a recent history of zoster providing that it is well documented by a health care provider. The vaccine is contraindicated in persons with hematologic malignancies whose disease is not in remission or have received cytotoxic chemotherapy within 3 months, in persons with T cellular immunodeficiency (e.g. HIV infection with CD4 count ≤200/mm3 or <15% of total lymphocytes), and in those receiving high dose immunosuppressive therapy (e.g. ≥20 mg of prednisone daily for ≥2 weeks or anti-TNF therapy).

Infection Control

While herpes zoster is less contagious than varicella, patients with zoster can transmit VZV to susceptible persons and cause varicella. Non-immunocompromised persons with dermatomal zoster should be placed on contact precautions and lesions should be covered if possible;40 however, virus transmission has occasionally been reported in such patients.41 Persons with disseminated lesions or immunocompromised persons with herpes zoster should be placed on airborne and contact precautions until all lesions have crusted.

AREAS OF UNCERTAINTY

Improved therapies are needed for pain associated with herpes zoster and PHN and to prevent development of PHN after herpes zoster. Studies are needed to determine which patients are at highest risk for PHN so that more aggressive therapy can be given. There is uncertainty regarding the effectiveness of the zoster vaccine in persons ≥80 years old, the safety and effectiveness of the vaccine in persons with immunocompromising conditions that are currently considered contraindications to vaccination, the duration of immunity induced by the vaccine, and whether booster doses will be needed.

GUIDELINES

Recommendations have been published for the management of herpes zoster from a group of experts8 and for prevention of herpes zoster by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.9 The present review is generally concordant with these recommendations.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Whereas herpes zoster is often mild in healthy young persons, older individuals are at increased risk of pain and complications including PHN, ocular disease, motor neuropathy, or CNS disease. In the vast majority of cases, the diagnosis can be made clinically. Antiviral therapy is most beneficial for persons with complications of zoster or at increased risks of complications such as older persons and immunocompromised persons, and should be initiated as soon as possible, and generally within 72 hours of the onset of rash. Valacyclovir or famciclovir are preferred over acyclovir due to reduced frequency of dosing and higher levels of antiviral drug activity. The patient described above should receive oral antiviral therapy, medication for pain (e.g. opioid, with addition of gabapentin if needed), and prompt referral to an ophthalmologist. He should also be advised to avoid contact with persons who have not had varicella or have not received the varicella vaccine until his lesions have completely crusted. I would recommend herpes zoster vaccination in the future to reduce his risk of recurrence, but would tend to defer this in an immunocompetant patient for approximately 3 years, given that a zoster episode is expected to boost his cellular immune response to VZV.

Take Home Points.

In the absence of zoster vaccine, persons who live to age 85 have a 50% chance of developing herpes zoster.

Persons most likely to benefit from antiviral therapy for herpes zoster include those with complications of zoster, and those at risk for complications including immunocompromised persons, those ≥ 50 years old, and those with severe pain or severe rash.

Antivirals hasten resolution of herpes zoster lesions and decrease severity of acute pain, but have not been convincingly been shown to reduce the risk of postherpetic neuralgia.

Valacyclovir or famciclovir are preferred to acyclovir due to ease of dosing and higher levels of antiviral drug activity.

Patients with zoster and new visual symptoms should be evaluated by an ophthalmologist to determine whether ocular-specific therapy is needed.

The zoster vaccine is approved by the FDA for persons ≥50 years old and is used in persons with and without a history of zoster.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. I thank Drs. Adriana Marques and Michael Oxman for reviewing the manuscript.

Footnotes

The views expressed here are those of the author and not necessarily those of US government.

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported. Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

References

- 1.Rimland D, Moanna A. Increasing incidence of herpes zoster among Veterans. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:1000–1005. doi: 10.1086/651078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hayward AR, Herberger M. Lymphocyte responses to varicella zoster virus in the elderly. J Clin Immunol. 1987;7:174–178. doi: 10.1007/BF00916011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hicks LD, Cook-Norris RH, Mendoza N, Madkan V, Arora A, Tyring SK. Family history as a risk factor for herpes zoster: a case-control study. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:603–608. doi: 10.1001/archderm.144.5.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilden D, Cohrs RJ, Mahalingam R, Nagel MA. Varicella zoster virus vasculopathies: diverse clinical manifestations, laboratory features, pathogenesis, and treatment. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:731–740. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70134-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Jong MD, Weel JF, van Oers MH, Boom R, Wertheim-van Dillen PM. Molecular diagnosis of visceral herpes zoster. Lancet. 2001;357:2101–2102. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)05199-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sauerbrei A, Eichhorn U, Schacke M, Wutzler PJ. Laboratory diagnosis of herpes zoster. Clin Virol. 1999;14:31–36. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6532(99)00042-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mehta SK, Tyring SK, Gilden DH, et al. Varicella-zoster virus in the saliva of patients with herpes zoster. J Infect Dis. 2008;197:654–657. doi: 10.1086/527420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dworkin RH, Johnson RW, Breuer J, et al. Recommendations for the management of herpes zoster. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(Suppl 1):S1–S26. doi: 10.1086/510206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harpaz R, Ortega-Sanchez IR, Seward JF Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Prevention of herpes zoster: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) MMWR Recomm Rep. 2008;57(RR-5):1–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McKendrick MW, McGill JI, White JE, Wood MJ. Oral acyclovir in acute herpes zoster. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1986;293:1529–1532. doi: 10.1136/bmj.293.6561.1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huff JC, Bean B, Balfour HH, Jr, et al. Therapy of herpes zoster with oral acyclovir. Am J Med. 1988;85(2A):84–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wood MJ, Johnson RW, McKendrick MW, Taylor J, Mandal BK, Crooks J. A randomized trial of acyclovir for 7 days or 21 days with and without prednisolone for treatment of acute herpes zoster. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:896–900. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199403313301304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tyring S, Barbarash RA, Nahlik JE, et al. Famciclovir for the treatment of acute herpes zoster: effects on acute disease and postherpetic neuralgia. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Collaborative Famciclovir Herpes Zoster Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:89–96. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-123-2-199507150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Degreef H Famciclovir Herpes Zoster Clinical Study Group. Famciclovir, a new oral antiherpes drug: results of the first controlled clinical study demonstrating its efficacy and safety in the treatment of uncomplicated herpes zoster in immunocompetent patients. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 1994;4:241–246. doi: 10.1016/0924-8579(94)90024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beutner KR, Friedman DJ, Forszpaniak C, Andersen PL, Wood MJ. Valaciclovir compared with acyclovir for improved therapy for herpes zoster in immunocompetent adults. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1546–1553. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.7.1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin WR, Lin HH, Lee SS, et al. Comparative study of the efficacy and safety of valaciclovir versus acyclovir in the treatment of herpes zoster. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2001;34:138–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balfour HH, Jr, Bean B, Laskin OL, et al. Acyclovir halts progression of herpes zoster in immunocompromised patients. N Engl J Med. 1983;308:1448–1453. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198306163082404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shepp DH, Dandliker PS, Meyers JD. Treatment of varicella-zoster virus infection in severely immunocompromised patients. A randomized comparison of acyclovir and vidarabine. N Engl J Med. 1986;314:208–212. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198601233140404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li Q, Chen N, Yang J, et al. Antiviral treatment for preventing postherpetic neuralgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009:CD006866. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006866.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tyring SK, Beutner KR, Tucker BA, Anderson WC, Crooks RJ. Antiviral therapy for herpes zoster: randomized, controlled clinical trial of valacyclovir and famciclovir therapy in immunocompetent patients 50 years and older. Arch Fam. Med. 2000;9:863–869. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.9.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whitley RJ, Weiss H, Gnann JW, Jr, et al. Acyclovir with and without prednisone for the treatment of herpes zoster. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Collaborative Antiviral Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:376–383. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-5-199609010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dworkin RH, Barbano RL, Tyring SK, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of oxycodone and of gabapentin for acute pain in herpes zoster. Pain. 2009;142:209–217. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berry JD, Petersen KL. A single dose of gabapentin reduces acute pain and allodynia in patients with herpes zoster. Neurology. 2005;65:444–447. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000168259.94991.8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin PL, Fan SZ, Huang CH, et al. Analgesic effect of lidocaine patch 5% in the treatment of acute herpes zoster: a double-blind and vehicle-controlled study. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2008;33:320–325. doi: 10.1016/j.rapm.2007.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Galer BS, Rowbotham MC, Perander J, Friedman E. Topical lidocaine patch relieves postherpetic neuralgia more effectively than a vehicle topical patch: results of an enriched enrollment study. Pain. 1999;80:533–538. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00244-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rice AS, Maton S Postherpetic Neuralgia Study Group. Gabapentin in postherpetic neuralgia: a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled study. Pain. 2001;94:215–224. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00407-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stacey BR, Barrett JA, Whalen E, Phillips KF, Rowbotham MC. Pregabalin for postherpetic neuralgia: placebo-controlled trial of fixed and flexible dosing regimens on allodynia and time to onset of pain relief. J Pain. 2008;9:1006–1017. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Watson CP, Babul N. Efficacy of oxycodone in neuropathic pain: a randomized trial in postherpetic neuralgia. Neurology. 1998;50:1837–1841. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.6.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raja SN, Haythornthwaite JA, Pappagallo M, et al. Opioids versus antidepressants in postherpetic neuralgia: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Neurology. 2002;59:1015–1021. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.7.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Irving GA, Backonja MM, Dunteman E, et al. A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, controlled study of NGX-4010, a high-concentration capsaicin patch, for the treatment of postherpetic neuralgia. Pain Med. 2011;12:99–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2010.01004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gilron I, Bailey JM, Tu D, Holden RR, Jackson AC, Houlden RL. Nortriptyline and gabapentin, alone and in combination for neuropathic pain: a double-blind, randomised controlled crossover trial. Lancet. 2009;374:1252–1261. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61081-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gilron I, Bailey JM, Tu D, Holden RR, Weaver DF, Houlden RL. Morphine, gabapentin, or their combination for neuropathic pain. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1324–1334. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oxman MN, Levin MJ, Johnson GR, et al. A vaccine to prevent herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia in older adults. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2271–2284. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmader KE, Levin MJ, Gnann JW, Jr, et al. Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of herpes zoster vaccine in persons aged 50–59 years. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:922–928. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oxman MN, Levin MJ Shingles Prevention Study Group. Vaccination against Herpes Zoster and Postherpetic Neuralgia. J Infect Dis. 2008;197(Suppl 2):S228–S236. doi: 10.1086/522159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schmader KE, Oxman MN, Levin MJ, et al. Persistence of the efficacy of zoster vaccine in the shingles prevention study and the short-term persistence substudy. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:1320–1328. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morrison VA, Oxman MN, Levin MJ, et al. Safety of Zoster Vaccine in Elderly Adults Following Documented Herpes Zoster. J Infect Dis. 2013 Apr 30; doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit182. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tseng HF, Chi M, Smith N, Marcy SM, Sy LS, Jacobsen SJ. Herpes zoster vaccine and the incidence of recurrent herpes zoster in an immunocompetent elderly population. J Infect Dis. 2012;206:190–196. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weinberg A, Zhang JH, Oxman MN, et al. Varicella-zoster virus-specific immune responses to herpes zoster in elderly participants in a trial of a clinically effective zoster vaccine. J Infect Dis. 2009;200:1068–1077. doi: 10.1086/605611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Siegel JD, Rhinehart E, Jackson M, Chiarello L Health Care Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. 2007 Guideline for Isolation Precautions: Preventing Transmission of Infectious Agents in Health Care Settings. Am J Infect Control. 2007;35(10 Suppl 2):S65–S164. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lopez AS, Burnett-Hartman A, Nambiar R, et al. Transmission of a newly characterized strain of varicella-zoster virus from a patient with herpes zoster in a long-term-care facility, West Virginia, 2004. J Infect Dis. 2008;197:646–653. doi: 10.1086/527419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]